Suicide Prevention Measures at High-Risk Locations: A Goal-Directed Motivation Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Goal Pursuit & Suicide

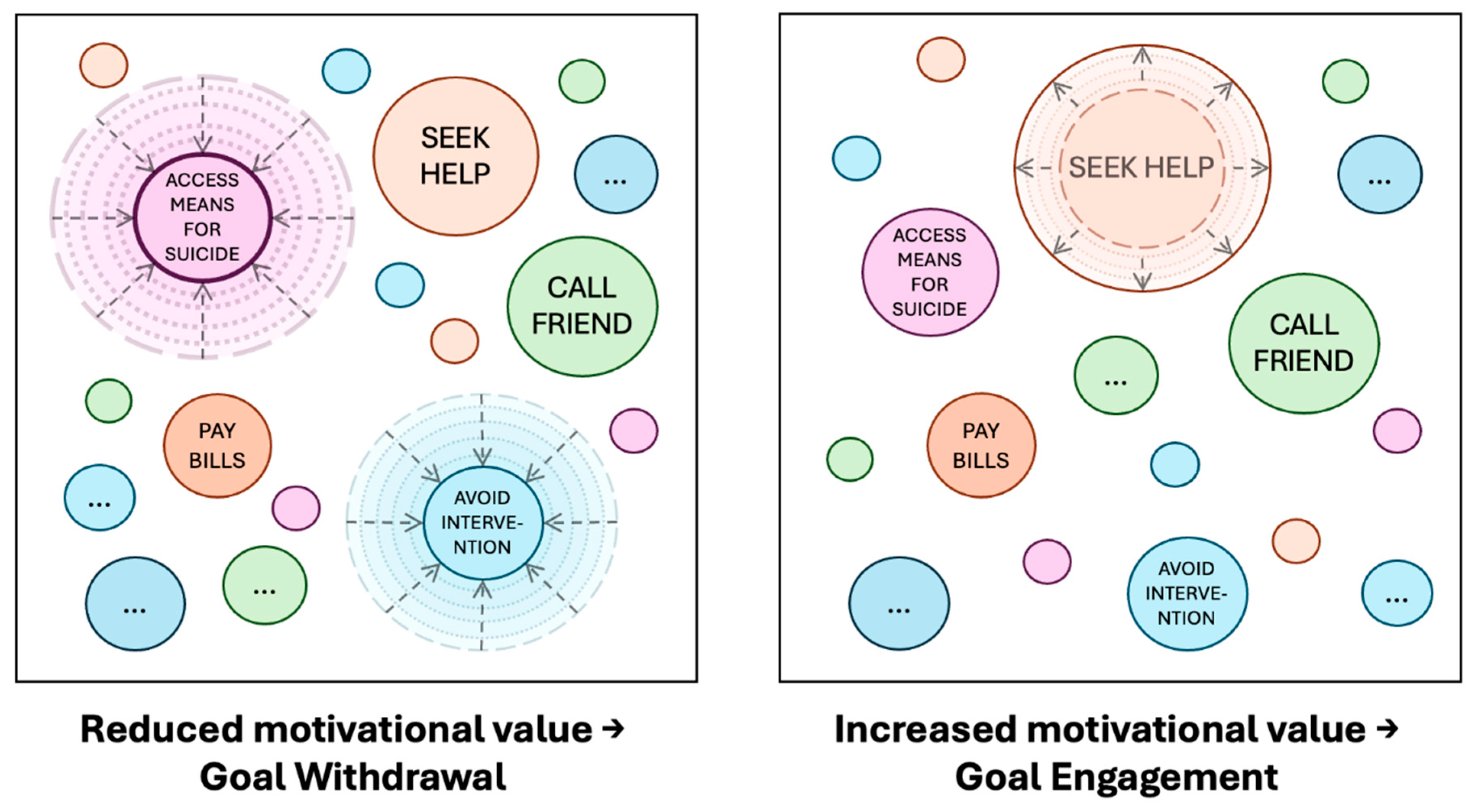

Goal Prioritisation

2. Restricting Access to Means for Suicide

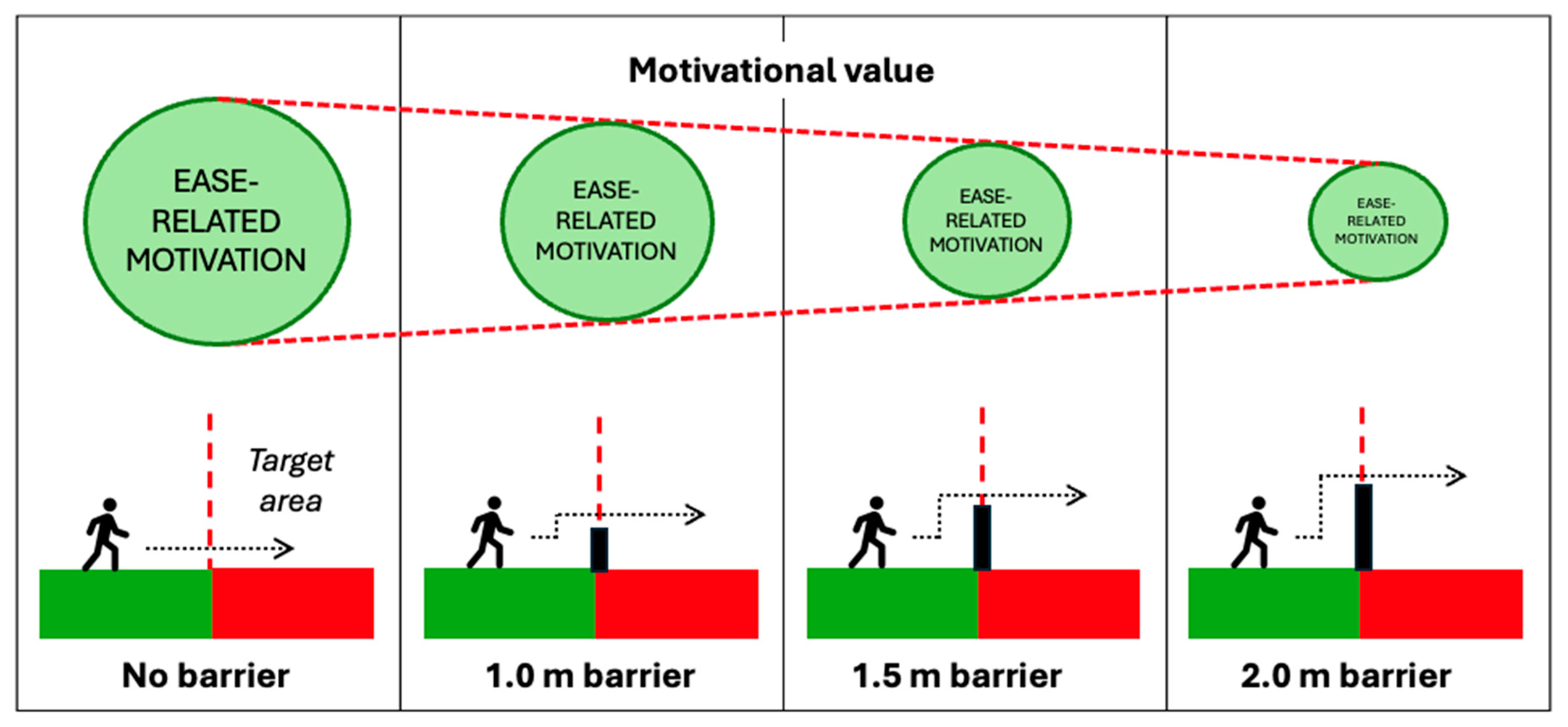

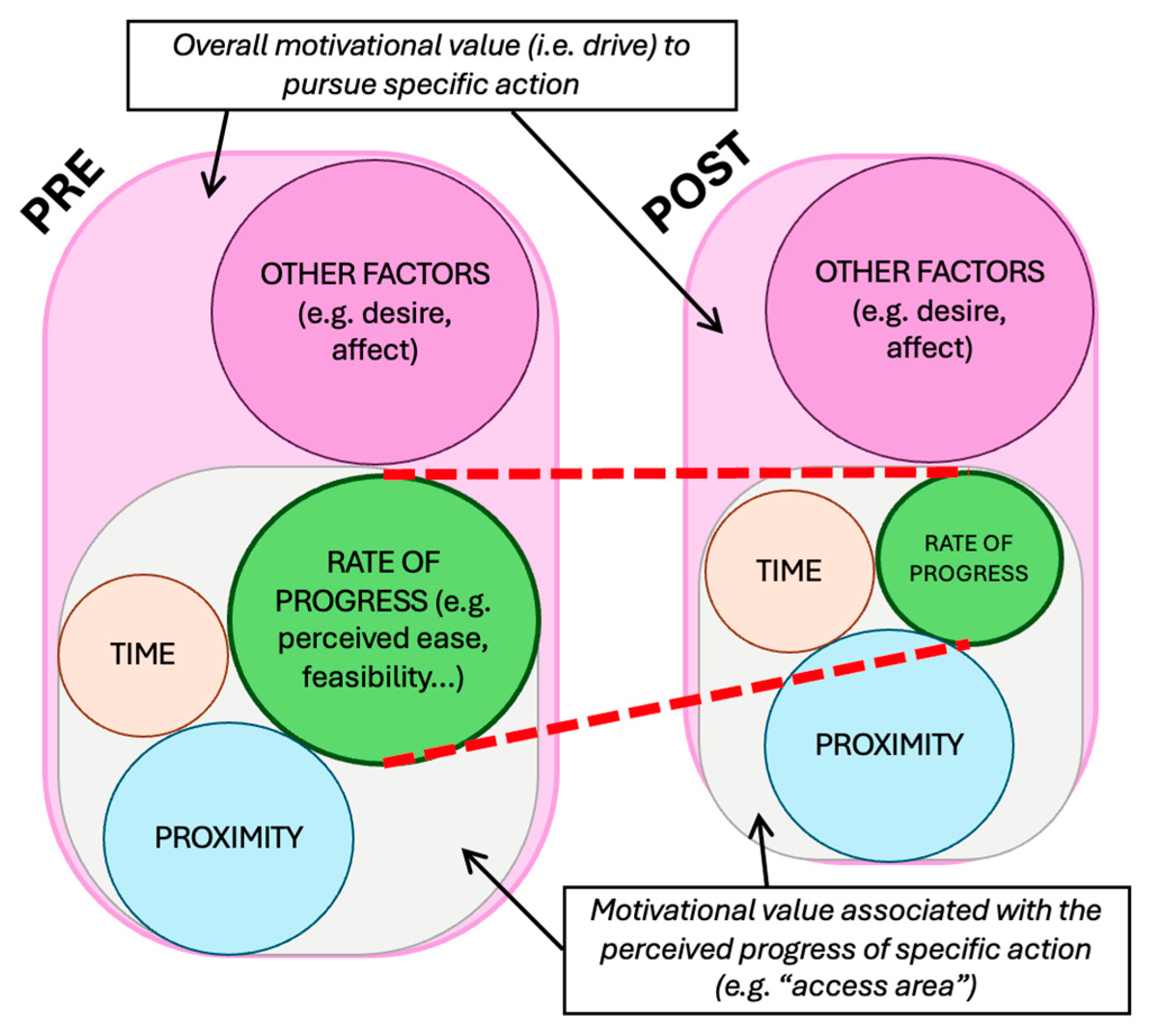

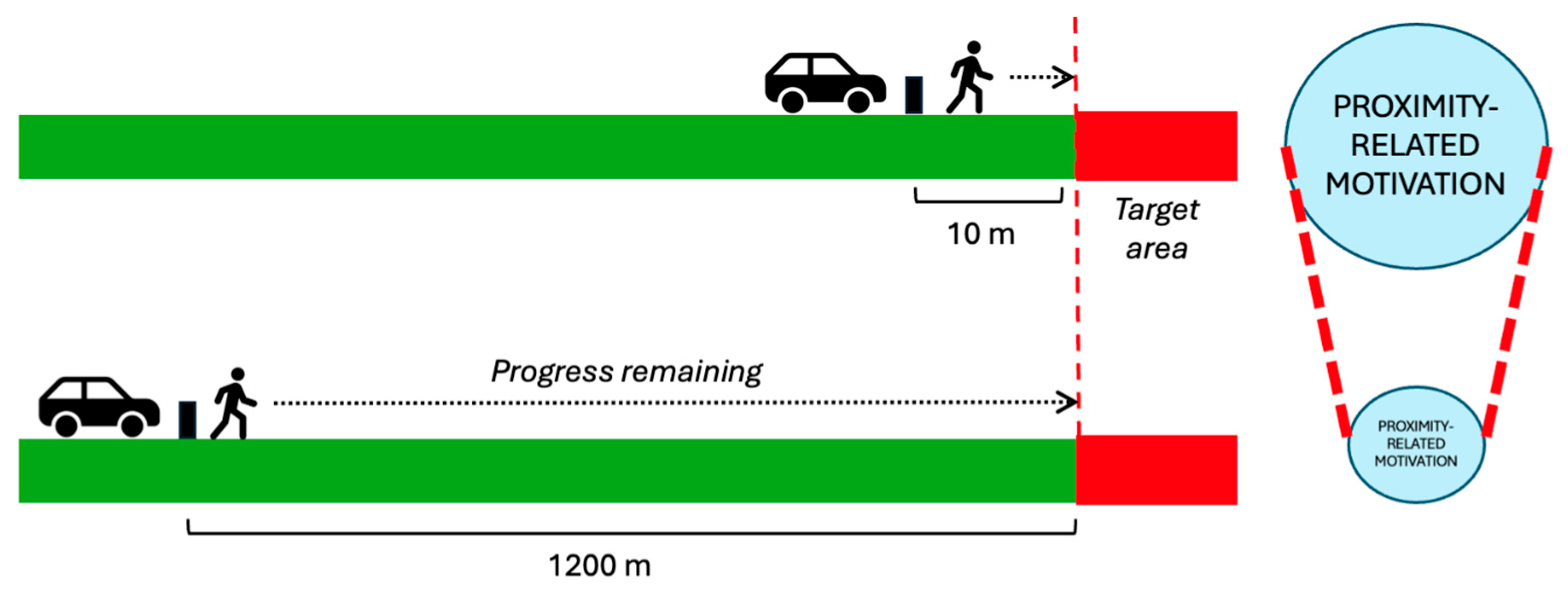

