Neighborhood Conditions in a New Destination Context and Latine Youth’s Ethnic–Racial Identity: What’s Gender Got to Do with It?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Theoretical Frameworks

1.2. Ethnic Racial Identity and Socialization in Context

1.3. Gender Role Beliefs and Cultural Scripts

1.4. Individual-Level Influences on GRS Beliefs and ERI

1.5. Neighborhood-Level Influences on GRS Beliefs and ERI

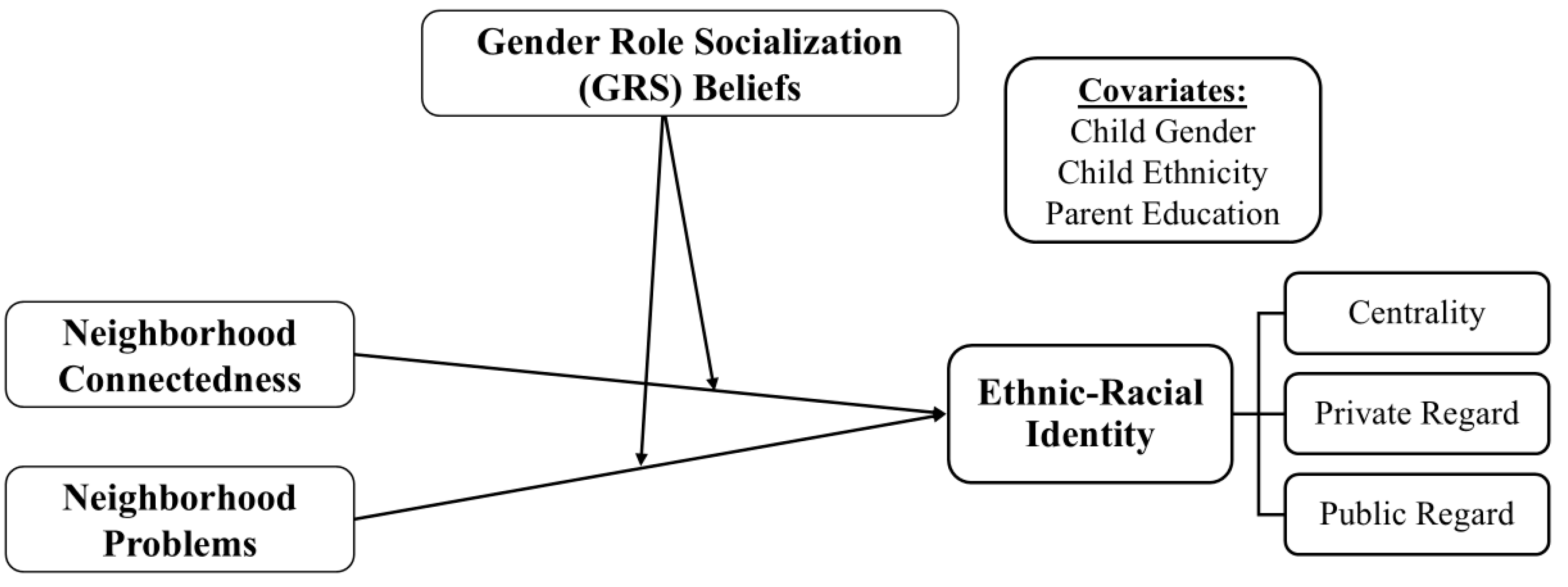

1.6. Study Aims and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Residential Neighborhood Measures

2.2.2. Socialization Measures

2.2.3. Adolescents’ Ethnic–Racial Identity (ERI)

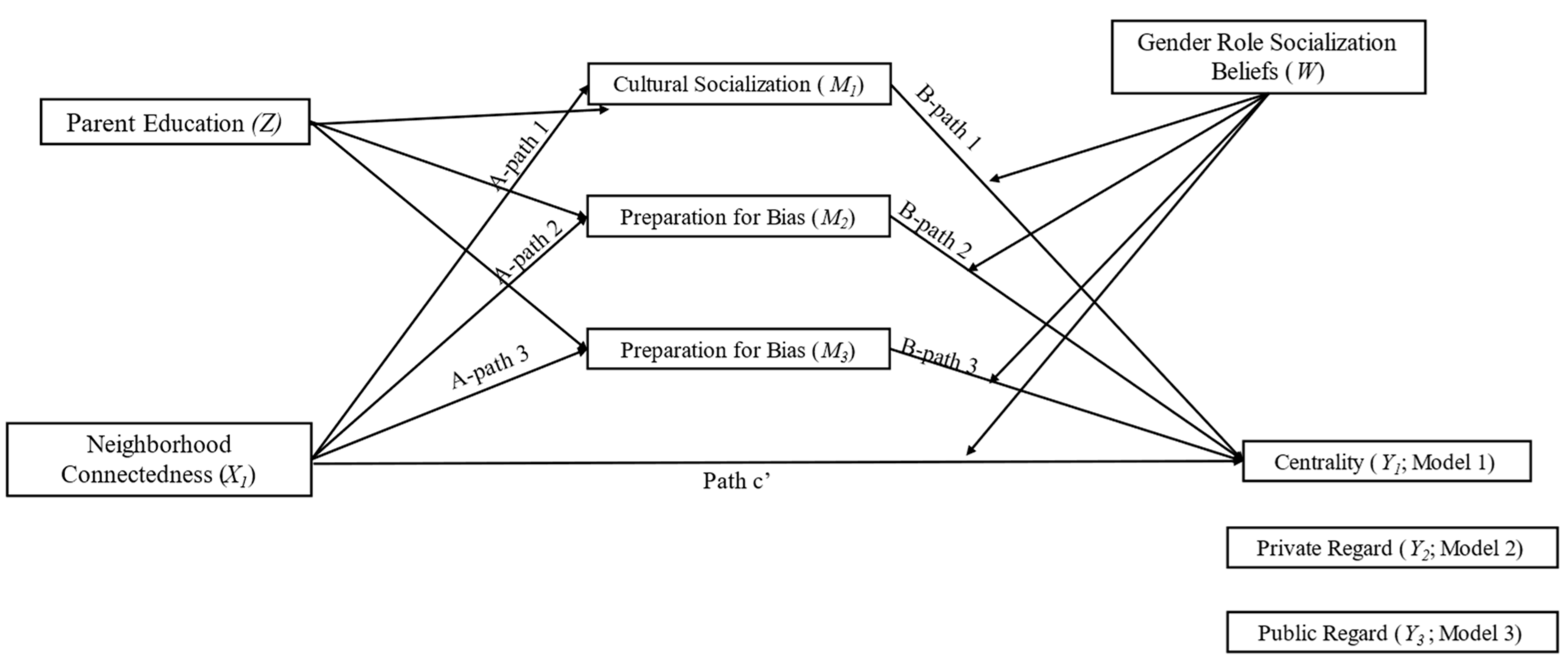

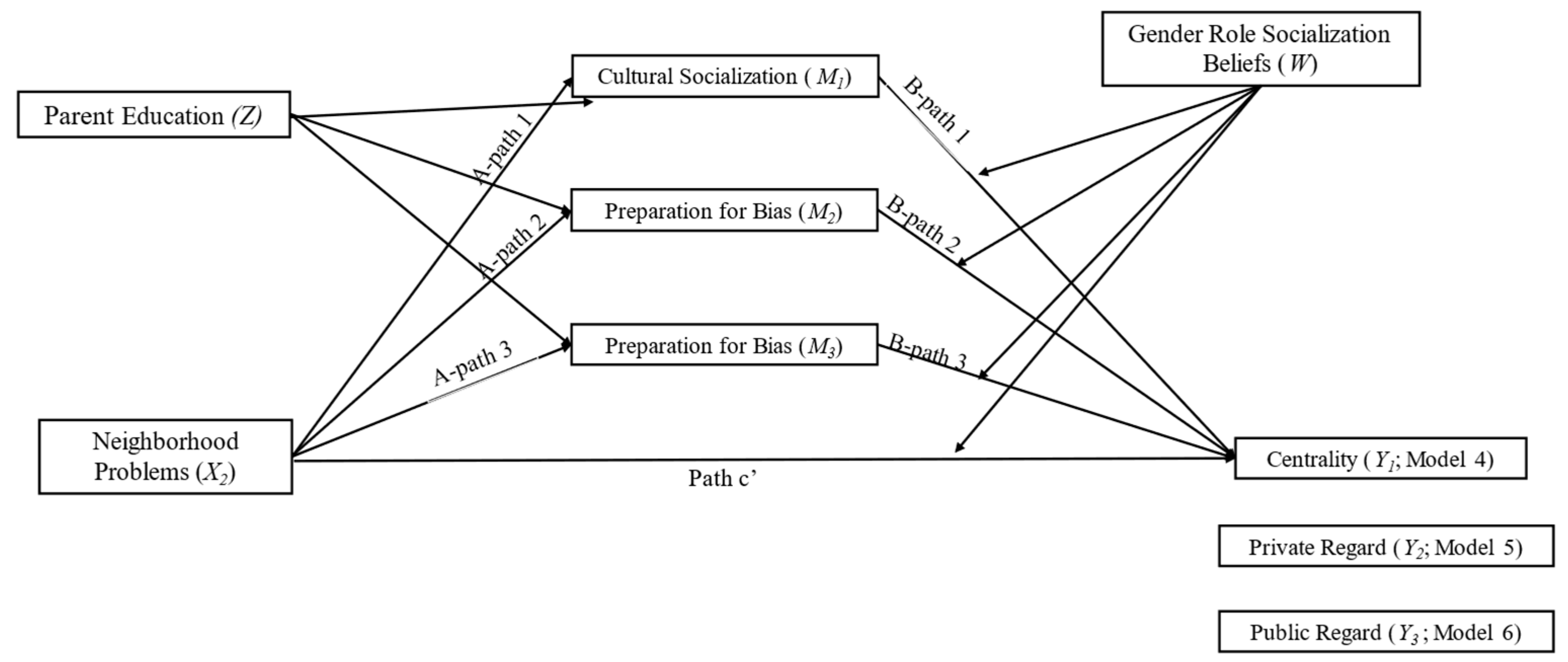

2.3. Analytic Plan

2.4. Preliminary Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Neighborhood Connectedness, GRS Beliefs, and ERI Outcomes

