Me, My Child, and Us: A Group Parenting Intervention for Parents with Lived Experience of Psychosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

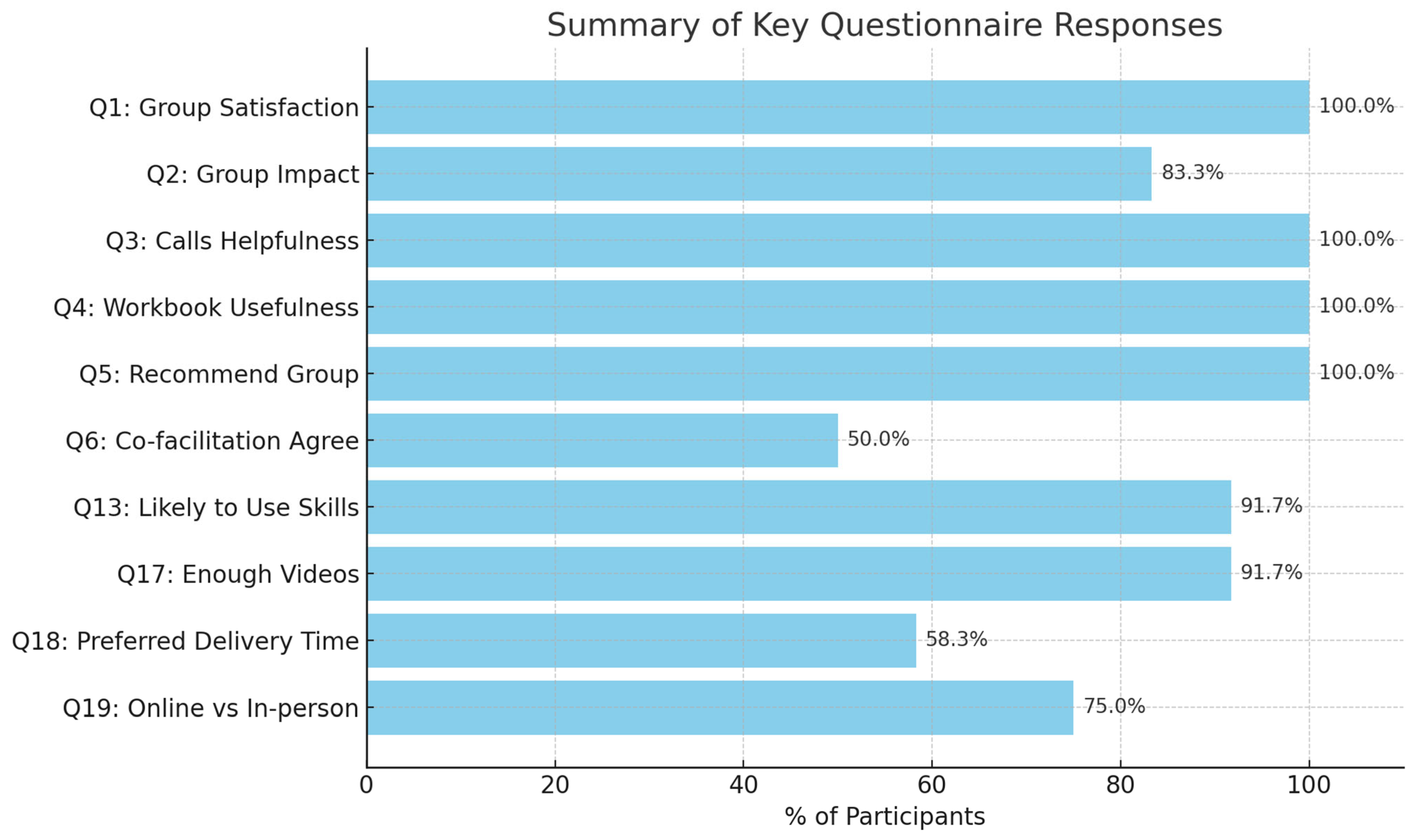

3.1. Acceptability and Feasibility of Me, My Child, and Us

3.2. Effectiveness of Me, My Child, and Us

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barkham, M., Bewick, B., Mullin, T., Gilbody, S., Connell, J., Cahill, J., Mellor-Clark, J., Richards, D., Unsworth, G., & Evans, C. (2013). The CORE-10: A short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 13(1), 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. O., & Jones, W. H. (1995). Parental stress scale (PSS). American Psychological Association (APA). [Google Scholar]