2.1. Rate-of-Progress Gradient

2.1.1. Environmental Changes to Decrease Ease of Access

2.1.2. Integrating Person-Level Factors

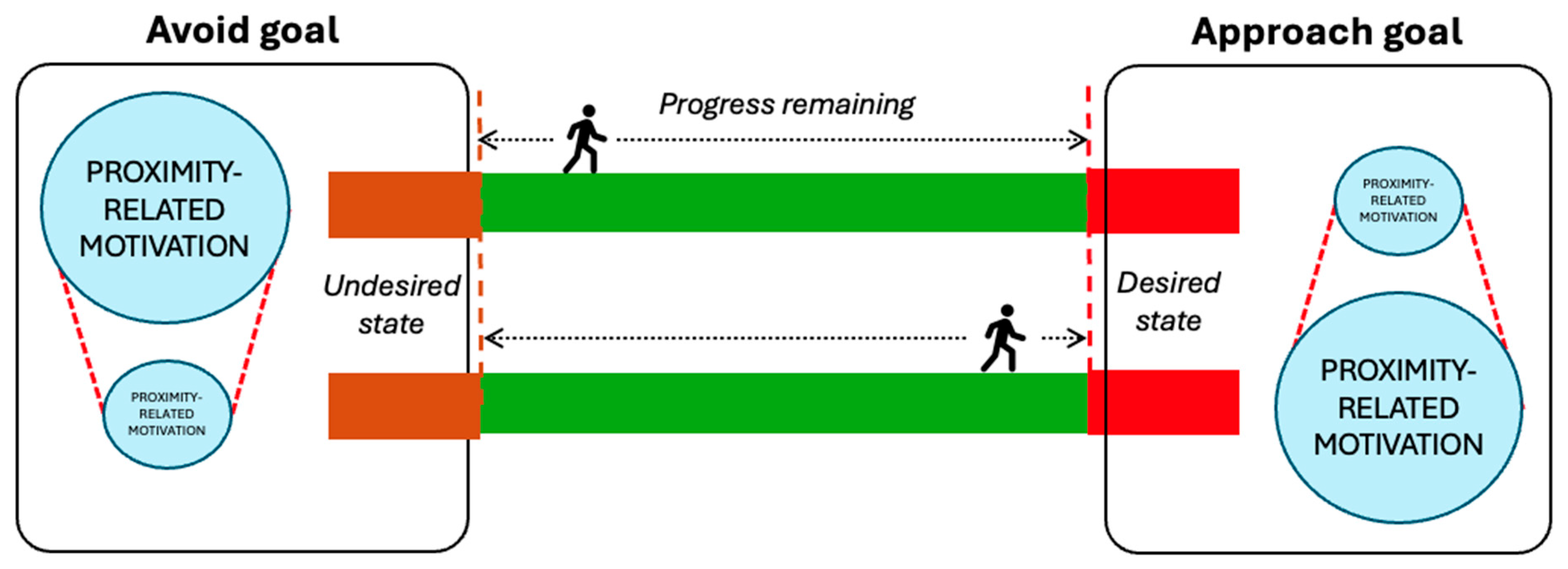

2.2. Distance Gradient

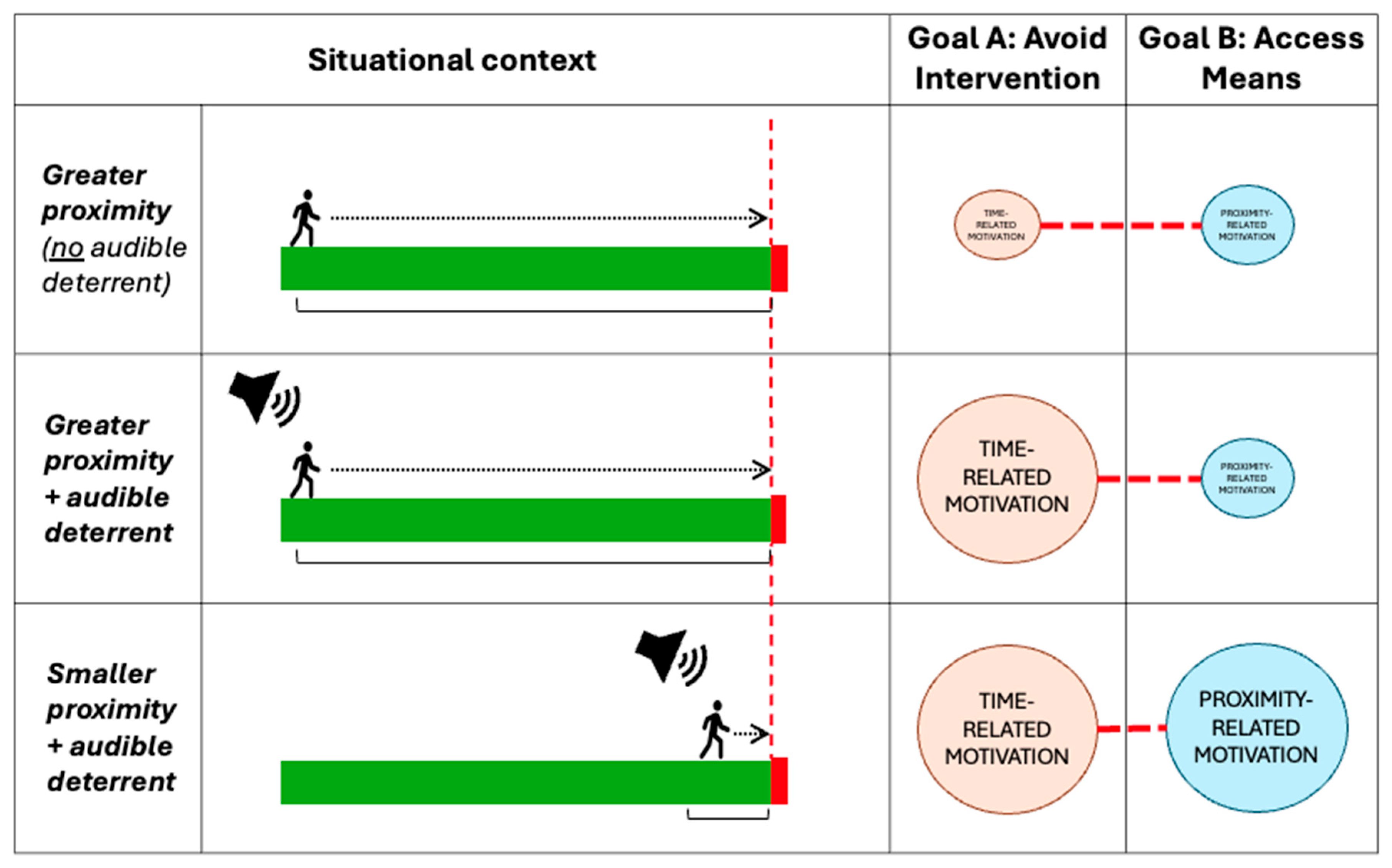

2.2.1. Placement of Intervention

2.2.2. Gaps in Coverage

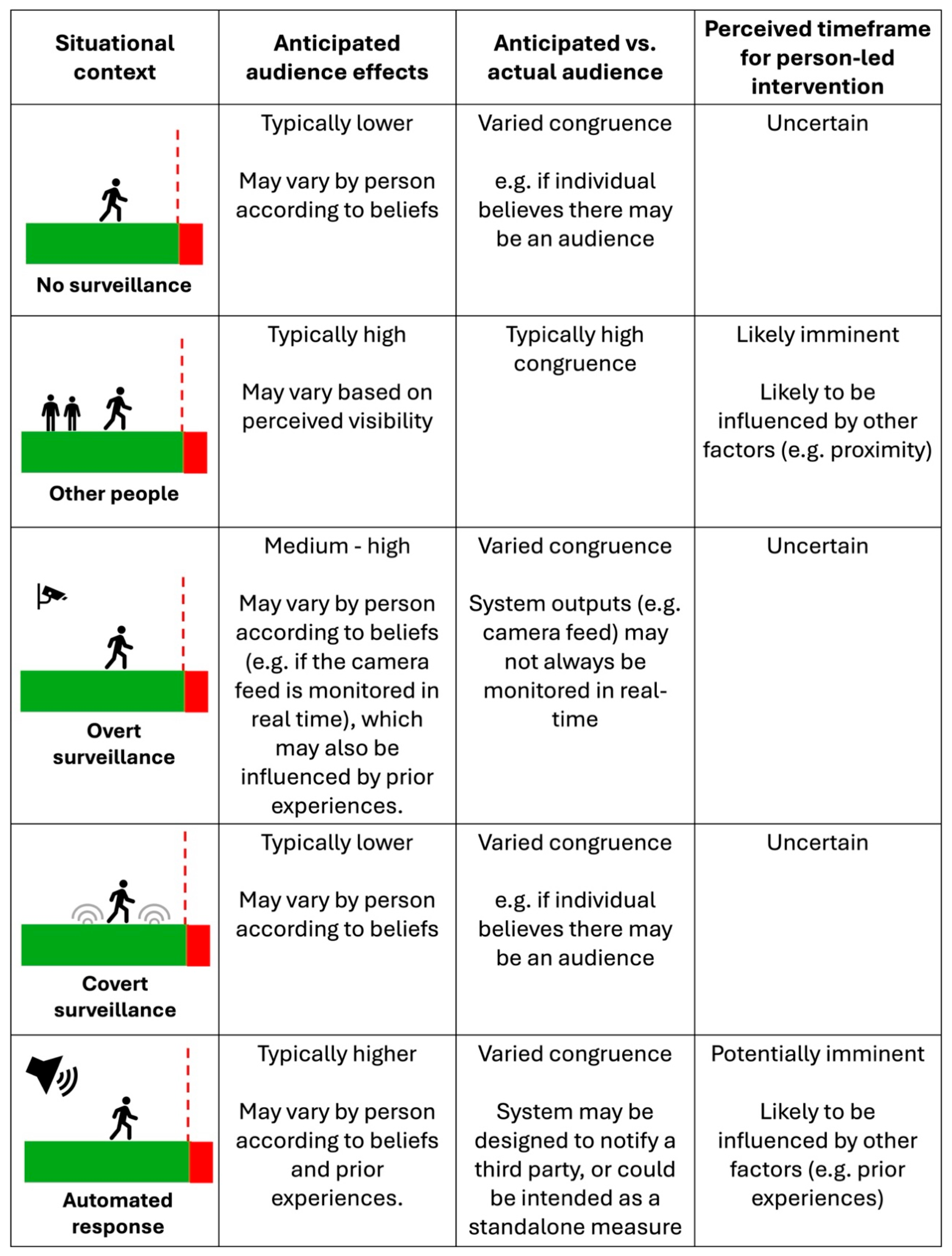

3. Increasing Likelihood of Third-Party Intervention

3.1. Presence of Others and Visibility

3.1.1. Lighting-Based Interventions

3.1.2. Presence of Surveillance Technologies

3.1.3. Use of Automated Audible and Visual Deterrents

3.2. Drawing Attention to Atypical Behaviours

4. Help-Seeking

4.1. Help-Seeking as an Alternative and/or Additional Goal

4.1.1. Goal Shielding

4.1.2. “Bursting the Bubble”

