5.1. Summary of Main Findings

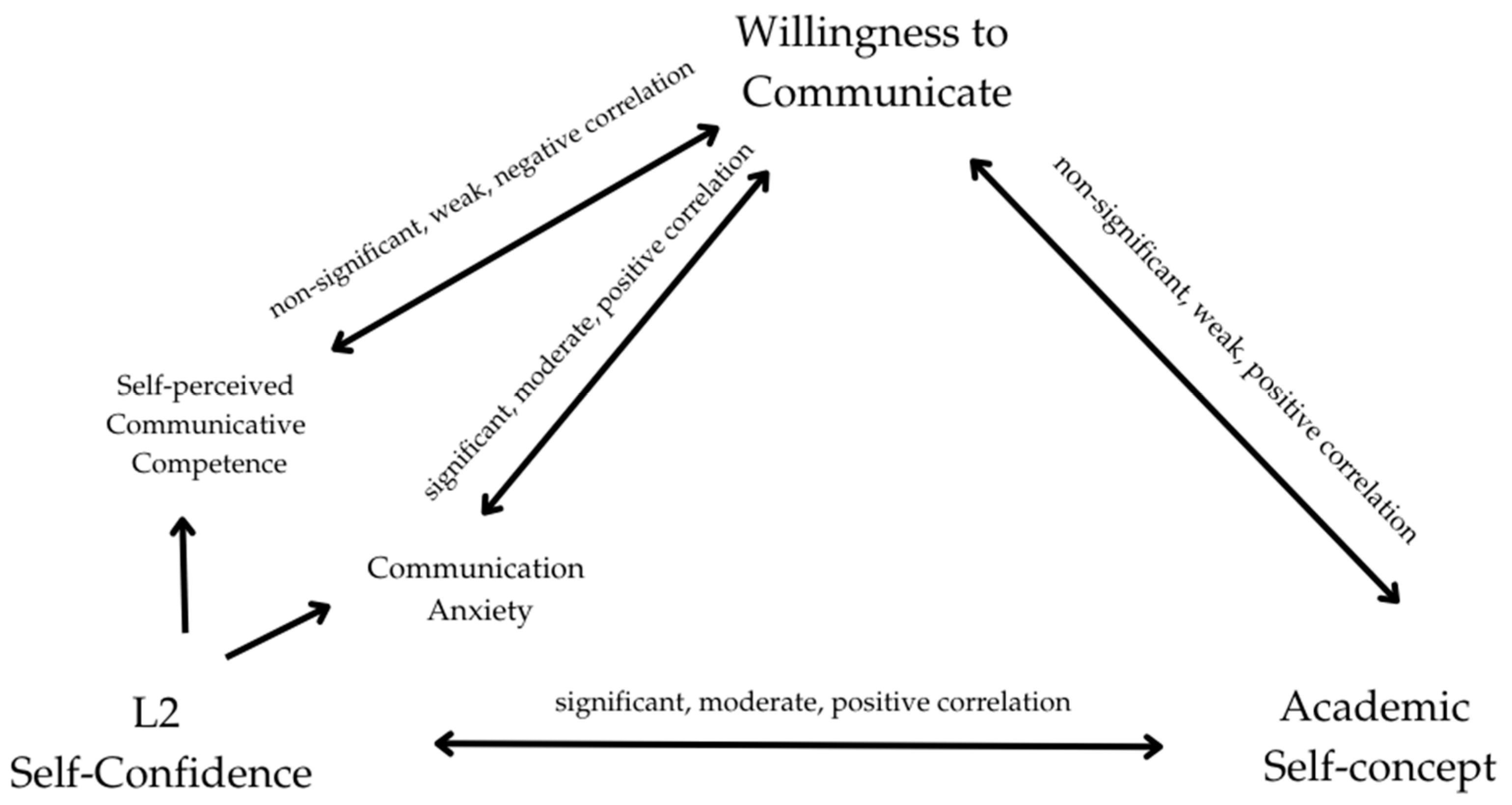

This study investigated the interrelationship among WTC, L2 self-confidence, and academic self-concept in Vietnamese university students studying in the United Kingdom, employing an explanatory sequential mixed-methods design. The quantitative findings revealed that participants generally reported moderate levels of WTC and L2 self-confidence, and a fair but somewhat variable academic self-concept. Significant positive correlations were identified between WTC and L2 self-confidence, and between L2 self-confidence and academic self-concept, while the association between WTC and academic self-concept was positive but weak and not statistically significant.

