The Relationship Between the Big Five Personality Model and Innovation Behavior: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Big Five Model and Innovation Behavior

2.2. Moderators

2.2.1. Cultural Context

2.2.2. Sample Type

2.2.3. Gender Differences

2.2.4. Personality Measurement Types

3. Method

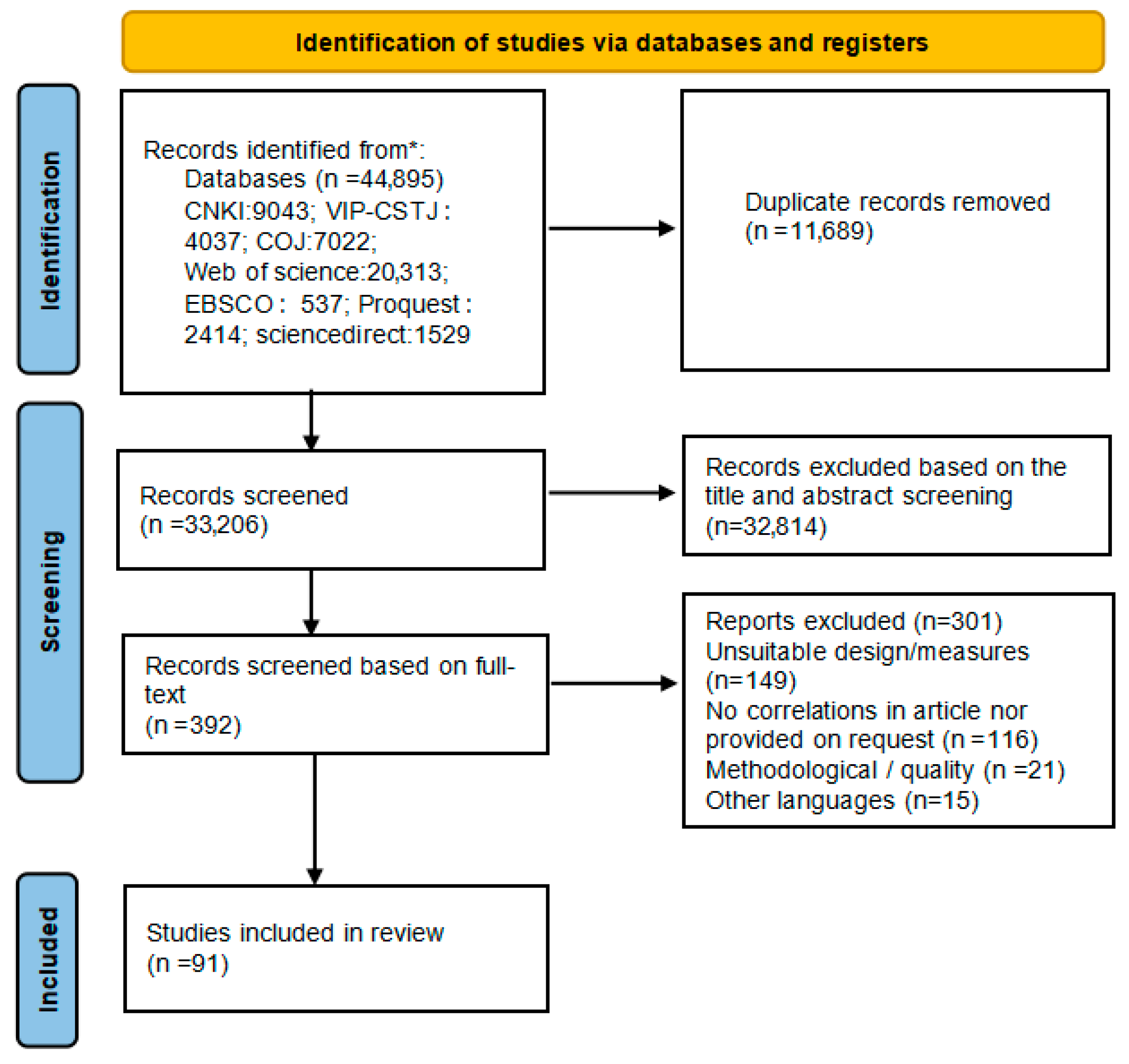

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

3.3. Data Extraction

3.4. Data Analytic Approach

4. Results

4.1. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.2. Publication Bias

4.3. Overall Effect Size

4.4. Moderator Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Limitations and Future Research

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akbari, M., Bagheri, A., Imani, S., & Asadnezhad, M. (2021). Does entrepreneurial leadership encourage innovation work behavior? The mediating role of creative self-efficacy and support for innovation. European Journal of Innovation Management, 24(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglim, J., Dunlop, P. D., Wee, S., Horwood, S., Wood, J. K., & Marty, A. (2022). Personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 148(5–6), 301–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appio, F. P., Frattini, F., Petruzzelli, A. M., & Neirotti, P. (2021). Digital transformation and innovation management: A synthesis of existing research and an agenda for future studies. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assink, M., & Wibbelink, C. J. (2016). Fitting three-level meta-analytic models in R: A step-by-step tutorial. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 12(3), 154–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, M., De Dreu, C. K., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: Hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychological Bulletin, 134(6), 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, M., & Oldham, G. R. (2006). The curvilinear relation between experienced creative time pressure and creativity: Moderating effects of openness to experience and support for creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batey, M., Chamorro-Premuzic, T., & Furnham, A. (2010). Individual differences in ideational behavior: Can the big five and psychometric intelligence predict creativity scores? Creativity Research Journal, 22(1), 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, F., Gao, Y., & Sousa, C. M. (2013). A natural science approach to investigate cross-cultural managerial creativity. International Business Review, 22(5), 839–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D. S., Oh, I.-S., Berry, C. M., Li, N., & Gardner, R. G. (2011). The five-factor model of personality traits and organizational citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.-y., & Kwan, L. Y. (2010). Culture and creativity: A process model. Management and Organization Review, 6(3), 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmarchelier, B., & Fang, E. S. (2016). National culture and innovation diffusion. Exploratory insights from agent-based modeling. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 105, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeYoung, C. G., Quilty, L. C., & Peterson, J. B. (2007). Between facets and domains: 10 aspects of the big five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5), 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the big five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18(2), 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot–based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics, 56(2), 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Castilla, B., Declercq, L., Jamshidi, L., Beretvas, S. N., Onghena, P., & Van den Noortgate, W. (2021). Detecting selection bias in meta-analyses with multiple outcomes: A simulation study. The Journal of Experimental Education, 89(1), 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fürst, G., Ghisletta, P., & Lubart, T. (2016). Toward an integrative model of creativity and personality: Theoretical suggestions and preliminary empirical testing. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 50(2), 87–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajzel, K., Acar, S., & Singer, G. (2023). The big five and divergent thinking: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 214, 112338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1967). Creativity: Yesterday, today and tomorrow. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 1(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. (2020). Relationships between leadership, motivation and employee-level innovation: Evidence from India. Personnel Review, 49(7), 1363–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, S. J. (2001). Self as cultural product: An examination of East Asian and North American selves. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 881–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, R., & Vetter, D. E. (1996). An empirical comparison of published replication research in accounting, economics, finance, management, and marketing. Journal of Business Research, 35(2), 153–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big-five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102–138). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, E. D., & Zhang, D. C. (2021). Personality profile of risk-takers. Journal of Individual Differences, 42, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2013). Do people recognize the four Cs? Examining layperson conceptions of creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 7(3), 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, S. B., Quilty, L. C., Grazioplene, R. G., Hirsh, J. B., Gray, J. R., Peterson, J. B., & DeYoung, C. G. (2016). Openness to experience and intellect differentially predict creative achievement in the arts and sciences. Journal of Personality, 84(2), 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, L. A., Walker, L. M., & Broyles, S. J. (1996). Creativity and the five-factor model. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(2), 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, J., & Hu, B. (2017). The influence of non-cognitive ability on workers’ wage income. Chinese Journal of Population Science, (04), 66–76+127. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K., & Ashton, M. C. (2020). Sex differences in HEXACO personality characteristics across countries and ethnicities. Journal of Personality, 88(6), 1075–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y., Chen, C., Zhu, N., Zhang, J., & Wang, S. (2020). How does “one takes on the attributes of one’s associates”? The past, present, and future of trait activation theory. Advances in Psychological Science, 28(1), 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammadov, S. (2022). Big Five personality traits and academic performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality, 90(2), 222–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R., & Terracciano, A. (2005). Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: Data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(3), 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. The Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowen, J. C. (2000). The 3M model of motivation and personality: Theory and empirical applications to consumer behavior. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Muraven, M., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., & Brennan, S. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, A. M., Arnone, D., Smallwood, J., & Mobbs, D. (2015). Thinking too much: Self-generated thought as the engine of neuroticism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19(9), 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poropat, A. E. (2009). A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychological Bulletin, 135(2), 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, U., & Johns, G. (2010). The joint effects of personality and job scope on in-role performance, citizenship behaviors, and creativity. Human Relations, 63(7), 981–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammstedt, B., & John, O. P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the big five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, J., Pace, V. L., & Frese, M. (2004). Three avenues for future research on creativity, innovation, and initiative. Applied Psychology, 53(4), 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B. W., Lejuez, C., Krueger, R. F., Richards, J. M., & Hill, P. L. (2014). What is conscientiousness and how can it be assessed? Developmental Psychology, 50(5), 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M. A., & Pustejovsky, J. E. (2021). Evaluating meta-analytic methods to detect selective reporting in the presence of dependent effect sizes. Psychological Methods, 26(2), 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, P. L., Le, H., Oh, I.