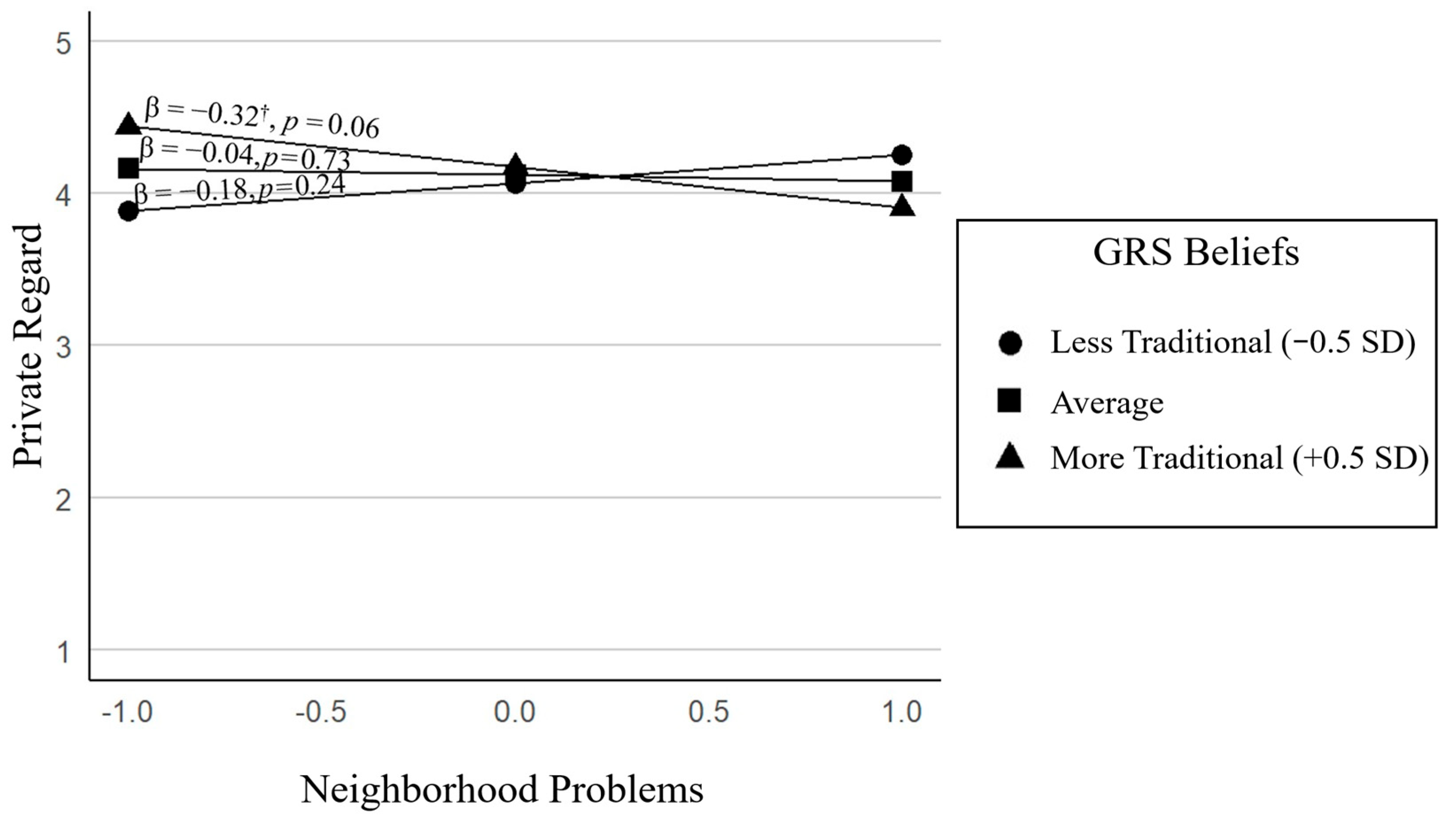

3.2. Neighborhood Problems, GRS, and ERI Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Neighborhood Effects on ERI

4.2. GRS Beliefs as a Moderator

4.3. GRS Beliefs Vs. ERS Practices and Null Effects

4.4. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Parent-Reported ERS Measures and Exploratory Moderated Mediation Analysis Details

| Neighborhood Connectedness Models (1–3) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consequent | ||||||||||

| (a-path is the same for models 1–3) | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

| M1 (CS) | M2 (PB) | M3 (PMT) | Y1 (Centrality) | Y2 (Private Regard) | Y3 (Public Regard) | |||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | ||||

| Constant | i1 | −0.57 * (0.25) | −0.27 (0.29) | 0.17 (0.27) | 0.33 (0.58) | 40.31 (0.39) *** | 0.46 (0.55) | |||

| X (RN Connectedness) | a1 | 0.05 (0.12) | 0.03 (0.12) | 0.18 (0.13) | c’ | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.21 (0.11) | 0.06 (0.13) | ||

| Z (Parent Education) | a2 | 0.28 ** (0.10) | 0.14 (0.12) | 0.19 (0.11) | −0.16 (0.21) | −0.07 (0.14) | −0.22 (0.19) | |||

| R2 = 0.10 | R2 = 0.03 | R2 = 0.02 | ||||||||

| F(2, 57) = 3.79 * | F(2, 57) = 0.66 | F(2, 57) = 0.55 | ||||||||

| M (ERS) | ||||||||||

| M1 (CS) | – | – | – | – | – | b1 | 0.28 (0.31) | 0.01 (0.20) | 0.16 (0.30) | |

| M2 (PB) | – | – | – | – | – | b2 | −0.26 (0.23) | −0.19 (0.15) | −0.21 (0.20) | |

| M3 (PMT) | – | – | – | – | – | b3 | 0.05 (0.24) | 0.21 (0.13) | 0.18 (0.20) | |

| W (GRS Beliefs) | – | – | – | – | – | b4 | 0.25 (0.41) | −0.06 (0.27) | −0.11 (0.36) | |

| X × W | – | – | – | – | – | b5 | 0.23 (0.69) | 0.09 (0.43) | 0.30 (0.68) | |

| M1 × W | – | – | – | – | – | b6 | −0.40 (0.34) | −0.03 (0.24) | 0.05 (0.39) | |

| M2 × W | – | – | – | – | – | b7 | 0.54 (0.28) † | 0.37 (0.21) | 0.22 (0.33) | |

| M3 × W | – | – | – | – | – | b8 | −0.47 (10.65) | −0.45 (10.01) | −0.39 (10.71) | |

