Using Psychologically Informed Community-Based Participatory Research to Create Culturally Relevant Informal STEM Experiences

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Our Project

3. The Psychological Experiences of Minoritized Youth in STEM

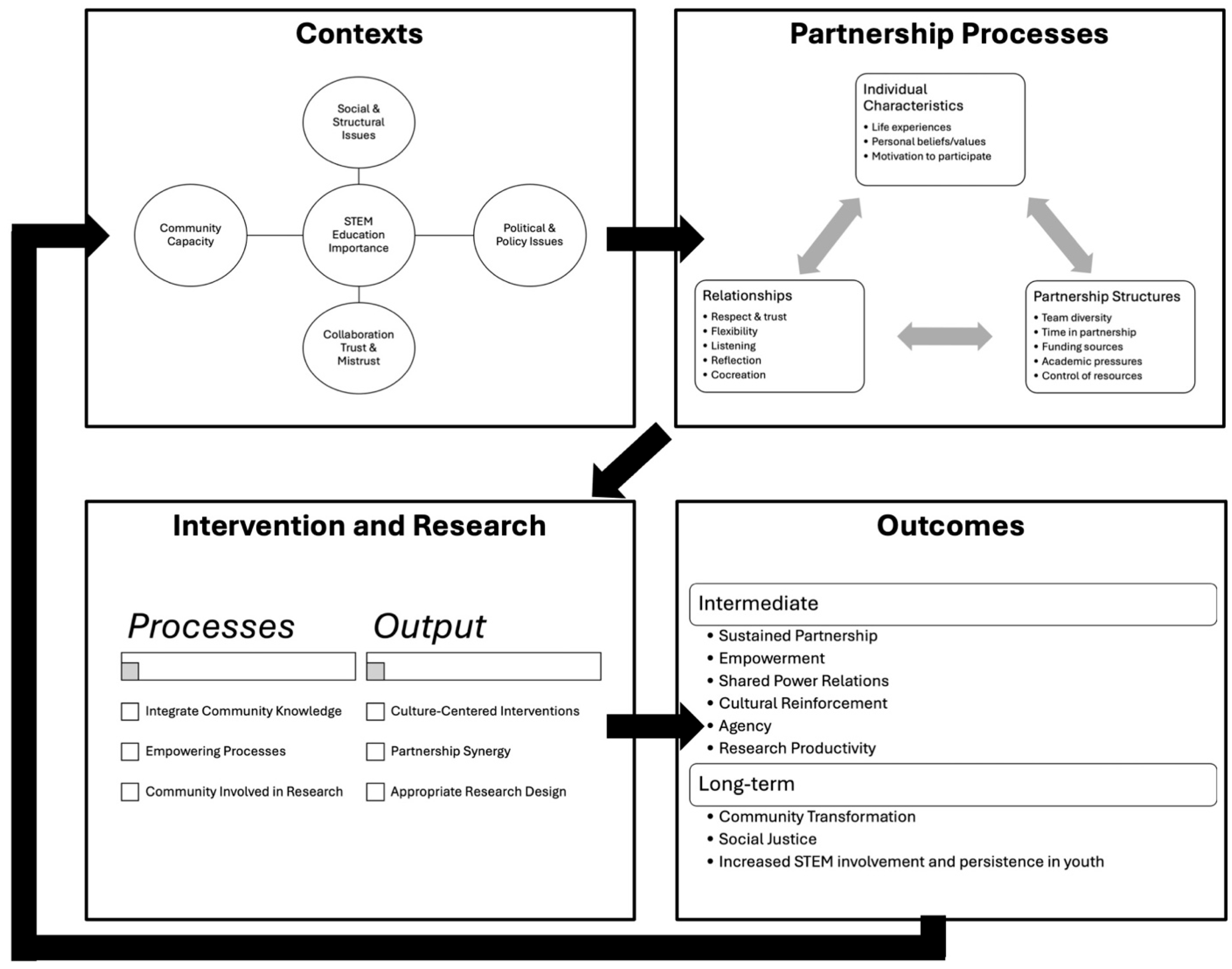

4. Community-Based Participatory Research

5. Informal Science Experiences

6. Cultural Relevance and Responsiveness

7. Our Journey

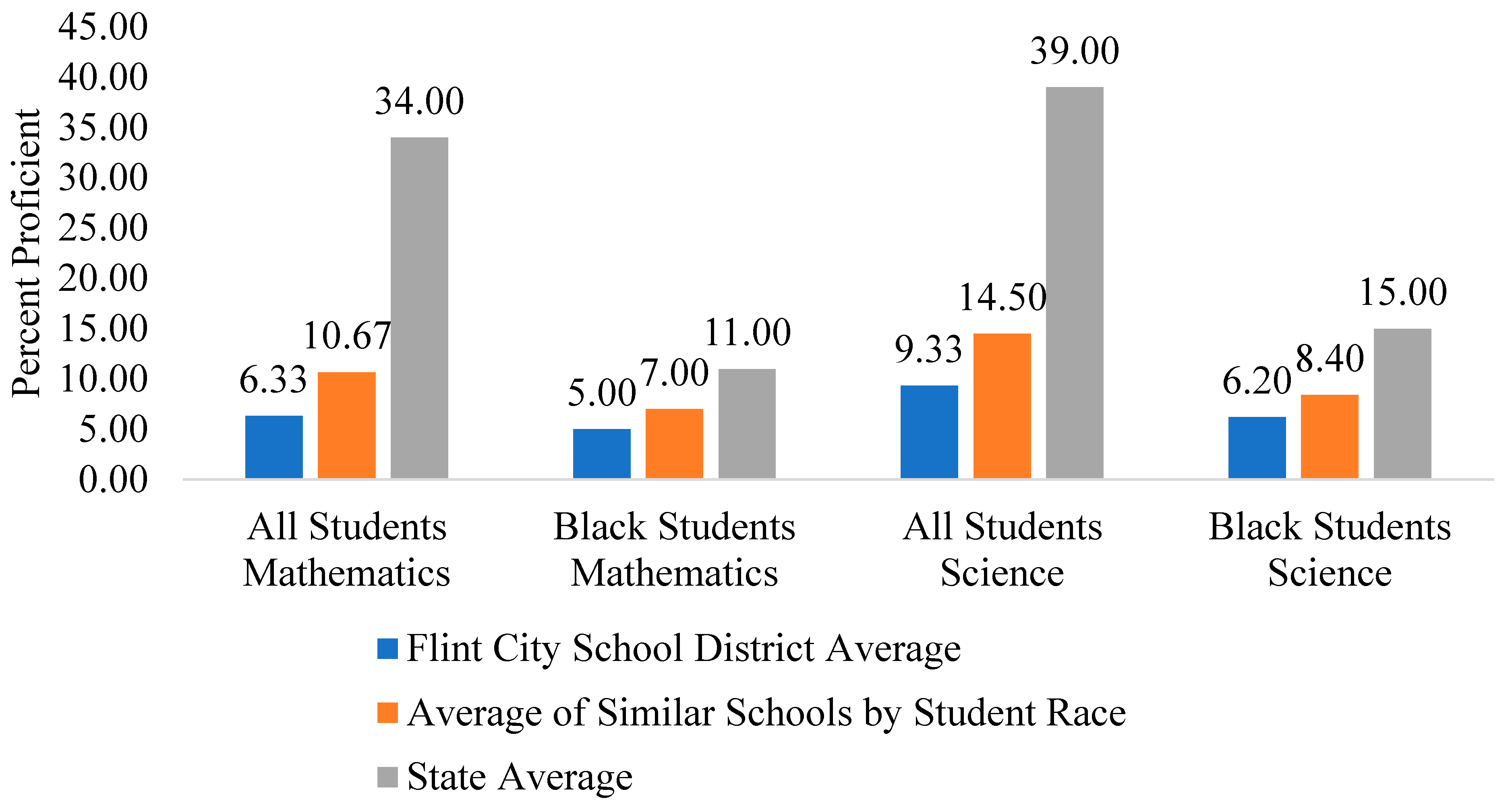

7.1. The Context

7.2. Our Team

7.2.1. University Team Members

7.2.2. Community Team Members

7.3. How Things Started

7.3.1. Conceptualization

“And so many other things like summer camps. I did them for like several days and I saw the excitement that came out of it. I went to what we call deep programs when we go to high schools in the surrounding areas before you used to get like one, two, students, now (…) when I went, we got like seven, eight, ten. So, (…) I feel that we make an impact whatever we do we just by you know by putting the time and effort into it will solve that (…)”

7.3.2. Project Initiation

7.4. How the Project Progressed

“I know you know [what] the concern is, OK. We’re going to give some of the kids you know the skills so they can move out of the community, but frankly, I mean in this day and age, a lot of us do commute, right. So, if you have somebody from Flint, (…) [if] they work somewhere like 20–30 miles away. They have the connection with the community.”

“So, one thing that I see that children struggle with is the influencers that influence the children are mostly people who have things, who have money, and who have jewelry. who have things they’re on the internet, TV, whatever. They’re the influence, so how do I get my children involved in these things? I have to show them a way that they can make money now with technology with STEM. How can that be an actual avenue to show kids (…)”

