Psychosocial Risk Factors and Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming (PIG): The Mediating Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Hedonic Gaming Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Internet Gaming Addiction: A Global Health Concern Affecting Adolescents

1.2. Shift in Focus: From Addiction to Problematic Use

1.3. Psychosocial Risk Factors, Social Adaptation, and Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming

1.4. Deviant Peer Affiliation and Hedonic Gaming Experience: The Mediating Factors

1.5. Research Aims, Research Significance, and Research Questions (RQs)

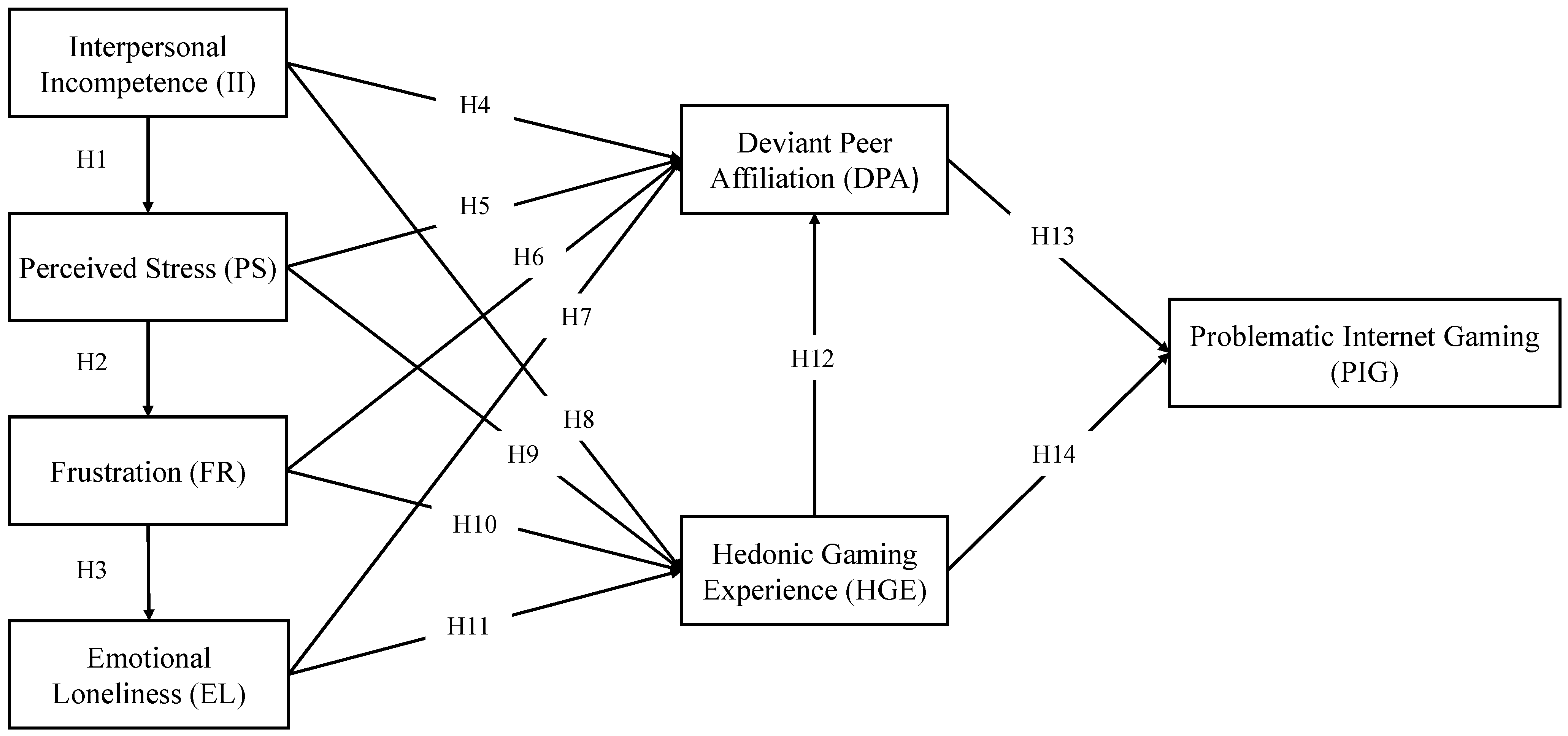

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. The Sequential Influence of Interpersonal Incompetence (II), Perceived Stress, Frustration (FR), and Emotional Loneliness (EL)

2.2. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Deviant Peer Affiliation (DPA)

