How Will I Evaluate Others? The Influence of “Versailles Literature” Language Style on Social Media on Consumer Attitudes Towards Evaluating Green Consumption Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Language Style and Versailles Literature

2.2. Hypocrisy Perception

2.3. Bragging Perception

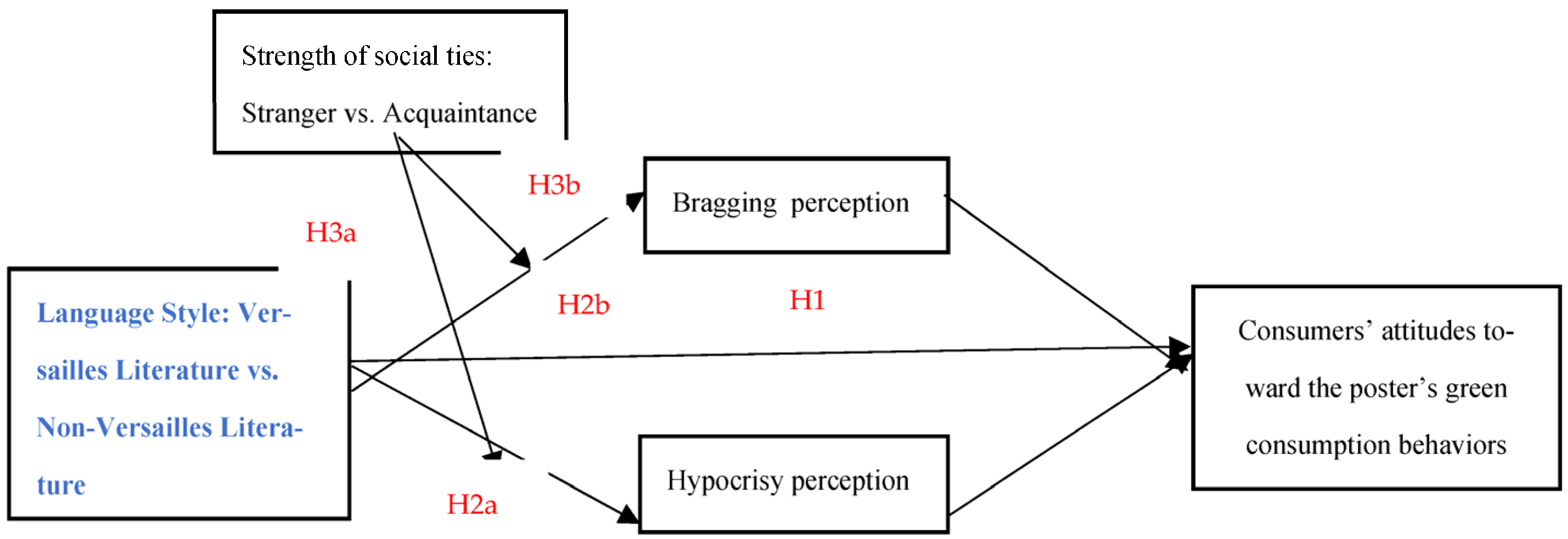

3. Research Hypotheses

4. Experimental Design and Testing

4.1. Overview of Studies

4.2. Experiment 1

4.2.1. Pilot Experiment

4.2.2. Formal Experiment

4.2.3. Experimental Results

4.3. Experiment 2

Experimental Results

4.4. Experiment 3

Experimental Results

5. Discussions

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Research Limitations and Future Research Directions

