Intergenerational Parenting Styles and Children’s Problem Behaviors: The Mediating Role of the Grandparent–Parent Relationship

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Current Study

- (a)

- Intergenerational parenting styles can be categorized into distinct latent profiles.

- (b)

- These latent profiles of intergenerational parenting styles have differential impacts on grandchildren’s problem behaviors.

- (c)

- Certain demographic characteristics, such as the number of siblings, the child’s grade level, and the type of grandparent involved, will predict membership in different grandparent–parent parenting profiles.

- (d)

- These parenting profiles are linked to grandchildren’s problem behaviors, with the grandparent–parent relationship mediating this association.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

3.2. Research Tools

3.2.1. Parenting Style

3.2.2. Grandparents’ Parenting Style

3.2.3. Grandchildren’s Problem Behaviors

3.2.4. Grandparent–Parent Relationship

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

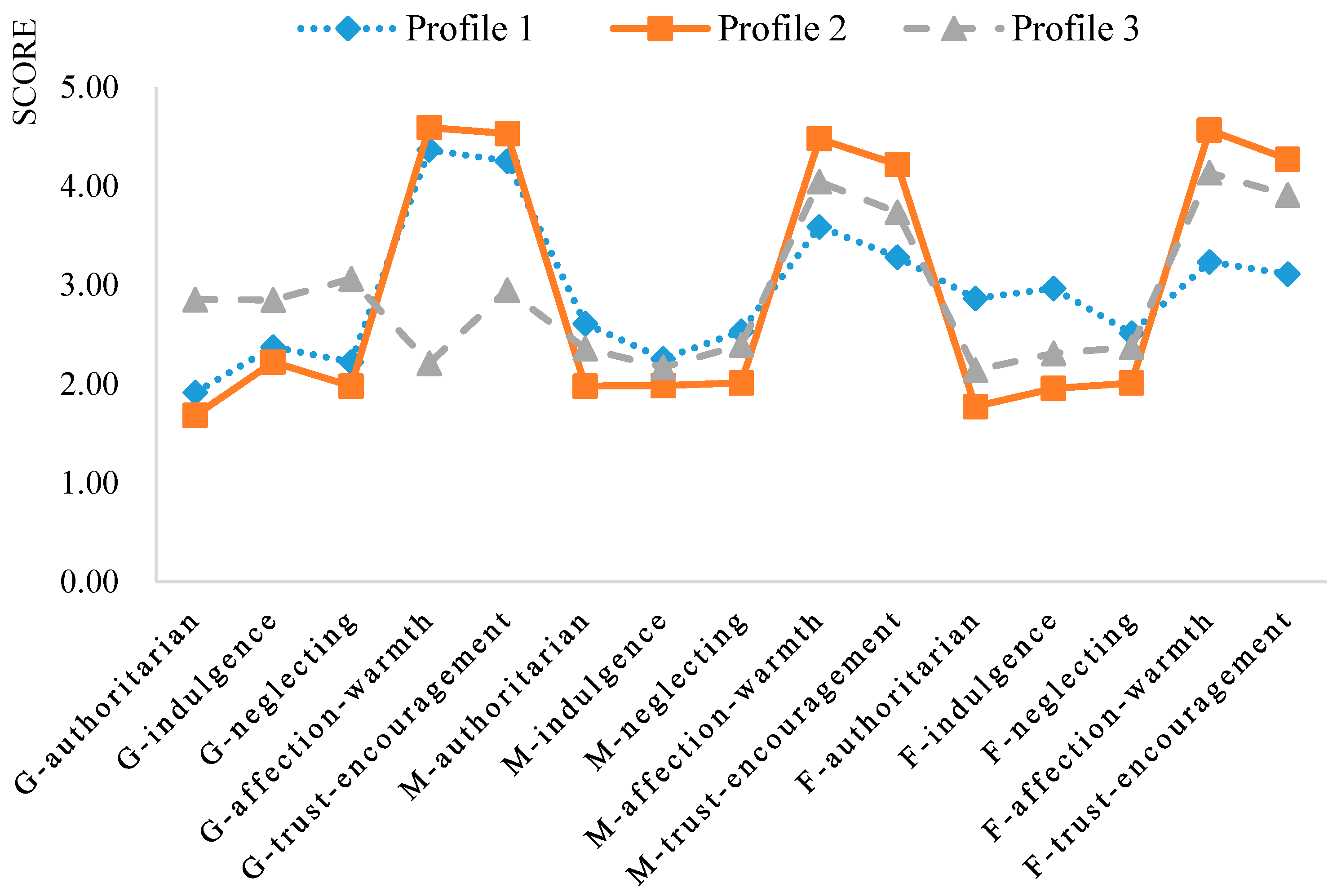

4.1. Latent Profile Analysis Results of Intergenerational Parenting Styles

4.2. Predictors of Latent Profile Membership

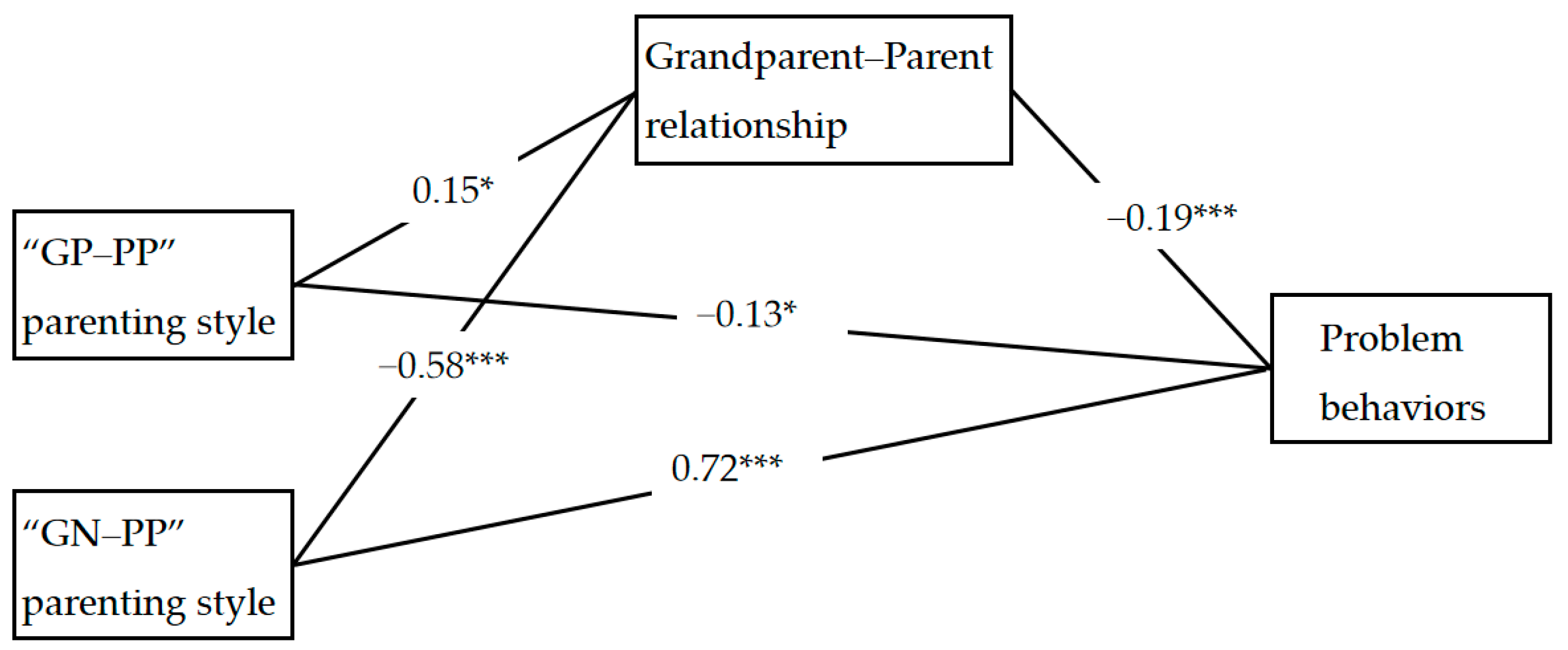

4.3. The Relationship Between Intergenerational Parenting Styles and the Problem Behaviors of Children

5. Discussion

5.1. The Latent Profile Analysis of Intergenerational Parenting Styles

5.2. The Relationship Between Intergenerational Parenting Styles and the Problem Behaviors of Children

5.3. Practical Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Attar-Schwartz, S., Tan, J. P., & Buchanan, A. (2009). Adolescents’ perspectives on relationships with grandparents: The contribution of adolescent, grandparent, and parent–grandparent relationship variables. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aunola, K., & Nurmi, J. E. (2005). The role of parenting styles in children’s problem behavior. Child Development, 76(6), 1144–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belfer, M. L. (2008). Child and adolescent mental disorders: The magnitude of the problem across the globe. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49(3), 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsky, J. (2005). Differential susceptibility to rearing influence: An evolutionary hypothesis and some evidence. In B. Ellis, & D. Bjorklund (Eds.), Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary psychology and child development* (pp. 139–163). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, M. (1978). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J., Chen, M., & Fu, Y. (2025). Harsh versus supportive (grand) parenting practices and child behaviour problems in urban chinese families: Does multigenerational coresidence make a difference? Child & Family Social Work. online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Zhang, Y., & Lu, W. (2020). A review of the influencing factors of parenting styles. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(4), 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chi, L., & Wang, Y. (2002). Theoretical advance on the relations between martal conflict and problem behavors in children. Advances in Psychological Science, 10(4), 411–417. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, L. J., Mirzadegan, I. A., & Meyer, A. (2020). The association between parenting and the error-related negativity across childhood and adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 45, 100852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, C., Umemura, T., Mann, T., Jacobvitz, D., & Hazen, N. (2015). Marital quality over the transition to parenthood as a predictor of coparenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(12), 3636–3651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), 