Exploring Interaction Dynamics in Dog-Assisted Therapy: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Setting

2.2. Therapy Sessions

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

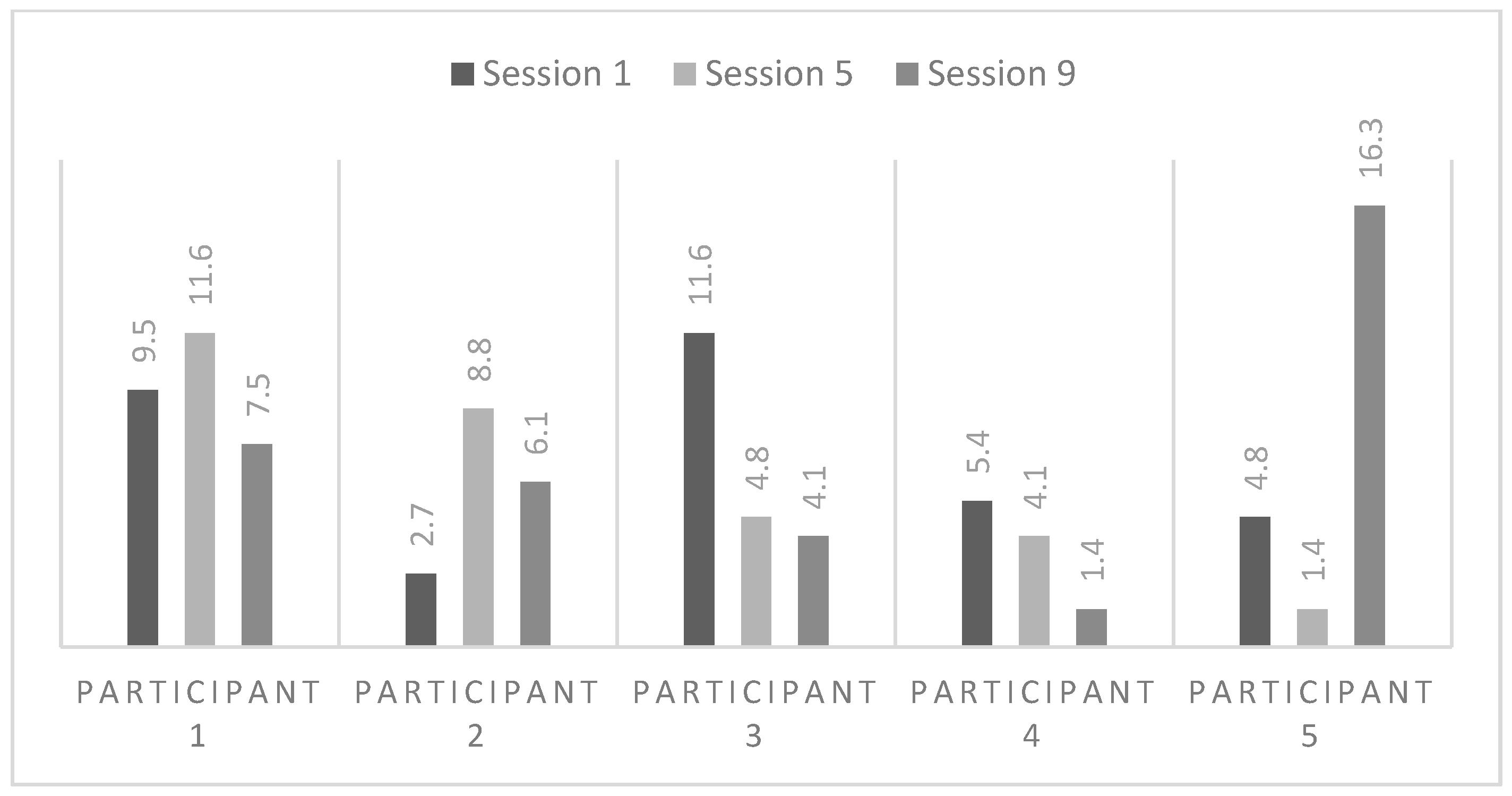

3.1. Frequencies of Active and Passive Participation During Therapy Sessions

3.2. Frequencies of Focus Direction During Therapy Sessions

3.3. Frequencies of Joint Focus During Therapy Sessions

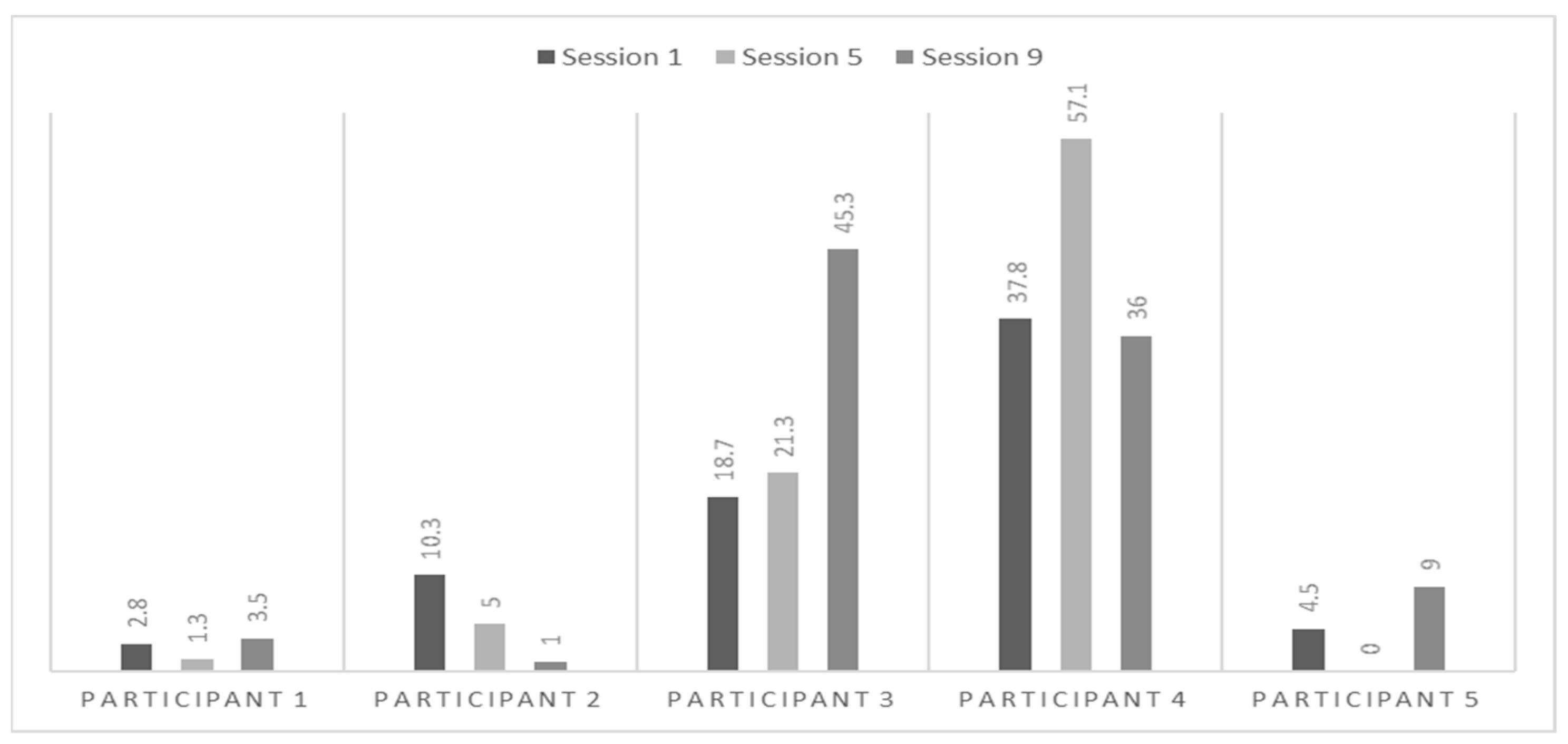

3.4. Frequencies of Physical Contact During DAT Sessions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASD | Autism Spectrum Disorder |

| BSI | Behavioural Science Institute, Radboud University |

| DAT | Dog Assisted Therapy |

| ECSW | Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences, Radboud University |

| IAHAIO | International Association of Human–Animal Interaction Organizations |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Ethogram

Operational Definitions

- Dog Behaviours:

- ➢

- Dog lying: The dog rests on the ground with its body wholly or partially in contact with the floor.