7.5. Funding

7.6. Waiting

7.6.1. Key Outcomes and Recommendations

7.6.2. Consistent Involvement in Meetings and Community Events

7.7. Consistent and Accessible Communication

7.8. The Importance of Terminology

7.9. Obtaining Funding

7.10. Publishing Practices and Outlets

7.11. Have Realistic Expectations

8. Discussion and Conclusions

8.1. Broader Impacts

8.2. Limitations

8.3. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abelman, R. (2013). On the horns of a dilemma: The institutional vision of church-affiliated HBCUs. Religion & Education, 40(2), 125–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrica, E. J., Lane, T. B., Zobac, S., & Collins, E. (2022). Sense of Belonging and community building within a STEM intervention program: A focus on Latino male undergraduates’ experiences. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 21(2), 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, D. I., Polinsky, N. J., Haden, C. A., & Uttal, D. H. (2021). Whether and how knowledge moderates linkages between parent–child conversations and children’s reflections about tinkering in a children’s museum. Journal of Cognition and Development, 22(2), 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. The Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J., Gomez, K., Lee, U.-S., & Wegemer, C. M. (2024). Embedding racialized selves into the creation of research-practice partnerships. Peabody Journal of Education, 99(3), 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, S., Xu, Y., Washington-Nortey, M., & Chen, C. (2022). Informal STEM learning for young children: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P. J., Chang, R., Gorrall, B. K., Waggenspack, L., Fukuda, E., Little, T. D., & Noam, G. G. (2019). From quality to outcomes: A national study of afterschool STEM programming. International Journal of STEM Education, 6(1), 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenmüller, M. S., Kampschulte, L., Verbeek, L., & Gollwitzer, M. (2023). Science communication gets personal: Ambivalent effects of self-disclosure in science communication on trust in science. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 29(4), 793–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amauchi, J. F., Gauthier, M., Ghezeljeh, A., L. Giatti, L. L., Keats, K., Sholanke, D., Zachari, D., & Gutberlet, J. (2022). The power of community-based participatory research: Ethical and effective ways of researching. Community Development (Columbus, Ohio), 53(1), 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, N., & Dogan, B. (2021). Impact of informal learning environments on STEM education—Views of elementary students and their parents. School Science and Mathematics, 121(6), 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L., DeWitt, J., Osborne, J., Dillon, J., Willis, B., & Wong, B. (2010). “Doing” science versus “being” a scientist: Examining 10/11-year-old schoolchildren’s constructions of science through the lens of identity. Science Education, 94(4), 617–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, J., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, R. L., & Regan de Bere, S. (2018). Optimizing patient and public involvement (PPI): Identifying its “essential” and “desirable” principles using a systematic review and modified Delphi methodology. Health Expectations, 21(1), 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balta-Salvador, R., Olmedo-Torre, N., & Pena, M. (2022). Perceived discrimination and dropout intentions of underrepresented minority students in engineering degrees. IEEE Transactions on Education, 65(3), 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltimore City Public Schools. (2024). City schools at a glance. Available online: https://www.baltimorecityschools.org/o/bcps/page/district-overview (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Bang, M., & Vossoughi, S. (2016). Participatory design research and educational justice: Studying learning and relations within social change making. Cognition and Instruction, 34(3), 173–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquet, C. R., Bromwell, J. L., Hall, M. B., & Frego, J. F. (2013). Rural community–academic partnership model for community engagement and partnered research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 7(3), 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfield, C. (2021). The economic burden of racism from the U.S. education system. National Education Policy Center. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S. T., & Brown, S. G. (2015). Selecting and composing cohesive teams. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belone, L., Lucero, J. E., Duran, B., Tafoya, G., Baker, E. A., Chan, D., Chang, C., Greene-Moton, E., Kelley, M. A., & Wallerstein, N. (2016). Community-based participatory research conceptual model: Community partner consultation and face validity. Qualitative Health Research, 26(1), 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltrán-Grimm, S. (2025). Latina mothers in participatory action research: Insights and reflections of a mathematics co-design session tool. Qualitative Research, 25(1), 263–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J. S. (2019). Fostering relational trust to engage white teachers and researchers on reflections of race, power, and oppression. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez, V. N., Salazar, J., Garcia, L., Ochoa, K. D., Pesch, A., Roldan, W., Soto-Lara, S., Gomez, W., Rodriguez, R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Ahn, J., & Bustamante, A. S. (2023). Designing culturally situated playful environments for early STEM learning with a Latine community. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, B., Calabrese Barton, A., & Garibay, C. (2020). Broadening perspectives on broadening participation: Professional learning tools for more expansive and equitable science communication. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicer, A., Nite, S. B., Capraro, R. M., Barroso, L. R., Capraro, M. M., & Lee, Y. (2017, October 18–21). Moving from STEM to STEAM: The effects of informal STEM learning on students’ creativity and problem-solving skills with 3D printing. 2017 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (pp. 1–6), Indianapolis, IN, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, I. C., Polly, D., Conrad, J., & Algozzine, B. (2016). Student perceptions of a summer ventures in science and mathematics camp experience. School Science and Mathematics, 116(8), 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, K. Z., & Faustin, Y. F. (2022). How community-based participatory research can thrive in virtual spaces: Connecting through photovoice. Human Organization, 81(3), 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonous-Hammarth, M. (2000). Pathways to success: Affirming opportunities for science, mathematics, and engineering majors. The Journal of Negro Education, 69(1/2), 92–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). In other words: Essays toward a reflexive sociology. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. (2000). Pascalian meditations. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, L. (2021). Interdisciplinary research methods: Considering the potential of community-based participatory research in translation. Journal of Translation Studies, 1(1), 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breland-Noble, A., Streets, F. J., & Jordan, A. (2024). Community-based participatory research with Black people and Black scientists: The power and the promise. The Lancet Psychiatry, 11(1), 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, B. A. (2021). Science in the city: Culturally relevant STEM education. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. (2024). Ten years later, flint still doesn’t have clean water. Human Rights Watch. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2024/05/20/ten-years-later-flint-still-doesnt-have-clean-water (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Brown, K. T., & Ostrove, J. M. (2013). What does it mean to be an ally?: The perception of allies from the perspective of people of color: What does it mean to be an ally? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(11), 2211–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, B. L., Mentz, G., Jensen, M., Jacobs, B., Saylor, K. M., Rowe, Z., Israel, B. A., & Lachance, L. (2020). Success in long-standing community-based participatory research (CBPR) partnerships: A scoping literature review. Health Education & Behavior, 47(4), 556–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, B. A., & Johnson, J. T. (2018). Origins of early STEM interest for Black male graduate students in engineering: A community cultural wealth perspective. School Science and Mathematics, 118(6), 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burušić, J., Šimunović, M., & Šakić, M. (2021). Technology-based activities at home and STEM school achievement: The moderating effects of student gender and parental education. Research in Science & Technological Education, 39(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese Barton, A., & Tan, E. (2018). A longitudinal study of equity-oriented STEM-rich making among youth from historically marginalized communities. American Educational Research Journal, 55(4), 761–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, W. B., Reyes, A. G., Rowe, Z., Weinert, J., & Israel, B. A. (2015). Community partner perspectives on benefits, challenges, facilitating factors, and lessons learned from community-based participatory research partnerships in Detroit. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 9(2), 299–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, J. S., Key, K., Bailey, S., Hamm, J. A., Cuthbertson, C. A., Lewis, E. Y., Woolford, S. J., DeLoney, E. H., Greene-Moton, E., Wallace, K., Robinson, D. E., Byers, I., Piechowski, P., Evans, L., McKay, A., Vereen, D., Sparks, A., & Calhoun, K. (2019). Community science as a pathway for resilience in response to a public health crisis in Flint, Michigan. Social Sciences, 8(3), 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, T. J., & Hallar, B. (2018). Taking risks with a growth mindset: Long-term influence of an elementary pre-service after school science practicum. International Journal of Science Education, 40(3), 348–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celedón-Pattichis, S., Borden, L. L., Pape, S. J., Clements, D. H., Peters, S. A., Males, J. R., Chapman, O., & Leonard, J. (2018). Asset-based approaches to equitable mathematics education research and practice. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 49(4), 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J. (2018). Michigan school districts battle widespread teacher shortages. The Detroit News. Available online: https://www.detroitnews.com/story/news/education/2018/09/10/teacher-shortage-michigan-schools/1203975002/ (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Chambers, M. K., Ireland, A., D’Aniello, R., Lipnicki, S., Glick, M., & Tumiel-Berhalter, L. (2015). Lessons learned from the evolution of an academic community partnership: Creating “patient voices”. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 9(2), 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandanabhumma, P. P., Fàbregues, S., Oetzel, J., Duran, B., & Ford, C. (2023). Examining the influence of group diversity on the functioning of community-based participatory research partnerships: A mixed methods study. American Journal of Community Psychology, 71(1–2), 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A., Rodriguez, F. D., Pena, C., Hinojosa, E., Morales, L., Del Bosque, V., Tijerina, Y., & Tarawneh, C. (2020). “Nothing is impossible”: Characteristics of Hispanic females participating in an informal STEM setting. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 15(3), 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheryan, S., Plaut, V. C., Davies, P. G., & Steele, C. M. (2009). Ambient belonging: How stereotypical cues impact gender participation in computer science. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(6), 1045–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidou, D., Papavlasopoulou, S., & Giannakos, M. (2021). Using the lens of science capital to capture and explore children’s attitudes toward science in an informal making-based space. Information and Learning Sciences, 122(5/6), 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G. L., & Garcia, J. (2008). Identity, belonging, and achievement a model, interventions, implications. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(6), 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, K. H. (2018). Confronting color-blind STEM talent development: Toward a contextual model for Black Student STEM identity. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(2), 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S. E., Clifasefi, S. L., Stanton, J., The Leap Advisory Board, Straits, K. J. E., Gil-Kashiwabara, E., Rodriguez Espinosa, P., Nicasio, A. V., Andrasik, M. P., Hawes, S. M., Miller, K. A., Nelson, L. A., Orfaly, V. E., Duran, B. M., & Wallerstein, N. (2018). Community-based participatory research (CBPR): Towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. American Psychologist, 73(7), 884–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisp, G., & Nora, A. (2012). Overview of Hispanics in science, mathematics, engineering and technology (STEM): K-16 representation, preparation and participation. Higher Education Policy for Minorities in the United States. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10919/83076 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Czopp, A. M., Kay, A. C., & Cheryan, S. (2015). Positive stereotypes are pervasive and powerful. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(4), 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daft, R. L., & Lengel, R. H. (1986). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science, 32(5), 554–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, G., Frerichs, L., Jones, J., Kim, M., Schaal, J., Vassar, S., Varma, D., Striley, C., Ruktanonchai, C., Black, A., Hankins, J., Lovelady, N., Cene, C., Green, M., Young, T., Tiwari, S., Cheney, A., Cottler, L., Sullivan, G., … Corbie-Smith, G. (2018). Conceptualizing trust in community-academic research partnerships using concept mapping approach: A multi-CTSA study. Evaluation and Program Planning, 66, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deemer, E. D., Dotterer, A. M., Duhon, S. A., Derosa, P. A., Lim, S., Bowen, J. R., & Howarter, K. B. (2022). Does university context play a role in mitigating threatening race-STEM stereotypes? Test of the stereotype inoculation model. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 17(2), 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaine, D. A. (2021). Characterizing STEM community-based learning through the inter-stakeholder dynamics within a three-tiered model. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 25(2), 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Delaine, D. A., Cardoso, J. R., & Walther, J. (2018). An investigation of inter-stakeholder dynamics supportive of STEM, community-based learning. International Journal of Engineering Education, 35(4), 1094–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. (2022). Flint enters final phase of lead service line replacement. Available online: https://www.michigan.gov/egle/newsroom/press-releases/2022/09/30/flint-enters-final-phase-of-lead-service-line-replacement#:~:text=The%20City%20of%20Flint%20and,program%20and%20water%20system%20infrastructure (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- DeWitt, J., & Archer, L. (2017). Participation in informal science learning experiences: The rich get richer? International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 7(4), 356–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, R., Hazari, Z., Dabney, K., Sonnert, G., & Sadler, P. (2019). Early informal STEM experiences and STEM identity: The importance of talking science. Science Education, 103(3), 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doustmohammadian, A., Mohammadi-Nasrabadi, F., Keshavarz-Mohammadi, N., Hajjar, M., Alibeyk, S., & Hajigholam-Saryazdi, M. (2022). Community-based participatory interventions to improve food security: A systematic review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 1028394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drainoni, M.-L., Walt, G., Martinez, L., Smeltzer, R., Santarpio, S., Munoz-Lopez, R., McClay, C., Keisling, L., Harris, A., Gillen, F., El-Alfi, V., Crable, E., Cogan, A., Carpenter, J., Barkoswki, L., & Battaglia, T. (2023). Coalition building: What happens when external facilitators put CBPR principles in practice? Ethnographic examples from the Massachusetts HEALing Communities study. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 16(1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drazan, J. F., Loya, A. K., Horne, B. D., & Eglash, R. (2017, March 3–4). From sports to science: Using basketball analytics to broaden the appeal of math and science among youth. MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference, Boston, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois, W. E. B., & Eaton, I. (1899). The Philadelphia Negro: A social study (Vol. 14). Publications of the University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Eastis, C. M. (1998). Organizational diversity and the production of social capital. The American Behavioral Scientist (Beverly Hills), 42(1), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (2010). The 95 percent solution: School is not where most Americans learn most of their science. American Scientist, 98(6), 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, J. H., & Meier, D. D. (2021). Expanding the boundaries of informal education programs: An investigation of the role of pre and post-education program experiences and dispositions on youth STEM learning. Frontiers in Education, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, P. J., Stone, L. C., Creary, M. S., Greene-Moton, E., Israel, B. A., Key, K. D., Reyes, A. G., Wallerstein, N., & Schulz, A. J. (2023). Antiracism and community-based participatory research: Synergies, challenges, and opportunities. American Journal of Public Health, 113(1), 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fletcher, F., Hammer, B., & Hibbert, A. (2022). “We know we are doing something good, but what is it?”: The challenge of negotiating between service delivery and research in a CBPR project. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 7(2), 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint & Genesee Economic Alliance. (2025). Industry, employment, and wages [Dataset]. Available online: https://developflintandgenesee.org/data-center/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Gates, H. L., Jr. (2022). The Black Church: This is our story, this is our song. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadiri Khanaposhtani, M., Liu, C. J., Gottesman, B. L., Shepardson, D., & Pijanowski, B. (2018). Evidence that an informal environmental summer camp can contribute to the construction of the conceptual understanding and situational interest of STEM in middle-school youth. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 8(3), 227–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godec, S., Archer, L., & Dawson, E. (2022). Interested but not being served: Mapping young people’s participation in informal STEM education through an equity lens. Research Papers in Education, 37(2), 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guy, B. R., & Feldman, T. (2023). “Please stop bringing up family life, we’re here to talk about science”: Engaging undergraduate women and women of color in STEM through a participatory action research project. Inquiry in Education, 15(1), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Haggler, P. (2018). From the black church basement to the public pavement: Grassroots alliances, the Sunday school, organized youth activism, and a public theology of education. Religious Education, 113(5), 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, M., Key, K., Jefferson, B. L., Muhammud, J., & Johnson, J. E. (2020). Community-based participatory qualitative research for women: Lessons from the Flint Women’s Study. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 14(2), 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C., Dickerson, J., Batts, D., Kauffmann, P., & Bosse, M. (2011). Are we missing opportunities to encourage interest in STEM fields? Journal of Technology Education, 23(1), 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S. R. (2010). An anti-deficit achievement framework for research on students of color in STEM. New Directions for Institutional Research, 2010(148), 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, C., Erete, S., & Piper, A. M. (2019). Deconstructing community-based collaborative design: Towards more equitable participatory design engagements. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Matias, L., Pérez-Donato, L., Román, P. L., Laureano-Torres, F., Calzada-Jorge, N., Mendoza, S., Washington, A. V., & Borrero, M. (2020). An exploratory study comparing students’ science identity perceptions derived from a hands-on research and nonresearch-based summer learning experience. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 48(2), 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, S., Duran, B., Wallerstein, N., Avila, M., Belone, L., Lucero, J., Magarati, M., Mainer, E., Martin, D., Muhammad, M., Oetzel, J., Pearson, C., Sahota, P., Simonds, V., Sussman, A., Tafoya, G., & Hat, E. W. (2012). Evaluating community-based participatory research to improve community-partnered science and community health. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 6(3), 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hightower, A. (2015). Demolition means progress. The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, A. J., McGuire, L., Rutland, A., Hartstone-Rose, A., Irvin, M. J., Winterbottom, M., Balkwill, F., Fields, G. E., & Mulvey, K. L. (2021). The relations and role of social competencies and belonging with math and science interest and efficacy for adolescents in informal STEM programs. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(2), 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohl, S. D., Neuhouser, M. L., & Thompson, B. (2022). Re-orienting transdisciplinary research and community-based participatory research for health equity. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 6(1), e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horns, J. J., Nadkarni, N., & Anholt, A. (2020). How repeated exposure to informal science education affects content knowledge of and perspectives on science among incarcerated adults. PLoS ONE, 15(5), e0233083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsford, S. D. (2010). Black superintendents on educating Black students in separate and unequal contexts. The Urban Review, 42(1), 58–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, I. M. (2022). God, grades, and graduation: Religion’s surprising impact on academic success. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B. A., Krieger, J., Vlahov, D., Ciske, S., Foley, M., Fortin, P., Guzman, J. R., Lichtenstein, R., McGranaghan, R., Palermo, A.-G., & Tang, G. (2006). Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: Lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle urban research centers. Journal of Urban Health, 83(6), 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, B. A., Schulz, A. J., Parker, E. A., & Becker, A. B. (1998). Review of community-based research: Assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19, 173–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquez, F., Vaughn, L., Boards, A., Wells, J., & Maynard, K. (2020). Creating a culture of youth as co-researchers: The kickoff of a year-long stem pipeline program. Journal of STEM Outreach, 3(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagosh, J., Bush, P. L., Salsberg, J., Macaulay, A. C., Greenhalgh, T., Wong, G., Cargo, M., Green, L. W., Herbert, C. P., & Pluye, P. (2015). A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, M., Daugherty, R., Garibay, C., Sanford, C., Koerner, J., Lewin, J., & Braun, R. (2016). Bridging in-school and out-of-school STEM learning through a collaborative, community-based after-school program. Connected Science Learning, 1(1), 12420447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, K. D., Furr-Holden, D., Lewis, E. Y., Cunningham, R., Zimmerman, M. A., Johnson-Lawrence, V., & Selig, S. (2019). The continuum of community engagement in research: A roadmap for understanding and assessing progress. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 13(4), 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, T. A., & Kaiser, C. R. (2020). Person-message fit: Racial identification moderates the benefits of multicultural and colorblind diversity approaches. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(6), 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X., Dabney, K. P., & Tai, R. H. (2014). The association between science summer camps and career interest in science and engineering. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 4(1), 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kricorian, K., Seu, M., Lopez, D., Ureta, E., & Equils, O. (2020). Factors influencing participation of underrepresented students in STEM fields: Matched mentors and mindsets. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchynka, S. L., Reifsteck, T. V., Gates, A. E., & Rivera, L. M. (2022). Which STEM relationships promote science identities, attitudes, and social belonging? A longitudinal investigation with high school students from underrepresented groups. Social Psychology of Education, 25(4), 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H. (2017). Effects of 3D printing and design software on students’ interests, motivation, mathematical and technical skills. Journal of STEM Education, 18(4). Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/181996 (accessed on 3 November 2023).

