Social Media Use and Personal Relative Deprivation Among Urban Residents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Social Media Use and PRD

1.2. Subjective Social Status as a Mediator

1.3. Belief in a Just World as a Moderator

1.4. Present Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Social Media Use

2.2.2. Personal Relative Deprivation

2.2.3. Subjective Social Status

2.2.4. Belief in a Just World

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analysis

3.2. Mediation Analysis

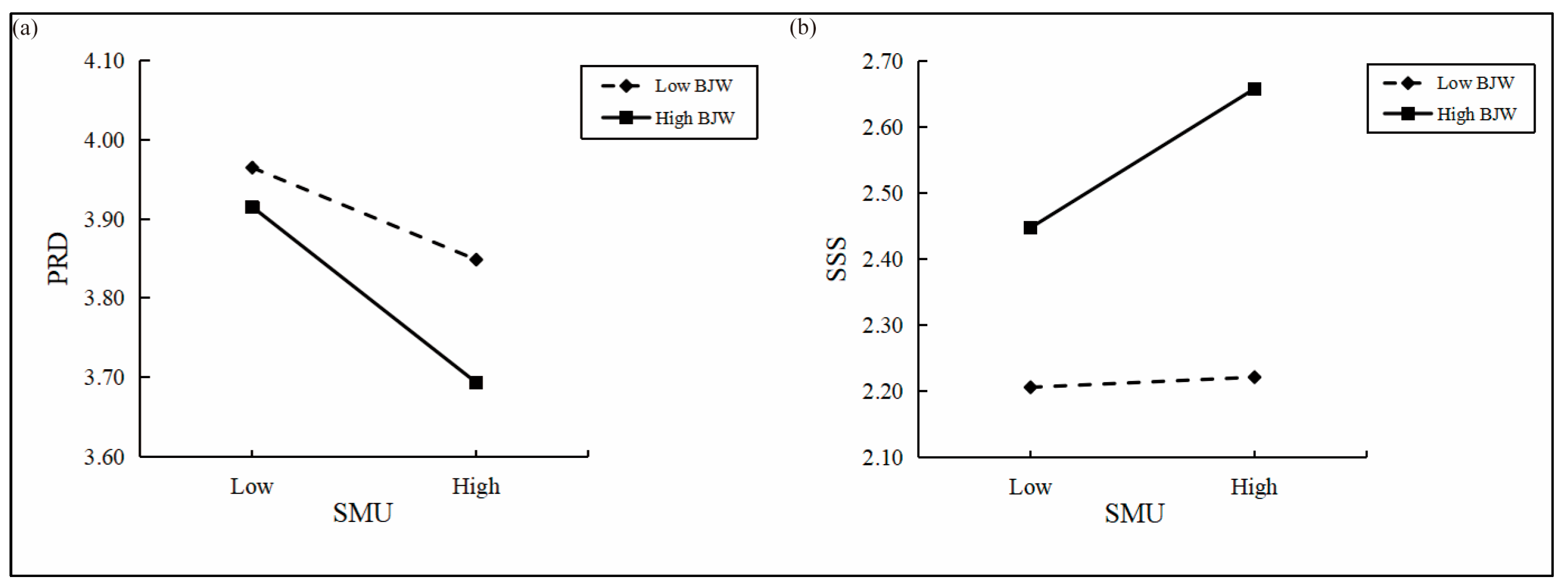

3.3. Moderation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Relationship Between Social Media Use and PRD

4.2. Mediating Role of Subjective Social Status

4.3. Moderating Role of Belief in a Just World

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PRD | Personal relative deprivation |

