Latent Profile Analysis of Depression and Its Influencing Factors Among Frail Older Adults in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Study Variables

2.3.2. Frailty

2.3.3. Depression

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

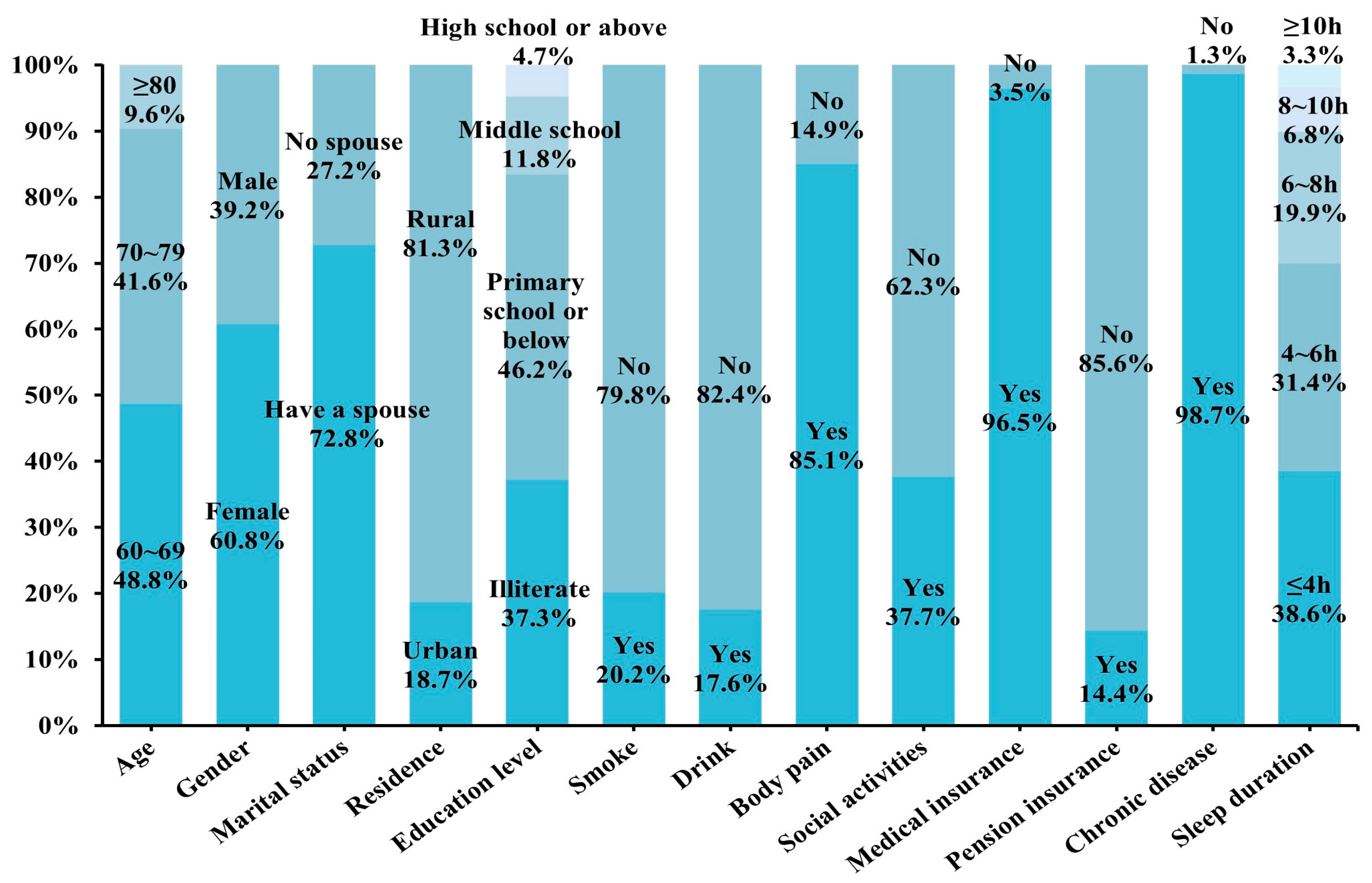

3.2. Baseline Characteristics of Frail Older Adults

3.3. Latent Profiles of Depression in Frail Older Adults

3.3.1. Latent Profile Model Fitting and Selection

3.3.2. Classification and Features of Depressive Profiles in Frail Older Adults

3.4. Univariate Analysis of Depression Profiles in Frail Older Adults

3.5. Multivariate Analysis of Depression Profiles in Frail Older Adults

3.6. Dose–Response Relationship of FI and Sleep Duration with Latent Depressive Profiles in Frail Older Adults

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Latent Depressive Profiles Among Frail Older Adults

