Affect, Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors, and Orthorexia Nervosa Among Women: Mediation Through Intuitive Eating

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Affect, DEABs, and ON Behaviors

1.2. Intuitive Eating as a Mediator of the Relations Between Affect and DEABs or ON

1.3. The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. DEABs

2.2.2. Intuitive Eating

2.2.3. ON Behaviors

2.2.4. Positive and Negative Affect

2.3. Analyses

2.3.1. Preliminary Analyses

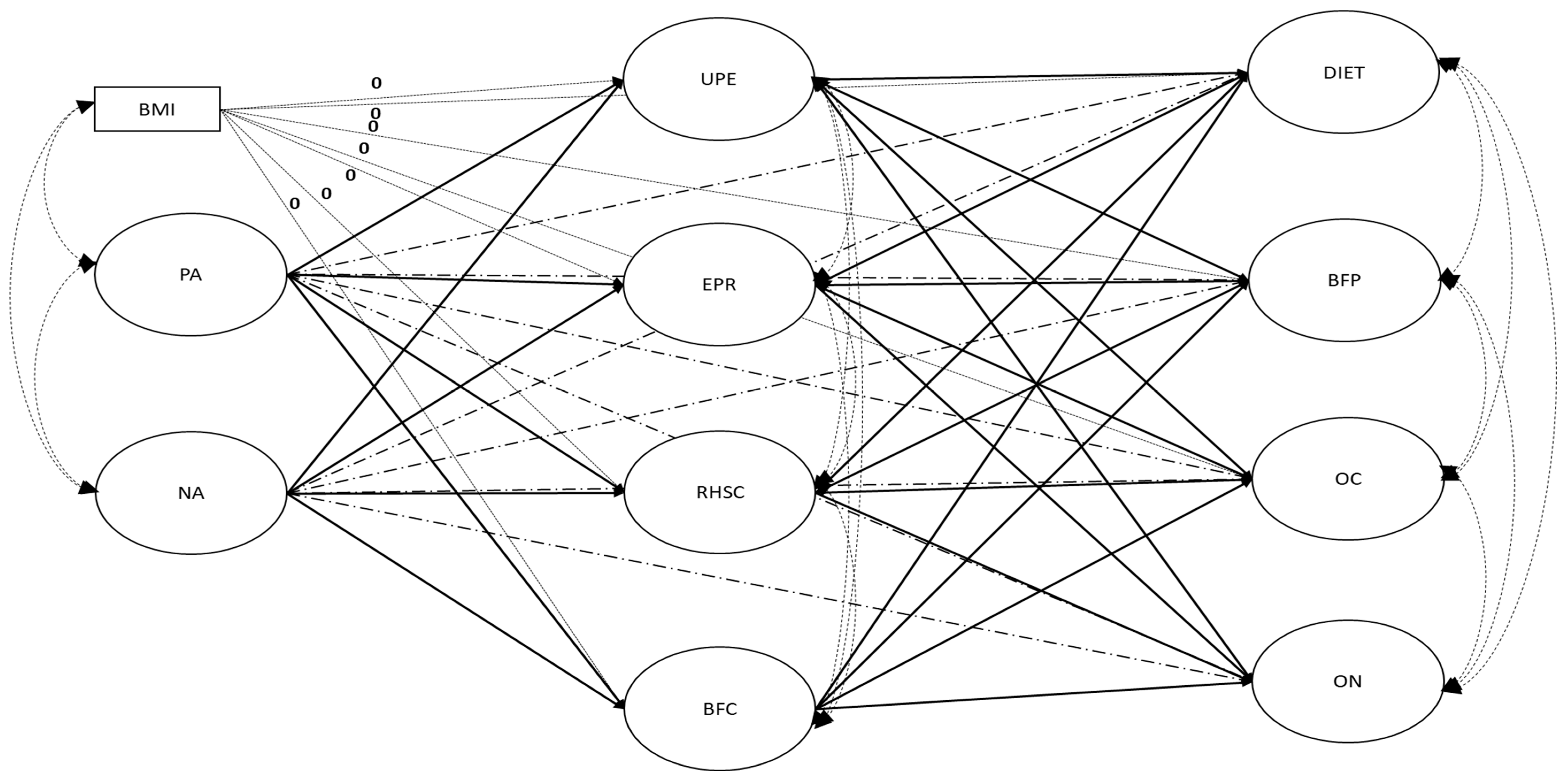

2.3.2. FM and PM Models

3. Results

3.1. Factor Validity and Reliability of the Latent Variables

3.2. Variable Correlations

3.3. Comparison of the Fully and Partially Mediated Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Relations Between Affect and DEABs or ON Behaviors