- LaCosse, J., Murphy, M. C., Garcia, J. A., & Zirkel, S. (2020). The role of STEM professors’ mindset beliefs on students’ anticipated psychological experiences and course interest. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(5), 949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2021a). Culturally relevant pedagogy: Asking a different question. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2021b). Three decades of culturally relevant, responsive, & sustaining pedagogy: What lies ahead? The Educational Forum, 85(4), 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2022). The dreamkeepers: Successful teachers of African American children (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Lawner, E. K., Quinn, D. M., Camacho, G., Johnson, B. T., & Pan-Weisz, B. (2019). Ingroup role models and underrepresented students’ performance and interest in STEM: A meta-analysis of lab and field studies. Social Psychology of Education, 22(5), 1169–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Clark, J. K., Schmiesing, R., Kaiser, M. L., Reece, J., & Park, S. (2024). Perspectives of community members on community-based participatory research: A systematic literature review. Journal of Urban Affairs, 47(8), 2916–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Mazmanian, M., & Perlow, L. (2020). Fostering positive relational dynamics: The power of spaces and interaction scripts. Academy of Management Journal, 63(1), 96–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J., Barnes-Johnson, J., & Evans, B. R. (2019). Using computer simulations and culturally responsive instruction to broaden urban students’ participation in STEM. Digital Experiences in Mathematics Education, 5(2), 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, L., Ronis, S., Cowper-Smith, Y., & Vaccarino, O. (2019). A scoping review: The utility of participatory research approaches in psychology. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(8), 1865–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, E. C., & Mamiya, L. H. (1990). The Black Church in the African American experience. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, J. S., Lee, W. C., & Hawkins Ash, C. D. (2021). Potential engineers: A systematic literature review exploring Black children’s access to and experiences with STEM. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(4), 1003–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, K. W., & Ford-Paz, R. (2013). Early career academic researchers and community-based participatory research: Wrestling match or dancing partners? Clinical and Translational Science, 6(6), 490–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero, J. E., Boursaw, B., Eder, M. M., Greene-Moton, E., Wallerstein, N., & Oetzel, J. G. (2020). Engage for equity: The role of trust and synergy in community-based participatory research. Health Education & Behavior, 47(3), 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltese, A. V., & Cooper, C. S. (2017). STEM pathways: Do men and women differ in why they enter and exit? AERA Open, 3(3), 2332858417727276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J. (2008). Stuck in the shallow end: Education, race, and computing (1st ed.). MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mau, W. J., & Li, J. (2018). Factors influencing STEM career aspirations of underrepresented high school students. The Career Development Quarterly, 66(3), 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayan, M., Lo, S., Richter, S., Dastjerdi, M., & Drummond, J. (2016). Community-based participatory research: Ameliorating conflict when community and research practices meet. Progress in Community Health Partnerships, 10(2), 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCray, C. R., Grant, C. M., & Beachum, F. D. (2010). Pedagogy of self-development: The role the Black church can have on African American students. The Journal of Negro Education, 79(3), 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- McCuistian, C., Peteet, B., Burlew, K., & Jacquez, F. (2023). Sexual health interventions for racial/ethnic minorities using community-based participatory research: A systematic review. Health Education & Behavior, 50(1), 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, S. J., Occa, A., Peng, W., Awonuga, O., & Morgan, S. E. (2022). Community-based participatory research (CBPR) to enhance participation of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials: A 10-year systematic review. Health Communication, 37(9), 1075–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntosh, R., & Curry, K. (2020). The role of a Black Church–school partnership in supporting the educational achievement of African American students. The School Community Journal, 30(1), 161–189. [Google Scholar]