4.2. Factors Influencing Latent Depressive Profiles Among Frail Older Adults

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Almeida, O. P., McCaul, K., Hankey, G. J., Yeap, B. B., Golledge, J., & Flicker, L. (2016). Suicide in older men: The health in men cohort study (HIMS). Preventive Medicine, 93, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balomenos, V., Ntanasi, E., Anastasiou, C. A., Charisis, S., Velonakis, G., Karavasilis, E., Tsapanou, A., Yannakoulia, M., Kosmidis, M. H., Dardiotis, E., Hadjigeorgiou, G., Sakka, P., & Scarmeas, N. (2021). Association between sleep disturbances and frailty: Evidence from a population-based study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(3), 551–558.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, J. R., Officer, A., De Carvalho, I. A., Sadana, R., Pot, A. M., Michel, J.-P., Lloyd-Sherlock, P., Epping-Jordan, J. E., Peeters, G. M. E. E. (Geeske), Mahanani, W. R., Thiyagarajan, J. A., & Chatterji, S. (2016). The World report on ageing and health: A policy framework for healthy ageing. The Lancet, 387(10033), 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bickford, D., Morin, R. T., Woodworth, C., Verduzco, E., Khan, M., Burns, E., Nelson, J. C., & Mackin, R. S. (2021). The relationship of frailty and disability with suicidal ideation in late life depression. Aging & Mental Health, 25(3), 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braver, T. S., & West, R. (2011). Working memory, executive control, and aging. In F. I. M. Craik, & T. A. Salthouse (Eds.), The handbook of aging and cognition (pp. 311–372). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bunce, D., Batterham, P. J., Mackinnon, A. J., & Christensen, H. (2012). Depression, anxiety and cognition in community-dwelling adults aged 70 years and over. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46(12), 1662–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagaloglu, H., & Yılmaz, M. (2025). Fall-related characteristics, depression and frailty levels of older adults experiencing falls in the community. British Journal of Community Nursing, 30(6), 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, K.-C., Li, Q., Jin, C., Lu, Y.-J., Cui, Z., & He, X. (2022). The influence of social and commercial pension insurance differences and social capital on the mental health of older adults—Microdata from China. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1005257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Wang, K., Zhao, J., Zhang, Z., Wang, J., & He, L. (2023). Overage labor, intergenerational financial support, and depression among older rural residents: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1219703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S. P., Vase, L., & Hooten, W. M. (2021). Chronic pain: An update on burden, best practices, and new advances. The Lancet, 397(10289), 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, L., Ananthasubramaniam, A., & Mezuk, B. (2022). Spotlight on the challenges of depression following retirement and opportunities for interventions. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 17, 1037–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J., Yu, C., Guo, Y., Bian, Z., Sun, Z., Yang, L., Chen, Y., Du, H., Li, Z., Lei, Y., Sun, D., Clarke, R., Chen, J., Chen, Z., Lv, J., & Li, L. (2020). Frailty index and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in Chinese adults: A prospective cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 5(12), e650–e660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, L. P., Tangen, C. M., Walston, J., Newman, A. B., Hirsch, C., Gottdiener, J., Seeman, T., Tracy, R., Kop, W. J., Burke, G., & McBurnie, M. A. (2001). Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56(3), M146–M157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L., Fang, M., Wang, L., Liu, L., He, C., Zhou, X., Lu, Y., & Hu, X. (2024). Gender differences in geriatric depressive symptoms in urban China: The role of ADL and sensory and communication abilities. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1344785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B., Ma, Y., Wang, C., Jiang, M., Geng, C., Chang, X., Ma, B., & Han, L. (2019). Prevalence and risk factors for frailty among community-dwelling older people in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging, 23(5), 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D., Qiu, Y., Yan, M., Zhou, T., Cheng, Z., Li, J., Wu, Q., Liu, Z., & Zhu, Y. (2023). Associations of metabolic heterogeneity of obesity with frailty progression: Results from two prospective cohorts. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle, 14(1), 632–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoogendijk, E. O., Afilalo, J., Ensrud, K. E., Kowal, P., Onder, G., & Fried, L. P. (2019). Frailty: Implications for clinical practice and public health. The Lancet, 394(10206), 1365–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T., Zhao, X., Wu, M., Li, Z., Luo, L., Yang, C., & Yang, F. (2022). Prevalence of depression in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 311, 114511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igbokwe, C. C., Ejeh, V. J., Agbaje, O. S., Umoke, P. I. C., Iweama, C. N., & Ozoemena, E. L. (2020). Prevalence of loneliness and association with depressive and anxiety symptoms among retirees in Northcentral Nigeria: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaacowitz, D. M., & Livingstone, K. M. (2014). Emotion in adulthood: What changes and why? In K. J. Reynolds, & N. R. Branscombe (Eds.), The psychology of change: Life contexts, experiences, and identities (pp. 116–132). Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, A. R., Won, C. W., Sagong, H., Bae, E., Park, H., & Yoon, J. Y. (2021). Social factors predicting improvement of frailty in community-dwelling older adults: K orean F railty and A ging C ohort S tudy. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 21(6), 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L., Wang, J., Zhu, B., Qiao, X., Jin, Y., Si, H., Wang, W., Bian, Y., & Wang, C. (2022). Expressive suppression and rumination mediate the relationship between frailty and depression among older medical inpatients. Geriatric Nursing, 43, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y., Si, H., Qiao, X., Tian, X., Liu, X., Xue, Q.-L., & Wang, C. (2020). Relationship between frailty and depression among community-dwelling older adults: The mediating and moderating role of social support. The Gerontologist, 60(8), 1466–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Jeong, H.-G., Lee, M.-S., Pae, C.-U., Patkar, A. A., Jeon, S. W., Shin, C., & Han, C. (2024). Effect of frailty on depression among patients with late-life depression: A test of anger, anxiety, and resilience as mediators. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 22(2), 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Kenyon, J., Lu, J., Sargent, L., & Kim, Y. (2025). Among 69,178 UK residents ages 65+ years, frailty associates significantly with lifestyle behaviors and depression: A cross-sectional study. Health Science Reports, 8(3), e70593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. L., Taubitz, L. E., Duke, M. W., Steuer, E. L., & Larson, C. L. (2015). State rumination enhances elaborative processing of negative material as evidenced by the late positive potential. Emotion, 15(6), 687–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J., Chen, T., He, J., Chung, R. C., Ma, H., & Tsang, H. (2022). Impacts of acupressure treatment on depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 12(1), 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., Tou, N. X., Gao, Q., Gwee, X., Wee, S. L., & Ng, T. P. (2022). Frailty and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality. PLoS ONE, 17(9), e0272527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y., Su, B., & Zheng, X. (2021). Trends and challenges for population and health during population aging—China, 2015–2050. China CDC Weekly, 3(28), 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metze, R. N., Kwekkeboom, R. H., & Abma, T. A. (2015). ‘You don’t show everyone your weakness’: Older adults’ views on using family group conferencing to regain control and autonomy. Journal of Aging Studies, 34, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Tamayo, K., Manrique-Espinoza, B., Morales-Carmona, E., & Salinas-Rodríguez, A. (2021). Sleep duration and incident frailty: The rural frailty study. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, J. E., Vellas, B., Abellan Van Kan, G., Anker, S. D., Bauer, J. M., Bernabei, R., Cesari, M., Chumlea, W. C., Doehner, W., Evans, J., Fried, L. P., Guralnik, J. M., Katz, P. R., Malmstrom, T. K., McCarter, R. J., Gutierrez Robledo, L. M., Rockwood, K., Von Haehling, S., Vandewoude, M. F., & Walston, J. (2013). Frailty consensus: A call to action. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(6), 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J. Z. (2021). Main data of the seventh national population census. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202105/t20210510_1817185.html (accessed on 7 June 2025).