2.3. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Hedonic Gaming Experience (HGE)

2.4. Deviant Peer Affiliation, Hedonic Gaming Experience, and Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming

3. Methods

3.1. Research Instruments

3.2. Data Collection, Participants, and Ethics Considerations

3.3. Data Analysis

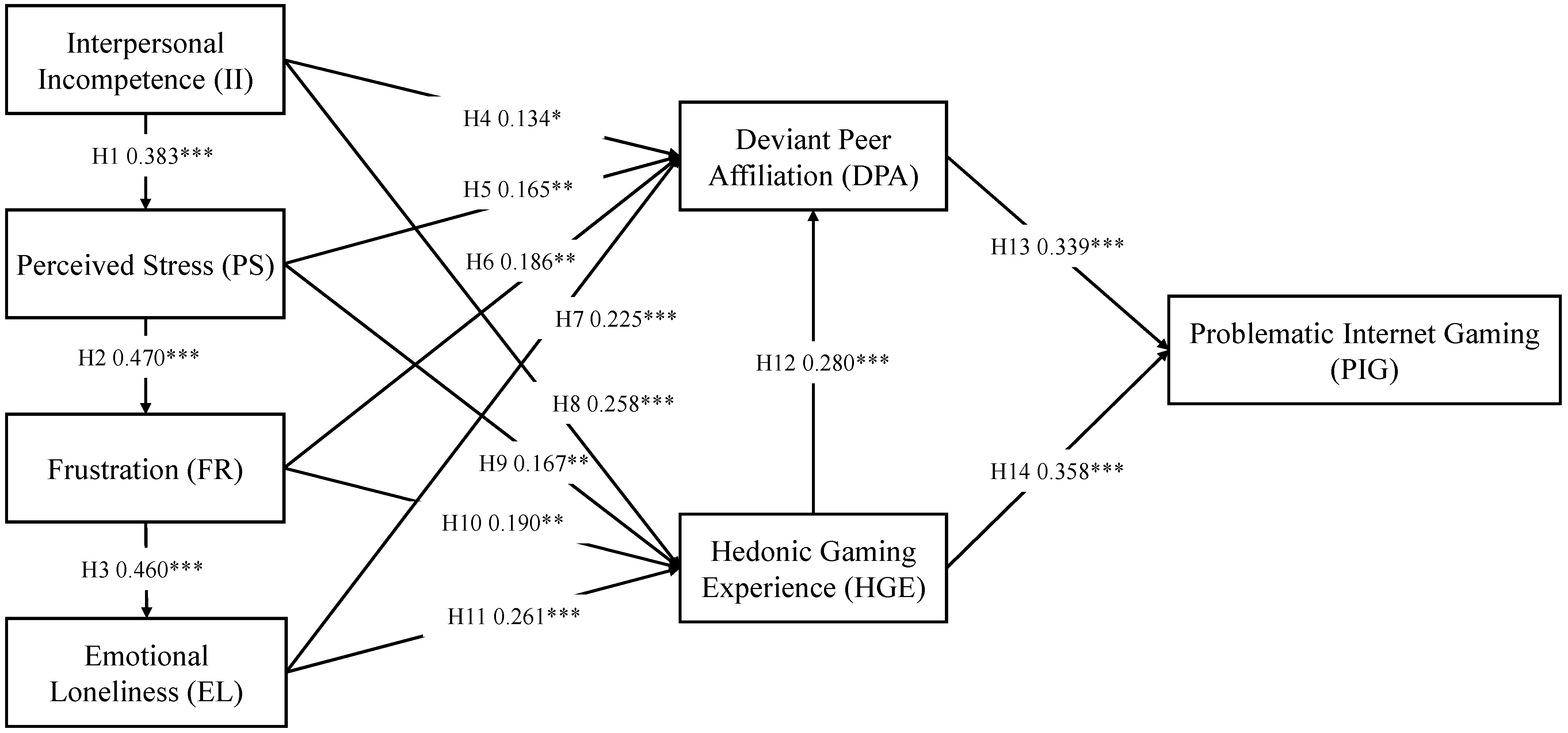

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Model Fit and Hypothesis Testing

