Emotion Regulation Modulates Affective Responses Without Altering Memory Traces: A Study of Negative Social Feedback from Acquaintances

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Feedback

1.2. The Role of Emotion Regulation

1.3. The Role of Depressive Symptoms

1.4. Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Stimulus Material

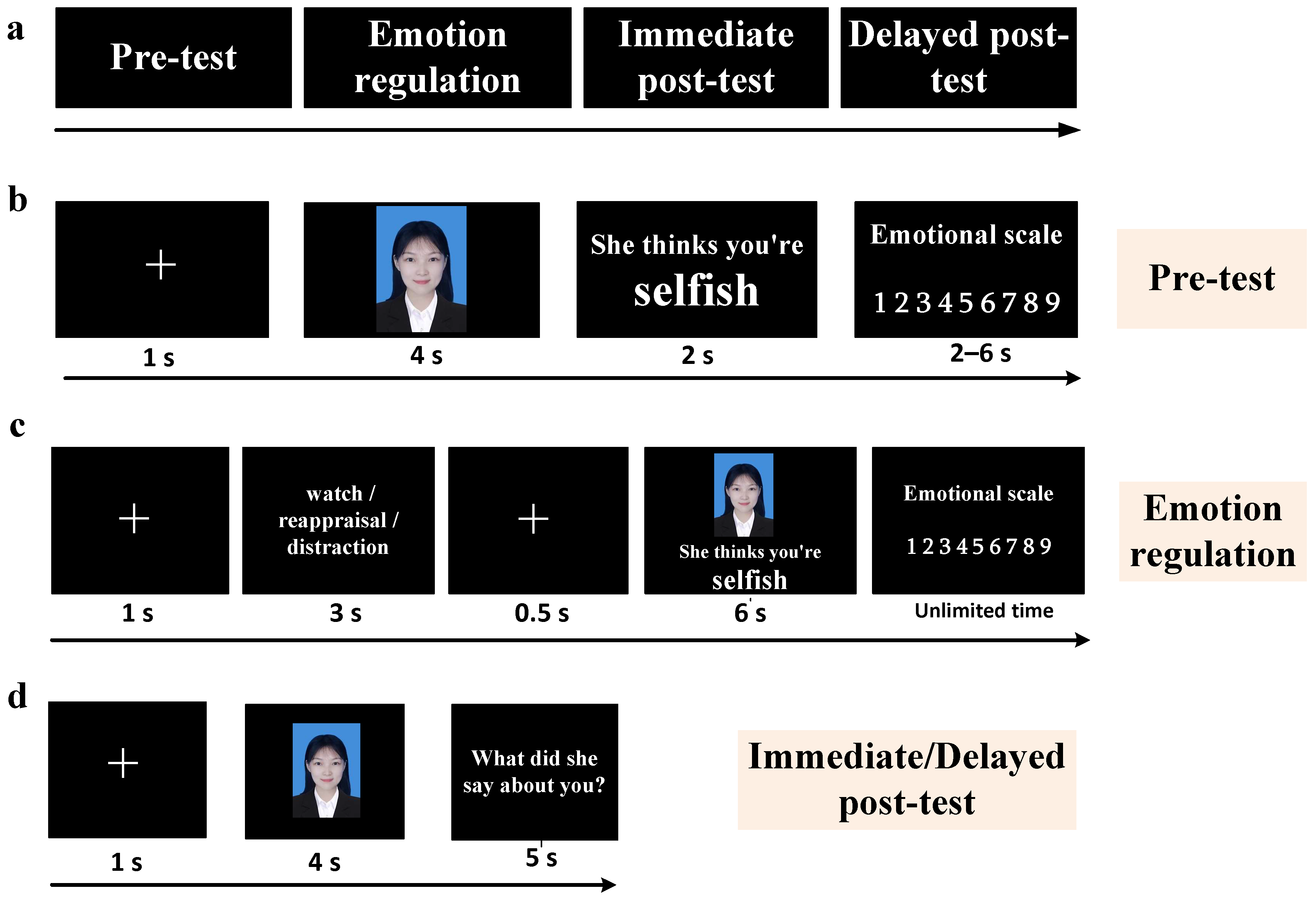

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

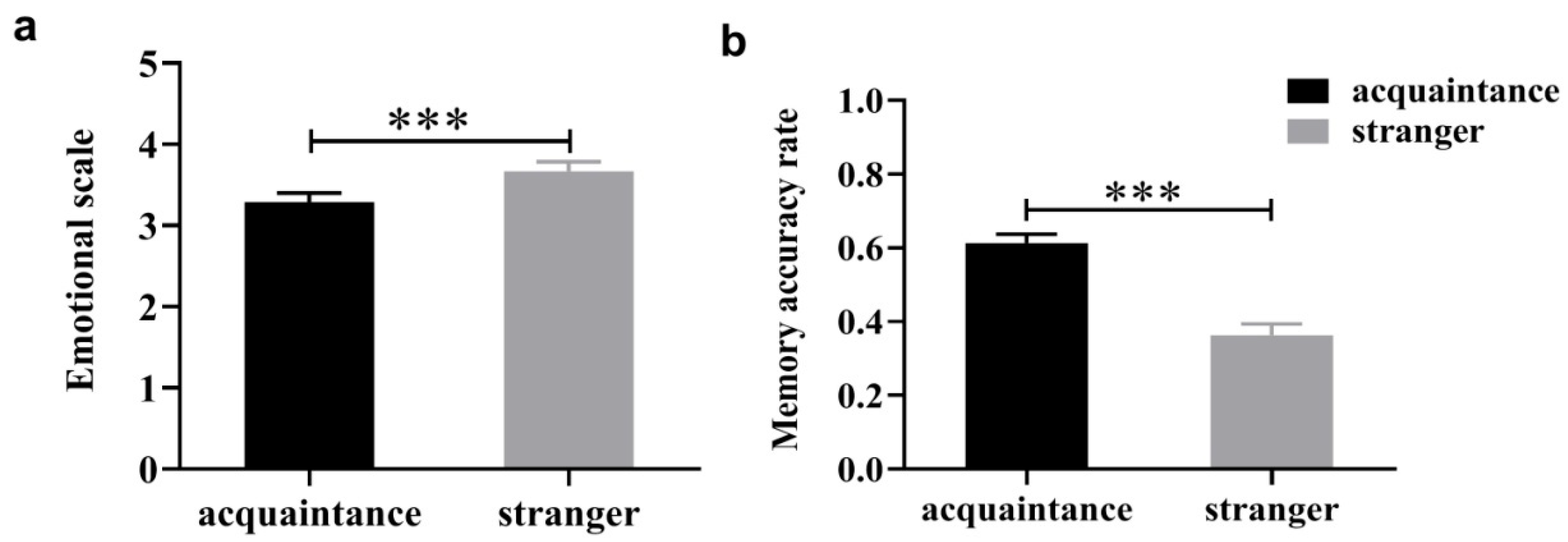

3.1. Emotional Scores and Memory Strength of Negative Social Feedback Sent to Different Groups of People

