1. Introduction

Public organizations today face intense pressure to innovate in response to complex societal challenges and rising public expectations (

Lindquist, 2022). Governments are urged to devise creative solutions for issues ranging from digital service delivery to climate resilience; yet, bureaucratic structures often impede such innovation (

Fleischer & Wanckel, 2024). Rigid hierarchies, formal rules, and risk-averse cultures can stifle employees’ creativity and adaptability (

Criado et al., 2025). Consequently, a persistent challenge in the public sector is unlocking innovative work behavior at the individual level, despite the inertia inherent in bureaucratic rigidity (

Cinar et al., 2021). This dilemma highlights the need to understand what motivates public employees to generate and implement new ideas within traditionally inflexible organizations.

A promising motivator of innovative work behavior in the public sector is organizational identification—the degree to which individuals internalize their organization’s values and perceive themselves as integral members of it (

Yang & Mostafa, 2024). Drawing on social identity theory, employees who view their organization as a core part of their self-concept are more likely to align their behavior with organizational goals and invest effort into its success (

Ellemers et al., 2004). In this context, identification fosters a sense of shared purpose that drives individuals to exceed formal duties and engage in proactive, improvement-oriented actions (

Srirahayu et al., 2023). While much existing literature has concentrated on public service motivation or organizational culture as drivers of innovation (

Miao et al., 2018;

Wynen et al., 2017), the role of identification remains relatively underexplored. In environments where external incentives are limited and bureaucratic constraints prevail, a robust psychological attachment to the organization can serve as a significant intrinsic motivator. This study aims to address this gap by examining how organizational identification contributes to innovative work behavior in public organizations.

Although employee identification provides a psychological basis for innovation, this potential does not automatically translate into tangible innovative work behavior (

G. Zhang & Wang, 2022). For organizational identification to lead to innovative work behavior, a contextual condition is often necessary—one that reinforces employees’ shared sense of purpose and aligns their psychological attachment with organizational goals. Charismatic leadership fulfills this role by fostering emotional and motivational alignment with the organization’s mission. Through visionary communication, symbolic actions, and confidence in followers’ capabilities, charismatic leaders frame innovation as a collective pursuit rather than an individual risk (

Meslec et al., 2020;

Tavares et al., 2021). This is particularly crucial in the public sector, where hierarchical rigidity and risk aversion can suppress creative behavior. For employees with strong organizational identification, charismatic leadership transforms passive alignment into proactive engagement. It elevates innovation to an authentic expression of shared values and institutional purpose, thereby enhancing its moral and emotional resonance (

Conger & Kanungo, 1998). This study is the first to empirically test the interaction between charismatic leadership and organizational identification, demonstrating how charisma amplifies the identity-based pathway to employee innovative work behavior in public organizations.

This research is situated in the context of South Korean public organizations, which are characterized by strong hierarchical structures, collectivist cultural norms, and centralized administrative control. These features provide a theoretically meaningful boundary condition for understanding the proposed relationships: in such environments, employees may be especially responsive to value-based, emotionally resonant leadership that aligns with their internalized organizational identity. Rather than viewing the Korean setting as a sampling limitation, this study conceptualizes it as a context where the synergy between charismatic leadership and organizational identification is particularly salient—thus offering insights that are transferable to similarly structured bureaucratic systems.

Based on this theoretical framework, this study presents the research model shown in

Figure 1. The primary objective is to examine how organizational identification relates to innovative work behavior among public sector employees and to assess whether charismatic leadership moderates this relationship. In the model, organizational identification is the independent variable, innovative work behavior is the dependent variable, and charismatic leadership is the moderating variable that may strengthen the positive effect of identification on innovation.

This study contributes to the behavioral public administration literature by examining the conditions under which organizational identification translates into innovative work behavior in bureaucratic environments. While previous research has treated employee motivation and leadership as separate influences on innovation, our approach integrates the two by theorizing that organizational identification provides intrinsic motivation, though its behavioral consequences depend on contextual activation. Drawing on social identity theory, we argue that identification alone serves as a latent motivational resource. Building on leadership theory, we conceptualize charismatic leadership as the mechanism that activates this latent resource by embodying institutional values, inspiring confidence, and fostering a climate where risk-taking is encouraged. Thus, charismatic leadership acts as a contextual force that determines whether identification remains symbolic or evolves into innovative action.

