Does Parental Media Soothing Lead to the Risk of Callous–Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood? Testing a Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Media Soothing and Children’s CU Behaviors

1.2. Children’s Emotion Regulation as the Mediator

1.3. Children’s Effortful Control as the Moderator

1.4. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Media Soothing

2.2.2. Emotion Regulation

2.2.3. CU Behaviors

2.2.4. Effortful Control

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Testing for Common Method Bias

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis of Variables

3.3. Testing the Indirect Effect Through Emotion Regulation

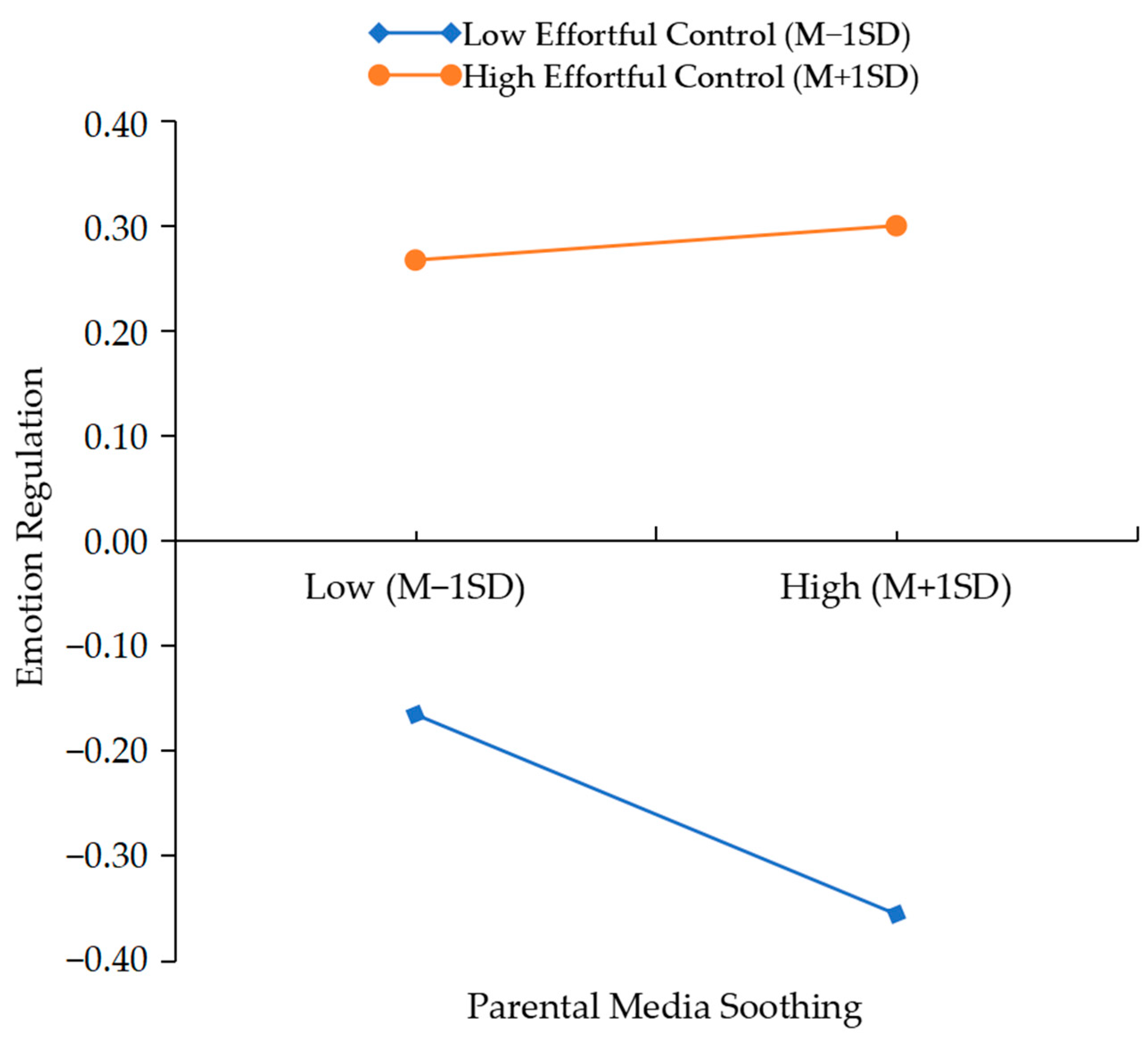

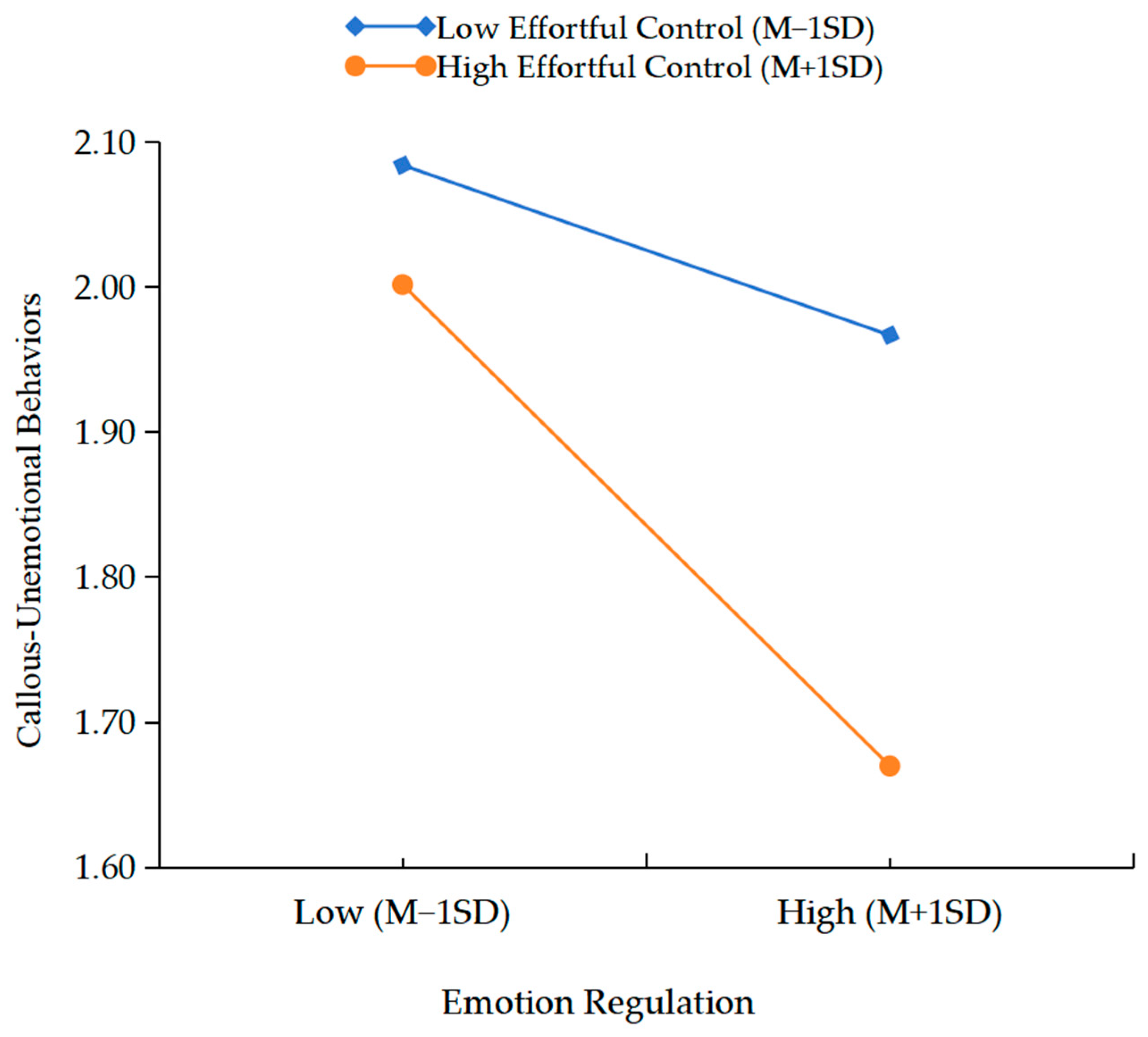

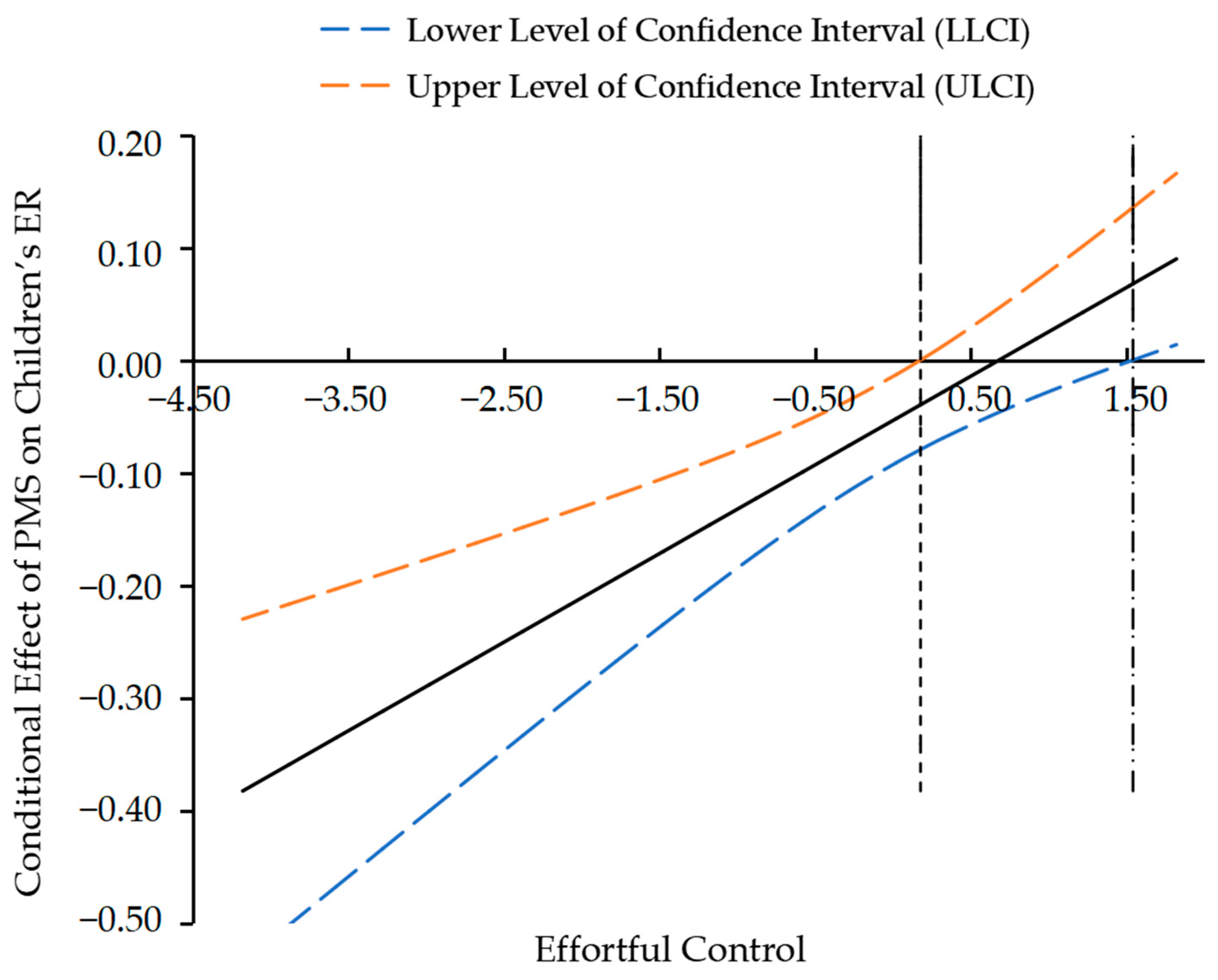

3.4. Testing the Difference in the Indirect Impact According to the Level of Effortful Control

4. Discussion

4.1. Parental Media Soothing Acts as the Potential Risk Factor for Early CU Behaviors

4.2. The Indirect Impact Through Children’s Emotion Regulation Ability Potentially

4.3. Effortful Control Matters Significantly for Early Socioemotional Development

5. Conclusions and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allan, N. P., Lonigan, C. J., & Wilson, S. B. (2013). Psychometric evaluation of the children’s behavior questionnaire-very short form in preschool children using parent and teacher report. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(2), 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. R., & Hanson, K. G. (2017). Screen media and parent-child interactions. In R. Barr, & D. N. Linebarger (Eds.), Media exposure during infancy and early childhood: The effects of content and context on learning and development (pp. 173–194). Springer International Publishing/Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arık, G. K. (2024). Predictors of media emotion regulation and its consequences for children’s socioemotional development. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar, 16(3), 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunstein, L. M., Gross, J. J., & Ochsner, K. N. (2017). Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: A multi-level framework. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(10), 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X., Somerville, M. P., & Allen, J. L. (2023). Teachers’ perceptions of the school functioning of Chinese preschool children with callous-unemotional traits and disruptive behaviors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 123, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapito, E., Ribeiro, M. T., Pereira, A. I., & Roberto, M. S. (2020). Parenting stress and preschoolers’ socio-emotional adjustment: The mediating role of parenting styles in parent–child dyads. Journal of Family Studies, 26(4), 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W., Li, D., Bao, Z., Yan, Y., & Zhou, Z. (2015). The impact of parent-child attachment on adolescent problematic internet use: A moderated mediation model. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 47(5), 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christakis, D. A. (2014). Interactive media use at younger than the age of 2 years: Time to rethink the American Academy of Pediatrics guideline? JAMA Pediatrics, 168(5), 399–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciucci, E., Baroncelli, A., Franchi, M., Golmaryami, F. N., & Frick, P. J. (2014). The association between callous-unemotional traits and behavioral and academic adjustment in children: Further validation of the Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(2), 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S. M., Reschke, P. J., Stockdale, L., Gale, M., Shawcroft, J., Gentile, D. A., Brown, M., Ashby, S., Siufanua, M., & Ober, M. (2023). Silencing