193–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P. T., & Cummings, E. M. (1994). Marital conflict and child adjustment: An emotional security hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 116(3), 387–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derlan, C. L., Umana-Taylor, A. J., Updegraff, K. A., & Jahromi, L. B. (2018). Mother-grandmother and mother-father coparenting across time among Mexican origin adolescent mothers and their families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(2), 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C., Niu, H., & Wang, M. (2019). Parental corporal punishment and children’s problem behaviors: The moderating effects of parental inductive reasoning in China. Children and Youth Services Review, 99, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F., Bai, X. J., Zhang, P., & Cao, H. B. (2023). A meta-analysis of the relationship between parenting styles and suicidal ideation in chinese adolescents. Psychological Development and Education, 39(1), 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, W., & Adesman, A. (2017). Grandparents raising grandchildren: A primer for pediatricians. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 29(3), 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, M. W., Fairchild, A. J., Mark Cummings, E., & Davies, P. T. (2014). Marital conflict in early childhood and adolescent disordered eating: Emotional insecurity about the marital relationship as an explanatory mechanism. Eating Behaviors, 15(4), 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, K., Price, D., Di Gessa, G., Ribe, E., Stuchbury, R., & Tinker, A. (2013). Grandparenting in Europe: Family policy and grandparents’ role in providing childcare. Grandparents Plus. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, E. C. L., & Kuczynski, L. (2009). Agency and power of single children in multi-generational families in urban Xiamen, China. Culture, 15(4), 506–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y. (2005). An exploratory design of the questionnaire of parenting style [Doctoral dissertation, Southwest University]. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, A., Lamping, D. L., & Ploubidis, G. B. (2010). When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 38(5), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C. H., Newell, L. D., & Olsen, S. F. (2003). Parenting skills and social-communicative competence in childhood. In J. O. Greene, & B. R. Burleson (Eds.), Handbook of communication and social interaction skills (pp. 753–797). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y., Liu, C., & Luo, R. (2023). Emotional warmth and rejection parenting styles of grandparents/great grandparents and the social–emotional development of grandchildren/great grandchildren. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(2), 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hipp, J. R., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychological Methods, 11(1), 36–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoang, N. T., & Kirby, J. N. (2020). A meta-ethnography synthesis of joint care practices between parents and grandparents from Asian cultural backgrounds: Benefits and challenges. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, H. J. (2015). Educational differences in the cognitive functioning of grandmothers caring for grandchildren in South Korea. Research on Aging, 37(5), 500–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jun, H. J., Cho, K., Park, M., Han, S., & Wassel, J. (2013). Longitudinal study of the effect of the transition to a grandparenting role on depression and life-satisfaction. Journal of the Korean Gerontological Society, 33, 515–536. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, T., & Wickrama, A. S. (2008). An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, P. C., & Hank, K. (2014). Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China and Korea: Findings from CHARLS and KLoSA. Journal of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(4), 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, R. M., Mark, K. M., & Oliver, B. R. (2018). Coparenting and children’s disruptive behavior: Interacting processes for parenting sense of competence. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(1), 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., & Park, S. H. (2017). Interplay between attachment to peers and parents in Korean adolescents’ behavior problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(1), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M. (2002). Concepts and theories of human development (5th ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Leung, C., & Fung, B. (2014). Non-custodial grandparent caregiving in Chinese families: Implications for family dynamics. Journal of Children’s Services, 9, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Zhou, S., & Guo, Y. (2020). Bidirectional longitudinal relations between parent-grandparent co-parenting relationships and chinese children’s effortful control during early childhood. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Cui, N., Cao, F., & Liu, J. (2016). Children’s bonding with parents and grandparents and its associated factors. Child Indicators Research, 9(2), 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Cui, N., Kok, H. T., Deatrick, J., & Liu, J. (2019). The relationship between parenting styles practiced by grandparents and children’s emotional and behavioral problems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1899–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S. A. (2018). The effect of marital conflict between father and mother on their children’s problem behaviors: Mediating effect of children’s attachment security. The Korea Association of Child Care and Education, 113, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X., Zhang, Y., Liao, Y., & Xie, W. (2023). Socioeconomic status and problem behaviors in young chinese children: A moderated mediation model of parenting styles and only children. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1029408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, H., Zhang, S. F., Hua, S. W., Li, H. B., Wang, H. H., Yue, L. H., Zhang, M. L., & Zhang, J. R. (2023). The influence of grandparents-parents co-parenting relationships on self-supporting behavior of children aged 6~12: The moderating effect of birth order. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(4), 989–993. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J., & Wuerker, A. (2005). Biosocial bases of aggressive and violent behavior—Implications for nursing studies. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42(2), 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X., Xing, X., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Executive function and peer relations: The mediating role of externalizing problem behavior. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26(3), 546–550+527. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y., Qi, M., Huntsinger, C. S., & Zhang, Q. (2020). Grandparent involvement and preschoolers’ social adjustment in Chinese three-generation families: Examining moderating and mediating effects. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhi, D., Demou, E., & Niedzwiedz, C. (2024). Mental health and behavioral interventions for children and adolescents with incarcerated parents: A systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 33(2), 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X. X., & Du, B. F. (2023). Relation of psychological behavioral problems to peer quality and bullying experiences in children from difficult families. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 37(3), 206–212. [Google Scholar]