Using large-scale survey data from public organizations in South Korea, this study explores how internal motivation and leadership dynamics jointly foster innovation among government employees. Although situated in a specific national context, the findings provide broader insights for public organizations operating in rule-bound or structurally rigid environments. By highlighting the interplay between psychological attachment and leadership conditions, this study elucidates how innovative work behavior can emerge even within traditionally formalized and hierarchical systems.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature on organizational identification, innovative work behavior, and charismatic leadership while developing research hypotheses. The third section outlines the research methods, including data sources, measurement, and analytical procedures. The fourth section presents the results of empirical analysis. The final section discusses the implications of the findings and the study’s theoretical and practical contributions.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Sample

This study empirically tested its hypotheses using data from the 2024 Comparative Survey on Perceptions of Public and Private Sector Employees in Korea, conducted by the Korea Institute of Public Administration (KIPA). Although the original survey targeted both public and private sector employees, this study focuses exclusively on public officials—specifically national and local government employees—making individual public servants the unit of analysis.

The KIPA survey aimed to provide a comprehensive understanding of employees’ perceptions and attitudes across various topics, including human resource practices, organizational behavior, and administrative culture. The questionnaire included a wide array of items measuring core constructs such as organizational identification, proactivity, leadership, decision-making autonomy, goal clarity, procedural and distributive justice, work–life balance, and diversity, equity, and inclusion. These variables establish a strong empirical foundation for examining major themes in public sector organizational behavior. This study specifically concentrates on innovative work behavior, goal clarity, and leadership—areas well-represented in the survey, ensuring content validity.

To ensure robust and representative sampling, the public sector sample was drawn from the 2023 National Census of Public Officials by the Ministry of Personnel Management. The final sample included 1000 individuals—500 national government officials and 500 local government officials. A proportional allocation method was applied, ensuring at least five respondents from each of the Grade 4-and-above and Grade 5 groups to secure sufficient representation across ranks.

The online survey was administered over a three-week period from 11 October to 1 November 2024, resulting in a final valid sample of 1012 public officials, with a 95% confidence level and a ±2.2% margin of error. The sampling design was stratified by key demographic and organizational factors, including level of government (central vs. local), gender, and rank. This rigorous approach enhances the generalizability of the study’s findings to the broader public sector workforce in Korea. The sociodemographic profile of the respondents included in this study is presented in

Table 1.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Innovative Work Behavior

The dependent variable in this study is innovative work behavior, referring to individuals’ proactive efforts to generate and implement new ideas that diverge from conventional methods to address work-related challenges and improve both organizational and individual performance (

Janssen, 2000;

Scott & Bruce, 1994). This concept encompasses more than just idea generation; it includes the creative process of transforming those ideas into tangible changes within the workplace. To measure innovative work behavior, this study utilized the following items: (1) “I try new ways of doing things to perform my job better,” (2) “I come up with new ideas to improve how I do my work,” and (3) “I attempt to introduce changes to key aspects of how my work is carried out.”

3.2.2. Organizational Identification

Organizational identification was assessed by measuring the degree to which public employees psychologically associate themselves with their organization and internalize its successes and failures as their own (

Carmeli & Freund, 2009;

Yang & Mostafa, 2024). Six items were used to capture this construct, emphasizing emotional attachment, collective pride, and self-referential language. Respondents indicated their level of agreement with the statements: (1) “When I hear others criticize my organization, I feel like they are criticizing me,” (2) “I am very interested in what people think about my organization,” (3) “When talking about my organization, I often use ‘we’ rather than ‘the company’ or ‘the office,’”(4) “When my organization succeeds, I feel like I succeed,” (5) “When I hear others praise my organization, it feels like I’m being praised,” and (6) “When there is negative news about my organization, I feel embarrassed.”

3.2.3. Charismatic Leadership

Charismatic leadership, the moderating variable in this study, is defined as a leadership style in which leaders articulate a compelling vision and sense of mission, demonstrate personal sacrifice and risk-taking to realize that vision, and inspire commitment and engagement among organizational members (

Conger & Kanungo, 1998;

Shamir & Howell, 1999). Charismatic leaders are distinguished by their exceptional insight and personal conviction, enabling them to effectively communicate organizational goals while maximizing collective performance through strong motivational influence. In public organizations, this leadership style is reflected in vision-setting, strategic acumen, and dedication to the organization—factors that enhance employees’ intrinsic motivation and public service motivation, ultimately fostering proactive behavior. Charismatic leadership in this study was measured using four items: (1) “My supervisor presents an ambitious strategy and clear goals for the organization” (vision clarification and strategic direction), (2) “My supervisor seizes new opportunities that help the organization achieve its goals” (environmental sensitivity and strategic insight), (3) “My supervisor is willing to make personal sacrifices and take risks for the benefit of the organization” (risk-taking and self-sacrifice), and (4) “My supervisor strives to realize a vision that is both ambitious and attainable” (vision execution and behavioral consistency).

