Reading Interest Profiles Among Preservice Chinese Language Teachers: Why They Begin to Like (or Dislike) Reading

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Reader Profiles

1.2. Reading Interest and Affecting Factors

1.3. Chinese Educational Context

1.4. The Present Study

- What underlying reading interest profiles can be identified among preservice Chinese language teachers?

- What factors made them begin to like or dislike reading?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

3.2. Reading Interest Profiles of Preservice Chinese Language Teachers

3.3. Why Did They Begin to Like Reading? The Motivators

3.4. Why Did They Begin to Dislike Reading? The Barriers

3.5. Profile-Specific Motivators and Barriers

4. Limitations and Educational Implications

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Educational Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Reading Interest Questionnaire

| Recall your reading experience from childhood to the present, and draw your reading interest curves in the figure below. Note: First, identify the period with the highest reading interest and circle its corresponding data dot. Use this point as a benchmark to record the reading interest levels for other periods. Finally, connect all plotted points chronologically to complete the reading interest curve. | |||||||||

high low | 10 | ||||||||

| 9 | |||||||||

| 8 | |||||||||

| 7 | |||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||

| 0 | |||||||||

| preschool | 1–2 grades | 3–4 grades | 5–6 grades | middle school | high school | college | |||

| Based on the graph, please indicate in which periods did you show the highest and lowest reading interest levels, and what were the possible reasons? In which period did your reading interest level show significant changes, and what factors contribute to this change? | |||||||||