- Muhtadie, L., Zhou, Q., Eisenberg, N., & Wang, Y. (2013). Predicting internalizing problems in Chinese children: The unique and interactive effects of parenting and child temperament. Development and Psychopathology, 25(3), 653–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, J. W., Olino, T. M., Roberts, R. E., Seeley, J. R., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (2008). Intergenerational transmission of internalizing problems: Effects of parental and grandparental major depressive disorder on child behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roza, S. J., Hofstra, M. B., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2003). Stable prediction of mood and anxiety disorders based on behavioral and emotional problems in childhood: A 14-year follow-up during childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(12), 2116–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safdar, S., & Zahrah, S. M. (2016). Impact of parenting styles on the intensity of parental and peer attachment: Exploring the gender differences in adolescents. American Journal of Applied Psychology, 4(2), 23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sahota, N., Shott, M. E., & Frank, G. K. W. (2024). Parental styles are associated with eating disorder symptoms, anxiety, interpersonal difficulties, and nucleus accumbens response. Eating and Weight Disorders—Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 29(1), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M. R., Kirby, J. N., Tellegen, C. L., & Day, J. J. (2014). The triple p–positive parenting program: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(4), 337–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sear, R., Mace, R., & McGregor, I. A. (2000). Maternal grandmothers improve nutritional status and survival of children in rural Gambia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Science, 267(1453), 1641–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, N., & Yang, F. (2021). Grandparenting and children’s health-empirical evidence from China. Child Indicators Research, 14, 1105–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaniecki, E., & Barnes, J. (2016). Measurement issues: Measures of infant mental health. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 21(1), 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanskanen, A. O., Helle, S., & Danielsbacka, M. (2023). Differential grandparental investment when maternal grandmothers are living versus deceased. Biology Letters, 19(5), 20230061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teague, S. J., Newman, L. K., Tonge, B. J., Gray, K. M., & Team, M. (2020). Attachment and child behaviour and emotional problems in autism spectrum disorder with intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(3), 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, R. E., Nagin, D. S., Seguin, J. R., Zoccolillo, M., Zelazo, P. D., Boivin, M., & Japel, C. (2004). Physical aggression during early childhood: Trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics, 114(1), e43–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, M. M., Berry, O. O., Warner, V., Gameroff, M. J., Skipper, J., Talati, A., & Wickramaratne, P. (2016). A 30-year study of 3 generations at high risk and low risk for depression. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(9), 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Xiao, B., Zhu, L., & Li, Y. (2022). The influence of parent-grandparent co-parenting on children’s problem behaviors and its potential mechanisms. Early Education and Development, 34(4), 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C. (2020). The characteristics of family relationships and its influence on grandchildren’s prosocial behavior under the mode of intergenerational rearing [Doctoral dissertation, Shanxi University]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T., Zhou, X., Liang, L., Yuan, K., & Bian, Y. (2025). Relationship between parent-adolescent discrepancies in perceived parentalwarmth and children’s depressive symptoms and aggressive behavior. Psychological Development and Education, 41(6), 869–880. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D., Hou, J., Jiang, L., & Chen, Z. (2017). Tracking study of the bidirectional effects of parenting style and externalizing behavior. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition), 43(6), 106–111. [Google Scholar]

