The Relationship of Family Cohesion and Teacher Emotional Support with Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: The Chain-Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Family Cohesion and Teacher Emotional Support in Relation to Prosocial Behavior

1.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion

1.3. The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life

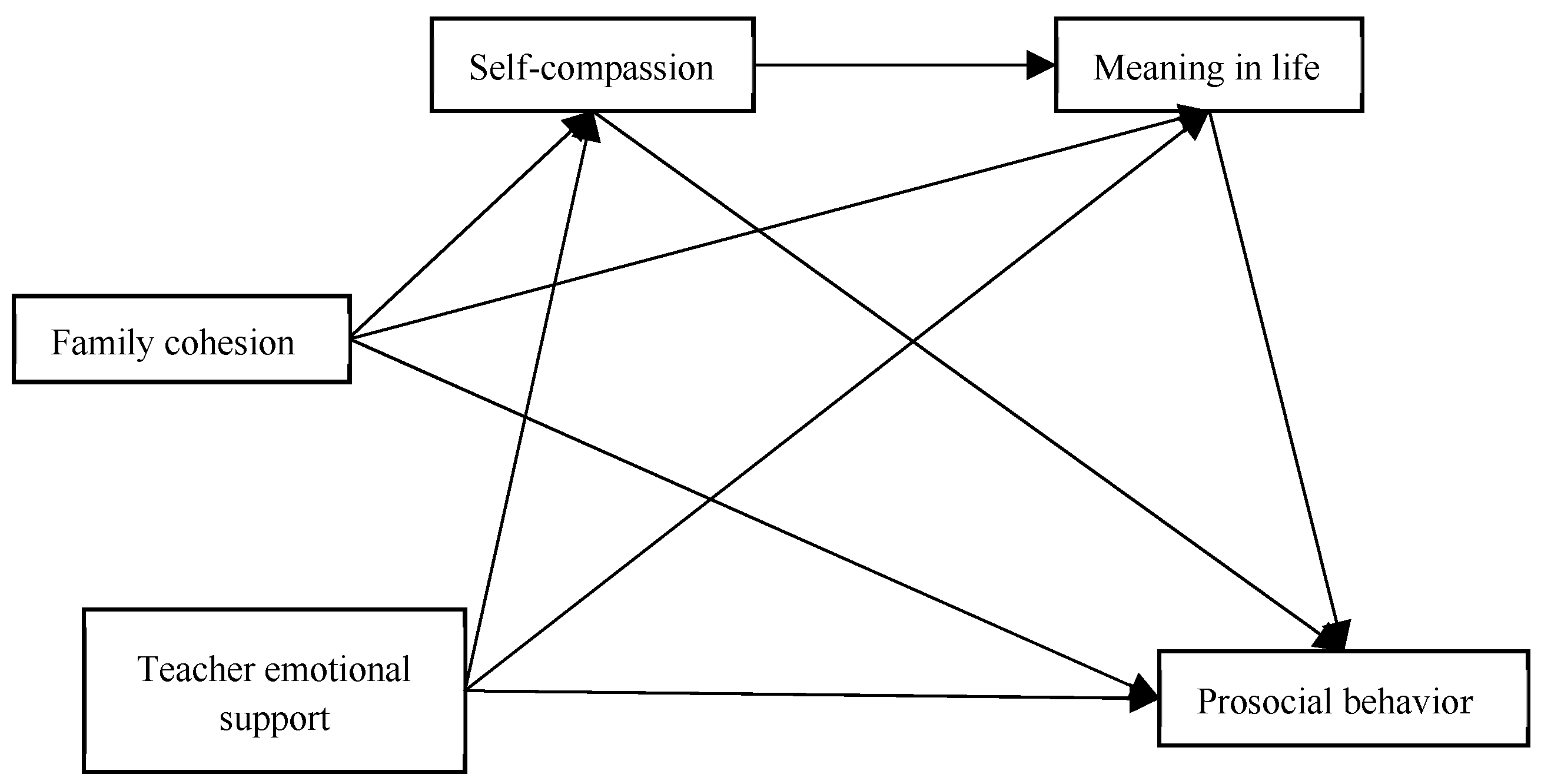

1.4. The Chain-Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Prosocial Behavior

2.2.2. Family Cohesion

2.2.3. Teacher Emotional Support

2.2.4. Self-Compassion

2.2.5. Meaning in Life

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias Test

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

3.3. Chain-Mediation Analysis for Total Prosocial Behavior Score

3.4. Chain-Mediation Analyses for Prosocial Behavior Subdimensions

4. Discussion

4.1. Family Cohesion and Teacher Emotional Support Predict Adolescent Prosocial Behavior

4.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Compassion

4.3. The Mediating Role of Meaning in Life

4.4. The Chain-Mediated Effect of Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life

4.5. Practical Significance and Implications for Adolescent Development

4.6. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, K. A., Slaten, C. D., Arslan, G., Roffey, S., Craig, H., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2021). School belonging: The importance of student and teacher relationships. In The palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 525–550). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, G., & Yıldırım, M. (2021). Perceived risk, positive youth-parent relationships, and internalizing problems in adolescents: Initial development of the meaningful school questionnaire. Child Indicators Research, 14(5), 1911–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (pp. 759–825). John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, L., Atkins, T., Perera, W., & Waller, M. (2024). Trajectories of parental warmth and the role they play in explaining adolescent prosocial behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(3), 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlo, G., & Randall, B. A. (2002). The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31(1), 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, B. R., Huang, J. X., Lin, P. T., & Fang, J. D. (2024). Love yourself, love others more: The “Altruistic” mechanism of self-compassion. Psychological Development and Education, 40(3), 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Li, X., Huebner, E. S., & Tian, L. (2022). Parent-child cohesion, loneliness, and prosocial behavior: Longitudinal relations in children. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 39(9), 2939–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datu, J. A. D. (2016). The synergistic interplay between positive emotions and maximization enhances meaning in life: A study in a collectivist context. Current Psychology, 35(3), 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, F. M., & Lamberti, D. M. (1986). Does social approval increase helping? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(2), 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N. (2020). Considering the role of positive emotion in the early emergence of prosocial behavior: Commentary on Hammond and Drummond. Developmental Psychology, 56(4), 843–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endedijk, H. M., Breeman, L. D., van Lissa, C. J., Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., den Boer, L., & Mainhard, T. (2022). The teacher’s invisible hand: A meta-analysis of the relevance of teacher-student relationship quality for peer relationships and the contribution of student behavior. Review of Educational Research, 92(3), 370–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, L. P., Shen, Q. J., Zheng, Y. P., Zhao, J. P., Jiang, S. A., Wang, L. W., & Wang, X. D. (1991). Preliminary evaluation of the Family Cohesion and Adaptability Scale (FACES) and Family Environment Scale (FES)—Comparative study of normal families and families of schizophrenic patients. Chinese Mental Health Journal, (5), 198–202, 238. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=0xftKHkdwWS1lXs1CHnmFrc_BK7mYf619R0iW9UgC5eDkNsja13t3czJzrk_XIFeGcKPAe5hzfUkWvSSi3fxhfFQURXob2aLVplogXEbm766GN_TopEVFkXcsio-9k5fkF-cPNs3_zUhGzbUUO-T4IDUI5zTERT1q1Hg7OChSjSQO6Yi3iZsVA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 28 October 1991).

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D. D., Li, X. Y., & Qiao, H. X. (2017). Development of the middle school student perceived teachers’ emotional support questionnaire. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 25(1), 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H. L., Jia, H. L., Guo, T. M., & Zou, L. L. (2014). The revision of self-compassion scale and its reliability and validity in adolescents. Psychological Research, 7(1), 36–40, 79. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=TD_mLQSGK6vDjwRSb6_e29ah3SQyI4LbmilqBq62EgVVpBIZiPs-JNnQ9W5f-84r311vs8wzSEv1Ta8GL94hlWcz6m9wtLqs_MghubXWL_80ZQozAFfsnWKwgKbWQLzH43JSoVgmVZDoO1Tq1B4kxeMEIBH2j5oodo0z5-C5bIR6emtF3pMPDCC10be1qEK1&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 1 February 2013).