- Ní Mhaoláin, A. M., Fan, C. W., Romero-Ortuno, R., Cogan, L., Cunningham, C., Kenny, R.-A., & Lawlor, B. (2012). Frailty, depression, and anxiety in later life. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(8), 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M., & Schindler, I. (2007). Changes of life satisfaction in the transition to retirement: A latent-class approach. Psychology and Aging, 22(3), 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y., Li, G., Wang, X., Liu, W., Li, X., Yang, Y., Wang, L., & Chen, L. (2024). Prevalence of multidimensional frailty among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 154, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rong, J., Ge, Y., Meng, N., Xie, T., & Ding, H. (2020). Prevalence rate of depression in Chinese elderly from 2010 to 2019: A meta-analysis. Chinese Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine, 20(1), 26–31. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Santorelli, G. D., & Ready, R. E. (2015). Alexithymia and executive function in younger and older adults. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29(7), 938–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Searle, S. D., Mitnitski, A., Gahbauer, E. A., Gill, T. M., & Rockwood, K. (2008). A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatrics, 8(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, H., Jin, Y., Qiao, X., Tian, X., Liu, X., & Wang, C. (2021). Predictive performance of 7 frailty instruments for short-term disability, falls and hospitalization among Chinese community-dwelling older adults: A prospective cohort study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 117, 103875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, P., Veronese, N., Thompson, T., Kahl, K. G., Fernandes, B. S., Prina, A. M., Solmi, M., Schofield, P., Koyanagi, A., Tseng, P.-T., Lin, P.-Y., Chu, C.-S., Cosco, T. D., Cesari, M., Carvalho, A. F., & Stubbs, B. (2017). Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 36, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H., Tyler, K., & Chan, P. (2023). Frailty status and related factors in elderly patients in intensive care for acute conditions in China. American Journal of Health Behavior, 47(2), 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, A., Ho, K. H. M., Yang, C., & Chan, H. Y. L. (2023). Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on psychological outcomes among older people with frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 140, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Dem Knesebeck, O., & Siegrist, J. (2003). Reported nonreciprocity of social exchange and depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 55(3), 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Zhu, B., Li, J., Li, X., Zhang, L., Wu, Y., & Ji, L. (2025). The moderating effect of frailty on the network of depression, anxiety, and loneliness in community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 375, 508–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., & Zhang, H. (2024). Latent profile analysis of depression and its influencing factors in older adults raising grandchildren in China. Geriatric Nursing, 59, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X., Que, J., Sun, L., Sun, T., & Yang, F. (2025). Association between urbanization levels and frailty among middle-aged and older adults in China: Evidence from the CHARLS. BMC Medicine, 23(1), 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., & Zhong, Y. (2025). The relationship between frailty and psychological functioning in community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 26(8), 105707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y., Fan, J., Lv, J., Guo, Y., Pei, P., Yang, L., Chen, Y., Du, H., Li, F., Yang, X., Avery, D., Chen, J., Chen, Z., Yu, C., Li, L., on behalf of the China Kadoorie Biobank Collaborative Group, Clarke, R., Collins, R., Peto, R., … Qu, C. (2022). Maintaining healthy sleep patterns and frailty transitions: A prospective Chinese study. BMC Medicine, 20(1), 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziółkowska, A., Wojtaszek, S., & Fels, B. (2024). Unraveling the weight of emotions: A comprehensive review of the interplay between depression and obesity. Prospects in Pharmaceutical Sciences, 22(4), 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Assignment Mode |

|---|---|

| Age | 1 = “60–69”; 2 = “70–79”; 3 = “≥80” |

| Gender | 1 = “Female”; 2 = “Male” |

| Marital status | 1 = “Have a spouse”; 2 = “No spouse” |

| Residence | 1 = “Urban”; 2 = “Rural” |

| Education level | 1 = “Illiterate”; 2 = “Primary school or below” |

| 3 = “Middle school”; 4 = “High school or above” | |

| Smoke | 1 = “Yes”; 2 = “No” |

| Drink | 1 = “Yes”; 2 = “No” |

| Body pain | 1 = “Yes”; 2 = “No” |

| Social activities | 1 = “Yes”; 2 = “No” |

| Medical insurance | 1 = “Yes”; 2 = “No” |

| Pension insurance | 1 = “Yes”; 2 = “No” |

| Chronic disease | 1 = “Yes”; 2 = “No” |

| Model | K | Likelihood | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | LMR | BLRT | Categorical Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | −17,568.224 | 35,176.449 | 35,276.198 | 35,212.674 | — | — | — | — |

