Exploring the Relationship Between Electronic Device Use and Psychological Dimensions of Procrastination in University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- RQ1: What are the predominant screen usage habits among university students?

- -

- RQ2: How is screen use related to the dimensions of procrastination?

- -

- RQ3: Is it possible to predict students’ perceived level of procrastination by knowing the dimensions associated with procrastination?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Method

2.2. Sample

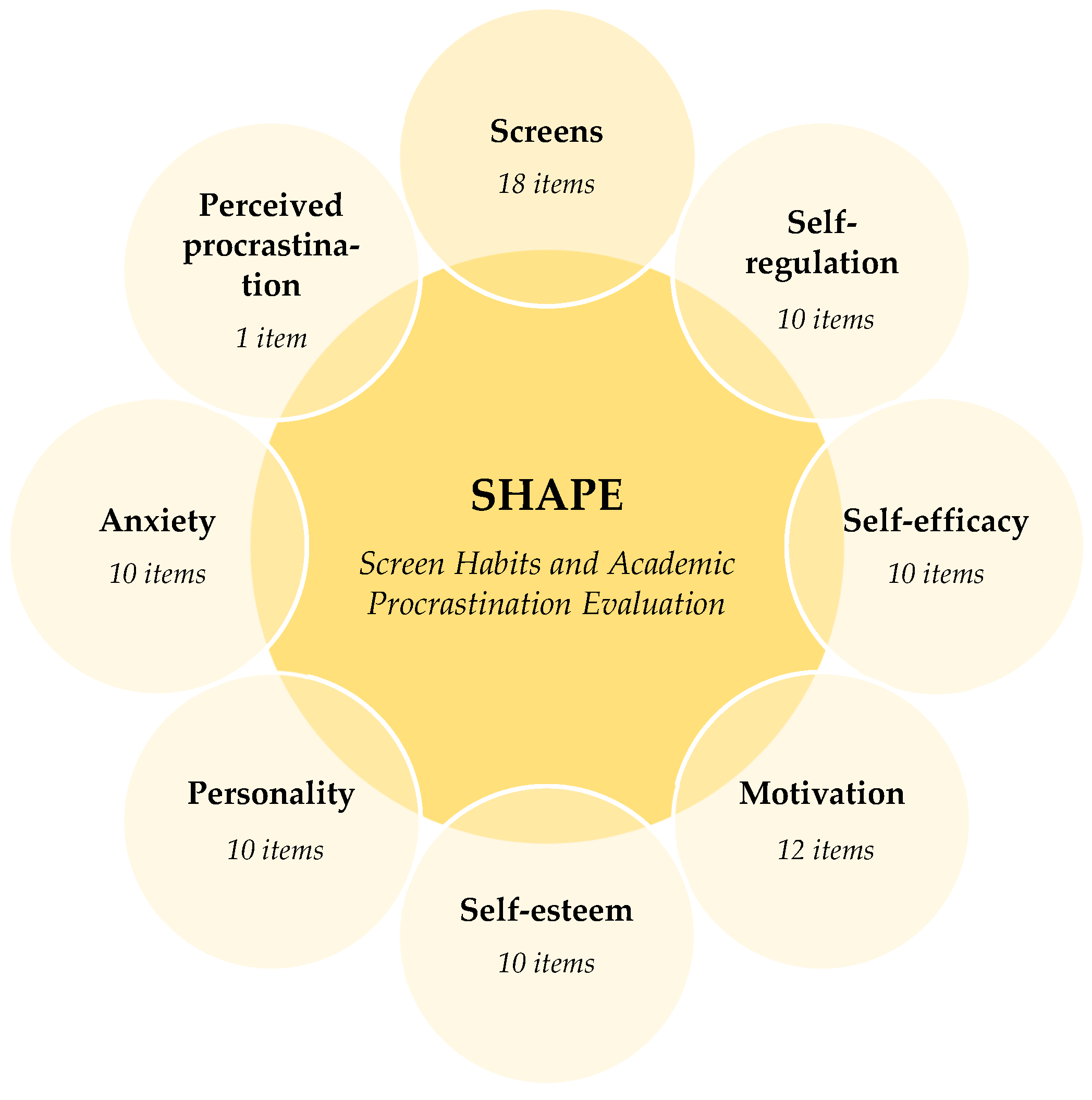

2.3. Instrument

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sample

3.2. Internal Structure of the Instrument

3.3. Screen Usage Habits of Students

3.4. Psychological Dimensions of Procrastination

3.5. Relationship Between Screen Use and Academic Procrastination According to Its Dimensions

3.6. Predictive Ability of Study Variables on Perceived Procrastination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adelakun, N. O., Olajide, M. B., & Adebisi, M. A. S. K. L. (2023). The significance of social media in shaping students’ academic performance: Challenges, benefits, and quality assurance outlook. Information Matters, 3(8), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, J. H., & Mahmood, N. (2013). Development and validation of an academic self-regulation scale for university students. Journal of Behavioural Sciences, 23(2), 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Tapia, J., Panadero Calderón, E., & Díaz Ruiz, M. A. (2014). Development and validity of the emotion and motivation self-regulation questionnaire (EMSR-Q). The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 17, E55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzabidi, T., Sahari, N. M., & Saleh, R. R. (2024). Academic performance and academic self-efficacy among pre-university students in Malaysia. IIUM Journal of Educational Studies, 12(1), 4–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarnath, A., Ozmen, S., Struijs, S. Y., de Wit, L., & Cuijpers, P. (2023). Effectiveness of a guided internet-based intervention for procrastination among university students—A randomized controlled trial study protocol. Internet Interventions, 32, 100612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggoro, A. (2021). The relationship between academic procrastination and stress level of medical students. Scientia Psychiatrica, 4(2), 369–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awopetu, R. G., Olabimitan, B. A., Kolawole, S. O., Newton, R. T., Odok, A. A., & Awopetu, A. V. (2024). The systematic review of social media addiction and mental health of Nigerian university students: The good, the bad and the ugly. European Journal of Theoretical and Applied Sciences, 2(1), 767–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar Díaz, I., Kopecký, K., Romero Rodríguez, J. M., Cáceres Reche, M. P., & Trujillo Torres, J. M. (2020). Patologías asociadas al uso problemático de internet. Una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis en WOS y Scopus. Investigación Bibliotecológica: Archivonomía, Bibliotecología