screaming with screens: The longitudinal relationship between media emotion regulation processes and children’s emotional reactivity, emotional knowledge, and empathy. Emotion, 23(8), 2194–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S. M., Rogers, A., Shawcroft, J., Reschke, P., Barr, R., Davis, E. J., Holmgren, H. G., & Domoff, S. (2022). Meltdowns and media: Moment-to-moment fluctuations in young children’s media use transitions and the role of children’s mood states. Computers in Human Behavior, 136, 107360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, S. M., Shawcroft, J., Gale, M., Gentile, D. A., Etherington, J. T., Holmgren, H., & Stockdale, L. (2021). Tantrums, toddlers and technology: Temperament, media emotion regulation, and problematic media use in early childhood. Computers in Human Behavior, 120, 106762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A. G., Barretto, C., Tasker, K., Ioane, J., & Lambie, I. (2025). Callous but in control: The effect of emotion regulation on callous traits in a sample of New Zealand youth. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S. G., Goulter, N., & Moretti, M. M. (2021). A systematic review of primary and secondary callous-unemotional traits and psychopathy variants in youth. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 24(1), 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadds, M. R., El Masry, Y., Wimalaweera, S., & Guastella, A. J. (2008). Reduced eye gaze explains “fear blindness” in childhood psychopathic traits. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(4), 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalope, K. A., & Woods, L. J. (2018). Digital media use in families: Theories and strategies for intervention. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27(2), 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danet, M., Miller, A. L., Weeks, H. M., Kaciroti, N., & Radesky, J. S. (2022). Children aged 3–4 years were more likely to be given mobile devices for calming purposes if they had weaker overall executive functioning. Acta Paediatrica, 111(7), 1383–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E. L., Quiñones-Camacho, L. E., & Buss, K. A. (2016). The effects of distraction and reappraisal on children’s parasympathetic regulation of sadness and fear. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 142, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q. W., Ding, C. X., Liu, M. L., Deng, J. X., & Wang, M. C. (2016). Psychometric properties of the inventory of callous-unemotional in preschool students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24(4), 663–666. [Google Scholar]

- Di Giunta, L., Lunetti, C., Fiasconaro, I., Gliozzo, G., Salvo, G., Ottaviani, C., Aringolo, K., Comitale, C., Riccioni, C., & D’Angeli, G. (2021). COVID-19 impact on parental emotion socialization and youth socioemotional adjustment in Italy. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(3), 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 665–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizur, Y., Somech, L. Y., & Vinokur, A. D. (2017). Effects of parent training on callous-unemotional traits, effortful control, and conduct problems: Mediation by parenting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(1), 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, C., Harvey, E., Cristini, E., Laurent, A., Lemelin, J. P., & Garon-Carrier, G. (2022). Is the association between early childhood screen media use and effortful control bidirectional? A prospective study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 918834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frick, P. J. (2004). Inventory of callous-unemotional traits [Unpublished rating scale]. University of New Orleans. [Google Scholar]

