Public Sports Facility Availability in Living Communities and Mental Health of Older People in China: The Mediating Effect of Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Public Sports Facility Availability in Living Communities and Older People’s Mental Health

2.2. The Mediating Roles of Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Age, Income, Education, and Regional Economic Development

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Explained Variable

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.2.4. Mediating Variable

3.3. Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Benchmark Regression and Endogeneity Test

4.3. Robustness Checks

4.3.1. Changing the Sample Size

4.3.2. Subgroup Robustness Check

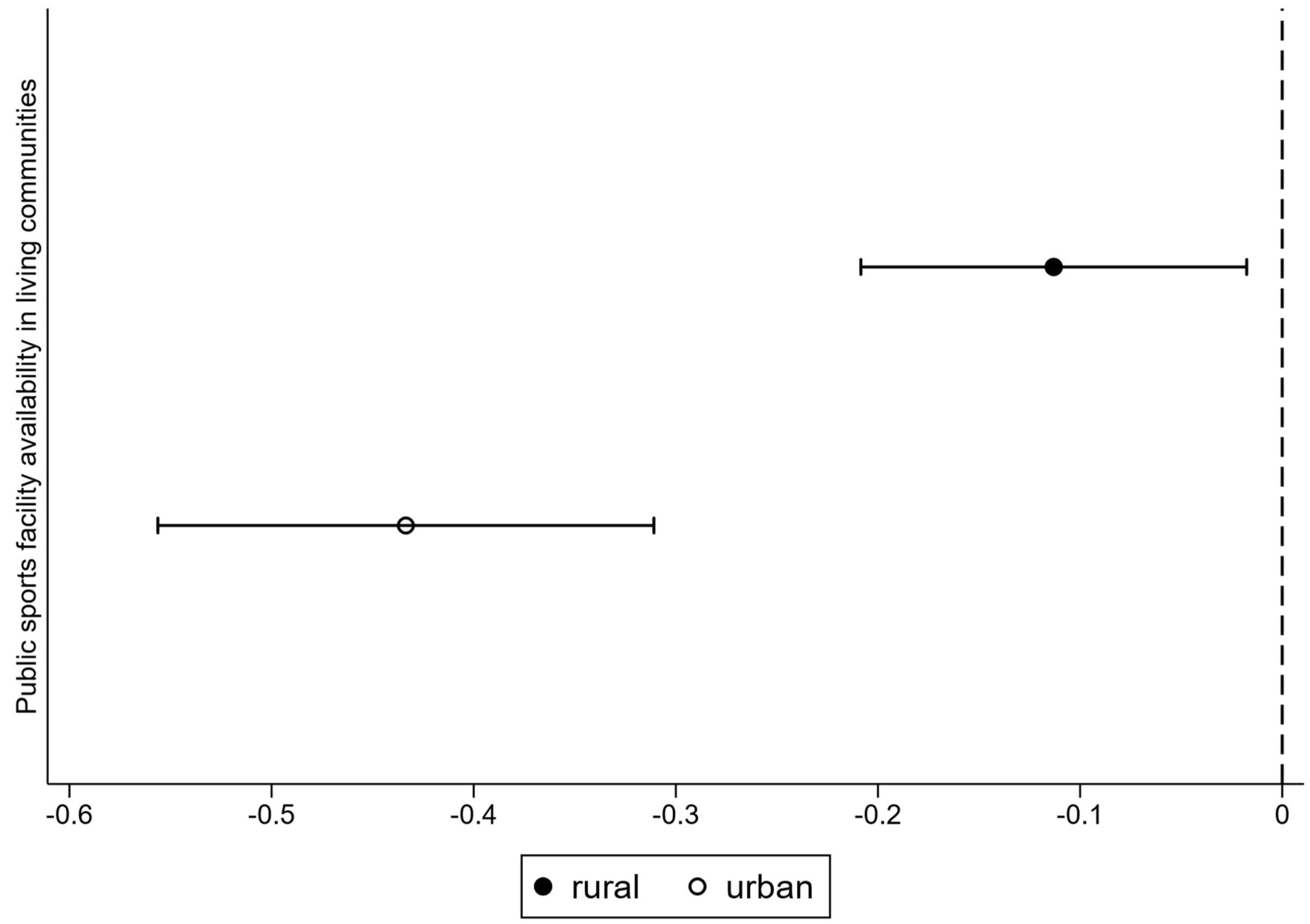