| R2 = 0.24 | R2 = 0.24 | R2 = 0.24 | ||||||||

| F(10, 49) = 2.17 ** | F(10, 49) = 2.17 * | F(10, 49) = 2.23 * | ||||||||

| Moderated mediation | Index, 95% CI | Index, 95% CI | Index, 95% CI | |||||||

| M1 (CS) | −0.02 [−0.18, 0.09] | 0.00 [−0.10, 0.07] | −0.00 [−0.07, 0.07] | |||||||

| M2 (PB) | 0.02 [−0.12, 0.22] | 0.01 [−0.08, 0.11] | 0.01 [−0.08, 0.14] | |||||||

| M3 (PMT) | −0.05 [−0.24, 0.08] | −0.04 [−0.21, 0.05] | −0.04 [−0.20, 0.07] | |||||||

| Neighborhood Problems Models (4–6) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consequent | |||||||

| (a-path is the same for models 4–6) | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | ||||

| M1 (CS) | M2 (PB) | M3 (PMT) | Y1 (Centrality) | Y2 (Private Regard) | Y3 (Public Regard) | ||

| Antecedent | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | Coeff. (SE) | |

| Constant | −0.56 (0.25) * | −0.27 (0.27) | 0.18 (0.27) | 0.28 (0.31) | 0.11 (0.24) | 0.42 (0.22) | |

| X (RN Problems) | 0.00 (0.17) | 0.28 (0.15) | 0.18 (0.20) | c’ | −0.25 (0.23) | −0.03 (0.14) | −0.07 (0.15) |

| Z (Parent Education) | 0.28 (0.10) ** | 0.14 (0.11) | −0.09 (0.11) | −0.15 (0.12) | −0.06 (0.09) | −0.21 (0.09) * | |

| R2 = 0.10 | R2 = 0.09 | R2 = 0.04 | |||||

| F(2, 57) = 3.65 * | F(2, 57) = 2.51 | F(2, 57) = 0.76 | |||||

| M (ERS) | |||||||

| M1 (CS) | – | – | – | b1 | 0.29 (0.19) | 0.04 (0.14) | 0.19 (0.17) |

| M2 (PB) | – | – | – | b2 | −0.25 (0.19) | −0.22 (0.13) | −0.23 (0.16) |

| M3 (PMT) | – | – | – | b3 | 0.12 (0.21) | 0.25 (0.13) † | 0.25 (0.16) |

| W (GRS Beliefs) | – | – | – | b4 | 0.26 (0.24) | −0.01 (0.16) | −0.05 (0.17) |

| X × W | – | – | – | b5 | −0.61 (0.38) | −0.56 (0.24) * | −0.57 (0.27) * |

| M1 × W | – | – | – | b6 | −0.35 (0.33) | −0.14 (0.23) | 0.04 (0.36) |

| M2 × W | – | – | – | b7 | 0.58 (0.29) † | 0.40 (0.21) † | 0.27 (0.34) |

| M3 × W | – | – | – | b8 | −0.12 (0.38) | −0.09 (0.31) | −0.07 (0.25) |

| R2 = 0.30 | R2 = 0.26 | R2 = 0.28 | |||||

| F(10, 49) = 3.12 ** | F(10, 49) = 1.61 | F(10, 49) = 1.82 | |||||

| Moderated mediation | Index, 95% CI | Index, 95% CI | Index, 95% CI | ||||

| M1 (CS) | 0.00 [−0.17, 0.19] | 0.00 [−10, 0.10] | 0.00 [−0.10, 0.11] | ||||

| M2 (PB) | 0.16 [−0.03, 0.54] | 0.11 [−0.03, 0.34] | 0.08 [−0.02, 0.37] | ||||

| M3 (PMT) | −0.02 [−0.29, 0.15] | −0.02 [−0.21, 0.12] | −0.01 [−0.19, 0.09] | ||||

| 1 | The gender-neutral term Latine is used in the current study for two reasons. First, the current study sample did not require adolescents or parents to identify as binary gender identities (i.e., Latino/a). Second, the term Latine aligns better with the grammatical structure of the Spanish language and has been increasingly used by Spanish speakers and younger generations as a more accessible alternative to Latinx (Miranda et al., 2023). |

| 2 | To ensure that the exclusion of reverse-coded items did not artificially inflate reliability or change our interpretation of results, we reran analyses (i.e., Models 1–6) using the full original subscales, including reverse-coded items. The overall patterns of results remained consistent, including the key interaction term between neighborhood problems and GRS. Full results from these robustness checks are available upon request. |

| 3 | The same participants missing data for the private regard subscale also were missing data for the public regard subscale and again replaced with the sample subscale mean (i.e., M = 3.28, SD = 0.72). |

| 4 | We do not conceptualize neighborhood problems (or connectedness) as proxies for American culture. Instead, neighborhood context is a proximal development setting that may intersect with, but remains distinct from, broader societal ideologies and family-held cultural beliefs [Witherspoon et al., 2023]. These exploratory pilot findings reflect the interaction of multiple, layered influences on adolescent development in new destination contexts. |

| 5 | For a comprehensive history of how gender and sex have been conceptually, empirically, and ontologically conflated—especially in relation to race—in child development fields, see How the Clinic Made Gender (Eder, 2022). |