| SMU | Social media use |

| SSS | Subjective social status |

| BJW | Belief in a just world |

References

- Adler, N. E., Epel, E. S., Castellazzo, G., & Ickovics, J. R. (2000). Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy white women. Health Psychology, 19(6), 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alessandro, M., Lagomarsino, B. C., Scartascini, C., Streb, J., & Torrealday, J. (2021). Transparency and trust in government. Evidence from a survey experiment. World Development, 138, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Hassan, H., Nevo, D., & Wade, M. (2015). Linking dimensions of social media use to job performance: The role of social capital. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 24(2), 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaman, M. S. (2024). Patterns and trends of global social media censorship: Insights from 76 countries. International Communication Gazette, 87, 17480485241288768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, E. R., Matz, S. C., Youyou, W., & Iyengar, S. S. (2020). Authentic self-expression on social media is associated with greater subjective well-being. Nature Communications, 11(1), 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartholomaeus, J., Strelan, P., & Burns, N. (2024). Does the empowering function of the belief in a just world generalise? Broad-base cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. Social Justice Research, 37(1), 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, V., Hand, C., & Hartshorne, R. (2019). How compulsive use of social media affects performance: Insights from the UK by purpose of use. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(6), 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berryman, C., Ferguson, C. J., & Negy, C. (2018). Social media use and mental health among young adults. Psychiatric Quarterly, 89(2), 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beshai, S., Mishra, S., Meadows, T. J. S., Parmar, P., & Huang, V. (2017). Minding the gap: Subjective relative deprivation and depressive symptoms. Social Science and Medicine, 173, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brickman, P., & Bulman, R. J. (1977). Pleasure and pain in social comparison. In J. M. Suls, & R. L. Miller (Eds.), Social comparison processes: Theoretical and empirical perspectives (pp. 149–186). Hemisphere. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, M. J., Kim, H., Gheorghiu, A. I., & Matthews, W. J. (2017). The interrelations between social class, personal relative deprivation, and prosociality. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(6), 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callan, M. J., Shead, N. W., & Olson, J. M. (2011). Personal relative deprivation, delay discounting, and gambling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(5), 955–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y., & Fan, X. (2015). Discordance between subjective and objective social status in contemporary China. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 2(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center. (2025). The 55th statistical report on China’s internet development. Available online: https://cnnic.cn/n4/2025/0117/c208-11228.html (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Cho, J. (2014). Will social media use reduce relative deprivation? Systematic analysis of social capital’s mediating effects of connecting social media use with relative deprivation. International Journal of Communication, 8, 2811–2833. [Google Scholar]