Qualitative insights further contextualized these results. Students perceived an enhancement in their willingness to communicate in supportive and familiar environments, especially when engaging with friends or acquaintances, and were often motivated by desires for cultural exchange and information sharing. L2 self-confidence was found to be dynamic: shaped by cumulative learning experiences, supportive classroom climates, and evolving personal mindsets toward communication anxiety and mistake-making. While most participants viewed themselves as competent and resilient in daily interactions, many reported persistent anxiety in formal or high-stakes situations, particularly when required to use academic language or present in public. Academic self-concept, though generally positive, was susceptible to fluctuations due to self-comparison and cultural expectations, especially when interacting with peers from similar backgrounds.

Overall, the findings indicate that L2 self-confidence plays a pivotal mediating role, linking learners’ internal self-concept to their observable communication behaviours. The results also highlight the influence of social context, personal agency, and cultural factors on the communication patterns of international students in English-medium academic environments.

5.2. Contextualising the Results Within Current Scholarship

The findings of this study both reinforce and extend existing understandings of WTC, L2 self-confidence, and academic self-concept within the field of second language acquisition and behavioural science. Taken together, the results offer several important insights into how psychological and contextual variables interact to shape the communicative behaviour of international students in multicultural academic settings. However, consideration should be made as there is a lack of direct factor measurement and observation in the current study, which should be treated perception-wise only.

The moderate levels of WTC reported align with previous research highlighting the importance of supportive and immersive environments in fostering communication (

Ghonsooly et al., 2014;

Katiandagho & Sengkey, 2022). While earlier studies in Asian EFL contexts have sometimes emphasized passivity, reticence, or “face-protective” behaviour among Asian learners (

Tam, 2022), the current study demonstrates that immersion in an English-speaking environment and the necessity of using English for academic and social survival appear to outweigh many traditional cultural inhibitions. Students reported a willingness to communicate, particularly in small-group or familiar contexts, which echoes the findings of

Ducker (

2021) regarding the influence of group dynamics and social safety on WTC. Notably, even where apprehensions about negative evaluation or “being judged” persisted, especially in interactions with other Vietnamese students, these factors rarely resulted in avoidance or communicative withdrawal. This suggests an emerging resilience and adaptability among international learners, potentially fostered by exposure to diverse intercultural interactions and a shifting mindset towards language learning (

Lou & Noels, 2020).

