General Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of Physical Activity’s Impact on Well-Being Among Norwegian Adolescents: A Gender and Age Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Data Collection, and Sample

2.2. Ethics

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Subjective Well-Being

2.3.2. Physical Activity

2.3.3. General Self-Efficacy

2.3.4. Moderator and Control Variables

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Correlation Results

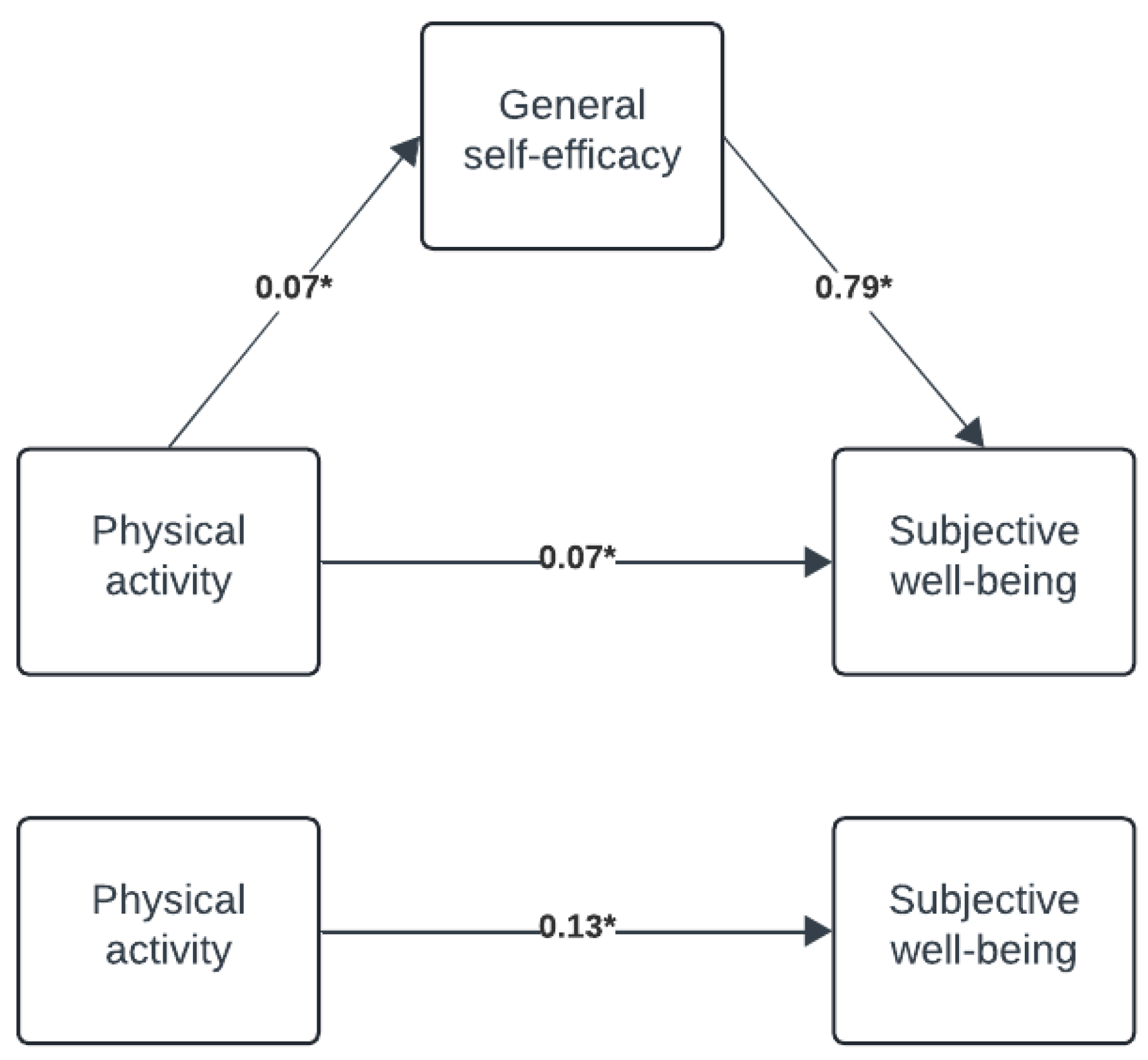

3.3. Mediation Analysis (Aim 1)

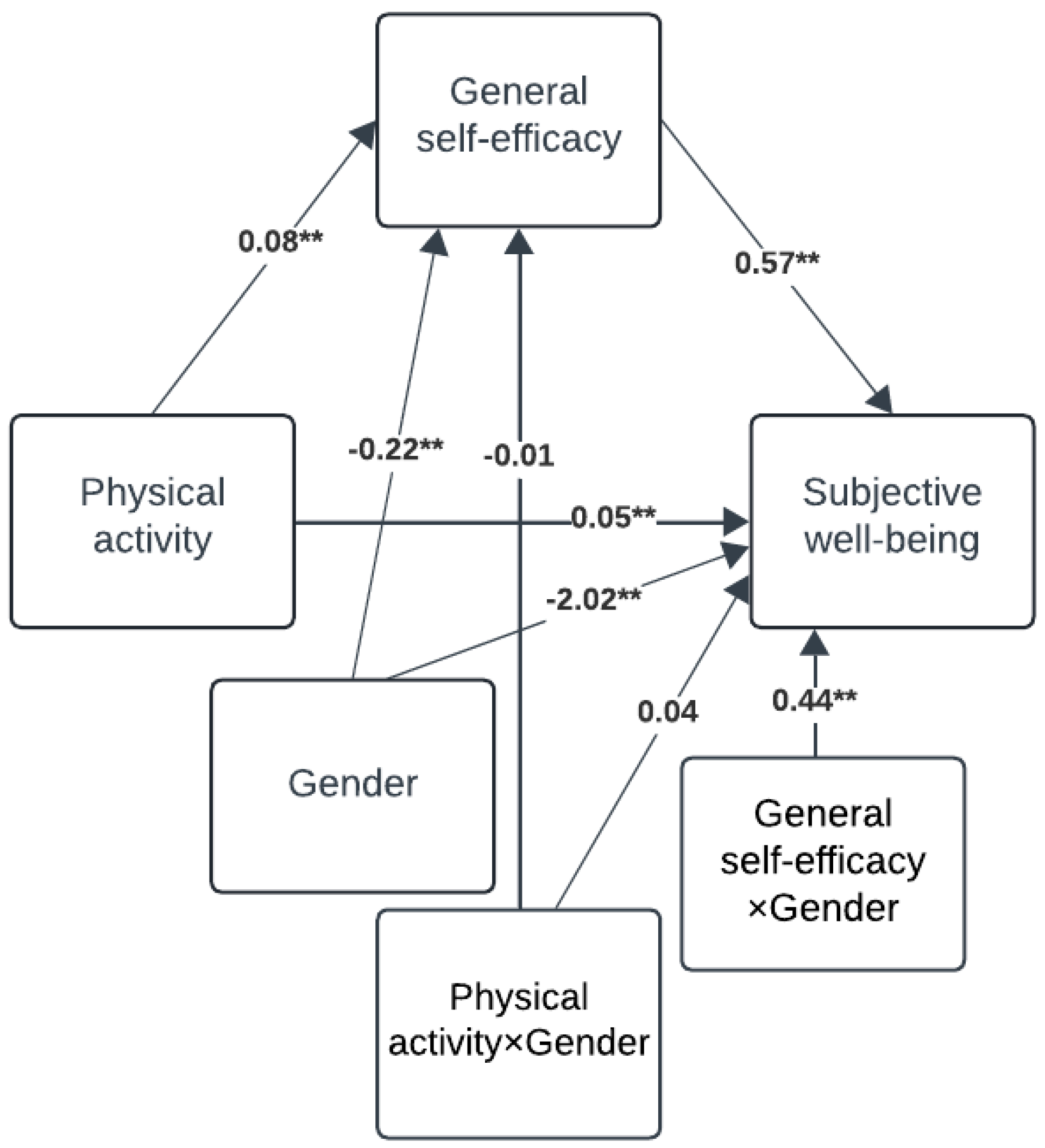

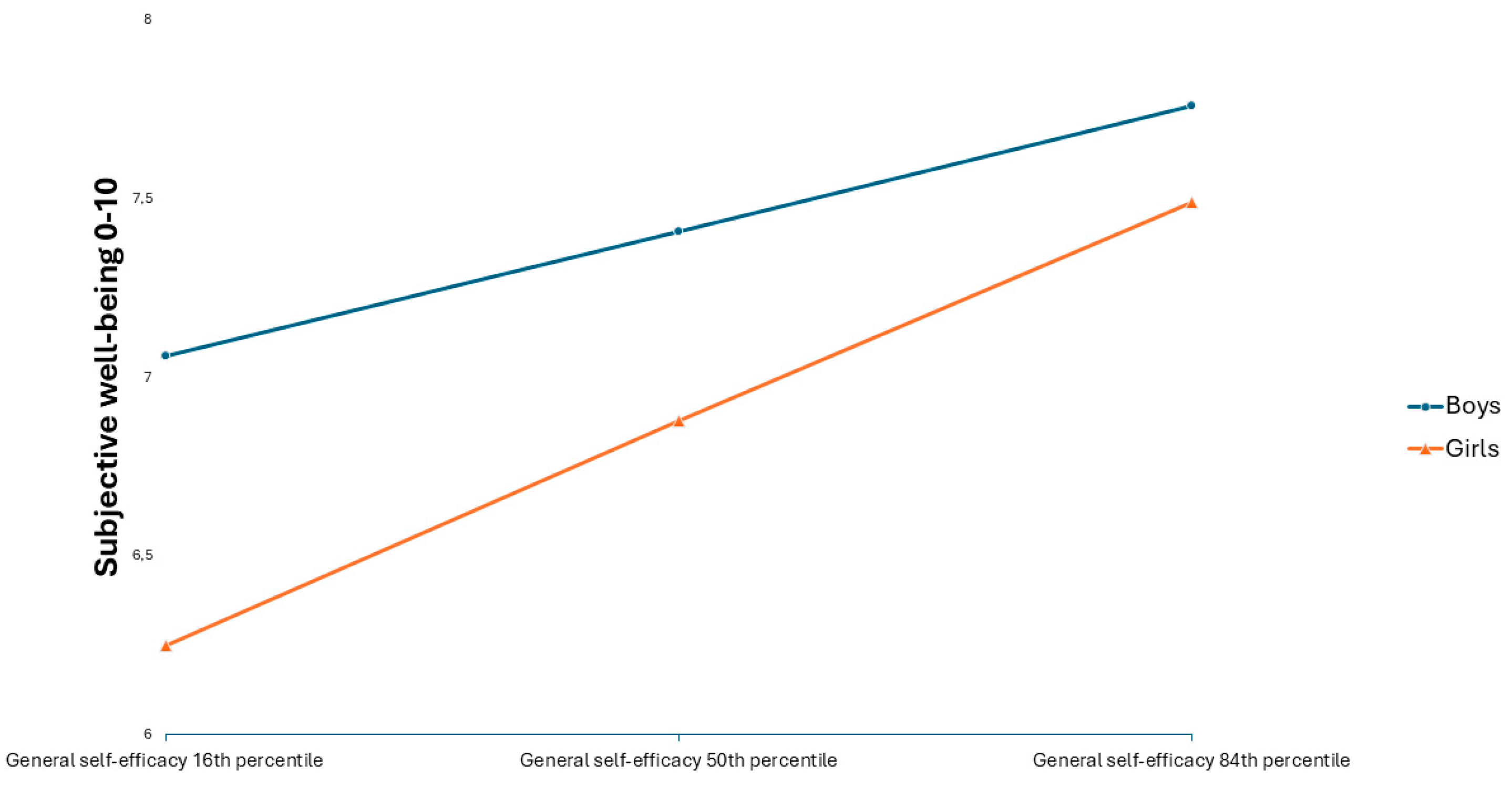