e Información, 34(82), 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzaakiyyah, H. K. (2023). The impact of social media use on social interaction in contemporary society. Technology and Society Perspectives (TACIT), 1(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, P., Chandra, K., Vanishree, M., & Amritha, N. (2019). Relationship between academic procrastination and self-esteem among dental students in Bengaluru City. Journal of Indian Association of Public Health Dentistry, 17(2), 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, J. B., Dal Cin, S., Campbell, S. W., & Panek, E. (2016). Consciousness and self-regulation in mobile communication. Human Communication Research, 42(1), 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bela, A., Thohiroh, S., Efendi, Y. R., & Rahman, S. (2023). Prokrastinasi akademik dan manajemen waktu terhadap stres akademik pada mahasiswa di masa pandemi: Review literatur. Jurnal Psikologi Wijaya Putra (Psikowipa), 4(1), 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, J. (2021). Measuring perceived control: Exploratory factor analysis of a perceived control scale among United States job seekers. Authorea Preprints. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailovskaia, J., Cosci, F., Mansueto, G., & Margraf, J. (2021). The relationship between social media use, stress symptoms and burden caused by coronavirus (COVID-19) in Germany and Italy: A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro Bolaños, S., & Mahamud Rodríguez, K. (2017). Procrastinación académica y adicción a internet en estudiantes universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Avances En Psicología, 25(2), 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-C., Yang, T.-A., & Lee, J.-C. (2021). The relationship between smartphone addiction, parent–child relationship, loneliness and self-efficacy among senior high school students in Taiwan. Sustainability, 13(16), 9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R. N. C., & Miranda, J. O. (2024). Examining procrastination using the DSM-5 personality trait model: Disinhibition as a core personality trait. Current Psychology, 43(7), 6243–6252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardara, E., & Al-Makhalid, K. A. (2022). Procrastination, negative emotional symptoms, and mental well-being among college students in Saudi Arabia. Anales de Psicología, 38(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M., Pandit, U., Nerurkar, A., Verma, C., & Gandhi, S. (2021). Test anxiety and procrastination in physiotherapy students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 10(1), 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo, K., Valenzuela, R., Pestana, J. V., & Codina, N. (2024). Self-regulation and procrastination in college students: A tale of motivation, strategy, and perseverance. Psychology in the Schools, 61(3), 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahati, M., Kahkjam, M., & Sadat Naghibi, F. (2014). P11: Relationship between anxiety and personality types of female students. The Neuroscience Journal of Shefaye Khatam, 2(3), 35. [Google Scholar]

