Effects of a Digital, Person-Centered, Photo-Activity Intervention on the Social Interaction of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia, Their Informal Carers and Formal Carers: An Explorative Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

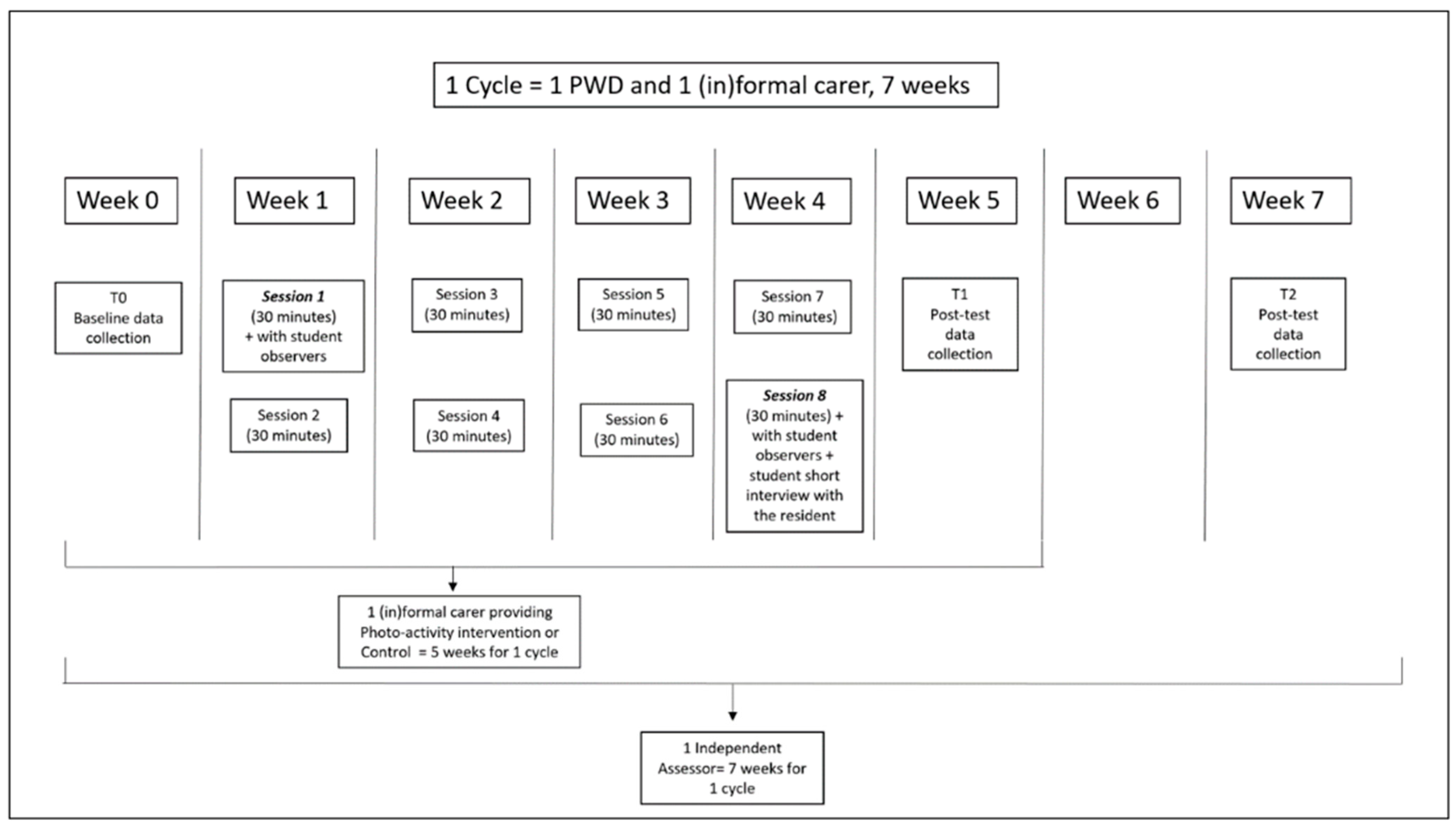

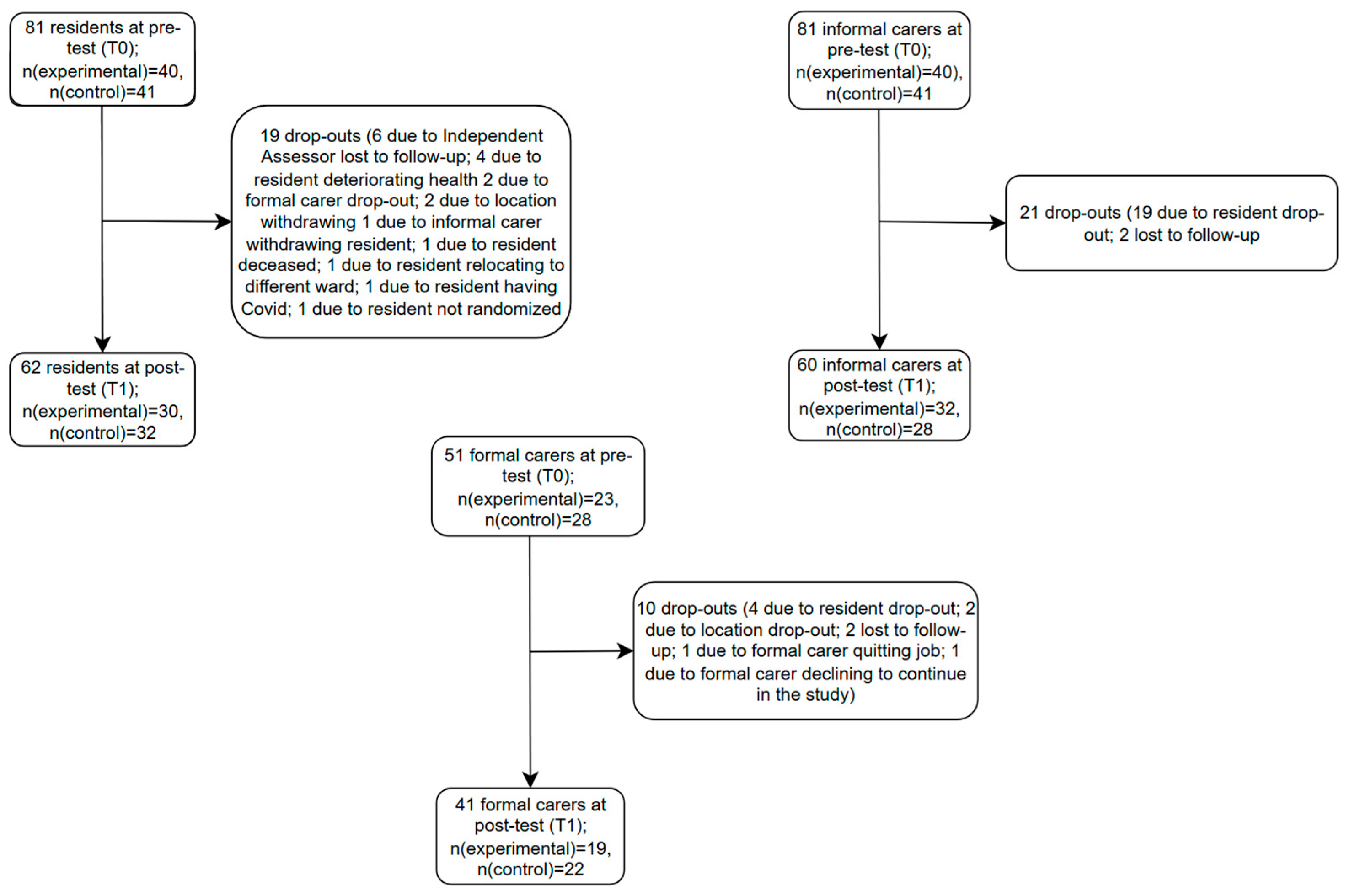

2.1. Design and Randomization Procedure

2.2. Setting and Participants

2.3. Interventions

2.3.1. Digital Photo-Activity (Experimental)

2.3.2. General Conversation Activity (Control)

2.4. Outcome Measures and Procedure of Data Collection

2.4.1. Primary Outcomes

Residents

2.4.2. Secondary Outcomes

Residents

Informal Carers

Formal Carers

2.5. Procedure

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Primary Outcomes

3.2. Secondary Outcomes

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

4.2. Scientific and Clinical Value of the Study and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADQ | Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire |

| ANCOVA | Analysis of covariance |

| DS | Dementia Severity |

| GDS | Global Deterioration Scale |

| IBM | International Business Machines Corporation |

| INTERDEM | Early Detection and timely INTERvention in DEMentia |

| IRI | Interpersonal Reactivity Index |

| MMRM | Mixed model for repeated measures |

| NPI-Q | Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire |

| PA | Photo-Activity |

| Qol | Quality of Life |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| SFAS | Smiley Face Assessment Scale |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| SSCQ | Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire |

| TOPICS-MDS | The Older Persons and Informal Caregivers Survey Minimum Data Set |

References

- Adlbrecht, L., Nemeth, T., Frommlet, F., Bartholomeyczik, S., & Mayer, H. (2022). Engagement in purposeful activities and social interactions amongst persons with dementia in special care units compared to traditional nursing homes: An observational study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 36(3), 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aëgerter, L. (2017). Photographic treatment. Available online: https://photographictreatment.com/en/ (accessed on 30 November 2024).