4.3.3. Urban–Rural Heterogeneous Effect Analysis

4.4. Exploring the Mediating Roles of Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction

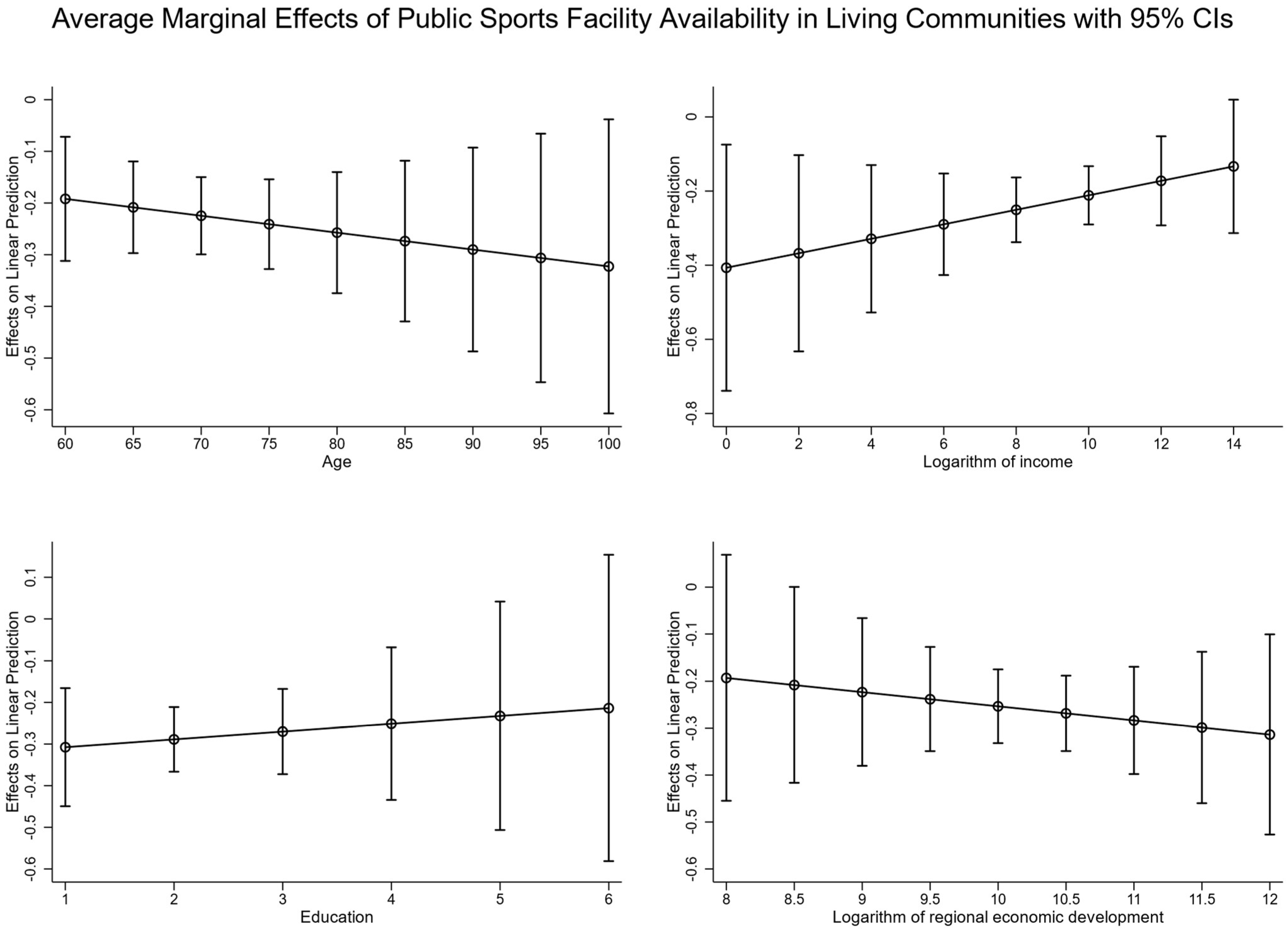

4.5. Exploring the Moderating Effect of Age, Income, Education, and Regional Economic Development

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Description of the Assignment |

|---|---|

| Do you feel in a good mood? | “No” = 2; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 0 |

| Do you feel lonely? | “No” = 0; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 2 |

| Do you feel sad? | “No” = 0; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 2 |

| Do you feel like you are having a good time? | “No” = 2; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 0 |