| Profiles | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | pLMRT | pBLRT | Proportions Min (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 283,391.49 | 284,055.11 | 283,654.85 | - | - | - | |

| 2 | 275,740.22 | 276,740.91 | 276,137.35 | 0.92 | 0.751 | <0.001 | 37.53 |

| 3 | 271,138.59 | 272,476.36 | 271,669.49 | 0.96 | 0.242 | <0.001 | 18.78 |

| 4 | 268,391.47 | 270,066.32 | 269,056.14 | 0.96 | 0.188 | <0.001 | 10.38 |

| 5 | 266,432.77 | 268,444.70 | 267,231.21 | 0.96 | 0.584 | <0.001 | 4.34 |

| Profile 1 (n = 263) | Profile 2 (n = 847) | Profile 3 (n = 322) | F | LSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grandparent | Authoritarian | 1.91 ± 0.64 | 1.69 ± 0.53 | 2.85 ± 0.64 | 477.86 *** | 3 > 1 > 2 |

| Indulgence | 2.38 ± 0.75 | 2.22 ± 0.71 | 2.85 ± 0.75 | 85.60 *** | 3 > 1 > 2 | |

| Neglecting | 2.23 ± 0.72 | 1.98 ± 0.62 | 3.07 ± 0.79 | 299.75 *** | 3 > 1 > 2 | |

| Affection-warmth | 4.37 ± 0.63 | 4.59 ± 0.51 | 2.95 ± 0.95 | 747.16 *** | 2 > 1 > 3 | |

| Trust-encouragement | 4.26 ± 0.61 | 4.53 ± 0.50 | 2.95 ± 0.80 | 823.75 *** | 2 > 1 > 3 | |

| Mother | Authoritarian | 2.61 ± 0.78 | 1.98 ± 0.55 | 2.36 ± 0.74 | 111.52 *** | 1 > 3 > 2 |

| Indulgence | 2.26 ± 0.89 | 1.98 ± 0.67 | 2.17 ± 0.77 | 17.64 *** | 1 = 3 > 2 | |

| Neglecting | 2.54 ± 0.79 | 2.01 ± 0.61 | 2.40 ± 0.75 | 79.31 *** | 1 > 3 > 2 | |