6. Research Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahamad, N. R., & Ariffin, M. (2018). Assessment of knowledge, attitude and practice towards sustainable consumption among university students in Selangor, Malaysia. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 16, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D., Grace, A., Palmer, J., & Pham, C. (2017). Investigating the direct and indirect effects of corporate hypocrisy and perceived corporate reputation on consumers’ attitudes toward the company. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D., Tan, L. P., Tjiptono, F., & Yang, L. (2018). Exploring consumers’ purchase intention towards green products in an emerging market: The role of consumers’ perceived readiness. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(4), 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F. (1982). A self-presentational view of social phenomena. Psychological Bulletin, 91(1), 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazarova, N. N., & Choi, Y. H. (2014). Self-disclosure in social media: Extending the functional approach to disclosure motivations and characteristics on social network sites. Journal of Communication, 64(4), 635–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W. O., & Etzel, M. J. (1982). Reference group influence on product and brand purchase decisions. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard, S. A. N., & Tolmie, C. R. (2018). Millennials’ green consumption behaviour: Exploring the role of social media. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(6), 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J., & Ward, M. (2010). Subtle signals of inconspicuous consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(4), 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergsieker, H. B., Shelton, J. N., & Richeson, J. A. (2010). To be liked versus respected: Divergent goals in interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(2), 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, J. Z., Levine, E. E., Barasch, A., & Small, D. A. (2015). The Braggart’s dilemma: On the social rewards and penalties of advertising prosocial behavior. Journal of Marketing Research, 52(1), 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. J., & Reingen, P. H. (1987). Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 14(3), 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C. T., & Yen, C. T. (2013). Missing ingredients in metaphor advertising: The right formula of metaphor type, product type, and need for cognition. Journal of Advertising, 42(1), 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Liu, S. Q., & Mattila, A. S. (2020). Bragging and humblebragging in online reviews. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S. C., & Kim, Y. (2011). Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. International Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science. Technometrics, 31(4), 499–500. [Google Scholar]

- Coupland, N. (2007). Style: Language variation and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critcher, C. R., Helzer, E. G., & Tannenbaum, D. (2020). Moral character evaluation: Testing another’s moral-cognitive machinery. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 87, 103906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čapienė, A., Rūtelionė, A., & Krukowski, K. (2022). Engaging in sustainable consumption: Exploring the influence of environmental attitudes, values, personal norms, and perceived responsibility. Sustainability, 14(16), 10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M. D., Huluba, G., & Beldad, A. D. (2020). Different shades of greenwashing: Consumers’ reactions to environmental lies, half-lies, and organizations taking credit for following legal obligations. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 34(1), 38–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A., Schlegelmilch, B. B., Sinkovics, R. R., & Bohlen, G. M. (2003). Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. Journal of Business Research, 56(6), 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, K. (2019). Humble-bragging as a self presentation strategy: Role of gender of bragger and type of brag. Proceedings for Mediated Minds, 2(2). [Google Scholar]

- Ellen, P. S., Wiener, J. L., & Cobb-Walgren, C. (1991). The role of perceived consumer effectiveness in motivating environmentally conscious behaviors. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 10(2), 102–117. [Google Scholar]