-S., Van Iddekinge, C. H., & Bobko, P. (2018). Using beta coefficients to impute missing correlations in meta-analysis research: Reasons for caution. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(6), 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Ruiz, M.-J., Romo Santos, M., & Jimenez Jimenez, J. (2013). The role of metaphorical thinking in the creativity of scientific discourse. Creativity Research Journal, 25(4), 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a theory of the universal content and structure of values: Extensions and cross-cultural replications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J., & Geng, R. (2020). Research on the relations among knowledge sharing, intellectual capital and innovation capability of think tanks. Information Science, 38(6), 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvia, P. J., Kaufman, J. C., Reiter-Palmon, R., & Wigert, B. (2011). Cantankerous creativity: Honesty–humility, agreeableness, and the HEXACO structure of creative achievement. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(5), 687–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, G. D., Rinne, T., & Fairweather, J. (2012). Personality, nations, and innovation: Relationships between personality traits and national innovation scores. Cross-Cultural Research, 46(1), 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockemer, D., & Sundström, A. (2016). Modernization theory: How to measure and operationalize it when gauging variation in women’s representation? Social Indicators Research, 125(2), 695–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C. L., Said-Metwaly, S., Camarda, A., & Barbot, B. (2024). Gender differences and variability in creative ability: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the greater male variability hypothesis in creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 126(6), 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M. Z., & Wilson, S. (2012). Does culture still matter?: The effects of individualism on national innovation rates. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(2), 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. (2018). Social capital, innovation and economic growth. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 73, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Noortgate, W., & Onghena, P. (2003). Multilevel meta-analysis: A comparison with traditional meta-analytical procedures. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63(5), 765–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viechtbauer, W. (2010). Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software, 36, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswesvaran, C., & Ones, D. S. (1995). Theory testing: Combining psychometric meta-analysis and structural equations modeling. Personnel Psychology, 48(4), 865–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Lan, Y., & Li, C. (2022). Challenge-hindrance stressors and innovation: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(4), 761–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Yi, M. (2022). Complex humanity: Configurational paths of personality traits to innovative behavior. Research and Development Management, 34(3), 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, X., Meng, Q., Yao, C., Lv, X., & Guo, H. (2020). The Relationship between Conscientiousness and Entrepreneurial Performance: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 26(3), 282–288. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y., & Han, S. (2013). A study on relationship between effects of the organizational justice and personality traits on employee’ innovative behavior. Chinese Journal of Management, 10(5), 700–707. [Google Scholar]