3.2.4. Controls

Several control variables were included to account for individual and organizational factors that could be associated with employees’ innovative work behavior. Gender was controlled (female = 1, male = 0) to capture potential differences in innovation-related attitudes or opportunities across sexes. Job rank was grouped into Grades 8–9, 6–7, and 1–5 to reflect hierarchical status, which may be linked to access to decision-making or innovation roles. Education was classified into five levels—high school or below, associate degree, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, and doctoral degree—since higher education often correlates with increased cognitive flexibility and creativity. Age was divided into five brackets (under 30, 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60 and above) to account for generational differences in adaptability to change or technology. Tenure was categorized as 10 years or less, 20–29 years, and 30 years or more, recognizing that tenure can influence familiarity with institutional norms and the willingness to propose change. Finally, government level was included as a binary variable (local government = 1, central government = 0), as organizational structure and innovation culture may vary across administrative tiers.

3.3. Measurement Reliability and Validity

This study employed a total of 13 items to measure organizational identification, charismatic leadership, and innovative work behavior. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). To evaluate the construct validity of the survey instrument, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted. Prior to factor extraction, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was calculated to determine the appropriateness of the data for factor analysis. The overall KMO values for each latent variable exceeded the commonly accepted threshold of 0.70, indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis.

The criteria for factor extraction were set at eigenvalues greater than or equal to 1.0, and only items with factor loadings of 0.5 or higher were retained. An orthogonal varimax rotation was applied to enhance the interpretability of the factor structure. The analysis identified three distinct latent factors, with all items loading cleanly onto their respective factors. Every item demonstrated a factor loading of 0.5 or higher, confirming the construct validity of the measurement scales. Additionally, reliability analysis indicated satisfactory internal consistency for each factor: Cronbach’s α was 0.828 for organizational identification, 0.893 for charismatic leadership, and 0.849 for innovative work behavior. These results suggest that the measurement items exhibited strong reliability, exceeding the commonly accepted threshold of 0.7. Detailed results of the factor and reliability analyses are presented in

Table 2.

4. Results

Table 3 presents descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for the key variables in this study, particularly focusing on the dependent variable, innovative work behavior. The analysis shows that organizational identification is significantly and positively correlated with innovative work behavior (

r = 0.352,

p < 0.01), suggesting that employees who feel a strong psychological bond with their organization are more likely to engage in discretionary and creative efforts aimed at improvement. Charismatic leadership also shows a meaningful positive correlation with innovative behavior (

r = 0.256,

p < 0.01), implying that leadership style may play an enabling role in motivating innovation. Among the control variables, tenure (

r = 0.228,

p < 0.01), age (

r = 0.231,

p < 0.01), job grade (

r = 0.175,

p < 0.01), and education (

r = 0.129,

p < 0.01) all show small but significant positive correlations with innovative work behavior, while gender (

r = −0.071,

p < 0.01) shows a weak negative correlation. Government level is not significantly correlated with innovative behavior.

To establish a baseline model, Model 1 was developed to evaluate the impact of demographic and organizational control variables on innovative work behavior, alongside the direct influence of charismatic leadership. This initial analysis provides insight into how leadership style and individual characteristics relate to employees’ willingness to innovate. Model 2 introduced the primary independent variable, organizational identification, to determine whether employees’ psychological attachment to their organization contributes to innovative work behavior beyond the effects of leadership and demographic factors. By including this variable, we were able to more accurately estimate the unique contribution of organizational identification. Finally, Model 3 integrated the interaction term between organizational identification and charismatic leadership to test the proposed moderating effect, examining whether the relationship between organizational identification and innovative work behavior varies based on the level of charismatic leadership perceived by employees.

