Embodied Impact of Facial Coverings: Triggering Self-Expression Needs to Drive Conspicuous Preferences

Abstract

1. Introduction

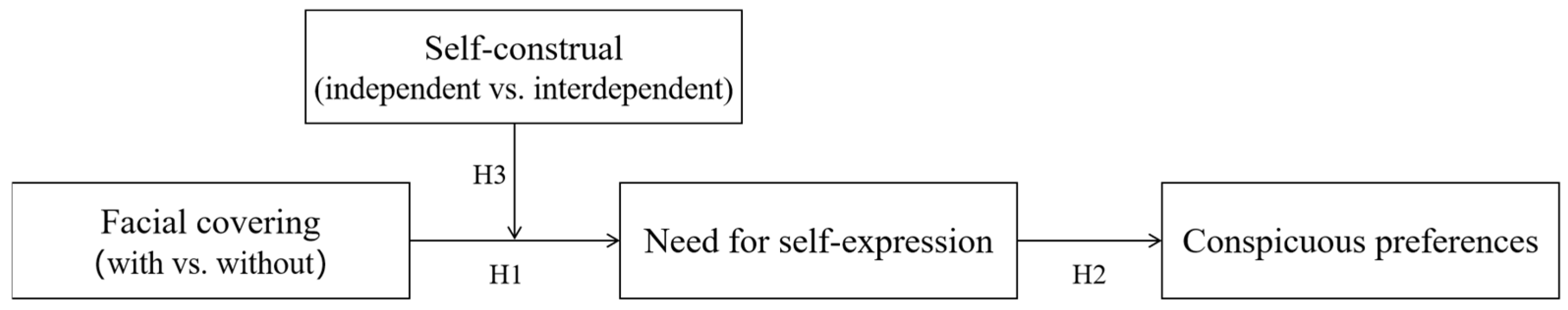

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Facial Covering and the Need for Self-Expression

