Examining the Effects of Family and Acculturative Stress on Mexican American Parents’ Psychological Functioning as Predictors of Children’s Anxiety and Depression: The Mediating Role of Family Cohesion †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Acculturative Stress and Depression in Mexican American Parents

3. The Link Between Depression and Family Processes

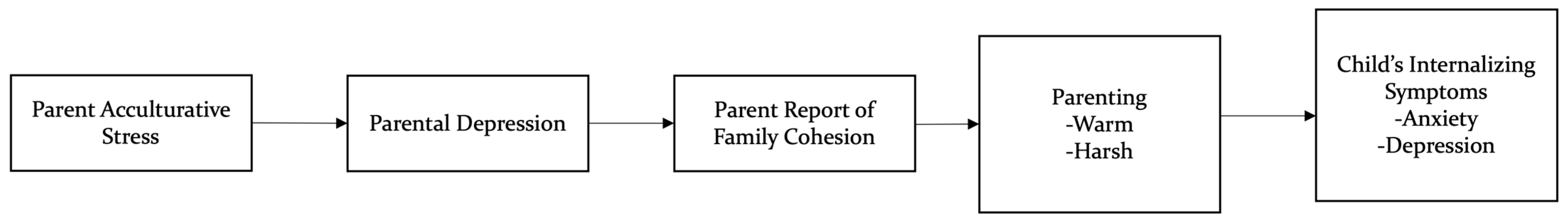

4. Anxiety and Depression in Latino Children

5. The Present Study

- Question 1 (Q1): What is the relationship between parents’ acculturative stress and depression, and subsequently, their reports of family cohesion? What is the role of family cohesion in predicting parenting behaviors and subsequently, children’s internalizing behaviors?

- Question 2 (Q2): What role does family cohesion play in mediating the indirect impact of parental acculturative stress on children’s psychological health?

- Question 3 (Q3): What role does family stress play in predicting the relationships between predictor and dependent variables?

