The System of Corrective Interventions in the Sex Offender Population and the Proposed “Trident Statal Program” (TSP) in the Field of Italian Sex Crimes

Abstract

1. Sex Offenders: Definition; Psychosocial, Clinical, and Educational Contexts; And Risk of Recidivism

1.1. Introduction

- (1)

- Sexual abuse consists of any kind of nonconsensual sexual contact, regardless of age and gender, social status, or any other interpersonal differences. It is physical and/or verbal harassment that is limited to the use of inappropriate verbal conduct with sexual content or inappropriate sexual behavior without the use of force or violence.

- (2)

- Sexual assault consists of sexual abuse that materializes physical conduct with sexualizing value, with the use of force or violence, excluding penetrative acts.

- (3)

- Rape is sexual violence characterized by using force or violence in the performance of one or more repeated penetrative acts, with the male sex organ or any other body part or object, even unconventional.

1.2. Social, Clinical, and Educational Contexts

- (1)

- The “social-anthropological theories” (man as a social animal, patriarchy, social–familial context of reference, and control of territory for settlement) assume that man, being a social animal with selfish tendencies, is driven by a sense of dominance and possession, and therefore the use of force innately represents the highest expression of control to demonstrate his superiority.

- (2)

- The “psycho-educational theories” (behavioral learning, direct experience, and repetition of the act because of reinforcements) assume, on the other hand, that behavior is the consequence of the subjective, cognitive process of interpreting reality, and the repetition is derived from the reinforcements that, from time to time, have maintained or discouraged that conduct.

- (3)

- The “clinical theories” (the psychopathology and neurobiology of dysfunction) assume, finally, that behavior is the consequence of the subjective, cognitive process of interpreting reality, but that underlying it is a precise neurobiology of dysfunction arising from psychopathology.

