Further Validation Study of the Gender-Specific Binary Depression Screening Version (GIDS-15) and Investigation of Intervention Effects

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aims of the Current Study

- (1)

- What are the psychometric characteristics of the GIDS-15 in this sample?

- (2)

- How sensitive to change is the screening version of the GIDS-15 compared to an already established depression measurement instrument?

- (3)

- What are the sex differences in the intervention and waiting control groups over time in the total score of the screening version?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Gender-Specific Binary Depression Screening Version (GIDS-15; Pellowski et al., 2025)

2.2.2. Additional Assessments

Center for Epidemiological Studies for Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977)

Anxiety Subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A; Zigmond & Snaith, 1983)

Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Berle et al., 2011)

Insomnia Severity Index (ISI; Bastien et al., 2001)

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al., 1993)

Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology-Clinican Rating (QIDS-CR 16; Rush et al., 2003)

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD-24; Rush et al., 2003)

2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Research Question 1

3.2. Research Question 2

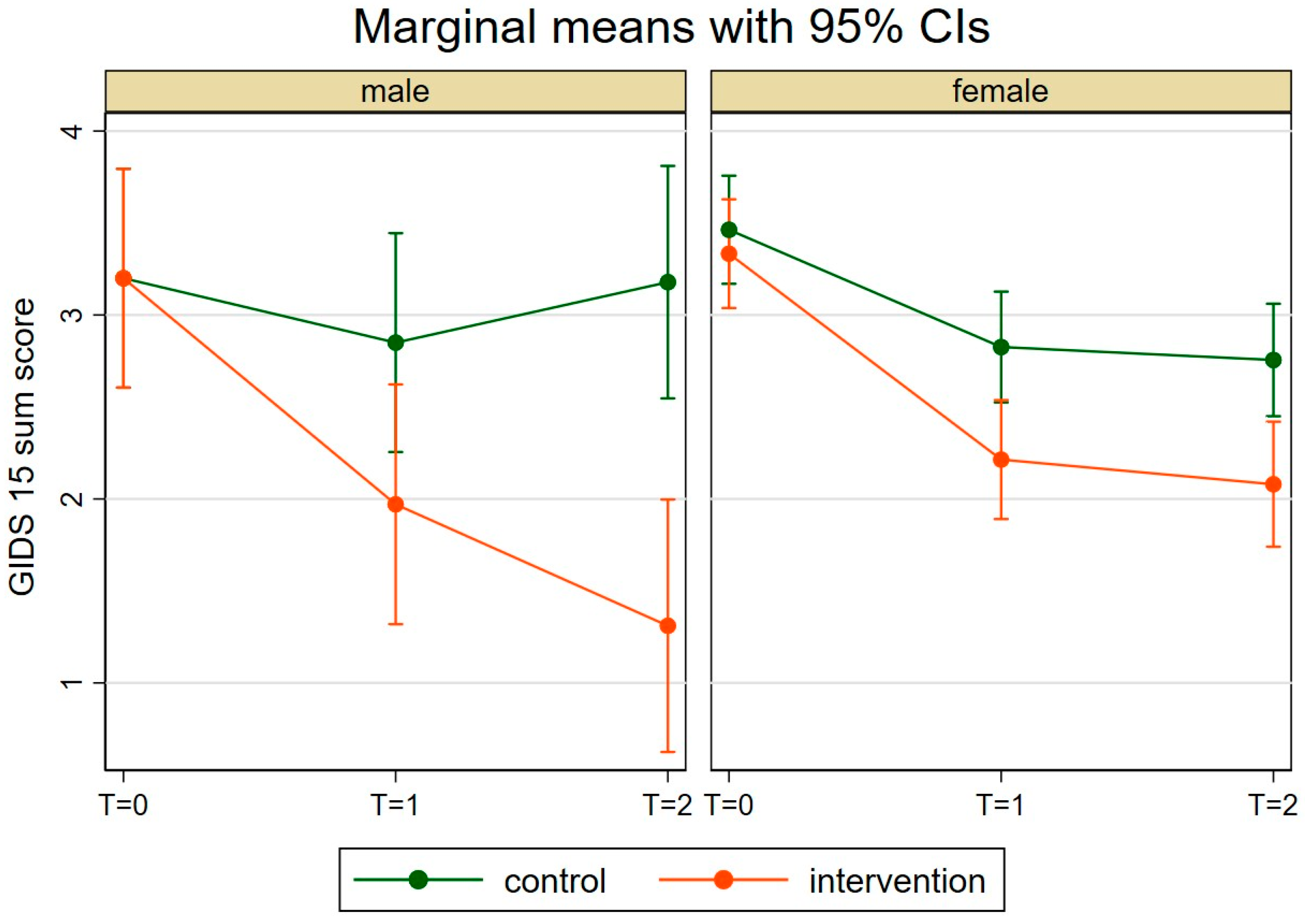

3.3. Research Question 3

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Question 1

4.2. Research Question 2

4.3. Research Question 3

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Addis, M. E. (2008). Gender and depression in men. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15(3), 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revision). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text revision). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C. H., Vallières, A., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, E., Czerwinski, F., & Reifegerste, D. (2017). Gender-specific determinants and patterns of online health information seeking: Results from a representative German health survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(4), e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K., & Herling, C. (2017). Der Einfluss von Gender im Entwicklungsprozess von digitalen Artefakten. GENDER: Zeitschrift für Geschlecht, Kultur und Gesellschaft, 9(3), 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berle, D., Starcevic, V., Moses, K., Hannan, A., Milicevic, D., & Sammut, P. (2011). Preliminary validation of an ultra-brief version of the Penn State Worry Questinnaire. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(4), 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Buntrock, C., Ebert, D. D., Lehr, D., Riper, H., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Berking, M. (2015). Effectiveness of a web-based cognitive behavioural intervention for subthreshold depression: Pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buntrock, C., Ebert, D. D., Lehr, D., Smit, F., Riper, H., Berking, M., & Cuijpers, P. (2016). Effect of a web-based guided self-help intervention for prevention of major depression in adults with subthreshold depression: A randomised clinical trial. JAMA, 315, 1854–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Call, J. B., & Shafer, K. (2018). Gendered manifestations of depression and help seeking among men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, A., Wilson, C. J., Caputi, P., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2016). Symptom endorsement in men versus women woth a diagnosis of depression: A differential item functioning approach. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 62, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, A., Wilson, C. J., Kavanagh, D. J., & Caputi, P. (2017). Differences in the expression of symptoms in men versus women with depression: A systematic review and meta analysis. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 25, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, S. V., & Rabinowitz, F. E. (2000). Men and depression: Clinical and empirical perspectives. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P., de Graaf, R., & van Dorsselaer, S. (2004). Minor depression: Risk profiles, functional disability, health care use and risk of developing major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 79, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, L., Fischer, M., & Kaprowski, D. (2024). „Männlich”, „weiblich”, „divers”—Eine kritische Auseinandersetzung mit der Erhebung von Geschlecht in der quantitativ-empirischen Sozialforschung. [A critival examination of measures for sex/gender in quantitative empirical social research]. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 53(4), 364–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieck, A., Morin, C. M., & Backhaus, J. (2018). A German version of the insomnia severity index. Somnologie, 22, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Zurilla, T. J., & Goldfried, M. R. (1971). Problem solving and behavior modification. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 78(1), 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, W. W., Badawi, M., & Melton, B. (1995). Prodromes and precursors: Epidemiologic data for primary prevention of disorders with slow onset. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebert, D. D., Buntrock, C., Lehr, D., Smit, F., Riper, H., Baumeister, H., Cuijpers, P., & Berking, M. (2018). Effectiveness of web- and mobile-based treatment of subthreshold depression with adherence-focused guidance: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Behavior Therapy, 49(1), 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, K., Seidler, Z. E., King, K., Oliffre, J. L., Robertson, S., & Rice, S. M. (2022). Men’s anxiety, why it matters, and what is needed to limit its risk for male suicide. Discover Psychology, 2(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, E., Prien, R. F., Jarrett, R. B., Keller, M. B., Kupfer, D. J., Lavori, P. W., Rush, A. J., & Weissman, M. M. (1991). Conzeptualization and rationale for consensus definitions of terms in major depressive disorder. Remission, recovery relapse, and recurrence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedel, E., Abels, I., Henze, G.-I., Hearing, S., Buspavanich, P., & Stadler, T. (2024). Die Depression im Spannungsfeld der Geschlechterrollen. Nervenarzt, 95(4), 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, M., Sprenger, A. A., Illing, S., Adriaanse, M. C., Albert, S. M., Allart, E., Almeida, O. P., Basanovic, J., van Bastelaar, K. M. P., Batterham, P. J., Baumeister, H., Berger, T., Blanco, V., Bø, R., Casten, R. J., Chan, D., Christensen, H., Ciharova, M., Cook, L., … Ebert, D. D. (2025). Psychological intervention in individuals with subthreshold depression: Individual participant data meta-analysis of treatment effects and moderators. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinz, A., & Schwarz, R. (2001). Angst und Depression in der Allgemeinbevölkerung: Eine Normierungsstudie zur Hospital anxiety and depression scale. [Anxiety and depression in the general population: Standardised values of the hospital anxiety and depression scale]. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie, 51(5), 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igl, W., Zwingmann, C., & Faller, H. (2006). Änderungssensitivität von Fragebogen zur Erfassung der subjektiven Gesundheit—Ergebnisse einer prospektiven vergleichenden Studie. Die Rehabilitation, 45(4), 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J., & Charney, D. (2000). Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 12(1), 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magovcevic, M., & Addis, M. E. (2008). The masculine depression scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 9, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L. A., Neighbors, H. W., & Griffith, D. M. (2013). The experience of symptoms of depression in men vs women: Analysis of the national comorbidity survey replication. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(10), 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, D. C., Cuijpers, P., & Lehmann, K. (2011). Supportive accountability: A model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(1), e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M., Jackl, A., & Weissbach, L. (2022). Gendersensitives Depressionsscreening (GSDS)—Befunde zur weiteren Validierung eines neues Selbstbeurteilungsinstruments. [Gender-sensitive depression screening (GSDS)—Further validation of a new self-rating instrument]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 49(7), 367–374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M., & Mühleck, J. (2020). Konstruktion und vorläufige Validierung eines gendersensitiven Depressionsscreenings (GSDS). [Development and preliminary validation of a gender-sensitive depression screening (GSDS)]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M., & Yücel, M. (2010). Male depression in females? Journal of Affective Disorders, 121(1–2), 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliffre, J. L., & Phillips, M. J. (2008). Men, depression and masculinities: A review and recommendations. Journal of Men’s Health, 5(3), 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østergaard, S. D., Seidler, Z., & Rice, S. (2023). The ICD-11 opens the door for overdue improved identificaion of depression in men. World Psychiatry, 22(3), 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G., & Brotchie, H. (2010). Gender differences in depression. International Review of Psychiatry, 22, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellowski, J. S., Ebert, D. D., & Christiansen, H. (2025). Validation of a gender-specific binary depression screening version (GIDS-15) in two German samples. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1469436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reins, J. A., Buntrock, C., Zimmermann, J., Grund, S., Harrer, M., Lehr, D., Baumeister, H., Weisel, K., Domhardt, M., Imamura, K., Kawakami, N., Spek, V., Nobis, S., Snoek, F., Cuijpers, P., Klein, J. P., Moritz, S., & Ebert, D. D. (2021). Efficacy and Moderators of Internet-based interventions in adults with subthreshold depression: An individual participant data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 90(2), 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, S. M., Fallon, B. J., Aucote, H. M., & Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2013). Development and preliminary validation of the male depression risk scale: Furthering the assessment of depressin in men. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, S. M., Seidler, Z., Kealy, D., Ogrodniczuk, J., Zajac, I., & Oliffre, J. (2022). Men’s depression, externalizing, and DSM-5-TR: Primary signs and symptoms of co-occurring symptoms? Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 30(5), 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roniger, A., Späth, C., Schweiger, U., & Klein, J. P. (2015). A psychometric evaluation of the German version of the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-SR16) in outpatients with depression. Fortschritte der Neurologie Psychiatrie, 83(12), e17–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucci, P., Gheradi, S., Tansella, M., Piccinelli, M., Berardi, D., Bisoffi, G., Corsino, M. A., & Pini, S. (2003). Subthreshold psychiatric disorders in primary care: Prevalence and associated characteristics. Journal of Affective Disorders, 76, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumpf, H. J., Hapke, U., Meyer, C., & John, U. (2002). Screening for alcohol use disorders and at-risk drinking in the general population: Psychometric performance of three questionnaires. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 37(3), 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, A. J., Rivedi, M. H., Ibrahim, H. M., Carmody, T. J., Arnow, B., Klein, D. N., Markowitz, J. C., Ninan, P. T., Kornstein, S., Manber, R., Thase, M. E., Kocsis, J. H., & Keller, M. B. (2003). The 16-item quick inventory of depressive symptomatology (QIDS), clinican rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry, 54(5), 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutz, W. (1999). Improvement of care for people suffering from depression: The need for comprehensive education. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 14, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutz, W., von Knorring, L., Pihlgren, H., Rihmer, Z., & Wålinder, J. (1995). Prevention of male suicides: Lessons from Gotland study. The Lancet, 345, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, J. B., Asland, O. G., Babor, T. F., de la Fuente, J. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, V., Nyklicek, I., Smits, N., Cuijpers, P., Riper, H., Keyzer, J., & Pop, V. (2007). Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold depres sion in people over 50 years old: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1797–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., & Williams, J. B. (1999). Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. JAMA, 282, 1737–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. (2023). Stata: Release 18. StataCorp LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Topper, M., Emmelkamp, P. M., Watkins, E., & Ehring, T. (2014). Development and assessment of brief versions of the Penn state worry questionnaire and the ruminative response scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 53(4), 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, M. H., Rush, A. J., Ibrahim, H. M., Carmody, T. J., Biggs, M. M., Suppes, T., Crismon, M. L., Shores-Wilson, K., Toprac, M. G., Dennehy, E. B., Witte, B., & Kashner, T. M. (2004). The inventory of depressive symptomatology, clinician rating (IDS-C) and self-report (IDS-SR), and the quick inventory of depressive symptomatology, clinician rating (QIDS-C) and self-report (QIDS-SR) in public sector patients with mood disorders: A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine, 34(1), 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- von Zimmermann, C., Hübner, M., Mühle, C., Müller, C. P., Weinland, C., Kornhuber, J., & Lenz, B. (2024). Masculine depression and its problem behaviors: Use alcohol and drugs, work hard, and avoid psychiatry! European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 274(2), 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, S. J., Muzik, M., Deligiannidis, K. M., Ammerman, R. T., Guille, C., & Flynn, H. A. (2016). Gender differences in suicidal risk factors among individuals with mood disorders. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 5, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D., Pjrek, E., & Kasper, S. (2005). Anger attacks in depression—Evidence for a male depressive syndrome. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 74, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y. J., Ho, M. R., Wang, S. Y., & Miller, I. S. (2017). Meta-analyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. (2022). International classification of diseases (11th revision). Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/2025-01/mms/en#1563440232 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zülke, A. E., Kersting, A., Dietrich, S., Luck, T., Riedel-Heller, S. G., & Stengler, K. (2018). Screeninginstrumente zur Erfassung von männerspezifischen Symptomen der unipolaren Depression—Ein kritischer Überblick. [Screening instruments for the detection of male-specific symptoms of unipolar depression—A critical overview]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 45(4), 178–187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | Intervention Group (N = 101) | Control Group (N = 102) | Total Sample (N = 203) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men | 20 (19.8%) | 20 (19.6%) | 40 (19.7%) |