- Blegen, N. E., Hummelvoll, J. K., & Severinsson, E. (2012). Experiences of motherhood when suffering from mental illness: A hermeneutic study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 21(5), 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booij, S., Snippe, E., Jeronimus, B., Wichers, M., & Wigman, J. (2018). Affective reactivity to daily life stress: Relationship to positive psychotic and depressive symptoms in a general population sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 225, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüne, M. (2005). “Theory of mind” in schizophrenia: A review of the literature. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 31(1), 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci, S., Berry, N., Morris, R., Berry, K., Haddock, G., Lewis, S., & Edge, D. (2018). Remote delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy to people with psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 48(13), 2227–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camoirano, A. (2017). Mentalising makes parenting work: A review about parental reflective functioning and clinical interventions to improve it. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L. E., Hanlon, M. C., Galletly, C. A., Harvey, C., Stain, H., Cohen, M., van Ravenzwaaij, D., & Brown, S. (2018). Severity of illness and adaptive functioning predict quality of care of children among parents with psychosis: A confirmatory factor analysis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(5), 435–445. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Campbell, L. E., Hanlon, M. C., Poon, A. W. C., Paolini, S., Stone, M., Galletly, C., Stain, H. J., & Cohen, M. (2012). The experiences of Australian parents with psychosis: The second Australian national survey of psychosis. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(9), 890–900. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Dolman, C., Jones, I., & Howard, L. M. (2013). Pre-conception to parenting: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the qualitative literature on motherhood for women with severe mental illness. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(3), 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenson, E., Rhodes, J., Feigenbaum, J., & Solly, A. (2008). The experiences of fathers with psychosis. Journal of Mental Health, 17(6), 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozeh, N., Nazarenko, A., Alizon, F., & Daille, B. (2020). Keyword extraction: Issues and methods. Natural Language Engineering, 26(3), 259–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishburn, S. (2017). ‘Thinking about parenting’—The role of mind-mindedness and parental cognitions in parental behaviour and child developmental outcomes [Doctoral dissertation, University of York]. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P., & Bateman, A. W. (2016). Mentalizing and borderline personality disorder. American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (2006). The mentalization-focused approach to self pathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20(6), 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillard, S., Turner, K., Gibson, S., & Holley, J. (2015). Experiences of crisis care reported by service users and carers. Mental Health Review Journal, 20(4), 191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Grusec, J. E., & Davidov, M. (2010). Integrating different perspectives on socialisation theory and research: A domain-specific approach. Child Development, 81(3), 687–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, S. J., Lewin, J., Butler, S., Vaillancourt, K., & Seth-Smith, F. (2016). Affect recognition and the quality of mother-infant interaction: Understanding parenting difficulties in mothers with schizophrenia. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(1), 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, K., Smith, M., Wittkowski, A., & Varese, F. (2022). Recovery in parents with psychosis: A systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence. Psychiatry Research, 310, 114428. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, C., & Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18(2), 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, Y., & Jungbauer, J. (2014). Challenges and coping strategies of children with parents affected by schizophrenia: Results from an in-depth interview study. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 31(2), 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumm, S., Becker, T., & Wiegand-Grefe, S. (2013). Mental health services for parents affected by mental illness. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 26(4), 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luyten, P., Mayes, L. C., Nijssens, L., & Fonagy, P. (2017). The parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Development and preliminary validation. PLoS ONE, 12(5), e0176218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, M., Kumar, D., & Verma, R. (2015). Effect of psychosocial environment in children having mother with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research, 226(2-3), 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMullan, A. D., Lapierre, L. M., & Li, Y. (2018). A qualitative investigation of work-family-supportive coworker behaviors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 107, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, D. C., Burns, M. N., Schueller, S. M., Clarke, G., & Klinkman, M. (2013). Behavioral intervention technologies: Evidence review and recommendations for future research in mental health. General Hospital Psychiatry, 35(4), 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montag, C., Dziobek, I., Richter, I. S., Neuhaus, K., Lehmann, A., Sylla, R., Heekeren, H., Heinz, A., & Gallinat, J. (2010). Different aspects of theory of mind in paranoid schizophrenia: Evidence from a video-based assessment. Psychiatry Research, 186, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montag, C., Haase, L., Seidel, D., Bayerl, M., Gallinat, J., Herrmann, U., & Dannecker, K. (2014). A pilot RCT of psychodynamic group art therapy for patients in acute psychotic episodes: Feasibility, impact on symptoms and mentalising capacity. PLoS ONE, 9(11), e112348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, P., Mossey, S., Bailey, P., & Forchuk, C. (2011). Mothers with serious mental illness: Their experience of “hitting bottom”. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2011, 708318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nærde, A., & Sommer Hukkelberg, S. (2020). An examination of validity and reliability of the Parental Stress Scale in a population based sample of Norwegian parents. PLoS ONE, 15(12), e0242735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, J., & Miller, L. (2008). Parenting. In K. T. Mueser, & Jeste D. V. (Eds.), Clinical handbook of schizophrenia (pp. 471–480). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pajulo, M., Tolvanen, M., Karlsson, L., Halme-Chowdhury, E., Öst, C., Luyten, P., Mayes, L., & Karlsson, H. (2015). The prenatal parental reflective functioning questionnaire: Exploring factor structure and construct validity of a new measure in the Finn brain birth cohort pilot study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(4), 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J., Vickers, K., Atkinson, L., Gonzalez, A., Wekerle, C., & Levitan, R. (2012). Parenting stress mediates between maternal maltreatment history and maternal sensitivity in a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(5), 433–437. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R. C. (1992). Child-parent relationship scale. Journal of Early Childhood and Infant Psychology, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, J., Barlow, J., & Johns, L. (2021). Mental health professionals’ experiences of working with parents with psychosis and their families: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, J., Barlow, J., & Johns, L. C. (2022a). Parenting and psychosis: An experience sampling methodology study investigating the inter-relationship between stress from parenting and positive psychotic symptoms. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 1236–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radley, J., Barlow, J., & Johns, L. C. (2022b). Sociodemographic characteristics associated with parenthood amongst patients with a psychotic diagnosis: A cross-sectional study using patient clinical records. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57, 1897–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, J., Barlow, J., & Johns, L. C. (2022c). The needs and experiences of parents with psychosis: A qualitative interview study. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32, 2431–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, J., Barlow, J., & Johns, L. C. (2022d). A family perspective on parental psychosis: An interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96, 347–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radley, J., Sivarajah, N., Moltrecht, B., Klampe, M. L., Hudson, F., Delahay, R., Barlow, J., & Johns, L. C. (2022e). A scoping review of interventions designed to support parents with mental illness that would be appropriate for parents with psychosis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reupert, A., Maybery, D., Nicholson, J., Göpfert, M., & Seeman, M. V. (Eds.). (2015). Parental psychiatric disorder: Distressed parents and their families (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reupert, A. E., & Maybery, D. J. (2009). A “snapshot” of Australian programs to support children and adolescents whose parents have a mental illness. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 33(2), 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi, A. J., Sinkule, J., & Spring, M. (2010). Designing websites for persons with cognitive deficits: Design and usability evaluation. Technology and Disability, 22(1–2), 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schrank, B., Moran, K., Borghi, C., & Priebe, S. (2015). How to support patients with severe mental illness in their parenting role with children aged over 1 year? A systematic review of interventions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(12), 1765–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeman, M. V. (2002). Women with schizophrenia as parents. Primary Psychiatry, 9(10), 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, C., & Fonagy, P. (2008). The parent’s capacity to treat the child as a psychological agent: Constructs, measures and implications for developmental psychopathology. Social Development, 17(3), 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S. C., Connelly, M., Cross, W., & Stansfield, J. (2016). Peer support groups for parents with mental illness: A systematic review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(9–10), 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleed, M., Fearon, P., Martin, P., Midgley, N., & McFarquhar, T. (2021). The supporting parents project (SPP): Randomized controlled trial and implementation process study of the lighthouse parenting programme (LPP). The Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families. [Google Scholar]