- Almberg, B., Grafström, M., Krichbaum, K., & Winblad, B. (2000). The interplay of institution and family caregiving: Relations between patient hassles, nursing home hassles and caregivers’ burnout. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(10), 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astell, A. J., Bouranis, N., Hoey, J., Lindauer, A., Mihailidis, A., Nugent, C., & Robillard, J. M. (2019). Technology and dementia: The future is now. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 47(3), 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astell, A. J., Ellis, M. P., Alm, N., Dye, R., & Gowans, G. (2010). Stimulating people with dementia to reminisce using personal and generic photographs. International Journal of Computers in Healthcare, 1(2), 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyeung, T. W., Hui, E., Kng, C., & Lee, J. (2013). Attitudes of long-term care staff toward dementia and their related factors. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(1), 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Àstrom, S., Nilsson, M., Norberg, A., & Winblad, B. (1990). Empathy, experience of burnout and attitudes towards demented patients among nursing staff in geriatric care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 15(11), 1236–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åström, S., Nilsson, M., Norberg, A., Sandman, P.-O., & Winblad, B. (1991). Staff burnout in dementia care—Relations to empathy and attitudes. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 28(1), 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R., Bell, S., Baker, E., Holloway, J., Pearce, R., Dowling, Z., Thomas, P., Assey, J., & Wareing, L. (2001). A randomized controlled trial of the effects of multi-sensory stimulation (MSS) for people with dementia. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(1), 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, R., & Dowling, Z. (1995). Interact. A new measure of response to multi-sensory environments. Research publication. Research and Development Support Unit, Poole Hospital, Dorset. [Google Scholar]