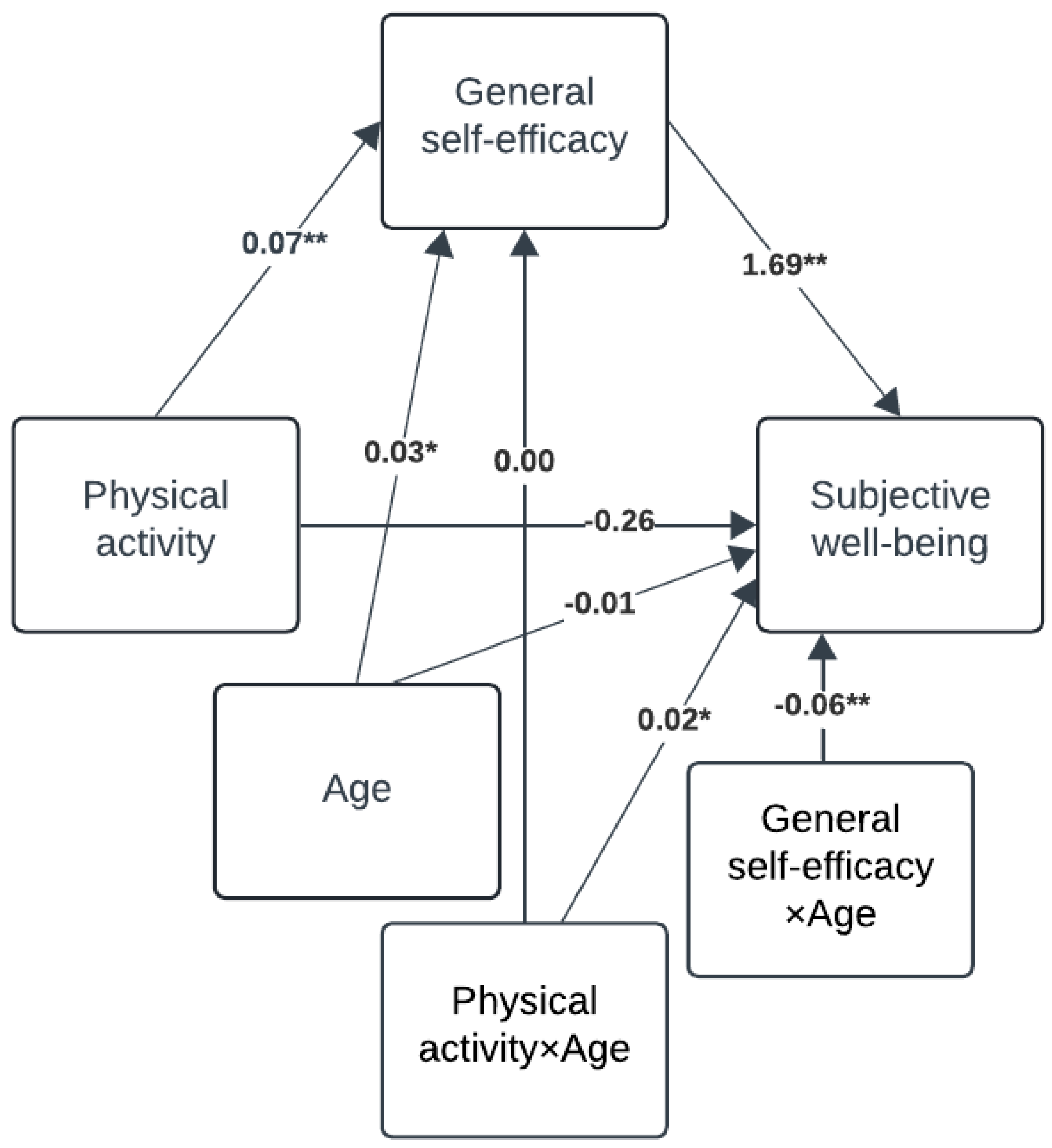

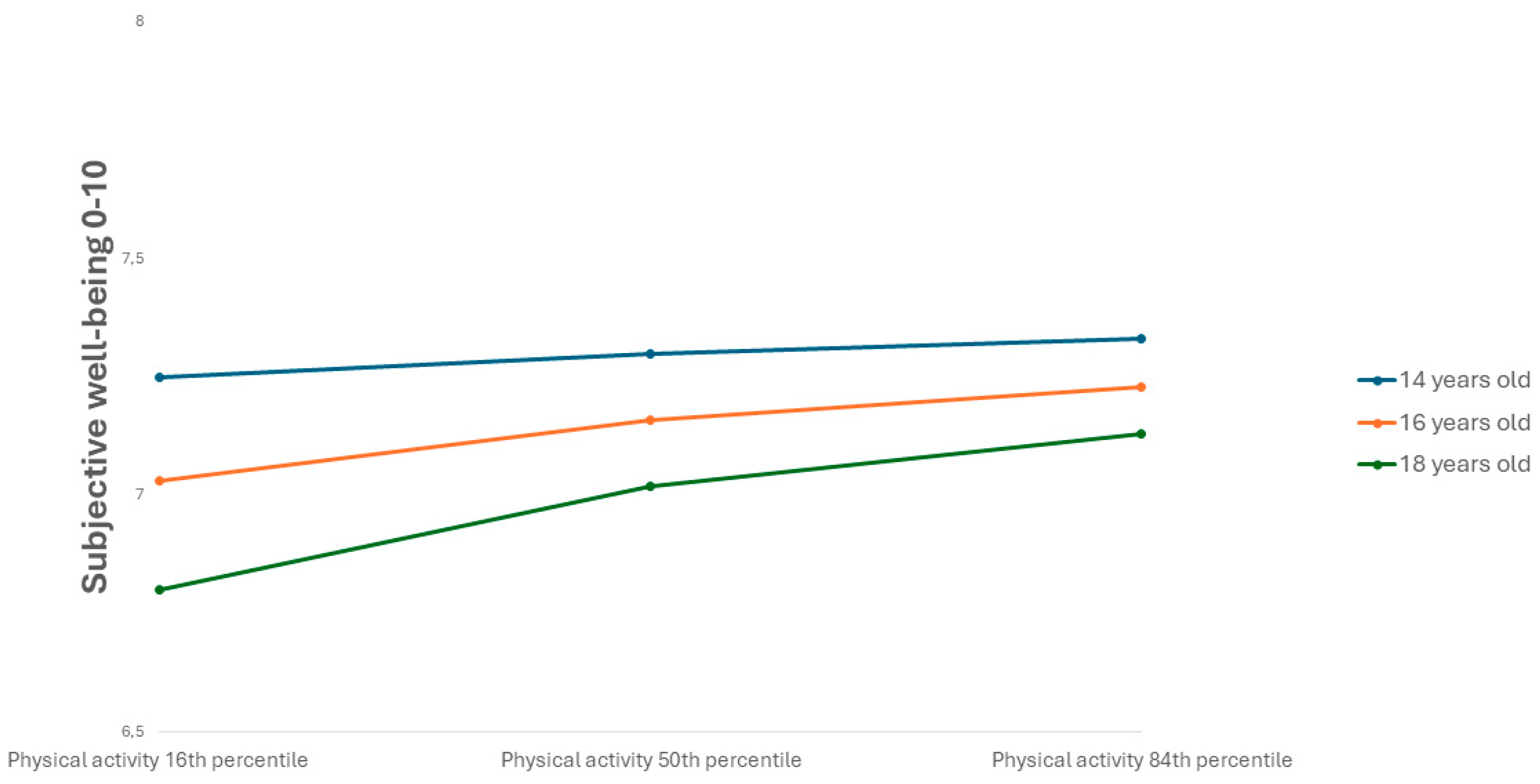

3.4. Moderated Mediation Analyses (Aim 2)

4. Discussion

4.1. Direct Effects of Physical Activity on SWB

4.2. Indirect Effect—Through GSE—Of Physical Activity on SWB

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GSE | General Self-Efficacy |