- Crosby, F. (1976). Model of egotistical relative deprivation. Psychological Review, 83(2), 85–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucciniello, M., & Nasi, G. (2014). Transparency for trust in government: How effective is formal transparency? International Journal of Public Administration, 37(13), 911–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cyberspace Administration of China. (2024). The cyberspace administration of China has launched the 2024 “Qinglang” series of special campaigns. Available online: https://www.cac.gov.cn/2024-03/15/c_1712088026696264.htm (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalbert, C., & Filke, E. (2007). Belief in a personal just world, justice judgments, and their functions for prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(11), 1516–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eynon, R., Ulrike, D., & Malmberg, L.-E. (2018). Moving on up in the information society? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between internet use and social class mobility in Britain. The Information Society, 34(5), 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feather, N. T. (2015). Analyzing relative deprivation in relation to deservingness, entitlement and resentment. Social Justice Research, 28(1), 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnham, A. (2003). Belief in a just world: Research progress over the past decade. Personality and Individual Differences, 34(5), 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X., & Hou, Y. (2022). Patterns of achievement attribution of Chinese adults and their sociodemographic characteristics and psychological outcomes: A large-sample longitudinal study. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, A. Y. H., Hartanto, A., Kasturiratna, K. T. A. S., & Majeed, N. M. (2025). No consistent evidence for between- and within-person associations between objective social media screen time and body image dissatisfaction: Insights from a daily diary study. Social Media + Society, 11(1), 20563051251313855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greitemeyer, T., & Sagioglou, C. (2017). Increasing wealth inequality may increase interpersonal hostility: The relationship between personal relative deprivation and aggression. Journal of Social Psychology, 157(6), 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S., Lei, J., & Zhang, F. (2024). How social media social comparison influences Chinese adolescents’ flourishing: The mediation effects of identity processing styles. Child & Family Social Work. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafer, C. L., & Bègue, L. (2005). Experimental research on just-world theory: Problems, developments, and future challenges. Psychological Bulletin, 131(1), 128–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins-Guarnieri, M. A., Wright, S. L., & Johnson, B. (2013). Development and validation of a social media use integration scale. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2(1), 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. W., & Chock, T. M. (2015). Body image 2.0: Associations between social grooming on Facebook and body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiral Ucar, G., Hasta, D., & Kaynak Malatyali, M. (2019). The mediating role of perceived control and hopelessness in the relation between personal belief in a just world and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 143, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, P., & Kraft, B. (2023). Exploring the relationship between multiple dimensions of subjective socioeconomic status and self-reported physical and mental health: The mediating role of affect. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1138367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, M. J., & Miller, D. T. (1978). Just world research and attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85(5), 1030–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, C. S., Basu, D., & Chen, E. (2017). Just world beliefs are associated with lower levels of metabolic risk and inflammation and better sleep after an unfair event. Journal of Personality, 85(2), 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lilly, K. J., Sibley, C. G., & Osborne, D. (2023). Social media use does not increase individual-based relative deprivation: Evidence from a five-year RI-CLPM. Cyberpsychology-Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 17(5), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Nijkamp, P., & Lin, D. (2017). Urban-rural imbalance and tourism-led growth in China. Annals of Tourism Research, 64, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. S., Shteynberg, G., Morris, M. W., Yang, Q., & Galinsky, A. D. (2020). How does collectivism affect social interactions? A test of two competing accounts. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47(3), 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marengo, D., Montag, C., Sindermann, C., Elhai, J. D., & Settanni, M. (2021). Examining the links between active Facebook use, received likes, self-esteem and happiness: A study using objective social media data. Telematics and Informatics, 58, 101523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard, A., Baldassar, L., & Wilding, R. (2018). The significance of digital citizenship in the well-being of older migrants. Public Health, 158, 144–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadler, J., Day, M. V., Beshai, S., & Mishra, S. (2020). The relative deprivation trap: How feeling deprived relates to symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 39(10), 897–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, L., Niu, J., Bi, X., Yang, C., Liu, Z., Wu, Q., Ning, N., Liang, L., Liu, A., Hao, Y., Gao, L., & Liu, C. (2020). The impacts of knowledge, risk perception, emotion and information on citizens’ protective behaviors during the outbreak of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study in China. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nudelman, G. (2013). The belief in a just world and personality: A meta-analysis. Social Justice Research, 26(2), 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orehek, E., & Human, L. J. (2017). Self-expression on social media: Do tweets present accurate and positive portraits of impulsivity, self-esteem, and attachment style? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(1), 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostic, D., Qalati, S. A., Barbosa, B., Shah, S. M. M., Galvan Vela, E., Herzallah, A. M., & Liu, F. (2021). Effects of social media use on psychological well-being: A mediated model. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 678766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, C., & Zhao, M. (2024). How does upward social comparison impact the delay discounting: The chain mediation of belief in a just world and relative deprivation. Psychology in the Schools, 61(1), 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H. J., & Park, Y. B. (2024). Negative upward comparison and relative deprivation: Sequential mediators between social networking service usage and loneliness. Current Psychology, 43(10), 9141–9151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F. (2016). In pursuit of three theories: Authoritarianism, relative deprivation, and intergroup contact. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phongsavan, P., Chey, T., Bauman, A., Brooks, R., & Silove, D. (2006). Social capital, socio-economic status and psychological distress among Australian adults. Social Science and Medicine, 63(10), 2546–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivadeneira, M. F., Salvador, C., Araujo, L., Caicedo-Gallardo, J. D., Cóndor, J., Torres-Castillo, A. L., Miranda-Velasco, M. J., Dadaczynski, K., & Okan, O. (2023). Digital health literacy and subjective wellbeing in the context of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study among university students in Ecuador. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1052423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, M., Evans, O., & Wilkinson, R. B. (2016). A longitudinal study of the relations among university students’ subjective social status, social contact with university friends, and mental health and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 35(9), 722–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K., Kawakami, N., Yamaoka, K., Ishikawa, H., & Hashimoto, H. (2010). The impact of subjective and objective social status on psychological distress among men and women in Japan. Social Science and Medicine, 70(11), 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scardigno, R., Gambarrota, R., & Centonze, L. (2024). Social representation of mental health disorders in the Italian Big Brother Vip edition. Behavioral Sciences, 14(11), 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K. M., Al-Hamzawi, A. O., Andrade, L. H., Borges, G., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., Fiestas, F., Gureje, O., Hu, C., Karam, E. G., Kawakami, N., Lee, S., Levinson, D., Lim, C. C., Navarro-Mateu, F., Okoliyski, M., Posada-Villa, J., Torres, Y., Williams, D. R., Zakhozha, V., & Kessler, R. C. (2014). Associations between subjective social status and DSM-IV mental disorders: Results from the World Mental Health surveys. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(12), 1400–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh-Manoux, A., Marmot, M. G., & Adler, N. E. (2005). Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(6), 855–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., & Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(3), 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotaquirá, L., Backhaus, I., Sotaquirá, P., Pinilla-Roncancio, M., González-Uribe, C., Bernal, R., Galeano, J. J., Mejia, N., La Torre, G., Trujillo-Maza, E. M., Suárez, D. E., Duperly, J., & Ramirez Varela, A. (2022). Social capital and lifestyle impacts on mental health in university students in Colombia: An observational study. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 840292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W., Qian, G., Wang, X., Lei, L., Hu, Q., Chen, J., & Jiang, S. (2021). Mobile social media use and self-identity among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of friendship quality and the moderating role of gender. Current Psychology, 40(9), 4479–4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, R. G., & Pickett, K. E. (2007). The problems of relative deprivation: Why some societies do better than others. Social Science and Medicine, 65(9), 1965–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wills, T. A. (1981). Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 90(2), 245–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, M., & Hu, Z. (2022). Relative deprivation and depressive symptoms among Chinese migrant children: The impacts of self-esteem and belief in a just world. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1008370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H. (2020). Do SNSs really make us happy? The effects of writing and reading via SNSs on subjective well-being. Telematics and Informatics, 50, 101384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M., Tian, F., Cui, Q., & Wu, H. (2021). Prevalence and its associated factors of depressive symptoms among Chinese college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y. (2021). The role of online social capital in the relationship between internet use and self-worth. Current Psychology, 40(5), 2073–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Wei, L., Wang, J., & Zhang, W. (2024). Personal relative deprivation and moral self-judgments: The moderating role of sense of control. Journal of Research in Personality, 111, 104509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Tao, M. (2013). Relative deprivation and psychopathology of Chinese college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J., Yang, A., Jilili, M., Liu, L., & Feng, S. (2024). Media use and Chinese national social class identity: Based on the mediating effect of social capital. Current Psychology, 43(12), 10509–10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Yan, W., Tao, L., & Zhang, J. (2024). The association between relative deprivation, depression, and youth suicide: Evidence from a psychological autopsy study. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 89(4), 1691–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, H., Xiong, Q., & Xu, H. (2020). Does subjective social status predict self-rated health in Chinese adults and why? Social Indicators Research, 152(2), 443–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number of Participants (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18–35 | 955 | 38.14 |

