The Impact of Humble Leadership on the Green Innovation Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Humble Leadership and Green Innovation Performance

2.3. Humble Leadership and an Organizational Caring Ethical Climate

2.4. Mediating Role of a Caring Ethical Climate

2.5. Moderating Role of Organizational Structure

2.6. Moderating Role of Organizational Resource Slack

3. Research Method

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Convergent Validity

4.3. Discriminant Validity

4.4. Correlation Analysis

4.5. Test of Mediation Effect

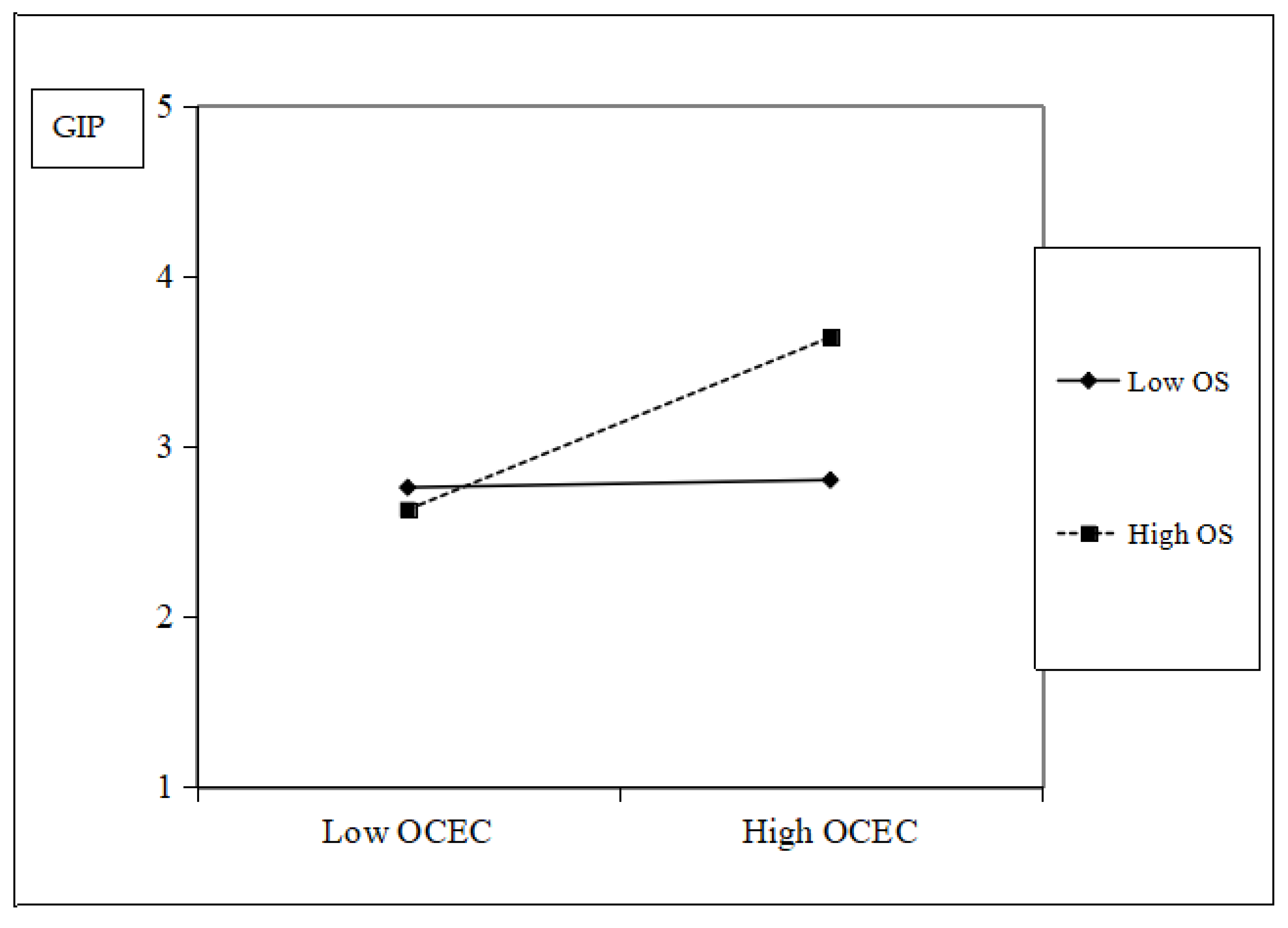

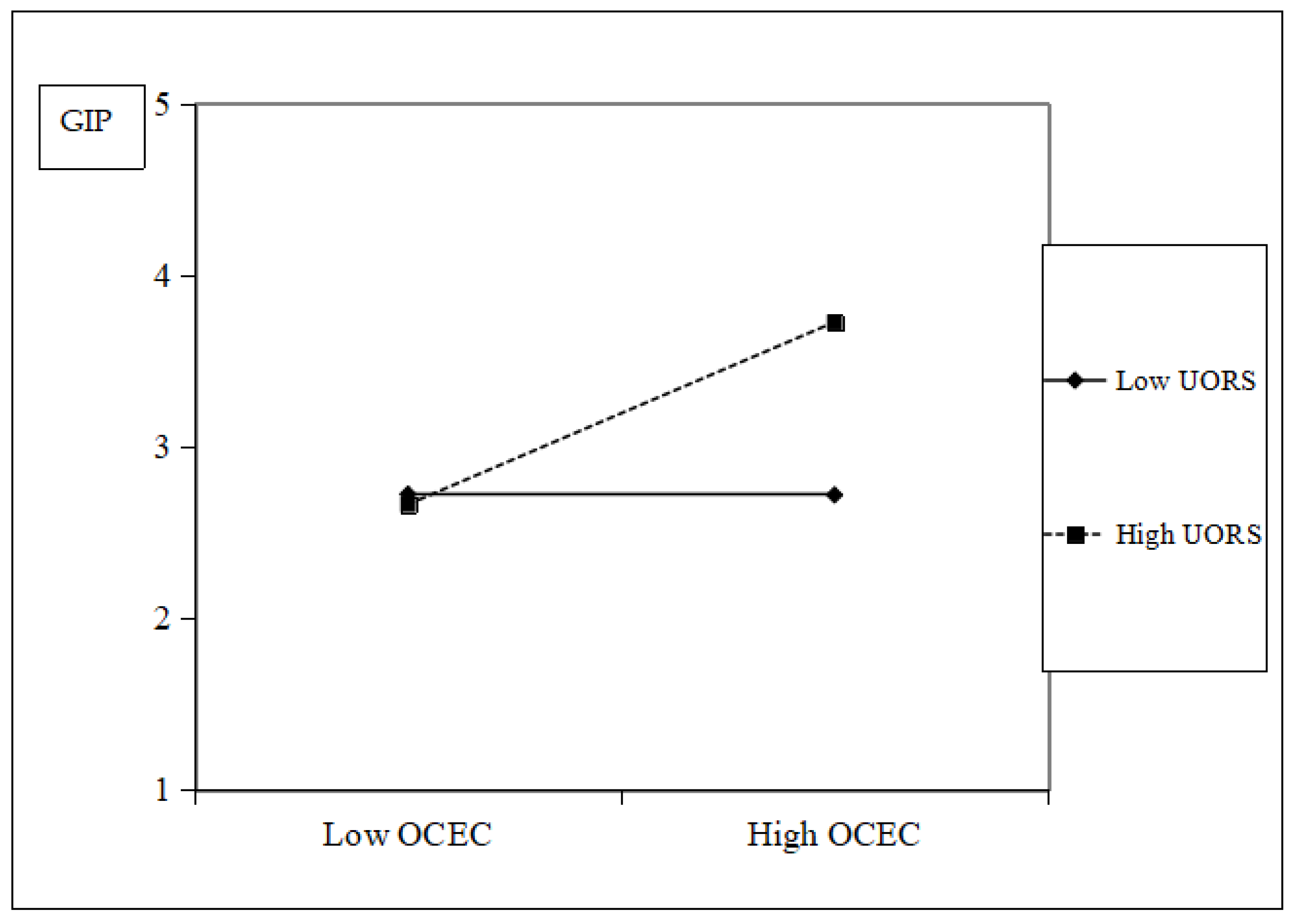

4.6. Test of Moderation Effect

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Research Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Akhtar, M. W., Garavan, T., Javed, M., Huo, C., Junaid, M., & Hussain, K. (2023). Responsible leadership, organizational ethical culture, strategic posture, and green innovation. The Service Industries Journal, 43(7–8), 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alalsheikh, S., Azim, M. T., & Uddin, M. A. (2022). Impact of social support on organizational citizenship behaviour: Does work–family conflict mediate the relationship? Global Business Review, 09721509221078932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albort-Morant, G., Leal-Millán, A., Cepeda-Carrion, G., & Henseler, J. (2018). Developing green innovation performance by fostering of organizational knowledge and coopetitive relations. Review of Managerial Science, 12(2), 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Koliby, I. S., Al-Swidi, A. K., Al-Hakimi, M. A., & Farhan, S. A. G. (2025). How green knowledge-oriented leadership drives green innovation in SMEs: The mediating role of environmental strategy and the moderating role of green AI capability. Cogent Business & Management, 12(1), 2520914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M., Moen, O., & Brett, P. O. (2020). The organizational climate for psychological safety: Associations with SMEs’ innovation capabilities and innovation performance. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 55, 101554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argiles-Bosch, J. M., Garcia-Blandon, J., & Martinez-Blasco, M. (2016). The impact of absorbed and unabsorbed slack on firm profitability: Implications for resource redeployment. In Resource redeployment and corporate strategy (pp. 371–395). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Arici, H. E., & Uysal, M. (2022). Leadership, green innovation, and green creativity: A systematic review. The Service Industries Journal, 42(5–6), 280–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M., & Baron, A. (2005). Managing performance: Performance management in action. CIPD publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bart, V., & Cullen, J. B. (1987). A theory and measure of ethical climate in organizations. In Research in corporate performance (pp. 57–71). JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, S., Ashfaq, M., Xia, E., & Awan, U. (2022). Does green transformational leadership lead to green innovation? The role of green thinking and creative process engagement. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(1), 580–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Justice in social exchange. Sociological Inquiry, 34(2), 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. H., & Chen, Y. S. (2013). Green organizational identity and green innovation. Management Decision, 51(5), 1056–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. S., Lai, S. B., & Wen, C. T. (2006). The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. Journal of Business Ethics, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., & Tang, Z. (2024). The effect of caring ethical climate on employees’ knowledge-hiding behavior: Evidence from Chinese construction firms. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedahanov, A. T., Rhee, C., & Yoon, J. (2017). Organizational structure and innovation performance: Is employee innovative behavior a missing link? Career Development International, 22(4), 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinc, M. S., & Huric, A. (2017). The impact of ethical climate types on nurses’ behaviors in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Nursing Ethics, 24(8), 922–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fornell, C. G., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. X., Hu, Z. P., Liu, C. S., Yu, D. J., & Yu, L. F. (2016). The relationships between regulatory and customer pressure, green organizational responses, and green innovation performance. Journal of Cleaner Production, 112, 3423–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jifri, A. O., Drnevich, P., & Tribble, L. (2016). The role of absorbed slack and potential slack in improving small business performance during economic uncertainty. Journal of Strategy and Management, 9(4), 474–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, T. K., Matthews, S. H., Matthews, M. J., & Henry, S. E. (2023). Humble leadership: A review and synthesis of leader expressed humility. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 44(2), 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S. R., Nixon, A. E., & Nord, W. R. (2017). Examining organic and mechanistic structures: Do we know as much as we thought? International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(4), 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskenvuori, J., Numminen, O., & Suhonen, R. (2019). Ethical climate in nursing environment: A scoping review. Nursing Ethics, 26(2), 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon Choi, B., Koo Moon, H., & Ko, W. (2013). An organization’s ethical climate, innovation, and performance: Effects of support for innovation and performance evaluation. Management Decision, 51(6), 1250–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. (2016). Does humble leadership behavior promote employees’voice behavior?—A dual mediating model. Open Journal of Business and Management, 4(4), 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlin, D., & Geiger, S. W. (2015). A reexamination of the organizational slack and innovation relationship. Journal of Business Research, 68(12), 2683–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Picazo, M. T., Galindo-Martin, M. A., & Perez-Pujol, R. S. (2024). Direct and indirect effects of digital transformation on sustainable development in pre- and post-pandemic periods. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 200, 123139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, D., Abell, J., & Sani, F. (2020). EBook: Social psychology 3e. McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, E. M., Walker, O. C., Jr., & Ruekert, R. W. (1995). Organizing for effective new product development: The moderating role of product innovativeness. Journal of Marketing, 59(1), 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, A. Y., Tsui, A. S., Kinicki, A. J., Waldman, D. A., Xiao, Z., & Song, L. J. (2014). Humble chief executive officers’ connections to top management team integration and middle managers’ responses. Administrative Science Quarterly, 59(1), 34–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, B. P., & Hekman, D. R. (2012). Modeling