| SWB | Subjective Well-Being |

References

- Aase, K. N., Gulløy, E., Lorentzen, C. A. R., Bentsen, A., Kristiansen, R., Eik-Åheim, K., Riiser, E. S., Haraldsen, E., & Momrak, E. S. (2021). Ung i Vestfold og Telemark 2021. Kompetansesenter rus—region sør, Vestfold og Telemark fylkeskommune. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken, A. (2019). Idrettens posisjon i ungdomstida. Hvem deltar og hvem slutter i ungdomsidretten? (2). Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA. [Google Scholar]

- Bakken, A. (2024). Ungdata 2024. Nasjonale resultater (NOVA rapport 6/24). NOVA, OsloMet. Available online: https://oda.oslomet.no/oda-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/3145138/Ungdata2024_NasjonaleResultater_UU.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Bakken, A., Frøyland, L. R., & Sletten, M. A. (2016). Sosiale forskjeller i unges liv. Hva sier Ungdata-undersøkelsene? (3/2016). NOVA, OsloMet. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1995). Self-efficacy in changing societies. Cambridge University Press. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucsn-ebooks/detail.action?docID=891897 (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of personality. In L. Pervin, & O. John (Eds.), Handbok of personality (Vol. 2, pp. 154–196). Guilford Publications. Available online: https://admin.umt.edu.pk/Media/Site/STD1/FileManager/OsamaArticle/26august2015/Bandura1999HP.pdf (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Bang, L., Furu, K., Handal, M., Torgersen, L., Støle, H. S., Surèn, P., Odsbu, I., & Hartz, I. (2024). Psykiske plager og lidelser hos barn og unge. In Folkehelserapporten—Helsetilstanden i Norge. Folkehelseinstituttet. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/he/folkehelserapporten/psykisk-helse/psykisk-helse-hos-barn-og-unge/ (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Biddle, S. J. H., Ciaccioni, S., Thomas, G., & Vergeer, I. (2019). Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: An updated review of reviews and an analysis of causality. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 146–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binay, Ş., & Yiğit, R. (2016). Relationship between adolescents’ health promoting lifestyle behaviors and self-efficacy. The Journal of Pediatric Research, 3(4), 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohnert, A., Fredricks, J., & Randall, E. (2010). Capturing unique dimensions of youth organized activity involvement: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Review of Educational Research, 80(4), 576–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsaksen, T., Steigen, A. M., Stea, T. H., Kleppang, A. L., Lien, L., & Leonhardt, M. (2023). Negative social media-related experiences and lower general self-efficacy are associated with depressive symptoms in adolescents. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1037375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, F. C., Al-Ansari, S. S., Biddle, S., Borodulin, K., Buman, M. P., Cardon, G., Carty, C., Chaput, J.-P., Chastin, S., Chou, R., Dempsey, P. C., DiPietro, L., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Friedenreich, C. M., Garcia, L., Gichu, M., Jago, R., Katzmarzyk, P. T., … Willumsen, J. F. (2020). World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(24), 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, E. G., Ridler, I., Ford, T. J., & Stringaris, A. (2023). Editorial perspective: When is a ‘small effect’ actually large and impactful? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 64(11), 1643–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallo, F., Dalmasso, P., Ottová-Jordan, V., Brooks, F., Mazur, J., Välimaa, R., Gobina, I., Gaspar de Matos, M., Raven-Sieberer, U., & the Positive Health Focus Group. (2015). Trends in life satisfaction in European and North-American adolescents from 2002 to 2010 in over 30 countries. European Journal of Public Health, 25(Suppl. S2), 80–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Céspedes, C., Rubio, A., Viñas, F., Cerrato, S. M., Lara-Órdenes, E., & Ríos, J. (2021). Relationship between self-concept, self-efficacy, and subjective well-being of native and migrant adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 620782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.-P., Willumsen, J., Bull, F., Chou, R., Ekelund, U., Firth, J., Jago, R., Ortega, F. B., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2020). 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour for children and adolescents aged 5–17 years: Summary of the evidence. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17(1), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4(1), 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. W. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, H., Booth, J. N., Duncan, A., Fawkner, S., & Niven, A. (2019). The effect of resistance training interventions on ‘the self’ in youth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine—Open, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conley, M. I., Hindley, I., Baskin-Sommers, A., Gee, D. G., Casey, B. J., & Rosenberg, M. D. (2020). The importance of social factors in the association between physical activity and depression in children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 14, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative & mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Crone, E. A., Green, K. H., Van De Groep, I. H., & Van Der Cruijsen, R. (2022). A neurocognitive model of self-concept development in adolescence. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 4(1), 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C., Molcho, M., Boyce, W., Holstein, B., Torsheim, T., & Richter, M. (2008). Researching health inequalities in adolescents: The development of the health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) family affluence scale. Social Science & Medicine, 66(6), 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C., & Morgan, A. (2020). A bio-ecological framing of evidence on the determinants of adolescent mental health—A scoping review of the international Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) study 1983–2020. SSM—Population Health, 12, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, L. P., Vanderloo, L., Moore, S., & Faulkner, G. (2019). Physical activity and depression, anxiety, and self-esteem in children and youth: An umbrella systematic review. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 16, 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Liu, Y., Chen, R., & Wang, Y. (2023). The Relationship between physical activity and life satisfaction among university students in China: The mediating role of self-efficacy and resilience. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., Shigehiro, O., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dishman, R. K., & O’Connor, P. J. (2009). Lessons in exercise neurobiology: The case of endorphins. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 2(1), 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R., Dou, K., & Luo, J. (2023). Construction of a model for adolescent physical and mental health promotion based on the multiple mediating effects of general self-efficacy and sleep duration. BMC Public Health, 23, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooris, M., Kokko, S., & Baybutt, M. (2022). Theoretical grounds and practical principles of setting-based approach. In S. Kokko, & M. Baybutt (Eds.), Handbook of setting-based health promotion (pp. 23–44). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1997). Young adolescent development. In J. L. Irvin (Ed.), What current research says to the middel level practitioner (pp. 15–29). National Middel School Assosiation. [Google Scholar]