3.2. Effects of Emotion Regulation on Negative Social Feedback Sent by Acquaintances

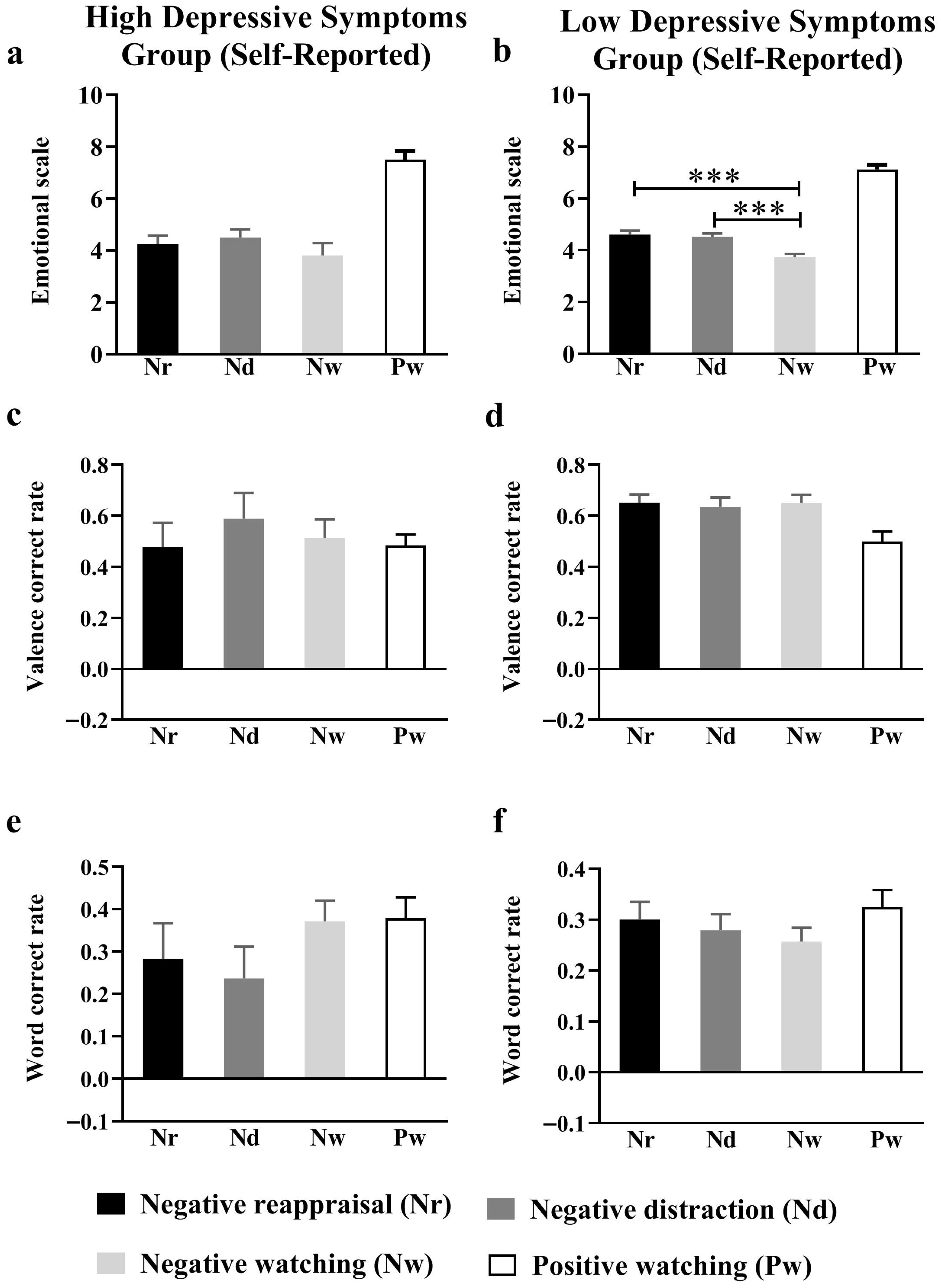

3.3. The Effect of Using Emotion Regulation Strategies on Sending Negative Social Feedback from Acquaintances in Groups with Self-Reported Different Levels of Depression Scores

4. Discussion

4.1. Negative Social Feedback Sent by Acquaintances Elicits Stronger Emotional Experiences and Is Harder to Forget

4.2. Effects of Emotion Regulation Strategies on Emotions and Memories Elicited by Negative Social Feedback from Acquaintances

4.3. Emotion Regulation Strategies Differ in Their Effectiveness in Moderating Negative Social Feedback in Self-Reported High- and Low-Depressive Symptoms Groups

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Sepulcre, J., Poulin, R., & Buckner, R. L. (2010). Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain’s default network. Neuron, 65(4), 550–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Muraven, M., & Tice, D. M. (1998). Ego depletion: Is the active self a limited resource? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1987). Beck depression inventory. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. [Google Scholar]