- Bates-Jensen, B. M., Alessi, C. A., Cadogan, M., Levy-Storms, L., Jorge, J., Yoshii, J., Al-Samarrai, N. R., & Schnelle, J. F. (2004). The minimum data set bedfast quality indicator: Differences among nursing homes. Nursing Research, 53(4), 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boersma, P., van Weert, J. C. M., Lissenberg-Witte, B. I., van Meijel, B., & Dröes, R.-M. (2018). Testing the implementation of the Veder contact method: A theatre-based communication method in dementia care. The Gerontologist, 59(4), 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boersma, P., Van Weert, J. C. M., van Meijel, B., van de Ven, P. M., & Dröes, R.-M. (2017). Study protocol Implementation of the Veder contact method (VCM) in daily nursing home care for people with dementia: An evaluation based on the RE-AIM framework. Aging & Mental Health, 21(7), 730–741. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, P., Camic, P. M., & Crutch, S. J. (2021). Psychosocial outcomes of dyadic arts interventions for people with a dementia and their informal caregivers: A systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 29(6), 1632–1649. [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty, H., Burns, K., & Sury, L. (2013). Moving in: Adjustment of people living with dementia going into a nursing home and their families. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooker, D. (2003). What is person-centred care in dementia? Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 13(3), 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. L., Agronin, M. E., & Stein, J. R. (2020). Interventions to enhance empathy and person-centered care for individuals with dementia: A systematic review. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 13(3), 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buettner, L. L. (1999). Simple Pleasures: A multilevel sensorimotor intervention for nursing home residents with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 14(1), 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, H., Walsh, S., Cooper, C., & Livingston, G. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence and associations of stress and burnout among staff in long-term care facilities for people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(8), 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, M. H. (1980). A multidimensional approach to individual differences in empathy. JSAS Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 10, 85. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Corte, K., Buysse, A., Verhofstadt, L. L., Roeyers, H., Ponnet, K., & Davis, M. H. (2007). Measuring empathic tendencies: Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Psychologica Belgica, 47(4), 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonghe, J., Kat, M. G., Kalisvaart, C., & Boelaarts, L. (2003). Neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire (NPI-Q): A validity study of the Dutch form. Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr, 34(2), 74–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- de Vries, K., Drury-Ruddlesden, J., & McGill, G. (2020). Investigation into attitudes towards older people with dementia in acute hospital using the Approaches to Dementia Questionnaire. Dementia, 19(8), 2761–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vugt, M., & Dröes, R.-M. (2017). Social health in dementia. Towards a positive dementia discourse. Aging & Mental Health, 21(1), 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickinson, C., Dow, J., Gibson, G., Hayes, L., Robalino, S., & Robinson, L. (2017). Psychosocial intervention for carers of people with dementia: What components are most effective and when? A systematic review of systematic reviews. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(1), 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dröes, R. M., Chattat, R., Diaz, A., Gove, D., Graff, M., Murphy, K., Verbeek, H., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Clare, L., Johannessen, A., Roes, M., Verhey, F., Charras, K., & The INTERDEM sOcial Health Taskforce. (2017). Social health and dementia: A European consensus on the operationalization of the concept and directions for research and practice. Aging & Mental Health, 21(1), 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Duru Aşiret, G., & Kapucu, S. (2016). The effect of reminiscence therapy on cognition, depression, and activities of daily living for patients with Alzheimer disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 29(1), 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettema, T. P., Dröes, R. M., De Lange, J., Mellenbergh, G. J., & Ribbe, M. W. (2007a). QUALIDEM: Development and evaluation of a dementia specific quality of life instrument. Scalability, reliability and internal structure. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A Journal of the Psychiatry of Late Life and Allied Sciences, 22(6), 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettema, T. P., Dröes, R. M., de Lange, J., Mellenbergh, G. J., & Ribbe, M. W. (2007b). QUALIDEM: Development and evaluation of a dementia specific quality of life instrument––Validation. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: A Journal of the Psychiatry of Late Life and Allied Sciences, 22(5), 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francillon, A., Pickering, G., & Belorgey, C. (2009). Exploratory clinical trials: Implementation modes & guidelines, scope and regulatory framework. Therapie, 64(3), 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler, J. E., Pearlin, L. I., Leitsch, S. A., & Davey, A. (2001). Relinquishing in-home dementia care: Difficulties and preceived helpfulness during the nursing home trasition. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 16(1), 32–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhard, D., & Frank, J. I. (2024). Everyday life and boredom of people living with dementia in residential long-term care: A merged methods study. BMC Geriatrics, 24(1), 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, D., van der Roest, H., Evans, S., Leontjevas, R., Prins, M., Brooker, D., & Dröes, R. M. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the well-being of people living with dementia. In Dementia and society (pp. 193–210). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108918954. [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen, D. L., van Beek, A. P. A., & Woods, R. T. (2019). Relationship of care staff attitudes with social well-being and challenging behavior of nursing home residents with dementia: A cross sectional study. Aging & Mental Health, 23(11), 1517–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitlin, L. N., Marx, K., Piersol, C. V., Hodgson, N. A., Huang, J., Roth, D. L., & Lyketsos, C. (2021). Effects of the tailored activity program (TAP) on dementia-related symptoms, health events and caregiver wellbeing: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatrics, 21, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, D. A., Finley, J.-C. A., Patel, S. E. S., & Soble, J. R. (2025). Practical assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms: Updated reliability, validity, and cutoffs for the neuropsychiatric inventory questionnaire. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(5), 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haight, B. K., Bachman, D. L., Hendrix, S., Wagner, M. T., Meeks, A., & Johnson, J. (2003). Life review: Treating the dyadic family unit with dementia. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 10(3), 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Han, A. (2020). Interventions for attitudes and empathy toward people with dementia and positive aspects of caregiving: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Research on Aging, 42(2), 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendriks, I., Meiland, F. J., Gerritsen, D. L., & Dröes, R.-M. (2021). Evaluation of the ‘Unforgettable’ art programme by people with dementia and their care-givers. Ageing & Society, 41(2), 294–312. [Google Scholar]

- Henskens, M., Nauta, I. M., Vrijkotte, S., Drost, K. T., Milders, M. V., & Scherder, E. J. A. (2019). Mood and behavioral problems are important predictors of quality of life of nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE, 14(12), e0223704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoe, J., Hancock, G., Livingston, G., & Orrell, M. (2006). Quality of life of people with dementia in residential care homes. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(5), 460–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, L. J., van Haastregt, J. C., de Vries, E., Backhaus, R., Hamers, J. P., & Verbeek, H. (2021). Partnerships in nursing homes: How do family caregivers of residents with dementia perceive collaboration with staff? Dementia, 20(5), 1631–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoel, V., Seibert, K., Domhoff, D., Preuß, B., Heinze, F., Rothgang, H., & Wolf-Ostermann, K. (2022). Social health among german nursing home residents with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the role of technology to promote social participation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(4), 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., Altman, D. G., Barbour, V., Macdonald, H., Johnston, M., Lamb, S. E., Dixon-Woods, M., McCulloch, P., Wyatt, J. C., Chan, A., & Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopewell, S., Chan, A.-W., Collins, G. S., Hróbjartsson, A., Moher, D., Schulz, K. F., Tunn, R., Aggarwal, R., Berkwits, M., Berlin, J. A., Bhandari, N., Butcher, N. J., Campbell, M. K., Chidebe, R. C. W., Elbourne, D., Farmer, A., Fergusson, D. A., Golub, R. M., Goodman, S. N., … Boutron, I. (2025). CONSORT 2025 explanation and elaboration: Updated guideline for reporting randomised trials. BMJ, 389, e081124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jao, Y.-L., Loken, E., MacAndrew, M., Van Haitsma, K., & Kolanowski, A. (2018). Association between social interaction and affect in nursing home residents with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 22(6), 778–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufer, D. I., Cummings, J. L., Ketchel, P., Smith, V., MacMillan, A., Shelley, T., Lopez, O. L., & DeKosky, S. T. (2000). Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 12(2), 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitwood, T., & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing & Society, 12(3), 269–287. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, W. Q., Heins, P., Flynn, A., Mahmoudi Asl, A., Garcia, L., Malinowsky, C., & Brorsson, A. (2024). Bridging gaps in the design and implementation of socially assistive technologies for dementia care: The role of occupational therapy. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 19(3), 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivula, A., Räsänen, P., & Sarpila, O. (2019, July 26–31). Examining social desirability bias in online and offline surveys [Paper presentation]. International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, Orlando, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kolanowski, A., Litaker, M., Buettner, L., Moeller, J., Costa, J., & Paul, T. (2011). A randomized clinical trial of theory-based activities for the behavioral symptoms of dementia in nursing home residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(6), 1032–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolanowski, A. M., Litaker, M., & Buettner, L. (2005). Efficacy of theory-based activities for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Nursing Research, 54(4), 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, V., Fossey, J., Ballard, C., Ferreira, N., & Murray, J. (2016). Helping staff to implement psychosocial interventions in care homes: Augmenting existing practices and meeting needs for support. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(3), 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, V., Fossey, J., Ballard, C., Moniz-Cook, E., & Murray, J. (2012). Improving quality of life for people with dementia in care homes: Making psychosocial interventions work. British Journal of Psychiatry, 201(5), 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lintern, T. C. (2001). Quality in dementia care: Evaluating staff attitudes and behaviour. Bangor University (United Kingdom). [Google Scholar]