| Affection-warmth | 3.58 ± 0.88 | 4.48 ± 0.67 | 4.04 ± 0.82 | 158.14 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 | |

| Trust-encouragement | 3.27 ± 0.96 | 4.22 ± 0.65 | 3.72 ± 0.80 | 177.07 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 | |

| Father | Authoritarian | 2.87 ± 0.50 | 1.78 ± 0.52 | 2.14 ± 0.68 | 389.44 *** | 1 > 3 > 2 |

| Indulgence | 2.98 ± 0.79 | 1.96 ± 0.63 | 2.31 ± 0.75 | 221.21 *** | 1 > 3 > 2 | |

| Neglecting | 2.70 ± 0.66 | 2.02 ± 0.64 | 2.37 ± 0.73 | 114.69 *** | 1 > 3 > 2 | |

| Affection-warmth | 3.23 ± 0.93 | 4.57 ± 0.49 | 4.12 ± 0.87 | 392.79 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 | |

| Trust-encouragement | 3.10 ± 0.66 | 4.27 ± 0.57 | 3.90 ± 0.76 | 346.54 *** | 2 > 3 > 1 |

| “GP-PN” Profile | “GP-PP” Profile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | ||

| Sibling number | Non-only-child | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Only-child | 0.85 | [0.53, 1.63] | 0.39 *** | [0.27, 0.57] | |

| Grade | Primary school | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Junior middle school | 1.91 *** | [1.25, 2.97] | 2.25 *** | [1.87, 3.76] | |

| Grandparent’s type | Maternal grandfather | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Paternal grandmother | 1.15 | [0.55, 2.43] | 1.09 | [0.59, 2.05] | |

| Paternal grandfather | 1.29 | [0.59, 2.79] | 1.38 | [0.72, 2.64] | |

| Maternal grandmother | 2.84 ** | [1.33, 6.08] | 2.20 * | [1.18, 4.11] | |

| Problem Behaviors (M ± SD) | F | LSD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intergenerational parenting styles | “GP-PN” parenting style (n = 263) | 11.60 ± 5.14 | 135.49 *** | “GN-PP” parenting style > “GP-PN” parenting style > “GP-PP” parenting style |

| “GP-PP” parenting style (n = 847) | 10.74 ± 4.83 | |||

| “GN-PP” parenting style (n = 322) | 16.18 ± 5.62 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. “GP-PN” parenting style | 1 | — | — | — | — |

| 2. “GP-PP” parenting style | −0.57 *** | 1 | — | — | — |

| 3. “GN-PP” parenting style | −0.26 *** | −0.65 *** | 1 | — | — |

| 4. Problem behaviors | −0.05 | −0.30 *** | 0.40 *** | 1 | — |

| 5. Grandparent–parent relationship | 0.02 | 0.23 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.29 *** | 1 |

| M | 0.18 | 0.59 | 0.22 | 12.12 | 27.44 |

| SD | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.42 | 5.53 | 3.87 |

| Mediation Pathway | Effect | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LLCI | ULCI | |||

| “GP–PP” parenting style → Grandparent–parent relationship → Problem behaviors | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.06 | −0.003 |

| “GN–PP” parenting style → Grandparent–parent relationship → Problem behaviors | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, F.; Zhang, F.; Lyu, R.; Wu, X.; Wang, Y. Intergenerational Parenting Styles and Children’s Problem Behaviors: The Mediating Role of the Grandparent–Parent Relationship. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081029

Lu F, Zhang F, Lyu R, Wu X, Wang Y. Intergenerational Parenting Styles and Children’s Problem Behaviors: The Mediating Role of the Grandparent–Parent Relationship. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081029

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Furong, Feixia Zhang, Rong Lyu, Xinru Wu, and Yuyu Wang. 2025. "Intergenerational Parenting Styles and Children’s Problem Behaviors: The Mediating Role of the Grandparent–Parent Relationship" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081029

APA StyleLu, F., Zhang, F., Lyu, R., Wu, X., & Wang, Y. (2025). Intergenerational Parenting Styles and Children’s Problem Behaviors: The Mediating Role of the Grandparent–Parent Relationship. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1029. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081029