- Hardy, S. A., & Carlo, G. (2005). Religiosity and prosocial behaviours in adolescence: The mediating role of prosocial values. Journal of Moral Education, 34(2), 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintsanen, M., Gluschkoff, K., Dobewall, H., Cloninger, C. R., Keltner, D., Saarinen, A., Wesolowska, K., Volanen, S.-M., Raitakari, O. T., & Pulkki-Råback, L. (2019). Parent-child-relationship quality predicts offspring dispositional compassion in adulthood: A prospective follow-up study over three decades. Developmental Psychology, 55(1), 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inwood, E., & Ferrari, M. (2018). Mechanisms of change in the relationship between self-compassion, emotion regulation, and mental health: A systematic review. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 10(2), 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isanejad, A. A., Saffarian Toosi, M. R., & Nejat, H. (2023). Comparing the effectiveness of self-compassion training and quality of life training on conditional self-worth, meaning of life, and emotional impulsivity among adolescents with coronavirus grief in Mashhad city. Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies, 4(9), 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N. (2017). Prosocial behavior increases perceptions of meaning in life. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(4), 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingle, K. E., & Van Vliet, K. J. (2019). Self-compassion from the adolescent perspective: A qualitative study. Journal of Adolescent Research, 34(3), 323–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kou, Y., Hong, H. F., Tan, C., & Li, L. (2007). Revisioning prosocial tendencies measure for adolescent. Psychological Development and Education, 23(1), 112–117. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=TD_mLQSGK6v5L6AAtoECpV7gmyFkByLCOHGpI5oBAQL-dIB6RDO9r7ZqPhGriqh56zBcID9b77EBc64QcKtjzi8sC6YKdXlvkZ80ujB7fqbaQeJMdNBp0DVGZk8oXd1W8UHO9BbMC_Cu7Nq3oH-ZjmD9AO7fNDPCeRcpeRo-_nOV0iDNErSUMxScR4x98VXmp_wPzOP887M=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 15 January 2007).

- Lee, C. T., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Memmott-Elison, M. K. (2017). The role of parents and peers on adolescents’ prosocial behavior and substance use. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 34(7), 1053–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., & Lerner, J. V. (2005). Positive youth development: A view of the issues. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Ye, B. J., Ni, L. Y., & Yang, Q. (2020). Family cohesion on prosocial behavior in college students: Moderated mediating effect. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(1), 178–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A., Wang, W., & Wu, X. (2021). Self-compassion and posttraumatic growth mediate the relations between social support, prosocial behavior, and antisocial behavior among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1864949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longobardi, C., Prino, L. E., Marengo, D., & Settanni, M. (2016). Student-teacher relationships as a protective factor for school adjustment during the transition from middle to high school. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maiya, S., Carlo, G., Gülseven, Z., & Crockett, L. (2020). Direct and indirect effects of parental involvement, deviant peer affiliation, and school connectedness on prosocial behaviors in U.S. Latino/a youth. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(10–11), 2898–2917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S. L., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P. D., & Sahdra, B. K. (2020). Is self-compassion selfish? The development of self-compassion, empathy, and prosocial behavior in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(S2), 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdams, D. P., & Olson, B. D. (2010). Personality development: Continuity and change over the life course. Annual Review of Psychology, 61(1), 517–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, K. D. (2023). Self-compassion: Theory, method, research, and intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 74(1), 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Dea, M. K., Igou, E. R., van Tilburg, W. A. P., & Kinsella, E. L. (2022). Self-compassion predicts less boredom: The role of meaning in life. Personality and Individual Differences, 186, 111360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D. H., Portner, J., & Bell, R. Q. (1982). FACES II: Family adaptability and cohesion evaluation scales. University of Minnesota, Department of Family Social Science. [Google Scholar]