- Livingston, L., Fiterman Persin, G., & Del Signore, D. (2016). Art in the moment: Evaluating a therapeutic wellness program for people with dementia and their care partners. Journal of Museum Education, 41(2), 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutomski, J. E., Baars, M. A., Schalk, B. W., Boter, H., Buurman, B. M., den Elzen, W. P. J., Jansen, A. P. D., Kempen, G. I. J. M., Steunenberg, B., Steyerberg, E. W., Rikkert, M. G. M. O., Melis, R. J. F., on behalf of TOPICS-MDS Consortium & Bayer, A. (2013). The development of the Older Persons and Informal Caregivers Survey Minimum DataSet (TOPICS-MDS): A large-scale data sharing initiative. PLoS ONE, 8(12), e81673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabire, J.-B., Gay, M.-C., Charras, K., & Vernooij-Dassen, M. (2022). Impact of a psychosocial intervention on social interactions between people with dementia: An observational study in a nursing home. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 46(1), 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, M., Brown, L. J., Muller, C., Vikram, A., & Berry, K. (2023). The impact of psychosocial training on staff attitudes towards people living with dementia: A systematic review. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 18(3), e12528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merrick, K., Camic, P. M., & O’Shaughnessy, M. (2016). Couples constructing their experiences of dementia: A relational perspective. Dementia, 15(1), 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, D. P., Ettema, T. P., Zwan, M. D., Dijkstra, K., Finnema, E., Graff, M., Muller, M., & Dröes, R.-M. (2023). FindMyApps compared with usual tablet use to promote social health of community-dwelling people with mild dementia and their informal caregivers: A randomised controlled trial. eClinicalMedicine, 63, 102169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapaport, P., Livingston, G., Murray, J., Mulla, A., & Cooper, C. (2017). Systematic review of the effective components of psychosocial interventions delivered by care home staff to people with dementia. BMJ Open, 7(2), e014177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisberg, B., Ferris, S. H., de Leon, M. J., & Crook, T. (1982). The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 139(9), 1136–1139. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Riedijk, S., Duivenvoorden, H., Van Swieten, J., Niermeijer, M., & Tibben, A. (2009). Sense of competence in a Dutch sample of informal caregivers of frontotemporal dementia patients. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 27(4), 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, F. (2009). The MoMA Alzheimer’s Project: Programming and resources for making art accessible to people with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers. Arts & Health, 1(1), 93–97. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, A. S., Yamamoto, E., & Shiotani, H. (2005). Positive affect among nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s dementia: The effect of recreational activity. Aging & Mental Health, 9(2), 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Spector, A., Revolta, C., & Orrell, M. (2016). The impact of staff training on staff outcomes in dementia care: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(11), 1172–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tak, S. H., Beck, C., & Hong, S. H. (2013). Feasibility of providing computer activities for nursing home residents with dementia. Non-Pharmacological Therapies in Dementia, 3(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tak, S. H., Kedia, S., Tongumpun, T. M., & Hong, S. H. (2015). Activity engagement: Perspectives from nursing home residents with dementia. Educational Gerontology, 41(3), 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J. R. O., Boersma, P., Ettema, T. P., Aëgerter, L., Gobbens, R., Stek, M. L., & Dröes, R.-M. (2022). Known in the nursing home: Development and evaluation of a digital person-centered artistic photo-activity intervention to promote social interaction between residents with dementia, and their formal and informal carers. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J. R. O., Boersma, P., Ettema, T. P., Planting, C. H., Clark, S., Gobbens, R. J., & Dröes, R.-M. (2023). The effects of psychosocial interventions using generic photos on social interaction, mood and quality of life of persons with dementia: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J. R. O., Neal, D. P., Vilmen, M., Boersma, P., Ettema, T. P., Gobbens, R. J., Sikkes, S. A. M., & Dröes, R.-M. (2025). A digital photo activity intervention for nursing home residents with dementia and their carers: Mixed methods process evaluation. JMIR Formative Research, 9, e56586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teahan, Á., Lafferty, A., McAuliffe, E., Phelan, A., O’Sullivan, L., O’Shea, D., Nicholson, E., & Fealy, G. (2020). Psychosocial interventions for family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(9), 1198–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Temple, R. O., Stern, R. A., Latham, J., Ruffolo, J. S., Arruda, J. E., & Tremont, G. (2004). Assessment of mood state in dementia by use of the Visual Analog Mood Scales (VAMS). The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 12(5), 527–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theijsmeijer, S., de Boo, G. M., & Dröes, R.-M. (2018). A pilot study into person-centred use of photo’s in the communication with people with dementia. Tijdschrift voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie, 49, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tolson, D., & Schofield, I. (2012). Football reminiscence for men with dementia: Lessons from a realistic evaluation. Nursing Inquiry, 19(1), 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tominari, M., Uozumi, R., Becker, C., & Kinoshita, A. (2021). Reminiscence therapy using virtual reality technology affects cognitive function and subjective well-being in older adults with dementia. Cogent Psychology, 8(1), 1968991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diepen, E., Baillon, S. F., Redman, J., Rooke, N., Spencer, D. A., & Prettyman, R. (2002). A pilot study of the physiological and behavioural effects of Snoezelen in dementia. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(2), 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Haeften-van Dijk, A. M., Meiland, F. J., Hattink, B. J., Bakker, T. J., & Dröes, R.-M. (2020). A comparison of a community-based dementia support programme and nursing home-based day care: Effects on carer needs, emotional burden and quality of life. Dementia, 19(8), 2836–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Haitsma, K. S., Curyto, K., Abbott, K. M., Towsley, G. L., Spector, A., & Kleban, M. (2013). A Randomized Controlled Trial for an Individualized Positive Psychosocial Intervention for the Affective and Behavioral Symptoms of Dementia in Nursing Home Residents. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 70(1), 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandrevala, T., Samsi, K., Rose, C., Adenrele, C., Barnes, C., & Manthorpe, J. (2017). Perceived needs for support among care home staff providing end of life care for people with dementia: A qualitative study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M., Felling, A., Brummelkamp, E., Dauzenberg, M., Van Den Bos, G., & Grol, R. (1999). Assessment of caregiver’s competence in dealing with the burden of caregiving for a dementia patient: A short sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ) suitable for clinical practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47(2), 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernooij-Dassen, M., Kurz, X., Scuvee-Moreau, J., & Dresse, A. (2003). The measurement of sense of competence in caregivers of patients with dementia. Revue D’epidemiologie et de Sante Publique, 51(2), 227–235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, J., & Wang, B. (2020). Efficacy of VR-based reminiscence therapy in improving autobiographical memory for Chinese patients with AD. In Advances in ergonomics in design: Proceedings of the AHFE 2020 virtual conference on ergonomics in design, July 16–20, 2020, USA. Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | T0 | During Intervention Period | T1 | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Assistant/Resident with dementia | INTERACT Observation Scale (Session 1 and 8) | |||