2.2. Facial Covering: From Self-Expression Gap to Conspicuous Preferences

2.3. Moderating Role of Self-Construal

3. Methodology

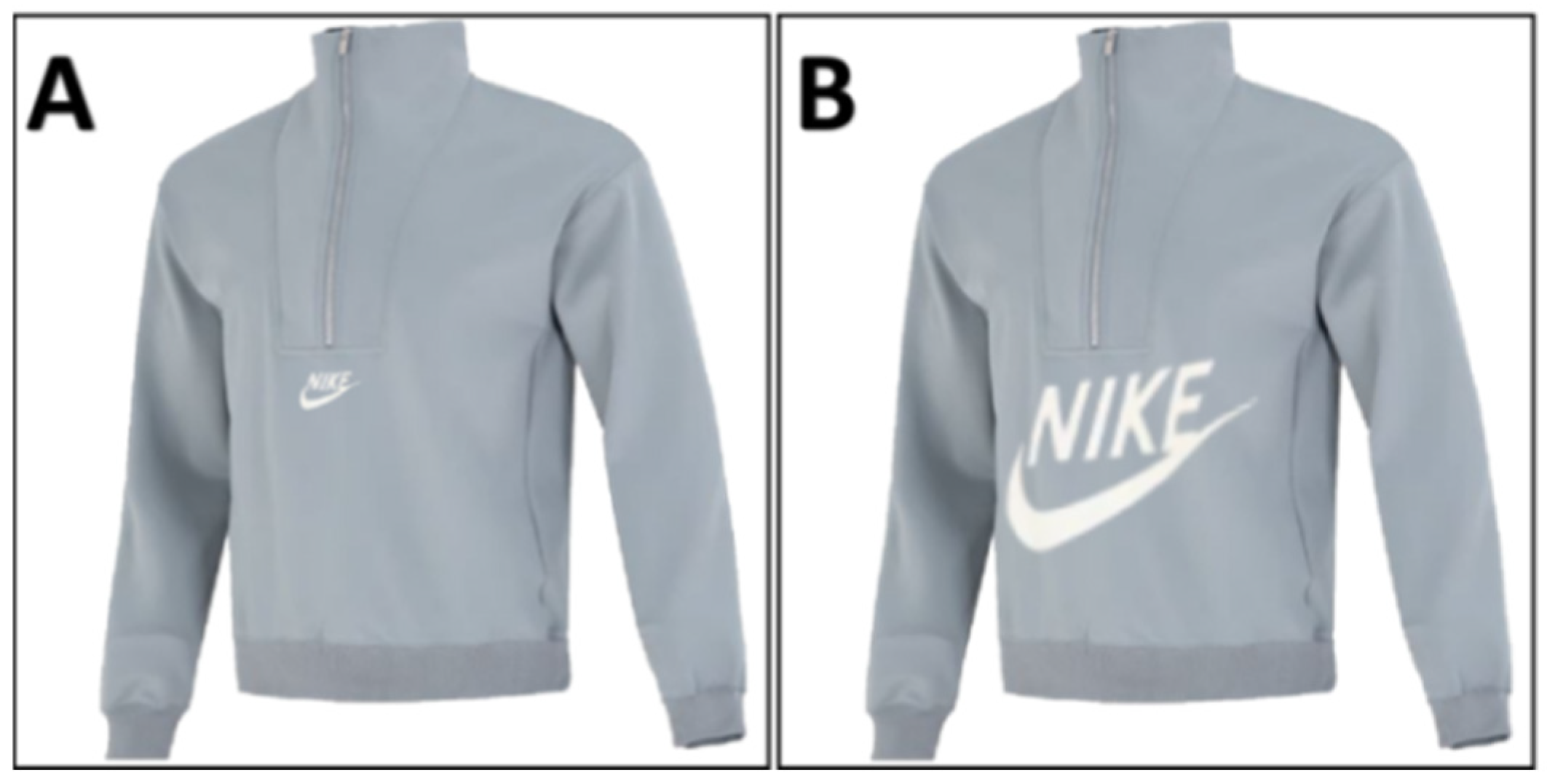

3.1. Hypothesis Validation

3.2. Facial Covering Stimulus Selection

3.3. Sample Acquisition and Ethical Safeguards

4. Study 1: Examining the Impact of Facial Covering on the Need for Self-Expression

4.1. Experiment 1

4.1.1. Participants and Procedure

4.1.2. Results

4.2. Experiment 2

4.2.1. Participants and Procedure

4.2.2. Results

4.3. Discussion

5. Study 2: Exploring the Influence of Facial Covering on Conspicuous Preferences and the Mediating Role of the Need for Self-Expression