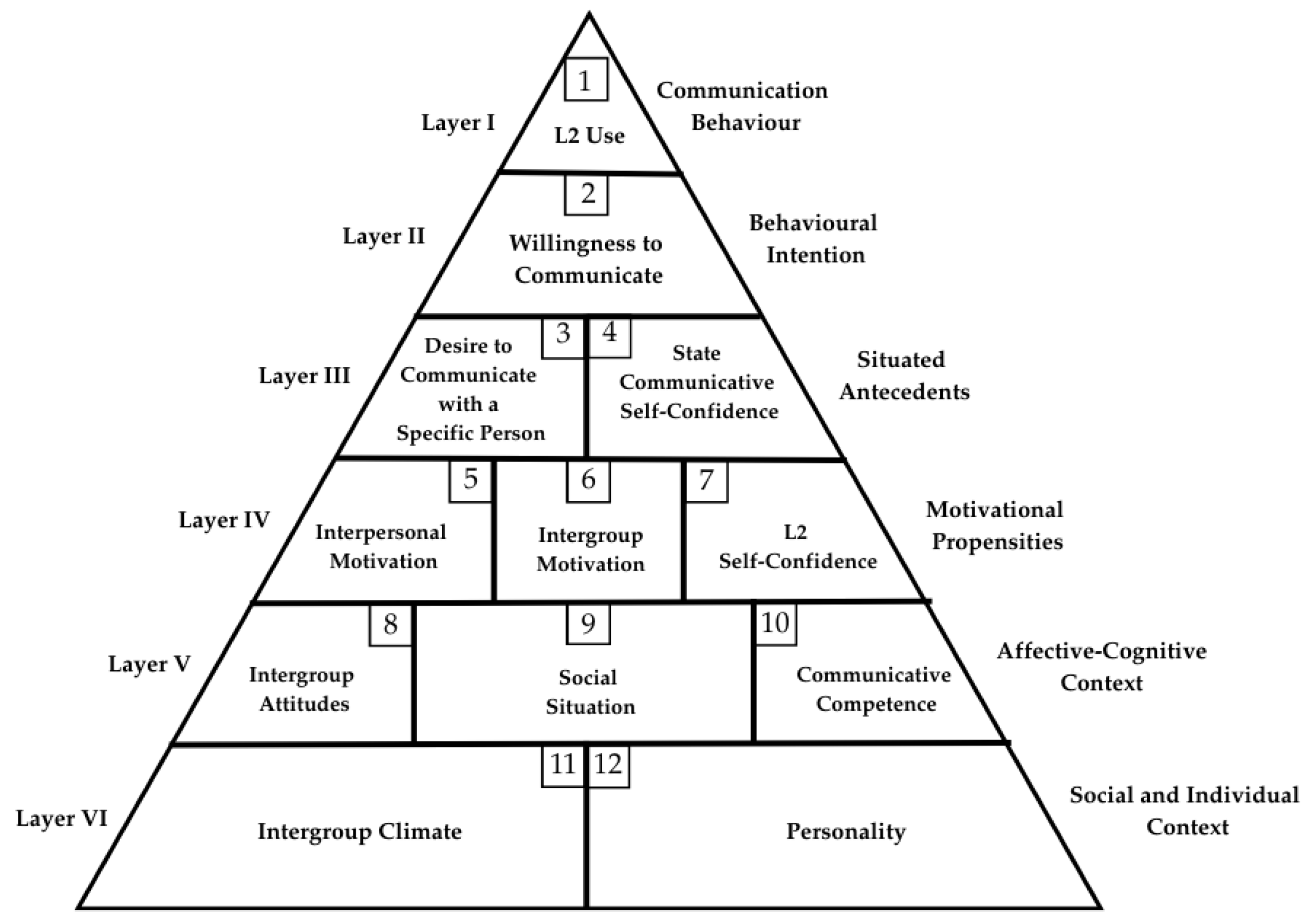

The dynamic nature of L2 self-confidence observed in this study resonates with the heuristic model proposed by

D. MacIntyre et al. (

1998), where self-confidence is conceptualized as a composite of self-perceived communicative competence and communication anxiety. Consistent with

Ghonsooly et al. (

2014),

Fernando (

2022), and

Yashima (

2002), participants in this study identified supportive classroom climates and positive interpersonal experiences as critical contributors to their self-confidence, particularly in informal contexts. The persistence of anxiety in formal or evaluative settings, such as presentations, underscores the enduring impact of situational variables on communicative behaviour. However, the willingness of students to reinterpret anxiety and mistake-making as natural and constructive elements of the learning process reflects a positive orientation toward language development: an orientation that may be linked to academic mindsets emphasising growth, resilience, and self-efficacy (

Mercer, 2011). Notably, participants in this study did not report the debilitating self-doubt sometimes found in other samples (e.g.,

Zhao & Chang, 2022), suggesting that contextual and institutional factors, such as inclusive teaching practices and peer support, may mitigate the negative effects of communication anxiety.

