The Dark Side of Employee’s Leadership Potential: Its Impact on Leader Jealousy and Ostracism

Abstract

1. Introduction

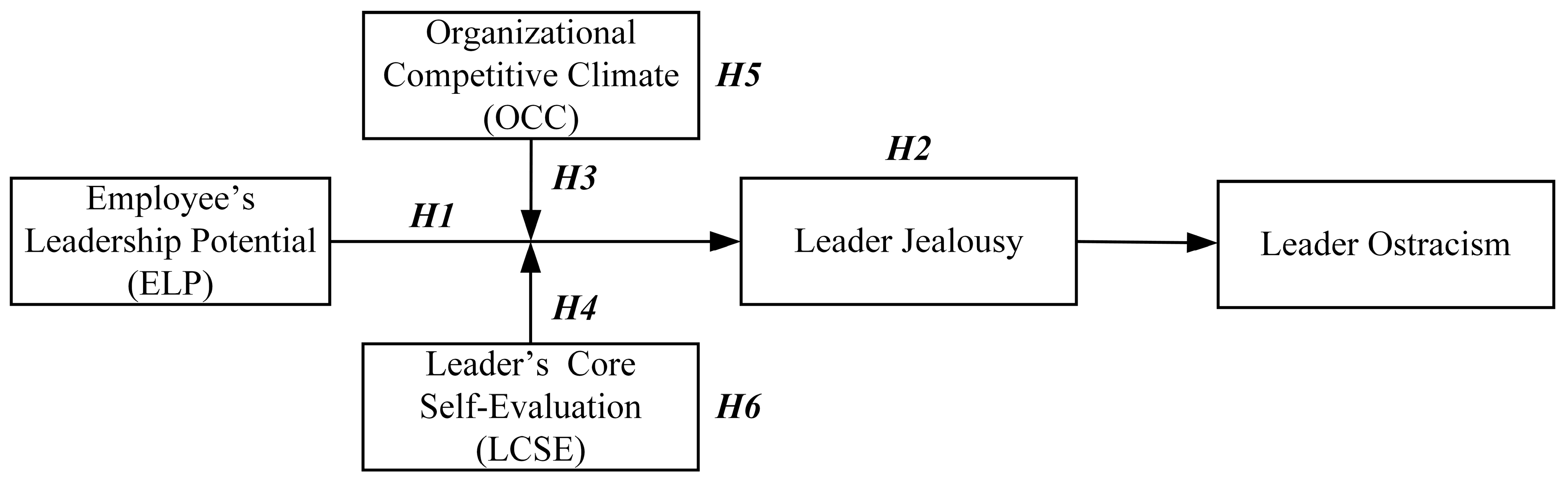

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypothesis

2.1. Social Comparison Theory

2.2. Employee’s Leadership Potential and Leader Jealousy

2.3. The Mediating Role of Leader Jealousy

2.4. The Moderating Role of Organizational Competitive Climate

2.5. The Moderating Role of Leader’s Core Self-Evaluation

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedures

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Biases

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Analysis

4.4. Hypotheses’ Tests

4.4.1. Mediating Effect Test

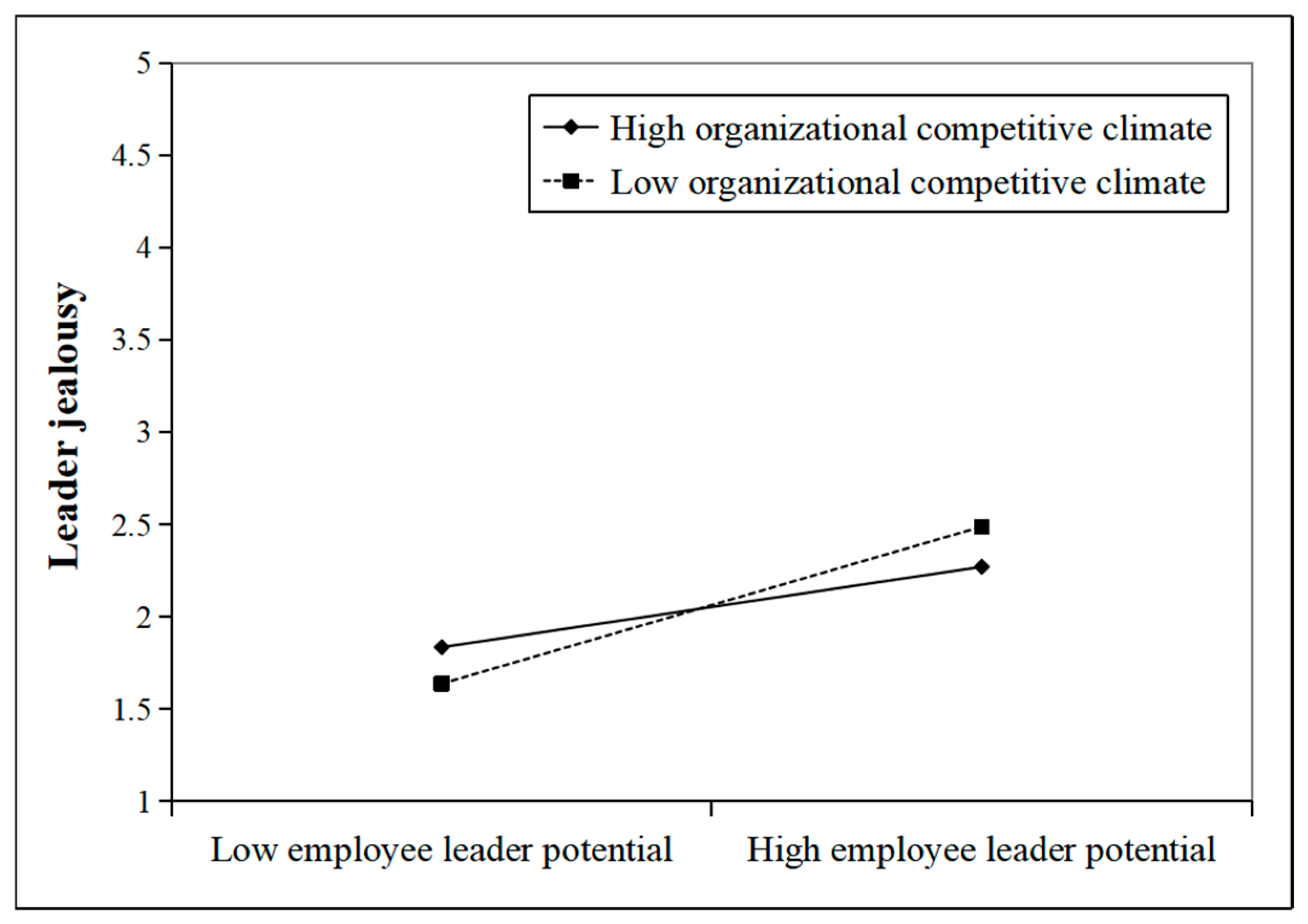

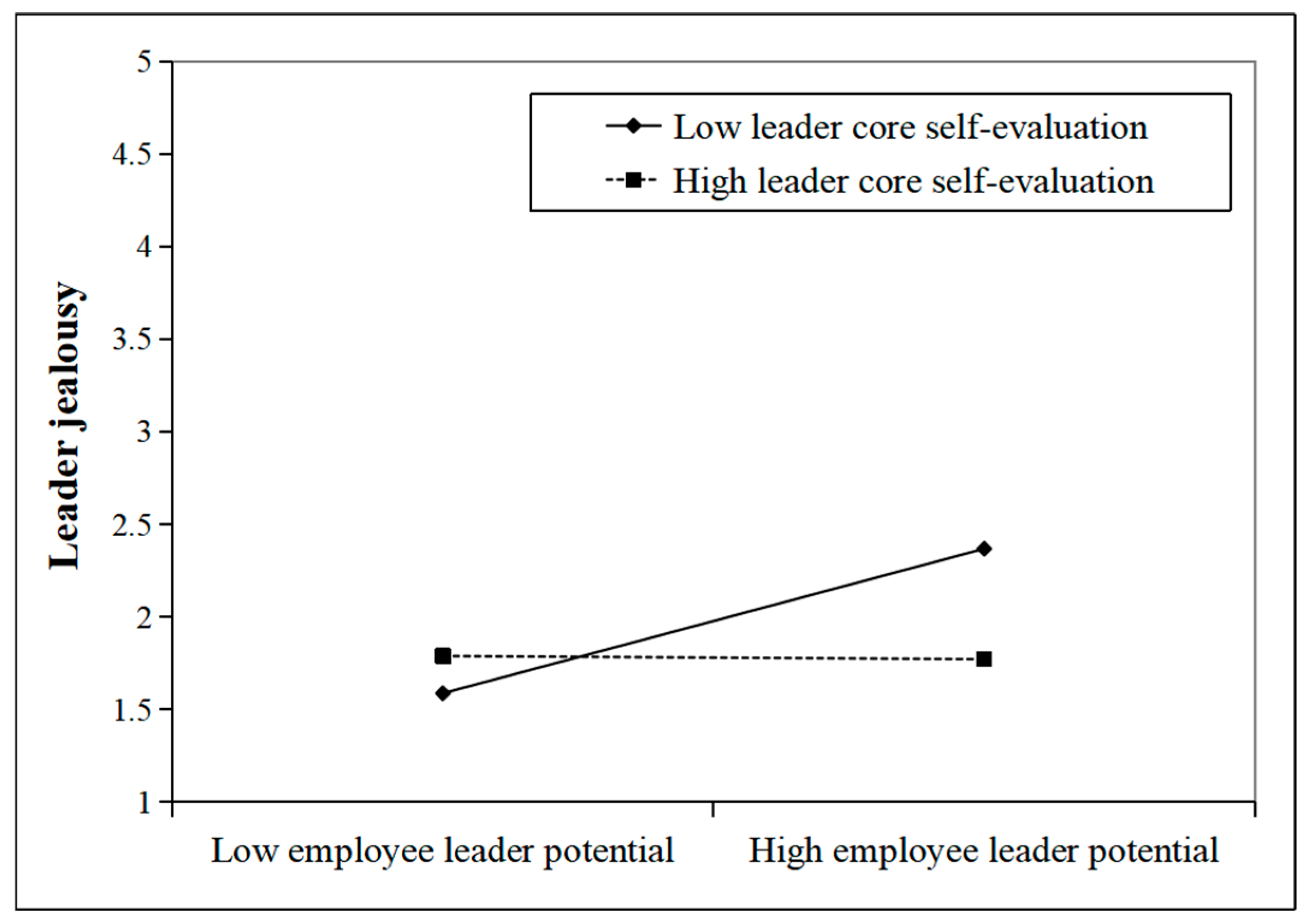

4.4.2. Moderating Effect Test

4.4.3. Moderated Mediating Effect Test

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahn, J., Lee, S., & Yun, S. (2018). Leaders’ core self-evaluation, ethical leadership, and employees’ job performance: The moderating role of employees’ exchange ideology. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Romeedy, B. S., Tekin Ozbek, O., Tarinc, A., Eren, R., & Alshiha, A. A. (2025). The effect of talent management on work engagement and organizational performance: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights. Forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anglin, A. H., Kincaid, P. A., Short, J. C., & Allen, D. G. (2022). Role theory perspectives: Past, present, and future applications of role theories in management research. Journal of Management, 48(6), 1469–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M. U., Haq, I. U., De Clercq, D., & Liu, C. (2024). Why and when do employees feel guilty about observing supervisor ostracism? The critical roles of observers’ silence behavior and leader–member exchange quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 194(2), 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bani-Melhem, S., Shamsudin, F. M., Abukhait, R., & Al-Hawari, M. A. (2023). Competitive psychological climate as a double-edged sword: A moderated mediation model of organization-based self-esteem, jealousy, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 54, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, A. R., Fatima, T., Imran, M. K., & Iqbal, K. (2021). Is it my fault and how will I react? A phenomenology of perceived causes and consequences of workplace ostracism. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 30(1), 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Core self-evaluations: A review of the trait and its role in job satisfaction and job performance. European Journal of Personality, 17(S1), S5–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S., Aydin, N., Frey, D., & Peus, C. (2018). Leader narcissism predicts malicious envy and supervisor-targeted counterproductive work behavior: Evidence from field and experimental research. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(3), 725–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. P., Cron, W. L., & Slocum, J. W., Jr. (1998). Effects of trait competitiveness and perceived intraorganizational competition on salesperson goal setting and performance. Journal of Marketing, 62(4), 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, F., Idug, Y., Uvet, H., Gligor, N., & Kayaalp, A. (2024). Social comparison theory: A review and future directions. Psychology & Marketing, 41(11), 2823–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnevale, J. B., Huang, L., Vincent, L. C., Yu, L., & He, W. (2024). Outshined by creative stars: A dual-pathway model of leader reactions to employees’ reputation for creativity. Journal of Management, 50(7), 2571–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. H., Ferris, D. L., Johnson, R. E., Rosen, C. C., & Tan, J. A. (2012). Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. Journal of Management, 38(1), 81–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, E. M., Kim, T. Y., Rodgers, M., & Chen, T. (2021). Helping while competing? The complex effects of competitive climates on the prosocial identity and performance relationship. Journal of Management Studies, 58(6), 1507–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D. V., Riggio, R. E., Tan, S. J., & Conger, J. A. (2021). Advancing the science of 21st-century leadership development: Theory, research, and practice. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(5), 101557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirkesen, S., & Tezel, A. (2022). Investigating major challenges for industry 4.0 adoption among construction companies. Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management, 29(3), 1470–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiLiello, T. C., & Houghton, J. D. (2006). Maximizing organizational leadership capacity for the future: Toward a model of self-leadership, innovation and creativity. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(4), 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, L., Oh, I. S., Vankatwyk, P., & Tesluk, P. E. (2011). Developing executive leaders: The relative contribution of cognitive ability, personality, and the accumulation of work experience in predicting strategic thinking competency. Personnel Psychology, 64(4), 829–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dries, N., & Pepermans, R. (2012). How to identify leadership potential: Development and testing of a consensus model. Human Resource Management, 51(3), 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, M. K., Scott, K. L., Shaw, J. D., Tepper, B. J., & Aquino, K. (2012). A social context model of envy and social undermining. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 643–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N. T. (2015). Analyzing relative deprivation in relation to deservingness, entitlement and resentment. Social Justice Research, 28, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, D. P., Ryan, M. K., & Begeny, C. T. (2023). Support (and rejection) of meritocracy as a self-enhancement identity strategy: A qualitative study of university students’ perceptions about meritocracy in higher education. European Journal of Social Psychology, 53(4), 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferris, D. L., Brown, D. J., Berry, J. W., & Lian, H. (2008). The development and validation of the Workplace Ostracism Scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferris, D. L., Lian, H., Brown, D. J., & Morrison, R. (2015). Ostracism, self-esteem, and job performance: When do we self-verify and when do we self-enhance? Academy of Management Journal, 58(1), 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T. D., Major, D. A., & Davis, D. D. (2008). The interactive relationship of competitive climate and trait competitiveness with workplace attitudes, stress, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(7), 899–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fousiani, K., & Wisse, B. (2022). Effects of leaders’ power construal on leader-member exchange: The moderating role of competitive climate at work. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 29(3), 306–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. G. (2020). The importance of being resilient: Psychological well-being, job autonomy, and self-esteem of organization managers. Personality and Individual Differences, 155, 109731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddes, D., Callister, R. R., & Gibson, D. E. (2020). A message in the madness: Functions of workplace anger in organizational life. Academy of Management Perspectives, 34(1), 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpott, F. H., & Van Quaquebeke, N. (2023). Kiss-up-kick-down to get ahead: A