- Fassin, Y., & Buelens, M. (2011). The hypocrisy-sincerity continuum in corporate communication and decision making: A model of corporate social responsibility and business ethics practices. Management Decision, 49(4), 586–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W., Chang, D., & Sun, H. (2023). The impact of social media influencers’ bragging language styles on consumers’ attitudes toward luxury brands: The dual mediation of envy and trustworthiness. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1113655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafter, L. M., & Tchetchik, A. (2017). The role of social ties and communication technologies in visiting friends tourism-A GMM simultaneous equations approach. Tourism Management, 61, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1949). Presentation of self in everyday life. American Journal of Sociology, 55(1), 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg, J., Libai, B., & Muller, E. (2001). Talk of the network: A complex systems look at the underlying process of word-of-mouth. Marketing Letters, 12, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, S. M., Hodge, F. D., & Sinha, R. K. (2018). How disclosure medium affects investor reactions to CEO bragging, modesty, and humblebragging. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 68, 118–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J. M., & Van den Bergh, B. (2010). Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(3), 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, R., Blakey, W., & Gray, K. (2022). Deconstructing moral character judgments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 43, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbaugh, E. E. (2021). Self-presentation in social media: Review and research opportunities. Review of Communication Research, 9, 80–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.-j. (2022). Analysis of “Versailles Literature” from the perspective of speech act theory. Journal of Literature and Art Studies, 12(4), 373–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I., Kassinis, G., & Papagiannakis, G. (2023). The impact of perceived greenwashing on customer satisfaction and the contingent role of capability reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 185(2), 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L., & Liu, X. (2021). “Versailles Literature”: A discourse confrontation between construction and deconstruction. Exploration and Contention, 7, 162–169+180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E. E., & Nisbett, R. E. (1987). The actor and the observer: Divergent perceptions of the causes of behavior. In Preparation of this paper grew out of a workshop on attribution theory held at University of California, Los Angeles, August 1969. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. Psychological Perspectives on the Self, 1(1), 231–262. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, A. H., & Monin, B. (2008). From sucker to saint: Moralization in response to self-threat. Psychological Science, 19(8), 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khafifah, S., Aibonotika, A., & Widiati, S. W. (2024). Language style in pocky brand snack product advertisements in Japanese. Journal of Education Technology Information Social Sciences and Health, 3(1), 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. M. (2022). Social comparison of fitness social media postings by fitness app users. Computers in Human Behavior, 131, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Lee, J. E. R. (2011). The Facebook paths to happiness: Effects of the number of Facebook friends and self-presentation on subjective well-being. CyberPsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(6), 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konuk, F. A., & Otterbring, T. (2024). The dark side of going green: Dark triad traits predict organic consumption through virtue signaling, status signaling, and praise from others. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 76, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J., Hagemeyer, B., Lösch, T., & Rentzsch, K. (2020). Accuracy and bias in the social perception of envy. Emotion, 20(8), 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, K., Weng, Q., Pitafi, A. H., Ali, A., Siddiqui, A. W., Malik, M. Y., & Latif, Z. (2021). Social comparison as a double-edged sword on social media: The role of envy type and online social identity. Telematics and Informatics, 56, 101470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leary, M. R., & Kowalski, R. M. (1990). Impression management: A literature review and two-component model. Psychological Bulletin, 107(1), 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leban, M., Thomsen, T. U., Von Wallpach, S., & Voyer, B. G. (2021). Constructing personas: How high-net-worth social media influencers reconcile ethicality and living a luxury lifestyle. Journal of Business Ethics, 169(2), 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. A., & Eastin, M. S. (2020). I like what she’s# endorsing: The impact of female social media influencers’ perceived sincerity, consumer envy, and product type. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 20(1), 76–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. A., & Xu, X. (2017). Effectiveness of online consumer reviews: The influence of valence, reviewer ethnicity, social distance and source trustworthiness. Internet Research, 27(2), 362–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. (2022, December 16). A socio-pragmatic analysis of “Versailles Literature” from the perspective of dramaturgical theory and memetics. In 2022 2nd international conference on modern educational technology and social sciences (ICMETSS 2022) (pp. 624–633). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M., & Hancock, J. T. (2020). Modified self-praise in social media: Humblebragging, self-presentation, and perceptions of (in) sincerity. In Complimenting behavior and (self-) praise across social media (pp. 289–310). John Benjamins Publishing Company. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q., & Zhong, D. (2015). Using social network analysis to explain communication characteristics of travel-related electronic word-of-mouth on social networking sites. Tourism Management, 46, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z., Huang, X., Chen, S., Wei, H., & Yang, D. (2017). The relationship between corporate social responsibility types and brand hypocrisy. Advances in Psychological Science, 25(10), 1642–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C., Jiang, Y., Miao, M., & Zhang, H. (2023). Will humblebragging advertising necessarily trigger consumers’ negative brand attitudes-based on the perspective of the motives of self-presentation. Journal of Marketing Science, 2(4), 137–156. [Google Scholar]