| Period with the highest reading interest level and reason: | |||||||||

| Period with the lowest reading interest level and reason: | |||||||||

| Change point in reading interest and reason: | |||||||||

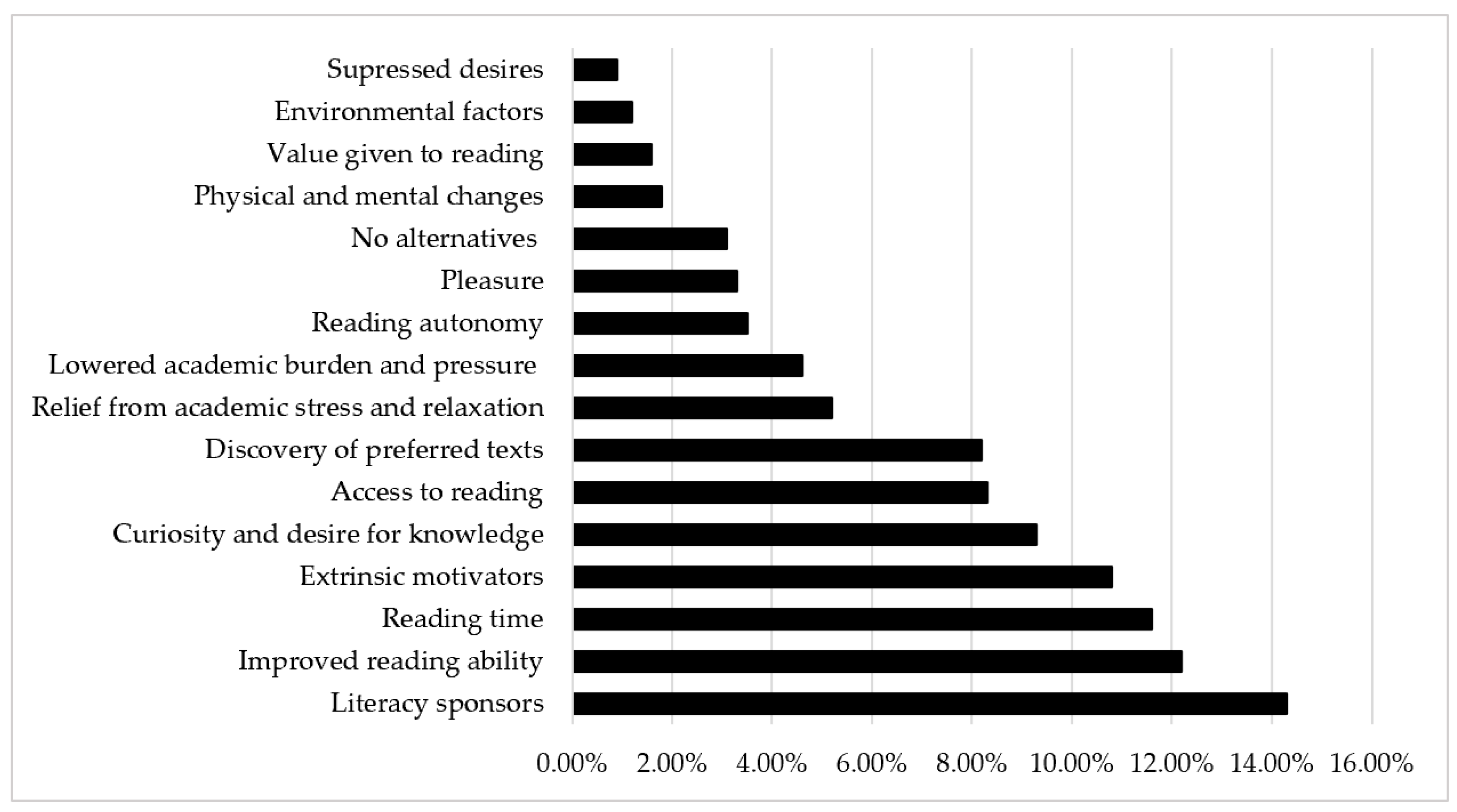

Appendix B. Why Preservice Chinese Language Teachers Begin to Like Reading: The Coding Examples

| Themes | Descriptions | Examples |

| Literacy sponsors (n = 177, 14.3%) | Statements indicating literacy support from various sponsors, including teachers (n = 74, 6.0%), peers (n = 58, 4.7%), family members (n = 37, 3.0%), and school (n = 8, 0.6%). |

|

| Improved reading ability (n = 152, 12.2%) | Statements referring to general improvement in reading ability (n = 59, 4.8%) and those related to word identification (n = 45, 3.6%), comprehension (n = 17, 1.4%), background knowledge (n = 15, 1.2%), cognitive development (n = 11, 0.9%), and empathy (n = 5, 0.4%). |

|

| Reading time (n = 144, 11.6%) | Sufficient time was guaranteed for reading. |

|

| Extrinsic motivators (n = 134, 10.8%) | Statements indicating external incentives, including those driven by major (n = 61, 4.9%), academic needs (n = 53, 4.3%), and self-development (n = 20, 1.6%). |

|

| Curiosity and desire for knowledge (n = 116, 9.3%) | The intrinsic need to learn topics that interested oneself or to learn about the world. |

|

| Access to reading (n = 103, 8.3%) | Statements referring to general access to reading (n = 65, 5.2%), access to more diverse books (n = 18, 1.5%), and access to reading through digital devices (n = 20, 1.6%) |

|

| Discovery of preferred texts (n = 102, 8.2%) | Statements referring to the text types or genres participants preferred, such as story books, fairy tales, (online) novels, adventure, fantasy, magazines, and historical books. |

|

| Relief from academic stress and relaxation (n = 65, 5.2%) | Reading was regarded as a way to relieve academic stress and achieve relaxation particularly in an extremely competitive and performance-oriented learning context. |

|

| Lowered academic burdens and pressure (n = 57, 4.6%) | Statements referring to a lowered academic burdens and pressure that enabled students to have the time and psychological leisure to read. |

|

| Pleasure (n = 41, 3.3%) | Statements referring to pleasure or enjoyment obtained from reading. Reading became an important form of entertainment especially under great academic pressure. |

|

| Reading autonomy (n = 43, 3.5%) | More freedom in reading, such as choosing books freely, reading independently, and no assignments after reading. |