- McMahon, S. D., & Wernsman, J. (2009). The relation of classroom environment and school belonging to academic self-efficacy among urban fourth- and fifth-grade students. The Elementary School Journal, 109(3), 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McShane, S. L., & Von Glinow, M. A. (2003). Organizational behavior: Emerging realities for the workplace revolution (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Michigan Center for Educational Performance and Information. (2024a). Grades 3–8 state testing (includes PSAT data) performance [Dataset]. Available online: https://mischooldata.org/grades-3-8-state-testing-includes-psat-data-proficiency/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Michigan Center for Educational Performance and Information. (2024b). Graduation/dropout rates [Dataset]. Available online: https://www.mischooldata.org/graddropout-rate/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Michigan Center for Educational Performance and Information. (2024c). High school state testing performance [Dataset]. Available online: https://www.mischooldata.org/high-school-state-testing-performance/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Michigan Center for Educational Performance and Information. (2024d). Newly hired teachers: Retention rates after five years of employment [Michigan’s Education Staff]. Available online: https://www.mischooldata.org/michigans-education-staff/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Michigan Center for Educational Performance and Information. (2024e). Teacher retention by school poverty status [Michigan’s Education Staff]. Available online: https://www.mischooldata.org/michigans-education-staff/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Michigan Department of Technology, Management, & Budget. (2025). Employment projections for industry sectors 2022–2032. Michigan Labor Market Information. Available online: https://www.milmi.org/DataSearch/Employment-Projections (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Mikesell, L., Bromley, E., & Khodyakov, D. (2013). Ethical community-engaged research: A literature review. American Journal of Public Health, 103(12), e7–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minkler, M., & Wallerstein, N. (2008). Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/umichigan/detail.action?docID=588918 (accessed on 29 July 2024).