- Boemo, T., Nieto, I., Vazquez, C., & Sanchez-Lopez, A. (2022). Relations between emotion regulation strategies and affect in daily life: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessments. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 139, 104747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudner, E. G., Fareri, D. S., Shehata, S. G., & Delgado, M. R. (2023). Social feedback promotes positive social sharing, trust, and closeness. Emotion, 23(6), 1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bylsma, L. M. (2021). Emotion context insensitivity in depression: Toward an integrated and contextualized approach. Psychophysiology, 58(2), e13715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Boucher, H. C., & Tapias, M. P. (2006). The relational self revealed: Integrative conceptualization and implications for interpersonal life. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. L., & Liao, W. T. (2021). Emotion regulation in close relationships: The role of Individual differences and situational context. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 697901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. M., Li, S. J., Guo, T. Y., Xie, H., Xu, F., & Zhang, D. D. (2021). The role of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on voluntary forgetting of negative social feedback in depressed patients: A TMS study. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 10(53), 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cludius, B., Mennin, D., & Ehring, T. (2020). Emotion regulation as a transdiagnostic process. Emotion, 20(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craik, F. I. (2014). Effects of distraction on memory and cognition: A commentary. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X., Ding, Q., Yu, S., Zhang, S., & Li, X. (2024). The deficit in cognitive reappraisal capacity in individuals with anxiety or depressive disorders: Meta-analyses of behavioral and neuroimaging studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 114, 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, E. L., & Levine, L. J. (2013). Emotion regulation strategies that promote learning: Reappraisal enhances children’s memory for educational information. Child Development, 84(1), 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DePaulo, B. M., Blank, A. L., Swaim, G. W., & Hairfield, J. G. (1992). Expressiveness and expressive control. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disner, S. G., Beevers, C. G., Haigh, E. A. P., & Beck, A. T. (2011). Neural mechanisms of the cognitive model of depression. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 12(8), 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotson, V. M., McClintock, S. M., Verhaeghen, P., Kim, J. U., Draheim, A. A., Syzmkowicz, S. M., Gradone, A. M., Bogoian, H. R., & Wit, L. D. (2020). Depression and cognitive control across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 30(4), 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloff, B., Schmukle, S. C., Burns, L. R., & Schwerdtfeger, A. (2006). Spontaneous emotion regulation during evaluated speaking tasks: Associations with negative affect, anxiety expression, memory, and physiological responding. Emotion, 6(3), 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302(5643), 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emily, E. B., Nicole, J. L., Kate, H. B., Paul, J. B., & Richard, J. M. (2021). A single-session workshop to enhance emotional awareness and emotion regulation for graduate students: A pilot study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 28(3), 393–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erk, S., Mikschl, A., Stier, S., Ciaramidaro, A., Gapp, V., Weber, B., & Walter, H. (2010). Acute and sustained effects of cognitive emotion regulation in major depression. The Journal of Neuroscience, 30(47), 15726–15734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraley, R. C., Garner, J. P., & Shaver, P. R. (2000). Adult attachment and the defensive regulation of attention and memory: Examining the role of preemptive and postemptive defensive processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frey, A. L., Frank, M. J., & McCabe, C. (2021). Social reinforcement learning as a predictor of real-life experiences in individuals with high and low depressive symptomatology. Psychological Medicine, 51(3), 408–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J. J. (1998). Antecedent-and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J. J. (1999). Emotion and emotion regulation. In L. A. Pervin, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 525–552). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. P., Morey, R. A., Petty, C. M., Seth, S., Smoski, M. J., McCarthy, G., & LaBar, K. S. (2010). Staying cool when things get hot: Emotion regulation modulates neural mechanisms of memory encoding. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, A. S., Johnstone, T., Shackman, A. J., Light, S. N., Peterson, M. J., Kolden, G. G., Kalin, N. H., & Davidson, R. J. (2009). Reduced capacity to sustain positive emotion in major depression reflects diminished maintenance of fronto-striatal brain activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(52), 22445–22450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooker, C. I., Gyurak, A., Verosky, S. C., Miyakawa, A., & Ayduk, Ö. (2010). Neural activity to a partner’s facial expression predicts self-regulation after conflict. Biological Psychiatry, 67(5), 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivity, Y., & Huppert, J. D. (2016). Emotional reactions to facial expressions in social anxiety: A meta-analysis of self-reports. Emotion Review, 8(4), 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Xie, H., Zheng, Z., Chen, W., Xu, F., Hu, X., & Zhang, D. (2022). The causal role of the bilateral ventrolateral prefrontal cortices on emotion regulation of social feedback. Human Brain Mapping, 43(9), 2898–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liston, C., McEwen, B. S., & Casey, B. J. (2009). Psychosocial stress reversibly disrupts prefrontal processing and attentional control. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(3), 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McRae, K., Hughes, B., Chopra, S., Gabrieli, J. D. E., Gross, J. J., & Ochsner, K. N. (2010). The neural bases of distraction and reappraisal. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(2), 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nasso, S., Vanderhasselt, M. A., Schettino, A., & De Raedt, R. (2020). The role of cognitive reappraisal and expectations in dealing with social feedback. Emotion, 22(5), 982–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, B. D., Fitzgerald, D. A., Klumpp, H., Shankman, S. A., & Phan, K. L. (2015). Prefrontal engagement by cognitive reappraisal of negative faces. Behavioural Brain Research, 279, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochsner, K. N., Knierim, K., Ludlow, D. H., Hanelin, J., Ramachandran, T., Glover, G., & Mackey, S. C. (2004). Reflecting upon feelings: An fMRI study of neural systems supporting the attribution of emotion to self and other. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16, 1746–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, G., Simmons, A. N., Wu, J., Hahn, K. S., Tapert, S. F., Max, J. E., Paulus, M. P., Brown, G. G., Frank, G. K., Campbell-Sills, L., & Yang, T. T. (2012). Amygdala response and functional connectivity during emotion regulation: A study of 14 depressed adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 139(1), 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, B., Campbell, C. A., James, A. C., Murphy, S. E., Cooper, M. J., & Lau, J. Y. F. (2015). Cognitive reappraisal of peer rejection in depressed versus non-depressed adolescents: Functional connectivity differences. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 61, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappaport, B. I., & Barch, D. M. (2020). Brain responses to social feedback in internalizing disorders: A comprehensive review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 118, 784–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. M., Butler, E. A., & Gross, J. J. (2003). Emotion regulation in romantic relationships: The cognitive consequences of concealing feelings. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 20(5), 599–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. M., & Gross, J. J. (2000). Emotion regulation and memory: The cognitive costs of keeping one’s cool. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(3), 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J. M., & Gross, J. J. (2006). Personality and emotional memory: How regulating emotion impairs memory for emotional events. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(5), 631–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, C. C., & Fehr, E. (2014). The neurobiology of rewards and values in social decision making. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(8), 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppes, G., & Meiran, N. (2008). Divergent cognitive costs for online forms of reappraisal and distraction. Emotion, 8(6), 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somerville, L. H., Heatherton, T. F., & Kelley, W. M. (2006). Anterior cingulate cortex responds differentially to expectancy violation and social rejection. Nature Neuroscience, 9(8), 1007–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. N., Zhou, L. M., & Luo, Y. J. (2008). Compilation and evaluation of preliminary system of Chinese emotional words. Chinese Journal of Mental Health, 22(8), 608–612. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, C. W., Koban, L., Kross, E., Lindquist, M. A., Banich, M. T., Ruzic, L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., & Wager, T. D. (2014). Separate neural representations for physical pain and social rejection. Nature Communications, 5, 5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H., Hu, X., Mo, L., & Zhang, D. (2021). Forgetting positive social feedback is difficult: ERP evidence in a directed forgetting paradigm. Psychophysiology, 58(5), e13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H., Lin, X. Y., Hu, W. R., & Hu, X. Q. (2023). Emotion regulation promotes forgetting of negative social feedback: Behavioral and EEG evidence. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 55(6), 905–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H., Mo, L., Li, S., Liang, J., Hu, X., & Zhang, D. (2022). Aberrant social feedback processing and its impact on memory, social evaluation, and decision-making among individuals with depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 300, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilverstand, A., Parvaz, M. A., & Goldstein, R. Z. (2017). Neuroimaging cognitive reappraisal in clinical populations to define neural targets for enhancing emotion regulation. A systematic review. NeuroImage, 151, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, P.; Cheng, X.; Fan, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C. Emotion Regulation Modulates Affective Responses Without Altering Memory Traces: A Study of Negative Social Feedback from Acquaintances. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091294

Liu P, Cheng X, Fan M, Huang Z, Zhang C. Emotion Regulation Modulates Affective Responses Without Altering Memory Traces: A Study of Negative Social Feedback from Acquaintances. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091294

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Peng, Xin Cheng, Mengyao Fan, Zhichao Huang, and Chao Zhang. 2025. "Emotion Regulation Modulates Affective Responses Without Altering Memory Traces: A Study of Negative Social Feedback from Acquaintances" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091294

APA StyleLiu, P., Cheng, X., Fan, M., Huang, Z., & Zhang, C. (2025). Emotion Regulation Modulates Affective Responses Without Altering Memory Traces: A Study of Negative Social Feedback from Acquaintances. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1294. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091294