|

| No alternatives (n = 39, 3.1%) | Statements indicating a lack of other forms of entertainment especially no digital devices available. |

|

| Physical and mental changes (n = 22, 1.8%) | Statements referring to physical and mental changes especially entering adolescence, such as emotional fluctuations, mental maturation, and identity seeking. |

|

| Value given to reading (n = 20, 1.6%) | Statements indicating the recognition of the value and power of reading. |

|

| Environmental factors (n = 15, 1.2%) | Statements referring to external environmental factors, such as changes in learning environment and reading atmosphere. |

|

| Suppressed desires (n = 11, 0.9%) | Suppressed desires to read due to a busy academic schedule and high academic pressure were suddenly released. |

|

Appendix C. Why Preservice Chinese Language Teachers Begin to Dislike Reading: The Coding Examples

| Themes | Descriptions | Examples |

| Academic burdens and pressure (n = 270, 29.8%) | Statements that refer to academic burdens (n = 98, 10.8%), academic pressure (n = 90, 9.9%), no time (n = 51, 5.6%), reading for examinations (n = 19, 2.1%), and reading for academic achievement (n = 12, 1.3%). |

|

| Availability of alternatives (n = 195, 21.5%) | Availability of other activities for entertainment, including free play, watching TV, and most importantly, using digital devices (n = 78, 8.6%). |

|

| Lack of reading ability (n = 190, 20.9%) | Statements indicating lack of ability to recognize words (n = 79, 8.7%), comprehend texts (n = 56, 6.1%), concentration (n = 15, 1.7%), lack of reading awareness (n = 29, 3.2%), and lack of background knowledge (n = 11, 1.2%). |

|

| Loss of reading autonomy (n = 90, 9.9%) | Statements that refer to loss of freedom in reading, including required readings (n = 33, 3.6%), reading accountability (n = 28, 3.1%), limitations in extracurricular reading materials (n = 16, 1.8%), teaching approach (n = 7, 0.8%), and lack of self-selection (n = 6, 0.7%). |

|

| Lack of literacy sponsors (n = 40, 4.4%) | Statements that refer to a lack of literacy support from various sponsors, especially parents and teachers. |

|

| Limited access to reading (n = 38, 4.2%) | Statements that refer to a lack of access to reading resources, such as having no bookstore or library nearby and lacking reading materials at home. |

|

| Inappropriate texts (n = 37, 4.1%) | Texts that do not match readers’ interests or have an excessively high difficulty level. |

|

| Environmental factors (n = 17, 1.9%) | Statements that refer to external environmental factors, such as changes in learning environment and reading atmosphere. |

|

| Utilitarian mindset (n = 15, 1.7%) | Reading is regarded as a means of achieving academic success or professional advancement. |

|

| Mood (n = 8, 0.9%) | Statements indicating the lack of mental conditions to read. |

|

| Lack of recognition of reading value (n = 7, 0.8%) | Statements indicating a lack of awareness or recognition of the value and power of reading. |

|

References

- Alexander, J. E., & Filler, R. C. (1976). Attitudes and reading. International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, P. A. (1997). Knowledge-seeking and self-schema: A case for the motivational dimensions of exposition. Educational Psychologist, 32(2), 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, E. M., & Midgley, C. (1997). Changes in achievement goal orientations, perceived academic competence, and grades across the transition to middle-level schools. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22(3), 269298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R. C. (1996). Research foundations to support wide reading. In V. Greaney (Ed.), Promoting reading in developing countries (pp. 55–77). International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Applegate, A. J., & Applegate, M. D. (2004). The Peter Effect: Reading habits and attitudes of preservice teachers. The Reading Teacher, 57(6), 554–563. [Google Scholar]