- Mirra, N., & Rogers, J. (2016). Institutional participation and social transformation: Considering the goals and tensions of university-initiated YPAR projects with K-12 youth. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(10), 1255–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, L. (2012). Parental involvement in early childhood care education: A study. International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, 2(2), 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr-Schroeder, M. J., Jackson, C., Miller, M., Walcott, B., Little, D. L., Speler, L., Schooler, W., & Schroeder, D. C. (2014). Developing middle school students’ interests in STEM via summer learning experiences: See Blue STEM Camp. School Science and Mathematics, 114(6), 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montañez, S. R. (2023). Advancing equity through research: The importance of asset-based approaches and methods. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 86, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore de Peralta, A., Smithwick, J., & Torres, M. E. (2020). Perceptions and determinants of partnership trust in the context of Community-Based Participatory Research. Participatory Research, 13(1), 67–95. [Google Scholar]

- Moote, J., Archer, L., DeWitt, J., & MacLeod, E. (2020). Science capital or STEM capital? Exploring relationships between science capital and technology, engineering, and maths aspirations and attitudes among young people aged 17/18. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(8), 1228–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morckel, V., & Terzano, K. (2018). Legacy city residents’ lack of trust in their governments: An examination of Flint, Michigan residents’ trust at the height of the water crisis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 41, 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, M., Wallerstein, N., Sussman, A. L., Avila, M., Belone, L., & Duran, B. (2015). Reflections on researcher identity and power: The impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Critical Sociology, 41(7–8), 1045–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M. C., Kroeper, K. M., & Ozier, E. M. (2018). Prejudiced places: How contexts shape inequality and how policy can change them. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 5(1), 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M. C., Walton, G. M., Stangor, C., & Crandall, C. S. (2013). From prejudiced people to prejudiced places: A social-contextual approach to prejudice (1st ed., pp. 181–203). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mwangi, C. A. G., Bettencourt, G. M., Wells, R. S., Dunton, S. T., Kimball, E. W., Pachucki, M. C., Dasgupta, N., & Thoma, H. S. (2023). Demystifying the magic: Investigating the success of university-community partnerships for broadening participation in STEM. Journal of Women and Minorities in Science and Engineering, 29(1), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, P. N., Muriithi, C. M., & Agufana, P. B. (2022). Exploring the benefits of educational robots in STEM learning: A systematic review. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 11(6), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, J. M., & Hansen, A. K. (2021). Perspectives on community STEM: Learning from partnerships between scientists, researchers, and youth. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 61(3), 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Science Foundation. (2024). Award report. NSF by the Numbers. Available online: https://tableau.external.nsf.gov/views/NSFbyNumbers/Details?%3AisGuestRedirectFromVizportal=y&%3Aembed=y&%3Alinktarget=_blank&%3Atoolbar=top (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- Navickis-Brasch, A., Kern, A., Fiedler, F., Cadwell, J., Laumatia, L., Haynie, K., & Meyer, C. (2014, June 15–18). Restoring water, culture, and relationships: Using a community-based participatory research methodology for engineering education. 2014 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings, Indianapolis, IN, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, K. J., Leonard, J., Buss, A., Wright, C. G., & Barnes-Johnson, J. (2020). Informal STEM: Learning with robotics and game design in an urban context. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(2), 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, U., & Riegle-Crumb, C. (2021). Who is a scientist? The relationship between counter-stereotypical beliefs about scientists and the STEM major intentions of Black and Latinx male and female students. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaisen, L. B., Ulriksen, L., & Holmegaard, H. T. (2023). Why science education and for whom? The contributions of science capital and Bildung. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 13(3), 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochocka, J., Janzen, R., Nelson, G., Rutman, I. D., & Anthony, W. A. (2002). Sharing power and knowledge: Professional and mental health consumer/survivor researchers working together in a participatory action research project. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(4), 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office for Civil Rights. (2017). Educational equity report for Flint school district. National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://ocrdata.ed.gov/profile/us/mi/flint_school_district_of_the_city_of?surveyYear=2020&nces=2614520 (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- O’Leary, J. T., Zewde, S., Mankoff, J., & Rosner, D. K. (2019, May 4–9). Who gets to future? Race, representation, and design methods in Africatown. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–13), New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, N. A., Morton, T. R., Miles, M. L., & Roby, R. S. (2020). What about us? Exploring the challenges and sources of support influencing Black students’ STEM identity development in postsecondary education. The Journal of Negro Education, 88(3), 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrove, J. M., & Brown, K. T. (2018). Are allies who we think they are?: A comparative analysis. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(4), 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. W., Vani, P., Saint-Hilaire, S., & Kraus, M. W. (2022). Disadvantaged group activists’ attitudes toward advantaged group allies in social movements. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 98, 104226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, A., Ochoa, K. D., Fletcher, K. K., Bermudez, V. N., Todaro, R. D., Salazar, J., Gibbs, H. M., Ahn, J., Bustamante, A. S., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2022). Reinventing the public square and early educational settings through culturally informed, community co-design: Playful learning landscapes. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 933320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (1st ed.). Oxford University Press, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Pinkard, N., Erete, S., Caitlin, M., Majors, Y., & Walker, N. (2025). Increasing STEM engagement through opportunity landscaping. Acta Psychologica, 253, 104705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittsburhg Public Schools. (2024). Pennsylvania value added assessment system (PVAAS) dashboard. Available online: https://resources.finalsite.net/images/v1721323563/pghschoolsorg/jtyojk2wd4rl6m5xoypy/2017districtperformanceresults.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Pivik, J. R., & Goelman, H. (2011). Evaluation of a community-based participatory research consortium from the perspective of academics and community service providers focused on child health and well-being. Health Education & Behavior, 38(3), 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plummer, J. D., & Small, K. J. (2018). Using a planetarium fieldtrip to engage young children in three-dimensional learning through representations, patterns, and lunar phenomena. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 8(3), 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocock, T., Smith, M., & Wiles, J. (2021). Recommendations for virtual qualitative health research during a pandemic. Qualitative Health Research, 31(13), 2403–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, R. J., MacDonald, S., Leech, J., Brumfield, J., Ellis, M., Smith, L., & Shaeffer, J. (2010, April 18–20). Techfacturing: A summer day camp designed to promote STEM interest in middle school students through exposure to local manufacturing facilities. 2010 ASEE Southeast Section Conference, Blacksburg, VA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Quirke, S., & Hossain, S. (2023). Evaluation of the development of science capital in an informal science learning setting [Preprint]. In Review. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattan, A., Good, C., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). “It’s ok—Not everyone can be good at math”: Instructors with an entity theory comfort (and demotivate) students. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(3), 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, F., Talib, O., Manaf, U. K. A., & Hassan, S. A. (2018). Students Attitude towards science, technology, engineering and mathematics in developing career aspiration. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 8(5), 962–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, R., Schlesinger, M., & Lesnick, J. (2023). The school district of Philadelphia PSSA performance trends: 2014-15 to 2021-22 [Research Brief]. Available online: https://www.philasd.org/research/wp-content/uploads/sites/90/2023/03/PSSA-2021-22-Trends-Brief-January-2023.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2024).

