Association Between Trauma, Impulsivity, and Functioning in Suicide Attempters

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Sample

- Age of 18 years or older.

- Attendance at any of the specified clinical services within the past month due to a suicide attempt or emergency referral for suicidal ideation.

- Ability to understand and sign the informed consent form.

- Fluency in Spanish (or French in the French centers, though that sample was not utilized in this study), enabling comprehension of the information sheet, informed consent, assessments, and mobile application menus.

- Age under 18 years.

- Inability or unwillingness to provide informed and signed consent.

- Emergency situations where health status precluded obtaining written consent.

2.3. Measures (Used for This Study)

2.4. Procedure

- Recruitment: The attending psychiatrist or psychologist proposes the patient’s participation in the study. If the patient agrees, they sign the consent form and are included in the study.

- Baseline Interview: A trained psychologist conducts the initial interview and administers the aforementioned scales.

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

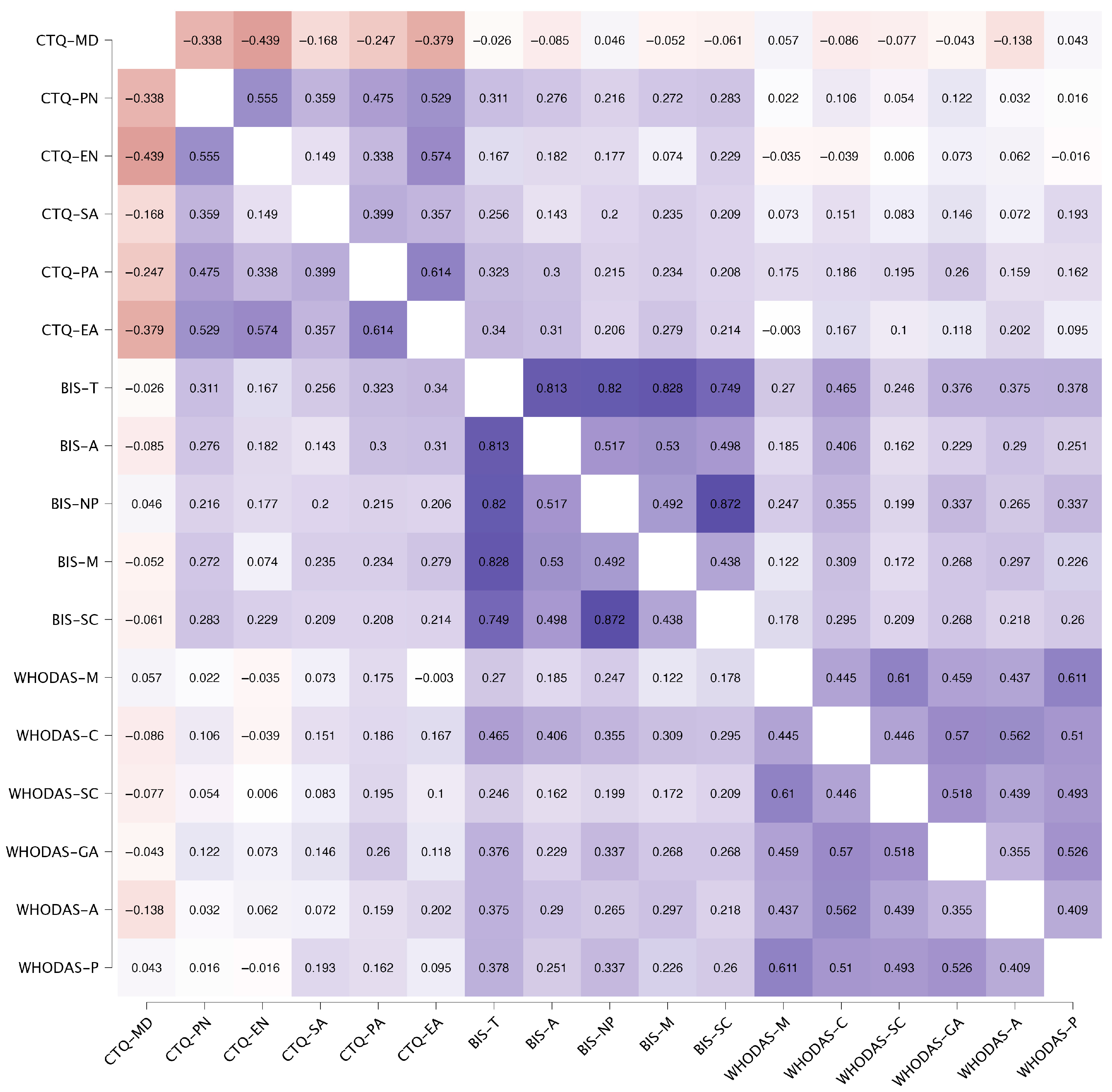

3.2. Correlation Between Variables

3.3. Factors Associated with Functioning

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographic Factors

4.2. Correlation Between Trauma and Impulsivity

4.3. Factors Predicting Functioning

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abascal-Peiró, S., Alacreu-Crespo, A., Peñuelas-Calvo, I., López-Castromán, J., & Porras-Segovia, A. (2023). Characteristics of single vs. multiple suicide attempters among adult population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Psychiatry Reports, 25(11), 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adserà, A., & Lozano, M. (2021). ¿Por qué las mujeres no tienen todos los hijos que dicen querer tener? Available online: https://elobservatoriosocial.fundacionlacaixa.org/es/-/por-que-las-mujeres-no-tienen-todos-los-hijos-que-dicen-querer-tener#:~:text=En%20Espa%C3%B1a%2C%20aproximadamente%20el%2019,se%20acercan%20m%C3%A1s%20al%2020%25 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Alameda, L., Ferrari, C., Baumann, P. S., Gholam-Rezaee, M., Do, K. Q., & Conus, P. (2015). Childhood sexual and physical abuse: Age at exposure modulates impact on functional outcome in early psychosis patients. Psychological Medicine, 45(13), 2727–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Esquivel, C., Francisco Sánchez-Anguiano, L., Arnaud-Gil, C. A., Hernández-Tinoco, J., Fernando Molina-Espinoza, L., & Rábago-Sánchez, E. (2014). Socio-demographic, clinical and behavioral characteristics associated with a history of suicide attempts among psychiatric outpatients: A case control study in a northern Mexican City. International Journal of Biomedical Science, 10(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anestis, M. D., Soberay, K. A., Gutierrez, P. M., Hernández, T. D., & Joiner, T. E. (2014). Reconsidering the link between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(4), 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baca-Garcia, E., Diaz-Sastre, C., García Resa, E., Blasco, H., Braquehais Conesa, D., Oquendo, M. A., Saiz-Ruiz, J., & De Leon, J. (2005). Suicide attempts and impulsivity. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 255(2), 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrigon, M. L., Porras-Segovia, A., Courtet, P., Lopez-Castroman, J., Berrouiguet, S., Pérez-Rodríguez, M. M., Artes, A., MEmind Study Group & Baca-Garcia, E. (2022). Smartphone-based Ecological Momentary Intervention for secondary prevention of suicidal thoughts and behaviour: Protocol for the SmartCrisis V.2.0 randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open, 12(9), e051807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behn, A., Vöhringer, P. A., Martínez, P., Domínguez, A. P., González, A., Carrasco, M. I., & Gloger, S. (2020). Validación de la versión en español del Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form en Chile, en una muestra de pacientes con depresión clínica [Validation of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form in Chile]. Revista Medica de Chile, 148(3), 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berrouiguet, S., Barrigón, M. L., Castroman, J. L., Courtet, P., Artés-Rodríguez, A., & Baca-García, E. (2019). Combining mobile-health (mHealth) and artificial intelligence (AI) methods to avoid suicide attempts: The Smartcrises study protocol. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolote, J. M., Fleischmann, A., De Leo, D., & Wasserman, D. (2004). Psychiatric diagnoses and suicide: Revisiting the evidence. Crisis, 25(4), 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, D., Hill, J., O’ryan, D., Udwin, O., Boyle, S., & Yule, W. (2004). Long-term effects of psychological trauma on psychosocial functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braquehais, M. D., Oquendo, M. A., Baca-García, E., & Sher, L. (2010). Is impulsivity a link between childhood abuse and suicide? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 51(2), 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambridge Dictionary. (2025). Functioning. Available online: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/functioning (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Hinesley, J., Chan, R. F., Aberg, K. A., Fairbank, J. A., Van Den Oord, E. J. C. G., & Costello, E. J. (2018). Association of childhood trauma exposure with adult psychiatric disorders and functional outcomes. JAMA Network Open, 1(7), e184493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornellà Canals, J., & Juárez López, J. R. (2014). Sintomatología del trastorno por déficit de atención con hiperactividad y su relación con el maltrato infantil: Predictor y consecuencia [Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms and their relationship with child abuse: Predictor and consequence]. Anales de Pediatria, 81(6), 398.e1–398.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotter, J., Kaess, M., & Yung, A. R. (2014). Childhood trauma and functional disability in psychosis, bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder: A review of the literature. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32(1), 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dal Santo, F., Carballo, J. J., Velasco, A., Jiménez-Treviño, L., Rodríguez-Revuelta, J., Martínez-Cao, C., Caro-Cañizares, I., de la Fuente-Tomás, L., Menéndez-Miranda, I., González-Blanco, L., García-Portilla, M. P., Bobes, J., & Sáiz, P. A. (2020). The mediating role of impulsivity in the relationship between suicidal behavior and early traumatic experiences in depressed subjects. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 538172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Castro, L., Arroyo-Belmonte, M., Suárez-Brito, P., Márquez-Caraveo, M. E., & Garcia-Andrade, C. (2024). Validation of the World Health Organization’s Disability Assessment Schedule 2.0 for children with mental disorders in specialized health-care services. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1415133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvir, Y., Ford, J. D., Hill, M., & Frazier, J. A. (2014). Childhood maltreatment, emotional dysregulation, and psychiatric comorbidities. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 22(3), 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezquerra, B., Alacreu-Crespo, A., Peñuelas-Calvo, I., Abascal-Peiró, S., Jiménez-Muñoz, L., Nicholls, D., Baca-García, E., & Porras-Segovia, A. (2023). Characteristics of single vs. multiple suicide attempters among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(10), 3405–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Fernández, A., Martínez-Cao, C., Sánchez-Fernández-Quejo, A., Bobes-Bascarán, T., Andreo-Jover, J., Ayad-Ahmed, W., Cebriá, A. I., Díaz-Marsá, M., Garrido-Torres, N., Gómez, S., González-Pinto, A., Grande, I., Iglesias, N., March, K. B., Palao, D. J., Pérez-Díez, I., Roberto, N., Ruiz-Veguilla, M., de la Torre-Luque, A., … García-Portilla, M. P. (2024). Validation of the Spanish Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form in adolescents with suicide attempts. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1378486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. (2018). Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 359 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet, 392(10159), 1859–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giner, L., Jaussent, I., Olié, E., Béziat, S., Guillaume, S., Baca-Garcia, E., Lopez-Castroman, J., & Courtet, P. (2014). Violent and serious suicide attempters: One step closer to suicide? The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(3), e191–e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez, A., Gallardo-Pujol, D., Pereda, N., Arntz, A., Bernstein, D. P., Gaviria, A. M., Labad, A., Valero, J., & Gutiérrez-Zotes, J. A. (2013). Initial validation of the Spanish childhood trauma questionnaire-short form: Factor structure, reliability and association with parenting. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(7), 1498–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística [INE]. (2023). Movimiento natural de la población/indicadores demográficos básicos 2023. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/Prensa/es/MNP2023.htm (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Jacob, L., Thoumie, P., Haro, J. M., & Koyanagi, A. (2020). The relationship of childhood sexual and physical abuse with adulthood disability. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 63(4), 332–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, E., Arias, B., Castellví, P., Goikolea, J. M., Rosa, A. R., Fañanás, L., Vieta, E., & Benabarre, A. (2012). Impulsivity and functional impairment in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(3), 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, O. (2025). Exploring childhood adversity, impulsivity, and cognitive functioning within forensic populations [DForenPsy thesis, University of Nottingham]. [Google Scholar]