4.2. The Mediating Role of Intuitive Eating in the Relations Between Affect and DEABs or ON Behaviors

4.3. Limitations of the Present Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | A power estimation based on an online calculator developed by Preacher and Coffman (2006) was conducted using α = 0.05, a null RMSEA of 0.08, the sample size, and the model’s df and RMSEA value. The results revealed a power of 100% and indicated that a sample of 20 participants would be necessary to reach a power of 80%. |

| 2 | The results revealed a power of 100% and indicated that a sample of 20 participants would be necessary to reach a power of 80%. |

| 3 | See Note 2. |

References

- Aksoydan, E., & Camci, N. (2009). Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa among Turkish performance artists. Eating and Weight Disorders, 14, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Banna, M. H., Brazendale, K., Khan, M. S. I., Sayeed, A., Hasan, M. T., & Kundu, S. (2021). Association of overweight and obesity with the risk of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors among Bangladeshi university students. Eating Behaviors, 40, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiades, E., & Argyrides, M. (2022). Healthy orthorexia vs. orthorexia nervosa: Associations with body appreciation, functionality appreciation, intuitive eating and embodiment. Eating and Weight Disorders, 27(8), 3197–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anastasiades, E., & Argyrides, M. (2023). Exploring the role of positive body image in healthy orthorexia and orthorexia nervosa: A gender comparison. Appetite, 185, 106523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-Martinez, P., Perea-Moreno, A. J., Martinez-Jimenez, M. P., Redel-Macías, M. D., Pagliari, C., & Vaquero-Abellan, M. (2019). Social media, thin-ideal, body dissatisfaction and disordered eating attitudes: An exploratory analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16, 4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arslan, M., Yabanci Ayhan, N., Çevik, E., Sariyer, E., & Çolak, H. (2022). Effect of emotion regulation difficulty on eating attitudes and body mass index in university students: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Mens Health, 18(10), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarkaya, B., & Arcan, K. (2021). Teruel Ortoreksiya Ölçeği’nin (TOÖ) uyarlama, geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. Klinik Psikoloji Dergisi, 5(2), 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2010). Weighted least square estimation with missing data. Mplus Technical Appendix. Available online: www.statmodel.com/download/GstrucMissingRevision.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Atalay, S., Baş, M., Eren, B., & Karaca, E. (2020). Intuitive eating, diet quality, body mass index and abnormal eating: A cross-sectional study in young Turkish women. Progress in Nutrition, 22, e2020027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, E., Salameh, P., Sacre, H., Malaeb, D., Hallit, S., & Obeid, S. (2021). Association between impulsivity and orthorexia nervosa/healthy orthorexia: Any mediating effect of depression, anxiety, and stress? BMC Psychiatry, 21, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aytas, O., & Yaprak, B. (2023). Examination of eating disorder risk and effective factors in university students. Medicine Science, 12(3), 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrada, J. R., & Roncero, M. (2018). Bidimensional structure of the orthorexia: Development and initial validation of a new instrument. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 34, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthels, F., Barrada, J. R., & Roncero, M. (2019). Orthorexia nervosa and healthy orthorexia as new eating styles. PLoS ONE, 14, e0219609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosi, A. T. B., Camur, D., & Güler, C. (2007). Prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in resident medical doctors in the faculty of medicine (Ankara, Turkey). Appetite, 49, 661–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, S. J. (2003). Affect regulation and the development of psychopathology. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bratman, S., & Knight, D. (2004). Health food junkies: Orthorexia nervosa: Overcoming the obsession with healthful eating. Harmony. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C. S., Kola-Palmer, S., & Dhingra, K. (2015). Gender differences and correlates of extreme dieting behaviours in US adolescents. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(5), 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownell, K. D. (1991). Dieting and the search for the perfect body: Where physiology and culture collide. Behavior Therapy, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brytek-Matera, A. (2021). Negative affect and maladaptive eating behavior as a regulation strategy in normal-weight individuals: A narrative review. Sustainability, 13, 13704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brytek-Matera, A., Sacre, H., Staniszewska, A., & Hallit, S. (2020). The prevalence of orthorexia nervosa in polish and lebanese adults and its relationship with sociodemographic variables and bmi ranges: A cross-cultural perspective. Nutrients, 12, 3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bundros, J., Clifford, D., Silliman, K., & Morris, M. N. (2016). Prevalence of Orthorexia nervosa among college students based on Bratman’s test and associated tendencies. Appetite, 101, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caferoglu, Z., & Toklu, H. (2022). Intuitive eating: Associations with body weight status and eating attitudes in dietetic majors. Eating and Weight Disorders, 27, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbonneau, E., Carbonneau, N., Lamarche, B., Provencher, V., Bégin, C., Bradette-Laplante, M., Laramée, C., & Lemieux, S. (2016). Validation of a French-Canadian adaptation of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2 for the adult population. Appetite, 105, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, A., Oliveira, S., & Ferreira, C. (2020). Negative and positive affect and disordered eating: The adaptive role of intuitive eating and body image flexibility. Clinical Psychologist, 24, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cena, H., Barthels, F., Cuzzolaro, M., Bratman, S., Brytek-Matera, A., Dunn, T., Varga, M., Missbach, B., & Donini, L. M. (2019). Definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa: A narrative review of the literature. Eating and Weight Disorders, 24, 209–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chace, S., & Kluck, A. S. (2022). Validation of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale and relationship to health anxiety in a US sample. Eating and weight disorders-studies on Anorexia. Bulimia and Obesity, 27(4), 1437–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J. H., Bethoux, F., & Plow, M. A. (2024). Subjective well-being, positive affect, life satisfaction, and happiness with multiple sclerosis: A scoping review of the literature. Rehabilitation Nursing Journal, 49, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Wang, Z., Guo, B., Arcelus, J., Zhang, H., Jia, X., Xu, Y., Qiu, J., Xiao, Z., & Yang, M. (2012). Negative affect mediates effects of psychological stress on disordered eating in young Chinese women. Appetite, 59, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, G. W., & Lau, R. S. (2008). Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods, 11, 296–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Pressman, S. D. (2006). Positive affect and health. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coimbra, M., & Ferreira, C. (2021). Making the leap from healthy to disordered eating: The role of intuitive and inflexible eating attitudes in orthorexic behaviours among women. Eating and Weight Disorders, 26, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, R. E., & Horacek, T. (2010). Effectiveness of the my body knows when intuitive-eating pilot program. American Journal of Health Behavior, 34, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J. L., O’Shea, A. E., Atkinson, M. J., & Wade, T. D. (2014). Examination of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale and its relation to disordered eating in a young female sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, C. B., Hardan-Khalil, K., & Gibbs, K. (2017). Orthorexia nervosa: A review of the literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(12), 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craske, M. G., Dunn, B. D., Meuret, A. E., Rizvi, S. J., & Taylor, C. T. (2024). Positive affect and reward processing in the treatment of depression, anxiety and trauma. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgül, S. A., & Rigó, A. (2023). Orthorexia nervosa as a disorder of less intuition and emotion dysregulation. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar, 15, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denny, K. N., Loth, K., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Intuitive eating in young adults. Who is doing it, and how is it related to disordered eating behaviors? Appetite, 60, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dockray, S., & Steptoe, A. (2010). Positive affect and psychobiological processes. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L. M., Barrada, J. R., Barthels, F., Dunn, T. M., Babeau, C., Brytek-Matera, A., Cena, H., Cerolini, S., Cho, H. H., Coimbra, M., Cuzzolaro, M., Ferreira, C., Galfano, V., Grammatikopoulou, M. G., Hallit, S., Håman, L., Hay, P., Jimbo, M., Lasson, C., … Lombardo, C. (2022). A consensus document on definition and diagnostic criteria for orthorexia nervosa. Eating and Weight Disorders, 27(8), 3695–3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donini, L. M., Marsili, D., Graziani, M. P., Imbriale, M., & Cannella, C. (2004). Orthorexia nervosa: A preliminary study with a proposal for diagnosis and an attempt to measure the dimension of the phenomenon. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies, 9, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunn, T. M., & Bratman, S. (2016). On orthorexia nervosa: A review of the literature and proposed diagnostic criteria. Eating Behaviors, 21, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emiroğlu, E., & Aktaç, Ş. (2023). Food-related impulsivity in the triangle of obesity, eating behaviors and diet. Black Sea Journal of Health Science, 6, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive behaviour therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, N. J. (2015). Emotions, affects and the production of social life. British Journal of Sociology, 66, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gast, J., Madanat, H., & Nielson, A. C. (2012). Are men more intuitive when it comes to eating and physical activity? American Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaudreau, P., Sanchez, X., & Blondin, J. P. (2006). Positive and negative affective states in a performance-related setting: Testing the factorial structure of the PANAS across two samples of French-Canadian participants. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 22, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerges, S., Azzi, V., Bianchi, D., Laghi, F., Pompili, S., Malaeb, D., Obeid, S., Soufia, M., & Hallit, S. (2023). Exploring the relationship between dysfunctional metacognitive processes and orthorexia nervosa: The moderating role of emotion regulation strategies. BMC Psychiatry, 23, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, A. B., Aspen, V. P., Sinton, M. M., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., & Wilfley, D. E. (2008). Disordered eating attitudes and behaviors in overweight youth. Obesity, 16, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gratz, K. L., & Roemer, L. (2004). Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 26, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haedt-Matt, A. A., & Keel, P. K. (2011). Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 660–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawks, S. R., Madanat, H., Smith, T., & De La Cruz, N. (2008). Classroom approach for managing dietary restraint, negative eating styles, and body image concerns among college women. Journal of American College Health, 56, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayatbini, N. (2024). Examining the role of cognitive flexibility and distress tolerance in relation to orthorexia nervosa symptoms [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Miami University]. [Google Scholar]