- Applegate, A. J., Applegate, M. D., Mercantini, M. A., McGeehan, C. M., Cobb, J. B., DeBoy, J. R., Modla, V. B., & Lewinski, K. E. (2014). The Peter Effect revisited: Reading habits and attitudes of college students. Literacy Research and Instruction, 53(3), 188–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenbeck, G. (1986). Aliteracy: The relationship between the electronic culture and voluntary reading [UNF Graduate theses and dissertations, UNF]; p. 56. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/56 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Bus, A. G., Neuman, S. B., & Roskos, K. (2020). Screens, apps, and digital books for young children: The promise of multimedia. AERA Open, 6(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, J. W., & Tunmer, W. E. (1995). Development of young children’s reading self-concepts: An examination of emerging subcomponents and their relationship with reading achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(1), 154–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S. L. (2016). Re-thinking aliteracy: When undergraduates surrender their reading choices. Literacy, 50(1), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C. (2019). Children and young people’s reading in 2017/18: Findings from our Annual Literacy Survey. National Literacy Trust. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C., & Rumbold, K. (2006). Reading for pleasure: A research overview. National Literacy Trust. Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED496343.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2024).

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis. With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, E. H., & Castle, M. (1994). Fostering the love of reading: The affective domain in reading education. International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- de Bondt, M., Willenberg, I. A., & Bus, A. G. (2020). Do book giveaway programs promote the home literacy environment and children’s literacy-related behavior and skills? Review of Educational Research, 90(3), 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doiron, R. (1994). Using nonfiction in a read-aloud program: Letting the facts speak for themselves. The Reading Teacher, 47(8), 616–624. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., & Midgley, C. (1989). Stage/environment fit: Developmentally appropriate classrooms for early adolescents. In R. E. Ames, & C. Ames (Eds.), Research on motivation in education (Vol. 3, pp. 139–186). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Enders, C. K. (2005). Maximum likelihood estimation. In B. S. Everitt, & D. C. Howell (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. Wiley. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambrell, L. B., Malloy, J. A., & Mazzoni, S. A. (2011). Evidence-based best practices in comprehensive literacy instruction. In L. M. Morrow, & L. B. Gambrell (Eds.), Best practices in literacy instruction (4th ed., pp. 11–36). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J. T., & Davis, M. H. (2003). Motivating struggling readers in middle school through an engagement model of classroom practice. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(1), 59–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. T., Hoa, L. W., Wigfield, A., Tonks, S. M., & Perencevich, K. C. (2006). From spark to fire: Can situational reading interest lead to long-term reading motivation? Reading Research and Instruction, 45(2), 91–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J. T., & Klauda, S. L. (2015). Engagement and motivational processes in reading. In P. Afflerbach (Ed.), Handbook of individual differences in reading: Reader, text, and context (pp. 41–53). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3, pp. 403–420). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., & You, W. (2012). Instructional contexts for engagement and achievement in reading. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 601–634). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakemulder, F., & Mangen, A. (2024). Literary reading on paper and screens: Associations between reading habits and preferences and experiencing meaningfulness. Reading Research Quarterly, 59(1), 57–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heins, E. L. (1984). A challenge to young-and old-adults. Horn Book Magazine, 50(4), 426–427. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, D. Y. F. (1986). Chinese patterns of socialization: A critical review. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The psychology of the Chinese people (pp. 1–37). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S., Orellana, P., & Capps, M. (2016). U.S. and Chilean college students’ reading practices: A cross-cultural perspective. Reading Research Quarterly, 51(4), 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, B. G., Conradi, K., McKenna, M. C., & Jones, J. S. (2015). Motivation: Approaching an elusive concept through the factors that shape it. The Reading Teacher, 69(2), 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. (2020). Causes and processes of formation of adult non-readers [Doctoral dissertation, Korea University]. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H., & Heo, M. (2021). A survey on reading performance and perception in adolescence: Focusing on the reasons for non-reading and aspects of smartphone use. Journal of Reading Research, 59, 9–50. (In Korean). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J. R., Ball, A., Geier, B. K., Parrila, R., & Wade-Woolley, L. (2011). The development of reading interest and its relation to reading ability. Journal of Research in Reading, 34(3), 263–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K. L. (2009). Reading motivation, perceptions of reading instruction and reading amount: A comparison of junior and senior secondary students in Hong Kong. Journal of Research in Reading, 32(4), 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, K. L. (2017). Reading motivation and strategy use of Hong Kong students: The role of reading instruction in Chinese language classes. In C. Ng, & B. Bartlett (Eds.), Improving reading and reading engagement in the 21st century (pp. 167–185). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S., & Kim, J. (2022). A study on the changes in reading interest of college students. Korean Language and Literature Education, 38, 69–103. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, D. J., Jr. (2002). The new literacies: Research on reading instruction with the Internet. In A. E. Farstrup, & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 310–336). International Reading Association. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J. (2001). The hidden worries of reading degradation: The influence of book culture and growth of adolescents. Curriculum, Teaching Material, and Method, 5, 45–49. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J., Li, Q., Sun, H., Huang, Z., & Zheng, G. (2021). Chinese secondary school students’ reading engagement profiles: Associations with reading comprehension. Reading and Writing, 34, 2257–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, J. (2010). Children’s access to print material and education-related outcomes: Findings from a meta-analytic review. Learning Point Associates. Available online: https://www.rif.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019/09/16/RIFandLearningPointMeta-FullReport.pdf (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Lo, Y., Mendell, N. R., & Rubin, D. B. (2001). Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika, 88(3), 767–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C. E., & Sun, B. (2018). “I’d still prefer to read the hard copy”: Adolescents’ print and digital reading habits. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(6), 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Mendelsohn, A. L. (2020). Children’s literacy experiences in low-income families: The content of books matters. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(2), 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Trautwein, U., & Morin, A. J. S. (2009). Classical latent profile analysis of academic self-concept dimensions: Synergy of person- and variable-centered approaches to theoretical models of self-concept. Structural Equation Modeling, 16(2), 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, B. G., & Stern, A. J. (2012). Café culture: Promoting empowerment and pleasure in adolescent literacy learning. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 51(4), 259–278. [Google Scholar]