- Kendler, K. S., Ohlsson, H., Mościcki, E. K., Sundquist, J., Edwards, A. C., & Sundquist, K. (2023). Genetic liability to suicide attempt, suicide death, and psychiatric and substance use disorders on the risk for suicide attempt and suicide death: A Swedish national study. Psychological Medicine, 53(4), 1639–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E. D., Qiu, T., & Saffer, B. Y. (2017). Recent advances in differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(1), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kockler, T. R., & Stanford, M. S. (2008). Using a clinically aggressive sample to examine the association between impulsivity, executive functioning, and verbal learning and memory. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 23(2), 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Luong, L., Lachaud, J., Edalati, H., Reeves, A., & Hwang, S. W. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and related outcomes among adults experiencing homelessness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. Public Health, 6(11), e836–e847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R. T. (2019). Childhood maltreatment and impulsivity: A meta-analysis and recommendations for future study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(2), 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Morinigo, J. D., Boldrini, M., Ricca, V., Oquendo, M. A., & Baca-García, E. (2021). Aggression, impulsivity and suicidal behavior in depressive disorders: A comparison study between New York City (US), Madrid (Spain) and Florence (Italy). Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(14), 3057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P. E., Mechawar, N., & Turecki, G. (2017). Neuropathology of suicide: Recent findings and future directions. Molecular Psychiatry, 22(10), 1395–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Loredo, V., Fernández-Hermida, J. R., Fernández-Artamendi, S., Carballo, J. L., & García-Rodríguez, O. (2015). Directores Asociados/Associate Editors: Spanish adaptation and validation of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale for early adolescents (BIS-11-A). International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 15(2), 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, A. L. (2025). Early adversity, impulsivity, and health behaviors [Ph.D. thesis, University of Kentucky]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M. F. (2025). El mapa de La Fertilidad En Europa. Available online: https://es.statista.com/grafico/28864/numero-promedio-de-hijos-nacidos-vivos-por-mujer-en-europa/#:~:text=Demograf%C3%ADa,-Autor%20Mar%C3%ADa%20Florencia&text=En%20Espa%C3%B1a%2C%20cada%20mujer%20podr%C3%ADa,en%20los%201%2C38%20ni%C3%B1os.&text=Esta%20infograf%C3%ADa%20muestra%20la%20tasa%20de%20fertilidad%20de%20Europa%20en%202023 (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Miranda-Mendizabal, A., Castellví, P., Parés-Badell, O., Alayo, I., Almenara, J., Alonso, I., Blasco, M. J., Cebrià, A., Gabilondo, A., Gili, M., Lagares, C., Piqueras, J. A., Rodríguez-Jiménez, T., Rodríguez-Marín, J., Roca, M., Soto-Sanz, V., Vilagut, G., & Alonso, J. (2019). Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. International Journal of Public Health, 64(2), 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J. M., Becker-Blease, K. A., & Soicher, R. N. (2021). Child sexual abuse, academic functioning and educational outcomes in emerging adulthood. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 30(3), 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Manso, J. M., García-Baamonde, M. E., de la Rosa Murillo, M., Blázquez-Alonso, M., Guerrero-Barona, E., & García-Gómez, A. (2022). Differences in executive functions in minors suffering physical abuse and neglect. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(5–6), NP2588–NP2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabinger, A. B., Panzenhagen, A. C., Dahmer, T., Almeida, R. F., Dias, A. U., Pereira, B. F. B., Pedro, C. W., Rodrigues, G. S., Adão, I. K., Robini, P. H. O., Silva, J. S., Rocha, R., Dantas, R. P., Moreira, J. C. F., Capp, E., & Shansis, F. M. (2024). Early-life trauma, impulsivity and suicide attempt: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M., & Global Burden of Disease Self-Harm Collaborators. (2019). Global, regional, and national burden of suicide mortality 1990 to 2016: Systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. BMJ (Clinical Research Edition), 364, l94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M. K. (Ed.). (2009). Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment, and treatment. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oquendo, M. A., Baca-Garcia, E., Graver, R., Morales, M., Montalvan, V., & Mann, J. (2001). Spanish adaptation of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11). European Journal of Psychiatry, 15, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Papazian, O., Alfonso, I., & García, V. (2002). Efecto de la discontinuación del metifenidato al comienzo de la adolescencia sobre el trastorno por déficit de atención en la edad adulta [The effect of discontinuation of methylphenidate at adolescence onset on adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder]. Revista de neurologia, 35(1), 24–28. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Balaguer, A., Peñuelas-Calvo, I., Alacreu-Crespo, A., Baca-García, E., & Porras-Segovia, A. (2022). Impulsivity as a mediator between childhood maltreatment and suicidal behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 151, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard-Lepouriel, H., Kung, A. L., Hasler, R., Bellivier, F., Prada, P., Gard, S., Ardu, S., Kahn, J. P., Dayer, A., Henry, C., Aubry, J. M., Leboyer, M., Perroud, N., & Etain, B. (2019). Impulsivity and its association with childhood trauma experiences across bipolar disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and borderline personality disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 244, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahle, B. W., Reavley, N. J., Li, W., Morgan, A. J., Yap, M. B. H., Reupert, A., & Jorm, A. F. (2022). The association between adverse childhood experiences and common mental disorders and suicidality: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. European child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(10), 1489–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Gómez, S., Vera-Varela, C., Alacreu-Crespo, A., Perea-González, M. I., Guija, J. A., & Giner, L. (2024). Impulsivity in fatal suicide behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological autopsy studies. Psychiatry Research, 337, 115952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, Z. A. E., El Shinnawy, H. A., Eltawil, M. E., Elnawawy, Y., Rashad, W., & Saadeldin Mohammed, M. (2019). Global functioning and suicide risk in patients with depression and comorbid borderline personality disorder. Neurology Psychiatry and Brain Research, 31, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, D. P., Realo, A., Voracek, M., & Allik, J. (2008). Why can’t a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94(1), 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turecki, G., Brent, D. A., Gunnell, D., O’Connor, R. C., Oquendo, M. A., Pirkis, J., & Stanley, B. H. (2019). Suicide and suicide risk. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers, 5(1), 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstün, T. B., Kostanjsek, N., Chatterji, S., & Rehm, J. (2010). Measuring health and disability: Manual for WHO Disability Assessment Schedule WHODAS 2.0. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- van Spijker, B. A. J., Batterham, P. J., Calear, A. L., Wong, Q. J. J., Werner-Seidler, A., & Christensen, H. (2020). Self-reported disability and quality of life in an online Australian community sample with suicidal thoughts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. World Health Organization. ISBN 9241545429. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241564779. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. (2018). National suicide prevention strategies progress, examples and indicators. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/national-suicide-prevention-strategies-progress-examples-and-indicators (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- WHO. (2025). Suicide. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- World Medical Association. (2013). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA, 310(20), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | Mean (SD) | Missing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 292 | 41.42 (14.37) | 1 | ||