| Independent Assessor | QUALIDEM NPI-Q | QUALIDEM NPI-Q | QUALIDEM NPI-Q | |

| Resident with dementia | GDS (via ward Coordinator) | SFAS (1st and 4th intervention week) | ||

| Formal Carer | TOPICS-MDS ADQ IRI | ADQ IRI | ||

| Informal Carer | TOPICS-MDS SSCQ | SSCQ | SSCQ |

| Residents | Informal Carers | Formal Carers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Exp (N = 40) | Control (N = 41) | Difference Test | p | Exp (N = 40) | Control (N = 41) | Difference Test | p | Exp (N = 23) | Control (N = 28) | Difference Test | p |

| Sex n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Female | 33 (82.5) | 32 (78.0) | χ2 = 0.050 a | 0.823 | 9 (22.5) | 11 (27.5) | χ2 = 0.038 a | 0.846 | 1 (4.3) | 1 (3.6) | χ2 < 0.000 a,b | 1.000 |

| Age M (SD), [min-max] | 84.58 (7.52), [68–96] | 85.18 (7.38), [62–96] | t(74) = 0.354 | 0.724 | 58.00 (1.455), [31–75] | 59.00 (1.725), [27–84] | U = 619.500 Z = −1.240 | 0.215 | 50.00 (2.707), [20–62] | 51.50 (2.776), [18–63] | U = 309.000 Z = −0.246 | 0.805 |

| Marital Status n (%) | ||||||||||||

| 1 = Married | 10 (25) | 8 (19.5) | χ2 = 6.377 b | 0.173 | N/A d | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| 2 = Unmarried, no partner | 4 (10) | 0 | ||||||||||

| 3 = Divorced | 3 (7.5) | 5 (12.2) | ||||||||||

| 4 = Widow/widower/partner deceased | 21 (52.5) | 25 (61.0) | ||||||||||

| Place of birth n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Netherlands | 37 (92.5) | 36 (87.8) | χ2 = 0.347 b | 0.556 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Other | 1 (2.5) | 2 (4.9) | ||||||||||

| Education level n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Elementary | 8 (20) | 10 (24.4) | U = 657.500 Z = −0.747 | 0.455 | 0 | 4 (9.8) | U = 710.500 Z = −0.593 | 0.593 | 0 | 0 | U = 292.000 Z = −0.950 | 0.342 |

| Lower Education | 26 (65) | 17 (41.5) | 20 (50) | 13 (31.7) | 21 (91.3) | 23 (82.1) | ||||||

| Advanced Education | 1 (2.5) | 6 (14.6) | 5 (12.5) | 5 (12.2) | 1 (4.3) | 2 (7.1) | ||||||

| University/Higher Education | 3 (7.5) | 5 (12.2) | 13 (32.5) | 18 (43.9) | 1 (4.3) | 3 (10.7) | ||||||

| Type of dementia n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Alzheimer’s Disease | 23 (57.5) | 32 (78) | χ2 = 3.036 a | 0.081 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Vascular dementia | 7 (17.5) | 2 (4.9) | ||||||||||

| Other | 10 (25.0) | 7 (17.1) | ||||||||||

| Severity of dementia n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Mild to moderate (GDS c 4 and 5) | 27 (67.5) | 27 (65.9) | U = 806.500 Z = −0.156 | 0.876 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Severe (GDS c 6) | 13 (32.5) | 14 (34.1) | ||||||||||

| Years in nursing home | ||||||||||||

| n, Mdn (SE), [min–max] | n = 38, 1.050 (0.2200), [0.2–7.0] | n = 37, 1.3 (0.3132), [0.2–10.0] | U = 632.500 Z = −0.748 | 0.454 | ||||||||

| Relation to Resident n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Husband/Wife/Partner | N/A | N/A | 6 (15) | 8 (19.5) | χ2 = 1.051 b | 0.789 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Son/Daughter | 4 (10) | 5 (12.2) | ||||||||||

| Daughter/son-in-law | 24 (60) | 24 (58.5) | ||||||||||

| Other | 4 (10) | 2 (4.9) | ||||||||||

| Paid work | ||||||||||||

| Yes n (%) | N/A | N/A | 27 (67.5) | 23 (56.1) | χ2 = 1.555 | 0.212 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| Hours spent caring for resident in the last week n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Low (0–3 h) | N/A | N/A | 20 (50) | 20 (48.8) | U = 741.500 Z = 0.240 | 0.81 | N/A | N/A | ||||

| High (4 or more hours) | 19 (47.5) | 17 (41.5) | ||||||||||

| Work Function n (%) | ||||||||||||

| Carer | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7 (30.4) | 6 (21.4) | χ2 = 1.931 | 0.587 | ||||

| Nurse | 1 (4.3) | 0 | ||||||||||

| Activity therapist | 4 (17.4) | 6 (21.4) | ||||||||||

| Other | 11 (47.8) | 16 (57.1) | ||||||||||

| Years of work experience in psychogeriatrics Mdn (SE), [min-max] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 4.000 (0.9630), [1.0–16.0] | 5.500 (2.1191), [1.0–40.0] | U = 258.500 Z = −1.212 | 0.226 |

| (a) | ||||||||||||

| Resident | Pre-Test (T0) | Post-Test (T1) | ANCOVA | Effect Size | ||||||||

| Experimental (n = 38) | Control (n = 39) | Experimental (n = 31) | Control (n = 33) | Experimental adjM (SE) | Control adjM (SE) | p | Partial Eta2 | |||||

| INTERACT | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||||

| Mood (range: 0–24) | 19.63 | (4.01) | 17.44 | (4.69) | 19.39 | 3.12 | 16.88 | 3.90 | 18.97 (0.56) | 17.28 (0.54) | 0.037 * | 0.070 |

| Speech (range: 0–20) | 16.17 | (4.03) | 14.94 | (4.16) | 15.45 | 5.14 | 14.36 | 4.47 | 15.12 (0.69) | 14.68 (0.67) | 0.645 | 0.003 |

| Relating to person (range: 0–24) | 19.06 | (3.38) | 17.97 | (2.40) | 18.10 | 3.29 | 17.82 | 2.83 | 17.83 (0.50) | 18.07 (0.48) | 0.733 | 0.002 |

| Relating to environment (range: 0–20) | 15.83 | (3.45) | 14.58 | (4.16) | 14.48 | 3.98 | 15.24 | 4.17 | 14.49 (0.74) | 15.25 (0.72) | 0.473 | 0.008 |