- Zare, M., & Flinchbaugh, C. (2019). Voice, creativity, and big five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Human Performance, 32(1), 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W., Huang, T., Zhang, Y., Tan, Z., & Guo, Q. (2023). The big five personality traits and Chinese people’s subjective well-being: A meta-analysis of recent indigenous studies in more than 20 years. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(3), 714–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | k | #es | N | r | t | 95%CI | %Var.at Level 1 | %Var.at Level 2 | %Var.at Level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | 48 | 68 | 18,286 | 0.116 * | 2.459 | [0.022, 0.211] | 2.096 | 4.176 | 93.728 |

| Extraversion | 53 | 73 | 19,039 | 0.351 *** | 10.700 | [0.286, 0.417] | 4.305 | 15.006 | 80.688 |

| Openness | 77 | 102 | 28,875 | 0.406 *** | 14.685 | [0.31, 0.461] | 4.41 | 13.956 | 81.635 |

| Conscientiousness | 61 | 83 | 22,253 | 0.292 *** | 8.566 | [0.224, 0.36] | 3.566 | 9.409 | 87.024 |

| Neuroticism | 53 | 73 | 19,143 | −0.083 | −2.066 | [−0.163, −0.003] | 2.862 | 9.524 | 87.613 |

| Moderator | QE(df) | F(df1, df2) | r | SE | 95%CI | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | Cultural context (Individualism) | QE(57) = 1146.122 *** | F(1, 57) = 0.885 *** | 0.156 | 0.036 | [0.083, 0.228] | 4.312 |

| Extraversion | Cultural context (Individualism) | QE(62) = 123.391 *** | F(1, 62) = 0.275 *** | 0.368 | 0.035 | [0.298, 0.439] | 10.465 |

| Openness | Cultural context (Individualism) | QE(88) = 1604.224 *** | F(1, 88) = 0.000 *** | 0.398 | 0.030 | [0.339, 0.457] | 13.382 |

| Conscientiousness | Cultural context (Individualism) | QE(32) = 474.630 *** | F(1, 70) = 2.003 *** | 0.309 | 0.047 | [0.237, 0.382] | 8.507 |

| Neuroticism | Cultural context (Individualism) | QE(62) = 1639.618 *** | F(1, 62) = 0.458 | −0.082 | 0.044 | [−0.170, 0.006] | −1.867 |

| Moderator | QE(df) | F(df1, df2) | r | SE | 95%CI | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | Sample type | QE(55) = 941.155 *** | F(1, 55) = 0.819 ** | ||||

| Employee | 0.217 | 0.069 | [−0.235, 0.354] | 3.161 | |||

| Students | 0.144 | 0.042 | [0.059, 0.229] | 3.385 | |||

| Extraversion | Sample type | QE(60) = 1025.024 *** | F(1, 60) = 0.103 *** | ||||

| Employee | 0.380 | 0.062 | [0.257, 0.504] | 6.173 | |||

| Students | 0.356 | 0.043 | [0.270, 0.443] | 8.224 | |||

| Openness | Sample type | QE(89) = 1580.689 *** | F(1, 89) = 6.527 *** | ||||

| Employee | 0.340 | 0.040 | [0.261, 0.418] | 8.575 | |||

| Students | 0.480 | 0.038 | [0.404, 0.557] | 12.538 | |||

| Conscientiousness | Sample type | QE(70) = 1530.131 *** | F(1, 70) = 0.226 *** | ||||

| Employee | 0.326 | 0.056 | [0.215, 0.437] | 5.849 | |||

| Students | 0.291 | 0.048 | [0.196, 0.386] | 6.087 | |||

| Neuroticism | Sample type | QE(60) = 1543.681 *** | F(1, 60) = 0.713 | ||||

| Employee | −0.033 | 0.076 | [−0.184, 0.119] | −0.431 | |||

| Students | −0.111 | 0.053 | [−0.217, −0.005] | −2.086 |

| Moderator | QE(df) | F(df1, df2) | r | SE | 95%CI | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | Gender (Female %) | QE(59) = 4858.455 *** | F(1, 59) = 3.374 * | 0.123 | 0.050 | [0.023, 0.224] | 2.448 |

| Extraversion | Gender (Female %) | QE(64) = 1159.998 *** | F(1, 64) = 2.867 *** | 0.333 | 0.032 | [0.269, 0.387] | 10.422 |