| Women | 81 (80.2%) | 82 (80.4%) | 163 (80,3%) |

| Age | 44.65 (11.71) | 43.75 (11.84) | 44.20 (11.75) |

| Relationship | |||

| Single | 26 (25.7%) | 28 (27.5%) | 54 (26.6%) |

| Married or cohabiting | 65 (64.4%) | 53 (52.0%) | 118 (58.1%) |

| Divorced or separated | 9 (8.9%) | 20 (19.6%) | 29 (14.3%) |

| widowed | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Level of education | |||

| Low (primary) | 1 (1.0%) | 3 (2.9%) | 4 (2.0%) |

| Middle (secondary) | 16 (15.8%) | 16 (15.7%) | 32 (15.8%) |

| High (A-level or higher) | 84 (83.2%) | 83 (81.4%) | 167 (82.3%) |

| Employment status | |||

| Employed | 89 (88.1%) | 87 (85.3%) | 176 (86.7%) |

| Unemployed or seeking work | 2 (2.0%) | 4 (3.9%) | 6 (3.0%) |

| On sick leave | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.0%) | 2 (1.0%) |

| Non-working | 10 (9.9%) | 9 (8.8%) | 19 (9.4%) |

| Measurement Time | Group | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| T0 | Complete sample | 0.61 |

| IG | 0.60 | |

| WG | 0.63 | |

| T1 | Complete sample | 0.74 |

| IG | 0.75 | |

| WG | 0.71 | |

| T2 | Complete sample | 0.74 |

| IG | 0.75 | |

| WG | 0.71 |

| Self-Assessment | Clinician Ratings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-Assessment | GIDS-15 | CES-D | HADS-A | PSWQ | ISI | AUDIT | QIDS-CR 16 | HRSD-24 |

| GIDS-15 | 1 | |||||||

| CES-D | 0.47 ** | 1 | ||||||

| HADS-A | 0.20 ** | 0.37 ** | 1 | |||||

| PSWQ | 0.29 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.54 ** | 1 | ||||

| ISI | 0.15 * | 0.28 ** | 0.13 | 0.20 ** | 1 | |||

| AUDIT | 0.10 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.14 * | −0.00 | 1 | ||

| Clinician ratings | ||||||||

| QIDS-CR 16 | 0.41 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.06 | 1 | |

| HRSD-24 | 0.34 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.39 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.00 | 0.81 ** | 1 |

| Group | Comparison of the Points in Time | GIDS-15 [95% CI] | CES-D [95% CI] | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IG | T0-T1 | 0.80 [0.55–1.05] | 1.19 [0.91–1.48] | 0.007 |

| IG | T0-T2 | 0.87 [0.59–1.14] | 1.12 [0.82–1.411] | 0.091 |

| WG | T0-T1 | 0.40 [0.19–0.61] | 0.54 [0.33–0.75] | 0.197 |

| WG | T0-T2 | 0.40 [0.18–0.61] | 0.39 [0.18–0.61] | 0.955 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pellowski, J.S.; Wiessner, C.; Buntrock, C.; Christiansen, H. Further Validation Study of the Gender-Specific Binary Depression Screening Version (GIDS-15) and Investigation of Intervention Effects. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091253

Pellowski JS, Wiessner C, Buntrock C, Christiansen H. Further Validation Study of the Gender-Specific Binary Depression Screening Version (GIDS-15) and Investigation of Intervention Effects. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091253

Chicago/Turabian StylePellowski, Jan S., Christian Wiessner, Claudia Buntrock, and Hanna Christiansen. 2025. "Further Validation Study of the Gender-Specific Binary Depression Screening Version (GIDS-15) and Investigation of Intervention Effects" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091253

APA StylePellowski, J. S., Wiessner, C., Buntrock, C., & Christiansen, H. (2025). Further Validation Study of the Gender-Specific Binary Depression Screening Version (GIDS-15) and Investigation of Intervention Effects. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1253. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091253