- Pakarinen, E., Lerkkanen, M.-K., & von Suchodoletz, A. (2020). Teacher emotional support in relation to social competence in preschool classrooms. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 43(4), 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, S., Choi, M., Miller, M., Halgunseth, L. C., van Schaik, S. D., & Brenick, A. (2021). Family cohesion and school belongingness: Protective factors for immigrant youth against bias–based bullying. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2021(177), 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sijtsema, J. J., Nederhof, E., Veenstra, R., Ormel, J., Oldehinkel, A. J., & Ellis, B. J. (2013). Effects of family cohesion and heart rate reactivity on aggressive/rule-breaking behavior and prosocial behavior in adolescence: The tracking adolescents’ individual lives survey study. Development and Psychopathology, 25(3), 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, H., & Chong, S. S. (2022). What predicts meaning in life? The role of perfectionistic personality and self-compassion. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 35(2), 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R., Ren, Y., Li, X., Jiang, Y., Liu, S., & You, J. (2020). Self-compassion and family cohesion moderate the association between suicide ideation and suicide attempts in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 79(1), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, M. A. Q., Vo-Thanh, T., Soliman, M., Khoury, B., & Chau, N. N. T. (2022). Self-compassion, mindfulness, stress, and self-esteem among vietnamese university students: Psychological well-being and positive emotion as mediators. Mindfulness, 13(10), 2574–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verity, L., Yang, K., Nowland, R., Shankar, A., Turnbull, M., & Qualter, P. (2024). Loneliness from the adolescent perspective: A qualitative analysis of conversations about loneliness between adolescents and childline counselors. Journal of Adolescent Research, 39(5), 1413–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Y., Ding, W., Song, X. C., Sun, Z. X., Xie, R. B., & Li, W. J. (2023). The effect of peer and teacher-student relationship on academic burnout of vocational high school students: The Chain mediating roles of perceived discrimination and self-compassion. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 21(5), 691–697. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=TD_mLQSGK6uFMJV9iTU7YWjz0QlS4B4D-uIeK7X3Ntl7qhk3NtumnIixKOPd_CP5qyKSB2_lOQwv-X_8IYqMc-wvykhOn8Nwej9HKHlIjrrqMIDaP7Db_FowFN6o1Sbh9vLXK2Qf_PPIWN11o8ssFlPmtgOWIqZNJMNPbltPiPABLJB0xoSO7OkHmom3-T5Qk7bSyCY8bMY=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- Wang, W. C., Wu, X. C., Tian, Y. X., & Zhou, X. (2018). Mediating roles of meaning in life in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder, posttraumatic growth and prosocial behavior among adolescents after the Wenchuan earthquake. Psychological Development and Education, 34(1), 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Q. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the meaning in life questionnaire in Chinese middle school students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21(5), 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(2), 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R., Filisetti, L., & Looney, L. (2007). Adolescent prosocial behavior: The role of self-processes and contextual cues. Child Development, 78(3), 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M. Z., Li, Y., Yin, J. R., Li, X. M., & Sun, X. L. (2023). Relationship between family rituals and prosocial tendency of adolescents: The Mediating role of meaning in life. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(1), 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Wen, Z., Shen, J., Tan, Y., Liu, X., Yang, Y., & Zheng, X. (2023). Longitudinal relationship between prosocial behavior and meaning in life of junior high school students: A three-wave cross-lagged study. Journal of Adolescence, 95(5), 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, H. X., Zhang, J., Ye, B. J., Zheng, X., & Sun, P. Z. (2012). Common method variance effects and the models of statistical approaches for controlling it. Advances in Psychological Science, 20(5), 757–769. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=TD_mLQSGK6uXx0jPkUinZk_j85yjY9YbDzVV8S3Lq_GgyAipDA4jUQfXx-sPWyIbFku8yX4of6kFcEX7zzBFQKdsDsgy8KgBSMiDRlTP8lqhjNPm_9Mjx5L4fefhTZ6ytvpzboSQ7CWr-BqT6LXpKbN767allPN8NoAPXQZZDhahKh4VY7k7XcXCrS_9LQJ6RZ1yeiK7XCE=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 25 June 2012). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z., Zhang, D., Ding, H., Zheng, X., Lee, R. C.-M., Yang, Z., Mo, P. K.-H., Lee, E. K.-P., & Wong, S. Y.-S. (2022). Association of positive and adverse childhood experiences with risky behaviours and mental health indicators among Chinese university students in Hong Kong: An exploratory study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1), 2065429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X., Ma, H., Zhang, L., Xue, J., & Hu, P. (2023). Perceived social support, depressive symptoms, self-compassion, and mobile phone addiction: A moderated mediation analysis. Behavioral Sciences, 13(9), 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Z., & Enright, R. (2023). Social class and prosocial behavior in early adolescence: The moderating roles of family and school factors. Journal of Moral Education, 52(3), 310–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yela, J. R., Crego, A., Gómez-Martínez, M. Á., & Jiménez, L. (2020). Self-compassion, meaning in life, and experiential avoidance explain the relationship between meditation and positive mental health outcomes. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(9), 1631–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L. J., Jiang, L. J., & Peng, Y. (2022). The influence of family environment and teacher support on middle school students’ academic procrastination: The Chain mediating effect of satisfaction of basic psychological needs and psychological capital. Studies of Psychology and Behavior, 20(4), 501–507. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=TD_mLQSGK6vE2DI5n9jjM1LXE3EOjwqQWjbsmbOsklgTPMsWHtUpKbR0azzYI1Xc2SVyJykJIYbCQbIAvUvgQg_7kUcIV2OefpCO3cjaIf-HH3n3gZdBcaMtywP40bpv9G5bzVnL83myQFumAIsNwV3NuXg9WN8jBxvG7UJLM2wvPfpI9HCY0d0xB-Bq9-9fIXaARrtDvNg=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Zheng, K., Johnson, S., Jarvis, R., Victor, C., Barreto, M., Qualter, P., & Pitman, A. (2023). The experience of loneliness among international students participating in the BBC Loneliness Experiment: Thematic analysis of qualitative survey data. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 4, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipagan, F. B., & Galvez Tan, L. J. T. (2023). From self-compassion to life satisfaction: Examining the mediating effects of self-acceptance and meaning in life. Mindfulness, 14(9), 2145–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Prosocial behavior | 93.73 ± 17.38 | ||||