4.2. Contextualising Help-Seeking at a High-Risk Location

Effectiveness of Help-Seeking Measures from a Goal-Pursuit Perspective

5. Discussion

Limitations and Opportunities

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alister, M., Herbert, S. L., Sewell, D. K., Neal, A., & Ballard, T. (2024). The impact of cognitive resource constraints on goal prioritization. Cognitive Psychology, 148, 101618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Motivation. In APA dictionary of psychology. American Psychological Association. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/motivation (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Armstrong, L. L., & Manion, I. G. (2006). Suicidal ideation in young males living in rural communities: Distance from school as a risk factor, youth engagement as a protective factor. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 1(1), 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, T., Neal, A., Farrell, S., Lloyd, E., Lim, J., & Heathcote, A. (2022). A general architecture for modeling the dynamics of goal-directed motivation and decision-making. Psychological Review, 129(1), 146–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, R., Rehm, J., de Oliveira, C., Gozdyra, P., Chen, S., & Kurdyak, P. (2023). The relationship between rurality, travel time to care and death by suicide. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baston, R. (2024). What underlies death/suicide implicit association test measures and how it contributes to suicidal action. Philosophical Psychology, 37(5), 993–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beautrais, A. L. (2001). Effectiveness of barriers at suicide jumping sites: A case study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35(5), 557–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beautrais, A. L., Gibb, S. J., Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., & Larkin, G. L. (2009). Removing bridge barriers stimulates suicides: An unfortunate natural experiment. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(6), 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaven, C. M., & Ekström, J. (2013). A comparison of blue light and caffeine effects on cognitive function and alertness in humans. PLoS ONE, 8(10), e76707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennewith, O., Nowers, M., & Gunnell, D. (2007). Effect of barriers on the Clifton suspension bridge, England, on local patterns of suicide: Implications for prevention. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(3), 266–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennewith, O., Nowers, M., & Gunnell, D. (2011). Suicidal behaviour and suicide from the Clifton Suspension Bridge, Bristol and surrounding area in the UK: 1994–2003. European Journal of Public Health, 21(2), 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhardt, J.-M., Rådbo, H., Silla, A., & Paran, F. (2014). A model of suicide and trespassing processes to support the analysis and decision related to preventing railway suicides and trespassing accidents at railways. In Transport research arena (TRA) 2014 proceedings. Transportation Research Board. [Google Scholar]