| 36–59 | 1321 | 52.76 |

| ≥60 | 228 | 9.11 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1198 | 47.84 |

| Female | 1306 | 52.16 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 1903 | 76.00 |

| Unmarried | 601 | 24.00 |

| Education level | ||

| Primary school or below | 163 | 6.51 |

| Middle school | 1293 | 51.64 |

| College degree or above | 1048 | 41.85 |

| Annual family income | ||

| ≤CNY 60,000 | 555 | 22.16 |

| CNY 60,001–CNY 150,000 | 886 | 35.38 |

| ≥CNY 150,001 | 1063 | 42.45 |

| Social security status | ||

| With medical or pension insurance | 1910 | 76.28 |

| Without medical and pension insurance | 594 | 23.72 |

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social media use | 3.83 | 0.98 | 1 | |||

| 2. Personal relative deprivation | 3.85 | 0.78 | −0.257 *** | 1 | ||

| 3. Subjective social status | 2.39 | 0.87 | 0.153 *** | −0.498 *** | 1 | |

| 4. Belief in a just world | 4.17 | 1.06 | 0.138 *** | −0.193 *** | 0.224 *** | 1 |

| Path | B | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total effect | SMU → PRD | −0.117 | 0.018 | −6.474 | <0.001 | −0.152 | −0.081 |

| SMU → SSS | 0.072 | 0.021 | 3.453 | <0.001 | 0.031 | 0.113 | |

| SSS → PRD | −0.386 | 0.016 | −24.969 | <0.001 | −0.417 | −0.356 | |

| Direct effect | SMU → PRD | −0.089 | 0.016 | −5.498 | <0.001 | −0.121 | −0.057 |

| Indirect effect | SMU → SSS → PRD | −0.028 | 0.008 | −0.045 | −0.012 |

| Variables | PRD | SSS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | B | SE | t | p | |

| SMU | −0.086 | 0.016 | −5.328 | <0.001 | 0.058 | 0.021 | 2.805 | <0.01 |

| BJW | −0.048 | 0.013 | −3.774 | <0.001 | 0.160 | 0.016 | 10.040 | <0.001 |

| SSS | −0.374 | 0.016 | −23.771 | <0.001 | ||||

| SMU × BJW | −0.025 | 0.012 | −2.074 | <0.05 | 0.047 | 0.016 | 3.016 | <0.01 |

| Age | −0.002 | 0.001 | −1.265 | 0.206 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 5.307 | <0.001 |

| Gender | −0.108 | 0.026 | −4.195 | <0.001 | −0.110 | 0.033 | −3.337 | <0.001 |

| Marital status | −0.060 | 0.032 | −1.853 | 0.064 | 0.023 | 0.041 | 0.554 | 0.580 |

| Education level | −0.080 | 0.015 | −5.322 | <0.001 | 0.115 | 0.019 | 6.066 | <0.001 |

| Annual family income | −0.096 | 0.013 | −7.342 | <0.001 | 0.118 | 0.017 | 7.178 | <0.001 |

| Social security status | −0.040 | 0.031 | −1.300 | 0.194 | 0.057 | 0.039 | 1.435 | 0.152 |

| R2 | 0.322 | 0.121 | ||||||

| F | 118.254 | 38.288 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Zhao, X. Social Media Use and Personal Relative Deprivation Among Urban Residents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070962

Liu Y, Zhao X. Social Media Use and Personal Relative Deprivation Among Urban Residents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):962. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070962

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yihua, and Xiaoge Zhao. 2025. "Social Media Use and Personal Relative Deprivation Among Urban Residents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070962

APA StyleLiu, Y., & Zhao, X. (2025). Social Media Use and Personal Relative Deprivation Among Urban Residents in China: A Moderated Mediation Model. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 962. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070962