References

- Aber, M. S., & Nieto, M. (2000). Suggestions for the investigation of psychological wellness in the neighborhood context: Toward a pluralistic neighborhood theory. In The promotion of wellness in children and adolescents (pp. 185–219). CWLA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, M., Coltrane, S., & Parke, R. D. (2007). Cross-ethnic applicability of the gender-based attitudes toward marriage and child rearing scales. Sex Roles, 56(5–6), 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychology Association. (2023). Gender Role. In APA dictionary of psychology. APA Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo Dawson, B., & Quiros, L. (2014). The effects of racial socialization on the racial and ethnic identity development of Latinas. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(4), 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciniega, G. M., Anderson, T. C., Tovar-Blank, Z., & Tracey, T. J. G. (2008). Toward a fuller conception of machismo: Development of a traditional machismo and Caballerismo scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55(1), 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardelt, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2001). Effects of mothers’ parental efficacy beliefs and promotive parenting strategies on inner-city youth. Journal of Family Issues, 22(8), 944–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayón, C., Nieri, T., & Ruano, E. (2020). Ethnic-racial socialization among Latinx families: A systematic review of the literature. Social Service Review, 94(4), 693–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyak, M. A. (2004). What you see may not be what you get: A brief, nontechnical introduction to overfitting in regression-type models. Biopsychosocial Science and Medicine, 66(3), 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- Benner, A. D., & Kim, S. Y. (2010). Understanding Chinese American adolescents’ developmental outcomes: Insights from the family stress model. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez, D. L., Garcia, M. E., Iturriaga, V. F., Rodriguez, R. E., & Gonzales-Backen, M. (2025). Latinx Youth in Rural Settings: Understanding the Links Between Ethnic-Racial Identity, Neighborhood Risks, Perceived Discrimination, and Depressive Symptoms. Journal of adolescence, 97(4), 1103–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M. H. (2013). Cultural approaches to parenting. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brisson, D., Lechuga Peña, S., Mattocks, N., Plassmeyer, M., & McCune, S. (2019). Effects of your family, your neighborhood intervention on neighborhood social processes. Social Work Research, 43(4), 235–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookings Institution. (2025, April 30). 100 days of immigration under the second Trump administration. Brookings. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/100-days-of-immigration-under-the-second-trump-administration/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Cahill, K. M., Updegraff, K. A., Causadias, J. M., & Korous, K. M. (2021). Familism values and adjustment among Hispanic/Latino individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(9), 947–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capielo Rosario, C., Mattwig, T., Hamilton, K. D., & Wejrowski, B. (2023). Conceptualizing puerto rican migration to the United States. Current Opinion in Psychology, 51, 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, L. G., Perez, F. V., Castillo, R., & Ghosheh, M. R. (2010). Construction and initial validation of the marianismo beliefs scale. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 23(2), 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, C. G., Lamberty, G., Jenkins, R., McAdoo, H. P., Crnic, K., Wasik, B. H., & García, H. V. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, F. (2022). Documentation status socialization as an ethnic-racial socialization dimension: Incorporating the experience of mixed-status Latinx families. Studies in Social Justice, 16(1), 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGue, S., Singleton, R., & Kearns, M. (2024). A qualitative analysis of beliefs about masculinity and gender socialization among U.S. mothers and fathers of school-age boys. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 25(2), 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeJonckheere, M., Fisher, A., & Chang, T. (2018). How has the presidential election affected young Americans? Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, S. (2022). How the clinic made gender: The medical history of a transformative idea. In How the clinic made gender. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest, N., & Morse, E. (2015). Ethnic variations in parental ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity: A longitudinal study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, S. E., & Chavez, N. R. (2010). The relationship of ethnicity-related stressors and Latino ethnic identity to well-being. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(3), 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos-Castillo, A. (2006). Negotiating family cultural practices and constructing identities. In Latina girls: Voices of adolescent strength in the US (pp. 44–58). New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, K. A., Capielo Rosario, C., Abreu, R. L., & Cardenas Bautista, E. (2021). “It hurts but it’s the thing we have to do”: Puerto Rican colonial migration. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 9(2), 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, B. C., & Leaper, C. (2025). Ambivalent sexism is linked to Mexican-heritage ethnic identity and gender messages from older relatives, familial peers, and nonfamilial peers. Journal of Latinx Psychology. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, G. G. (2017). Household income: 2016 (American community survey briefs). U.S. Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2017/acs/acsbr16-02.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Guzzardo, M. T., Todorova, I. L. G., Adams, W. E., & Falcón, L. M. (2016). “Half Here, Half There”: Dialogical selves among older puerto ricans of the diaspora. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 29(1), 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, L. W., & Kloska, D. D. (1995). Parents’ gender-based attitudes toward marital roles and child-rearing: Development and validation of new measures. Sex Roles, 32(5–6), 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D., & Johnson, D. (2001). Correlates in children’s experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 981–995. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3599809. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D., Rodriguez, J., Smith, E. P., Johnson, D. J., Stevenson, H. C., & Spicer, P. (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguley, J. P., Wang, M., Vasquez, A. C., & Guo, J. (2019). Parental ethnic–racial socialization practices and the construction of children of color’s ethnic–racial identity: A research synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145(5), 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, P., Kilbourne, B., Reece, M., & Husaini, B. (2008). Community involvement and adolescent mental health: Moderating effects of race/ethnicity and neighborhood disadvantage. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(4), 534–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado, A. (2003). Voicing Chicana feminisms: Young women speak out on sexuality and identity (Vol. 1). nYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S. F., Roche, K. M., Candelaria, A. M., & Ialongo, N. S. (2021). The roles of neighborhood characteristics and parenting in racial/ethnic socialization: Implications for adolescents’ racial identity and adjustment. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(3), 424–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechuga-Peña, S., Brown, S. M., Mitchell, F. M., Becerra, D., & Brisson, D. (2020). Improving parent-child relationships: Effects of your family, your neighborhood intervention. Children and Youth Services Review, 119, 105690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichter, D. T. (2012). Immigration and the new racial diversity in rural America. Rural Sociology, 77(1), 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, M. H., Gonzalez-Barrera, A., & Krogstad, J. M. (2018, October 25). More Latinos have serious concerns about their place in America under Trump. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2018/10/25/more-latinos-have-serious-concerns-about-their-place-in-america-under-trump/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., Meca, A., Unger, J. B., Szapocznik, J., Cano, M. Á., Des Rosiers, S. E., & Schwartz, S. J. (2019). Cultural stress, emotional well-being, and health risk behaviors among recent immigrant Latinx families: The moderating role of perceived neighborhood characteristics. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(1), 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manago, A. M., Ward, L. M., & Aldana, A. (2015). The sexual experience of Latino young adults in college and their perceptions of values about sex communicated by their parents and friends. Emerging Adulthood, 3(1), 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrow, H. (2020). New destination dreaming: Immigration, race, and legal status in the rural American South. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, W., & Polo, A. J. (2018). Neighborhood context, family cultural values, and Latinx youth externalizing problems. J Youth Adolescence, 47, 2440–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. S. (Ed.). (2008). New faces in new places: The changing geography of American immigration. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll, M., & Harkins, A. (2019). Appalachian reckoning: A region responds to Hillbilly Elegy. West Virginia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, A. R., Perez-Brumer, A., & Charlton, B. M. (2023). Latino? Latinx? Latine? A call for inclusive categories in epidemiologic research. American Journal of Epidemiology, 192(12), 1929–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miville, M. L., Mendez, N., & Louie, M. (2017). Latina/o gender roles: A content analysis of empirical research from 1982 to 2013. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 5(3), 173–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, L., Anderson, L. A., O’Brien Caughy, M., Odejimi, O. A., Osborne, K., Suma, K., & Little, T. D. (2024). Changes in ethnic identity in middle childhood: Family and neighborhood determinants. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 44(4), 458–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Immigration Forum. (2025, April 28). First 100 Days: Trump administration roils immigration. Immigration Forum. Available online: https://immigrationforum.org/article/first-100-days-trump-administration-roils-immigration/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Neblett, E. W., Jr., Smalls, C. P., Ford, K. R., Nguyên, H. X., & Sellers, R. M. (2009). Racial socialization and racial identity: African American parents’ messages about race as precursors to identity. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(2), 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyserman, D., & Yoon, K. (2009). Neighborhood effects on racial-ethnic identity: The undermining role of segregation. Race and Social Problems, 1(2), 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Brena, N. J., Bámaca, M. Y., Stein, G. L., & Gomez, E. (2024). Hasta la Raiz: Cultivating racial-ethnic socialization in Latine families. Child Development Perspectives, 18(2), 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Smith, A. M., Albus, K. E., & Weist, M. D. (2001). Exposure to violence and neighborhood affiliation among inner-city youth. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(4), 464–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D. D., & Taylor, R. B. (1996). Ecological assessments of community disorder: Their relationship to fear of crime and theoretical implications. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24(1), 63–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. (2008, February 11). U.S. population projections: 2005–2050. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- Philbin, S. P., & Ayón, C. (2016). Luchamos por nuestros hijos: Latino immigrant parents strive to protect their children from the deleterious effects of anti-immigration policies. Children and Youth Services Review, 63, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, J. S., Horenczyk, G., Liebkind, K., & Vedder, P. (2001). Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: An interactional perspective. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña-Watson, B., Castillo, L. G., Jung, E., Ojeda, L., & Castillo-Reyes, R. (2014). The marianismo beliefs scale: Validation with Mexican American adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(2), 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiros, L., & Dawson, B. A. (2013). The color paradigm: The impact of colorism on the racial identity and identification of Latinas. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23(3), 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffaelli, M., & Ontai, L. L. (2004). Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles, 50(5–6), 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Drake, D. (2012). Ethnic identity and adjustment: The mediating role of sense of community. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(2), 210–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Drake, D., Syed, M., Umaña-Taylor, A., Markstrom, C., French, S., Schwartz, S. J., Lee, R., & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta-analysis of positive ethnic-racial affect and adjustment. Child Development, 85, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, V. P., Cruz, A. C., Bonilla, G. B., Nieves, Y. R., & Ortiz, A. N. (2024). The psychology of Marianismo: A review of empirical research. Salud Y Conducta Humana, 11(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Ruble, D. N., Martin, C. L., & Berenbaum, S. A. (2007). Gender development. In Handbook of child psychology (vol. 3). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, D., Whittaker, L., Hamilton, D. L., & Arango, S. C. (2017). Different types of gendered ethnic-racial socialization: Predicting ethnic identity among Latina/o youth. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 23(4), 527–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, D., Whittaker, T. A., Hamilton, E., & Zayas, L. H. (2016). Perceived discrimination and sexual precursor behaviors in Mexican American preadolescent girls: The role of psychological distress, sexual attitudes, and marianismo beliefs. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(3), 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, K. M., & Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y. (2019). Cultural underpinnings of gender development: Studying gender among children of immigrants. Child Development, 90(4), 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, E., Allen, L., Aber, J. L., Mitchell, C., Feinman, J., Yoshikawa, H., Comtois, K. A., Golz, J., Miller, R. L., Ortiz-Torres, B., & Roper, G. C. (1995). Development and validation of adolescent-perceived microsystem scales: Social support, daily hassles, and involvement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(3), 355–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, R. M., Rowley, S. A. J., Chavous, T. M., Shelton, J. N., & Smith, M. A. (1997). Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and constuct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(4), 805–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, G. L., Coard, S. I., Gonzalez, L. M., Kiang, L., & Sircar, J. K. (2021). One talk at a time: Developing an ethnic-racial socialization intervention for Black, Latinx, and Asian American families. Journal of Social Issues, 77(4), 1014–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G. L., Gonzales, R. G., García Coll, C., & Prandoni, J. I. (2016). Latinos in rural, new immigrant destinations: A modification of the integrative model of child development. In L. J. Crockett, & G. Carlo (Eds.), Rural ethnic minority youth and families in the United States (pp. 37–56). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G. L., Rivas-Drake, D., & Camacho, T. C. (2017). Ethnic identity and familism among Latino college students: A test of prospective associations. Emerging Adulthood, 5(2), 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, E. D. (1973). Marianismo: The other face of machismo in Latin America. In A. Decastello (Ed.), Female and male in Latin America. University of Pittsburg Press. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez Álvarez, J., Pedrosa, I., Lozano, L. M., García-Cueto, E., Cuesta, M., & Muñiz, J. (2018). Using reversed items in Likert scales: A questionable practice. Psicothema, 30(2), 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suárez-Orozco, C., & Suárez-Orozco, M. M. (2001). Children of immigration. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Bámaca, M. Y. (2004). Immigrant mothers’ experiences with ethnic socialization of adolescents growing up in the United States: An examination of Colombian, Guatemalan, Mexican, and Puerto Rican mothers. Sociological Focus, 37(4), 329–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Bhanot, R., & Shin, N. (2006). Ethnic identity formation during adolescence: The critical role of families. Journal of Family Issues, 27(3), 390–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Douglass, S., Updegraff, K. A., & Marsiglia, F. F. (2018). A small-scale randomized efficacy trial of the identity project: Promoting adolescents’ ethnic-racial identity exploration and resolution. Child Development, 89(3), 862–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Hill, N. E. (2020). Ethnic–racial socialization in the family: A decade’s advance on precursors and outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 244–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Quintana, S. M., Lee, R. M., Cross, W. E., Jr., Rivas-Drake, D., Schwartz, S. J., Syed, M., Yip, T., Seaton, E., & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasquez, J. M. (2014). Gender across family generations: Change in Mexican American masculinities and femininities. Identities, 21(5), 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venta, A., Bailey, C. A., Walker, J., Mercado, A., Colunga-Rodriguez, C., Ángel-González, M., & Dávalos-Picazo, G. (2022). Reverse-coded items do not work in Spanish: Data from four samples using established measures. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 828037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. M. B., Nair, R. L., & Bradley, R. H. (2018). Theorizing the benefits and costs of adaptive cultures for development. American Psychologist, 73(6), 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R. M. B., Roosa, M. W., Weaver, S. R., & Nair, R. L. (2009). Cultural and contextual Influences on parenting in Mexican American Families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 71(1), 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: Guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist, 54(8), 594–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M. C. (2020). Latinx parenting in new destinations: Rethinking immigrant family relations [Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill]. Carolina Digital Repository. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, D. P., & Ennett, S. (2011). An examination of social disorganization and pluralistic neighborhood theories with rural mothers and their adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(9), 1243–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, D. P., & Hughes, D. L. (2014). Early adolescent perceptions of neighborhood: Strengths, structural disadvantage, and relations to outcomes. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 34(7), 866–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, D. P., Wei, W., May, E. M., Boggs, S., Chancy, D., Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y., & Bhargava, S. (2021). Latinx youth’s ethnic-racial identity in context: Examining ethnic-racial socialization in a new destination area. Journal of Social Issues, 77(4), 1234–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witherspoon, D. P., White, R. M. B., Bámaca, M. Y., Browning, C. R., Leech, T. G. J., Leventhal, T., Matthews, S. A., Pinchak, N., Roy, A. L., Sugie, N., & Winkler, E. N. (2023). Place-based developmental research: Conceptual and methodological advances in studying youth development in context. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 88(3), 7–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray-Lake, L., Wells, R., Alvis, L., Delgado, S., Syvertsen, A. K., & Metzger, A. (2018). Being a Latinx adolescent under a Trump presidency: Analysis of Latinx youth’s reactions to immigration politics. Children and Youth Services Review, 87, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Hedo, R., Rivera, A., Rull, R., Richardson, S., & Tu, X. M. (2019). Post hoc power analysis: Is it an informative and meaningful analysis? General Psychiatry, 32(4), e100069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parents (N = 60) | Adolescents (N = 60) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 41.06 (9.52) | 13.85 (2.02) | |