| Don’t you feel like eating? | “No” = 0; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 2 |

| Are you having trouble sleeping? | “No” = 0; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 2 |

| Do you think you’re out of practice? | “No” = 0; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 2 |

| Do you feel you have nothing to do? | “No” = 0; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 2 |

| Do you find a lot of joy in life? | “No” = 2; “Sometimes” = 1; “Often” = 0 |

| 1 | The RDLS for each region is derived from the disparity between maximum and minimum altitudes, terrain flatness, and the comprehensive area of the landform. Utilizing ArcGIS software and China’s 1:1,000,000 scale geographic digital elevation simulation dataset, this study extracts raster data at a spatial resolution of 1 km × 1 km and subsequently calculates the provincial-level RDLS. |

References

- Addy, C. L., Wilson, D. K., Kirtland, K. A., Ainsworth, B. E., Sharpe, P., & Kimsey, D. (2004). Associations of perceived social and physical environmental supports with physical activity and walking behavior. American Journal of Public Health, 94(3), 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfons, A., Ateş, N. Y., & Groenen, P. J. F. (2022). A robust bootstrap test for mediation analysis. Organizational Research Methods, 25(3), 591–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreff, W. (2001). The correlation between economic underdevelopment and sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 1(4), 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R., Montgomery, A., Rojas, G., Fritsch, R., Solis, J., Signorelli, A., & Lewis, G. (2007). Common mental disorders and the built environment in Santiago, Chile. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(5), 394–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, G. F., & Riddell, W. C. (2019). Ageing and skills: The case of literacy skills. European Journal of Education, 54(1), 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, T. R. B., Borges, L. J., Petroski, E. L., & Gonçalves, L. H. T. (2008). Physical activity and mental health status among elderly people. Revista de Saúde Pública, 42, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berke, E. M., Gottlieb, L. M., Moudon, A. V., & Larson, E. B. (2007). Protective association between neighborhood walkability and depression in older men. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(4), 526–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R. W. (1997). Comfortable and maximum walking speed of adults aged 20–79 years: Reference values and determinants. Age and Ageing, 26(1), 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R. W., & Andrews, A. W. (2011). Normal walking speed: A descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy, 97(3), 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschmann, E. E., & Brady, S. A. (2013). Travel behaviors, sustainable mobility, and transit-oriented developments: A travel counts analysis of older adults in the Denver, Colorado metropolitan area. Journal of Transport Geography, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, I., & Gunnell, D. (2006). Suicide rates, life satisfaction and happiness as markers for population mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burillo, P., Barajas, Á., Gallardo, L., & García-Tascón, M. (2011). The influence of economic factors in urban sports facility planning: A study on Spanish regions. European Planning Studies, 19(10), 1755–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Hicks, A., & While, A. E. (2012). Depression and related factors in older people in China: A systematic review. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 22(1), 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmas, C., & Andersen, R. A. (2000). Exercise and older patients: Guidelines for the clinician. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(3), 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domenech-Abella, J., Mundo, J., Leonardi, M., Chatterji, S., Tobiasz-Adamczyk, B., Koskinen, S., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., Haro, J. M., & Olaya, B. (2020). Loneliness and depression among older European adults: The role of perceived neighborhood built environment. Health & Place, 62, 102280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., Cramm, J. M., Jin, C., Twisk, J., & Nieboer, A. P. (2020). The longitudinal relationship between income and social participation among Chinese older people. SSM-Population Health, 11, 100636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friis, K., Lasgaard, M., Rowlands, G., Osborne, R. H., & Maindal, H. T. (2016). Health literacy mediates the relationship between educational attainment and health behavior: A Danish population-based study. Journal of Health Communication, 21(sup2), 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C. Y., & Li, J. (2024). China development report on ageing (2024): Mental health status of older adults in China. Social Science Academic Press (China). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W., Feng, W., Xu, Q., Lu, S., & Cao, K. (2022). Barriers associated with the public use of sports facilities in China: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Administration of Sport of China. (2015). Zhejiang provincial sports bureau information release. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/n14471/n14482/n14519/c690393/content.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- General Administration of Sport of China. (2023). 2023 National sports venue statistics survey data. Available online: https://www.sport.gov.cn/gdnps/content.jsp?id=27549759 (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Gong, Y., Palmer, S., Gallacher, J., Marsden, T., & Fone, D. (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between objective measurements of the urban environment and psychological distress. Environment International, 96, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausdorff, J. M., Rios, D. A., & Edelberg, H. K. (2001). Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: A 1-year prospective study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82(8), 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, B., Kelley, J., & Wearing, A. (1993). Dimensions of mental health: Life satisfaction, positive affect, anxiety and depression. Social Indicators Research, 29, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himann, J. E., Cunningham, D. A., Rechnitzer, P. A., & Paterson, D. H. (1988). Age-related changes in speed of walking. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 20(2), 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, D. H., Sentell, T., & Gazmararian, J. A. (2006). Impact of health literacy on socioeconomic and racial differences in health in an elderly population. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, 857–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huebner, E. S., Suldo, S. M., & Gilman, R. (2006). Life Satisfaction. In G. G. Bear, & K. M. Minke (Eds.), Children’s needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention (pp. 357–368). National Association of School Psychologists. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y., & Yang, F. (2022). Association between internet use and successful aging of older Chinese women: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandola, A., Ashdown-Franks, G., Hendrikse, J., Sabiston, C. M., & Stubbs, B. (2019). Physical activity and depression: Towards understanding the antidepressant mechanisms of physical activity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 107, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. G., & Dingwell, J. B. (2008). Separating the effects of age and walking speed on gait variability. Gait & Posture, 27(4), 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., & Kosma, M. (2013). Psychosocial and environmental correlates of physical activity among Korean older adults. Research on Aging, 35(6), 750–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancet Global Mental Health Group. (2007). Scale up services for mental disorders: A call for action. The Lancet, 370(9594), 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. A., Ju, Y. J., Lee, J. E., Hyun, I. S., Nam, J. Y., Han, K. T., & Park, E. C. (2016). The relationship between sports facility accessibility and physical activity among Korean adults. BMC Public Health, 16, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. (1991). The production of space. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T., Wang, Q., Tan, Z., Zuo, W., & Wu, R. (2024). Neighborhood social environment and mental health of older adults in China: The mediating role of subjective well-being and the moderating role of green space. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1502020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Byles, J. E., Xu, X., Zhang, M., Wu, X., & Hall, J. J. (2017). Evaluation of successful aging among older people in China: Results from China health and retirement longitudinal study. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 17(8), 1183–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, S., Després, C., & Ramadier, T. (2011). When mobility makes sense: A qualitative and longitudinal study of the daily mobility of the elderly. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(1), 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M. S., Chui, E. W. T., & Li, L. W. (2020). The longitudinal associations between physical health and mental health among older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 24(12), 1990–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., de Vries, S., Spreeuwenberg, P., Schellevis, F. G., & Groenewegen, P. P. (2009). Morbidity is related to a green living environment. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 63(12), 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C., Roux, A. D., & Galea, S. (2008). Are neighbourhood characteristics associated with depressive symptoms? A review of evidence. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 62(11), 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAneney, H., Tully, M. A., Hunter, R. F., Kouvonen, A., Veal, P., Stevenson, M., & Kee, F. (2015). Individual factors and perceived community characteristics in relation to mental health and mental well-being. BMC Public Health, 15, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2023). Civil affairs statistics for the 2nd quarter of 2023. Available online: https://www.mca.gov.cn/mzsj/tjsj/2023/202302tjsj.html (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2024). 2023 National report on the development of aging undertakings. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202410/content_6979487.htm (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Moustakas, L. (2022). Sport for social cohesion: Transferring from the pitch to the community? Social Sciences, 11(11), 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y., Yi, M., & Liu, Q. (2023). Association of neighborhood recreational facilities and depressive symptoms among Chinese older adults. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2011). The 2010 population census of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/pcsj/rkpc/6rp/indexch.htm (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2024). 2024 China Statistical Yearbook. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2024/indexch.htm (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2025). China’s population over 60 exceeds 300 million for the first time in 2024. Available online: https://laoling.cctv.com/2025/01/17/ARTI1YQU2WRMlO75bKSmmyLY250117.shtml (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Newman, M. G., & Zainal, N. H. (2020). The value of maintaining social connections for mental health in older people. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e12–e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P. J., Aenchbacher, L. E., & Dishman, R. K. (1993). Physical activity and depression in the elderly. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity, 1(1), 34–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orstad, S. L., Szuhany, K., Tamura, K., Thorpe, L. E., & Jay, M. (2020). Park proximity and use for physical activity among urban residents: Associations with mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A., Bejarano, C. M., Cushing, C. C., Staggs, V. S., Papa, A. E., Steel, C., Shook, R. P., Sullivan, D. K., Couch, S. C., Conway, T. L., Saelens, B. E., Glanz, K., Frank, L. D., Cain, K. L., Kerr, J., Schipperijn, J., Sallis, J. F., & Carlson, J. A. (2020). Differences in adolescent activity and dietary behaviors across home, school, and other locations warrant location-specific intervention approaches. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 17, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H., & Kang, S.-W. (2023). Social interaction and life satisfaction among older adults by age group. Healthcare, 11(22), 2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, C., Regidor, E., Astasio, P., Ortega, P., Navarro, P., & Domínguez, V. (2007). The association of current and sustained area-based adverse socioeconomic environment with physical inactivity. Social Science & Medicine, 65(3), 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, M., Garcia, L., Abbas, A., Strain, T., Schuch, F. B., Golubic, R., Kelly, P., Khan, S., Utukuri, M., Laird, Y., Mok, A., Smith, A., Tainio, M., Brage, S., & Woodcock, J. (2022). Association between physical activity and risk of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(6), 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, D., Ehlenz, M. M., Andrade, R., Cloutier, S., & Larson, K. L. (2020). Do neighborhood walkability, transit, and parks relate to residents’ life satisfaction? Insights from Phoenix. Journal of the American Planning Association, 86(2), 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, F., Corriveau, H., Hébert, R., & Winter, D. A. (1997). Gait in the elderly. Gait & Posture, 5(2), 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautio, N., Filatova, S., Lehtiniemi, H., & Miettunen, J. (2018). Living environment and its relationship to depressive mood: A systematic review. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 64(1), 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarloos, D., Alfonso, H., Giles-Corti, B., Middleton, N., & Almeida, O. P. (2011). The built environment and depression in later life: The health in men study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(5), 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J. F., Owen, N., & Fisher, E. (2015). Ecological models of health behavior. In Health behavior: Theory, research, and practice (5th ed., pp. 43–64). Jossey-Bass/Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P. E., & Yager, T. J. (1989). Reliability and validity of screening scales: Effect of reducing scale length. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 42(1), 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A., & Misra, N. (2009). Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 18(1), 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokale, I. O., Conway, S. H., & Douphrate, D. I. (2022). Built environment and its association with depression among older adults: A systematic review. The Open Public Health Journal, 15(1), e187494452202030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soósová, M. S., Timková, V., Dimunová, L., & Mauer, B. (2021). Spirituality as a mediator between depressive symptoms and subjective well-being in older adults. Clinical Nursing Research, 30(5), 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress. (2018). Law of the People’s Republic of China on the protection of the rights and interests of the elderly. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-10/29/content_5647622.htm (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Steenhuis, I. H., Nooy, S. B., Moes, M. J., & Schuit, A. J. (2009). Financial barriers and pricing strategies related to participation in sports activities: The perceptions of people of low income. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 6(6), 716–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturm, R., & Cohen, D. (2014). Proximity to urban parks and mental health. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 17(1), 19. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, H., Weaver, N., Patterson, J., Jones, P., Bell, T., Playle, R., Dunstan, F., Palmer, S., Lewis, G., & Araya, R. (2007). Mental health and quality of residential environment. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(6), 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Cai, Y., Xiong, X., & Xu, G. (2025). Evaluating accessibility and equity of multi-level urban public sports facilities at the residential neighborhood scale. Buildings, 15(10), 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weich, S., Blanchard, M., Prince, M., Burton, E., Erens, B. O. B., & Sproston, K. (2002). Mental health and the built environment: Cross–sectional survey of individual and contextual risk factors for depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180(5), 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Withall, J., Jago, R., & Fox, K. R. (2011). Why some do but most don’t. Barriers and enablers to engaging low-income groups in physical activity programmes: A mixed methods study. BMC Public Health, 11, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, L., Hooper, P., Foster, S., & Bull, F. (2017). Public green spaces and positive mental health–investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental wellbeing. Health & Place, 48, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (2005). Mental health: Facing the challenges, building solutions. In Report from the WHO European ministerial conference. WHO Regional Office for Europe. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2022). World mental health report: Transforming mental health for all. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua News Agency. (2018). Older people will make up about a third of our total population by 2050. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-07/19/content_5307839.htm (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Yen, I. H., Michael, Y. L., & Perdue, L. (2009). Neighborhood environment in studies of health of older adults: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(5), 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z., Feng, Z. M., & Yang, Y. Z. (2018). Relief degree of land surface dataset of China (1 km). Journal of Global Change Data & Discovery, 2(2), 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, R., Cheung, O., Leung, J., Tong, C., Lau, K., Cheung, J., & Woo, J. (2019). Is neighbourhood social cohesion associated with subjective well-being for older Chinese people? The neighbourhood social cohesion study. BMJ Open, 9(5), e023332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | |||||