5.1. Experiment 3

5.1.1. Participants and Procedure

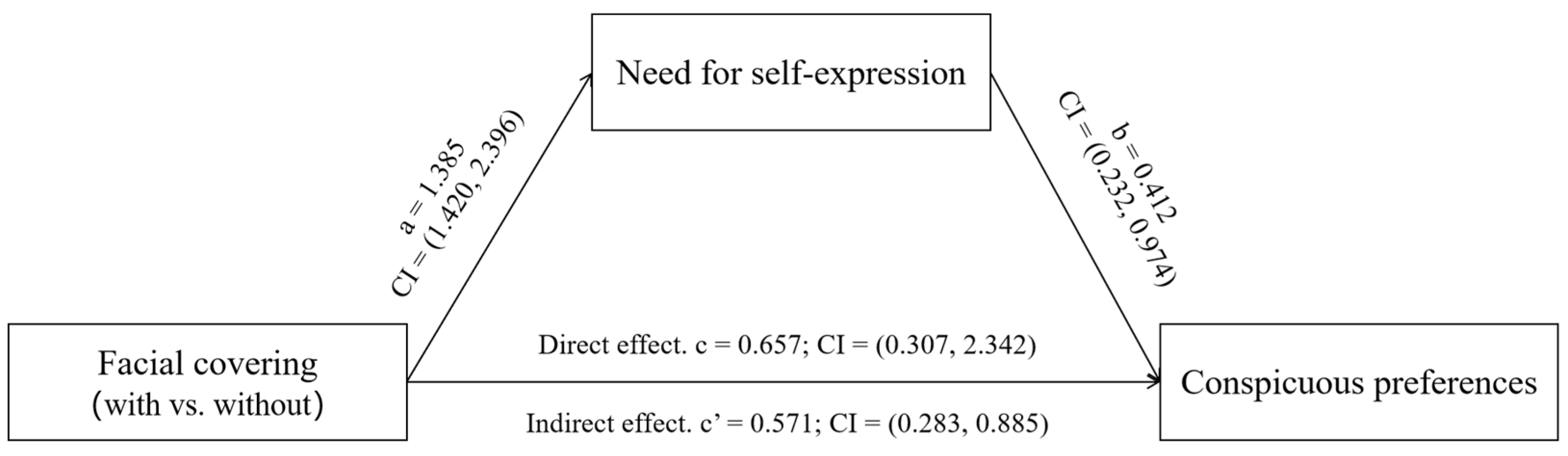

5.1.2. Results

5.2. Experiment 4

5.2.1. Participants and Procedure

5.2.2. Results

5.3. Discussion

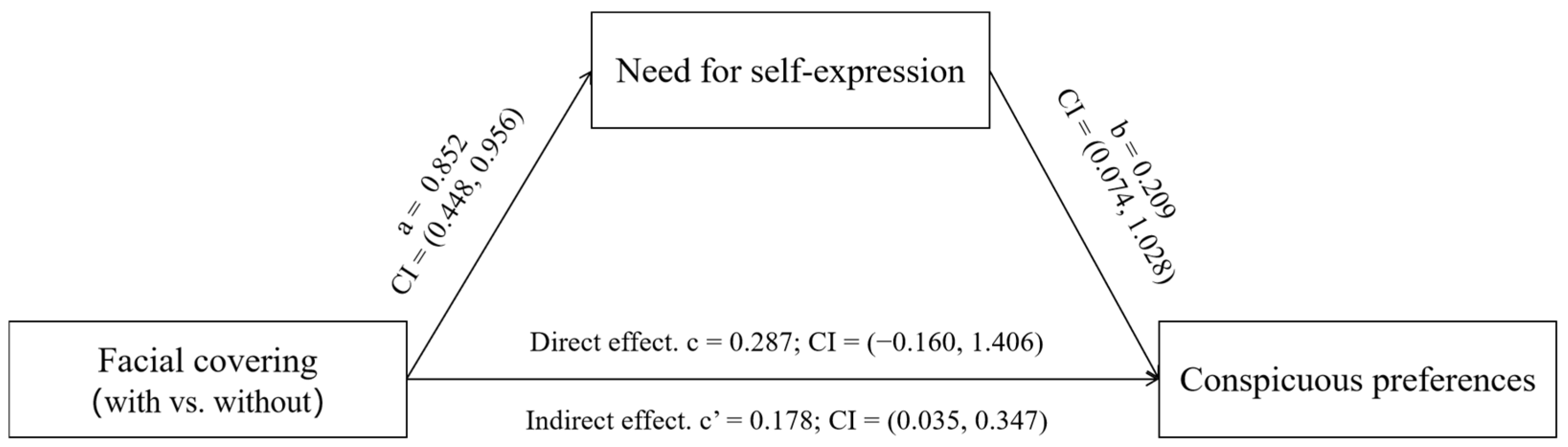

6. Study 3: Testing the Moderating Role of Self-Construal

6.1. Procedures and Measures

6.2. Results

6.3. Discussion

7. Discussion and Conclusions

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Practical Implications

7.3. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amadeo, M. B., Escelsior, A., Amore, M., Serafini, G., Pereira da Silva, B., & Gori, M. (2022). Face masks affect perception of happy faces in deaf people. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 12424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balabanis, G., & Karpova, A. (2025). The personality of luxury. A new measure and the effects of brand personality distinctiveness and congruence on consumer responses. Journal of Business Research, 189, 115107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M. L., Valmaggia, L. R., Fergusson, L. G. H., & Morris, R. G. (2025). The impact of covering the lower face on facial emotion recognition: A systematic review. Psychology & Neuroscience, 18(2), 77–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennetts, R. J., Johnson, H. P., Zielinska, P., & Bate, S. (2022). Face masks versus sunglasses: Limited effects of time and individual differences in the ability to judge facial identity and social traits. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self-representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(1), 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, A. J., Young, A. W., Keane, J., & Dean, M. (2000). Configural information in facial expression perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 26(2), 527–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W., Chen, H., Gao, X., & Jackson, T. (2009). Choice, self-expression, and the diffusion effect of choice. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 41(8), 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon, C. C. (2020). Wearing face masks strongly confuses counterparts in reading emotions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 566886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castelli, L., Tumino, M., & Carraro, L. (2022). Face mask use as a categorical dimension in social perception. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 17860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, H., & Akdemir Cengiz, H. (2023). Tourists’ need for uniqueness and ethnic food purchase intention: A moderated serial mediation model. Appetite, 190, 107004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, E. Y., & Septianto, F. (2024). Self-construals and health communications: The persuasive roles of guilt and shame. Journal of Business Research, 170, 114357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, K. K., Hurst, E., & Roussanov, N. (2009). Conspicuous consumption and race. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(2), 425–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheek, N. N., Schwartz, B., & Shafir, E. (2023). Choice set size shapes self-expression. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(2), 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E. Y. I., Yeh, N. C., & Wang, C. P. (2008). Conspicuous consumption: A preliminary report of scale development and validation. Advances in Consumer Research, 35, 686–687. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, R. W., & Lam, S. F. (2007). Self-construal and social comparison effects. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(1), 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chovanec, J. (2021). Saving one’s face from unintended humour: Impression management in follow-up sports interviews. Journal of Pragmatics, 176, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S. E., Bacon, P. L., & Morris, M. L. (2000). The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 791–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z., Liu, Y., Sun, X., Shang, Z., & Xu, M. (2024). Veiled to express: Uncovering the effect of mask-wearing on voice behavior in the workplace. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAndrea, D. C., Shaw, A. S., & Levine, T. R. (2010). Online language: The role of culture in self-expression and self-construal on facebook. Journal of Language & Social Psychology, 29(4), 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vignemont, F. (2011). Embodiment, ownership and disownership. Consciousness & Cognition, 20(1), 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., & Yang, C. (2021). How social crowding affects conspicuous consumption: The mediating role of the need for self-expression. Nankai Business Review, 24(4), 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, R., Kirmani, A., & Matherly, T. (2013). Look at me! Look at me! Conspicuous brand usage, self-brand connection, and dilution. Journal of Marketing Research, 50(4), 477–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foglia, L., & Wilson, R. A. (2013). Embodied cognition. WIREs: Cognitive Science, 4(3), 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freud, E., Stajduhar, A., Rosenbaum, R. S., Avidan, G., & Ganel, T. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic masks the way people perceive faces. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 22344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M., & Cui, B. (2016). Literature review on product distinctiveness evaluation and consumer choice based on need for uniqueness. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 6, 840–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbertson, K., & Ewert, A. (2015). Stability of motivations and risk attractiveness: The adventure recreation experience. Risk Management, 17, 276–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K., Hare, A., & Liu, C. H. (2022). Impact of face masks and viewers’ anxiety on ratings of first impressions from faces. Perception, 51, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q. Q., Deng, X., & Guo, W. D. (2020). The impact of social crowding on willingness to donate money: The mediating role of self-expression needs. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(5), 1211–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y. J., Nunes, J. C., & Drèze, X. (2010). Signaling status with luxury goods: The role of brand prominence. Journal of Marketing, 74(4), 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, E., Graupmann, V., Niesta, K. D., Zanna, M., Traut-Mattausch, E., & Frey, D. (2009). Culture, self, and the emergence of reactance: Is there a “universal” freedom? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(5), 1068–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardes, F., Fischer, E., Spiller, S., Labroo, A., Bublitz, M., Peracchio, L., & Huber, J. (2022). Commentaries on “An intervention-based abductive approach to generating testable theory”. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 32(1), 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2000). Of wealth and death: Materialism, mortality salience, and consumption behavior. Psychological Science, 11(4), 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellaris, J. J., Machleit, K., & Gaffney, D. R. (2020). Sign evaluation and compliance under mortality salience: Lessons from a pandemic. Interdisciplinary Journal of Signage and Wayfinding, 4(2), 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. S., & Drolet, A. (2003). Choice and self-expression: A cultural analysis of variety-seeking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H. S., & Sherman, D. K. (2007). “Express yourself”: Culture and the effect of self-expression on choice. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 92(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., & Rucker, D. D. (2012). Bracing for the psychological storm: Proactive versus reactive compensatory consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(4), 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimiecik, J., & Teas, E. (2025). Express your self: Exploring the nature of the expressive self and the health and well-being consequences of its restriction in a market society. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 65(1), 157–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krys, K., Vignoles, V. L., de Almeida, I., & Uchida, Y. (2022). Outside the “cultural binary”: Understanding why Latin American collectivist societies foster independent selves. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(4), 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Shrum, L. J. (2012). Conspicuous consumption versus charitable behavior in response to social exclusion: A differential needs explanation. Journal of Consumer Research, 39(3), 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., & Jeong, S. K. (2023). When less is not more: The effect of transparent masks on facial attractiveness judgment. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 8(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Chi, X., Li, J., Zhou, S., & Cheng, Y. (2025). Doctors’ self-presentation strategies and the effects on patient selection in psychiatric department from an online medical platform: A combined perspective of impression management and information integration. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. M. C., Jiménez, B. J., Bilro, R. G., & Romero, J. (2024). Me and my AI: Exploring the effects of consumer self-construal and AI-based experience on avoiding similarity and willingness to pay. Psychology & Marketing, 41(1), 151–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. G., Song, L. L., Zheng, Y., & Wang, L. C. (2022). Masks as a moral symbol: Masks reduce wearers’ deviant behavior in China during COVID-19. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(41), e2211144119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R. (1984). Conspicuous consumption: A literature review. European Journal of Marketing, 18(3), 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, G. (2023). A cross-cultural study of mask-wearing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparing China, Japan and the USA. Etnoantropoloski Problemi-Issues in Ethnology and Anthropology, 18(1), 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, D., & Willingham, B. (2006). The thrill of victory and the agony of defeat: Spontaneous expressions of medal winners of the Athens Olympics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(3), 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, B., & Xing, N. (2024). Toy tourism: Exploring the co-creating roles of toy-tourist-destination congruence and self-construal in creating well-being and its outcomes. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, C., & Townsend, C. (2022). Why the drive: The utilitarian and hedonic benefits of self-expression through consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46(Suppl. C), 101320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Cass, A., & McEwen, H. (2004). Exploring consumer status and conspicuous consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 4(1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, M., & Garcia-Marques, T. (2022). The effect of facial occlusion on facial impressions of trustworthiness and dominance. Memory and Cognition, 50(6), 1131–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, R., Filoromo, S. J., Landgraf, L. A., Lynn, C. D., & Smetana, M. R. A. (2023). Deviance as an historical artefact: A scoping review of psychological studies of body modification. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 10(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L., & Lv, W. (2013). Application and revision of the self-construction scale in adults. China Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 710–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifkin, J. R., Du, K. M., & Berger, J. (2021). Penny for your preferences: Leveraging self-expression to encourage small prosocial gifts. Journal of Marketing, 85(3), 204–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D. D., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Conspicuous consumption versus utilitarian ideals: How different levels of power shape consumer behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P., Singh, J., & Wang, W. (2022). The influence of creative packaging design on customer motivation to process and purchase decisions. Journal of Business Research, 147, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singelis, T. M. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construal. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 580–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittenthaler, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., & Jonas, E. (2015). Observing the restriction of another person: Vicarious reactance and the role of self-construal and culture. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X., Huang, F., & Li, X. (2017). The effect of embarrassment on preferences for brand conspicuousness: The roles of self-esteem and self-brand connection. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 27(1), 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugitani, Y. (2018). The effect of self- and public-based evaluations on brand purchasing: The interplay of independent and interdependent self-construal. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 30(4), 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C. A. M., & Young, A. W. (2022). Understanding trait impressions from faces. British Journal of Psychology, 113(4), 1056–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takehara, T., Kaigawa, M., Kobayashi, A., & Yamaguchi, Y. (2023). Impact of face masks and sunglasses on attractiveness, trustworthiness, and familiarity, and limited time effect: A Japanese sample. Discover Psychology, 3(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, J. B., & Lew, Z. (2022). Self-transformation online through alternative presentations of self: A review, critique, and call for research. Annals of the International Communication Association, 46(3), 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Zhao, M., Gao, H. X., & Zhao, Y. (2023). Exploration of dimensions and scale development of compensatory consumption behavior. Chinese Journal of Management, 20(12), 1837–1846. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. J., & Griskevicius, V. (2014). Conspicuous consumption, relationships, and rivals: Women’s luxury products as signals to other women. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(5), 834–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., & Zhang, J. (2023). The value of information disclosure: Evidence from mask consumption in China. Journal of Environmental Economics & Management, 122, 102865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L., English, A. S., Talhelm, T., Li, X., Zhang, X., & Wang, S. (2025). People in tight cultures and tight situations wear masks more: Evidence from three large-scale studies in China. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 51(7), 1121–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2023). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Masks. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-masks (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Wright, C. D. (2008). Embodied cognition: Grounded until further notice. British Journal of Psychology, 99(1), 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E. C., Moore, S. G., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2019). Wine for the table: Self-construal, group size, and choice for self and others. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(3), 508–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. H., & Wang, L. C. (2023). Self-construction, conflict resolution style, and preference for polarized word-of-mouth products. Foreign Economics & Management, 45(6), 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J. Z., She, Z., Ju, K., Zhao, J. J., Hou, X. L., Peng, Y. N., Li, Y., & Zuo, Z. H. (2020). Development and validation of a risk perception scale for the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Capital Normal University (Social Sciences Edition), 4(1), 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D., Shen, H., & Wyer, R. S. (2021). The face is the index of the mind: Understanding the association between self-construal and facial expressions. European Journal of Marketing, 55(6), 1664–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S. Q., Chen, J., Lv, W., & Pan, L. (2016). Independent self “frugal for others,” interdependent self “frugal for self”: The impact of self-construction on savings and consumption choices for self vs. others. Management Review, 28(6), 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., Liu, Q., March, D. S., Hicks, L. L., & McNulty, J. K. (2024). Leveraging impression management motives to increase the use of face masks. The Journal of Social Psychology, 164(6), 930–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q., Chen, X., & Zeng, H. (2025). Buying conspicuous organic food when it’s crowded: How social crowding and the need for self-expression influence organic food choices. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 9, 1486469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X. Y., & Peng, S. Q. (2014). Compensatory consumption behavior: Concept, types, and psychological mechanisms. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(9), 1513–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C. B., Bohns, V. K., & Gino, F. (2010). Good lamps are the best police: Darkness increases dishonesty and self-interested behavior. Psychological Science, 21(3), 311–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y., Ren, Y., He, L., & Li, J. (2024). Research on the implicit demand factors of mask purchase in the post-pandemic background: Evidence from China. Academic Journal of Business & Management, 6(9), 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D., Jin, L., He, Y., & Xu, Q. (2014). The effect of the sense of power on Chinese consumers’ uniqueness-seeking behavior. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 26(1), 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, J.; Liang, X. Embodied Impact of Facial Coverings: Triggering Self-Expression Needs to Drive Conspicuous Preferences. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091150

Li J, Liang X. Embodied Impact of Facial Coverings: Triggering Self-Expression Needs to Drive Conspicuous Preferences. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091150

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Ji, and Xv Liang. 2025. "Embodied Impact of Facial Coverings: Triggering Self-Expression Needs to Drive Conspicuous Preferences" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091150

APA StyleLi, J., & Liang, X. (2025). Embodied Impact of Facial Coverings: Triggering Self-Expression Needs to Drive Conspicuous Preferences. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1150. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091150