| Gender | Male | 101 | 34.47 | ||

| Female | 192 | 65.53 | |||

| Marital Status | Single | 125 | 42.81 | 1 | |

| Married/living with partner > 6 months | 101 | 34.59 | |||

| Divorced | 59 | 20.21 | |||

| Widowed | 7 | 2.40 | |||

| Lives with | Couple | 98 | 35.13 | 14 | |

| Family | 95 | 34.05 | |||

| Alone | 58 | 20.79 | |||

| Institution | 1 | 0.36 | |||

| Have children? | None | 166 | 56.85 | 1 | |

| 1 | 53 | 18.51 | |||

| 2 | 51 | 17.47 | |||

| 3 | 16 | 5.48 | |||

| 4 or more | 6 | 2.05 | |||

| Impulsivity | Attentional | 221 | 20.15 (4.51) | 72 | |

| Motor | 201 | 24.15 (5.57) | 92 | ||

| Non-planning | 211 | 26.00 (5.47) | 82 | ||

| Trauma | Emotional Abuse | 289 | 13.38 (6.27) | 4 | |

| Physical Abuse | 284 | 8.89 (5.46) | 9 | ||

| Sexual Abuse | 278 | 8.91 (5.70) | 15 | ||

| Emotional Neglect | 292 | 13.50 (5.20) | 1 | ||

| Physical Neglect | 290 | 8.68 (4.21) | 3 | ||

| Functioning | Cognition | 276 | 29.67 (22.01) | 17 | |

| Mobility | 277 | 21.10 (23.98) | 16 | ||

| Self-care | 283 | 17.17 (22.00) | 10 | ||

| Getting along | 196 | 34.23 (29.63) | 97 | ||

| Life Activities | 281 | 37.92 (30.54) | 12 | ||

| Participation | 255 | 41.95 (20.42) | 38 |

| Variables | df | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1 | 0.990 | 0.974–1.007 | 0.254 | |