- Sprong, M., Schothorst, P., Vos, E., Hox, J., & Van Engeland, H. (2007). Theory of mind in schizophrenia: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, J., Boström, P., & Grip, K. (2020). Parents’ descriptions of how their psychosis affects parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, J., & Meyersson, N. (2020). Parents with psychosis and their children: Experiences of Beardslee’s intervention. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(5), 908–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strand, J., & Rudolfsson, L. (2020). Mental health professionals’ perceptions of parenting by service users with psychosis. Community Mental Health Journal, 56(6), 1014–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, A., Mellotte, H., Hardy, A., Peters, E., Keen, N., & Kane, F. (2022). The digital divide: Factors impacting on uptake of remote therapy in a South London psychological therapy service for people with psychosis. Journal of Mental Health, 31(6), 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wied, C. C., & Jansen, L. (2002). The stress-vulnerability hypothesis in psychotic disorders: Focus on the stress response systems. Current Psychiatry Reports, 4(3), 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenden, L., Calam, R., Drake, R. J., & Gregg, L. (2022). The Triple P positive parenting program for parents with psychosis: A case series with qualitative evaluation. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 791294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gender | Age | Ethnicity | No. of Children | Children’s Ages | Number of Sessions Attended |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 36–45 | PoGM | 1 | 6 | 2 |