how to grow: An inductive examination of humble leader behaviors, contingencies, and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4), 787–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, B. P., Johnson, M. D., & Mitchell, T. R. (2013). Expressed humility in organizations: Implications for performance, teams, and leadership. Organization Science, 24, 1517–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasricha, P., Singh, B., & Verma, P. (2018). Ethical leadership, organic organizational cultures and corporate social responsibility: An empirical study in social enterprises. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 941–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J. L., & Delbecq, A. L. (1977). Organization structure, individual attitudes and innovation. Academy of Management Review, 2(1), 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polansky, S. H., & Hughes, D. W. (1986). Managerial innovation in newspaper organizations. Newspaper Research Journal, 8(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezan, M. (2011). Intellectual capital and organizational organic structure in knowledge society: How are these concepts related? International Journal of Information Management, 31(1), 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Torner, C. (2023). Ethical climate and creativity: The moderating role of work autonomy and the mediator role of intrinsic motivation. Cuadernos de Gestión, 23(2), 93–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Wang, G. Z., & Ma, X. (2020). Environmental innovation practices and green product innovation performance: A perspective from organizational climate. Sustainable Development, 28(1), 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanouli, A., & Hofmans, J. (2021). A resource-based perspective on organizational citizenship and counterproductive work behavior: The role of vitality and core self-evaluations. Applied Psychology, 70(4), 1435–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X., Xu, A., Lin, W., Chen, Y., Liu, S., & Xu, W. (2020). Environmental leadership, green innovation practices, environmental knowledge learning, and firm performance. Sage Open, 10(2), 2158244020922909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z., Li, J., Yang, Z., & Li, Y. (2011). Exploratory learning and exploitative learning in different organizational structures. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(4), 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D., Zeng, S., Lin, H., Yu, M., & Wang, L. (2021). Is green the virtue of humility? The influence of humble CEOs on corporate green innovation in China. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 70(12), 4222–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J., & Peng, M. W. (2003). Organizational slack and firm performance during economic transitions: Two studies from an emerging economy. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1249–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M. L., Tan, R. R., & Siriban-Manalang, A. B. (2013). Sustainable consumption and production for Asia: Sustainability through green design and practice. Journal of Cleaner Production, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanacker, T., Collewaert, V., & Zahra, S. A. (2017). Slack resources, firm performance, and the institutional context: Evidence from privately held European firms. Strategic Management Journal, 38, 1305–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | NFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model (HL, OCEC, GIP, OS, UORS) | 793.029 | 454 | 1.747 | 0.049 | 0.968 | 0.928 |