| Mental health | Ranging from “0” to “18”. The lower the CES-D score, the better their mental health. | 6.312 | 3.055 | 0 | 18 |

| Explanatory variable | |||||

| Public sports facility availability in living communities | Ranging from “0” to “3”. The higher the score, the greater the availability of public sports facilities. | 0.904 | 0.946 | 0 | 3 |

| Mediating variable | |||||

| Physical activity | 1 = less than one time per week; 2 = one time per week on average; 3 = two times per week on average; 4 = three times per week on average; 5 = four or more times per week on average | 3.970 | 0.669 | 1 | 5 |

| Life satisfaction | 1 = very dissatisfied; 2 = somewhat dissatisfied; 3 = normal; 4 = somewhat satisfied; 5 = very satisfied | 3.861 | 0.781 | 1 | 5 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Age | Years old | 69.848 | 7.308 | 60 | 103 |

| Gender | 1 = male; 0 = female | 0.516 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| Education | 1 = illiterate; 2 = primary school; 3 = junior high school; 4 = high school; 5 = junior college and above | 2.224 | 0.720 | 1 | 5 |

| Marital status | 1 = married; 0 = otherwise | 0.734 | 0.442 | 0 | 1 |

| Hukou | 1 = rural; 0 = urban | 0.374 | 0.484 | 0 | 1 |

| Living arrangement | 1 = not living alone; 0 = living alone | 0.886 | 0.318 | 0 | 1 |

| Chronic diseases | 1 = diagnosed; 0 = otherwise | 0.585 | 0.493 | 0 | 1 |

| Income | Logarithm of annual income | 8.975 | 2.133 | 0 | 15.425 |

| Hospitalization frequency | Times (within the past two years) | 0.492 | 1.153 | 0 | 72 |

| Regional economic development | Logarithm of regional Gross Domestic Product in 2016 | 10.205 | 0.619 | 7.853 | 11.300 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| OLS | IV-2SLS | |

| Public sports facility availability in living communities | −0.225 *** | −2.283 *** |

| (0.037) | (0.304) | |

| Age | 0.023 *** | 0.029 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | |

| Gender | −0.026 | −0.052 |

| (0.070) | (0.081) | |

| Education | −0.290 *** | −0.070 |

| (0.050) | (0.066) | |

| Marital status | −0.347 *** | −0.398 *** |

| (0.093) | (0.107) | |

| Hukou | 0.356 *** | −0.695 *** |

| (0.077) | (0.173) | |

| Living arrangement | −0.732 *** | −0.705 *** |

| (0.117) | (0.137) | |

| Chronic diseases | 0.570 *** | 0.688 *** |

| (0.070) | (0.084) | |

| Income | −0.119 *** | 0.001 |

| (0.019) | (0.028) | |

| Hospitalization frequency | 0.089 *** | 0.053 |

| (0.032) | (0.036) | |

| Regional economic development | −0.226 *** | 0.191 ** |

| (0.055) | (0.094) | |

| Instrumental variable tests | ||

| Weak IV identification test | Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F statistic | 186.412 *** |

| Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic | 127.529 *** | |

| Under-identification test | Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic | 145.171 *** |

| First-stage regression | F value | 186.410 *** |

| R2 | 0.074 | — |

| n | 7811 | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| Winsorization | Truncation | |

| Public sports facility availability in living communities | −2.283 *** | −2.482 *** |

| (0.304) | (0.342) | |

| Age | 0.030 *** | 0.025 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.007) | |