resource perspective on how, when, why, and with whom middle managers use ingratiatory and exploitative behaviours to advance their careers. Journal of Management Studies, 60(7), 1855–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamrawi, N., Shal, T., & Ghamrawi, N. A. (2024). Exploring the impact of AI on teacher leadership: Regressing or expanding? Education and Information Technologies, 29(7), 8415–8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giessner, S. R., & Schubert, T. W. (2007). High in the hierarchy: How vertical location and judgments of leaders’ power are interrelated. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 104(1), 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, L. M., & Sarkis, J. (2018). The role of employees’ leadership perceptions, values, and motivation in employees’ provenvironmental behaviors. Journal of Cleaner Production, 196, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J., Ashton-James, C. E., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2007). Social comparison processes in organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1), 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groves, K. S., & Feyerherm, A. E. (2022). Developing a leadership potential model for the new era of work and organizations. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 43(6), 978–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M., Liu, S., Chu, F., Ye, L., & Zhang, Q. (2019). Supervisory and coworker support for safety: Buffers between job insecurity and safety performance of high-speed railway drivers in China. Safety Science, 117, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsch, K., & Festing, M. (2020). Dynamic talent management capabilities and organizational agility—A qualitative exploration. Human Resource Management, 59(1), 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henle, C. A., Shore, L. M., Morton, J. W., & Conroy, S. A. (2023). Putting a spotlight on the ostracizer: Intentional workplace ostracism motives. Group & Organization Management, 48(4), 1014–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. C., Cogswell, J. E., & Smith, M. B. (2020). The antecedents and outcomes of workplace ostracism: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(6), 577–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J., Wang, Z., Liden, R. C., & Sun, J. (2012). The influence of leader core self-evaluation on follower reports of transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 23(5), 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iles, P. (1997). Sustainable high-potential career development: A resource-based view. Career Development International, 2(7), 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, O. S., & Chaker, N. N. (2022). Harnessing the power within: The consequences of salesperson moral identity and the moderating role of internal competitive climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 181(4), 847–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, D., & Han, H. (2013). Personality, social comparison, consumption emotions, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: How do these and other factors relate in a hotel setting? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(7), 970–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, I. M., Bilal, A. R., Fatima, T., & Mohammed, Z. J. (2021). Does organizational cronyism undermine social capital? Testing the mediating role of workplace ostracism and the moderating role of workplace incivility. Career Development International, 26(5), 657–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B. K., Jeung, C. W., & Yoon, H. J. (2010). Investigating the influences of core self-evaluations, job autonomy, and intrinsic motivation on in-role job performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(4), 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(3), 