The results from Model 1 in

Table 4 indicate that among the control variables, both education (β = 0.096,

p < 0.01) and age (β = 0.117,

p < 0.01) have a significant positive association with innovative work behavior. This suggests that more educated and older employees are more likely to engage in innovation, possibly due to accumulated knowledge, confidence, or experience that enables them to pursue nonroutine work behaviors. Charismatic leadership also has a strong positive effect on innovative work behavior (β = 0.192,

p < 0.001), indicating that employees are more likely to behave innovatively when led by leaders who are inspirational and vision-driven.

In Model 2, the introduction of the independent variable, organizational identification, reveals a significant positive relationship with innovative work behavior (β = 0.258, p < 0.001). This finding supports Hypothesis 1 that employees who identify strongly with their organization are more likely to go beyond routine responsibilities to contribute creatively. The coefficient for charismatic leadership remains significant (β = 0.119, p < 0.001), further emphasizing its relevance as a direct driver of innovative work behavior.

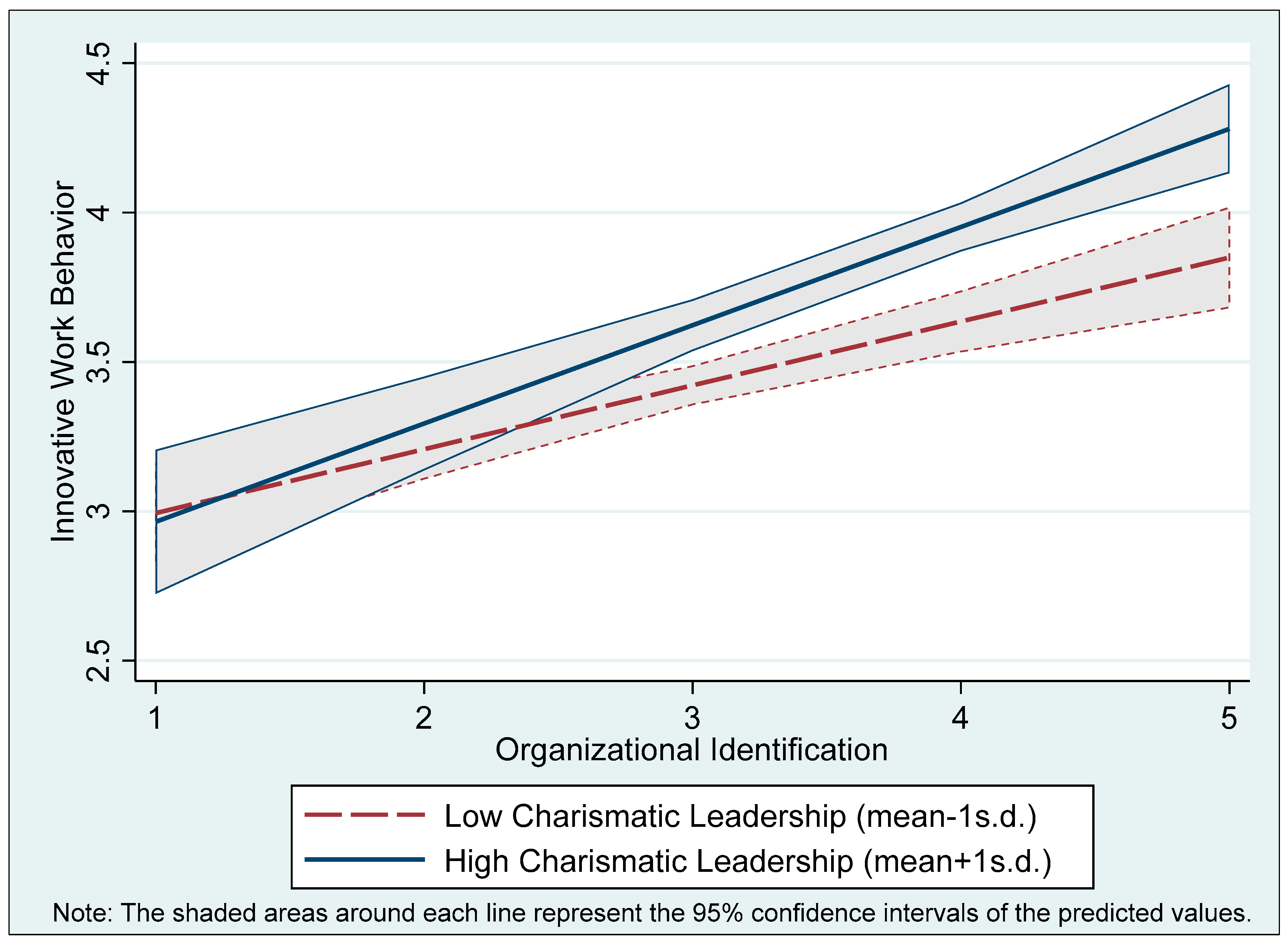

Model 3 introduces the interaction term between organizational identification and charismatic leadership to test the moderating effect. The interaction term is statistically significant (β = 0.060, p < 0.01), suggesting that charismatic leadership strengthens the positive relationship between organizational identification and innovative work behavior. In other words, the influence of organizational identification on innovation is more pronounced when employees perceive their leaders to be charismatic. This result supports Hypothesis 2 that charismatic leadership functions as a contextual enhancer that activates employees’ psychological commitment to innovative action.

Figure 2 visually illustrates how the relationship between organizational identification and innovative work behavior varies with different levels of charismatic leadership. When charismatic leadership is high (mean + 1 standard deviation), the positive association between organizational identification and innovative work behavior becomes more pronounced. As employees’ organizational identification increases, their level of innovative behavior rises more sharply under high-charisma conditions. Conversely, when charismatic leadership is low (mean − 1 standard deviation), the slope of the relationship appears more modest, suggesting a weaker tendency. This pattern implies that charismatic leadership may amplify the psychological mechanisms through which organizational identification relates to innovative work behavior. Although the 95% confidence intervals partially overlap, the divergence between the two lines becomes more evident—particularly when organizational identification exceeds the scale midpoint—indicating that the moderating effect is likely more pronounced at higher levels of identification.