- Burnette, C., Ramchand, R., & Ayer, L. (2015). Gatekeeper training for suicide prevention. Rand Health Quarterly, 5(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chellappa, S. L., Steiner, R., Blattner, P., Oelhafen, P., Götz, T., & Cajochen, C. (2011). Non-visual effects of light on melatonin, alertness and cognitive performance: Can blue-enriched light keep us alert? PLoS ONE, 6(1), e16429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, Y. W., Kang, S. J., Matsubayashi, T., Sawada, Y., & Ueda, M. (2016). The effectiveness of platform screen doors for the prevention of subway suicides in South Korea. Journal of Affective Disorders, 194, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapperton, A., Dwyer, J., Spittal, M., & Pirkis, J. (2023). The effectiveness of installing trackside fencing in preventing railway suicides: A pre-post study design in Victoria, Australia. Injury Prevention, 29(6), 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clapperton, A., Dwyer, J., Spittal, M. J., Roberts, L., & Pirkis, J. (2022). Preventing railway suicides through level crossing removal: A multiple-arm pre-post study design in Victoria, Australia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(11), 2261–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, M., Baron, W., & Carroll, A. A. (2006). Highway-railroad grade crossing safety research: Railroad infrastructure trespassing detection systems research in Pittsford, New York (Report No. DOT-VNTSC-FRA-05-07). U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/8901 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Devlin, H. C., Johnson, S. L., & Gruber, J. (2015). Feeling good and taking a chance? Associations of hypomania risk with cognitive and behavioral risk taking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 39(4), 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R., Taylor, P., Wickham, S., & Hutton, P. (2016). Psychosis, delusions and the “jumping to conclusions” reasoning bias: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 42(3), 652–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duthie, G., Reavley, N., Wright, J., & Morgan, A. (2024). The impact of media-based mental health campaigns on male help-seeking: A systematic review. Health Promotion International, 39(4), daae104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J., Spittal, M. J., Scurrah, K., Pirkis, J., Bugeja, L., & Clapperton, A. (2023). Structural intervention at one bridge decreases the overall jumping suicide rate in Victoria, Australia. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 32, e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlangsen, A., la Cour, N., Larsen, C. Ø., Karlsen, S. S., Witting, S., Ranning, A., Wang, A. G., Ørnebjerg, K., Schou, B., & Nordentoft, M. (2023). Efforts to prevent railway suicides in Denmark. Crisis, 44(2), 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J. S. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredin-Knutzén, J., Hadlaczky, G., Andersson, A.-L., & Sokolowski, M. (2022). A pilot study evaluating the effectiveness of preventing railway suicides by mid-track fencing, which restrict easy access to high-speed train tracks. Journal of Safety Research, 83, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredin-Knutzén, J., Hadlaczky, G., Wigren, A., & Sokolowski, M. (2024). A pilot study evaluating the preventive effects of platform-end lengthwise fencing on trespassing, person struck by train and traffic delays. Journal of Safety Research, 88, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabree, S. H., Hiltunen, D., & Ranalli, E. (2019). Railroad implemented countermeasures to prevent suicide: Review of public information (Report No. DOT/FRA/ORD-19/04). U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration. Available online: https://rosap.ntl.bts.gov/view/dot/39205 (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Gair, S. (2008). The psychic disequilibrium of adoption: Stories exploring links between adoption and suicidal thoughts and actions. Australian E-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 7(3), 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerling, I., Roberts, R. M., & Sved Williams, A. (2019). Impact of infant crying on mothers with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder: A qualitative study. Infant Mental Health Journal: Infancy and Early Childhood, 40(3), 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giupponi, G., Thoma, H., Lamis, D., Forte, A., Pompili, M., & Kapfhammer, H. P. (2019). Posttraumatic stress reactions of underground drivers after suicides by jumping to arriving trains; feasibility of an early stepped care outpatient intervention. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 20(5), 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gujral, K., Van Campen, J., Jacobs, J., Kimerling, R., Blonigen, D., & Zulman, D. M. (2022). Mental health service use, suicide behavior, and emergency department visits among rural us veterans who received video-enabled tablets during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 5(4), e226250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, B. N. M., Sawatzky, A., Harper, S. L., O’Sullivan, T. L., & Jones-Bitton, A. (2022). “Farmers aren’t into the emotions and things, right?”: A qualitative exploration of motivations and barriers for mental health help-seeking among Canadian farmers. Journal of Agromedicine, 27(2), 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, A. F. d. C., & Lind, F. (2016). Audience effects: What can they tell us about social neuroscience, theory of mind and autism? Culture and Brain, 4(2), 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon-Jones, E., Gable, P., & Price, T. F. (2012). The influence of affective states varying in motivational intensity on cognitive scope. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawton, K., Townsend, E., Deeks, J., Appleby, L., Gunnell, D., Bennewith, O., & Cooper, J. (2001). Effects of legislation restricting pack sizes of paracetamol and salicylate on self poisoning in the United Kingdom: Before and after study. BMJ, 322(7296), 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heesen, K., Mérelle, S., van den Brand, I., van Bergen, D., Baden, D., Slotema, K., Gilissen, R., & van Veen, S. (2024). The forever decision: A qualitative study among survivors of a suicide attempt. eClinicalMedicine, 69, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinig, I., Wittchen, H.-U., & Knappe, S. (2021). Help-seeking behavior and treatment barriers in anxiety disorders: Results from a representative German community survey. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(8), 1505–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmer, A., Meier, P., & Reisch, T. (2017). Comparing different suicide prevention measures at bridges and buildings: Lessons we have learned from a national survey in Switzerland. PLoS ONE, 12(1), e0169625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henson, K. E., Brock, R., Charnock, J., Wickramasinghe, B., Will, O., & Pitman, A. (2019). Risk of suicide after cancer diagnosis in England. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(1), 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, W., & Van Dillen, L. (2012). Desire: The new hot spot in self-control research. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdaway, S., Evans, E., & Webb, S. (2012). Improving suicide prevention measures on the rail network in Great Britain. Literature review (No. T845). Rail Safety Standards and Board. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, N. R., Botelho, E., Wolford-Clevenger, C., & Clark, K. A. (2024). Previous mental health care and help-seeking experiences: Perspectives from sexual and gender minority survivors of near-fatal suicide attempts. Psychological Services, 21(1), 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ichikawa, M., Inada, H., & Kumeji, M. (2014). Reconsidering the effects of blue-light installation for prevention of railway suicides. Journal of Affective Disorders, 152–154, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaac, M., & Bennett, J. (2005). Prevention of suicide by jumping: The impact of restriction of access at Beachy Head, Sussex during the foot and mouth crisis 2001. Public Health Medicine, 6(1), 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Joyner, L., Cliffe, B., Mackenzie, J. M., Pettersen, E., Marsh, I., Phillips, P., & Marzano, L. (2024). The use of smart surveillance technologies for suicide prevention in public spaces: A professional stakeholder survey from the United Kingdom. Research Square. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallberg, V.-P., & Silla, A. (2017). Prevention of railway trespassing by automatic sound warning—A pilot study. Traffic Injury Prevention, 18(3), 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, L. K., Rousaki, A., Joyner, L. C., Barrett, L. A. F., & Orchard, L. J. (2022). The online behaviour taxonomy: A conceptual framework to understand behaviour in computer-mediated communication. Computers in Human Behavior, 137, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopetz, C., & Orehek, E. (2015). When the end justifies the means: Self-defeating behaviors as “rational” and “successful” self-regulation. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(5), 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopetz, C., Woerner, J. I., & Briskin, J. L. (2018). Another look at impulsivity: Could impulsive behavior be strategic? Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(5), e12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kube, T., & Rozenkrantz, L. (2021). When beliefs face reality: An integrative review of belief updating in mental health and illness. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 247–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupfer, T. R., Wyles, K. J., Watson, F., La Ragione, R. M., Chambers, M. A., & Macdonald, A. S. (2019). Determinants of hand hygiene behaviour based on the theory of interpersonal behaviour. Journal of Infection Prevention, 20(5), 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y. Y., Huang, X.-Y., Chen, C.-Y., & Shao, W.-C. (2009). The lived experiences of brokered brides who have attempted suicide in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(24), 3409–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, J. M., Borrill, J., Hawkins, E., Fields, B., Kruger, I., Noonan, I., & Marzano, L. (2018). Behaviours preceding suicides at railway and underground locations: A multimethodological qualitative approach. BMJ Open, 8(4), e021076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackenzie, J. M., Marsh, I., Fields, B., Kruger, I., Katsampa, D., Crivatu, I., & Marzano, L. (2025). Preventing suicides on the railways: Learning from lived and living experiences. BMC Public Health, 25(1), 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, A., Liesefeld, A. M., & Liesefeld, H. R. (2024). The surprising robustness of visual search against concurrent auditory distraction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 50(1), 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcinkevičiūtė, M., Vilutytė, L., & Gailienė, D. (2024). Experience of pre-suicidal suffering: Insights from suicide attempt survivors. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 19(1), 2370894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, I., Marzano, L., Mosse, D., & Mackenzie, J. M. (2021). First-person accounts of the processes and planning involved in a suicide attempt on the railway. BJPsych Open, 7(1), e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzano, L., Katsampa, D., Mackenzie, J. M., Kruger, I., El-Gharbawi, N., Ffolkes-St-Helene, D., Mohiddin, H., & Fields, B. (2021). Patterns and motivations for method choices in suicidal thoughts and behaviour: Qualitative content analysis of a large online survey. BJPsych Open, 7(2), e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzano, L., Mackenzie, J. M., Kruger, I., Borrill, J., & Fields, B. (2019). Factors deterring and prompting the decision to attempt suicide on the railway networks: Findings from 353 online surveys and 34 semi-structured interviews. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 215(4), 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzano, L., Spence, R., Marsh, I., Barbin, A., & Kruger, I. (2025). How does news coverage of suicide affect suicidal behaviour at a high-frequency location? A 7-year time series analysis. BMJ Public Health, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi, T., Sawada, Y., & Ueda, M. (2013). Does the installation of blue lights on train platforms prevent suicide? A before-and-after observational study from Japan. Journal of Affective Disorders, 147(1), 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsubayashi, T., Sawada, Y., & Ueda, M. (2014). Does the installation of blue lights on train platforms shift suicide to another station?: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Affective Disorders, 169, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May, A. M., & Klonsky, E. D. (2013). Assessing motivations for suicide attempts: Development and psychometric properties of the inventory of motivations for suicide attempts. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 43(5), 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, A. M., Pachkowski, M. C., & Klonsky, E. D. (2020). Motivations for suicide: Converging evidence from clinical and community samples. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 123, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milyavskaya, M., & Werner, K. M. (2018). Goal pursuit: Current state of affairs and directions for future research. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 59(2), 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishara, B. L., & Bardon, C. (2016). Systematic review of research on railway and urban transit system suicides. Journal of Affective Disorders, 193, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohl, A., Stulz, N., Martin, A., Eigenmann, F., Hepp, U., Hüsler, J., & Beer, J. H. (2012). The “Suicide Guard Rail”: A minimal structural intervention in hospitals reduces suicide jumps. BMC Research Notes, 5(1), 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention (NASP), Region Stockholm & Karolinska Institutet. (2022). Pilot study of blue LED-lights in high risk environments. In “Suicide prevention traffic administration/NASP” report (pp. 25–33). Available online: https://restrail.eu/toolbox/IMG/pdf/pilot_study_of_blue_led-lights_in_high_risk_environments-stockholm-v.1.0.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2018). Preventing suicide in community and custodial settings (NICE Guideline NG105). Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng105 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Nischler, C., Michael, R., Wintersteller, C., Marvan, P., van Rijn, L. J., Coppens, J. E., van den Berg, T. J. T. P., Emesz, M., & Grabner, G. (2013). Iris color and visual functions. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology, 251(1), 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, H., Marzano, L., Fields, B., Brown, S., MacDonald Hart, S., & Kruger, I. (2024). Characteristics and circumstances of rail suicides in England 2019–2021: A cluster analysis and autopsy study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 354, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, H., Marzano, L., Winter, R., Crivatu, I., Mackenzie, J. M., & Marsh, I. (2023). Factors prompting and deterring suicides on the roads. BJPsych Open, 9(3), e81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, R. C., O’Carroll, R. E., Ryan, C., & Smyth, R. (2012). Self-regulation of unattainable goals in suicide attempters: A two year prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 142(1), 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Office for National Statistics. (2023, December 19). Suicides in England and Wales: 2022 registrations. Statistical bulletin. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2022registrations (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Okada, A., & Oshima, T. (2025). Assessing the potential of half-height platform screen doors to prevent personal injury accidents: Evidence from the Tokyo metropolitan area railway network. IATSS Research, 49(1), 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei, K. K., Obiri-Yeboah, A. A., Adu-Gyamfi, Lord, & Ackaah, W. (2024). Road crossing behavior and preferences among pedestrians: From the lens of the theory of interpersonal behavior. Traffic Injury Prevention, 25(1), 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, C., Derges, J., & Abraham, C. (2019). Intervening to prevent a suicide in a public place: A qualitative study of effective interventions by lay people. BMJ Open, 9(11), e032319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owens, C., Hardwick, R., Charles, N., & Watkinson, G. (2015). Preventing suicides in public places: A practice resource (No. 2015497). Public Health England. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5c2f6f8b40f0b66cf8298a70/Preventing_suicides_in_public_places.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Özen-Akın, G., & Cinan, S. (2022). People with jumping to conclusions bias tend to make context-independent decisions rather than context-dependent decisions. Consciousness and Cognition, 98, 103279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmentier, F. B. R., Elsley, J. V., Andrés, P., & Barceló, F. (2011a). Why are auditory novels distracting? Contrasting the roles of novelty, violation of expectation and stimulus change. Cognition, 119(3), 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmentier, F. B. R., Ljungberg, J. K., Elsley, J. V., & Lindkvist, M. (2011b). A behavioral study of distraction by vibrotactile novelty. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 37(4), 1134–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinado, V., Valiente, C., Contreras, A., Trucharte, A., & Vázquez, C. (2024). Unravelling the jumping to conclusions bias in daily life and health-related decision-making scenarios. Personality and Individual Differences, 230, 112782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, A. R. (2007). Preventing suicide by jumping: The effect of a bridge safety fence. Injury Prevention, 13(1), 57–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perron, S., Burrows, S., Fournier, M., Perron, P.-A., & Ouellet, F. (2013). Installation of a bridge barrier as a suicide prevention strategy in Montréal, Québec, Canada. American Journal of Public Health, 103(7), 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirkis, J., Too, L. S., Spittal, M. J., Krysinska, K., Robinson, J., & Cheung, Y. T. D. (2015). Interventions to reduce suicides at suicide hotspots: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(11), 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitman, A., Logeswaran, Y., McDonald, K., Cerel, J., Lewis, G., & Erlangsen, A. (2023). Investigating risk of self-harm and suicide on anniversaries after bereavement by suicide and other causes: A Danish population-based self-controlled case series study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 32, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Player, M. J., Proudfoot, J., Fogarty, A., Whittle, E., Spurrier, M., Shand, F., Christensen, H., Hadzi-Pavlovic, D., & Wilhelm, K. (2015). What interrupts suicide attempts in men: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 10(6), e0128180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plessow, F., Fischer, R., Kirschbaum, C., & Goschke, T. (2011). Inflexibly focused under stress: Acute psychosocial stress increases shielding of action goals at the expense of reduced cognitive flexibility with increasing time lag to the stressor. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(11), 3218–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punton, G., Dodd, A. L., & McNeill, A. (2022). ‘You’re on the waiting list’: An interpretive phenomenological analysis of young adults’ experiences of waiting lists within mental health services in the UK. PLoS ONE, 17(3), e0265542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauschenberg, C., Reininghaus, U., ten Have, M., de Graaf, R., van Dorsselaer, S., Simons, C. J. P., Gunther, N., Henquet, C., Pries, L. K., Guloksuz, S., Bak, M., & van Os, J. (2021). The jumping to conclusions reasoning bias as a cognitive factor contributing to psychosis progression and persistence: Findings from NEMESIS-2. Psychological Medicine, 51(10), 1696–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisch, T., & Michel, K. (2005). Securing a suicide hot spot: Effects of a safety net at the bern muenster terrace. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35(4), 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reitz, S., Kluetsch, R., Niedtfeld, I., Knorz, T., Lis, S., Paret, C., Kirsch, P., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Treede, R. D., Baumgärtner, U., Bohus, M., & Schmahl, C. (2015). Incision and stress regulation in borderline personality disorder: Neurobiological mechanisms of self-injurious behaviour. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 207(2), 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritunnano, R., Kleinman, J., Oshodi, D. W., Michail, M., Nelson, B., Humpston, C. S., & Broome, M. R. (2022). Subjective experience and meaning of delusions in psychosis: A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(6), 458–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, D. H. (1975). Suicide survivors. Western Journal of Medicine, 122(4), 289–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ross, V., Koo, Y. W., & Kõlves, K. (2020). A suicide prevention initiative at a jumping site: A mixed-methods evaluation. EClinicalMedicine, 19, 100265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, B. (2017). What do we know about rail suicide incidents? An analysis of 257 fatalities on the rail network in Great Britain. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part F: Journal of Rail and Rapid Transit, 231(10), 1150–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B., Hallewell, M., Hughes, N., Coad, N., Eliseu, J., Lira, M., Grant, A., Parrott, N., & Thompson, K. (2022). Field testing two innovative lighting interventions to influence waiting behaviours and movements on stairways in train stations. Lighting Research & Technology, 54(3), 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel, I., Linden, D., & Escera, C. (2010). Attention capture by novel sounds: Distraction versus facilitation. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 22(4), 481–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæheim, A., Hestetun, I., Mork, E., Nrugham, L., & Mehlum, L. (2017). A 12-year national study of suicide by jumping from bridges in Norway. Archives of Suicide Research, 21(4), 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schomaker, J., & Meeter, M. (2015). Short- and long-lasting consequences of novelty, deviance and surprise on brain and cognition. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 55, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrooten, M. G., Vlaeyen, J. W. S., & Morley, S. (2012). Psychological interventions for chronic pain: Reviewed within the context of goal pursuit. Pain Management, 2(2), 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schunk, D. H., & Usher, E. L. (2012). Social cognitive theory and motivation. In The Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 13–27). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J. Y., Friedman, R., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2002). Forgetting all else: On the antecedents and consequences of goal shielding. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1261–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharot, T., Rollwage, M., Sunstein, C. R., & Fleming, S. M. (2023). Why and when beliefs change. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(1), 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S., Pirkis, J., Clapperton, A., & Spittal, M. (2025). Change in suicides during and after the installation of barriers at the Golden Gate Bridge. Injury Prevention. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S., Pirkis, J., Clapperton, A., Spittal, M., & Too, L. S. (2024). Effectiveness of partial restriction of access to means in jumping suicide: Lessons from four bridges in three countries. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 33, e38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinyor, M., & Levitt, A. J. (2010). Effect of a barrier at Bloor Street Viaduct on suicide rates in Toronto: Natural experiment. BMJ, 341, c2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skegg, K., & Herbison, P. (2009). Effect of restricting access to a suicide jumping site. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(6), 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P. N., & Cukrowicz, K. C. (2010). Capable of suicide: A functional model of the acquired capability component of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(3), 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanchak, K., Foderaro, F., & da Silva, M. (2015). High-security fencing for rail right-of-way applications: Current use and best practices (Technical Report No. DOT-VNTSC-FRA-14-08). U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Railroad Administration. Available online: https://railroads.dot.gov/elibrary/high-security-fencing-rail-right-way-applications-current-use-and-best-practices (accessed on 27 March 2025).