- Favieri, F., Forte, G., Savastano, M., & Casagrande, M. (2024). Validation of the brief screening of social network addiction risk. Acta Psychologica, 247, 104323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, J. R., Johnson, J. L., & McCown, W. G. (1995). Procrastination and task avoidance: Theory, research, and treatment. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Furnham, A., & Cheng, H. (2024). The Big-Five personality factors, cognitive ability, health, and social-demographic indicators as independent predictors of self-efficacy: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 65(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M., Teng, Z., Wei, Z., Jin, K., Xiao, J., Tang, H., Wu, H., Yang, Y., Yan, H., Chen, J., Wu, R., Zhao, J., Wu, Y., & Huang, J. (2022). Internet addiction among teenagers in a Chinese population: Prevalence, risk factors, and its relationship with obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 153, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J., Han, L., Gao, F., Jou, M., & Huang, C.-C. (2018). Internet addiction and procrastination among Chinese young adults: A moderated mediation model. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasempour, S., Babaei, A., Nouri, S., Basirinezhad, M. H., & Abbasi, A. (2024). Relationship between academic procrastination, self-esteem, and moral intelligence among medical sciences students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. G. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günlü, A., & Ceyhan, A. A. (2017). Investigating adolescents’ behaviors on the internet and problematic internet usage. Addicta: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 4(1), 75–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanah, S. I., Tafrilyanto, C. F., & Aini, Y. (2019). Mathematical Reasoning: The characteristics of students’ mathematical abilities in problem solving. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1188, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A. A., Kojuri, J., & Mitra Amini, M. D. (2020). Academic procrastination of medical students: The role of internet addiction. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 8(2), 83. [Google Scholar]