- Frick, P. J. (2009). Extending the contruct of psychopathy to youth: Implications for understanding, diagnosing, and treating antisocial children and adolescents. The Canadian Psychiatric Association Journal, 54(12), 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon-Hacker, A., & Gueron-Sela, N. (2020). Maternal use of media to regulate child distress: A double-edged sword? Longitudinal links to toddlers’ negative emotionality. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 23(6), 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, P. A., Landis, T., Maharaj, A., Ros-Demarize, R., Hart, K. C., & Garcia, A. (2022). Differentiating preschool children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional behaviors through emotion regulation and executive functioning. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 51(2), 170–182. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J. J. (2014). Emotion regulation: Conceptual and empirical foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (2nd ed., pp. 3–20). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hepach, R., & Vaish, A. (2020). The study of prosocial emotions in early childhood: Unique opportunities and insights. Emotion Review, 12(4), 278–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollister-Wagner, G. H., Foshee, V. A., & Jackson, C. (2001). Adolescent aggression: Models of resiliency. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, R., Zabatiero, J., Zubrick, S. R., Silva, D., & Straker, L. (2021). The association of mobile touch screen device use with parent-child attachment: A systematic review. Ergonomics, 64(12), 1606–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Bush, N. R. (2011). Temperament variation in sensitivity to parenting: Predicting changes in depression and anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(8), 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimonis, E. R., Frick, P. J., Fazekas, H., & Loney, B. R. (2006). Psychopathy, aggression, and the processing of emotional stimuli in non-referred girls and boys. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 24(1), 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim-Spoon, J., Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (2013). A longitudinal study of emotion regulation, emotion lability-negativity, and internalizing symptomatology in maltreated and nonmaltreated children. Child Development, 84(2), 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanska, G., & Kim, S. (2013). Difficult temperament moderates links between maternal responsiveness and children’s compliance and behavior problems in low-income families. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(3), 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochanska, G., & Knaack, A. (2003). Effortful control as a personality characteristic of young children: Antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Personality, 71(6), 1087–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konok, V., Binet, M. A., Korom, Á., Pogány, Á., Miklósi, Á., & Fitzpatrick, C. (2024). Cure for tantrums? Longitudinal associations between parental digital emotion regulation and children’s self-regulatory skills. Frontiers in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 3, 1276154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengua, L. J., Bush, N. R., Long, A. C., Kovacs, E. A., & Trancik, A. M. (2008). Effortful control as a moderator of the relation between contextual risk factors and growth in adjustment problems. Development and Psychopathology, 20(2), 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linder, L. K., McDaniel, B. T., Stockdale, L., & Coyne, S. M. (2021). The impact of parent and child media use on early parent–infant attachment. Infancy, 26(4), 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Yang, Y., Geng, J., Cai, T., Zhu, M., Chen, T., & Xiang, J. (2022). Harsh parenting and children’s aggressive behavior: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q., & Wang, Z. (2021). Associations between parental emotional warmth, parental attachment, peer attachment, and adolescents’ character strengths. Children and Youth Services Review, 120, 105765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Wu, X., Huang, K., Yan, S., Ma, L., Cao, H., Gan, H., & Tao, F. (2021). Early childhood screen time as a predictor of emotional and behavioral problems in children at 4 years: A birth cohort study in China. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, 26(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manole, S., & Enea, V. (2024). Emotion regulation difficulties and callous-unemotional traits: The role of guilt across samples of incarcerated male adult offenders. Deviant Behavior, 46(4), 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, A. A., Finger, E. C., Schechter, J. C., Jurkowitz, I. T. N., Reid, M. E., & Blair, R. J. R. (2011). Adolescents with psychopathic traits report reductions in physiological responses to fear. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(8), 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihic, J., & Novak, M. (2018). Importance of child emotion regulation for prevention of internalized and externalized problems. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 7(2), 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Mirabile, S. P., Oertwig, D., & Halberstadt, A. G. (2018). Parent emotion socialization and children’s socioemotional adjustment: When is supportiveness no longer supportive? Social Development, 27(3), 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelen, D., Shaffer, A., & Suveg, C. (2016). Maternal emotion regulation: Links to emotion parenting and child emotion regulation. Journal of Family Issues, 37(13), 1891–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. S., Criss, M. M., Silk, J. S., & Houltberg, B. J. (2017). The impact of parenting on emotion regulation during childhood and adolescence. Child Development Perspectives, 11(4), 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, A. S., Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., Myers, S. S., & Robinson, L. R. (2007). The role of the family context in the development of emotion regulation. Social Development, 16(2), 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2015). Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills (pp. 35–53). OECD Publishing. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/skills-for-social-progress_9789264226159-en.html (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Paulus, F. W., Ohmann, S., Möhler, E., Plener, P., & Popow, C. (2021). Emotional dysregulation in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. A narrative review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 628252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, S. P., & Rothbart, M. K. (2006). Development of short and very short forms of the children’s behavior questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 87(1), 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J. S., Kaciroti, N., Weeks, H. M., Schaller, A., & Miller, A. L. (2023). Longitudinal associations between use of mobile devices for calming and emotional reactivity and executive functioning in children aged 3 to 5 years. JAMA Pediatrics, 177(1), 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J. S., Peacock-Chambers, E., Zuckerman, B., & Silverstein, M. (2016). Use of mobile technology to calm upset children: Associations with social-emotional development. JAMA Pediatrics, 170(4), 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radesky, J. S., Silverstein, M., Zuckerman, B., & Christakis, D. A. (2014). Infant self-regulation and early childhood media exposure. Pediatrics, 133(5), e1172–e1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radesky, J. S., Weeks, H. M., Ball, R., Schaller, A., Yeo, S., Durnez, J., Tamayo-Rios, M., Epstein, M., Kirkorian, H., Coyne, S., & Barr, R. (2020). Young children’s use of smartphones and tablets. Pediatrics, 146(1), e20193518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, M. B., Neufeld, R. W. J., Yoon, M., Li, A., & Mitchell, D. G. V. (2022). Predicting youth aggression with empathy and callous unemotional traits: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 98, 102186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, G. D., Dobrean, A., & Florean, I. S. (2024). Explaining the “parenting—Callous-unemotional traits—Antisocial behavior” axis in early adolescence: The role of affiliative reward. Development and Psychopathology, 36(4), 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbart, M. K., Sheese, B. E., & Conradt, E. D. (2009). Childhood temperament. In P. J. Corr, & G. Matthews (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of personality psychology (pp. 177–190). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, H. J. V., Wallace, N. S., Laurent, H. K., & Mayes, L. C. (2015). Emotion regulation in parenthood. Developmental Review, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M. N., Pons, F., & Molina, P. (2014). Emotion regulation strategies in preschool children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 32(4), 440–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana-Vega, L., Gómez-Muñoz, A., & Feliciano-García, L. (2019). Adolescents problematic mobile phone use, fear of missing out and family communication. Comunicar, 27(59), 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S. A., & Hakim-Larson, J. (2021). Temperament, emotion regulation, and emotion-related parenting: Maternal emotion socialization during early childhood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(10), 2353–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, A., & Cicchetti, D. (1997). Emotion regulation among school-age children: The development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology, 33(6), 906–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonds, J., Kieras, J. E., Rueda, M. R., & Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Effortful control, executive attention, and emotional regulation in 7–10-year-old children. Cognitive Development, 22(4), 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skalická, V., Wold Hygen, B., Stenseng, F., Kårstad, S. B., & Wichstrøm, L. (2019). Screen time and the development of emotion understanding from age 4 to age 8: A community study. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 37(3), 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, A. L., Taylor, L. B., & Cingel, D. P. (2025). The family context and the use of media for emotion regulation during early childhood: Testing the tripartite model of children’s emotion regulation and adjustment. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 34, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, A. E., Oblath, R., Sheldrick, R. C., Ng, L. C., Silverstein, M., & Garg, A. (2022). Social determinants of health and ADHD symptoms in preschool-age children. Journal of Attention Disorders, 26(3), 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockdale, L. A., Coyne, S. M., & Padilla-Walker, L. M. (2018). Parent and child technoference and socioemotional behavioral outcomes: A nationally representative study of 10- to 20-year-old adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 88, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sznycer, D., Sell, A., & Lieberman, D. (2021). Forms and functions of the social emotions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(4), 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ştefan, C. A., & Avram, J. (2018). The multifaceted role of attachment during preschool: Moderator of its indirect effect on empathy through emotion regulation. Early Child Development and Care, 188(1), 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R., Guo, X., Chen, S., He, G., & Wu, X. (2023). Callous-unemotional traits and externalizing problem behaviors in left-behind preschool children: The role of emotional lability/negativity and positive teacher-child relationship. Child And Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17(1), 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M. J., Davies, P. T., Hentges, R. F., Sturge-Apple, M. L., & Parry, L. Q. (2020). Understanding how and why effortful control moderates children’s