- Heron, K. E., Scott, S. B., Sliwinski, M. J., & Smyth, J. M. (2014). Eating behaviors and negative affect in college women’s everyday lives. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 853–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, A. J. (2002). Prevalence and demographics of dieting. In K. D. Brownell, & B. T. Walsh (Eds.), Eating disorders and obesity: A comprehensive handbook (pp. 80–83). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howell, M. (2018). The relationship of dispositional mindfulness, emotion regulation, and body appreciation to intuitive eating in female emerging adults [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Oklahoma State University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Model, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izydorczyk, B., & Sitnik-Warchulska, K. (2018). Sociocultural appearance standards and risk factors for eating disorders in adolescents and women of various ages. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L., & Del Gaiso, A. K. (2006). Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kok, B. E., Coffey, K. A., Cohn, M. A., Catalino, L. I., Vacharkulksemsuk, T., Algoe, S. B., Brantley, M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). How positive emotions build physical health: Perceived positive social connections account for the upward spiral between positive emotions and vagal tone. Psychological Science, 24, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koushiou, M. I. (2016). Eating disorder risk: The role of sensitivity to negative affect and body-image inflexibility [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, University of Cyprus]. [Google Scholar]

- Koven, N. S., & Abry, A. W. (2015). The clinical basis of orthorexia nervosa: Emerging perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 11, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, R. S., & Cheung, G. W. (2012). Estimating and comparing specific mediation effects in complex latent variable models. Organizational Research Methods, 15, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichner, P., Steiger, H., Puentes-Neuman, G., Perreault, M., & Gottheil, N. (1994). Validation d’une échelle d’attitudes alimentaires auprès d’une population québécoise francophone [Validation of an eating attitude scale in a French-speaking Quebec population]. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie, 39, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J. (2022). Reciprocal associations between intuitive eating and positive body image components: A multi-wave, cross-lagged study. Appetite, 178, 106184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J., & Mitchell, S. (2017). Rigid dietary control, flexible dietary control, and intuitive eating: Evidence for their differential relationship to disordered eating and body image concerns. Eating Behaviors, 26, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, J., Tylka, T. L., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2021). Intuitive eating and its psychological correlates: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maïano, C., Aimé, A., Almenara, C. A., Gagnon, C., & Barrada, J. R. (2022). Psychometric of the Teruel Orthorexia Scale (TOS) among a French-Canadian adult sample. Eating and Weight Disorders, 27, 3457–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Grayson, D. (2005). Goodness of fit in structural equation. In A. Maydeu-Olivares, & J. J. McArdle (Eds.), Contemporary psychometrics (pp. 275–340). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu, J. (2005). What is orthorexia? Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 105, 1510–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, R. P. (1970). Theoretical foundations of principal factor analysis, canonical factor analysis, and alpha factor analysis. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 23, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. (2024). Mplus user’s guide. Version 8.11. Muthén & Muthén.