6. Methods

6.1. Participants

6.2. Procedure

6.3. Instruments

6.3.1. General Family Stress

6.3.2. Acculturative Stress

6.3.3. Parental Psychological Functioning

6.3.4. Family Cohesion

6.3.5. Parenting Processes

6.3.6. Youth’s Internalizing Symptoms

6.4. Analytic Plan

7. Results

7.1. Correlational Analyses

7.2. Measurement Models

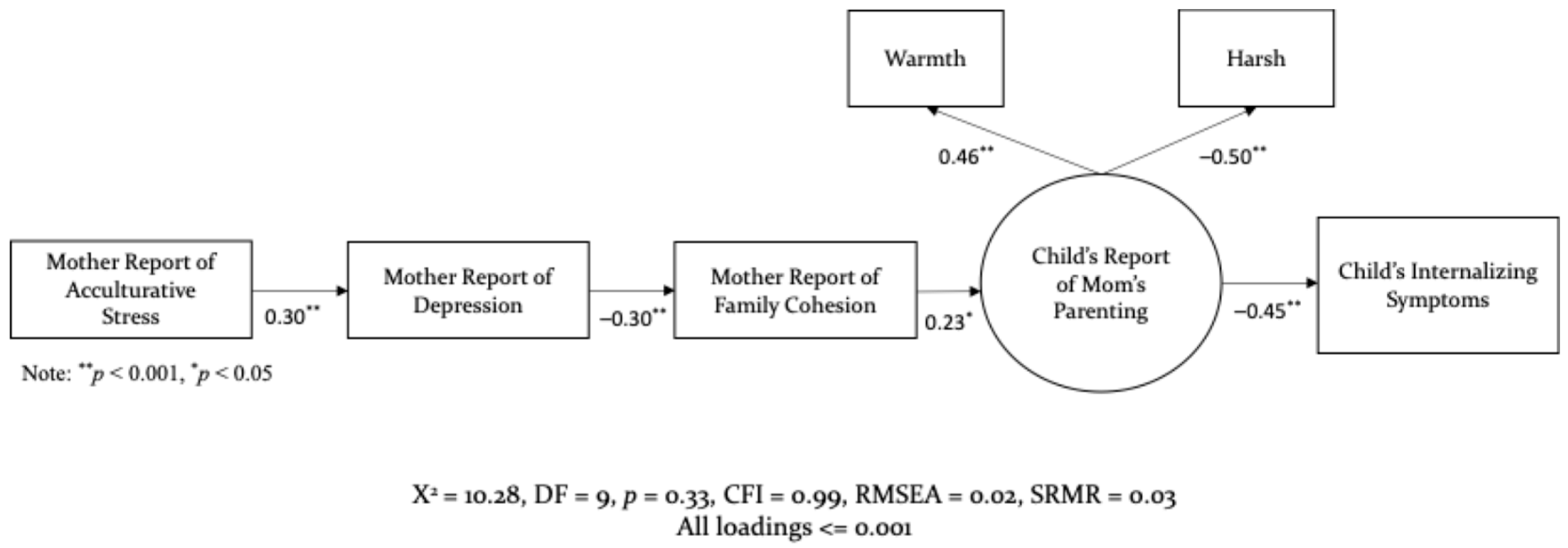

7.2.1. Mothers’ Model

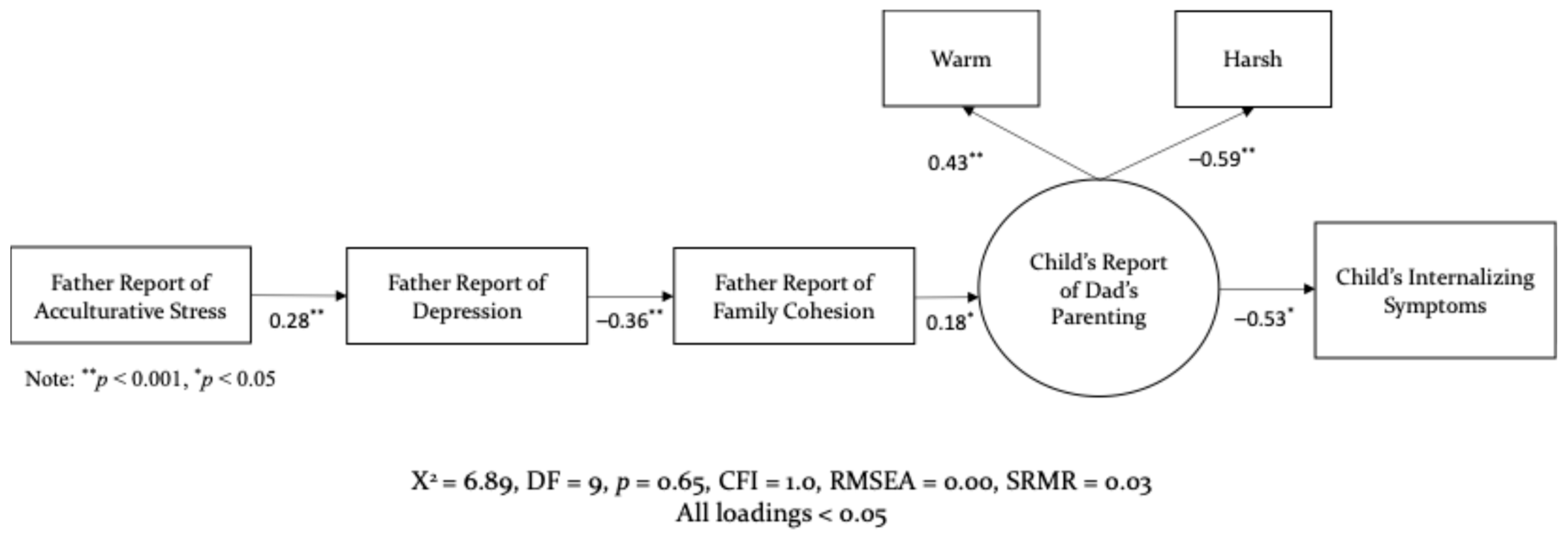

7.2.2. Fathers’ Model

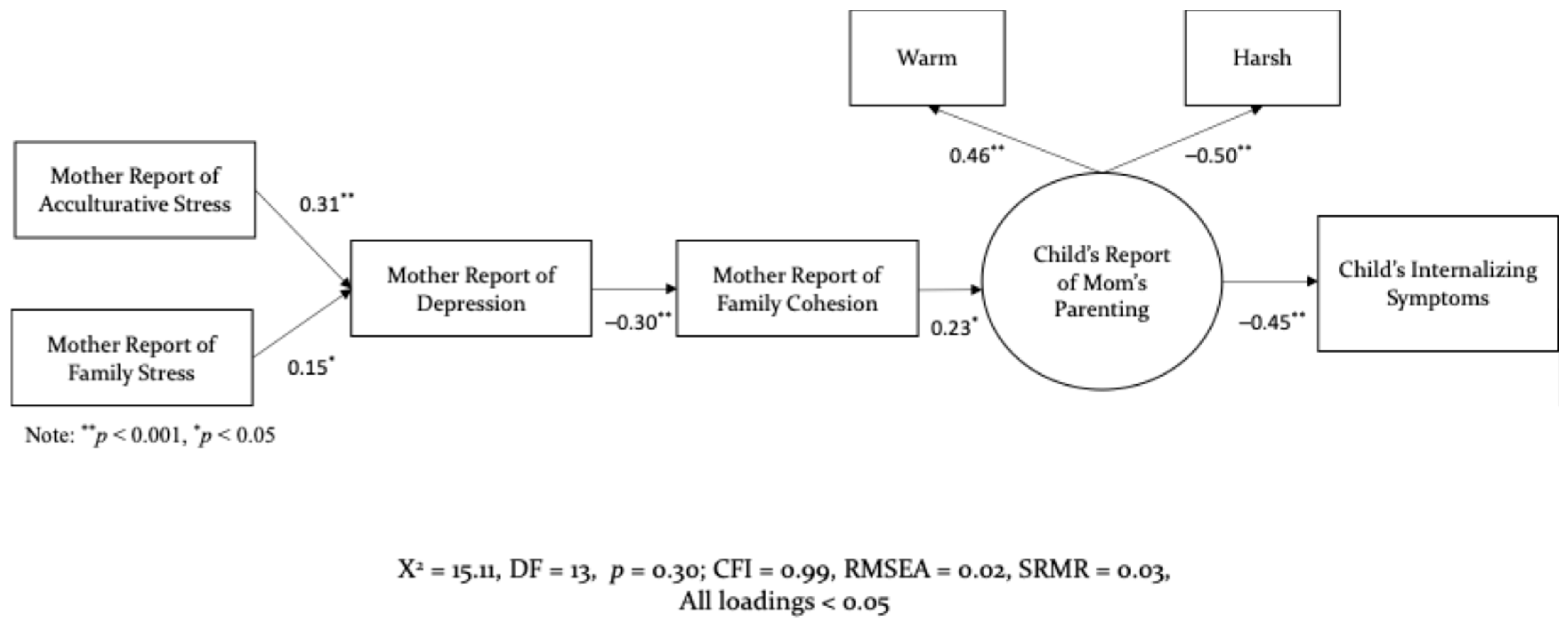

7.2.3. Full Structural Models

8. Discussion

8.1. Mothers and Fathers Pathways (Q1)

8.2. The Mediating Role of Family Cohesion (Q2)

8.3. The Role of General Family Stress (Q3)

9. Implications

10. Limitations and Future Directions

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akoglu, H. (2018). User’s guide to correlation coefficients. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 18(3), 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Y. A., Hussein, R. S., Mostafa, N. S., & Manzour, A. F. (2024). Factors associated with acculturative stress among international medical students in an Egyptian university. BMC Medical Education, 24(1), 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J., Biello, K. B., Pedraza, F., Wintner, S., & Viruell-Fuentes, E. (2016). The association between anti-immigrant policies and perceived discrimination among Latinos in the US: A multilevel analysis. SSM-Population Health, 2, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbinder, T. (2019, November 8). Trump has spread more hatred of immigrants than any American in history. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/trump-has-spread-more-hatred-of-immigrants-than-any-american-in-history/2019/11/07/7e253236-ff54-11e9-8bab-0fc209e065a8_story.html (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Arbuckle, J. L., & Wothke, W. (1999). Amos 4.0 user’s guide. SmallWaters Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Ayón, C., & Becerra, D. (2013). Mexican immigrant families under siege: The impact of anti-immigrant policies, discrimination, and the economic crisis. Advances in Social Work, 14(1), 206–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayón, C., Valencia-Garcia, D., & Kim, S. H. (2017). Latino immigrant families and restrictive immigration climate: Perceived experiences with discrimination, threat to family, social exclusion, children’s vulnerability, and related factors. Race and Social Problems, 9(4), 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basáñez, T., Unger, J. B., Soto, D., Crano, W., & Baezconde-Garbanati, L. (2013). Perceived discrimination as a risk factor for depressive symptoms and substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Los Angeles. Ethnicity & Health, 18(3), 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Gayles, J. G. (2012). A developmental-contextual model of depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, A. O., MacDermid, S. M., Coltrane, S. L., Parke, R. D., Duffy, S., & Widaman, K. F. (2008). Family cohesion in the lives of Mexican American and European American parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70(4), 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K. (2020). Reserve capacity model. In Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences (pp. 4435–4437). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (1998). Acculturative stress. In P. B. Organista, K. M. Chun, & G. Marin (Eds.), Readings in ethnic psychology (pp. 117–122). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. W. (2008). Globalisation and acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 32(4), 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W., & Annis, R. C. (1974). Acculturative stress: The role of ecology, culture and differentiation. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 5(4), 382–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørndal, L. D., Ebrahimi, O. V., Røysamb, E., Karstoft, K. I., Czajkowski, N. O., & Nes, R. B. (2024). Stressful life events exhibit complex patterns of associations with depressive symptoms in two population-based samples using network analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 349, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S. (2019). The essential role of the father: Fostering a father-inclusive practice approach with immigrant and refugee families. Journal of Family Social Work, 22(1), 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, M., Woodbury-Fariña, M., Canino, G. J., & Rubio-Stipec, M. (1993). The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) in Puerto Rico. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 17(3), 329–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N. J., Alonso, A., & Chen, Y. (2021). Parenting contributions to Latinx children’s development in the early years. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 696(1), 158–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, E. J., Barajas-Gonzalez, R. G., Huang, K. Y., & Brotman, L. (2017). Early childhood internalizing problems in Mexican-and Dominican-origin children: The role of cultural socialization and parenting practices. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(4), 551–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calzada, E. J., & Sales, A. (2019). Depression among Mexican-origin mothers: Exploring the immigrant paradox. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(2), 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calzada, E. J., Sales, A., & O’Gara, J. L. (2019). Maternal depression and acculturative stress impacts on Mexican-origin children through authoritarian parenting. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 63, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho-Gonsalves, T. (2002). Depressive symptomatology among Dominicans: Links to acculturative and economic stressors, skin tone, and perceived discrimination [Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation]. University of New Hampshire.