vulnerability to interparental conflict. Developmental Psychology, 56(5), 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, K. C., Richardson, C. G., Gadermann, A. M., Emerson, S. D., Shoveller, J., & Guhn, M. (2019). Association of childhood social-emotional functioning profiles at school entry with early-onset mental health conditions. JAMA Network Open, 2(1), e186694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truedsson, E., Fawcett, C., Wesevich, V., Gredebäck, G., & Wåhlstedt, C. (2019). The role of callous-unemotional traits on adolescent positive and negative emotional reactivity: A longitudinal community-based study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzundağ, B. A., Oranç, C., Keşşafoğlu, D., & Altundal, M. N. (2022). How children in Turkey use digital media: Factors related to children, parents, and their home environment. In Childhood in Turkey: Educational, sociological, and psychological perspectives (pp. 137–149). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vroman, L. N., & Durbin, C. E. (2015). High effortful control is associated with reduced emotional expressiveness in young children. Journal of Research in Personality, 58, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R., Gardner, F., Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., Wilson, M. N., & Hyde, L. W. (2015). Callous-unemotional behavior and early-childhood onset of behavior problems: The role of parental harshness and warmth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 44(4), 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R., Gardner, F., Viding, E., Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., Wilson, M. N., & Hyde, L. W. (2014). Bidirectional associations between parental warmth, callous unemotional behavior, and behavior problems in high-risk preschoolers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R., & Hyde, L. W. (2017). Callous–unemotional behaviors in early childhood: Measurement, meaning, and the influence of parenting. Child Development Perspectives, 11(2), 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, R., & Hyde, L. W. (2018). Callous-unemotional behaviors in early childhood: The development of empathy and prosociality gone awry. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, E. E. (2000). Protective factors and individual resilience. In J. P. Shonkoff, & S. J. Meisels (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood intervention (2nd ed., pp. 115–132). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, S. F., & Frick, P. J. (2010). Callous-unemotional traits and their importance to causal models of severe antisocial behavior in youth. In R. T. Salekin, & D. R. Lynam (Eds.), Handbook of child and adolescent psychopathy (pp. 135–155). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilke, J., Bäker, N., Bolz, T., & Eilts, J. (2025). Analyzing the link between callous-unemotional traits and internalizing and externalizing behavior problems: The crucial role of emotion regulation skills. Deviant Behavior. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, J., & Goagoses, N. (2023). Morality in middle childhood: The role of callous-unemotional traits and emotion regulation skills. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. J., Dauterman, H. A., Frey, K. S., Rutter, T. M., Myers, J., Zhou, V., & Bisi, E. (2021). Effortful control moderates the relation between negative emotionality and socially appropriate behavior. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 207, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winebrake, D. A., Huth, N., Gueron-Sela, N., Propper, C., Mills-Koonce, R., Bedford, R., & Wagner, N. J. (2024). An examination of the relations between effortful control in early childhood and risk for later externalizing psychopathology: A bi-factor structural equation modeling approach. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Yu, J., & Xu, C. (2023). Does screen exposure necessarily relate to behavior problems? The buffering roles of emotion regulation and caregiver companionship. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 63, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. C., & Kyranides, M. N. (2022). Understanding emotion regulation and humor styles in individuals with callous-unemotional traits and alexithymic traits. The Journal of Psychology, 156(2), 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y. B. (2020). An investigation on the status quo of emotion regulation development in preschool children. Sichuan Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- Zentner, M. (2020). Identifying child temperament risk factors from 2 to 8 years of age: Validation of a brief temperament screening tool in the US, Europe, and China. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(5), 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeytinoglu, S., Calkins, S. D., Swingler, M. M., & Leerkes, E. M. (2017). Pathways from maternal effortful control to child self-regulation: The role of maternal emotional support. Journal of Family Psychology, 31(2), 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N., Liu, W., Che, H., & Fan, X. (2023). Effortful control and depression in school-age children: The chain mediating role of emotion regulation ability and cognitive reappraisal strategy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 327, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Li, K., Zheng, H., & Pasalich, D. S. (2024). Daily associations between parental warmth and discipline and adolescent conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Prevention Science. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Zou, S., & Li, Y. (2024). Relations between maternal parenting styles and callous-unemotional behavior in Chinese children: A longitudinal study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 154, 106865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumbach, J., Rademacher, A., & Koglin, U. (2021). Conceptualizing callous-unemotional traits in preschoolers: Associations with social-emotional competencies and aggressive behavior. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 528 | 48.2 |