- Marder, B., Archer-Brown, C., Colliander, J., & Lambert, A. (2019). Vacation posts on Facebook: A model for incidental vicarious travel consumption. Journal of Travel Research, 58(6), 1014–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massara, F., Scarpi, D., & Porcheddu, D. (2020). Can your advertisement go abstract without affecting willingness to pay? Product-centered versus lifestyle content in luxury brand print advertisements. Journal of Advertising Research, 60(1), 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, E., Tjomsland, H. E., & Huegel, D. (2016). The distance between us: Using construal level theory to understand interpersonal distance in a digital age. Frontiers in Digital Humanities, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, G., Gershoff, A. D., & Wooten, D. B. (2016). When boastful word of mouth helps versus hurts social perceptions and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(1), 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulos, A., Poulis, A., Theodoridis, P., & Kalampakas, A. (2022). Influencing green purchase intention through eco labels and user-generated content. Sustainability, 15(1), 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramita, W., & Septianto, F. (2021). The benefits and pitfalls of humblebragging in social media advertising: The moderating role of the celebrity versus influencer. International Journal of Advertising, 40(8), 1294–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M., & Abell, A. (2021). More trust in fewer followers: Diverging effects of popularity metrics and green orientation social media influencers. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 56(1), 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W., & Guo, Y. (2021). What is “Versailles Literature”?: Humblebrags on Chinese social networking sites. Journal of Pragmatics, 184, 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renton, M., & Simmonds, H. (2017). Like is a verb: Exploring tie strength and casual brand use effects on brand attitudes and consumer online goal achievement. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 26(4), 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rim, S., Uleman, J. S., & Trope, Y. (2009). Spontaneous trait inference and construal level theory: Psychological distance increases nonconscious trait thinking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(5), 1088–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Roy Chaudhuri, H., Mazumdar, S., & Ghoshal, A. (2011). Conspicuous consumption orientation: Conceptualisation, scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 10(4), 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmuck, D., Matthes, J., & Naderer, B. (2018). Misleading consumers with green advertising? An affect–reason–involvement account of greenwashing effects in environmental advertising. Journal of Advertising, 47(2), 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scopelliti, I., Loewenstein, G., & Vosgerau, J. (2015). You call it “Self-Exuberance”; I call it “Bragging” miscalibrated predictions of emotional responses to self-promotion. Psychological Science, 26(6), 903–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedikides, C., & Gregg, A. P. (2008). Self-enhancement: Food for thought. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezer, O., Gino, F., & Norton, M. I. (2018). Humblebragging: A distinct—And ineffective—Self-presentation strategy. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(1), 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, D., & Wu, W. (2022). Does green morality lead to collaborative consumption behavior toward online collaborative redistribution platforms? Evidence from emerging markets shows the asymmetric roles of pro-environmental self-identity and green personal norms. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 68, 102993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., & Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organizational Identity: A Reader, 56(65), 9780203505984-16. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, K., & Robles, J. S. (2013). Everyday talk: Building and reflecting identities. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2010). Construal-level theory of psychological distance. Psychological Review, 117(2), 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Ven, N. (2016). Envy and its consequences: Why it is useful to distinguish between benign and malicious envy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(6), 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T., Lutz, R. J., & Weitz, B. A. (2009). Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Yang, X., Xi, Y., & He, Z. (2022). Is green spread? The spillover effect of community green interaction on related green purchase behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z., & Zhu, H. (2020). Consumer response to perceived hypocrisy in corporate social responsibility activities. Sage Open, 10(2), 2158244020922876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittels, H. (2012). Humblebrag: The art of false modesty. Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, C., Bagozzi, R. P., & Grønhaug, K. (2015). The role of moral emotions and individual differences in consumer responses to corporate green and non-green actions. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D., Sengupta, J., & Hong, J. (2016). Why does psychological distance influence construal level? The role of processing mode. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(4), 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H., Wei, Y., Shen, C., & Xiong, H. (2024). Bragging or humblebragging? The impact of travel bragging on viewer behavior. Tourism Review, 80(5), 1067–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Liang, X., & Qi, C. (2021). Investigating the impact of interpersonal closeness and social status on electronic word-of-mouth effectiveness. Journal of Business Research, 130, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Yao, J., & Huang, M. (2013). Dual motives of harmony and negotiation outcomes in an integrative negotiation. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 45(9), 1026–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., Shan, M., & Fang, X. (2023). “Literal” or “Figurative”: The effect of online review language style on consumer purchase intention. Collected Essays on Finance and Economics, 39(11), 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, B. (2023). ‘Versailles literature’ on WeChat Moments–humblebragging with digital technologies. Discourse & Communication, 17(5), 662–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic Dimension | Versailles Literature | Direct Bragging | Virtue Signaling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apply perspective | third-person perspective | first-person perspective | collective identity expression |