- Caplan, S. (2007). Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: A dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 8(2), 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, J., Scott, J. L., Faulkner, M., & Barros Lane, L. (2018). Parenting in the context of deportation risk. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(2), 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauce, A. M., Ryan, K. D., & Grove, K. (1998). Children and adolescents of color, where are you? Participation, selection, recruitment, and retention in developmental research. In V. C. McLoyd, & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Studying minority adolescents: Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical issues (pp. 147–166). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, R. C., Gattamorta, K. A., & Berger-Cardoso, J. (2019). Examining difference in immigration stress, acculturation stress and mental health outcomes in six Hispanic/Latino nativity and regional groups. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(1), 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, B. Y., Chudek, M., & Heine, S. J. (2010). Evidence for a sensitive period for acculturation: Younger immigrants report acculturating at a faster rate. Psychological Science, 22(2), 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, R. D., Ge, X., Elder, G. H., Jr., Lorenz, F. O., & Simons, R. L. (1994). Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Development, 65(2), 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, E. M., Goeke-Morey, M. C., Raymond, J., & Lamb, M. E. (2004). Fathers in family context: Effects of marital quality and marital conflict. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development (5th ed., pp. 196–221). John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- D’Anna-Hernandez, K. L., Aleman, B., & Flores, A. M. (2015). Acculturative stress negatively impacts maternal depressive symptoms in Mexican-American women during pregnancy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 176, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deater-Deckard, K. (2004). Parenting stress. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131(4), 483–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmen, R. A., Malda, M., Mesman, J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Prevoo, M. J., & Yeniad, N. (2013). Socioeconomic status and parenting in ethnic minority families: Testing a minority family stress model. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(6), 896–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figge, C. J., Martinez-Torteya, C., & Kosson, D. S. (2020). Parent cultural stress and internalizing problems in Latinx preschoolers: Moderation by maternal involvement and positive verbalizations. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 23(5), 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanti, G. A. (2003). The Hispanic family and male-female relationships: An overview. Journal of Trascultural Nursing: Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society, 14(3), 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A. G., Vega, W. A., & Dimas, J. M. (1994). Acculturative stress and personal adjustment among Hispanic adolescent boys. Journal of Community Psychology, 22(1), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, N. A., Tein, J., Sandler, I. N., & Friedman, R. J. (2001). On the limits of coping: Interactions between stress and coping for inner-city adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 16, 372–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R. A., & Santos, H. P., Jr. (2020). Maternal depression in Latinas and child socioemotional development: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 15(3), e0230256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovey, J. D., & King, C. A. (1996). Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1183–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, S. C., Silberberg, M., Hartmann, K. E., & Michener, J. L. (2010). Perceived discrimination and use of health care services in a North Carolina population of Latino immigrants. Hispanic Health Care International, 8(1), 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiderra, I. (2022, September 12). More stress, fewer coping resources for Latina mothers post-Trump. UC San Diego Today. Available online: https://today.ucsd.edu/story/more-stress-fewer-coping-resources-for-latina-mothers-post-trump (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, G. P., Virdin, L. M., & Roosa, M. (1994). Socialization and family correlates of mental health outcomes among Hispanic and Anglo-American children: Consideration of cross-ethnic scalar equivalence. Child Development, 65(1), 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogstad, J. M., Passel, J. S., & Noe-Bustamante, L. (2023, September 22). Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage month. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2022/09/23/key-facts-about-u-s-latinos-for-national-hispanic-heritage-month/ (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Leidy, M. S., Guerra, N. G., & Toro, R. I. (2010). Positive parenting, family cohesion, and child social competence among immigrant Latino families. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(3), 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, A. L. (2014). Immigration and stress: The relationship between parents’ acculturative stress and young children’s anxiety symptoms. Student Pulse, 6(3). Available online: http://www.studentpulse.com/a?id=861 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Lopez, M., Gonzalez-Barrera, A., & Krogstad, J. (2020, August 27). Latinos’ experiences with discrimination. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2018/10/25/latinos-and-discrimination/ (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., Meca, A., Unger, J. B., Romero, A., Gonzales-Backen, M., Piña-Watson, B., Cano, M. Á., Zamboanga, B. L., Rosiers, S. E. D., Soto, D. W., Villamar, J. A., Lizzi, K. M., Pattarroyo, M., & Schwartz, S. J. (2016). Latino parent acculturation stress: Longitudinal effects on family functioning and youth emotional and behavioral health. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(8), 966–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. A., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 561–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, A., Cervantes, R. C., Estrada, Y., & Prado, G. (2022). Impacts of acculturative, parenting, and family stress on US born and immigrant Latina/o/x parent’s mental health and substance use. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 25(2), 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lueck, K., & Wilson, M. (2011). Acculturative stress in Latino immigrants: The impact of social, socio-psychological and migration-related factors. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35(2), 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manongdo, J. A., & Ramirez Garcia, J. I. (2007). Mothers’ parenting dimensions and adolescent externalizing and internalizing behaviors in a low-income, urban Mexican American sample. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(4), 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsiglia, F. F., Parsai, M., & Kulis, S. (2009). Effects of familism and family cohesion on problem behaviors among adolescents in Mexican immigrant families in the southwest United States. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 18(3), 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, A. L., Draucker, C. B., & Bigatti, S. (2019). Cultural stressors and depressive symptoms in Latino/a adolescents: An integrative review. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 25(1), 49–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, B. D., Wood, J. J., & Weisz, J. R. (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(2), 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWhirter, A. C., & Donovick, M. R. (2022). Acculturation, parenting stress, and children’s problem behaviours among immigrant Latinx mothers and fathers. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 32(5), 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mental Health America. (2021). Latinx/Hispanic communities and mental health. Available online: https://mhanational.org/position-statements/latinx-hispanic-communities-and-mental-health/ (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Miller, M., & Csizmadia, A. (2022). Applying the family stress model to parental acculturative stress and Latinx youth adjustment: A review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 14, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, V. M., Brown, P. A., Brody, G. H., Cutrona, C. E., & Simons, R. L. (2004). Racial discrimination as a moderator of the links among stress, maternal psychological functioning, and family relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(4), 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, V. M., Butler-Barnes, S. T., Mayo-Gamble, T. L., & Inniss-Thompson, M. N. (2018). Excavating new constructs for family stress theories in the context of everyday life experiences of Black American families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(2), 384–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D. H., Portner, J., & Bell, R. (1983). FACES II: Family adaptability and cohesion scales 1982 [Master’s thesis, Kansas State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Preciado, A., & D’Anna-Hernandez, K. (2017). Acculturative stress is associated with trajectory of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy in Mexican-American women. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 48, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, K. M., Vaquera, E., White, R. M. B., & Rivera, M. I. (2018). Impacts of immigration actions and news and the psychological distress of US Latino parents raising adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(5), 525–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, A. C. I., Polcari, J. J., Nephew, B. C., Harris, R., Zhang, C., Murgatroyd, C., & Santos, H. P., Jr. (2022). Acculturative stress, telomere length, and postpartum depression in Latinx mothers. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 147, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosa, M. W., Liu, F. F., Torres, M., Gonzales, N. A., Knight, G. P., & Saenz, D. (2008). Sampling and recruitment in studies of cultural influences on adjustment: A case study with Mexican Americans. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R., & Rubin, D. B. (1979). A note on percent variance explained as a measure of the importance of effects. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 9(5), 395–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothenberg, W. A., Ali, S., Rohner, R. P., Lansford, J. E., Britner, P. A., Di Giunta, L., Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Oburu, P., Pastorelli, C., Skinner, A. T., Sorbring, E., Steinberg, L., Tapanya, S., Tirado, L. M. U., Yotanyamaneewong, S., Alampay, L. P., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., … Deater-Deckard, K. (2022). Effects of parental acceptance-rejection on children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors: A longitudinal, multicultural study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(1), 29–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, L. M., Ayón, C., & Gurrola, M. (2013). Estamos traumados: The effect of anti-immigrant sentiment and policies on the mental health of Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(8), 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas-Wright, C. P., Maldonado-Molina, M. M., Brown, E. C., Bates, M., Rodríguez, J., García, M. F., & Schwartz, S. J. (2021). Cultural stress theory in the context of family crisis migration: Implications for behavioral health with illustrations from the Adelante Boricua Study. American Journal of Criminal Justice: AJCJ, 46(4), 586–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Wright, C. P., & Schwartz, S. J. (2019). The study and prevention of alcohol and other drug misuse among migrants: Toward a transnational theory of cultural stress. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(2), 346–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, E. S. (1965). A configurational analysis of children’s reports of parent behavior. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 29(6), 552–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitt, N. (1996). Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment, 8(4), 350–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, K., Fielding, B., & Wendt, D. (2017). Similarities and differences in the influence of paternal and maternal depression on adolescent well-being. Social Work Research, 41(2), 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Lucas, C. P., Dulcan, M. K., & Schwab-Stone, M. E. (2000). NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(1), 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L., Driscoll, M. W., & Voell, M. (2012). Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: A moderated mediational model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(1), 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roy, B., Groholt, B., Heyerdahl, S., & Clench-Aas, J. (2010). Understanding discrepancies in parent-child reporting of emotional and behavioural problems: Effects of relational and socio-demographic factors. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, J. (2019, August 21). Trump’s anti-immigrant ‘invasion’ rhetoric was echoed by the El Paso shooter for a reason. NBC News Think. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/think/opinion/trump-s-anti-immigrant-invasion-rhetoric-was-echoed-el-paso-ncna1039286 (accessed on 16 November 2023).