- ➢

- Dog sitting: The dog is seated with its hindquarters on the floor and front legs extended.

- ➢

- Dog standing: The dog is on all four legs without movement.

- ➢

- Dog walking: The dog moves forward or changes position using all four legs.

- ➢

- Attention client: The dog is visibly oriented towards the client, with its head or body directed towards them.

- ➢

- Attention therapist: The dog is visibly oriented towards the therapist, with its head or body directed towards it.

- ➢

- Attention other: The dog is visibly oriented towards another individual or object in the environment.

- ➢

- Dog makes physical contact: The dog initiates direct physical contact with the client, therapist, or another individual (e.g., nudging, leaning, pawing).

- ➢

- Other: Any behaviour the client displays that does not fit the above categories.

- Client Behaviours:

- ➢

- Client sitting: The client is seated on a chair, bench, or the floor.

- ➢

- Client standing: The client is upright and stationary.

- ➢

- Client walking: The client is moving from one location to another.

- ➢

- Attention dog: The client is visibly oriented towards the dog, with eye contact or body direction.

- ➢

- Attention therapist: The client is visibly oriented towards the therapist, with eye contact or body direction.

- ➢

- Attention other: The client is oriented towards another individual or object in the environment.

- ➢

- Petting dog: The client physically touches or stroking the dog with their hands.

- ➢

- Other: Any behaviour the client displays that does not fit the above categories.

- Therapist Behaviours:

- ➢

- Therapist sitting: The therapist is seated on a chair, bench, or the floor.

- ➢

- Therapist standing: The therapist is upright and stationary.

- ➢

- Therapist walking: The therapist is moving from one location to another.

- ➢

- Attention dog: The therapist is visibly oriented towards the dog, with eye contact or body direction.

- ➢

- Attention client: The therapist is visibly oriented towards the client, with eye contact or body direction.

- ➢

- Attention other: The therapist is oriented towards another individual or object in the environment.

- ➢

- Petting dog: The therapist physically touches or stroking the dog with their hands.

- ➢

- Other: Any behaviour the therapist displays that does not fit into the above categories.

References

- Abadi, M. R. H., Hase, B., Dell, C., Johnston, J. D., & Kontulainen, S. (2022). Dog-assisted physical activity intervention in children with autism spectrum disorder: A feasibility and efficacy exploratory study. Anthrozoös, 35(4), 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beetz, A., Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Julius, H., & Kotrschal, K. (2012). Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergland, A., Olsen, C. F., & Ekerholt, K. (2018). The effect of psychomotor physical therapy on health-related quality of life, pain, coping, self-esteem, and social support. Physiotherapy Research International, 23(4), e1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binfet, J., Green, F. L. L., & Draper, Z. A. (2021). The importance of client–canine contact in canine-assisted interventions: A randomised controlled trial. Anthrozoös, 35(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, A. B., Annese, C. D., Empoliti, J. H., & Flanagan, J. M. (2020). The experience of animal assisted therapy on patients in an acute care setting. Clinical Nursing Research, 30(4), 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, M., Filugelli, L., Mair, A., Normando, S., Mutinelli, F., & Contalbrigo, L. (2024). How to measure human-dog interaction in dog-assisted interventions? A scoping review. Animals, 14(3), 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A. (2018). The use of the relationship with animals vicariously—Role modelling. In Animal assisted therapy (4th ed., p. 146). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Glenk, L. M., & Foltin, S. (2021). Therapy dog welfare revisited: A review of the literature. Veterinary Sciences, 8(10), 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajfoner, D., Harte, E., Potter, L., & McGuigan, N. (2017). The effect of dog-assisted intervention on student well-being, mood, and anxiety. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(5), 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grové, C., Henderson, L., Lee, F., & Wardlaw, P. (2021). Therapy dogs in educational settings: Guidelines and recommendations for implementation. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8, 655104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, E. G., Rodríguez, L. S., Santamarina-Perez, P., Barros, L. H., Giralt, M. G., Elizalde, E. D., Ubach, F. R., Gonzalez, M. R., Yuste, Y. P., Téllez, C. D., Cela, S. R., Gisbert, L. R., Medina, M. S., Ballesteros-Urpi, A., & Liñan, A. M. (2022). The benefits of dog-assisted therapy as complementary treatment in a children’s mental health day hospital. Animals, 12(20), 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrop, A., & Daniels, M. (1986). Methods of time sampling: A reappraisal of momentary time sampling and partial interval recording. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis, 19(1), 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hüsgen, C. J., Peters-Scheffer, N. C., & Didden, R. (2022). A systematic review of dog-assisted therapy in children with behavioural and developmental disorders. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 6(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAHAIO. (2018). White paper on animal-assisted interventions. IAHAIO. Available online: https://iahaio.org/best-practice/white-paper-on-animal-assisted-interventions/ (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- ISAAT. (2024). STANDARDS. Available online: https://isaat.org/standards/ (accessed on 7 April 2025).