| Comparison strategy | reverse contrast, desire to rise first and restrain first | positive comparison or independent statement | contrast with unethical behavior |

| Language characteristics | ostensibly humble, ostensibly ostentatious | explicit self-praise | values manifesto |

| Social influence | arouse audience disgust and reduce social support | enhance impression and trigger jealousy | enhance group identity and may trigger moral licensing effect |

| Related literature | Scopelliti et al. (2015); Sezer et al. (2018) | Sedikides and Gregg (2008); Grant et al. (2018) | Jordan and Monin (2008); Konuk and Otterbring (2024) |

| Experiment | Purpose | Method | Sample Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | Main effect, Mediating effect | To verify the direct impact of “Versailles Literature” language style on green consumption behavior and its mediating mechanism | Used a one-way intergroup design (language Style: Versailles Literature vs. non-Versailles Literature) | N = 60 35% male |

| Experiment 2 | Moderating effect | Verify the moderating effect of the strength of social ties | Used a two-factor design of 2 (language style: Versailles Literature vs non-Versailles Literature) × 2 (strength of social ties: stranger vs. acquaintance) | N = 120 28.3% male |

| Experiment 3 | Moderating effect | Platform differentiation design is used to control the strength of social ties and enhance the moderating effect of the strength of social ties | Used a two-factor design of 2 (language style: Versailles Literature vs. non-Versailles Literature) × 2 (strength of social ties: stranger vs. acquaintance) | N = 124 25.8% male |

| Parameter | Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 21 | 35 |

| Female | 39 | 65 | |

| Age | Under 18 | 13 | 21.7 |

| 19–25 | 44 | 73.3 | |

| 26–30 | 3 | 5 | |

| Education | Undergraduate | 57 | 95 |

| Postgraduate and above | 3 | 5 | |

| Occupation | Student | 60 | 100 |

| Variables | Laten Variables | S.E. | C.R. | p | Std. Factor Loading | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | BP1 | 0.867 | 0.860 | 0.948 | 0.949 | |||

| BP2 | 0.101 | 11.806 | *** | 0.968 | ||||

| BP3 | 0.108 | 11.177 | *** | 0.945 | ||||

| HP | HP1 | 0.901 | 0.897 | 0.963 | 0.963 | |||

| HP2 | 0.079 | 13.265 | *** | 0.956 | ||||

| HP3 | 0.079 | 14.527 | *** | 0.983 | ||||

| LS | LS1 | 0.889 | 0.851 | 0.944 | 0.945 | |||

| LS2 | 0.089 | 12.349 | *** | 0.969 | ||||

| LS3 | 0.094 | 10.744 | *** | 0.907 |

| Variables | Variables | M | SD | p | S2pooled | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| attitudes toward the poster’s green consumption behavior | non-Versailles Literature | 12.43 | 2.239 | 0.000 | 6.497 | 1.399 |

| Versailles Literature | 8.867 | 2.825 | ||||

| bragging perception | non-Versailles Literature | 6.2 | 2.964 | 0.000 | 7.441 | 2.053 |

| Versailles Literature | 11.8 | 2.469 | ||||

| hypocrisy perception | non-Versailles Literature | 5.167 | 2.854 | 0.000 | 7.029 | 2.389 |

| Versailles Literature | 11.5 | 2.432 |

| Dependent Variable | Variables | β | t | p | VIF | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bragging perception | Constant | 1.995 | 0.051 | 0.532 | ||