These findings support the interpretation that charismatic leadership functions as a contextual amplifier, enhancing the psychological conditions under which organizational identification translates into innovative work behavior. Charismatic leaders provide emotional framing, intellectual stimulation, and value alignment that activate and magnify the motivational power of identification. When employees feel a strong sense of belonging to the organization, the presence of a visionary and supportive leader increases their confidence to challenge norms, take risks, and pursue novel ideas in the service of collective goals. In such environments, the synergy between identification and charismatic leadership fosters forward-looking, change-oriented behavior. Conversely, in the absence of charismatic leadership, even highly identified employees may lack the psychological safety or inspirational guidance needed to express their attachment through innovation. Thus, charismatic leadership creates the conditions that enable latent organizational identification to manifest as active, creative contributions to organizational progress.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature on behavioral public administration by integrating social identity theory and charismatic leadership theory, providing a more comprehensive understanding of how innovative work behavior arises in public organizations. Traditionally, research on public sector innovation has focused on either intrinsic motivational factors—such as public service motivation or organizational commitment—or on leadership styles that inspire employees to act beyond their formal roles. However, few studies have examined how employee identification and leadership interact to drive innovation. This research addresses that gap by offering both theoretical integration and empirical evidence that demonstrates the effects of organizational identification are significantly shaped by the leadership context.

First, this study extends social identity theory by demonstrating that organizational identification serves as a potent source of intrinsic motivation for innovation. When employees internalize their organization’s mission and values as part of their self-concept, they are more inclined to engage in discretionary behaviors aimed at improving organizational performance. This internalized identity creates a personal stake in the organization’s success, motivating individuals to act proactively, even in environments where external rewards are limited. While prior research has primarily focused on identification’s role in promoting organizational commitment or job satisfaction, this study empirically verifies its relevance to innovation, broadening the applicability of social identity theory within public sector contexts.

Second, this study advances charismatic leadership theory by reframing it as a contextual mechanism of identity activation rather than merely another moderator. Its impact is not uniform; in bureaucratic settings, organizational identification alone does not automatically produce innovation. Instead, innovation occurs when leaders create legitimacy and psychological safety, enabling employees to act on their identity without fear of sanction or failure. Charismatic behaviors—such as articulating a compelling vision, modeling shared values, and symbolically reinforcing group identity—serve as triggers that activate identification into innovative behavior. In doing so, the study contributes to social identity theory by showing that identity-based motivation is conditional rather than automatic, and supports a multiplicative model of employee-driven innovation where leadership interventions are most effective when they activate and channel pre-existing psychological resources.