- Hen, M., & Goroshit, M. (2020). The effects of decisional and academic procrastination on students’ feelings toward academic procrastination. Current Psychology, 39(2), 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herawati, I., Makhmudah, U., & Suryawati, C. T. (2023). Hubungan antara self-regulated learning dengan kecemasan akademik pada peserta didik. Jurnal Psikoedukasi Dan Konseling, 7(1), 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y. (2024). Relationship between personality traits and learning burnout among undergraduates: Mediating effect of general procrastination. International Journal of Arts and Social Science, 7(3), 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y. M., Li, C. M., & Ruan, M. E. (2024). Relationship between academic self-efficacy and academic burnout among college students: Mediating effect of general procrastination. Global Journal of Arts Humanities and Social Sciences, 4(2), 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, S. C., Houghton, S., Zadow, C., Rosenberg, M., Wood, L., Shilton, T., & Lawrence, D. (2017). Development of the adolescent preoccupation with screens scale. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihkamuddin, M., Ichsan, N. A., & Ni’matuzahroh. (2024). Perfectionism as causes of academic procrastination at collage?: A sytematic review. International Journal of Scientific Research and Management (IJSRM), 12(7), 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalamazh, R., Voloshyna-Narozhna, V., Tymoshchuk, Y., & Balashov, E. (2024). Coping styles and self-regulation abilities as predictors of anxiety. Insight: The Psychological Dimensions of Society, 12, 96–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, M. A., & Watson, J. C. (2017). Examining associations among achievement motivation, locus of control, academic stress, and life satisfaction: A comparison of U.S. and international undergraduate students. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S., Kumari, B., Thakur, R., & Muthukumaran, T. (2022). Personality style and its relation with level of anxiety. International Journal of Nursing Education, 14(4), 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, M. (2024). The influence of MBTI personality types on college students’ academic performance: The mediating role of learning motivation. Journal of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences, 29, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemal, F., Riniati, W. O., Haetami, A., Wahab, A., & Pratiwi, E. Y. R. (2023). The analysis of relationship between learning motivation and student procrastination behavior in public elementary school. Journal on Education, 5(3), 7710–7714. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, C. S. R. (2024). Self-esteem, coping strategies, and anxiety among generation Z: A correlational study. Global Research Journal of Social Sciences and Management, 2(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzhan, A., Shaikym, A., & Sadyk, U. (2023, June 1–2). A comparative study of the impact of electronic devices on university students’ academic performance. 2023 17th International Conference on Electronics Computer and Computation (ICECCO) (pp. 1–4), Almaty, Kazakhstan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Y., & Hancock, J. T. (2024). Social media mindsets: A new approach to understanding social media use and psychological well-being. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 29(1), zmad048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Ran, G., Zhang, Q., & Hu, T. (2019). A meta-analysis of self-efficacy and mental health in the context of China. Psychological Development and Education, 35, 759–769. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B., Teo, E. W., & Yan, T. (2022). The impact of smartphone addiction on Chinese university students’ physical activity: Exploring the role of motivation and self-efficacy. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 2273–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. J., & Jin, C. C. (2018). Relationship between mobile phone dependence and learning burnout among college students: Moderating effect of personality. Chinese Journal of Special Education, 5, 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lonka, K., Chow, A., Keskinen, J., Hakkarainen, K., Sandström, N., & Pyhältö, K. (2014). How to measure PhD students’ conceptions of academic writing—And are they related to well-being? Journal of Writing Research, 5(3), 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, A. A., & Paiva, M. O. A. (2024). Self-regulation in academic success: Exploring the impact of volitional control strategies, time management planning, and procrastination. International Journal of Changes in Education, 1(3), 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, C., & Chóliz, M. (2013). Tratamiento cognitivo-Conductual en un caso de adicción a Internet y videojuegos. [Cognitive-behavioral treatment in a case of internet and videogames addiction]. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 13(1), 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, A. (2022). Studying problems, not problematic usage: Do mobile checking habits increase procrastination and decrease well-being? Mobile Media & Communication, 10(2), 272–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesfin, A., & Gebremeskel, M. M. (2023). The practice of time management by Debre Markos college of teacher education students: Multitasking, procrastination, task prioritization, and technology use. Bahir Dar Journal of Education, 23(3), 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreta-Herrera, R., Durán Rodríguez, T., & Villegas Villacrés, N. (2018). Regulación Emocional y Rendimiento como predictores de la Procrastinación Académica en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Psicología y Educación—Journal of Psychology and Education, 13(2), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousset, E. S.-P., Lane, J., Therriault, D., & Roberge, P. (2024). Association between self-efficacy and anxiety symptoms in adolescents: Secondary analysis of a preventive program. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 3, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrawin, F. J. (2023). The predictability of self-esteem on the motivation towards learning among students in the upper basic elementary grades in the Latin patriarchate schools in Jordan. Jordanian Educational Journal, 8(3), 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez-Guzmán, R., & Cisneros-Chavez, B. (2019). Adicción a redes sociales y procrastinación académica en estudiantes universitarios. Nuevas Ideas En Informática Educativa, 15, 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ņikadimovs, O., & Vēvere, V. (2024). The use of generative artificial intelligence in higher education: University social responsibility and stakeholders’ perceptions. Environment. Technologies. Resources. Proceedings of the International Scientific and Practical Conference, 2, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, E., Morin, A. J. S., Tardif-Grenier, K., Archambault, I., Dupéré, V., & Hébert, C. (2022). Profiles of anxious and depressive symptoms among adolescent boys and girls: Associations with coping strategies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(3), 570–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parwez, S., Khurshid, S., & Yousaf, I. (2023). Impact of procrastination on self-esteem of college and university students of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Multicultural Education, 9(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascoe, M. C., Hetrick, S. E., & Parker, A. G. (2020). The impact of stress on students in secondary school and higher education. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L. d. C., & Ramos, F. P. (2021). Procrastinação acadêmica em estudantes universitários: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 25, e223504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnomo, R. A. A., Susanto, A. R. A., & Oktavianisa, N. A. (2024). The role of self efficacy on academic procrastination among university student. Jurnal Psikologi Teori Dan Terapan, 15(1), 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, A. S. A., Diaz, R. Y. R., Quispe, W. V., Garcia, M. H., & Ramirez, M. C. (2020). La procrastinación académica: Teorías, elementos y modelos. Revista Muro de la investigación, 5(2), 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Gazki, P., Ilaghi, M., & Masoumian, N. (2024). The triangle of anxiety, perfectionism, and academic procrastination: Exploring the correlates in medical and dental students. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, G. J., & Moreno, O. (2019). Ansiedad y autoestima: Su relación con el uso de redes sociales en adolescentes Mexicanos. Revista Electrónica de Psicología Iztacala, 22(1), 367–381. [Google Scholar]