| Language style | 0.710 | 6.739 | 0.000 | 1.303 | ||

| hypocrisy perception | Constant | 2.521 | 0.015 | 0.606 | ||

| Language style | 0.783 | 8.100 | 0.000 | 1.303 | ||

| attitudes toward the poster’s green consumption behavior | Constant | 3.423 | 0.001 | 0.429 | ||

| Bragging Perception | −0.582 | −5.282 | 0.000 | 1.170 | ||

| Constant | 3.560 | 0.001 | 0.424 | |||

| Hypocrisy Perception | −0.573 | −5.207 | 0.000 | 1.157 |

| Parameter | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 34 | 28.3 |

| Female | 86 | 71.7 | |

| Age | Under 18 | 15 | 12.5 |

| 19–25 | 103 | 85.8 | |

| 26–30 | 2 | 1.7 | |

| Education | Undergraduate | 120 | 100 |

| Occupation | Student | 120 | 100 |

| Variables | Laten Variables | S.E. | C.R. | p | Std. Factor Loading | AVE | CR | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP | BP1 | 0.809 | 0.800 | 0.923 | 0.921 | |||

| BP2 | 0.1 | 12.727 | *** | 0.929 | ||||

| BP3 | 0.107 | 12.954 | *** | 0.939 | ||||

| HP | HP1 | 0.959 | 0.866 | 0.951 | 0.950 | |||

| HP2 | 0.052 | 18.287 | *** | 0.895 | ||||

| HP3 | 0.047 | 21.995 | *** | 0.937 | ||||

| LS | LS1 | 0.917 | 0.876 | 0.955 | 0.954 | |||

| LS2 | 0.062 | 18.232 | *** | 0.934 | ||||

| LS3 | 0.056 | 19.627 | *** | 0.956 |

| Variables | Variables | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| attitudes toward the poster’s green consumption behavior | non-Versailles Literature Acquaintance group | 12.30 | 1.84 | −0.570 | 0.571 |

| non-Versailles Literature stranger group | 12.53 | 1.28 | |||

| Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 9.267 | 3.07 | 4.464 | 0.000 | |

| Versailles Literature stranger group | 6.20 | 2.17 | |||

| bragging perception | non-Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 5.20 | 1.95 | −2.251 | 0.028 |

| non-Versailles Literature stranger group | 6.37 | 2.06 | |||

| Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 8.60 | 3.35 | −4.906 | 0.000 | |

| Versailles Literature stranger group | 12.03 | 1.87 | |||

| hypocrisy perception | non-Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 5.13 | 1.83 | −1.200 | 0.235 |

| non-Versailles Literature stranger group | 5.733 | 2.03 | |||

| Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 8.80 | 3.43 | −4.744 | 0.000 | |

| Versailles Literature stranger group | 12.27 | 2.07 |

| Dependent Variable: Attitudes Toward the Poster’s Green Consumption Behavior | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language Style | (I) Strength of Social Ties | (J) Strength of Social Ties | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. b | 95% Confidence Interval for Difference b | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| non-Versailles Literature | acquaintance | stranger | −0.233 | 0.565 | 0.681 | −1.353 | 0.887 |

| stranger | acquaintance | 0.233 | 0.565 | 0.681 | −0.887 | 1.353 | |

| Versailles Literature | acquaintance | stranger | 3.067 * | 0.565 | 0.000 | 1.947 | 4.187 |

| stranger | acquaintance | −3.067 * | 0.565 | 0.000 | −4.187 | −1.947 | |

| Parameter | Category | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 32 | 25.8 |

| Female | 92 | 74.2 | |

| Age | Under 18 | 1 | 0.8 |

| 19–25 | 121 | 97.6 | |

| 26–30 | 2 | 1.6 | |

| Education | Undergraduate | 110 | 88.7 |

| Postgraduate and above | 14 | 11.3 | |

| Monthly Income | under CNY 1000 | 63 | 50.8 |

| CNY 1000–2000 | 51 | 41.1 | |

| CNY 2000–3000 | 8 | 6.5 | |

| CNY 6000–10,000 | 2 | 1.6 |

| Variables | Variables | M | SD | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| attitudes toward the poster’s green consumption behavior | non-Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 12.16 | 1.92 | −0.360 | 0.720 |