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, M., Ghazinour, M., & Hammarström, A. (2018). Different uses of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory in public mental health research: What is their value for guiding public mental health policy and practice? Social Theory & Health, 16(4), 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M. B., Allan, V., Erickson, K., Martin, L. J., Budziszewski, R., & Côté, J. (2017). Are all sport activities equal? A systematic review of how youth psychosocial experiences vary across differing sport activities. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(3), 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics. Sage Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2008). Participation in Extracurricular activities in the middle school years: Are there developmental benefits for African American and European American youth? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(9), 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frøyland, L. R. (2017). Ungdata—Lokale ungdomsundersøkelser. NOVA. Available online: https://www.ungdata.no/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Ungdata-Dokumentasjonsrapport-2010-2019-PDF-1.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Fu, W., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Li, D., Wang, G., Liu, Y., Zhang, T., & Zheng, Y. (2023). The influence of different physical exercise amounts on learning burnout in adolescents: The mediating effect of self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1089570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, C. R., Cooper, R., Craig, L., Elliott, J., Kuh, D., Richards, M., Starr, J. M., Whalley, L. J., & Deary, I. J. (2012). Cognitive function in childhood and lifetime cognitive change in relation to mental wellbeing in four cohorts of older people. PLoS ONE, 7(9), e44860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasaas, E., Rohde, G., Haraldstad, K., Helseth, S., Småstuen, M. C., Skarstein, S., & Mikkelsen, H. T. (2023). Sleep duration in schooldays is associated with health-related quality of life in norwegian adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pediatrics, 23, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasaas, E., & Sandbakk, Ø. (2024). Adherence to physical activity recommendations and associations with self-efficacy among Norwegian adolescents: Trends from 2017 to 2021. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1382028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasaas, E., Skarstein, S., Mikkelsen, H. T., Småstuen, M. C., Rohde, G., Helseth, S., & Haraldstad, K. (2022). The relationship between stress and health-related quality of life and the mediating role of self-efficacy in Norwegian adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 20, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guddal, M. H., Stensland, S. Ø, Småstuen, M. C., Johnsen, M. B., Zwart, J.-A., & Storheim, K. (2019). Physical activity and sport participation among adolescents: Associations with mental health in different age groups. Results from the Young-HUNT study: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open, 9(9), e028555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S., Fu, H., & Guo, K. (2024). Effects of physical activity on subjective well-being: The mediating role of social support and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 6, 1362816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, G. E., Colquhoun, L., Lancastle, D., Lewis, N., & Tyson, P. J. (2021). Review: Physical activity interventions for the mental health and well-being of adolescents—A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 26(4), 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, A. J., Kern, M. L., & Turnbull, D. A. (2019). Can physical activity help explain the gender gap in adolescent mental health? A cross-sectional exploration. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 16, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldstad, K., Kvarme, L. G., Christophersen, K.-A., & Helseth, S. (2019). Associations between self-efficacy, bullying and health-related quality of life in a school sample of adolescents: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Second edition: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helmerhorst, H. H. J., Brage, S., Warren, J., Besson, H., & Ekelund, U. (2012). A systematic review of reliability and objective criterion-related validity of physical activity questionnaires. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9(1), 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, F. K. W., Louie, L. H. T., Chow, C. B., Wong, W. H. S., & Ip, P. (2015). Physical activity improves mental health through resilience in Hong Kong Chinese adolescents. BMC Pediatrics, 15, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeltje, C. O., Zubrick, S. R., Silburn, S. R., & Garton, A. F. (1996). Generalized self-efficacy: Family and adjustment correlates. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(4), 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honmore, V. M., & Jadhav, M. G. (2017). Self-efficacy and emotional intelligence among college youth with respect to family type and gender. Indian Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(4), 587–590. [Google Scholar]