- Vargas, E. D., Sanchez, G. R., & Juárez, M. (2017). Fear by association: Perceptions of anti-immigrant policy and health outcomes. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 42(3), 459–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, W. A., Gil, A. G., Warheit, G. J., Zimmerman, R. S., & Apospori, E. (1993). Acculturation and delinquent behavior among Cuban American adolescents: Toward an empirical model. American Journal of Community Psychology, 21(1), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, C. (2006). Acculturation, identity, and adaptation in dual heritage adolescents. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(2), 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. M. B., Liu, Y., Nair, R. L., & Tein, J. Y. (2015). Longitudinal and integrative tests of family stress model effects on Mexican origin adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 649–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, R. M. B., & Roosa, M. W. (2012). Neighborhood contexts, fathers, and Mexican American young adolescents’ internalizing symptoms. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. M. B., Roosa, M. W., Weaver, S. R., & Nair, R. L. (2009). Cultural and contextual influences on parenting in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(6), 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wray-Lake, L., Wells, R., Alvis, L., Delgado, S., Syvertsen, A. K., & Metzger, A. (2018). Being a Latinx adolescent under a Trump presidency: Analysis of Latinx youth’s reactions to immigration politics. Children and Youth Services Review, 87, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiders, K. H., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Updegraff, K. A., & Jahromi, L. B. (2015). Acculturative and enculturative stress, depressive symptoms, and maternal warmth: Examining within-person relations among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 27(1), 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Family Stress | ---- | ||||||||