| non-Versailles Literature stranger group | 12.35 | 2.30 | |||

| Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 9.81 | 2.95 | 5.518 | 0.000 | |

| Versailles Literature stranger group | 6.42 | 1.73 | |||

| bragging perception | non-Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 4.52 | 1.75 | −0.870 | 0.388 |

| non-Versailles Literature stranger group | 5.03 | 2.56 | |||

| Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 9.19 | 2.61 | −3.422 | 0.001 | |

| Versailles Literature stranger group | 11.55 | 2.80 | |||

| hypocrisy perception | non-Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 4.61 | 1.71 | −0.728 | 0.470 |

| non-Versailles Literature stranger group | 5.03 | 2.71 | |||

| Versailles Literature acquaintance group | 8.42 | 2.98 | −5.232 | 0.000 | |

| Versailles Literature stranger group | 12.00 | 2.38 |

| Dependent Variable | Variable | β | t | p | VIF | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bragging perception | Constant | −0.563 | 0.575 | 0.568 | ||

| language style | 0.703 | 11.430 | 0.000 | 0.703 | ||

| hypocrisy perception | Constant | 0.440 | 0.660 | 0.536 | ||

| language style | 0.653 | 10.235 | 0.000 | 0.653 | ||

| attitudes toward the poster’s green consumption behavior | Constant | 6.775 | 0.000 | 0.627 | ||

| bragging perception | −0.740 | −12.533 | 0.000 | −0.740 | ||

| Constant | 8.620 | 0.00 | 0.707 | |||

| hypocrisy perception | −0.813 | −15.250 | 0.000 | −0.813 |

| Dependent Variable: Attitudes Toward the Poster’s Green Consumption Behavior | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language Style | (I) Strength of Social Ties | (J) Strength of Social Ties | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. b | 95% Confidence Interval for Difference | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | ||||||

| non- Versailles Literature | acquaintance | stranger | −0.194 | 0.577 | 0.738 | −1.336 | 0.949 |

| stranger | acquaintance | 0.194 | 0.577 | 0.738 | −0.949 | 1.336 | |

| Versailles Literature | acquaintance | stranger | 3.387 * | 0.577 | 0.000 | 2.244 | 4.530 |

| stranger | acquaintance | −3.387 * | 0.577 | 0.000 | −4.530 | −2.244 | |

| Mediation Variables | Moderating Variables | Effect | SE | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bragging perception | acquaintance | 4.345 | 0.647 | 0.000 | 3.063 | 5.628 |

| stranger | 6.490 | 10.228 | 0.000 | 5.233 | 7.746 | |

| hypocrisy perception | acquaintance | 3.448 | 0.646 | 0.000 | 2.169 | 4.727 |

| stranger | 6.822 | 0.633 | 0.000 | 5.568 | 8.075 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; He, H. How Will I Evaluate Others? The Influence of “Versailles Literature” Language Style on Social Media on Consumer Attitudes Towards Evaluating Green Consumption Behavior. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070968

Zhang H, Liu H, Zhang Y, He H. How Will I Evaluate Others? The Influence of “Versailles Literature” Language Style on Social Media on Consumer Attitudes Towards Evaluating Green Consumption Behavior. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070968

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Huilong, Huiming Liu, Yudong Zhang, and Hui He. 2025. "How Will I Evaluate Others? The Influence of “Versailles Literature” Language Style on Social Media on Consumer Attitudes Towards Evaluating Green Consumption Behavior" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070968

APA StyleZhang, H., Liu, H., Zhang, Y., & He, H. (2025). How Will I Evaluate Others? The Influence of “Versailles Literature” Language Style on Social Media on Consumer Attitudes Towards Evaluating Green Consumption Behavior. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 968. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070968