- Jones, M. G., Rice, S. M., & Cotton, S. M. (2019). Incorporating animal-assisted therapy in mental health treatments for adolescents: A systematic review of canine-assisted psychotherapy. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavín-Pérez, A. M., Martín-Sánchez, C., Martínez-Núñez, B., Lobato-Rincón, L. L., Villafaina, S., González-García, I., Mata-Cantero, A., Graell, M., Merellano-Navarro, E., & Collado-Mateo, D. (2021). Effects of dog-assisted therapy in adolescents with eating disorders: A study protocol for a pilot controlled Trial. Animals, 11(10), 2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meixner, J., & Kotrschal, K. (2022). Animal-assisted interventions with dogs in special education—A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 876290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignot, A., De Luca, K., Servais, V., & Leboucher, G. (2022). Handlers’ representations on therapy dogs’ welfare. Animals, 12(5), 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, M., Mitsui, S., En, S., Ohtani, N., Ohta, M., Sakuma, Y., Onaka, T., Mogi, K., & Kikusui, T. (2015). Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds. Science, 348(6232), 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramachandran, V. S. (2012). Encyclopedia of human behavior. Elsevier eBooks. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramseyer, F., & Tschacher, W. (2011). Nonverbal synchrony in psychotherapy: Coordinated body movement reflects relationship quality and outcome. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roma, R. P. S., Tardif-Williams, C. Y., Moore, S. A., & Bosacki, S. L. (2021). A transdisciplinary perspective on dog-handler-participant interactions in animal assisted activities for children, youth and young adults. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin, 9, 62–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, H., Paterson, M. B. A., Georgiou, F., Pachana, N. A., & Phillips, C. J. C. (2020). Who is pulling the leash? Effects of human gender and dog sex on human–dog dyads when walking on-leash. Animals, 10(10), 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udvarhelyi-Tóth, K. M., Iotchev, I. B., Kubinyi, E., & Turcsán, B. (2024). Why do people choose a particular dog? A mixed-methods analysis of factors owners consider important when acquiring a dog, on a convenience sample of austrian pet dog owners. Animals, 14(18), 2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Schooten, A., Peters-Scheffer, N., Enders-Slegers, M., Verhagen, I., & Didden, R. (2024). Dog-assisted therapy in mental health care: A qualitative study on the experiences of patients with intellectual disabilities. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 14(3), 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voutilainen, L., & Peräkylä, A. (2016). Interactional practices of psychotherapy. In Palgrave macmillan UK eBooks (pp. 540–557). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C., Grob, C., & Hediger, K. (2022). Specific and non-specific factors of animal-assisted interventions considered in research: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 931347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlfarth, R., Mutschler, B., Beetz, A., Kreuser, F., & Korsten-Reck, U. (2013). Dogs motivate obese children for physical activity: Key elements of a motivational theory of animal-assisted interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A., & Wei, R. (2023). The benefits of dog-assisted therapy for children with anxiety. Psychotherapy and Counselling Journal of Australia, 11(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Focus Direction | Towards Participant | Towards Dog | Other | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Participant 1 | 51% | 65% | 44% | 21% | 12% | 37% | 28% | 24% | 20% |