693–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 303–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., & Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(1), 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Judge, T. A., & Scott, B. A. (2009). The role of core self-evaluations in the coping process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(1), 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanat-Maymon, Y., Elimelech, M., & Roth, G. (2020). Work motivations as antecedents and outcomes of leadership: Integrating self-determination theory and the full range leadership theory. European Management Journal, 38(4), 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kets de Vries, M. F. (1994). The leadership mystique. Academy of Management Perspectives, 8(3), 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. K., Quratulain, S., & Bell, C. M. (2014). Episodic envy and counterproductive work behaviors: Is more justice always good? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(1), 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E., & Glomb, T. M. (2014). Victimization of high performers: The roles of envy and work group identification. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H., & Jang, E. (2023). Workplace ostracism effects on employees’ negative health outcomes: Focusing on the mediating role of envy. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konieczna, A. (2024). “Zero interaction”, ignoring and acts of omission in the school ecology: Peer ostracism from the perspective of involved adolescents. Social Psychology of Education, 27, 3203–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossyva, D., Theriou, G., Aggelidis, V., & Sarigiannidis, L. (2024). Retaining talent in knowledge-intensive services: Enhancing employee engagement through human resource, knowledge and change management. Journal of Knowledge Management, 28(2), 409–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotlyar, I., Karakowsky, L., Jo Ducharme, M., & Boekhorst, J. A. (2014). Do “rising stars” avoid risk?: Status-based labels and decision making. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 35(2), 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, C. K., Van der Vegt, G. S., Walter, F., & Huang, X. (2011). Harming high performers: A social comparison perspective on interpersonal harming in work teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A., Schwarz, G., Reh, S., Li, Z., Zheng, Y., Liu, J., & Gopalan, N. (2025). Upward leader-member exchange social comparison and organizational citizenship behaviour: The mediating role of interpersonal justice and moderating role of competitive climate. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 34(1), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Zhang, S., Mo, S., & Newman, A. (2024). Relative leader-member exchange and unethical pro-leader behavior: The role of envy and distributive justice climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 192(1), 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M., Xu, X., & Kwan, H. K. (2023). The antecedents and consequences of workplace envy: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 40(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Gao, X., Liu, Z., & Gao, J. (2021). When self-threat leads to the selection of emotion-enhancing options: The role of perceived transience of emotion. European Journal of Marketing, 55(11), 2945–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Peng, Y., Xu, S., & Azeem, M. U. (2024). Proactive employees perceive coworker ostracism: The moderating effect of team envy and the behavioral outcome of production deviance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 29(6), 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D., Liao, H., & Loi, R. (2012). The dark side of leadership: A three-level investigation of the cascading effect of abusive supervision on employee creativity. Academy of Management Journal, 55(5), 1187–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Geng, J., & Yao, P. (2021). Relationship of leadership and envy: How to resolve workplace envy with leadership—A bibliometric review study. Journal of Intelligence, 9(3), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luria, G., & Berson, Y. (2013). How do leadership motives affect informal and formal leadership emergence? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(7), 995–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marescaux, E., De Winne, S., & Brebels, L. (2021). Putting the pieces together: A review of HR differentiation literature and a multilevel model. Journal of Management, 47(6), 1564–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, M. J., & Kelemen, T. K. (2025). To compare is human: A review of social comparison theory in organizational settings. Journal of Management, 51(1), 212–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, A., & Johnson, B. K. (2022). Social comparison and envy on social media: A critical review. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G., McMurray, A. J., Manoharan, A., & Rajesh, J. I. (2024). Workplace and workplace leader arrogance: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Management Reviews, 26(4), 608–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Shamsudin, F., Bani-Melhem, S., Abukhait, R., Aboelmaged, M., & Pillai, R. (2024). Favouritism: A recipe for ostracism? How jealousy and self-esteem intervene. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 45(1), 116–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morf, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2024). Ups and downs in transformational leadership: A weekly diary study. European Management Journal, 42(2), 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, J. S., Goncalo, J. A., & Kamdar, D. (2011). Recognizing creative leadership: Can creative idea expression negatively relate to perceptions of leadership potential? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47(2), 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtza, M. H., & Rasheed, M. I. (2023). The dark side of competitive psychological climate: Exploring the role of workplace envy. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 6(3), 1400–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W. (2017). Can idiosyncratic deals promote perceptions of competitive climate, felt ostracism, and turnover? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. W., Shao, Y., Koopmann, J., Wang, M., Hsu, D. Y., & Yim, F. H. (2022). The effects of idea rejection on creative self-efficacy and idea generation: Intention to remain and perceived innovation importance as moderators. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 43(1), 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oedzes, J. J., Van der Vegt, G. S., Rink, F. A., & Walter, F. (2019). On the origins of informal hierarchy: The interactive role of formal leadership and task complexity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(3), 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, S. A., & Mahmood, N. H. N. (2022). Linking level of engagement, HR practices and employee performance among high-potential employees in Malaysian manufacturing sector. Global Business Review, 23(3), 641–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J., Zheng, X., Xu, H., Li, J., & Lam, C. K. (2021). What if my coworker builds a better LMX? The roles of envy and coworker pride for the relationships of LMX social comparison with learning and undermining. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(9), 1144–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. G., Low, C. M., Walker, A. R., & Gamm, B. K. (2005). Friendship jealousy in young adolescents: Individual differences and links to sex, self-esteem, aggression, and social adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 41(1), 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrmann-Graham, J., Liu, J., Cangioni, C., & Spataro, S. E. (2022). Fostering psychological safety: Using improvisation as a team building tool in management education. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfundmair, M., Wood, N. R., Hales, A., & Wesselmann, E. D. (2024). How social exclusion makes radicalism flourish: A review of empirical evidence. Journal of Social Issues, 80(1), 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaprasad, B. S., Rao, S., Rao, N., Prabhu, D., & Kumar, M. S. (2022). Linking hospitality and tourism students’ internship satisfaction to career decision self-efficacy: A moderated-mediation analysis involving career development constructs. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 30, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, B., St-Onge, S., & Ullah, S. (2023). Abusive supervision and deviance behaviors in the hospitality industry: The role of intrinsic motivation and core self-evaluation. Tourism Management, 98, 104748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reh, S., Tröster, C., & Van Quaquebeke, N. (2018). Keeping (future) rivals down: Temporal social comparison predicts coworker social undermining via future status threat and envy. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(4), 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reh, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., Tröster, C., & Giessner, S. R. (2022). When and why does status threat at work bring out the best and the worst in us? A temporal social comparison theory. Organizational Psychology Review, 12(3), 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, D., Wesselmann, E. D., & Williams, K. D. (2018). Hurt people hurt people: Ostracism and aggression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 762–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaubroeck, J., & Lam, S. S. (2004). Comparing lots before and after: Promotion rejectees’ invidious reactions to promotees. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 94(1), 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N., & Dhar, R. L. (2022). From curse to cure of workplace ostracism: A systematic review and future research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 32(3), 100836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, Z., Heavey, C., & Veiga, J. J. F. (2010). The impact of CEO core self-evaluation on the firm’s entrepreneurial orientation. Strategic Management Journal, 31(1), 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. H., & Kim, S. H. (2007). Comprehending envy. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steffens, N. K., Fonseca, M. A., Ryan, M. K., Rink, F. A., Stoker, J. I., & Pieterse, A. N. (2018). How feedback about leadership potential impacts ambition, organizational commitment, and performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(6), 637–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Gao, F., & Avolio, B. J. (2023). Do core self-evaluations mitigate or exacerbate the self-regulation depletion effect of leader injustice? The role of leader-contingent self-esteem. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 96(4), 919–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, K., Narayanan, J., & McAllister, D. J. (2012). Envy as pain: Rethinking the nature of envy and its implications for employees and organizations. Academy of Management Review, 37(1), 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troth, A. C., & Gyetvey, C. (2014). Identifying leadership potential in an A ustralian context. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52(3), 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zelderen, A., Dries, N., & Marescaux, E. (2023). Talents Under Threat: The Anticipation of Being Ostracized by Non-Talents Drives Talent Turnover. Group & Organization Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, R. P. (2000). Negative emotion in the workplace: Employee jealousy and envy. International Journal of Stress Management, 7(3), 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, F., Humphrey, R. H., & Cole, M. S. (2012). Unleashing leadership potential:: Toward an evidence-based management of emotional intelligence. Organizational Dynamics, 41(3), 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. D., & Sung, W. C. (2016). Predictors of organizational citizenship behavior: Ethical leadership and workplace jealousy. Journal of Business Ethics, 135, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M. A., Donaldson, S. I., Lee, J. Y., & Donaldson, S. I. (2019). Reinvigorating research on gender in the workplace using a positive work and organizations perspective. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(4), 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, T. (2021). Workplace interpersonal capitalization: Employee reactions to coworker positive event disclosures. Academy of Management Journal, 64(2), 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, R. (1997). Harmony and patriarchy: The cultural basis for ‘paternalistic headship’ among the overseas Chinese. Organization Studies, 18(3), 445–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, K. A., & Kuiper, N. A. (1997). Individual differences in the experience of emotions. Clinical Psychology Review, 17(7), 791–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisse, B., Rus, D., Keller, A. C., & Sleebos, E. (2019). “Fear of losing power corrupts those who wield it”: The combined effects of leader fear of losing power and competitive climate on leader self-serving behavior. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(6), 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J. V. (1989). Theory and research concerning social comparisons of personal attributes. Psychological Bulletin, 106(2), 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X. Y., Wei, J., Hu, Q., & Liao, Z. (2023). Is the door really open? A contingent model of boundary spanning behavior and abusive supervisory behavior. Journal of Business Research, 169, 114284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, E., Huang, X., & Robinson, S. L. (2017). When self-view is at stake: Responses to ostracism through the lens of self-verification theory. Journal of Management, 43(7), 2281–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y., Li, X., Wang, H., & Zhang, Q. (2020). How employee’s leadership potential leads to leadership ostracism behavior: The mediating role of envy, and the moderating role of political skills. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L. R., Huang, C. F., & Wu, K. S. (2011). The association among project manager’s leadership style, teamwork and project success. International Journal of Project Management, 29(3), 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S., Üngüren, E., Tekin, Ö. A., & Derman, E. (2023). Exploring the interplay of competition and justice: A moderated mediation model of competitive psychological climate, workplace envy, interpersonal citizenship behavior, and organizational justice. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L., Duffy, M. K., & Tepper, B. J. (2018). Consequences of downward envy: A model of self-esteem threat, abusive supervision, and supervisory leader self-improvement. Academy of Management Journal, 61(6), 2296–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. (2025). Unity or individualism? The “double-edged sword” effect of team leader bottom-line mentality in multi-team context. Current Psychology, 44, 4439–4450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Factors | χ2/df | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model | ELP; OCC; LCSE; LJ; LO | 3.566 | 1408.571 | 395 | 0.926 | 0.918 | 0.048 | 0.062 |