- Roick, J., & Ringeisen, T. (2017). Self-efficacy, test anxiety, and academic success: A longitudinal validation. International Journal of Educational Research, 83, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Journal of Religion and Health. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowbotham, M., & Schmitz, G. S. (2013). Development and validation of a student self-efficacy scale. Journal of Nursing & Care, 2(1), 1000126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozgonjuk, D., Kattago, M., & Täht, K. (2018). Social media use in lectures mediates the relationship between procrastination and problematic smartphone use. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabrina, R., Risnawati, R., Anwar, K., Hulawa, D. E., Sabti, F., Rijan, M. H. B. M., & Kakoh, N. A. (2023). The relation between self-regulation, self-efficacy and achievement motivation among muslim students in senior high schools. International Journal of Islamic Studies Higher Education, 2(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero-Pazos, M. R., & Reyes-de-Cózar, S. (2023). Interventions to reduce academic procrastination: A systematic review. International Journal of Educational Research, 121, 102228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saplavska, J., & Jerkunkova, A. (2018, May 23–25). Academic procrastination and anxiety among students. 17th International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development, Jelgava, Latvia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, O. E., Mills, J. S., & Samson, L. (2024). Out of the loop: Taking a one-week break from social media leads to better self-esteem and body image among young women. Body Image, 49, 101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C. D. (1970). Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory (self-evaluation questionnaire). Consulting Psychologists Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P., & Klingsieck, K. B. (2016). Academic procrastination: Psychological antecedents revisited. Australian Psychologist, 51(1), 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subiyakto, D. M., Saktini, F., & Sumekar, T. A. (2024). The relationship between social media addiction and self-esteem in medical students of Diponegoro University. Jurnal Kedokteran Diponegoro (Diponegoro Medical Journal), 13(4), 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujarwoto, Saputri, R. A. M., & Yumarni, T. (2023). Social media addiction and mental health among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(1), 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska-Gieracha, J., & Mazurek, J. (2020). The role of self-efficacy in the recovery process of stroke survivors. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 13, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantalean Terrones, L. J., Del Rosario Pacherres, O., Aguirre Morales, M. T., Livia Segovia, J. H., & Franco Mendoza, J. M. (2024). Estrés, ansiedad y depresión como factores asociados a la procrastinación académica en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. Comuni@cción, 15(3), 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J., & Deane, F. P. (2002). Development of a short form of the test anxiety inventory (TAI). The Journal of General Psychology, 129(2), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tisocco, F., & Liporace, M. F. (2023). Structural relationships between procrastination, academic motivation, and academic achievement within university students: A self-determination theory approach. Innovative Higher Education, 48(2), 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türel, Y. K., & Dokumaci, O. (2022). Use of media and technology, academic procrastination, and academic achievement in adolescence. Participatory Educational Research, 9(2), 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usán Supervía, P., Salavera Bordás, C., Juarros Basterretxea, J., & Latorre Cosculluela, C. (2023). Influence of psychological variables in adolescence: The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between self-efficacy and satisfaction with life in senior high school students. Social Sciences, 12(6), 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedian-Azimi, A., & Moayed, M. S. (2021). The relationship between self-esteem and academic motivation among postgraduate nursing students: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 15(2), 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Valente, S., Dominguez-Lara, S., & Lourenço, A. (2024). Planning time management in school activities and relation to procrastination: A study for educational sustainability. Sustainability, 16(16), 6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R. J., Pelletier, L. G., Blais, M. R., Briere, N. M., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. F. (1992). The academic motivation scale: A measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Abeele, M. M. P. (2021). Digital wellbeing as a dynamic construct. Communication Theory, 31(4), 932–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Eijnden, R. J. J. M., Lemmens, J. S., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2016). The social media disorder scale. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Liu, Y., Wang, Z., & Wang, T. (2023). The influences of the Big Five personality traits on academic achievements: Chain mediating effect based on major identity and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1065554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Kou, Z., Du, Y., Wang, K., & Xu, Y. (2022). Academic procrastination and negative emotions among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: The mediating and buffering effects of online-shopping addiction. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 789505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weurlander, M., Wänström, L., Seeberger, A., Lönn, A., Barman, L., Hult, H., Thornberg, R., & Wernerson, A. (2024). Development and validation of the physician self-efficacy to manage emotional challenges scale (PSMEC). BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Liu, R.-D., Ding, Y., Hong, W., & Jiang, S. (2023). The relations between academic procrastination and self-esteem in adolescents: A longitudinal study. Current Psychology, 42(9), 7534–7548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurdakoş, K., & Biçer, E. B. (2019). The effect of internet addiction level on academic procrastination: A research on health management students. YYU Journal of Education Faculty, 16(1), 243–278. [Google Scholar]