- McGeown, S., Osborne, C., Warhurst, A., Norgate, R., & Duncan, L. (2016). Understanding children’s reading activities: Reading motivation, skills and child characteristics as predictors. Journal of Research in Reading, 39(1), 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M. C., Conradi, K., Lawrence, C., Jang, B. G., & Meyer, J. P. (2012). Reading attitudes of middle school students: Results of a U.S. survey. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(3), 283–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M. C., Kear, D. J., & Ellsworth, R. A. (1995). Children’s attitudes toward reading: A national survey. Reading Research Quarterly, 30(4), 934–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merga, M. K. (2014). Peer group and friend influences on the social acceptability of adolescent book reading. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57(6), 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merga, M. K. (2017). What motivates avid readers to maintain a regular reading habit in adulthood? Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 40(2), 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulecky, L. (1978, May 1–5). Aliteracy and a changing view of reading goals. The 23rd Annual Meeting of the International Reading Association, Houston, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 267–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, S. E., & Jolles, J. (2014). Reading enjoyment amongst non-leisure readers can affect achievement in secondary school. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, S., Pruslow, J., & Levitt, R. (2008). The reading habits and literacy attitudes of inservice and prospective teachers. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielen, T. M. (2016). Aliteracy: Causes and solutions [Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuizen, A. (2001). Young Australians reading: From keen to reluctant readers. Australian Centre for Youth Literature. [Google Scholar]

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. (2022). A study on the characteristics, formation, and deepening process of aliterate adolescent reader by type [Doctoral dissertation, Korea University]. (In Korean). [Google Scholar]