| Gender | Male | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 1 | 1.229 | 0.759–1.990 | 0.402 | |

| Marital Status | 3 | 0.681 | |||

| Married/living with partner > 6 months | 1.00 | ||||

| Single | 1 | 1.156 | 0.671–1.991 | 0.602 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 1.202 | 0.611–2.367 | 0.593 | |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.488 | 0.103–2.297 | 0.364 | |

| Lives with | Couple | 1 | 1.144 | 0.683–1.915 | 0.609 |

| Family | 1 | 1.196 | 0.712–2.007 | 0.499 | |

| Alone | 1.385 | 0.744–2.577 | 0.304 | ||

| Have children? | 1 | 0.955 | 0.787–1.159 | 0.639 | |

| Impulsivity (Barrat Total) | 1 | 1.053 | 1.025–1.081 | <0.001 | |

| Trauma | Emotional Neglect | 1 | 0.996 | 0.951–1.042 | 0.852 |

| Physical Neglect | 1 | 0.990 | 0.935–1.048 | 0.742 | |

| Sexual Abuse | 1 | 1.056 | 1.008–1.106 | 0.021 | |

| Physical Abuse | 1 | 1.058 | 1.009–1.110 | 0.021 | |

| Emotional Abuse | 1 | 1.021 | 0.982–1.061 | 0.289 | |

| Minimization/denial | 1 | 1.051 | 0.968–1.141 | 0.234 | |

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trauma | Emotional neglect | 0.991 | 0.946–1.038 | 0.713 |

| Emotional Abuse | 1.016 | 0.977–1057 | 0.425 | |

| Sexual abuse | 1.051 | 1.003–1.103 | 0.039 | |

| Physical abuse | 1.062 | 1.012–1.114 | 0.015 | |

| Impulsivity (Total Barrat) | 1.051 | 1.023–1.080 | <0.001 | |

| Model | B | SE | Wald | df | OR | CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.008 | 0.347 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.992 | 0.502–1.959 | 0.981 |

| Age | −0.014 | 0.012 | 1.304 | 1 | 0.986 | 0.962–1.010 | 0.254 |

| Barrat Total | 0.050 | 0.015 | 10.986 | 1 | 1.052 | 1.021–1.083 | <0.001 |

| Physical abuse | 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.728 | 1 | 1.033 | 0.959–1.111 | 0.393 |

| Sexual Abuse | 0.027 | 0.037 | 0.510 | 1 | 0.974 | 0.905–1.047 | 0.475 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Escobedo-Aedo, P.J.; Porras-Segovia, A.; Barrigón, M.L.; Courtet, P.; López-Castroman, J.; Baca-Garcia, E. Association Between Trauma, Impulsivity, and Functioning in Suicide Attempters. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091262

Escobedo-Aedo PJ, Porras-Segovia A, Barrigón ML, Courtet P, López-Castroman J, Baca-Garcia E. Association Between Trauma, Impulsivity, and Functioning in Suicide Attempters. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091262

Chicago/Turabian StyleEscobedo-Aedo, Paula Jhoana, Alejandro Porras-Segovia, Maria Luisa Barrigón, Philippe Courtet, Jorge López-Castroman, and Enrique Baca-Garcia. 2025. "Association Between Trauma, Impulsivity, and Functioning in Suicide Attempters" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091262

APA StyleEscobedo-Aedo, P. J., Porras-Segovia, A., Barrigón, M. L., Courtet, P., López-Castroman, J., & Baca-Garcia, E. (2025). Association Between Trauma, Impulsivity, and Functioning in Suicide Attempters. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091262