| 2. Acculturative Stress | −0.09 | ---- | |||||||

| 3. Depression | 0.12 ** | 0.28 ** | ---- | ||||||

| 4. Family Cohesion | −0.04 | −0.12 * | −0.30 ** | ---- | |||||

| 5. Warm Parenting (M) | 0.05 | 0.05 | −0.06 | 0.38 ** | ---- | ||||

| 6. Warm Parenting (C) | 0.06 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.17 ** | 0.18 ** | ---- | |||

| 7. Harsh Parenting (M) | 0.13 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.08 | ---- | ||

| 8. Harsh Parenting (C) | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.11 * | −0.13 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.21 ** | ---- | |

| 9. Internalizing Symptoms | −0.02 | −0.08 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −0.07 | −0.20 ** | 0.05 | 0.24 ** | ---- |

| Mean | 1.27 | 2.43 | 1.71 | 4.02 | 4.37 | 4.17 | 2.11 | 2.02 | 3.30 |

| SD | 1.20 | 1.19 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.74 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 2.68 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Acculturative Stress | ---- | |||||||

| 2. Depression | 0.27 ** | ---- | ||||||

| 3. Family Cohesion | −0.15 ** | −0.35 ** | ---- | |||||

| 4. Warm Parenting (F) | −0.10 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.49 ** | ---- | ||||

| 5. Warm Parenting (C) | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.09 | 0.16 ** | ---- | |||

| 6. Harsh Parenting (F) | 0.21 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.06 | −0.12 * | −0.12 * | ---- | ||

| 7. Harsh Parenting (C) | 0.04 | 0.07 | −0.13 * | −0.11 * | −0.25 ** | 0.22 ** | ---- | |

| 8. Internalizing Symptoms | 0.01 | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.09 | −0.21 ** | 0.02 | 0.26 ** | ---- |

| Mean | 1.99 | 1.54 | 3.96 | 4.20 | 3.99 | 1.93 | 1.87 | 3.30 |

| SD | 0.95 | 0.43 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 2.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gonzalez-Detrés, C.M.; Murry, V.M.; Gonzales, N.A. Examining the Effects of Family and Acculturative Stress on Mexican American Parents’ Psychological Functioning as Predictors of Children’s Anxiety and Depression: The Mediating Role of Family Cohesion. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081098

Gonzalez-Detrés CM, Murry VM, Gonzales NA. Examining the Effects of Family and Acculturative Stress on Mexican American Parents’ Psychological Functioning as Predictors of Children’s Anxiety and Depression: The Mediating Role of Family Cohesion. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081098

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzalez-Detrés, Catherine Myshell, Velma McBride Murry, and Nancy A. Gonzales. 2025. "Examining the Effects of Family and Acculturative Stress on Mexican American Parents’ Psychological Functioning as Predictors of Children’s Anxiety and Depression: The Mediating Role of Family Cohesion" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081098

APA StyleGonzalez-Detrés, C. M., Murry, V. M., & Gonzales, N. A. (2025). Examining the Effects of Family and Acculturative Stress on Mexican American Parents’ Psychological Functioning as Predictors of Children’s Anxiety and Depression: The Mediating Role of Family Cohesion. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1098. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081098