1.3. Parameters of Intervention Success: Risk of Recidivism and Compensation

2. Methods, Aims, and Objectives

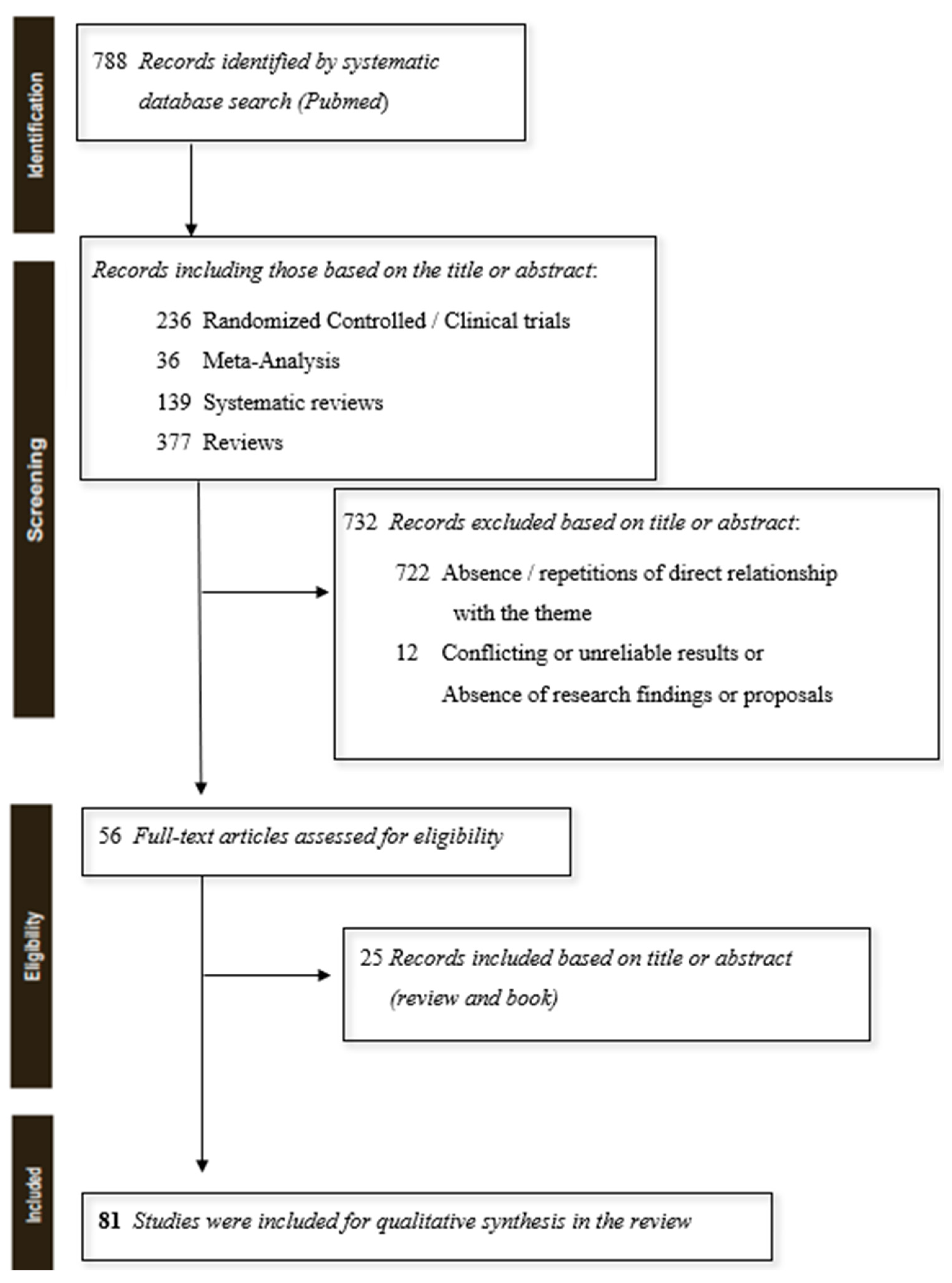

2.1. Methods

2.2. Aim and Objectives

3. Singular and Multidisciplinary Approaches: Lights and Shadows in Comparison

4. Individual and Collective Profile Management: The Principal Models Compared—A Methodological Discussion of the Introduction of a New Program

5. The Complexity of the Current Corrective Action System and the Proposal of the “Trident Statal Program” (TSP) in the Field of Sex Crimes: Theoretical Framework and Structural Model

5.1. Foreword

5.2. “Primary Intervention”: The Preventive System and the Pedagogical–Educational Model

- (1)

- Organization at the ministerial level of a specific educational policy (not modified) that provides for compulsory thematic meetings in middle–secondary schools to train the teaching staff and students about sexual offenses and defense tools.

- (2)

- Initiation of a psychological service desk in all school levels, regardless of grade, with the inclusion of at least one psychologist figure, framed by a national labor contract, with a permanent status, and with a managerial and organizational role, also supporting teaching and administration.

- (3)

- Centralized government management of policies to support the sex offender through participation in public calls for proposals with stringent legal requirements and making winning private organizations equal to public law entities, as supervised by the Ministry of Health.

5.3. “Secondary Intervention”: The Repressive System and the Criminological–Legal–Political Framework

- (1)

- Establishment of an inter-ministerial office dedicated to sex crimes, interfacing the Ministries of Education, Justice, and Public Security.

- (2)

- Tightening of the punishment regime for sex crimes, with repressive purposes and exclusion of rewards and sentence discounts.

5.4. “Tertiary Intervention”: The Clinical (Rehabilitation) System and the Biopsychosocial Model

- (1)

- Establishment of a personalized educational–training and clinical–psychological pathway, which is aimed at the re-education and reintegration of the sex offender already during the period of detention and throughout the subject’s life, with a follow-up function. The course must be educational in nature to enable the subject to find an independent personal and work placement in society, and it must be clinical in nature to offer him or her continuous personal support during and after the state of imprisonment and social reintegration.

- (2)

- Placement of the subject in the “Protection and Guardianship Program”, which gives a new personal identity to the sex offender and removes him or her from the social context of reference, to be reintegrated into a new neutral social–environmental context without, however, losing contact with close family members.

6. Methodological and Applicative Discussions

6.1. The Choice of the Model (Trident Statal Model, TSM)

6.2. Model Description

7. Limitations of the Model and Future Prospects

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Andrews, D. A., Dowden, C., & Rettinger, J. L. (2001). Special populations within corrections. In J. A. Winterdyk (Ed.), Corrections in Canada: Social reactions to crime. Prentice-Hall Press. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, D. A., Zinger, I., Hoge, R. D., Bonta, J., Gendreau, P., & Cullen, F. T. (1990). Does correctional treatment work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis. Criminology, 28, 369–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L., Walvisch, J., & Richards, K. (2019). More, longer, tougher… or is it finally time for a different approach to the post-sentence management of sex offenders in Australia? Criminal Law Journal, 43, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, L., & Weatherburn, D. (2020). Building community confidence in community corrections. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 32, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchette, K., & Brown, S. L. (2006). The assessment and treatment of women offenders: An integrative perspective. John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. A. (2016). The psychology of criminal conduct (6th ed.). Routledge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borduin, C. M., Schaeffer, C. M., & Heiblum, N. (2009). A randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders: Effects on youth social ecology and criminal activity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camaldo, F. (2024). Questioni attuali di giustizia penale europea e internazionale. Giappichelli Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Cellini, R. (2019). Politica economica. In Introduzione ai modelli fondamentali. McGraw-Hill Edu. [Google Scholar]