| Participant 2 | 61% | 70% | 69% | 27% | 16% | 10% | 12% | 14% | 21% |

| Participant 3 | 41% | 64% | 51% | 43% | 24% | 36% | 16% | 12% | 13% |

| Participant 4 | 62% | 67% | 66% | 20% | 14% | 12% | 18% | 19% | 20% |

| Participant 5 | 47% | 57% | 54% | 38% | 34% | 42% | 15% | 9% | 5% |

| Average | 53% | 64% | 57% | 30% | 20% | 27% | 18% | 16% | 16% |

| Focus Direction | Towards Therapist | Towards Dog | Other | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Participant 1 | 13% | 13% | 24% | 36% | 20% | 48% | 51% | 67% | 28% |

| Participant 2 | 38% | 41% | 60% | 43% | 23% | 16% | 19% | 36% | 25% |

| Participant 3 | 47% | 63% | 28% | 40% | 33% | 49% | 13% | 4% | 23% |

| Participant 4 | 70% | 63% | 72% | 21% | 21% | 19% | 9% | 16% | 9% |

| Participant 5 | 50% | 55% | 42% | 42% | 33% | 31% | 8% | 12% | 27% |

| Average | 44% | 47% | 45% | 37% | 26% | 33% | 20% | 27% | 23% |

| Focus Direction | Towards Therapist | Towards Participant | Other | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Participant 1 | 11% | 16% | 5% | 24% | 17% | 5% | 65% | 67% | 91% |

| Participant 2 | 8% | 2% | 5% | 26% | 17% | 10% | 66% | 81% | 85% |

| Participant 3 | 21% | 13% | 8% | 16% | 43% | 50% | 63% | 44% | 42% |

| Participant 4 | 4% | 11% | 8% | 27% | 26% | 17% | 69% | 63% | 74% |

| Participant 5 | 15% | 8% | 3% | 33% | 37% | 36% | 52% | 55% | 61% |

| Average | 12% | 10% | 6% | 25% | 28% | 24% | 63% | 62% | 71% |

| Participant–Dog Dyad | Therapist–Dog Dyad | Participant–Therapist Dyad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Session | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| Participant 1 | 15% | 4% | 5% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 7% | 12% | 22% |

| Participant 2 | 21% | 14% | 6% | 0% | 1% | 2% | 32% | 37% | 55% |

| Participant 3 | 13% | 28% | 28% | 4% | 3% | 2% | 33% | 55% | 26% |

| Participant 4 | 14% | 12% | 12% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 56% | 61% | 64% |

| Participant 5 | 24% | 28% | 22% | 6% | 0% | 2% | 44% | 51% | 40% |

| Average | 18% | 17% | 15% | 3% | 2% | 2% | 34% | 43% | 41% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hüsgen, C.J.; Peters-Scheffer, N.; Didden, R. Exploring Interaction Dynamics in Dog-Assisted Therapy: An Observational Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081115

Hüsgen CJ, Peters-Scheffer N, Didden R. Exploring Interaction Dynamics in Dog-Assisted Therapy: An Observational Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081115

Chicago/Turabian StyleHüsgen, Candela Jasmin, Nienke Peters-Scheffer, and Robert Didden. 2025. "Exploring Interaction Dynamics in Dog-Assisted Therapy: An Observational Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081115

APA StyleHüsgen, C. J., Peters-Scheffer, N., & Didden, R. (2025). Exploring Interaction Dynamics in Dog-Assisted Therapy: An Observational Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1115. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081115