- Roberts, J. K., Pavlakis, A. E., & Richards, M. P. (2021). It’s more complicated than it seems: Virtual qualitative research in the COVID-19 era. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 16094069211002959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Espinosa, P., & Verney, S. P. (2021). The underutilization of community-based participatory research in psychology: A systematic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumala, B. B., Hidary, J., Ewool, L., Emdin, C., & Scovell, T. (2011). Tailoring science outreach through e-matching using a community-based participatory approach. PLoS Biology, 9(3), e1001026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, K., Eilam, E., Bigger, S. W., & Barry, F. (2018). University-led STEM outreach programs: Purposes, impacts, stakeholder needs and institutional support at nine Australian universities. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 586–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J., Seccia, I. T., Maldonado, J. V., Hernandez, L., Bermudez, V. N., Acevedo-Farag, L. M., Ahn, J., & Bustamante, A. S. (2025). Sustaining Latine families’ cultural values through technology mediation practices. Journal of Latinos and Education, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, V., Sanchez-Youngman, S., Dickson, E., Burgess, E., Haozous, E., Trickett, E., Baker, E., & Wallerstein, N. (2021). CBPR implementation framework for community-academic partnerships. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(3–4), 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scher, B. D., Scott-Barrett, J., Hickman, M., & Chrisinger, B. W. (2023). Participatory research emergent recommendations for researchers and academic institutions: A rapid scoping review. Journal of Participatory Research Methods, 4(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholarships 360. (2024). Top 36 christian scholarships in June 2024. Available online: https://scholarships360.org/scholarships/christian-scholarships/ (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Scott, K. A., & White, M. A. (2013). COMPUGIRLS’ standpoint: Culturally responsive computing and its effect on girls of color. Urban Education, 48(5), 657–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E., Shen, Y., & Alfaro, E. C. (2019). Adolescents’ beliefs about math ability and their relations to STEM career attainment: Joint consideration of race/ethnicity and gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(2), 306–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siciliano, P., Hornbeck, B., Hanks, S., Kuhn, S., Zbehlik, A., & Chester, A. L. (2018). Taking a look at the health sciences and technology academy (HSTA): Student-research partnership increases survey size, hands-on STEM learning, and research-community connections. Journal of STEM Outreach, 1(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simanullang, F., Roem, E. R., & Arif, E. (2024). Cross-cultural communication and organizational culture in forming organizational cohesiveness. Riwayat: Educational Journal of History and Humanities, 7(1), 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, J. S., & Parsons, E. C. (2009). African American perspectives and informal science educational experiences. Science Education, 93(2), 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skipper, Y., & Pepler, D. J. (2021). Knowledge mobilization: Stepping into interdependent and relational space using co-creation. Action Research, 19(3), 588–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S. (2021). Closeness and other affiliative outcomes generated from the Fast Friends procedure: A comparison with a small-talk task and unstructured self-disclosure and the moderating role of mode of communication. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(5), 1452–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprecher, S., Treger, S., Wondra, J. D., Hilaire, N., & Wallpe, K. (2013). Taking turns: Reciprocal self-disclosure promotes liking in initial interactions. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(5), 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanich, C. A., Pelch, M. A., Theobald, E. J., & Freeman, S. (2018). A new approach to supplementary instruction narrows achievement and affect gaps for underrepresented minorities, first-generation students, and women. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 19(3), 846–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, C. R., Tulagan, N., & Simpkins, S. D. (2022). Black and Latinx adolescents’ STEM motivational beliefs: A systematic review of the literature on parent STEM support. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 1877–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. M., Spencer, S. J., & Aronson, J. (2002). Contending with group image: The psychology of stereotype and social identity threat. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 34, 379–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, S., Andrade, R., & Page, M. (2016). Motivating young Native American students to pursue STEM learning through a culturally relevant science program. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 25(6), 947–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suarez-Balcazar, Y. (2020). Meaningful engagement in research: Community residents as co-creators of knowledge. American Journal of Community Psychology, 65(3–4), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šimunović, M., & Babarović, T. (2020). The role of parents’ beliefs in students’ motivation, achievement, and choices in the STEM domain: A review and directions for future research. Social Psychology of Education, 23(3), 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, E., & Calabrese Barton, A. (2018). Towards critical justice: Exploring intersectionality in community-based STEM-rich making with youth from non-dominant communities. Equity & Excellence in Education, 51(1), 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, S., & Kennedy, H. (2022). Social work and youth participatory action research (YPAR): Past, present, and future. Social Work, 67(3), 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Hundred-Seven. (2024). HBCU listing. Available online: https://www.thehundred-seven.org/hbculist.html (accessed on 26 August 2024).