- Corson, C. (2010). Shifting environmental governance in a neoliberal world: US AID for conservation. Antipode, 42(3), 576–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K., Evans, M., & Lorber, J. (2020). Handbook of gender and women’s studies. SAGE Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Deaton, A., & Cartwright, N. (2017). Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Social Science & Medicine, 210, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, J. (2019). La giustizia penale negoziata in Europa. Cedam Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, J. A., Khan, O., Ferriter, M., Huband, N., Powney, M. J., & Duggan, C. (2012). Psychological interventions for adults who have sexually offended or are at risk of offending. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, CD007507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowden, C., & Andrews, D. A. (1999). What works in young offender treatment: A meta-analysis. Forum on Corrections Research, 11, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Eher, R., Olver, M. E., Heurix, I., Schilling, F., & Rettenberger, M. (2015). Predicting reoffense in pedophilic child molesters by clinical diagnoses and risk assessment. Law and Human Behavior, 39(6), 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanchiotti, V. (2021). La giustizia penale statunitense. Giappichelli. [Google Scholar]

- Fanniff, A. M., & Becker, J. V. (2006). Specialized assessment and treatment of adolescent sex offenders. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(3), 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrington, D. P. (2019). The development of violence from age 8 to 61. Aggressive Behavior, 45(4), 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H., Ormrod, R., Hamby, S., & Krake, K. (2009). Children’s exposure to violence: A comprehensive national survey (NCJ 227744). Retrieved from the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention). Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, K. (2015). Theorizing community integration as desistance-promotion. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 2(1), 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K. (2016). Civic commitment: Promoting desistance through community integration. Punishment & Society, 18(1), 68–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbard, G. O. (2015). Psichiatria psicodinamica (V ed.). Raffaello Cortina Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, M., McMahan, R. W., & Schoenbaum, G. (1999). Orbitofrontal cortex and representation of incentive value in associative learning. Journal of Neuroscience, 19(15), 6610–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gannon, T. A., Olver, M. E., Mallion, J. S., & James, M. (2019). Does specialized psychological treatment for offending reduce recidivism? A meta-analysis examining staff and program variables as predictors of treatment effectiveness. Clinical Psychology Review, 73, 101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, R. K., & Bourgon, G. (2007, June 8). A psychologically informed meta-analysis of sex offender treatment. 68th Annual Convention of the Canadian Psychological Association, Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, D. (2017). Desistance from sexual offending: Narratives of retirement, regulation, and recovery. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kemshall, H. (2017). The historical evolution of sex offender risk management. In K. McCartan, & H. Kemshall (Eds.), Contemporary sex offender management (Vol. 1). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., Roth, W. T., & Wollburg, E. (2015). Effects of therapeutic relationship, expectancy, and credibility in breathing therapies for anxiety. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 79(2), 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knack, N., Winder, B., Murphy, L., & Fedoroff, J. P. (2019). Primary and secondary prevention of child sexual abuse. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(2), 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koss, M. (2014). The RESTORE program of restorative justice for sex crimes: Vision, process, and outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(9), 1623–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainer, M. M. (2014). Epidemiological criminology (EpiCrim): Definition and application. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Criminology, 2(1), 63–103. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, E. T., & Dwyer, R. G. (2018). Psychosis and sexual offending: A review of current literature. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(11), 3372–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereaux, P., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(10), e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, F., Link, E., Schmucker, M., Bender, D., Breuer, M., Carl, L., Endres, J., & Lauchs, L. (2020). On the effectiveness of sexual offender treatment in prisons: A comparison of two different evaluation designs in routine practice. Sexual Abuse, 32(4), 452–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lösel, F., & Schmucker, M. (2005). The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotta, G., & Cornacchia, I. (2021). Criminologia. Storia, teorie, metodi. Cedam Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, W. L., Marshall, L. E., Serran, G. A., & O’Brien, M. D. (2011). Rehabilitating sexual offenders: A strength-based approach. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew, L. M., Martin, J. L., Friedlander, M. L., Shaffer, K., Breland, J. Y., Slotkin, S., & Leventhal, H. (2019). The common sense of counseling psychology: Introducing the common-sense model of self-regulation. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 31(4), 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartan, K., Harris, D. A., & Prescott, D. S. (2019). Seen and not heard: The service user’s experience through the justice system of individuals convicted of sexual offenses. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 65(12), 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartan, K., & Kemshall, H. (2020). The potential role of recovery capital instopping sexual offending: Lessons from circles of support and accountability to enrich practice. Irish Probation Journal, 17, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- McCartan, K., & Kemshall, H. (2021). Incorporating quaternary prevention: Understanding the full scope of public health practices in sexual abuse prevention. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 67, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartan, K., & Richards, K. (2021). The integration of people convicted of a sexual offence into the community and their (risk) management. Current Psychiatry Reports, 23, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartan, K., Uzieblo, K., & Smid, W. J. (2021). Professionals’ understandings of and attitudes to the prevention of sexual abuse: An international exploratory study. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 65(8), 815–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlynn, C., Westmarland, N., & Godden, N. (2012). ‘I just wanted him to hear me’: Sexual violence and the possibilities of restorative justice. Journal of Law and Society, 39, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, P. J., Lingley-Pottie, P., Emberly, D. J., Thurston, C., & McLean, C. (2009). Integrated knowledge translation in mental health: Family help as an example. Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18(1), 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mews, A., Di Bella, L., & Purver, M. (2017). Impact evaluation of the prison-based core sex offender treatment programme. (Ministry of Justice analytical series). Ministry of Justice. [Google Scholar]