| Female | 36–45 | PoGM | 1 | 3 | 8 |

| Female | >45 | White British | 1 | 15 | 8 |

| Female | >45 | White British | 1 | 10 | 7 |

| Female | 36–45 | White British | 3 | 11, 9, 3 | 8 |

| Female | >45 | White British | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Female | >45 | White British | 2 | 8, 12 | 7 |

| Female | 36–45 | White British | 4 | 8, 12, 15, 17 | 8 |

| Male | 26–35 | White British | 4 | 8, 5, 2, 3 | 6 |

| Female | 26–35 | PoGM | 3 | 13, 11, 8 | 6 |

| Male | >50 | White British | 2 | 16, 4 | 2 |

| Female | 26–35 | White British | 2 | 6, 5 | 5 |

| Female | 36–45 | PoGM | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| Name of Measure | Function | Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation, CORE-10, (Barkham et al., 2013) | Assesses distress and functioning. | Ten-item questionnaire. Scores are presented as a total score of 0–40 and a mean score of 0–4. Higher scores indicate higher levels of general psychological distress. A total score of 11 or above indicates clinical significance. It has an internal reliability (alpha) of 0.9 |

| Being a Parent Scale, BAPS, (Gibaud-Wallson & Wandersmith, 1978 as cited in Johnston & Mash, 1989) | Assesses parental self-efficacy and satisfaction regarding their parenting experiences. | Sixteen-item questionnaire with a 6-point Likert-type scale, which parents use to answer the extent to which they agree or disagree with statements about their parenting experiences. Scores range from 16 to 96. Scores are divided into satisfaction and efficacy, with lower scores indicating higher efficacy and satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.75 for satisfaction scale and 0.76 for efficacy scale are reported for reliability. |

| Child–parent Relationship Scale (Pianta, 1992) | Assesses parent–child relationship. | Fifteen-item questionnaire with a 5-point Likert scale. Each item is made up of 2 statements (30 statements in total), reflecting both positive and negative aspects of parent–child relationships. Ratings are clustered into two groups conflict and closeness. Lower scores on the conflict questions indicate more positive experiences, and higher scores for closeness questions indicate more positive experiences. Studies typically find good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha values typically ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 for both the Closeness and Conflict subscales. |

| The Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire, PRFQ (Luyten et al., 2017) | Assesses parents’ capacity to mentalize about and reflect on their actual and evolving relationship with their child(ren), including the parent’s understanding, curiosity about or disavowal of mental states, and the relationship between mental states and behavior. | Eighteen-item questionnaire rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The questionnaire consists of three subscales. Scores range from 18 to 126. There are three subscales, each consist of 6 items and are rated on a 7-point Likert scale. The PRFQ has good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.688, 0.772 and 0.745 per respective subscale). For the pre-mentalizing subscale, higher scores indicate lower levels of parental reflective functioning. For the certainty and interest/curiosity subscales, average scores are considered optimal. |

| Parental Stress Scale (Berry & Jones, 1995) | Assesses parents’ stress levels associated with child-rearing. It focuses on parents’ perceptions of their parental role rather than on the sources of stress themselves. | An 18-item measure. Scores range from 18 to 90, where higher scores indicate higher stress levels. Acceptable reliability ratings are reported cross-culturally (Nærde & Sommer Hukkelberg, 2020). |

| Session Number | Topic Discussed |

|---|---|

| One Two | Background to Parenting (as seen in Family Talk, Let’s Talk about children, CHIMPS, Kids Time, Triple P, Beardslee’s preventive family intervention and VIA family): understanding psychosis and the relationship between psychosis and parenting. Mentalization (as seen in the Lighthouse Parenting Programme and Turning into kids): improving mentalization (reflective functioning) and gaining a better understanding of children’s needs. |

| Three | Attunement (as seen in the Lighthouse Parenting Programme and Turning into kids): learning to better engage with children and learning to better respond to children. |

| Four | Communication (as seen in Beardslee’s preventive family intervention, Let’s talk about children, Kids Time, Family Talk and Think Family Whole Family Programme): assertiveness techniques and using encouragement, praise, and rewards. |

| Five | Managing Conflict and Setting Boundaries (as seen in Think Family Whole Family, Triple P and the Parenting Internet Intervention). |