| Four-factor model | ELP + OCC; LCSE; LJ; LO | 7.767 | 3098.919 | 399 | 0.803 | 0.785 | 0.105 | 0.100 |

| Three-factor model | ELP + OCC + LCSE; LJ; LO | 11.075 | 4452.164 | 402 | 0.704 | 0.680 | 0.107 | 0.122 |

| Two-factor model | ELP + OCC + LCSE + LJ; LO | 15.756 | 6365.468 | 404 | 0.565 | 0.531 | 0.128 | 0.148 |

| One-factor model | ELP + OCC + LCSE + LJ + LO | 28.330 | 12,210.229 | 431 | 0.140 | 0.132 | 0.304 | 0.202 |

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1.14 | 0.35 | ||||||||

| 2. Education | 2.83 | 0.53 | 0.05 | |||||||

| 3. Age | 2.93 | 0.79 | −0.01 | −0.32 ** | ||||||

| 4. Tenure | 3.35 | 0.91 | −0.07 | −0.23 ** | 0.69 ** | |||||

| 5. ELP | 2.12 | 0.76 | 0.12 ** | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.09 * | ||||

| 6. Leader jealousy | 1.77 | 0.96 | 0.09 * | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.12 ** | 0.35 ** | |||

| 7. OCC | 1.96 | 0.63 | 0.08 * | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.04 | 0.14 ** | 0.04 | ||

| 8. LCSE | 3.98 | 0.50 | −0.13 ** | −0.03 | 0.10 ** | 0.12 ** | −0.38 ** | −0.34 ** | −0.34 ** | |

| 9. Leader ostracism | 2.63 | 0.88 | 0.05 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.06 | 0.37 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.11 ** | −0.43 ** |

| Variable | Leader Jealousy | Leader Ostracism | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Gender | 0.076 * | 0.038 | 0.040 | −0.001 | −0.015 |

| Education | −0.047 | −0.039 | 0.008 | 0.017 | 0.031 |

| Age | 0.138 * | 0.098 | 0.063 | 0.018 | −0.018 |

| Tenure | −0.219 ** | −0.160 ** | −0.096 | −0.032 | 0.027 |

| ELP | 0.333 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.240 ** | ||

| Leader jealousy | 0.368 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.035 | 0.142 | 0.007 | 0.134 | 0.243 |

| F | 5.963 ** | 21.966 ** | 1.170 | 20.618 ** | 36.951 ** |

| Pathway | Effect | SE | t | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||||

| Total effect | 0.420 | 0.043 | 9.886 | 0.337 | 0.504 |

| Direct effect | 0.278 | 0.042 | 6.629 | 0.196 | 0.361 |

| ELP → Leader jealousy → Leader ostracism | 0.142 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.083 | 0.209 |

| Variable | Leader Jealousy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

| Gender | 0.076 | 0.039 | 0.087 | 0.020 | −0.021 |

| Education | −0.047 | −0.039 | −0.072 | −0.041 | −0.033 |

| Age | 0.138 * | 0.097 | 0.121 | 0.116 * | 0.171 * |

| Tenure | −0.219 * | −0.161 ** | −0.166 ** | −0.154 * | −0.172 ** |

| ELP | 0.334 ** | 0.423 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.251 ** | |

| OCC | −0.013 | 0.008 | |||

| ELP × OCC | 0.217 ** | ||||

| LCSE | −0.234 ** | ||||

| ELP × LCSE | −0.527 ** | ||||

| R2 | 0.035 | 0.142 | 0.152 | 0.188 | 0.278 |

| F | 5.963 ** | 18.327 ** | 17.017 ** | 25.646 ** | 36.519 ** |

| Path | Mediator | Moderated Mediation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator | Effect | SE | 95% CI | Index | (CI) | |

| ELP → Leader jealousy → Leader ostracism | Low OCC (M − 1SD) | 0.096 | 0.037 | [0.023, 0.166] | 0.073 | [0.006, 0.160] |

| High OCC (M + 1SD) | 0.188 | 0.042 | [0.083, 0.203] | |||

| Difference group | 0.092 | 0.049 | [0.007, 0.201] | |||

| Low LCSE (M − 1SD) | 0.173 | 0.030 | [0.118, 0.232] | −0.177 | [−0.242, −0.121] | |

| High LCSE (M + 1SD) | −0.004 | 0.025 | [−0.055, 0.044] | |||

| Difference group | −0.177 | 0.031 | [−0.241, −0.121] | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Z.; Wang, F.; Ye, L.; Liao, G.; Zhang, Q. The Dark Side of Employee’s Leadership Potential: Its Impact on Leader Jealousy and Ostracism. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081001

Yu Z, Wang F, Ye L, Liao G, Zhang Q. The Dark Side of Employee’s Leadership Potential: Its Impact on Leader Jealousy and Ostracism. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081001

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Zhen, Feiwen Wang, Long Ye, Ganli Liao, and Qichao Zhang. 2025. "The Dark Side of Employee’s Leadership Potential: Its Impact on Leader Jealousy and Ostracism" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 8: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081001

APA StyleYu, Z., Wang, F., Ye, L., Liao, G., & Zhang, Q. (2025). The Dark Side of Employee’s Leadership Potential: Its Impact on Leader Jealousy and Ostracism. Behavioral Sciences, 15(8), 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15081001