| One-factor model (HL + OCEC + GIP + OS + UORS) | 6845.166 | 464 | 14.753 | 0.212 | 0.394 | 0.379 |

| Convergent Validity | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | AVE | CR |

| HL | 0.748 | 0.964 |

| OCEC | 0.765 | 0.958 |

| GIP | 0.767 | 0.963 |

| OS | 0.755 | 0.939 |

| UORS | 0.798 | 0.922 |

| Mean | SD | Ownership | Scale | HL | OCEC | GIP | OS | UORS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ownership | 1.758 | 0.429 | 1 | ||||||

| Scale | 2.431 | 0.740 | 0.061 | 1 | |||||

| HL | 3.213 | 1.048 | 0.013 | −0.071 | (0.865) | ||||

| OCEC | 3.385 | 1.084 | 0.056 | −0.094 | 0.288 ** | (0.875) | |||

| GIP | 3.069 | 1.039 | 0.020 | −0.049 | 0.418 ** | 0.434 ** | (0.893) | ||

| OS | 3.364 | 1.060 | 0.100 | −0.060 | 0.308 ** | 0.329 ** | 0.438 ** | (0.876) | |

| UORS | 3.261 | 1.161 | 0.075 | −0.061 | 0.339 ** | 0.326 ** | 0.436 ** | 0.347 ** | (0.869) |

| GIP (Model 1) | OCEC (Model 2) | GIP (Model 3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 1.745 ** (5.248) | 2.469 ** (6.779) | 0.936 (2.805) |

| HL | 0.413 ** (7.951) | 0.292 ** (5.131) | 0.317 ** (6.267) |

| OCEC | 0.328 ** (6.673) | ||

| 306 | 306 | 306 | |

| R2 | 0.176 | 0.092 | 0.282 |

| Control variables: scale, ownership | |||

| Direct effect | effect | lower limit | upper limit |

| HL → GIP | 0.3172 | 0.2176 | 0.4168 |

| Indirect effect | effect | lower limit | upper limit |

| HL → OCEC → GIP | 0.0956 | 0.056 | 0.1438 |

| Control variables: scale, ownership | |||

| Dependent Variable: GIP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t | p | β | |

| constant | 2.956 ** | 12.777 | 0.000 | - |

| OS | 0.167 ** | 3.499 | 0.001 | 0.17 |

| UORS | 0.204 ** | 4.623 | 0.000 | 0.228 |

| OCEC | 0.244 ** | 5.525 | 0.000 | 0.255 |

| OCEC × UORS | 0.212 ** | 5.625 | 0.000 | 0.260 |

| OCEC × OS | 0.211 ** | 4.347 | 0.000 | 0.204 |

| Control variable: scale ownership | ||||

| n | 306 | |||

| R2 | 0.470 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tu, T.; Choi, M. The Impact of Humble Leadership on the Green Innovation Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091170

Tu T, Choi M. The Impact of Humble Leadership on the Green Innovation Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091170

Chicago/Turabian StyleTu, Tianye, and MyeongCheol Choi. 2025. "The Impact of Humble Leadership on the Green Innovation Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises: A Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091170

APA StyleTu, T., & Choi, M. (2025). The Impact of Humble Leadership on the Green Innovation Performance of Chinese Manufacturing Enterprises: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091170