4.3. Prediction Power of the Variables in the Study

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary

6.2. Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| II | Interpersonal incompetence |

| PS | Perceived stress |

| FR | Frustration |

| EL | Emotional loneliness |

| DPA | Deviant peer affiliation |

| HGE | Hedonic gaming experience |

| PIG | Problematic Internet gaming |

References

- Allen, J. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2018). Satisfaction and frustration of basic psychological needs in the real world and in video games predict internet gaming disorder scores and well-being. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baysak, E., Yertutanol, F. D. K., Dalgar, I., & Candansayar, S. (2018). How game addiction rates and related psychosocial risk factors change within 2-years: A follow-up study. Psychiatry Investigation, 15(10), 984–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S., Jeong, E. J., & Kim, D. J. (2019). The role of individuals’ need for online social interactions and interpersonal incompetence in digital game addiction. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 36(5), 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billieux, J., Van der Linden, M., Achab, S., Khazaal, Y., Paraskevopoulos, L., Zullino, D., & Thorens, G. (2013). Why do you play World of Warcraft? An in-depth exploration of self-reported motivations to play online and in-game behaviours in the virtual world of Azeroth. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(1), 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinka, L., & Mikuška, J. (2014). The role of social motivation and sociability of gamers in online game addiction. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 8(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, S., Williams, D., & Yee, N. (2009). Problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being among MMO players. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(6), 1312–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, I. C., Liu, C.-C., & Chen, K. (2014). The effects of hedonic/utilitarian expectations and social influence on continuance intention to play online games. Internet Research, 24(1), 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., & Choi, Y. (2025). The influence of social distance perception among gamers on relationships between game motivation and interpersonal competency. Entertainment Computing, 52, 100903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, H., Sim, T., Liau, A. K., Gentile, D. A., & Khoo, A. (2015). Parental influences on pathological symptoms of video-gaming among children and adolescents: A prospective study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiTommaso, E., Brannen, C., & Best, L. A. (2004). Measurement and validity characteristics of the short version of the social and emotional loneliness scale for adults. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 64(1), 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergusson, D. M., Swain-Campbell, N. R., & Horwood, L. J. (2002). Deviant peer affiliations, crime and substance use: A fixed effects regression analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorilli, C., Grimaldi Capitello, T., Barni, D., Buonomo, I., & Gentile, S. (2019). Predicting adolescent depression: The interrelated roles of self-esteem and interpersonal stressors. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Hult, T., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Härdle, W. K., Okhrin, O., & Okhrin, Y. (2017). Multivariate statistical analysis. In Basic elements of computational statistics (pp. 219–241). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Z., Griffiths, M. D., & Baguley, T. (2012). Online gaming addiction: Classification, prediction and associated risk factors. Addiction Research & Theory, 20(5), 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, L. D., & Drazkowski, D. (2014). MMORPG escapism predicts decreased well-being: Examination of gaming time, game realism beliefs, and online social support for offline problems. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 17(5), 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosa, M., & Uysal, A. (2021). Need frustration in online video games. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(11), 2415–2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Internet gaming addiction: A systematic review of empirical research. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 10, 278–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L. T. (2014). Risk factors of Internet addiction and the health effect of internet addiction on adolescents: A systematic review of longitudinal and prospective studies. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-y., Ko, D. W., & Lee, H. (2019). Loneliness, regulatory focus, inter-personal competence, and online game addiction: A moderated mediation model. Internet Research, 29(2), 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Z. W. Y., Cheung, C. M. K., & Chan, T. K. H. (2020). Understanding massively multiplayer online role—Playing game addiction: A hedonic management perspective. Information Systems Journal, 31(1), 33–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2009). Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychology, 12(1), 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmens, J. S., Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2011). Psychosocial causes and consequences of pathological gaming. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Peng, K., Wu, Y., Wang, L., & Luo, Z. (2025). Investigating parental factors that lead to adolescent Internet Gaming Addiction (IGA). PLoS ONE, 20(4), e0322117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Zhao, F., & Yu, G. (2022). Childhood emotional abuse and depression among adolescents: Roles of deviant peer affiliation and gender. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(1–2), NP830–NP850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., & Li, H. (2011). Exploring the impact of use context on mobile hedonic services adoption: An empirical study on mobile gaming in China. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(2), 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z. (2021). Gamification for educational purposes: What are the factors contributing to varied effectiveness? Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 891–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z., & Xie, J. (2025). The development and validation of the adolescent problematic gaming scale (PGS-Adolescent). Behavioral Sciences, 15(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N. F., Ab Manan, N., Muhammad Firdaus Chan, M. F., Rahmatullah, B., Abd Wahab, R., Baharudin, S. N. A., Govindasamy, P., & Abdulla, K. (2023). The prevalence of internet gaming disorders and the associated psychosocial risk factors among adolescents in Malaysian secondary schools. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 28(4), 1420–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrug, S., Molina, B. S., Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Hechtman, L., & Arnold, L. E. (2012). Peer rejection and friendships in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Contributions to long-term outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(6), 1013–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pera, A. (2020). The psychology of addictive smartphone behavior in young adults: Problematic use, social anxiety, and depressive stress. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 573473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porat, S.-l., Reznik, A., Masuyama, A., Sugawara, D., Sternberg, G. G., Kubo, T., & Isralowitz, R. (2025). Psycho-Emotional factors associated with internet gaming disorder among Japanese and Israeli university students and other young adults. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puiras, E., Cummings, S., & Mazmanian, D. (2020). Playing to escape: Examining escapism in gamblers and gamers. Journal of Gambling Issues. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purwaningsih, E., & Nurmala, I. (2021). The impact of online game addiction on adolescent mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Access Macedonian Journal of Medical Sciences (OAMJMS), 9(F), 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszkowska, A., Gąsior, T., Stefanek, F., & Stenseng, F. (2025). SPACE to esc: Affective and motivational correlates to adaptive and maladaptive escapism among video gamers—A network analysis. Psychology of Popular Media. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X. (2007). Multivariate data analysis. Technometrics, 49(1), 103–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, M. J., Lee, H., Lee, T.-H., Cho, H., Jung, D. J., Kim, D.-J., & Choi, I. Y. (2018). Risk factors for internet gaming disorder: Psychological factors and internet gaming characteristics. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saricali, M., & Guler, D. (2022). The mediating role of psychological need frustration on the relationship between frustration intolerance and existential loneliness. Current Psychology, 41(8), 5603–5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherer, M., Maddux, J. E., Mercandante, B., Prentice-Dunn, S., Jacobs, B., & Rogers, R. W. (1982). The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports, 51(2), 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkute, D., Tarailis, P., Pipinis, E., & Griskova-Bulanova, I. (2025). Assessing the spectrum of internet use in a healthy sample: Altered psychological states and intact brain responses to an equiprobable Go/NoGo task. Behavioral Sciences, 15(5), 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioni, S. R., Burleson, M. H., & Bekerian, D. A. (2017). Internet gaming disorder: Social phobia and identifying with your virtual self. Computers in Human Behavior, 71, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Yu, C., Zhang, W., Chen, Y., Zhu, J., & Liu, Q. (2017). School climate and adolescent aggression: A moderated mediation model involving deviant peer affiliation and sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yayla, İ. E., Dombak, K., Diril, S., Düşünceli, B., Çelik, E., & Yildirim, M. (2025). Difficulties in emotion regulation as a mediator and gender as a moderator in the relationship between problematic digital gaming and life satisfaction among adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, J. Y., Ko, C. H., Yen, C. F., Chen, S. H., Chung, W. L., & Chen, C. C. (2008). Psychiatric symptoms in adolescents with internet addiction: Comparison with substance use. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 62(1), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, V., & Tunca, B. (2024). Structural model proposal to explain online game addiction. Entertainment Computing, 48, 100611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajac, K., Ginley, M. K., Chang, R., & Petry, N. M. (2017). Treatments for internet gaming disorder and internet addiction: A systematic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(8), 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajenkowska, A., Jasielska, D., & Melonowska, J. (2017). Stress and sensitivity to frustration predicting depression among young adults in poland and korea—Psychological and philosophical explanations. Current Psychology, 38(3), 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Yu, C., Bao, Z., Jiang, Y., Zhang, W., Chen, Y., Qiu, B., & Zhang, J. (2017). Deviant peer affiliation as an explanatory mechanism in the association between corporal punishment and physical aggression: A longitudinal study among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 1537–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Zhang, W., Yu, C., & Bao, Z. (2015). Early adolescent Internet game addiction in context: How parents, school, and peers impact youth. Computers in Human Behavior, 50, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item Code | Factor/Factor Loadings | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