| 2 | 31 | −16,634.041 | 33,330.083 | 33,484.695 | 33,386.233 | 0.891 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.452/0.548 |

| 3 | 42 | −16,221.137 | 32,526.275 | 32,735.749 | 32,602.348 | 0.906 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.281/0.340/0.380 |

| 4 | 53 | −16,025.617 | 32,157.233 | 32,421.570 | 32,253.231 | 0.956 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.075/0.207/0.334/0.384 |

| 5 | 64 | −15,894.023 | 31,916.047 | 32,235.246 | 32,031.969 | 0.934 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.033/0.176/0.247/0.247/0.296 |

| 6 | 75 | −15,757.079 | 31,664.157 | 32,038.219 | 31,800.003 | 0.930 | 0.1214 | 0.0000 | 0.077/0.095/0.152/0.202/0.219/0.255 |

| Class | Profile 1 | Profile 2 | Profile 3 | Profile 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.978 | 0.000 | 0.022 | 0.000 |

| 2 | 0.000 | 0.961 | 0.000 | 0.039 |

| 3 | 0.022 | 0.001 | 0.977 | 0.000 |

| 4 | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 0.985 |

| Variable | Low Depression–High Loneliness Group, n = 416 (38.4%) | Moderately Low Depression–High Suicidal Ideation Group, n = 81 (7.5%) | Moderately High Depression–High Negative Emotion Group, n = 362 (33.4%) | High Depression–High Suicidal Ideation Group, n = 224 (20.7%) | χ2/H | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 11.505 | 0.009 | ||||

| 60~69 | 184 (44.23%) | 36 (44.44%) | 183 (50.55%) | 125 (55.80%) | ||

| 70~79 | 176 (42.31%) | 42 (51.85%) | 149 (41.16%) | 84 (37.50%) | ||

| ≥80 | 56 (13.46%) | 3 (3.70%) | 30 (8.29%) | 15 (6.70%) | ||

| Gender | 25.932 | <0.001 | ||||

| Female | 223 (53.61%) | 54 (66.67%) | 216 (59.67%) | 165 (73.66%) | ||

| Male | 193 (46.39%) | 27 (33.33%) | 146 (40.33%) | 59 (26.34%) | ||

| Marital status | 3.841 | 0.279 | ||||

| Have a spouse | 304 (73.08%) | 60 (74.07%) | 272 (75.14%) | 152 (67.86%) | ||

| No spouse | 112 (26.92%) | 21 (25.93%) | 90 (24.86%) | 72 (32.14%) | ||

| Residence | 2.656 | 0.448 | ||||

| Urban | 85 (20.43%) | 15 (18.52%) | 68 (18.78%) | 34 (15.18%) | ||

| Rural | 331 (79.57%) | 66 (81.48%) | 294 (81.22%) | 190 (84.82%) | ||

| Education level | 5.828 | 0.120 | ||||

| Illiterate | 144 (34.62%) | 32 (39.51%) | 132 (36.46%) | 96 (42.86%) | ||

| Primary school or below | 196 (47.12%) | 33 (40.74%) | 170 (46.96%) | 101 (45.09%) | ||

| Middle school | 59 (14.18%) | 11 (13.58%) | 40 (11.05%) | 18 (8.04%) | ||

| High school or above | 17 (4.09%) | 5 (6.17%) | 20 (5.52%) | 9 (4.02%) | ||

| Smoke | 8.312 | 0.040 | ||||

| Yes | 86 (20.67%) | 12 (14.81%) | 87 (24.03%) | 34 (15.18%) | ||

| No | 330 (79.33%) | 69 (85.19%) | 275 (75.97%) | 190 (84.82%) | ||

| Drink | 5.594 | 0.133 | ||||

| Yes | 74 (17.79%) | 12 (14.81%) | 75 (20.72%) | 30 (13.39%) | ||

| No | 342 (82.21%) | 69 (85.19%) | 287 (79.28%) | 194 (86.61%) | ||

| Body pain | 15.824 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 335 (80.53%) | 68 (83.95%) | 313 (86.46%) | 206 (91.96%) | ||