Academic self-concept emerged in this study as a nuanced, contextually responsive construct. While self-comparison and cultural expectations introduced elements of instability and vulnerability, most participants demonstrated awareness of these influences and reframed them as sources of motivation rather than impediments. This aligns with previous work by

Pattapong (

2015), who emphasized the role of self-comparison in shaping learners’ academic identities and behavioural choices. The practice of “saving face” and striving for humility, often associated with Confucian-influenced educational cultures (

Leung, 1998;

Phuong-Mai, 2008), was present, but was typically balanced by a proactive and agentic stance toward language use and self-improvement. Interestingly, the findings indicate that academic self-concept, while influential, does not operate as a fixed personality trait but as a flexible and dynamic self-presentation shaped by the desire to communicate and succeed in new cultural contexts.

The interrelationships among WTC, L2 self-confidence, and academic self-concept reported in this study lend empirical support to the theoretical proposition that self-confidence mediates the influence of academic self-concept on communicative behaviour (

D. MacIntyre et al., 1998;

Mercer, 2011;

Lubis et al., 2022). Quantitative analysis demonstrated that L2 self-confidence is a significant predictor of WTC, corroborating the work of

Fatima et al. (

2020) and

Peng and Woodrow (

2010). The moderate association between academic self-concept and L2 self-confidence further reinforces the idea that learners’ beliefs about their academic abilities underpin their communicative self-assurance, particularly in challenging or high-stakes environments. The positive, albeit non-significant, relationship between academic self-concept and WTC may reflect the complex and sometimes competing pressures faced by international students: while positive self-concept encourages engagement, ongoing self-comparison and cultural adaptation processes may introduce hesitation or fluctuation in communicative behaviours.

From a broader behavioural science perspective, the findings illustrate how psychosocial variables, such as perceived competence, anxiety, and self-concept, are not merely internal states but are dynamically co-constructed in relation to social context, cultural identity, and learning environment (

Basarkod et al., 2024;

Zhou et al., 2025). The nuanced interplay among these constructs in this cohort of Vietnamese students underscores the need for a holistic, context-sensitive approach to understanding language learning behaviour in multicultural higher education. These results not only affirm key tenets of the WTC and self-concept models but also highlight the importance of resilience, agency, and adaptability in the academic and social success of international learners.

5.3. Implications for International Language Education

The findings of this study offer several important implications for both theory and practice in the fields of second language acquisition, behavioural science, and international education.

This research advances the theoretical understanding of L2 communication by confirming and extending the heuristic model of WTC (

D. MacIntyre et al., 1998) and related frameworks (

Mercer, 2011;

Bandura, 1986). It substantiates the role of L2 self-confidence as a central mediator between academic self-concept and communication behaviour and demonstrates that self-perceptions are not static personality traits, but dynamic constructs shaped by context, social interaction, and cultural adaptation. The finding that academic self-concept does not directly predict WTC, but operates in conjunction with self-confidence, refines our understanding of motivational and affective variables in L2 engagement. Moreover, the observed flexibility and agentic self-positioning among Vietnamese students in the UK points to the importance of viewing communicative behaviour as both context-sensitive and influenced by evolving self-beliefs. This holistic perspective enriches existing models by foregrounding the interplay of psychological, cultural, and situational variables in multilingual academic environments.

The study also yields actionable recommendations for educators, university administrators, and support professionals working with international and culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) students. For educators, the results underscore the value of creating supportive, inclusive classroom environments that encourage risk-taking and foster communicative confidence. Strategies such as collaborative group work, peer mentoring, and positive feedback can help reduce communication anxiety and promote a growth mindset (

Springer et al., 2025). Recognising that self-confidence and self-concept are malleable (

Van der Aar et al., 2022), instructors should explicitly address these constructs through reflective activities, opportunities for safe practice, and discussions that normalise anxiety and mistake-making as part of the learning process.