- The Social Capital Institute. (2023). Guide to social capital: The concept, theory, and its research. Available online: https://www.socialcapitalresearch.com/guide-to-social-capital-the-concept-theory-and-its-research/ (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Thompson, J. D., & Jesiek, B. K. (2017). Transactional, cooperative, and communal: Relating the structure of engineering engagement programs with the nature of partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 23(2), 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. J. (2012). The politics of inequality a political history of the idea of economic inequality in America. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, V. N., Williams, E. C., Ceballos, R. M., Donovan, D. M., Duran, B., & Ornelas, I. J. (2020). Participant engagement in a community based participatory research study to reduce alcohol use among Latino immigrant men. Health Education Research, 35(6), 627–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A. C., Zarin, W., Rios, P., Nincic, V., Khan, P. A., Ghassemi, M., Diaz, S., Pham, B., Straus, S. E., & Langlois, E. V. (2018). Engaging policy-makers, health system managers, and policy analysts in the knowledge synthesis process: A scoping review. Implementation Science, 13(1), 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Government Accountability Office. (2016). K-12 education: Better use of information could help agencies identity disparities and address racial discrimination. (No. Report to Congressional Requesters). Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-16-345.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- United States Government Accountability Office. (2022). K-12 education: Student Population has significantly diversified, but many schools remain divided along racial, ethnic, and economic lines. (No. Report to the Chairman, Committee on Education and Labor). House of Representatives. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104737.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2023).

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). U.S. census quick facts (2017–2021). Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/flintcitymichigan (accessed on 2 July 2024).

- Üçgül, M., & Altıok, S. (2022). You are an astroneer: The effects of robotics camps on secondary school students’ perceptions and attitudes towards STEM. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 32(3), 1679–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakil, S., & Ayers, R. (2019). The racial politics of STEM education in the USA: Interrogations and explorations. Race Ethnicity and Education, 22(4), 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, E. S., & Gubrium, A. (2020). Shifting to virtual CBPR protocols in the time of Corona Virus/COVID-19. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920977315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, L. M., Jacquez, F., Lindquist-Grantz, R., Parsons, A., & Melink, K. (2017). Immigrants as research partners: A review of immigrants in community-based participatory research (CBPR). Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(6), 1457–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, K. N., Pedersen, R. M., & Baucum, M. N. (2020). Improving perceptions of STEM careers through informal learning environments. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 13(1), 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorauer, J. D., & Petsnik, C. (2023). The disempowering implications for members of marginalized groups of imposing a focus on personal experiences in discussions of intergroup issues. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125(1), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walan, S., & Gericke, N. (2021). Factors from informal learning contributing to the children’s interest in STEM—Experiences from the out-of-school activity called children’s university. Research in Science & Technological Education, 39(2), 185–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, N., Oetzel, J., Duran, B., Tafoya, G., Belone, L., & Rae, R. (2008). What predicts outcomes in CBPR? In Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed., pp. 371–392). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wine, O., Ambrose, S., Campbell, S., Villeneuve, P. J., Burns, K. K., & Vargas, A. O. (2017). Key components of collaborative research in the context of environmental health: A scoping review. Journal of Research Practice, 13(2), R2. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C., & Lastrapes, R. E. (2021). Impact of STEM sense of belonging on career interest: The role of STEM attitudes. Journal of Career Development, 49(6), 1215–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M. (2021). Neighborhood structural characteristics, perceived neighborhood environment, and problem behaviors among at-risk adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(7), 2639–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. R., Ortiz, N., & Young, J. L. (2016). STEMulating interest: A meta-analysis of the effects of out-of-school time on student STEM interest. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 5(1), 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. R., Young, J., & Witherspoon, T. (2019). Informing informal STEM learning: Implications for mathematics identity in African American students. Journal of Mathematics Education, 12(1), 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MSTEP Math | MSTEP Science | PSAT Math | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Number of Students | Number of Black Students | Number of Economically Disadvantaged Black Students | Percentage of All Students Not Proficient | Percentage of Black Students Not Proficient | Percentage of All Students Not Proficient | Percentage of Black Students Not Proficient | Percentage of All Students Not Proficient | Percentage of Black Students Not Proficient |

| 3rd | 222 | 148 | 142 | 81.10% | 83.11% | - | - | - | - |

| 4th | 263 | 172 | 163 | 77.57% | 84.88% | - | - | - | - |

| 5th | 264 | 175 | 165 | 82.20% | 86.86% | 62.50% | 69.14% | - | - |

| 6th | 202 | 151 | 140 | 80.20% | 83.44% | - | - | - | - |

| 7th | 133 | 103 | 96 | 96.24% | 84.68% | - | - | - | - |

| 8th | 172 | 126 | 119 | - | - | 71.51% | 80.16% | 88.95% | 93.65% |

| 11th | 163 | 133 | 115 | - | - | 53.99% | 57.14% | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

LaCosse, J.; Donaldson, E.S.; Ferreira, T.; Burzo, M. Using Psychologically Informed Community-Based Participatory Research to Create Culturally Relevant Informal STEM Experiences. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091249

LaCosse J, Donaldson ES, Ferreira T, Burzo M. Using Psychologically Informed Community-Based Participatory Research to Create Culturally Relevant Informal STEM Experiences. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091249

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaCosse, Jennifer, E. Shirl Donaldson, Thiago Ferreira, and Mihai Burzo. 2025. "Using Psychologically Informed Community-Based Participatory Research to Create Culturally Relevant Informal STEM Experiences" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091249

APA StyleLaCosse, J., Donaldson, E. S., Ferreira, T., & Burzo, M. (2025). Using Psychologically Informed Community-Based Participatory Research to Create Culturally Relevant Informal STEM Experiences. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1249. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091249