Finally, this study advances theoretical discourse by moving beyond structural or institutional explanations of public sector innovation, which often emphasize resource availability, regulatory reform, or managerial discretion. Instead, it highlights psychological attachment and leadership framing as internal drivers for innovation, even in constrained environments. This perspective is particularly relevant for public organizations that operate under rigid procedures and hierarchical controls, where formal incentives for innovation may be limited. By focusing on the motivational and symbolic mechanisms that stimulate innovation, the study provides a compelling alternative to purely structural explanations and underscores the importance of behavioral insights in understanding public administration.

5.2. Practical Implications

To promote innovative work behavior in public organizations, it is essential to adopt a human resource strategy that strengthens employees’ psychological attachment to the organization and fosters value-based leadership. While many public sector reforms prioritize structural changes or performance incentives, this study shows that innovation is more effectively nurtured by enhancing two key internal drivers: organizational identification and charismatic leadership. When supported by a cohesive set of HR practices, these factors can create a work environment conducive to creativity, risk-taking, and commitment to public service.

First, value-based recruitment and early socialization are crucial for fostering strong organizational identification. Public agencies should highlight their mission and core values during the hiring process to attract candidates whose personal values align with those of the organization. This value congruence facilitates the internalization of public goals and fosters a sense of belonging from the outset. Supervisors who embody these values are more likely to emerge as inspirational leaders who motivate and mobilize their teams toward innovation.

Second, leadership development programs should intentionally cultivate traits associated with purpose-driven leadership, such as vision articulation, value-based communication, and emotional resonance. These leaders help translate identification into action by reinforcing shared purpose and creating psychological safety. Leadership training should prioritize ethical reasoning and symbolic behavior alongside administrative competence.

Third, performance management and organizational culture must reinforce innovation-oriented behaviors. Evaluation systems should recognize not only task efficiency but also contributions to learning, ethical conduct, and alignment with public values. A supportive culture that normalizes experimentation and celebrates success stories can further sustain innovation. Initiatives like innovation labs and idea-sharing platforms can institutionalize creative behavior and reduce the fear of failure.

However, organizations should also exercise caution. While inspirational leadership can strengthen purpose and engagement, it may also produce unintended side effects, particularly when it takes the form of charismatic authority concentrated in a single figure. Excessive identification with such leaders can foster psychological dependency, diminish critical thinking, and lead to hero worship that undermines collective accountability. These risks are especially pronounced in hierarchical or opaque organizations. To mitigate them, HR strategies should be paired with institutional checks, transparent decision-making, and participatory governance mechanisms that promote distributed leadership and organizational integrity.

By aligning recruitment, leadership development, and performance systems within a cohesive framework, public organizations can create a psychologically engaging environment that encourages innovation while maintaining ethical accountability.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Despite offering novel insights into the interaction between organizational identification and charismatic leadership in shaping innovative work behavior, this study has several limitations that warrant consideration and open avenues for future research.

First, the cross-sectional nature of the data means that the findings should not be interpreted as evidence of causality. While the results demonstrate a statistically significant interaction between organizational identification and charismatic leadership regarding innovative work behavior, they reflect associations rather than causal effects. The direction of influence remains uncertain, and it is plausible that reciprocal or third-variable relationships exist. Moreover, both organizational identification and innovative work behavior are dynamic processes that evolve over time in response to organizational change, leadership transitions, or fluctuations in institutional trust. Future research should adopt longitudinal or experimental designs capable of disentangling the temporal and causal ordering of leadership behavior, identification, and innovation.

Second, the empirical analysis is based exclusively on data from South Korean public organizations, raising concerns about the generalizability of the findings. Given the hierarchical and collectivist nature of Korean administrative culture, the strength of organizational identification and the influence of charismatic leadership may manifest differently in other cultural or institutional settings. Comparative studies across diverse national or sectoral contexts would help clarify the boundary conditions of the proposed relationships.

Third, although this study employed context-relevant items to measure charismatic leadership, it did not use the complete instrument developed by

Conger and Kanungo (

1998), one of the most widely validated scales in the literature. This limitation arose because the survey data were not originally designed to specifically evaluate charismatic leadership but rather to assess general features of organizational management in the public sector. Consequently, only a limited set of items capturing key aspects of charismatic leadership—such as vision clarity, strategic awareness, and consistent, value-driven behavior—were available for analysis. While these items capture essential aspects of charismatic leadership, they do not encompass the full conceptual range of the original scale. Therefore, caution is warranted in interpreting the construct’s validity and comparing the results with studies that used the complete Conger and Kanungo instrument. Future research should consider employing validated, multidimensional measures that more comprehensively reflect the rhetorical, behavioral, and affective dimensions of charismatic leadership.