For institutional policy and student support services, the findings highlight the need for targeted interventions that address the psychosocial as well as linguistic needs of international students. Orientation programs, counselling, and language support services should be designed to help students navigate cultural adjustment, manage self-comparison, and build resilience (

Sakız & Jencius, 2024). Providing opportunities for meaningful intercultural interaction, both within and beyond the classroom, may further enhance willingness to communicate and academic self-concept (

D’Orazzi & Marangell, 2025;

Vromans et al., 2023).

From a clinical perspective, the study’s behavioural framing of communication, self-confidence, and self-concept may inform the design of support programs for students experiencing language-related anxiety or social withdrawal (

Beesdo et al., 2009;

Wilmot et al., 2024;

Zhang & Zhang, 2022). Clinicians working with CALD or international students should assess not only linguistic proficiency but also underlying psychosocial variables (

Khawaja & Wotherspoon, 2022), therefore, offering interventions that build communicative self-assurance and address anxiety in high-stakes or unfamiliar settings. In this sense, these findings also have broader implications for students from CALD backgrounds, particularly in relation to the acquisition and use of second language forms (as opposed to content or use; see

Bloom & Lahey, 1978), e.g., morpho-syntax between typologically different L1s and L2s (e.g.,

Furukawa & Nakamura, 2024;

Han, 2013;

Han & Shi, 2016;

Hwang & Steinhauer, 2011), where self-confidence and academic self-concept can significantly influence learners’ willingness to take communicative risks and experiment with more complex grammatical forms in authentic settings.

In summary, this research highlights the interdependence of psychological, behavioural, and contextual factors in shaping L2 communication. By adopting a holistic and context-sensitive approach, educators and support professionals can more effectively foster communicative engagement, confidence, and well-being among international students in higher education.

5.4. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the interplay between willingness to communicate, L2 self-confidence, and academic self-concept among Vietnamese university students in the United Kingdom, several limitations should be acknowledged. These constraints offer important context for interpreting the findings and highlight avenues for future research.

The relatively small sample size and the focus on students from a single university limit the generalisability of the results. The small scale of the qualitative sample, for example, can narrow down the study’s applicability. Also, the single-university setting created a unique profile that yielded desirable bias for replication. Although the mixed-methods approach allowed for in-depth exploration and triangulation of constructs, larger and more diverse samples, including students from multiple institutions, degree programs, and countries, would provide a broader basis for understanding these phenomena across different cultural and academic contexts.

Consequently, the study’s findings are embedded in the specific cultural, linguistic, and institutional context of Vietnamese students studying in the UK. Communication behaviours, self-confidence, and academic self-concept are influenced by a range of cultural and contextual variables, including prior language experiences, exposure to English, and institutional support structures. Replicating and extending this research among other international student groups, as well as in different host countries or educational settings, would allow for meaningful cross-cultural comparison and deepen our understanding of context-sensitive behavioural dynamics.

Further, the reliance on self-report questionnaires and semi-structured interviews may introduce bias, such as social desirability effects or recall bias. While the combination of quantitative and qualitative data strengthens the study, future research could benefit from incorporating additional methods such as classroom observation, behavioural tracking, or longitudinal designs. For example, following students across time points would shed light on how willingness to communicate, self-confidence, and academic self-concept evolve in response to new challenges, achievements, and social interactions.

While this study focused on the interrelationships among three core constructs, additional variables such as motivation, language proficiency, social network size, or perceived support were not systematically examined. Future research could explore how these and other factors interact with WTC, self-confidence, and academic self-concept, potentially revealing more complex or indirect pathways influencing language behaviour. Additionally, future work should seek to design, implement, and assess targeted interventions, such as workshops on communication confidence, peer mentoring schemes, or culturally responsive counselling, to determine their impact on students’ behavioural engagement and well-being.

While acknowledging its limitations, this study contributes to a growing evidence base on the behavioural and psychological determinants of communicative success among international learners. Addressing the above constraints in future research will help to refine theoretical models, inform context-sensitive practice, and support the academic and social integration of culturally and linguistically diverse students in higher education.