| Openness | Gender (Female %) | QE(91) = 1888.765 *** | F(1, 91) = 0.488 *** | 0.414 | 0.030 | [0.355, 0.473] | 13.923 |

| Conscientiousness | Gender (Female %) | QE(72) = 1543.624 *** | F(1, 72) = 0.039 *** | 0.296 | 0.035 | [0.227, 0.365] | 8.517 |

| Neuroticism | Gender (Female %) | QE(63) = 1702.415 *** | F(1, 63) = 0.352 * | −0.095 | 0.045 | [−0.184, −0.006] | −2.141 |

| Moderator | QE(df) | F(df1, df2) | r | SE | 95%CI | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | Personality Measurement | QE(63) = 4999.632 *** | F(1, 63) = 0.264 | ||||

| NEO | 0.128 | 0.074 | [−0.019, 0.275] | 1.737 | |||

| IPIP | 0.026 | 0.108 | [−0.190, 0.242] | 0.241 | |||

| TIPI | 0.166 | 0.155 | [−0.144, 0.475] | 1.071 | |||

| BFI | 0.17 | 0.115 | [−0.060, 0.401] | 1.479 | |||

| Others | 0.1 | 0.171 | [−0.243, 0.442] | 0.583 | |||

| Extraversion | Personality Measurement | QE(70) = 1530.131 *** | F(1, 67) = 0.749 *** | ||||

| NEO | 0.352 | [0.252, 0.452] | 7.014 | ||||

| IPIP | 0.263 | [0.118 ,0.407] | 3.633 | ||||

| TIPI | 0.282 | [0.072, 0.492] | 2.68 | ||||

| BFI | 0.435 | [0.279, 0.591] | 5.571 | ||||

| Others | 0.353 | [0.164, 0.541] | 3.725 | ||||

| Openness | Personality Measurement | QE(95) = 1715.517 *** | F(4, 95) = 2.712 *** | ||||

| NEO | 0.410 | 0.043 | [0.325, 0.496] | 9.532 | |||

| IPIP | 0.287 | 0.056 | [0.176, 0.398] | 5.142 | |||

| TIPI | 0.463 | 0.074 | [0.316, 0.610] | 6.253 | |||

| BFI | 0.548 | 0.065 | [0.419, 0.678] | 8.417 | |||

| Others | 0.307 | 0.104 | [0.101, 0.512] | 2.961 | |||

| Conscientiousness | Personality Measurement | QE(60) = 1025.024 *** | F(4, 77) = 0.547 ** | ||||

| NEO | 0.344 | [0.235, 0.454] | 6.256 | ||||

| IPIP | 0.257 | [0.124, 0.389] | 3.872 | ||||

| TIPI | 0.223 | [−0.017, 0.464] | 1.85 | ||||

| BFI | 0.270 | [0.100, 0.439] | 3.171 | ||||

| Others | 0.197 | [−0.040, 0.434] | 1.656 | ||||

| Neuroticism | Personality Measurement | QE(67) = 1398.499 *** | F(4, 2) = 0.692 | ||||

| NEO | −0.028 | 0.062 | [−0.153, 0.097] | −0.449 | |||

| IPIP | −0.09 | 0.083 | [−0.255, 0.076] | −1.08 | |||

| TIPI | −0.037 | 0.131 | [−0.287, 0.244] | −0.28 | |||

| BFI | −0.221 * | 0.103 | [−0.426, −0.015] | −2.145 | |||

| Others | −0.04 | 0.129 | [−0.297, 0.218] | −0.307 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhu, H.; Jia, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, R. The Relationship Between the Big Five Personality Model and Innovation Behavior: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091143

Zhu H, Jia F, Zhang Y, Wang R. The Relationship Between the Big Five Personality Model and Innovation Behavior: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091143

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Haidong, Feihang Jia, Yingxi Zhang, and Rui Wang. 2025. "The Relationship Between the Big Five Personality Model and Innovation Behavior: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 9: 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091143

APA StyleZhu, H., Jia, F., Zhang, Y., & Wang, R. (2025). The Relationship Between the Big Five Personality Model and Innovation Behavior: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(9), 1143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15091143