| No | 81 (19.47%) | 13 (16.05%) | 49 (13.54%) | 18 (8.04%) | ||

| Social activities | 2.305 | 0.512 | ||||

| Yes | 161 (38.70%) | 35 (43.21%) | 135 (37.29%) | 77 (34.38%) | ||

| No | 225 (61.30%) | 46 (56.79%) | 227 (62.71%) | 147 (65.63%) | ||

| Medical insurance | 7.526 | 0.057 | ||||

| Yes | 396 (95.19%) | 78 (96.30%) | 357 (98.62%) | 214 (95.54%) | ||

| No | 20 (4.81%) | 3 (3.70%) | 5 (1.38%) | 10 (4.46%) | ||

| Pension insurance | 13.324 | 0.006 | ||||

| Yes | 77 (18.51%) | 11 (13.58%) | 49 (13.54%) | 19 (8.48%) | ||

| No | 339 (81.49%) | 70 (86.42%) | 313 (86.46%) | 205 (91.52%) | ||

| Chronic disease | 2.317 | 0.470 | ||||

| Yes | 411 (98.80%) | 80 (98.77%) | 355 (98.07%) | 223 (99.55%) | ||

| No | 5 (1.20%) | 1 (1.23%) | 7 (1.93%) | 1 (0.45%) | ||

| Sleep duration | 6.00 (4.00, 7.00) | 5.50 (4.00, 7.25) | 5.00 (3.38, 7.00) | 4.25 (3.00, 6.00) | 28.742 | <0.001 |

| Frailty index | 31.25 (27.59, 37.50) | 33.48 (28.13, 39.90) | 33.15 (27.65, 39.76) | 33.98 (28.13, 43.72) | 12.550 | 0.006 |

| Variable | β | Wald χ2 | OR | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Depression–High Loneliness Group | 0.977 | 6.951 | 2.656 | 1.285~5.490 | 0.008 |

| Moderately Low Depression–High Suicidal Ideation Group | 1.302 | 12.293 | 3.677 | 1.775~7.614 | <0.001 |

| Moderately High Depression–High Negative Emotion Group | 2.899 | 58.226 | 18.156 | 8.628~38.245 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||

| 60~69 | 0.609 | 8.605 | 1.839 | 1.224~2.759 | 0.003 |

| 70~79 | 0.365 | 3.036 | 1.441 | 0.955~2.173 | 0.081 |

| ≥80 | — | — | — | — | — |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 0.374 | 7.926 | 1.454 | 1.121~1.885 | 0.005 |

| Male | — | — | — | — | — |

| Smoke | |||||

| Yes | 0.082 | 0.281 | 1.085 | 0.801~1.473 | 0.596 |

| No | — | — | — | — | — |

| Body pain | |||||

| Yes | 0.388 | 5.314 | 1.474 | 1.060~2.048 | 0.021 |

| No | — | — | — | — | — |

| Pension insurance | |||||

| Yes | −0.392 | 5.417 | 0.676 | 0.486~−0.940 | 0.020 |

| No | — | — | — | — | — |

| Sleep duration | −0.090 | 14.885 | 0.914 | 0.874~−0.957 | <0.001 |

| Frailty index | 0.028 | 22.707 | 1.028 | 1.017~1.041 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, L.; Fan, P.; Zhang, S.; Rong, C. Latent Profile Analysis of Depression and Its Influencing Factors Among Frail Older Adults in China. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091217

Ye L, Fan P, Zhang S, Rong C. Latent Profile Analysis of Depression and Its Influencing Factors Among Frail Older Adults in China. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091217

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Lingling, Penghao Fan, Siyuan Zhang, and Chao Rong. 2025. "Latent Profile Analysis of Depression and Its Influencing Factors Among Frail Older Adults in China" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091217

APA StyleYe, L., Fan, P., Zhang, S., & Rong, C. (2025). Latent Profile Analysis of Depression and Its Influencing Factors Among Frail Older Adults in China. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1217. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091217