- Steidle, A., & Werth, L. (2014). In the spotlight: Brightness increases self-awareness and reflective self-regulation. Light, Lighting, and Human Behaviour, 39, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, O. (2016). Suicidal journeys: Attempted suicide as geographies of intended death. Social & Cultural Geography, 17(2), 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadmon, D., & Bearman, P. S. (2023). Differential spatial-social accessibility to mental health care and suicide. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 120(19), e2301304120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terman, J. S., & Terman, M. (1999). Photopic and scotopic light detection in patients with seasonal affective disorder and control subjects. Biological Psychiatry, 46(12), 1642–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Too, L. S., Pirkis, J., Milner, A., Bugeja, L., & Spittal, M. J. (2017). Railway suicide clusters: How common are they and what predicts them? Injury Prevention, 23(5), 328–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Too, L. S., Spittal, M. J., Bugeja, L., Milner, A., Stevenson, M., & McClure, R. (2015). An investigation of neighborhood-level social, economic and physical factors for railway suicide in Victoria, Australia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H. C. (1977). Interpersonal behavior. Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, M., Sawada, Y., & Matsubayashi, T. (2015). The effectiveness of installing physical barriers for preventing railway suicides and accidents: Evidence from Japan. Journal of Affective Disorders, 178, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valach, L., Michel, K., & Young, R. A. (2016). Suicide as a distorted goal-directed process: Wanting to die, killing, and being killed. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(11), 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valach, L., Michel, K., Young, R. A., & Dey, P. (2006). Suicide attempts as social goal-directed systems of joint careers, projects, and actions. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 36(6), 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandewalle, G., Balteau, E., Phillips, C., Degueldre, C., Moreau, V., Sterpenich, V., Albouy, G., Darsaud, A., Desseilles, M., & Dang-Vu, T. T. (2006). Daytime light exposure dynamically enhances brain responses. Current Biology, 16(16), 1616–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Houwelingen, C., Baumert, J., Kerkhof, A., Beersma, D., & Ladwig, K.-H. (2013). Train suicide mortality and availability of trains: A tale of two countries. Psychiatry Research, 209(3), 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, A., & Marshall, A. (2010). The support needs and experiences of suicidally bereaved family and friends. Death Studies, 34(7), 625–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. (2023). Preventing suicide: A resource for media professionals, update 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/372691/9789240076846-eng.pdf?sequence=1#page=13.12 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- World Health Organisation. (2025, March 25). Suicide 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Xing, Y., Lu, J., & Chen, S. (2019). Evaluating the effectiveness of platform screen doors for preventing metro suicides in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 253, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joyner, L.; Mackenzie, J.-M.; Willis, A.; Phillips, P.; Cliffe, B.; Marsh, I.; Pettersen, E.; Hawton, K.; Marzano, L. Suicide Prevention Measures at High-Risk Locations: A Goal-Directed Motivation Perspective. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081009

Joyner L, Mackenzie J-M, Willis A, Phillips P, Cliffe B, Marsh I, Pettersen E, Hawton K, Marzano L. Suicide Prevention Measures at High-Risk Locations: A Goal-Directed Motivation Perspective. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081009

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoyner, Laura, Jay-Marie Mackenzie, Andy Willis, Penny Phillips, Bethany Cliffe, Ian Marsh, Elizabeth Pettersen, Keith Hawton, and Lisa Marzano. 2025. "Suicide Prevention Measures at High-Risk Locations: A Goal-Directed Motivation Perspective" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081009

APA StyleJoyner, L., Mackenzie, J.-M., Willis, A., Phillips, P., Cliffe, B., Marsh, I., Pettersen, E., Hawton, K., & Marzano, L. (2025). Suicide Prevention Measures at High-Risk Locations: A Goal-Directed Motivation Perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1009. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081009