- King, N., Davison, C. M., & Pickett, W. (2021). Development of a dual-factor measure of adolescent mental health: An analysis of cross-sectional data from the 2014 Canadian Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study. BMJ Open, 11(9), e041489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krokstad, S., Weiss, D. A., Krokstad, M. A., Rangul, V., Kvaløy, K., Ingul, J. M., Bjerkeset, O., Twenge, J., & Sund, E. R. (2022). Divergent decennial trends in mental health according to age reveal poorer mental health for young people: Repeated cross-sectional population-based surveys from the HUNT Study, Norway. BMJ Open, 12(5), e057654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, B., Robinson, R., & Till, S. (2015). Physical activity and health in adolescence. Clinical Medicine, 15(3), 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusier, A. O., Ubbesen, T. R., & Folker, A. P. (2024). Understanding mental health promotion in organized leisure communities for young people: A realist review. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1336736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvarme, L. G., Haraldstad, K., Helseth, S., Sørum, R., & Natvig, G. K. (2009). Associations between general self-efficacy and health-related quality of life among 12-13-year-old school children: A cross-sectional survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(1), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langeland, E., & Vinje, H. F. (2012). The significance of salutogenesis and well-being in mental health promotion: From theory to practice. In C. L. M. Keyes (Ed.), Mental well-being: International contributions to the study of positive mental health (pp. 299–329). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, K. A., & Currie, C. (2014). Reliability and validity of an adapted version of the cantril ladder for use with adolescent samples. Social Indicators Research, 119(2), 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M., Wu, L., & Ming, Q. (2015). How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(8), e0134804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, C. A. N., Bauger, L., & Ambugo, E. (n.d.-a). Effect of family socio-economic status on subjective well-being among Norwegian adolescents: Mediation and moderation effects by general self-efficacy from a gendered perspective. BMC Public Health. Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Lorentzen, C. A. N., Berntsen, A., Gulløy, E., & Øvergård, K. I. (n.d.-b). Environmental and socio-demographic influences on general self-efficacy in norwegian adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. In submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Lönnfjord, V., & Hagquist, C. (2018). The psychometric properties of the swedish version of the general self-efficacy scale: A Rasch analysis based on adolescent data. Current Psychology, 37(4), 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lubans, D., Richards, J., Hillman, C., Faulkner, G., Beauchamp, M., Nilsson, M., Kelly, P., Smith, J., Raine, L., & Biddle, S. (2016). Physical activity for cognitive and mental health in youth: A systematic review of mechanisms. Pediatrics, 138, e20161642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luszczynska, A., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). General self-efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from five countries. International Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, O. J. (2021). Deconstructing scandinavia’s ‘achievement generation’ a youth mental health crisis? Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Marquez, D. X., Aguiñaga, S., Vásquez, P. M., Conroy, D. E., Erickson, K. I., Hillman, C., Stillman, C. M., Ballard, R. M., Sheppard, B. B., Petruzzello, S. J., King, A. C., & Powell, K. E. (2020). A systematic review of physical activity and quality of life and well-being. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(5), 1098–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, E. C., Hagan, E., Gottlieb, L. M., Tan, M. L., Vlahov, D., Adler, N., & Glymour, M. M. (2021). Powering population health research: Considerations for plausible and actionable effect sizes. SSM—Population Health, 14, 100789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meland, E., Haugland, S., & Breidablik, H. (2007). Body image and perceived health in adolescence. Health Education Research, 22(3), 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, H. T., Haraldstad, K., Helseth, S., Skarstein, S., Småstuen, M. C., & Rohde, G. (2020). Health-related quality of life is strongly associated with self-efficacy, self-esteem, loneliness, and stress in 14–15-year-old adolescents: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 18(1), 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K. K. (2022). Exploring the association between curiosity and subjective well-being: The mediating role of self-efficacy beliefs in Hindi-speaking youth. Current Psychology, 43, 13861–13870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moksnes, U. K., Eilertsen, M.-E. B., Ringdal, R., Bjørnsen, H. N., & Rannestad, T. (2019). Life satisfaction in association with self-efficacy and stressor experience in adolescents—Self-efficacy as a potential moderator. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(1), 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, B., Dudley, D., & Woodcock, S. (2023). The effects of a martial arts-based intervention on secondary school students’ self-efficacy: A Randomised controlled trial. Philosophies, 8(3), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhr, A., Anthun, K. S., Lillefjell, M., & Sund, E. R. (2020). Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in Norwegian adolescents’ mental health from 2014 to 2018: A repeated cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nes, R. B., Hanen, T., & Barstad, A. (2018). Livskvalitet. Anbefalinger for et bedre målesystem (IS-2727). Helsedirektoratet. Available online: https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/livskvalitet-anbefalinger-for-et-bedre-malesystem/Livskvalitet%20%E2%80%93%20Anbefalinger%20for%20et%20bedre%20m%C3%A5lesystem.pdf/_/attachment/inline/e6f19f43-42f9-48ce-a579-2389415a2432:8d0fbf977b7dbd30e051662c815468072fb6c12c/Livskvalitet%20%E2%80%93%20Anbefalinger%20for%20et%20bedre%20m%C3%A5lesystem.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2023).

- Neumann, R. J., Ahrens, K. F., Kollmann, B., Goldbach, N., Chmitorz, A., Weichert, D., Fiebach, C. J., Wessa, M., Kalisch, R., Lieb, K., Tüscher, O., Plichta, M. M., Reif, A., & Matura, S. (2022). The impact of physical fitness on resilience to modern life stress and the mediating role of general self-efficacy. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 272(4), 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. (2024a, January 9). Local Youth Survey 2010–2023, project number 2236. Available online: https://surveybanken.sikt.no/en/study/NSD3157/1?file=9c72d168-67ae-4c15-82d9-738535771af9_4&type=studyMetadata (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- Norwegian Agency for Shared Services in Education and Research. (2024b, January 9). Research data. Sikt. Available online: https://sikt.no/en/omrade/research-data (accessed on 9 January 2024).

- NOVA. (2024, April 25). Personvern og forskningsetikk. Ungdata. Available online: https://www.ungdata.no/personvern/ (accessed on 25 April 2024).

- Oberle, E., Ji, X. R., Guhn, M., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Gadermann, A. M. (2019). Benefits of extracurricular participation in early adolescence: Associations with peer belonging and mental health. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(11), 2255–2270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, C., Haller, A.-C., Klasen, F., Hölling, H., Bullinger, M., & Ravens-Sieberer, U. (2017). Risk and protective factors of health-related quality of life in children and adolescents: Results of the longitudinal BELLA study. PLoS ONE, 12(12), e0190363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pajares, F. (1997). Current Directions in Self-efficacy Research. In M. Maehr, & P. R. Pintrich (Eds.), Advances in motivation and achievement (Vol. 10, pp. 1–49). JAI Press. Available online: https://www.dynaread.com/current-directions-in-self-efficacy-research (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS (7th ed.). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paluska, S. A., & Schwenk, T. L. (2000). Physical activity and mental health. Sports Medicine, 29(3), 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panza, M. J., Graupensperger, S., Agans, J. P., Doré, I., Vella, S. A., & Evans, M. B. (2020). Adolescent sport participation and symptoms of anxiety and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 42(3), 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potrebny, T., Wiium, N., Haugstvedt, A., Sollesnes, R., Torsheim, T., Wold, B., & Thuen, F. (2019). Health complaints among adolescents in Norway: A twenty-year perspective on trends. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, C., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2017). Life satisfaction. In Encyclopedia of adolescence (Vol. 1, pp. 1–12). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Reigal, R. E., Moral-Campillo, L., Morillo-Baro, J. P., Juárez-Ruiz de Mier, R., Hernández-Mendo, A., & Morales-Sánchez, V. (2020). Physical exercise, fitness, cognitive functioning, and psychosocial variables in an adolescent sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reigal, R. E., Videra, A., & Gil, J. (2014). Physical exercise, general self-efficacy and life satisfaction in adolescence. International Journal of Medicine & Science of Physical Activity & Sport/Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de La Actividad Física y Del Deporte, 14(55), 561–576. [Google Scholar]