| Interpersonal Incompetence (II) | II1 | 0.823 | ||||||

| II2 | 0.727 | |||||||

| II3 | 0.698 | |||||||

| II4 | 0.761 | |||||||

| II5 | 0.822 | |||||||

| Perceived Stress (PS) | PS1 | 0.676 | ||||||

| PS2 | 0.717 | |||||||

| PS3 | 0.756 | |||||||

| PS4 | 0.724 | |||||||

| PS5 | 0.684 | |||||||

| Frustration (FR) | FR1 | 0.682 | ||||||

| FR2 | 0.794 | |||||||

| FR3 | 0.728 | |||||||

| FR4 | 0.776 | |||||||

| FR5 | 0.701 | |||||||

| Emotional Loneliness (EL) | EL1 | −0.611 | ||||||

| EL2 | −0.661 | |||||||

| EL3 | −0.688 | |||||||

| EL4 | −0.667 | |||||||

| EL5 | −0.836 | |||||||

| Deviant Peer Affiliation (DPA) | DPA1 | 0.578 | ||||||

| DPA2 | 0.619 | |||||||

| DPA3 | 0.600 | |||||||

| DPA4 | 0.784 | |||||||

| DPA5 | 0.541 | |||||||

| DPA6 | 0.627 | |||||||

| DPA7 | 0.772 | |||||||

| DPA8 | 0.646 | |||||||

| Hedonic Gaming Experience (HGE) | HGE1 | 0.690 | ||||||

| HGE2 | 0.780 | |||||||

| HGE3 | 0.522 | |||||||

| HGE4 | 0.765 | |||||||

| HGE5 | 0.542 | |||||||

| Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming (PIG) | PIG1 | 0.724 | ||||||

| PIG2 | 0.800 | |||||||

| PIG3 | 0.802 | |||||||

| PIG4 | 0.757 | |||||||

| PIG5 | 0.729 | |||||||

| Cronbach’s Alpha (α): | 0.929 | 0.901 | 0.877 | 0.872 | 0.883 | 0.890 | 0.897 | |

| AVE (Average Variance Extracted): | 0.424 | 0.590 | 0.544 | 0.507 | 0.447 | 0.485 | 0.582 | |

| CR (Composite Reliability): | 0.853 | 0.877 | 0.856 | 0.837 | 0.797 | 0.823 | 0.874 | |

| Construct | AVE | II | PS | FR | EL | DPA | HGE | API |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Incompetence (II) | 0.590 | 0.768 | ||||||

| Perceived Stress (PS) | 0.507 | 0.430 ** | 0.712 | |||||

| Frustration (FR) | 0.544 | 0.216 ** | 0.489 ** | 0.738 | ||||

| Emotional Loneliness (EL) | 0.485 | 0.506 ** | 0.505 ** | 0.495 ** | 0.696 | |||

| Deviant Peer Affiliation (DPA) | 0.424 | 0.522 ** | 0.582 ** | 0.533 ** | 0.647 | 0.651 | ||

| Hedonic Gaming Experience (HGE) | 0.447 | 0.490 ** | 0.500 ** | 0.470 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.630 ** | 0.669 | |

| Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming (PIG) | 0.582 | 0.226 ** | 0.314 ** | 0.403 ** | 0.307 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.560 ** | 0.763 |

| Code | Path | O | T-Value | p-Value | Hypothesis | Result | Hypothesis-Testing Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | II → PS | 0.383 | 6.631 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H2 | PS → FR | 0.470 | 8.236 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H3 | FR → EL | 0.460 | 8.569 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H4 | II → DPA | 0.134 | 2.590 | * | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H5 | PS → DPA | 0.165 | 2.804 | ** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H6 | FR → DPA | 0.186 | 2.962 | ** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H7 | EL → DPA | 0.225 | 3.533 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H8 | II → HGE | 0.258 | 4.143 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H9 | PS → HGE | 0.167 | 2.634 | ** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H10 | FR → HGE | 0.190 | 2.850 | ** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H11 | EL → HGE | 0.261 | 3.661 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H12 | HGE → DPA | 0.280 | 4.675 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H13 | DPA → PIG | 0.339 | 5.177 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

| H14 | HGE → PIG | 0.358 | 5.193 | *** | Positive | Positive | Confirmed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, Y.; Li, H.; Luo, Z. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming (PIG): The Mediating Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Hedonic Gaming Experience. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091177

Wu Y, Li H, Luo Z. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming (PIG): The Mediating Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Hedonic Gaming Experience. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091177

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Yi, Huazhen Li, and Zhanni Luo. 2025. "Psychosocial Risk Factors and Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming (PIG): The Mediating Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Hedonic Gaming Experience" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091177

APA StyleWu, Y., Li, H., & Luo, Z. (2025). Psychosocial Risk Factors and Adolescent Problematic Internet Gaming (PIG): The Mediating Roles of Deviant Peer Affiliation and Hedonic Gaming Experience. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1177. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091177