| Need for prompting (range: 0–4) | 2.86 | (1.14) | 2.39 | (1.29) | 2.39 | 1.38 | 2.36 | 1.19 | 2.31 (0.22) | 2.43 (0.21) | 0.685 | 0.003 |

| Stimulation level (range: 0–20) | 17.63 | (2.97) | 16.11 | (3.50) | 17.58 | 2.90 | 16.24 | 3.11 | 17.32 (0.52) | 16.49 (0.50) | 0.261 | 0.021 |

| Negative interactions (range: 0–24) | 23.63 | (0.84) | 22.64 | (2.00) | 23.74 | 0.514 | 22.67 | 1.98 | 23.56 (0.25) | 22.84 (0.25) | 0.053 | 0.060 |

| NPI-Q (range: 0–30) | (n = 35) | (n = 36) | (n = 30) | (n = 32) | ||||||||

| Total Severity Score | 3.00 | (3.24) | 3.97 | (4.65) | 3.17 | (4.56) | 2.97 | (3.62) | 3.42 (0.55) | 2.73 (0.53) | 0.377 | 0.013 |

| SFAS (range: 1–5) | (n = 35) | (n = 35) | (n = 35) | (n = 35) | ||||||||

| Mean SFAS Score of weeks 1 and 4 | 3.57 | (0.59) | 3.38 | (0.64) | 3.92 | (0.64) | 3.83 | (0.69) | 3.87 (0.10) | 3.87 (0.10) | 0.996 | 0.000 |

| Feeling Known (range: 0–10) | (n = 32) | (n = 32) | (n = 25) | (n = 23) | ||||||||

| Known as a person in the nursing home | 7.06 | (1.98) | 6.69 | (2.67) | 7.88 | (1.20) | 7.26 | (2.05) | 7.75 (0.27) | 740 (0.28) | 0.367 | 0.018 |

| (n = 34) | (n = 34) | (n = 25) | (n = 23) | |||||||||

| Satisfied with staying in the nursing home | 7.74 | (1.64) | 7.03 | (2.66) | 8.00 | (1.54) | 7.58 | (1.92) | 7.75 (0.28) | 7.83 (0.28) | 0.845 | 0.001 |

| QUALIDEM | (n = 38) | (n = 39) | (n = 30) | (n = 32) | ||||||||

| Care Relationship (range: 0–21) | 15.39 | (4.27) | 14.46 | (4.47) | 15.90 | (4.08) | 14.91 | (5.01) | 15.50 (0.56) | 15.28 (0.54) | 0.774 | 0.001 |

| Positive Affect (range: 0–18) | 14.21 | (3.81) | 14.69 | (3.12) | 15.20 | (3.69) | 13.69 | (3.85) | 15.12 (0.42) | 13.76 (0.41) | 0.025 * | 0.082 |

| Negative Affect (range: 0–9) | 5.37 | (2.75) | 5.44 | (2.25) | 6.10 | (2.52) | 5.66 | (1.89) | 6.03 (0.25) | 5.72 (0.24) | 0.365 | 0.014 |

| Restless Tense-Behaviour (range: 0–9) | 5.29 | (2.45) | 4.90 | (2.72) | 5.97 | (2.83) | 5.03 | (2.94) | 5.71 (0.37) | 5.27 (0.36) | 0.399 | 0.012 |

| Positive Self-Esteem (range: 0–9) | 6.42 | (2.31) | 6.33 | (1.97) | 7.10 | (2.11) | 6.75 | (2.02) | 7.01 (0.22) | 6.83 (0.21) | 0.558 | 0.006 |

| Social Relationships (range: 0–18) | 10.55 | (2.39) | 10.49 | (2.76) | 11.50 | (2.71) | 10.50 | (2.65) | 11.42 (0.41) | 10.57 (0.39) | 0.137 | 0.037 |

| Social Isolation (range: 0–9) | 6.87 | (2.16) | 6.08 | (2.24) | 7.30 | (1.71) | 6.34 | (1.99) | 7.07 (0.24) | 6.56 (0.23) | 0.138 | 0.037 |

| Feeling at Home (range: 0–12) | 8.66 | (2.87) | 8.59 | (3.39) | 8.97 | (3.49) | 8.50 | (3.23) | 8.79 (0.36) | 8.67 (0.34) | 0.806 | 0.001 |

| Have Something to Do (range: 0–6) | 3.18 | (1.67) | 2.97 | (1.71) | 3.47 | (1.74) | 3.13 | (1.60) | 3.40 (0.23) | 3.18 (0.22) | 0.488 | 0.008 |

| (b) | ||||||||||||

| Informal Carer | Pre-test (T0) | Post-test (T1) | ANCOVA | |||||||||

| Experimental (n = 37) | Control (n = 37) | Experimental (n = 32) | Control (n = 28) | Experimental | Control | p | Effect Size Partial Eta2 | |||||

| SSCQ (range: 7–35) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | adjM (SE) | adjM (SE) | ||

| Sense of Competence | 28.73 | (5.21) | 26.97 | (5.22) | 28.34 | (3.81) | 28.43 | (4.51) | 27.88 (0.57) | 28.96 (0.61) | 0.208 | 0.028 |

| Feeling Known (range: 1–10) | (n = 37) | (n = 37) | (n = 32) | (n = 28) | ||||||||

| Feel seen as the family carer in the nursing home | 8.32 | (1.6) | 8.51 | (1.30) | 8.47 | (1.61) | 8.39 | (1.55) | 8.57 (0.14) | 8.8 (0.15) | 0.159 | 0.034 |

| Satisfied with the stay of your loved one in the nursing home | 8.65 | (1.18) | 8.57 | (1.35) | 8.72 | (1.20) | 8.54 | (1.84) | 8.66 (0.13) | 8.60 (0.14) | 0.729 | 0.002 |

| My loved one with dementia is known in the nursing home | 8.78 | (1.25) | 8.57 | (1.32) | 8.72 | (1.14) | 8.39 | (1.69) | 8.68 (0.16) | 8.44 (0.17) | 0.313 | 0.018 |

| (c) | ||||||||||||

| Formal Carer | Pre-Test (T0) | Post-Test (T1) | ANCOVA | |||||||||

| Experimental (n = 23) | Control (n = 28) | Experimental (n = 19) | Control (n = 22) | Experimental adjM (SE) | Control adjM (SE) | p | Effect Size Partial Eta2 | |||||

| IRI | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | ||||

| Global Empathy (range: 0–112) | 64.04 | (8.46) | 59.86 | (9.34) | 59.58 | (6.45) | 62.36 | (8.70) | 58.07 (1.37) | 63.66 (1.27) | 0.006 * | 0.185 |