- Obeid, S., Hallit, S., Akel, M., & Brytek-Matera, A. (2021). Orthorexia nervosa and its association with alexithymia, emotion dysregulation and disordered eating attitudes among Lebanese adults. Eating and Weight Disorders, 26, 2607–2616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, M. (2017). Religion, culture and diet. In J. D’Silva, & J. Webster (Eds.), The meat crisis (pp. 291–298). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Palop-Larrea, V. (2024). Anger and physical and psychological health: A narrative review. Revista de Estudios Sociales, 90, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M. (2001). Age differences in perceived positive affect, negative affect, and affect balance in middle and old age. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2, 375–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Coffman, D. L. (2006). Computing power and minimum sample size for RMSEA [Computer software]. Available online: http://quantpsy.org/ (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Rainey, S. (2016, May 24). How TV’s new queens of healthy eating are serving up hogwash: Collagen soup. Eggs that are ‘astrologically harvested’ and why the Hemsley sisters don’t have a shred of expertise between them. Daily Mail. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, M. A., & Gentzler, A. L. (2015). An upward spiral: Bidirectional associations between positive affect and positive aspects of close relationships across the life span. Developmental Review, 36, 58–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rand-Giovannetti, D., Rozzell, K. N., & Latner, J. (2022). The role of positive self-compassion, distress tolerance, and social problem-solving in the relationship between perfectionism and disordered eating among racially and ethnically diverse college students. Eating Behaviors, 44, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rangel, C., Dukeshire, S., & MacDonald, L. (2012). Diet and anxiety. An exploration into the orthorexic society. Appetite, 58, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodgers, R. F., White, M., & Berry, R. (2021). Orthorexia nervosa, intuitive eating, and eating competence in female and male college students. Eating and Weight Disorders, 26, 2625–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruscitti, C., Rufino, K., Goodwin, N., & Wagner, R. (2016). Difficulties in emotion regulation in patients with eating disorders. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanlier, N., Yassibas, E., Bilici, S., Sahin, G., & Celik, B. (2016). Does the rise in eating disorders lead to increasing risk of orthorexia nervosa? Correlations with gender, education, and body mass index. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 55, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, U., & Treasure, J. (2006). Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 343–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvey, L. A., & Carey, M. G. (2013). Australia’s dietary guidelines and the environmental impact of food “from paddock to plate”. Medical Journal of Australia, 198, 18–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shateri, L., Arani, A. M., Shamsipour, H., Mousavi, E., & Saleck, L. (2018). The relationship between emotion regulation and intuitive eating in young women. Middle East Journal of Family Medicine, 7, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shouse, S. H., & Nilsson, J. (2011). Self-silencing, emotional awareness, and eating behaviors in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. S., Moskowitz, J. T., Mustanski, B., & Newcomb, M. E. (2024). Positive affect is associated with well-being among sexual and gender minorities and couples. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoor, S. T., Bekker, M. H., Van Strien, T., & van Heck, G. L. (2007). Relations between negative affect, coping, and emotional eating. Appetite, 48, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stice, E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strahler, J., Wachten, H., Neuhofer, S., & Zimmermann, P. (2022). Psychological correlates of excessive healthy and orthorexic eating: Emotion regulation, attachment, and anxious-depressive-stress symptomatology. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 817047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swami, V., Maïano, C., Furnham, A., & Robinson, C. (2022). The Intuitive Eating Scale-2: Re-evaluating its factor structure using a bifactor exploratory structural equation modelling framework. Eating and Weight Disorders, 27, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorne, J., Hussain, M., & Mantzios, M. (2022). Exploring the relationship between orthorexia nervosa, mindful eating and guilt and shame. Health Psychology Report, 11(1), 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tribole, E., & Resch, E. (2020). Intuitive eating, fourth edition: A revolutionary anti-diet approach. St. Martin’s Essentials. [Google Scholar]