Fourth, this study conceptualized organizational identification as a relatively stable psychological state. However, identification is likely to evolve over time, influenced by organizational changes, leadership transitions, or shifts in institutional trust. Future research should explore the dynamic nature of identification and its interaction with leadership over time. Such an approach could yield deeper insights into how identity-based mechanisms contribute to sustained innovative work behavior in public organizations.

Fifth, the findings of this study should be interpreted in light of the unique cultural characteristics of the South Korean public sector, which is characterized by strong hierarchical structures and collectivist norms. These features may have amplified the effects of organizational identification and value-based leadership. In such environments, employees are more likely to internalize collective goals, respond sensitively to leadership cues, and perceive innovation as a contribution to group success. Consequently, the observed relationships may differ in more individualistic or egalitarian public sectors, where autonomy and decentralized authority shape distinct motivational dynamics. Future research should examine whether these findings hold across diverse cultural and institutional contexts to better establish the generalizability of the results.

Sixth, while this study emphasizes the positive role of charismatic leadership and organizational identification in promoting innovative work behavior, it also acknowledges the potential downsides of their interaction. In highly hierarchical settings like the Korean public sector, strong identification with a charismatic leader can unintentionally foster conformity, suppress dissent, and encourage hero worship, particularly when emotional appeals override critical evaluation. These unintended consequences highlight the need to approach charismatic leadership not only as a catalyst for innovation but also as a double-edged sword that may reinforce existing power structures or discourage deviance when it threatens group cohesion. Future research should examine this “dark side” more systematically by incorporating measures of dissent tolerance, critical voice, or blind obedience, and by exploring the contextual moderators—such as psychological safety, participatory culture, or leader accountability—that shape whether charisma-activated identification results in constructive or maladaptive outcomes (

X. Zhang et al., 2020). Such balanced theorization would contribute to a more nuanced understanding of when and how charismatic leadership enables identity-driven innovation without compromising organizational reflexivity or ethical vigilance.

Finally, future research would benefit from employing multilevel designs to capture the collective dynamics of identification and leadership climate. While this study focused on individual-level perceptions, organizational identification and leadership are often shared experiences shaped by team norms and agency-wide cultures. Analyzing group- or agency-level effects would help illuminate how shared identity and emotionally resonant leadership collectively influence innovation. This approach would not only enhance explanatory power but also provide insights into how contextual and structural features shape identity-based mechanisms in public organizations.

5.4. Conclusions

This study prompts a reevaluation of the concept of innovation within public organizations, suggesting it should not be viewed solely as a result of structural changes or external pressures. Instead, it emerges as a more viable phenomenon when employees feel a psychological attachment and are led by figures who provide purpose, coherence, and symbolic direction. As indicated in

Table 5, the findings validate both hypotheses: organizational identification is positively linked to innovative work behavior, and this connection is strengthened under conditions of charismatic leadership. These results underscore the importance of alignment between employees’ internalized sense of belonging and the symbolic messages they receive from their leaders. While such alignment does not guarantee innovation, it fosters an environment conducive to proactive and constructive behaviors.

Notably, this study contributes to the broader field of behavioral public administration by emphasizing how psychological and relational mechanisms—such as identity, emotional resonance, and leadership symbolism—drive innovation within bureaucratic systems. By moving beyond purely structural or procedural explanations, it adds to the growing body of research that foregrounds employee cognition, motivation, and social context in shaping public sector outcomes.

Situated within the Korean public sector, this study further illustrates how national and institutional contexts can shape the operation of these mechanisms. In an environment characterized by strong hierarchies and collectivist norms, charismatic leadership may be especially potent in mobilizing organizational identification into proactive behavior. Far from limiting generalizability, the Korean case provides a theoretically meaningful boundary condition that helps explain when and why value-based leadership enhances innovation in bureaucracies.

For public agencies facing increasing complexity and accountability, this perspective implies that nurturing innovation may rely more on developing internal relational conditions than on implementing external structural reforms. Additionally, it encourages future research into how relational mechanisms—like trust, fairness, and value congruence—interact with leadership to influence employee behavior in changing institutional contexts.