| Subscales (range: 0–28) | ||||||||||||

| Perspective Taking | 19.09 | (3.04) | 18.57 | (3.10) | 18.37 | (2.54) | 18.95 | (2.77) | 18.09 (0.47) | 19.19 (0.44) | 0.096 | 0.071 |

| Empathic Concern | 19.09 | (2.80) | 17.36 | (3.42) | 17.95 | (2.51) | 18.73 | (3.07) | 17.32 (0.50) | 19.27 (0.47) | 0.009 * | 0.167 |

| Fantasy | 14.96 | (4.01) | 13.54 | (4.22) | 12.74 | (3.51) | 14.45 | (3.20) | 12.27 (0.60) | 14.86 (0.56) | 0.003 * | 0.203 |

| Personal Distress | 10.91 | (3.34) | 10.39 | (3.56) | 10.53 | (4.21) | 10.28 | (4.12) | 10.41 (0.63) | 10.33 (0.59) | 0.932 | 0.000 |

| ADQ | (n = 23) | (n = 28) | (n = 19) | (n = 22) | ||||||||

| Total ADQ (19–95) | 77.17 | (4.22) | 74.36 | (4.35) | 75.37 | (4.35) | 74.86 | (5.12) | 74.43 (0.99) | 75.68 (0.91) | 0.372 | 0.021 |

| Person-Centered (score range: 11–55) | 49.17 | (3.73) | 47.29 | (3.74) | 48.37 | (3.32) | 47.73 | (3.82) | 47.70 (0.66) | 48.31 (0.61) | 0.507 | 0.012 |

| Hope (score range: 8–40) | 27.91 | (2.37) | 26.86 | (2.32) | 27.21 | (2.44) | 26.95 | (2.54) | 27.09 (0.53) | 27.06 (0.49) | 0.961 | 0.000 |

| (n = 19) | (n = 24) | Difference Test | ||||||||||

| Feeling Known (range: 1–10) Got to know the person with dementia and their loved one better | n/a a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 7.00 | (0.39) | 7.00 | (0.30) | U = 237.000 Z = 0.228 | 0.820 | 0.035 | |

| Feeling Known n(%) a (range: 1–10) Got to know the person with dementia (only) better Yes Much Better Yes a Little Better No, Not Better | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | (n = 23) 9 (39.1) 11 (47.8) 2 (8.7) | (n = 27) 4 (14.8) 17 (63.0) 6 (22.2) | U = 390.500 Z = 2.114 | 0.035 * | 0.299 | |||

| Pre-Test (T0) | Post-Test (T1) | ANCOVA | ||||||||||||

| Experimental (n = 35) | Control (n = 36) | Experimental (n = 31) | Control (n = 33) | Experimental adjM (SE) | Control adjM (SE) | Interaction | p | Effect Size | ||||||

| INTERACT | GDS | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | Partial Eta2 | ||||

| Mood (range: 0–24) | Low | 19.59 | (4.33) | 17.57 | (4.84) | 20.15 | (2.46) | 16.19 | (3.79) | 19.66 (0.68) | 16.59 (0.66) | GroupxGDS | 0.017 * | 0.092 |

| High | 19.69 | (3.57) | 17.23 | (4.60) | 18.00 | (3.80) | 18.08 | (3.97) | 17.71 (0.90) | 18.46 (0.87) | ||||

| Speech (range: 0–20) | Low | 16.27 | (3.67) | 15.30 | (4.07) | 17.10 | (3.52) | 14.76 | (3.65) | 16.53 (0.82) | 14.84 (0.79) | GroupxGDS | 0.075 | 0.053 |

| High | 16.00 | (4.73) | 14.31 | (4.40) | 12.45 | (6.36) | 13.67 | (5.76) | 12.60 (1.09) | 14.34 (1.05) | ||||

| Relating to Person (range: 0–24) | Low | 19.59 | (2.94) | 17.61 | (2.68) | 18.75 | (2.77) | 17.62 | (3.29) | 18.16 (0.64) | 18.06 (0.61) | GroupxGDS | 0.552 | 0.006 |

| High | 18.15 | (3.98) | 18.62 | (1.71) | 16.91 | (3.94) | 18.17 | (1.85) | 17.26 (0.84) | 18.05 (0.80) | ||||

| Relating to Environment | Low | 16.00 | (3.64) | 14.09 | (4.30) | 14.85 | (4.18) | 15.57 | (4.20) | 14.85 (0.94) | 15.57 (0.92) | GroupxGDS | 0.954 | 0.000 |

| (range: 0–20) | High | 15.54 | (3.23) | 15.46 | (3.93) | 13.82 | (3.68) | 14.67 | (4.22) | 13.82 (1.25) | 14.67 (1.20) | |||

| Need for Prompting | Low | 2.77 | (1.11) | 2.22 | (1.28) | 2.90 | (1.17) | 2.29 | (1.27) | 2.84 (0.25) | 2.45 (0.25) | GroupxGDS | 0.013 * | 0.099 |

| (range: 0–4) | High | 3.00 | (1.23) | 2.69 | (1.32) | 1.45 | (1.29) | 2.50 | (1.09) | 1.33 (0.33) | 2.42 (0.32) | |||

| Stimulation level | Low | 17.64 | (2.94) | 15.96 | (3.62) | 18.45 | (1.91) | 15.62 | (3.43) | 18.17 (0.62) | 15.95 (0.61) | GroupxGDS | 0.011 * | 0.106 |

| (range: 0–20) | High | 17.62 | (3.15) | 16.38 | (3.40) | 16.00 | (3.74) | 17.33 | (2.19) | 15.83 (0.83) | 17.38 (0.79) | |||

| Negative Interactions | Low | 23.68 | (0.65) | 22.87 | (1.91) | 23.75 | (0.44) | 22.38 | (2.22) | 23.52 (0.31) | 22.48 (0.30) | GroupxGDS | 0.166 | 0.032 |

| (range: 0–24) | High | 23.54 | (1.13) | 22.23 | (2.17) | 23.73 | (0.65) | 23.17 | (1.40) | 23.57 (0.41) | 23.52 (0.40) | |||

| Means | Effect Estimate (GroupxTime Interaction) | p-Value | Effect Size (Cohen’s d) | ||||