- Mokros, A., & Banse, R. (2019). The “Dunkelfeld” project for self-identified pedophiles: A reappraisal of its effectiveness. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(5), 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moulden, H. M., Abracen, J., Looman, J., & Kingston, D. A. (2020). The role of major mental illness in problematic sexual behavior: Current perspectives and controversies. In The Wiley handbook of what works with sexual offenders: Contemporary perspectives in theory, assessment, treatment, and prevention. Wiley Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moulden, H. M., & Marshall, L. (2017). Major mental illness in those who sexually abuse. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mpofu, E., Athanasou, J. A., Rafe, C., & Belshaw, S. H. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy efficacy for reducing recidivism rates of moderate-and high-risk sexual offenders: A scoping systematic literature review. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(1), 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, P. (2019). Child sexual abuse and media: Coverage, representation, and advocacy. Institutionalized Children Explorations and Beyond, 6(1), 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olver, M. E., Marshall, L. E., Marshall, W. L., & Nicholaichuk, T. P. (2020). A longterm outcome assessment of the effects on subsequent reoffense rates of a prison-based CBT/RNR sex offender treatment program with strength-based elements. Sexual Abuse, 32(2), 127–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C., & Thornhill, R. A. (2000). Natural history of rape. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta, G. (2019). Paraphilic disorder: Definition, contexts and clinical strategies. Neuro Research, 1(1), 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. (2020). Dysfunctional sexual behaviours: Definition, clinical contexts, neurobiological profiles and treatments. International Journal of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care, 3(1), 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. (2021). Sexual fantasies: The boundary between physiology and psychopathology. Clinical evidence. International Journal of Sexual and Reproductive Health Care, 4(1), 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. (2023). The concept of “hypersexuality” in the boundary between physiological and pathological sexuality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(10), 5844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. (2024a). The acquisition of a new social norm, the social conditioning, and the subjective role of structural and functional personality profile. Pilot study. MSD International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health, 3(1), 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G. (2024b). “Perrotta Integrative Clinical Interviews-3” (PICI-3): Development, regulation, updation, and validation of the psychometric instrument for the identification of functional and dysfunctional personality traits and diagnosis of psychopathological disorders, for children (8–10 years), preadolescents (11–13 years), adolescents (14–18 years), adults (19–69 years), and elders (70–90 years). Ibrain, 10(2), 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, G., & Marciano, A. (2022). The clinical boundary between deviant behavior and criminal conduct: From maladaptive positions to pathological dysfunctionality using the “Graded Antisociality Model” (GA-M), the “Antisocial Severity Scale” (AS-S) and “Perrotta-Marciano questionnaire on the grade of awareness of one’s deviant and criminal behaviors” (ADCB-Q). Annals of Psychiatry and Treatment, 6(1), 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruccelli, I., Pedata, L., & D’Urso, G. (2018). L’autore di reati sessuali. Percorsi di valutazione e trattamento. Franco Angeli Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Popović, S. (2018). Child sexual abuse news: A systematic review of content analysis studies. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 27(7), 752–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proulx, J., Cortoni, F., Craig, L. A., & Letourneau, E. J. (2020). The Wiley handbook of what works with sexual offenders: Contemporary perspectives in theory, assessment, treatment, and prevention. Wiley Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pycroft, A., & Gough, D. (2019). Multi-agency working in criminal justice: Theory, policy and practice (2nd ed.). Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, T. (2017). The Oxford handbook of sex offences and sex offenders. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J. H., & Jessel, T. M. (2014). Principi di neuroscienze. CEA ed. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, M. C., Wood, J. M., Babchishin, K. M., & Flynn, S. (2012). Online solicitation offenders are different from child pornography offenders and lower risk contact sexual offenders. American Psychological Association, 36(4), 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonelli, C., D’Urso, G., & D’Angiò, G. (2024). Manuale di psicologia dello sviluppo psicoaffettivo e sessuale. Erickson Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S. G., Basile, K. C., Gilbert, L. K., Merrick, M. T., Patel, N., Walling, M., & Jain, A. (2017). The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010–2012 state report. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, J., McCartan, K., & Panaro, R. (2016). Changing course: From a victim/offender duality to a public health perspective. In R. Laws, & W. O’Donoghue (Eds.), Treatment of sex offenders: Strengths and weaknesses in assessment and intervention. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, T. (2016). Policing sexual offences and sex offenders. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, N., Gannon, T. A., & Olver, M. E. (2021). Does treatment for sexual offending work? Current Psychiatry Reports, 23, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeling, H., & Saloo, F. (2018). An exploratory study of the experiences of a small sample of men convicted of sexual offences who have reoffended after participating in prison-based treatment. HM prison & probation: Analytical summary. Available online: http://researchgate.net/publication/377108313_An_exploratory_study_of_the_experiences_of_a_small_sample_of_men_convicted_of_sexual_offences_who_have_reoffended_after_participating_in_prison-based_treatment (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Walker, S. J. L., Hester, M., & Rumney, P. (2019). Rape, inequality and the criminal justice response in England: The importance of age and gender. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 21(3), 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, L., Dreher, T., Hess, K., McCallum, K., & Skogerbø, E. (2020). Media hierarchies of attention: News values and Australia’s royal commission into institutional responses to child sexual abuse. Journalism Studies, 21(2), 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltermaurer, E., & Akers, T. A. (2013). Epidemiological criminology: Theory to practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L. M. (2003). Understanding the role of entertainment media in the sexual socialization of American youth: A review of empirical research. Developmental Review, 23(3), 347–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijetunga, C., Picard, E., & Rosenfeld, B. (2019). Management of sex offenders in community settings. In Sexually violent predators: A clinical science handbook. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Zara, G. (2016). Valutare il rischio in ambito criminologico. In Procedure e strumenti per l’assessment psicologico. Il Mulino Ed. [Google Scholar]