| Years living in current neighborhood | 5.8 (7.17) | - | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Puerto Rican | 26 (43.3%) | 24 (40%) | |

| Dominican | 7 (11.7%) | 8 (13.3%) | |

| Mexican | 8 (13.3%) | 7 (11.7%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino/Americana | 8 (13.3%) | 8 (13.3%) | |

| Other | 11 (18.3%) | 13 (21.67%) | |

| Adolescent Sex | |||

| Male | - | 28 (46.7%) | |

| Female | - | 32 (53.3%) | |

| Relation of parent to child | |||

| Mother | 46 (76.7%) | - | |

| Father | 6 (10.0%) | - | |

| Aunt | 2 (3.3%) | - | |

| Grandmother | 2 (3.3%) | - | |

| Other | 4 (6.7%) | - | |

| Parent Education | |||

| Less than high school | 25 (41.7%) | - | |

| High school or equivalent | 14 (23.3%) | - | |

| Some post-secondary education | 17 (28.3%) | - | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4 (6.7%) | - | |

| Marriage/cohabitation status | |||

| Married or cohabitating | 29 (48.3)% | - | |

| Not Married or cohabitating | 18 (30.0%) | - | |

| Divorced or separated | 13 (12.7%) | - | |

| Nativity | |||

| Born outside U.S. 50 states | 52 (86.67%) | 26 (43.3%) | |

| Born in the U.S. | 8 (13.33%) | 34 (56.6%) | |

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent Education | - | |||||||||

| 2. RN Connectedness | −0.12 | - | ||||||||

| 3. RN Problems | −0.02 | −0.40 ** | - | |||||||

| 4. Cultural Socialization (CS) | 0.32 * | 0.01 | −0.00 | - | ||||||

| 5. Prep for Bias (PB) | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.25 † | 0.49 *** | - | |||||

| 6. Promotion of Mistrust (PMT) | −0.09 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.35 ** | - | ||||

| 7. Gender Role Socialization (GRS) | −0.08 | 0.26 * | −0.01 | −0.14 | 0.10 | 0.27 * | - | |||

| 8. Centrality | −0.19 | 0.10 | −00.2 | 0.11 | −0.12 | 0.02 | 0.22 | - | ||

| 9. Private Regard | −0.21 | 0.24 † | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.16 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.64 *** | - | |

| 10. Public Regard | −0.33 * | 0.08 | −0.06 | −0.00 | −0.16 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.60 *** | 0.61 *** | - |

| N | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| M | 2.00 | 2.49 | 1.74 | 3.67 | 3.35 | 1.90 | 1.50 | 3.53 | 4.14 | 3.28 |

| SD | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.72 |

| Min | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.43 | 1.33 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.40 | 2.40 | 1.20 |

| Max | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 3.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Skewness | - | −0.03 | 0.52 | −0.39 | −0.20 | 1.78 | 0.96 | −0.16 | −0.40 | 0.09 |

| Kurtosis | - | −1.17 | −1.35 | −0.63 | −0.50 | 4.09 | −0.11 | −0.58 | −0.44 | 0.42 |

| Parameter Estimates and p Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Variables | Centrality | Private Regard | Public Regard |

| (Intercept) | 4.00 (0.34) *** | 4.33 (0.24) *** | 3.76 (0.25) *** |

| Neighborhood Connectedness | −0.17 (0.14) | 0.12 (0.14) | 0.12 (0.14) |

| Gender Role Socialization (GRS) | 0.30 (0.22) | 0.03 (0.15) | 0.02 (0.17) |

| Neighborhood Connectedness × GRS | −0.17 (0.25) | 0.12 (0.17) | 0.27 (0.18) |

| Child Gender | −0.32 (0.25) | −0.05 (0.18) | −0.17 (0.19) |

| Child Ethnicity | 0.15 (0.25) | 0.11 (0.17) | 0.09 (0.18) |

| Parent Education | −0.20 (0.13) | −0.12 (0.09) | −0.24 (0.10) * |

| N | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.16 |

| adj. R2 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Resid. sd | 0.85 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

| Parameter Estimates and p Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | |

| Variables | Centrality | Private Regard | Public Regard |

| (Intercept) | 4.23 (0.31) *** | 4.41 (0.23) *** | 3.88 (0.25) *** |

| Neighborhood Problems | −0.43 (0.16) * | −0.04 (0.12) | −0.11 (0.13) |

| Gender Role Socialization (GRS) | 0.36 (0.19) † | 0.10 (0.14) | 0.09 (0.15) |

| Neighborhood Problems × GRS | −0.50 (0.26) † | −0.45 (0.19) * | −0.43 (0.20) * |

| Child Gender | −0.57 (0.25) * | −0.10 (0.18) | −0.23 (0.20) |

| Child Ethnicity | 0.00 (0.23) | 0.03 (0.17) | −0.03 (0.18) |

| Parent Education | −0.22 (0.12) † | −0.13 (0.09) | −0.24 (0.09) * |

| N | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| R2 | 0.51 | 0.16 | 0.20 |

| adj. R2 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Resid. sd | 0.85 | 0.63 | 0.68 |

| Outcome | GRS Level | β | SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centrality | −0.50 | −0.18 | 0.21 | [−0.60, 0.24] |

| 0 | −0.43 * | 0.16 | [−0.76, −0.10] | |

| +0.60 | −0.73 ** | 0.22 | [−1.18, −0.28] | |

| Private Regard | −0.50 | 0.19 | 0.15 | [−0.12, 0.50] |

| 0 | −0.04 | 0.12 | [−0.28, 0.20] | |

| +0.60 | −0.32 † | 0.17 | [−0.65, 0.01] | |

| Public Regard | −0.50 | 0.11 | 0.17 | [−0.23, 0.44] |

| 0 | −0.11 | 0.13 | [−0.37, 0.16] | |

| +0.60 | −0.36 † | 0.18 | [−0.72, −0.01] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goldstein, O.C.; Witherspoon, D.P.; Bámaca, M.Y. Neighborhood Conditions in a New Destination Context and Latine Youth’s Ethnic–Racial Identity: What’s Gender Got to Do with It? Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091148

Goldstein OC, Witherspoon DP, Bámaca MY. Neighborhood Conditions in a New Destination Context and Latine Youth’s Ethnic–Racial Identity: What’s Gender Got to Do with It? Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091148

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoldstein, Olivia C., Dawn P. Witherspoon, and Mayra Y. Bámaca. 2025. "Neighborhood Conditions in a New Destination Context and Latine Youth’s Ethnic–Racial Identity: What’s Gender Got to Do with It?" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091148

APA StyleGoldstein, O. C., Witherspoon, D. P., & Bámaca, M. Y. (2025). Neighborhood Conditions in a New Destination Context and Latine Youth’s Ethnic–Racial Identity: What’s Gender Got to Do with It? Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091148