| Sample | RQ | Study |

|---|---|---|

| Sample 1: 924 | RQ3 | Predictive regression models |

| Subsample or Sample 2: 386 | RQ1 RQ2 | Screen-use patterns and their association with procrastination |

| Dimensions | Scales | Cronbach’s Alpha | Authors (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screens | Adolescent Preoccupation with screens scale (APSS) | Emotional = 0.91 Behavioural = 0.87 | Hunter et al. (2017) |

| Social Media Disorder Scale (9-item SMD scale) | 0.76 | van den Eijnden et al. (2016) | |

| Self-regulation | (ASRS) Academic Self-Regulation Scale | 0.83 | Akhtar and Mahmood (2013) |

| (EMSR-Q) Emotion and motivation Self-Regulation Questionnaire | Avoidance = 0.69 Performance = 0.72 Negative = 0.79 Positive = 0.70 Process = 0.70 | Alonso-Tapia et al. (2014) | |

| Self-efficacy | Student Self-Efficacy (SSE) | 0.84 | Rowbotham and Schmitz (2013) |

| Motivation | Academic Motivation Scale-College (AMS-C) | 0.81 | Vallerand et al. (1992) |

| Self-esteem | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | 0.84 | Rosenberg (1965) |

| Personality | (IPIP) International Personality Item Pool | Extroversion = 0.87 Agreeableness = 0.82 Conscientiousness = 0.79 Neuroticism = 0.86 Openness to Experience = 0.84 | Goldberg et al. (2006) |

| Anxiety | TAI-5 item: Test Anxiety Inventory | 0.87 | Taylor and Deane (2002) |

| (STAI-T) The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | Trait = 0.90 State = 0.94 | Spielberger (1970) |

| Scale | No. Item | α-Cronbach |

|---|---|---|

| Screen Use | 18 | 0.892 |

| Self-Regulation | 10 | 0.614 |

| Self-Efficacy | 10 | 0.892 |

| Motivation | 12 | 0.848 |

| Self-Esteem | 10 | 0.899 |

| Personality | 10 | 0.651 |

| Anxiety | 10 | 0.883 |

| Total (N = 386) | 80 | 0.852 |

| Dimensions | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Regulation | 386 | 1.90 | 4.8 | 3.286 | 0.48162 |