| Qualidem Subscales (Range) | T0 | T1 | T2 | ||||

| Care Relationships (0–21) | |||||||

| Experimental | 15.96 | 16.34 | 16.09 | GroupxT1 | 0.27 | 0.712 | 0.06 |

| Control | 15.96 | 16.07 | 15.68 | GroupxT2 | 0.41 | 0.611 | 0.09 |

| Positive Affect (0–18) | |||||||

| Experimental | 15.07 | 15.40 | 15.28 | GroupxT1 | 1.31 | 0.028 * | 0.38 |

| Control | 15.07 | 14.09 | 13.93 | GroupxT2 | 1.34 | 0.042 * | 0.39 |

| Negative Affect (0–9) | |||||||

| Experimental | 6.15 | 6.67 | 6.38 | GroupxT1 | 0.29 | 0.398 | 0.12 |

| Control | 6.15 | 6.38 | 6.76 | GroupxT2 | −0.38 | 0.371 | −0.15 |

| Restless Tense Behavior (0–9) | |||||||

| Experimental | 5.02 | 5.47 | 5.01 | GroupxT1 | 0.48 | 0.341 | 0.19 |

| Control | 5.02 | 4.99 | 5.29 | GroupxT2 | −0.28 | 0.516 | −0.11 |

| Positive Self-Esteem (0–9) | |||||||

| Experimental | 6.93 | 7.39 | 7.24 | GroupxT1 | 0.12 | 0.693 | 0.06 |

| Control | 6.93 | 7.27 | 7.16 | GroupxT2 | 0.09 | 0.821 | 0.04 |

| Social Relationships (0–18) | |||||||

| Experimental | 10.50 | 11.13 | 10.31 | GroupxT1 | 0.83 | 0.139 | 0.32 |

| Control | 10.50 | 10.30 | 9.78 | GroupxT2 | 0.53 | 0.246 | 0.21 |

| Social Isolation (0–9) | |||||||

| Experimental | 5.78 | 6.29 | 6.16 | GroupxT1 | 0.53 | 0.091 | 0.24 |

| Control | 5.78 | 5.76 | 5.70 | GroupxT2 | 0.46 | 0.300 | 0.20 |

| Feeling at Home (0–12) | |||||||

| Experimental | 8.59 | 8.45 | 8.64 | GroupxT1 | 0.06 | 0.906 | 0.02 |

| Control | 8.59 | 8.40 | 8.39 | GroupxT2 | 0.25 | 0.612 | 0.08 |

| Having Something to Do (0–6) | |||||||

| Experimental | 2.70 | 2.90 | 3.04 | GroupxT1 | 0.17 | 0.572 | 0.10 |

| Control | 2.70 | 2.73 | 2.54 | GroupxT2 | 0.50 | 0.131 | 0.30 |

| NPI-Q (10) total (range: 0–30) | |||||||

| Experimental | 4.22 | 4.15 | 4.13 | GroupxT1 | 0.71 | 0.341 | 0.18 |

| Control | 4.22 | 3.44 | 3.51 | GroupxT2 | 0.62 | 0.495 | 0.15 |

| Short Sense of Competence total (range: 7–35) | |||||||

| Experimental | 29.51 | 29.28 | 29.62 | GroupxT1 | −1.00 | 0.227 | −0.19 |

| Control | 29.51 | 30.28 | 30.60 | GroupxT2 | −0.98 | 0.251 | −0.19 |

| Questions for Resident | |||||||

| Regarding feeling known as a person (range: 1–10) | |||||||

| Experimental | 7.69 | 8.27 | 8.05 | GroupxT1 | 0.50 | 0.213 | 0.21 |

| Control | 7.69 | 7.77 | 7.83 | GroupxT2 | 0.22 | 0.611 | 0.09 |

| Regarding feeling satisfied with nursing home care (range: 1–10) | |||||||

| Experimental | 7.51 | 7.70 | 7.30 | GroupxT1 | −0.04 | 0.918 | −0.02 |

| Control | 7.51 | 7.74 | 7.23 | GroupxT2 | 0.07 | 0.840 | 0.03 |

| Questions for Informal Carer | |||||||

| Regarding feeling known as the informal carer (range: 1–10) | |||||||

| Experimental | 8.60 | 8.74 | 8.59 | GroupxT1 | 0.28 | 0.168 | 0.19 |

| Control | 8.60 | 8.46 | 8.51 | GroupxT2 | 0.07 | 0.731 | 0.05 |

| Regarding feeling satisifed with loved one’s stay in nursing home (range: 1–10) | |||||||

| Experimental | 8.69 | 8.66 | 8.57 | GroupxT1 | 0.08 | 0.672 | 0.06 |

| Control | 8.69 | 8.58 | 8.37 | GroupxT2 | 0.19 | 0.464 | 0.15 |

| Regarding feeling that loved one is known in nursing home (range: 1–10) | |||||||

| Experimental | 8.79 | 8.75 | 8.64 | GroupxT1 | 0.25 | 0.276 | 0.19 |

| Control | 8.79 | 8.51 | 8.44 | GroupxT2 | 0.20 | 0.380 | 0.16 |

| Pre-Test (T0) | Post-Test (T1) | ANCOVA | Effect Size | |||||||||||

| Exp (n = 23) | Control (n = 28) | Experimental (n = 19) | Control (n = 22) | Experimental adjM (SE) | Control adjM (SE) | p | Partial Eta | |||||||

| Global Empathy IRI a (range: 0–112) | Baseline Total ADQ b | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | M | (SD) | Group | ||||

| Low | 67.14 | (9.03) | 57.79 | (7.15) | 64.83 | (4.31) | 59.73 | (7.32) | 61.67 (2.41) | 62.13 (1.55) | Total Baseline ADQ b | 0.851 | 0.001 | |

| High | 62.69 | (8.11) | 64.22 | (12.15) | 57.15 | (5.87) | 68.00 | (9.24) | 56.76 (1.57) | 66.32 (2.16) | Group xTotal Baseline ADQ b | 0.032 * | 0.121 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, J.R.O.; Ettema, T.P.; Hoogendoorn, A.W.; Boersma, P.; Sikkes, S.A.M.; Gobbens, R.J.J.; Dröes, R.-M. Effects of a Digital, Person-Centered, Photo-Activity Intervention on the Social Interaction of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia, Their Informal Carers and Formal Carers: An Explorative Randomized Controlled Trial. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081008

Tan JRO, Ettema TP, Hoogendoorn AW, Boersma P, Sikkes SAM, Gobbens RJJ, Dröes R-M. Effects of a Digital, Person-Centered, Photo-Activity Intervention on the Social Interaction of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia, Their Informal Carers and Formal Carers: An Explorative Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081008

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Josephine Rose Orejana, Teake P. Ettema, Adriaan W. Hoogendoorn, Petra Boersma, Sietske A. M. Sikkes, Robbert J. J. Gobbens, and Rose-Marie Dröes. 2025. "Effects of a Digital, Person-Centered, Photo-Activity Intervention on the Social Interaction of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia, Their Informal Carers and Formal Carers: An Explorative Randomized Controlled Trial" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081008

APA StyleTan, J. R. O., Ettema, T. P., Hoogendoorn, A. W., Boersma, P., Sikkes, S. A. M., Gobbens, R. J. J., & Dröes, R.-M. (2025). Effects of a Digital, Person-Centered, Photo-Activity Intervention on the Social Interaction of Nursing Home Residents with Dementia, Their Informal Carers and Formal Carers: An Explorative Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1008. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081008