| Approach | Description |

|---|---|

| Cognitive–Behavioral Therapy (CBT) | This approach is used in many therapeutic programs for sex offenders to prevent relapse. CBT combines two strategies to address both thoughts/conceptions and behaviors/actions, focusing work on one’s perceived (and thus cognitive focus), reinforcing patterns of behavior, while the behavioral component emphasizes actions that contribute to the act. This problem-centered approach helps sex offenders learn new skills and develop competencies to maintain appropriate behaviors through cognitive–behavioral deconstruction and restructuring work (Kim et al., 2015; McGrath et al., 2009). Treatment programs involve various strategies that focus on correcting thoughts and emotions, regulating behaviors, and prosocial beliefs. CBT is also the most popular treatment approach for adolescent sex offenders and is widely supported (Corson, 2010). |

| Multisystemic Therapy (MST) | This approach has also been successful in treating sex offenders (Borduin et al., 2009). Originally developed by Scott Henggeler as a family treatment program for antisocial children and serious offenders, it has evolved over time to work on adolescent socialization and interpersonal relationships, focusing on breaking the cycle of sexual violence to develop a safety plan (Fanniff & Becker, 2006). MST thus works on the systemic–relational aspects, and that is precisely why when combined with CBT more results are achieved (Seto et al., 2012). |