| Self-Efficacy | 386 | 1.00 | 5.0 | 4.0106 | 0.63509 |

| Motivation | 386 | 1.91 | 5.0 | 4.1003 | 0.65138 |

| Self-Esteem | 386 | 1.60 | 5.0 | 3.6549 | 0.76866 |

| Anxiety | 386 | 1.00 | 5.0 | 3.2826 | 0.8572 |

| Personality | 386 | 1.00 | 4.9 | 3.6466 | 0.51427 |

| Self-Efficacy | Personality | Anxiety | Self-Regulation | Motivation | Self-Esteem | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCREENS | Pearson correlation | −0.205 ** | 0.095 | 0.375 ** | −0.276 ** | 0.02 | −0.313 ** |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0 | 0.063 | 0 | 0 | 0.698 | 0 | |

| SELF_EFFICACY | Pearson correlation | 1 | 0.204 ** | −0.291 ** | 0.334 ** | 0.422 ** | 0.528 ** |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| PERSONALITY | Pearson correlation | 1 | 0.336 ** | 0.246 ** | 0.343 ** | 0.022 | |

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.667 | |||

| ANXIETY | Pearson correlation | 1 | −0.134 ** | 0.084 | −0.555 ** | ||

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0.008 | 0.101 | 0 | ||||

| SELF-REGULATION | Pearson correlation | 1 | 0.429 ** | 0.328 ** | |||

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0 | 0 | |||||

| MOTIVATION | Pearson correlation | 1 | 0.204 ** | ||||

| Sig. (bilateral) | 0 | ||||||

| Model | R | R Square | R Square Corrected | Standard Error of Estimation | Durbin- Watson |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.564 | 0.318 | 0.310 | 0.67899 | 2.048 |

| Model | Sum of Squares | gf | Quadratic Mean | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regression | 195.927 | 11 | 17.812 | 38.634 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 420.463 | 912 | 0.461 | |||

| Total | 616.390 | 923 | ||||

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Typified Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 2.744 | 0.342 | 8.021 | 0.000 | |

| Screens_TimeUse | 0.302 | 0.039 | 0.277 | 7.790 | 0.000 |

| Screens_Emotions | −0.037 | 0.045 | −0.030 | −0.828 | 0.408 |

| Screens_Problems | −0.012 | 0.040 | −0.010 | −0.293 | 0.770 |

| SelfRegulation_Positive | −0.484 | 0.038 | −0.432 | −12.704 | 0.000 |

| SelfRegulation_Negative | 0.149 | 0.043 | 0.115 | 3.495 | 0.000 |

| SelfRegulation_Class Attendance | 0.013 | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.406 | 0.685 |

| Self_Efficacy | 0.151 | 0.045 | 0.112 | 3.341 | 0.001 |

| Motivation | 0.015 | 0.055 | 0.008 | 0.271 | 0.786 |

| Self_Esteem | 0.044 | 0.074 | 0.018 | 0.603 | 0.547 |

| Personality | 0.050 | 0.054 | 0.029 | 0.927 | 0.354 |

| Anxiety | −0.016 | 0.034 | −0.016 | −0.454 | 0.650 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Salguero-Pazos, M.; Reyes-de-Cózar, S. Exploring the Relationship Between Electronic Device Use and Psychological Dimensions of Procrastination in University Students. Behav. Sci. 2026, 16, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010006

Salguero-Pazos M, Reyes-de-Cózar S. Exploring the Relationship Between Electronic Device Use and Psychological Dimensions of Procrastination in University Students. Behavioral Sciences. 2026; 16(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalguero-Pazos, María, and Salvador Reyes-de-Cózar. 2026. "Exploring the Relationship Between Electronic Device Use and Psychological Dimensions of Procrastination in University Students" Behavioral Sciences 16, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010006

APA StyleSalguero-Pazos, M., & Reyes-de-Cózar, S. (2026). Exploring the Relationship Between Electronic Device Use and Psychological Dimensions of Procrastination in University Students. Behavioral Sciences, 16(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs16010006