- Reverdito, R. S., Carvalho, H. M., Galatti, L. R., Scaglia, A. J., Gonçalves, C. E., & Paes, R. R. (2017). Effects of youth participation in extra-curricular sport programs on perceived self-efficacy: A multilevel analysis. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 124(3), 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M., Cadenas-Sánchez, C., Estévez-López, F., Muñoz, N. E., Mora-Gonzalez, J., Migueles, J. H., Molina-García, P., Henriksson, H., Mena-Molina, A., Martínez-Vizcaíno, V., Catena, A., Löf, M., Erickson, K. I., Lubans, D. R., Ortega, F. B., & Esteban-Cornejo, I. (2019). Role of physical activity and sedentary behavior in the mental health of preschoolers, children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 49(9), 1383–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røysamb, E., Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1998). Norwegian version of the general perceved self-efficacy scale. Available online: https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/norway.htm (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Scholz, U., Gutiérrez-Doña, B., Sud, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2002). Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Asessment, 18(3), 242–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R. (1999). General perceived self-efficacy in 14 cultures. Available online: https://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/world14.htm (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Schwarzer, R., Bäßler, J., Kwiatek, P., Schröder, K., & Zhang, J. X. (1997). The assessment of optimistic self-beliefs: Comparison of the German, Spanish, and Chinese versions of the general self-efficacy scale. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 46(1), 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304930542_Generalized_Self-Efficacy_Scale (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- Schwarzer, R., & Scholz, U. (2000, online). Cross-cultural assessment of coping resources: The general perceived self-efficacy scale. First Asian Congress of Health Psychology: Health Psychology amd Culture, Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, T., & Zhou, X. (2023). Correlates of physical activity habits in adolescents: A systematic review. Frontiers in Physiology, 14, 1131195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, S., Ng, E. D., & Wong, C. H. J. (2022). Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(2), 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, A. T., Kealy, C., Ranta, M., Benner, A. D., Menesini, E., & Schoon, I. (2023). Intra- and interpersonal factors and adolescent wellbeing during COVID-19 in three countries. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 17(10), e12821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steene-Johannessen, J., Anderssen, S. A., Bratteteig, M., Dalhaug, M., Andersen, I. D., Andersen, O. K., Kolle, E., & Dalene, K. E. (2019). Nasjonalt overvåkingssystem for fysisk aktivitet og fysisk form: Kartlegging av fysisk aktivitet, sedat tid og fysisk form blant barn og unge 2018 (ungKan3). Norges Idrettshøyskole and Folkehelseinstituttet. Available online: https://www.fhi.no/globalassets/bilder/rapporter-og-trykksaker/2019/ungkan3_rapport_final_27.02.19.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Steigen, A. M., Finbråten, H. S., & Kleppang, A. L. (2022). Using Rasch analysis to assess the psychometric properties of a five-item version of the general self-efficacy scale in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D. (1992). Establishing and maintaining healthy environments: Toward a social ecology of health promotion. American Psychologist, 47(1), 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokols, D. (2000). Social ecology and behavioral medicine: Implications for training, practice, and policy. Behavioral Medicine, 26(3), 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S. K. M., Hui, E. K. P., & Law, B. C. M. (2012). Self-efficacy as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012(1), 452327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Sluijs, E. M. F., Ekelund, U., Crochemore-Silva, I., Guthold, R., Ha, A., Lubans, D., Oyeyemi, A. L., Ding, D., & Katzmarzyk, P. T. (2021). Physical activity behaviours in adolescence: Current evidence and opportunities for intervention. Lancet, 398(10298), 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S. A., Sutcliffe, J. T., Fernandez, D., Liddelow, C., Aidman, E., Teychenne, M., Smith, J. J., Swann, C., Rosenbaum, S., White, R. L., & Lubans, D. R. (2023). Context matters: A review of reviews examining the effects of contextual factors in physical activity interventions on mental health and wellbeing. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 25, 100520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselska, Z., Madarasova Geckova, A., Reijneveld, S. A., & van Dijk, J. P. (2011). Aspects of self differ among physically active and inactive youths. International Journal of Public Health, 56(3), 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalonga-Olives, E., Rojas-Farreras, S., Vilagut, G., Palacio-Vieira, J. A., Valderas, J. M., Herdman, M., Ferrer, M., Rajmil, L., & Alonso, J. (2010). Impact of recent life events on the health related quality of life of adolescents and youths: The role of gender and life events typologies in a follow-up study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wachs, S., Görzig, A., Wright, M. F., Schubarth, W., & Bilz, L. (2020). Associations among Adolescents’ Relationships with Parents, Peers, and Teachers, Self-Efficacy, and Willingness to Intervene in Bullying: A Social Cognitive Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., Li, Y., Zhang, T., & Luo, J. (2022). The relationship among college students’ physical exercise, self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warner, L. M., & Schwarzer, R. (2021). Self-Efficacy and Health. In L. Cohen (Ed.), The wiley encyclopedia of health psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 605–613). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. Available online: http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ucsn-ebooks/detail.action?docID=6379819 (accessed on 5 September 2024).

- White, R. L., Vella, S., Biddle, S., Sutcliffe, J., Guagliano, J. M., Uddin, R., Burgin, A., Apostolopoulos, M., Nguyen, T., Young, C., Taylor, N., Lilley, S., & Teychenne, M. (2024). Physical activity and mental health: A systematic review and best-evidence synthesis of mediation and moderation studies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 21(1), 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2020). WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240015128 (accessed on 22 October 2023).

- World Health Organization. (2021, November 17). Mental health of adolescents. World health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240049338 (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- World Health Organization. (2023). Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA!): Guidance to support country implementation. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. Y., Han, L. H., Zhang, J. H., Luo, S., Hu, J. W., & Sun, K. (2017). The influence of physical activity, sedentary behavior on health-related quality of life among the general population of children and adolescents: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 12(11). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S. N. (2007). How to increase serotonin in the human brain without drugs. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience: JPN, 32(6), 394–399. [Google Scholar]

- Ystrom, E., Niegel, S., Klepp, K.-I., & Vollrath, M. E. (2008). The impact of maternal negative affectivity and general self-efficacy on breastfeeding: The Norwegian mother and child cohort study. The Journal of Pediatrics, 152(1), 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., & Huo, Y. (2022). Chinese Youths’ Physical Activity and Flourishing During COVID-19: The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life and Self-Efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 867599. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.867599 (accessed on 22 October 2023). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, S. L., Tang, A. R., Richard, K. E., Grisham, C. J., Kuhn, A. W., Bonfield, C. M., & Yengo-Kahn, A. M. (2021). The behavioral, psychological, and social impacts of team sports: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 49(3), 246–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Not Included in Study Sample | Included in Study Sample (n = 18,146) | M Diff | 95 % CI M Diff | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Physical activity | 2680 | 4.33 | 1.40 | 4.54 | 1.23 | −0.21 | −0.27 | −0.16 |

| General self-efficacy | 1125 | 2.82 | 0.71 | 2.93 | 0.62 | −0.11 | −0.15 | −0.07 |

| Subjective well-being | 3446 | 6.83 | 2.32 | 7.10 | 1.92 | −0.28 | −0.36 | −0.19 |