| Female | 567 | 51.8 | |

| Place of Residence | Urban | 1022 | 93.3 |

| Rural | 73 | 6.7 | |

| Monthly Income (CNY) | ≤2000 | 154 | 14.1 |

| 2001–4000 | 241 | 22.0 | |

| 4001–7000 | 361 | 33.4 | |

| 7001–10,000 | 193 | 17.6 | |

| ≥10,001 | 141 | 12.9 | |

| Educational Levels | Junior High School and Below | 119 | 10.9 |

| High School and Technical Secondary School | 190 | 17.3 | |

| Junior College | 299 | 27.3 | |

| Undergraduate | 418 | 38.2 | |

| Postgraduate and Above | 69 | 6.3 | |

| Professions | Freelance | 153 | 14.0 |

| Farmers | 15 | 1.4 | |

| Businessmen | 200 | 18.3 | |

| Teacher/Doctor | 177 | 16.2 | |

| Workers | 314 | 28.6 | |

| Officers | 236 | 21.5 |

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child age (month) | 60.56 | 9.52 | — | |||||

| 2. Gender | 0.53 | 0.50 | 0.10 ** | — | ||||

| 3. Parental media soothing | 2.07 | 0.73 | −0.06 * | 0.03 | — | |||

| 4. Emotion regulation | 3.08 | 0.56 | 0.03 | −0.09 ** | −0.17 *** | — | ||

| 5. CU behaviors | 1.90 | 0.36 | −0.06 * | 0.05 | 0.20 *** | −0.45 *** | — | |

| 6. Effortful control | 5.18 | 0.97 | 0.08 * | −0.09 ** | −0.20 *** | 0.51 *** | −0.42 *** | — |

| Emotion Regulation | CU Behaviors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | β | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Parental media soothing | −0.13 | 0.02 | −5.68 ** | [−0.17, −0.08] | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.58 *** | [0.04, 0.09] |

| Emotion regulation | −0.28 | 0.02 | −15.59 *** | [−0.31, −0.24] | ||||

| Age (month) | 0.002 | 0.002 | 1.07 | [−0.002, 0.005] | −0.002 | 0.001 | −1.48 | [−0.004, 0.001] |

| Gender | 0.10 | 0.03 | 3.09 ** | [0.04, 0.17] | −0.006 | 0.02 | −0.33 | [−0.05, 0.03] |

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.22 | ||||||

| F | 14.69 *** | 76.35 *** | ||||||

| Emotion Regulation | CU Behaviors | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | t | 95% CI | β | SE | t | 95% CI | |

| Parental media soothing | −0.05 | 0.02 | −2.69 ** | [−0.09, −0.02] | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.50 *** | [0.03, 0.08] |

| Emotion regulation | −0.20 | 0.02 | −10.51 ** | [−0.24, −0.17] | ||||

| Effortful control | 0.28 | 0.02 | 18.36 *** | [0.248, 0.307] | −0.10 | 0.01 | −8.72 *** | [−0.12, −0.08] |

| Parental media soothing × Effortful control | 0.08 | 0.02 | 4.36 *** | [0.043, 0.114] | ||||

| Emotion regulation × Effortful control | −0.10 | 0.01 | −7.22 *** | [−0.13, −0.07] | ||||

| Age (month) | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.003 | [−0.003, 0.003] | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.68 | [−0.003, 0.001] |

| Gender | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.77 | [−0.006, 0.108] | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.58 | [−0.03, 0.05] |

| R2 | 0.28 | 0.29 | ||||||

| F | 85.83 *** | 75.47 *** | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, R.; Hu, K.; Huang, P.; Cai, L. Does Parental Media Soothing Lead to the Risk of Callous–Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood? Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081082

Tan R, Hu K, Huang P, Cai L. Does Parental Media Soothing Lead to the Risk of Callous–Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood? Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081082

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Ruifeng, Kai Hu, Peishan Huang, and Liman Cai. 2025. "Does Parental Media Soothing Lead to the Risk of Callous–Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood? Testing a Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081082

APA StyleTan, R., Hu, K., Huang, P., & Cai, L. (2025). Does Parental Media Soothing Lead to the Risk of Callous–Unemotional Behaviors in Early Childhood? Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1082. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081082