- Tylka, T. L., & Kroon Van Diest, A. M. (2013). The Intuitive Eating Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation with college women and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylka, T. L., & Kroon Van Diest, A. M. (2015). Protective factors. In L. Smolak, & M. P. Levine (Eds.), The wiley handbook of eating disorders (pp. 430–444). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, N., & Drinkwater, E. J. (2014). Relationships between intuitive eating and health indicators: Literature review. Public Health Nutrition, 17, 1757–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuillier, L., Robertson, S., & Greville-Harris, M. (2020). Orthorexic tendencies are linked with difficulties with emotion identification and regulation. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wansink, B., Cheney, M. M., & Chan, N. (2003). Exploring comfort food preferences across age and gender. Physiology & Behavior, 79, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wee, S. (2023). Daily stress and negative affect as predictors of orthorexia nervosa symptoms among college students: Testing direct and moderated associations using daily diary methodology [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Department of Psychology, Southern Methodist University]. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, K., & Gross, J. J. (2010). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A conceptual framework. In A. M. Kring, & D. M. Sloan (Eds.), Emotion regulation and psychopathology: A transdiagnostic approach to etiology and treatment (pp. 13–37). Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside, U., Chen, E., Neighbors, C., Hunter, D., Lo, T., & Larimer, M. (2007). Difficulties regulating emotions: Do binge eaters have fewer strategies to modulate and tolerate negative affect? Eating Behaviors, 8, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakın, E., Raynal, P., & Chabrol, H. (2021). Not all personal definitions of healthy eating are linked to orthorexic behaviors among French college women. A cluster analysis study. Appetite, 162, 105164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz, H. Ö., & Arpa Zemzemoglu, T. E. (2021). The relationship between body mass index and eating disorder risk and intuitive eating among young adults. International Journal of Nutrition Sciences, 6, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DIET | BFP | OC | ON | UPE | EPR | RHSC | BFC | PA | NA | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIET | - | ||||||||||

| BFP | 0.800 | - | |||||||||

| OC | 0.711 | 0.707 | - | ||||||||

| ON | 0.779 | 0.818 | 0.685 | - | |||||||

| UPE | −0.842 | −0.736 | −0.678 | −0.823 | - | ||||||

| EPR | −0.384 | −0.492 | −0.097 | −0.212 | 0.185 | - | |||||

| RHSC | −0.648 | −0.644 | −0.386 | −0.512 | 0.593 | 0.507 | - | ||||

| BFC | −0.008 | −0.083 | −0.090 | 0.162 | −0.222 | 0.315 | 0.251 | - | |||

| PA | 0.007 | −0.068 | 0.051 | −0.003 | 0.048 | 0.102 | 0.208 | 0.242 | - | ||

| NA | 0.603 | 0.550 | 0.462 | 0.514 | −0.442 | −0.427 | −0.467 | −0.130 | 0.143 | - | |

| BMI(obs) | 0.206 | 0.096 | −0.279 | 0.080 | −0.042 | −0.219 | −0.201 | −0.115 | −0.026 | 0.212 | - |