| Six | Managing Symptoms of Psychosis (components of parental wellbeing or self-care is included in interventions such as CHIMPS Intervention): understanding symptoms of psychosis and learning coping strategies. |

| Seven | Communication about Psychosis with Children (as seen in Behavioral Family Therapy, Family Talk, CHIMPS Intervention, Child Talks, Kids Time, Triple P, and CHIMPS): myth busting fears about talking to children about psychosis, exploring what language to use and how to be age appropriate when speaking to children about psychosis, and considering what resources to use when talking to children about psychosis. |

| Eight | Planning for the Future: reflecting on learning, consolidating learning, and planning on how to maintain the use of newly learned skills and techniques. |

| Theme | Description | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Positive parenting changes | Increased attentiveness, improved emotional regulation, and strengthened relationships with children. | “I listen to them more… they seem to want to talk to me more.” |

| “I have become more assertive… able to set boundaries better. | ||

| Enhanced Understanding and Confidence | Greater self-awareness and confidence as a parent; application of parenting techniques. | “I am a lot more aware of my own emotions now… this helps me to mentalize my children better.” |

| Social Connection & Empowerment | Feeling supported and less isolated; benefits of sharing experiences with peers. | “It felt really empowering… to hear about similar experiences.” |

| “Being in a group with other parents made me feel less lonely.” | ||

| Course Design & Delivery | Appreciation of structure, balance, and content (videos, discussion, relaxation, etc.). | “It was a really good course… I wouldn’t change anything.” |

| Suggestions for expansion | Requests for similar groups focusing on psychosis alone; desire for broader access. | “I would like GPs and social services to be aware of this course.” |

| Overall Experience | Highly positive reflections; described as transformative and valuable. | “It’s been the best group I have been to.” |

| “Perfect intervention for me.” |

| Outcome | Pre-Test | Post-Test | Post–Pre | Post-/Pre-Change | t-Value | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SE) | Mean (SE) | Mean | % | |||

| CORE-10 (psychological distress scores) | 14.09 (2.97) | 2.82 (1.53) | −11.27 | −80.00 | 4.70 | 0.001 |

| Being a Parent Scale | ||||||

| Satisfaction Scale | 31.09 (1.95) | 45.27 (2.63) | 14.18 | 45.61 | −7.05 | 0.001 |

| Efficacy Scale | 28.00 (2.05) | 38.45 (0.99) | 10.45 | 37.34 | −6.52 | 0.001 |

| Child–parent Relationship Scale | ||||||

| Conflicts Scores | 34.27 (3.48) | 16.55 (1.20) | −17.73 | −51.72 | 6.56 | 0.001 |

| Positive aspects of relationship (closeness) | 39.55 (1.73) | 45.82 (1.01) | 6.27 | 15.86 | −4.28 | 0.001 |

| Dependence Scores | 10.18 (0.69) | 8.91 (0.49) | −1.27 | −12.50 | 2.01 | 0.1055 |

| The parental reflective functioning scale | ||||||

| Pre-Mentalizing Modes | 2.94 (0.42) | 1.09 (0.08) | −1.85 | −62.89 | 4.38 | 0.001 |

| Certainty about Mental States | 3.39 (0.47) | 5.65 (0.14) | 2.26 | 66.52 | −5.23 | 0.0015 |

| Interest and Curiosity in Mental States | 5.30 (0.47) | 7.00 (0.00) | 1.70 | 32.00 | −3.64 | 0.001 |

| Parental Stress Scale | 50.82 (3.54) | 23.64 (1.52) | −27.18 | −53.49 | 8.24 | 0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sivarajah, N.; Radley, J.; Knowles-Bevis, R.; Johns, L.C. Me, My Child, and Us: A Group Parenting Intervention for Parents with Lived Experience of Psychosis. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070950

Sivarajah N, Radley J, Knowles-Bevis R, Johns LC. Me, My Child, and Us: A Group Parenting Intervention for Parents with Lived Experience of Psychosis. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):950. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070950

Chicago/Turabian StyleSivarajah, Nithura, Jessica Radley, Rebecca Knowles-Bevis, and Louise C. Johns. 2025. "Me, My Child, and Us: A Group Parenting Intervention for Parents with Lived Experience of Psychosis" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070950

APA StyleSivarajah, N., Radley, J., Knowles-Bevis, R., & Johns, L. C. (2025). Me, My Child, and Us: A Group Parenting Intervention for Parents with Lived Experience of Psychosis. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070950