| Age | 3223 | 3.19 | 1.62 | 3.30 | 1.61 | −0.12 | −0.18 | −0.06 |

| Socio-economic status | 3569 | 1.89 | 0.57 | 2.02 | 0.53 | −0.13 | −0.15 | −0.11 |

| Social support | 2799 | 1.60 | 0.67 | 1.73 | 0.57 | −0.12 | −0.15 | −0.10 |

| n | % | n | % | Chi-square results | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Boys | 1994 | 58.1 | 8782 | 48.4 | ||||

| Girls | 1440 | 41.9 | 9364 | 51.6 | X2(1, 22,028) = 108.01, p < 0.001 | |||

| Variables | Total Sample n = 18,146 | Boys n = 8782 | Girls n = 9364 | M Diff. [95% CI] | 14–16 years n = 9835 | 17–19 years n = 8311 | M Diff. [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD/n (%) | M ± SD/n (%) | M ± SD/n (%) | M ± SD/n (%) | M ± SD/n (%) | |||

| Subjective well-being 0–10 | 7.10 ± 1.92 | 7.52 ± 1.78 | 6.71 ± 1.96 | −0.81 [−0.87, −0.76] | 7.16 ± 1.97 | 7.03 ± 1.86 | −0.13 [−0.18, −0.07] |

| Physical activity 1–6 | 4.54 ± 1.23 | 4.69 ± 1.24 | 4.40 ± 1.22 | −0.15 [−0.33, −0.25] | 4.59 ± 1.21 | 4.48 ± 1.26 | −0.11 [−0.15, −0.08] |

| General self-efficacy 1–4 | 2.93 ± 0.62 | 3.07 ± 0.61 | 2.79 ± 0.59 | −0.28 [−0.29, −0.26] | 2.89 ± 0.63 | 2.97 ± 0.60 | 0.08 [0.05, 0.09] |

| Gender | |||||||

| Boys | 8782 (48.4) | 4857 (49.4) | 3925 (47.2) | ||||

| Girls | 9364 (51.6) | 4978 (50.6) | 4386 (52.8) * | ||||

| Age 14–19 | 16.30 ± 1.61 | 16.24 ± 1.58 | 16.36 ± 1.64 | 0.12 [0.07, 0.16] | |||

| Socio-economic status 0–3 | 2.02 ± 0.53 | 2.00 ± 0.52 | 2.03 ± 0.54 | 0.03 [0.02, 0.05] | 2.05 ± 0.51 | 1.97 ± 0.55 | −0.08 [−0.09, −0.06] |

| Social support 0–2 | 1.73 ± 0.57 | 1.75 ± 0.56 | 1.71 ± 0.58 | −0.04 [−0.05, −0.02] | 1.69 ± 0.59 | 1.77 ± 0.54 | 0.08 [0.05, 0.09] |

| No | 1137 (6.3) | 522 (5.9) | 615 (6.6) | 686 (7.0) | 451 (5.4) | ||

| Don’t know | 2677 (14.8) | 1184 (13.5) | 1493 (16.0) | 1631 (16.6) | 1046 (12.6) | ||

| Yes | 14,332 (79) | 7076 (80.6) | 7256 (77.5) | 7518 (76.4) | 6814 (82.0) |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Subjective well-being | ||||||

| 2. Physical activity | 0.16 * | |||||

| 3. General self-efficacy | 0.35 * | 0.20 * | ||||

| 4. Gender | −0.21 * | −0.12 * | −0.23 * | |||

| 5. Age | −0.04 * | −0.04 * | 0.07 * | 0.04 * | ||

| 6. Socio-economic status | 0.10 * | 0.21 * | 0.10 * | 0.03 * | −0.08 * | |

| 7. Social support | 0.30 * | 0.10 * | 0.22 * | −0.04 * | 0.07 * | 0.08 * |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys (n = 8782) | 1. Subjective well-being | |||||

| 2. Physical activity | 0.12 * | |||||

| 3. General self-efficacy | 0.25 * | 0.19 * | ||||

| 4. Age | −0.10 * | −0.01 * | 0.09 * | |||

| 5. Socio-economic status | 0.09 * | 0.19 * | 0.11 * | −0.06 * | ||

| 6. Social support | 0.27 * | 0.11 * | 0.19 * | 0.01 * | 0.09 * | |

| Girls (n = 9364) | 1. Subjective well-being | |||||

| 2. Physical activity | 0.15 * | |||||

| 3. General self-efficacy | 0.38 * | 0.18 * | ||||

| 4. Age | −0.01 * | −0.06 * | 0.07 * | |||

| 5. Socio-economic status | 0.12 * | 0.24 * | 0.11 * | −0.09 * | ||

| 6. Social support | 0.32 * | 0.09 * | 0.25 * | 0.13 * | 0.07 * |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14–16 years (n = 9835) | 1. Subjective well-being | |||||

| 2. Physical activity | 0.13 * | |||||

| 3. General self-efficacy | 0.38 * | 0.19 * | ||||

| 4. Gender | −0.25 * | −0.11 * | −0.22 * | |||

| 5. Socio-economic status | 0.08 * | 0.21 * | 0.09 * | 0.05 * | ||

| 6. Social support | 0.32 * | 0.14 * | 0.24 * | −0.08 * | 0.08 * | |

| 17–19 years (n = 8311) | 1. Subjective well-being | |||||

| 2. Physical activity | 0.18 * | |||||

| 3. General self-efficacy | 0.31 * | 0.22 * | ||||

| 4. Gender | −0.17 * | −0.13 * | −0.23 * | |||

| 5. Socio-economic status | 0.11 * | 0.21 * | 0.12 * | 0.02 | ||

| 6. Social support | 0.28 * | 0.11 * | 0.19 * | 0.02 | 0.09 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fossli, K.; Lorentzen, C.A.N. General Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of Physical Activity’s Impact on Well-Being Among Norwegian Adolescents: A Gender and Age Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091239

Fossli K, Lorentzen CAN. General Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of Physical Activity’s Impact on Well-Being Among Norwegian Adolescents: A Gender and Age Perspective. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091239

Chicago/Turabian StyleFossli, Karianne, and Catherine A. N. Lorentzen. 2025. "General Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of Physical Activity’s Impact on Well-Being Among Norwegian Adolescents: A Gender and Age Perspective" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091239

APA StyleFossli, K., & Lorentzen, C. A. N. (2025). General Self-Efficacy as a Mediator of Physical Activity’s Impact on Well-Being Among Norwegian Adolescents: A Gender and Age Perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1239. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091239