| Direct Relations | b | SE | p | β | Direct Relations | b | SE | p | β |

| PA → UPE | 0.085 | 0.076 | 0.264 | 0.073 | EPR → DIET | −1.027 | 0.684 | 0.133 | −0.275 |

| PA → EPR | 0.192 | 0.072 | 0.007 | 0.170 | EPR → BFP | −0.639 | 0.154 | 0.000 | −0.358 |

| PA → RHSC | 0.359 | 0.080 | <0.001 | 0.299 | EPR → OC | −0.064 | 0.164 | 0.697 | −0.037 |

| PA → BFC | 0.249 | 0.079 | 0.002 | 0.239 | EPR → ON | −0.287 | 0.184 | 0.120 | −0.145 |

| NA → UPE | −0.587 | 0.086 | <0.001 | −0.508 | RHSC → DIET | 1.481 | 1.250 | 0.236 | 0.420 |

| NA → EPR | −0.522 | 0.080 | <0.001 | −0.461 | RHSC → BFP | 0.375 | 0.265 | 0.158 | 0.222 |

| NA → RHSC | −0.607 | 0.077 | <0.001 | −0.507 | RHSC → OC | 1.154 | 0.559 | 0.039 | 0.699 |

| NA → BFC | −0.189 | 0.072 | 0.009 | −0.182 | RHSC → ON | 0.736 | 0.386 | 0.057 | 0.394 |

| UPE → DIET | −4.499 | 2.651 | 0.090 | −1.233 | BFC → DIET | −1.582 | 1.080 | 0.143 | −0.390 |

| UPE → BFP | −1.617 | 0.358 | 0.000 | −0.925 | BFC → BFP | −0.564 | 0.219 | 0.010 | −0.291 |

| UPE → OC | −2.300 | 0.764 | 0.003 | −1.345 | BFC → OC | −1.206 | 0.466 | 0.010 | −0.635 |

| UPE → ON | −2.260 | 0.574 | 0.000 | −1.168 | BFC → ON | −0.521 | 0.265 | 0.049 | −0.242 |

| Indirect Relations | b | BCB 95% CI | Indirect Relations | b | BCB 95% CI | ||||

| PA → EPR → BFP | −0.123 | −0.435; −0.036 | NA → UPE → BFP | 0.949 | 0.793; 1.412 | ||||

| PA → BFC → BFP | −0.140 | −0.396; −0.039 | NA → EPR → BFP | 0.333 | 0.183; 0.590 | ||||

| PA → RHSC → OC | 0.414 | 0.084; 1.336 | NA → BFC → BFP | 0.107 | 0.023; 0.438 | ||||

| PA → BFC → OC | −0.300 | −0.846; −0.134 | NA → UPE → OC | 1.350 | 0.776; 3.044 | ||||

| PA → BFC → ON | −0.130 | −0.378; −0.033 | NA → RHSC → OC | −0.701 | −2.055; −0.245 | ||||

| NA → BFC → OC | 0.228 | 0.089; 0.485 | |||||||

| NA → UPE → ON | 1.326 | 0.933; 2.475 | |||||||

| NA → BFC → ON | 0.099 | 0.005; 0.263 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khoshzad, M.; Maïano, C.; Morin, A.J.S.; Aimé, A. Affect, Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors, and Orthorexia Nervosa Among Women: Mediation Through Intuitive Eating. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070967

Khoshzad M, Maïano C, Morin AJS, Aimé A. Affect, Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors, and Orthorexia Nervosa Among Women: Mediation Through Intuitive Eating. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):967. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070967

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhoshzad, Mehri, Christophe Maïano, Alexandre J. S. Morin, and Annie Aimé. 2025. "Affect, Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors, and Orthorexia Nervosa Among Women: Mediation Through Intuitive Eating" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070967

APA StyleKhoshzad, M., Maïano, C., Morin, A. J. S., & Aimé, A. (2025). Affect, Disordered Eating Attitudes and Behaviors, and Orthorexia Nervosa Among Women: Mediation Through Intuitive Eating. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 967. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070967