| Additional Sex Offender Treatments (ASOTs) | In addition to psychotherapies, sex offenders may also receive specific surgical (mechanical castration) and/or pharmacological (chemical castration) therapy. Specifically, the latter refers to hormonal drugs such as antiandrogens, which are used to reduce sexual arousal, although studies show that combination with psychotherapy is the best treatment choice, also considering the high rate of refusal or renunciation of drug therapies by patients (Gallagher et al., 1999). The paucity of studies related to mechanical castration leads to the inference that this practice is not conclusive (Eher et al., 2015). |

| Model | Author | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk–Need–Responsivity (RNR) | Andrews et al. (1990); Blanchette and Brown (2006) | It was a widely used model of rehabilitation in the 1990s and 2000s, structured during the 1960s and 1970s, that focuses almost exclusively on risk reduction (recidivism) and the need to eliminate or reduce the consequences of harmful behaviors. There are three principles that should guide interventions: risk of recidivism, need to offend, and subjective reactivity. There is also an interaction with offender attributes; depending, for example, on age, gender, cognitive ability, or motivation, different types of interventions are indicated. | Failure to identify elements capable of motivating the subject to not reoffend. |

| Good Lives (GLM) | Ward (2003) | It was created to compensate for the shortcomings of the RNR and is presented as a rehabilitation model that focuses both on reducing the risk of recidivism and motivating the subject to stop reoffending sexually. The GLM, complementing RNR, provides a framework to help individuals build healthy, prosocial lifestyles aligned with their values and priorities, as opposed to the harmful behaviors for which they have been legally convicted. The Model accommodates the principles of risk, need, and responsivity, as it views a subject’s dynamic risk factors as signals of his or her lack of the ability to achieve so-called primary human goods (such as relationships, mastery, inner peace, and autonomy) in a prosocial manner. Dynamic risk factors are then addressed in the broader attempt to strengthen the client’s ability to achieve valuable goods through the acquisition of internal (skills and knowledge) and external resources (social supports, vocational training). | Motivation not to reoffend may depend on or be constantly reinforced by a dysfunctional or severe pathological personality structure, and therefore does not guarantee absolute certainty that the intervention will be successful in the long run. |

| Epidemiological crimino-logy (EpiCrim) | Waltermaurer and Akers (2013) | It integrates the previous models and seeks to respond to the issue of crime using a socio-environmental and clinical (public health and psychiatric) schema, which operates at both the individual/interpersonal and community/social levels through four stages of prevention (primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary). It emphasizes the importance of the individual, his or her relationships, and social context to better understand his or her pathways to crime and develop rehabilitation programs tailored to the person. | While working on both subjective and collective profiles, positive certainty of intervention is not guaranteed, as the individual motivational process comes into crisis at the time when the subject is the most vulnerable. |

| Pillar of Intervention | Area of Focus (System) | Type of Intervention | Description and Individual Proposed Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary intervention | Preventive system | Pedagogical–educational | This intervention is based on the preventive principle of educational action and is dedicated to both the person who has not committed the sexual offense and the person who might commit it because he or she has a criminal inclination (both with a formative–educational function); its actions are listed below:

|

| Secondary intervention | Repressive system | Criminological–legal–political | This intervention is based on the repressive principle of legal action, as follows:

|

| Tertiary intervention | Clinical system | Biopsychosocial | This intervention is based on the rehabilitative principle of psychosocial action and is entirely dedicated to the sex offender (with reintegrative function), as follows:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Perrotta, G.; Eleuteri, S.; Grilli, S.; D’Urso, G.; Petruccelli, I. The System of Corrective Interventions in the Sex Offender Population and the Proposed “Trident Statal Program” (TSP) in the Field of Italian Sex Crimes. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081085

Perrotta G, Eleuteri S, Grilli S, D’Urso G, Petruccelli I. The System of Corrective Interventions in the Sex Offender Population and the Proposed “Trident Statal Program” (TSP) in the Field of Italian Sex Crimes. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081085

Chicago/Turabian StylePerrotta, Giulio, Stefano Eleuteri, Simona Grilli, Giulio D’Urso, and Irene Petruccelli. 2025. "The System of Corrective Interventions in the Sex Offender Population and the Proposed “Trident Statal Program” (TSP) in the Field of Italian Sex Crimes" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081085

APA StylePerrotta, G., Eleuteri, S., Grilli, S., D’Urso, G., & Petruccelli, I. (2025). The System of Corrective Interventions in the Sex Offender Population and the Proposed “Trident Statal Program” (TSP) in the Field of Italian Sex Crimes. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1085. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081085