- Rogiers, A., Keer, H. V., & Merchie, E. (2020). The profile of the skilled reader: An investigation into the role of reading enjoyment and student characteristics. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salili, F., Chiu, C., & Lai, S. (2001). The influence of culture and context on students’ motivational orientation and performance. In F. Salili, C. Chiu, & Y. Hong (Eds.), Student motivation: The culture and context of learning (pp. 221–247). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Salter, A., & Brook, J. (2007). Are we becoming an aliterate society? The demand for recreational reading among undergraduates at two universities. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 14(3), 27–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefele, U., & Löweke, S. (2017). The nature, development, and effects of elementary students’ reading motivation profiles. Reading Research Quarterly, 53(4), 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H. W. (1992). Learning from Asian schools. Scientific American, 267(6), 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, M. (2017). A mixed-methods study of adolescents’ motivation to read. Teachers College Record, 119, 050306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, G. Y. (1992). Motivating reluctant readers: What can educators do? Reading Improvement, 29(1), 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Jia, L., & Jin, Y. (2020). Reading amount and reading strategy as mediators of the effects of intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation on reading achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 586346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, K., Andries, V., Howarth, D., Bonsall, J., Sabeti, S., & McGeown, S. (2020). Reading during adolescence: Why adolescents choose (or do not choose) books. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 64(2), 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H., Mo, D., Wang, H., Gao, Q., Shi, Y., Wu, P., Abbey, C., & Rozelle, S. (2018). Do resources matter? Effects of an in-class library project on student independent reading habits in primary schools in rural China. Reading Research Quarterly, 54(3), 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S., Zhang, M., & Sun, Y. (2019). Survey on the recreational reading of secondary school students. Educational Research Monthly, 11, 77–83. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

| Reading Interest Level in Different Periods | M | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Preschool | 3.40 | 2.52 | 0.80 | −0.15 | — | |||||

| 2 | 1–2 grades | 4.70 | 2.39 | 0.32 | −0.72 | 0.82 ** | — | ||||

| 3 | 3–4 grades | 5.99 | 2.40 | −0.06 | −0.89 | 0.64 ** | 0.80 ** | — | |||

| 4 | 5–6 grades | 6.84 | 2.26 | −0.49 | −0.48 | 0.40 ** | 0.54 ** | 0.76 ** | — | ||

| 5 | Middle school | 6.82 | 2.35 | −0.64 | −0.19 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.27 ** | 0.42 ** | — | |

| 6 | High school | 6.32 | 2.48 | −0.30 | −0.82 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.12 * | 0.43 ** | — |

| 7 | college | 6.57 | 2.40 | −0.63 | −0.18 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.12 * |

| Numbers of Profiles | Model Fit Indices | Size of the Smallest Group | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | FP | AIC | BIC | ABIC | LMRT (p) | Entropy | ||

| 1 | −5151.154 | 14 | 103,30.308 | 10,383.108 | 10,338.702 | — | — | 100.0% |

| 2 | −4876.121 | 22 | 9796.242 | 9879.213 | 9809.433 | 0.0000 | 0.860 | 47.6% |

| 3 | −4746.032 | 30 | 9552.065 | 9665.208 | 9570.053 | 0.0010 | 0.867 | 22.1% |

| 4 | −4696.055 | 38 | 9468.111 | 9611.426 | 9490.896 | 0.1881 | 0.864 | 13.1% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Zhao, M. Reading Interest Profiles Among Preservice Chinese Language Teachers: Why They Begin to Like (or Dislike) Reading. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081111

Wang X, Zhao M. Reading Interest Profiles Among Preservice Chinese Language Teachers: Why They Begin to Like (or Dislike) Reading. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081111

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaocheng, and Min Zhao. 2025. "Reading Interest Profiles Among Preservice Chinese Language Teachers: Why They Begin to Like (or Dislike) Reading" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081111

APA StyleWang, X., & Zhao, M. (2025). Reading Interest Profiles Among Preservice Chinese Language Teachers: Why They Begin to Like (or Dislike) Reading. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1111. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081111