| Gender | −0.052 | −0.058 |

| (0.081) | (0.086) | |

| Education | −0.070 | −0.060 |

| (0.066) | (0.071) | |

| Marital status | −0.407 *** | −0.382 *** |

| (0.107) | (0.114) | |

| Hukou | −0.698 *** | −0.781 *** |

| (0.173) | (0.188) | |

| Living arrangement | −0.699 *** | −0.737 *** |

| (0.137) | (0.148) | |

| Chronic diseases | 0.687 *** | 0.701 *** |

| (0.084) | (0.088) | |

| Income | 0.001 | 0.024 |

| (0.028) | (0.031) | |

| Hospitalization frequency | 0.052 | 0.030 |

| (0.036) | (0.037) | |

| Regional economic development | 0.193 ** | 0.245 ** |

| (0.094) | (0.101) | |

| n | 7811 | 7427 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Married | Otherwise | Diagnosed Chronic Diseases | Otherwise | |

| Public sports facility availability in living communities | −2.768 *** | −1.835 *** | −2.956 *** | −1.058 ** | −1.159 *** | −5.659 *** |

| (0.466) | (0.401) | (0.432) | (0.416) | (0.307) | (1.058) | |

| Age | 0.025 *** | 0.031 *** | 0.028 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.024 *** | 0.018 |

| (0.009) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.009) | (0.007) | (0.015) | |

| Gender | −0.028 | −0.071 | 0.009 | −0.155 | ||

| (0.103) | (0.150) | (0.094) | (0.196) | |||

| Education | 0.038 | −0.184 ** | −0.030 | −0.149 | −0.144 * | 0.153 |

| (0.099) | (0.090) | (0.085) | (0.117) | (0.077) | (0.168) | |

| Marital status | −0.362 ** | −0.393 *** | −0.480 *** | −0.699 ** | ||

| (0.184) | (0.130) | (0.122) | (0.299) | |||

| Hukou | −0.987 *** | −0.439 * | −0.999 *** | −0.140 | −0.072 | −1.966 *** |

| (0.261) | (0.231) | (0.238) | (0.259) | (0.201) | (0.451) | |

| Living arrangement | −0.718 *** | −0.753 *** | −0.446 | −0.724 *** | −0.755 *** | −0.117 |

| (0.244) | (0.165) | (0.327) | (0.139) | (0.150) | (0.375) | |

| Chronic diseases | 0.770 *** | 0.607 *** | 0.708 *** | 0.781 *** | ||

| (0.122) | (0.116) | (0.110) | (0.146) | |||

| Income | 0.030 | −0.017 | 0.052 | −0.094 ** | −0.065 ** | 0.147 ** |

| (0.044) | (0.035) | (0.038) | (0.041) | (0.033) | (0.068) | |

| Hospitalization frequency | 0.066 | 0.045 | 0.037 | 0.071 | 0.062 * | 0.160 |

| (0.051) | (0.048) | (0.046) | (0.054) | (0.037) | (0.128) | |

| Regional economic development | 0.441 *** | −0.066 | 0.409 *** | −0.251 * | −0.102 | 0.981 *** |

| (0.140) | (0.126) | (0.128) | (0.136) | (0.102) | (0.273) | |

| n | 4030 | 3781 | 5734 | 2077 | 4566 | 3245 |

| Mediating Effect | Direct Effect | |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Physical activity | ||

| Normal-based [95% confidence interval] | [−0.009, −0.001] | [−0.293, −0.148] |

| p value | 0.029 | 0.000 |

| Bias-corrected [95% confidence interval] | [−0.010, −0.001] | [−0.292, −0.148] |

| Panel B: Life satisfaction | ||

| Normal-based [95% confidence interval] | [−0.074, −0.043] | [−0.238, −0.095] |

| p value | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Bias-corrected [95% confidence interval] | [−0.075, −0.044] | [−0.239, −0.096] |

| Control variables | Controlled | Controlled |

| n | 7811 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, S.; Jiang, S.; Dong, X.; Guo, X.; Chen, M. Public Sports Facility Availability in Living Communities and Mental Health of Older People in China: The Mediating Effect of Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070991

Yan S, Jiang S, Dong X, Guo X, Chen M. Public Sports Facility Availability in Living Communities and Mental Health of Older People in China: The Mediating Effect of Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):991. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070991

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Shuhan, Shengzhong Jiang, Xiaodong Dong, Xiuqi Guo, and Mingzhe Chen. 2025. "Public Sports Facility Availability in Living Communities and Mental Health of Older People in China: The Mediating Effect of Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070991

APA StyleYan, S., Jiang, S., Dong, X., Guo, X., & Chen, M. (2025). Public Sports Facility Availability in Living Communities and Mental Health of Older People in China: The Mediating Effect of Physical Activity and Life Satisfaction. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 991. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070991