| 2. Family cohesion | 56.89 ± 12.60 | 0.37 | |||

| 3. Teacher emotional support | 66.53 ± 14.19 | 0.47 | 0.43 | ||

| 4. Self-compassion | 40.28 ± 8.63 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.44 | |

| 5. Meaning in life | 48.37 ± 10.79 | 0.36 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.46 |

| Independent Variable | Paths | Effect | SE | 95% CI | Percentage of Total Effect (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| X1 | Total effect 1 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.24 | |

| c1: Direct (X1 → Y) | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.20 | 74.11 | |

| ind1: X1 → M1 → Y | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 0.04 | 10.15 | |

| ind2: X1 → M2 → Y | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 10.66 | |

| ind3: X1 → M1 → M2 → Y | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 4.57 | |

| X2 | Total effect 2 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.34 | 0.44 | |

| c2: Direct (X2 → Y) | 0.34 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 87.76 | |

| ind4: X2 → M1 → Y | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.04 | 4.59 | |

| ind5: X2 → M2 → Y | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 5.61 | |

| ind6: X2 → M1 → M2→ Y | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.01 | 2.04 | |

| Path Comparison | c1–c2 | −0.20 | 0.05 | 0.11 | 0.28 | |

| ind3–ind6 | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.004 | 0.001 | ||

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Indirect Effect (X → M1 → M2 → Y) | χ2(df) | p | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA [90% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | 95% CI | Percentage of Total Effect (%) | ||||||||

| Total Score | X1 X2 | 0.009 0.008 | 0.005–0.015 0.004–0.013 | 4.57 2.04 | 67.874 | <0.001 | 0.953 | 0.930 | 0.039 | 0.064 [0.050, 0.079] |

| Public | X1 X2 | 0.011 0.009 | 0.006–0.017 0.005–0.015 | 10 2.63 | 67.887 | <0.001 | 0.946 | 0.919 | 0.039 | 0.064 [0.050, 0.079] |

| Anonymous | X1 X2 | 0.006 0.005 | 0.001–0.011 0.001–0.010 | 3.66 1.60 | 67.887 | <0.001 | 0.947 | 0.921 | 0.039 | 0.064 [0.050, 0.079] |

| Altruistic | X1 X2 | 0.004 0.004 | −0.001–0.010 −0.001–0.009 | 2.02 1.29 | 67.887 | <0.001 | 0.949 | 0.923 | 0.039 | 0.064 [0.050, 0.079] |

| Compliant | X1 X2 | 0.006 0.005 | 0.001–0.011 0.001–0.010 | 3.66 1.55 | 67.887 | <0.001 | 0.947 | 0.921 | 0.039 | 0.064 [0.050, 0.079] |

| Emotional | X1 X2 | 0.010 0.009 | 0.005–0.016 0.005–0.014 | 7.41 2.68 | 67.887 | <0.001 | 0.947 | 0.920 | 0.039 | 0.064 [0.050, 0.079] |

| Dire | X1 X2 | 0.009 0.008 | 0.004–0.016 0.003–0.014 | 5.03 3.07 | 67.887 | <0.001 | 0.945 | 0.917 | 0.039 | 0.064 [0.050, 0.079] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, P.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, J.; Fu, S.; Bai, X.; Feng, W. The Relationship of Family Cohesion and Teacher Emotional Support with Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: The Chain-Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081126

Li P, Zhou X, Jiang J, Fu S, Bai X, Feng W. The Relationship of Family Cohesion and Teacher Emotional Support with Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: The Chain-Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081126

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Peng, Xia Zhou, Jiali Jiang, Shuying Fu, Xuejun Bai, and Wenbin Feng. 2025. "The Relationship of Family Cohesion and Teacher Emotional Support with Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: The Chain-Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081126

APA StyleLi, P., Zhou, X., Jiang, J., Fu, S., Bai, X., & Feng, W. (2025). The Relationship of Family Cohesion and Teacher Emotional Support with Adolescent Prosocial Behavior: The Chain-Mediating Role of Self-Compassion and Meaning in Life. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1126. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081126