Can Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership Foster Employees’ Green Voice Behavior? A Moderated Mediation Model of Psychological Empowerment, Ecological Reflexivity, and Value Congruence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundation and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Underlying Theory

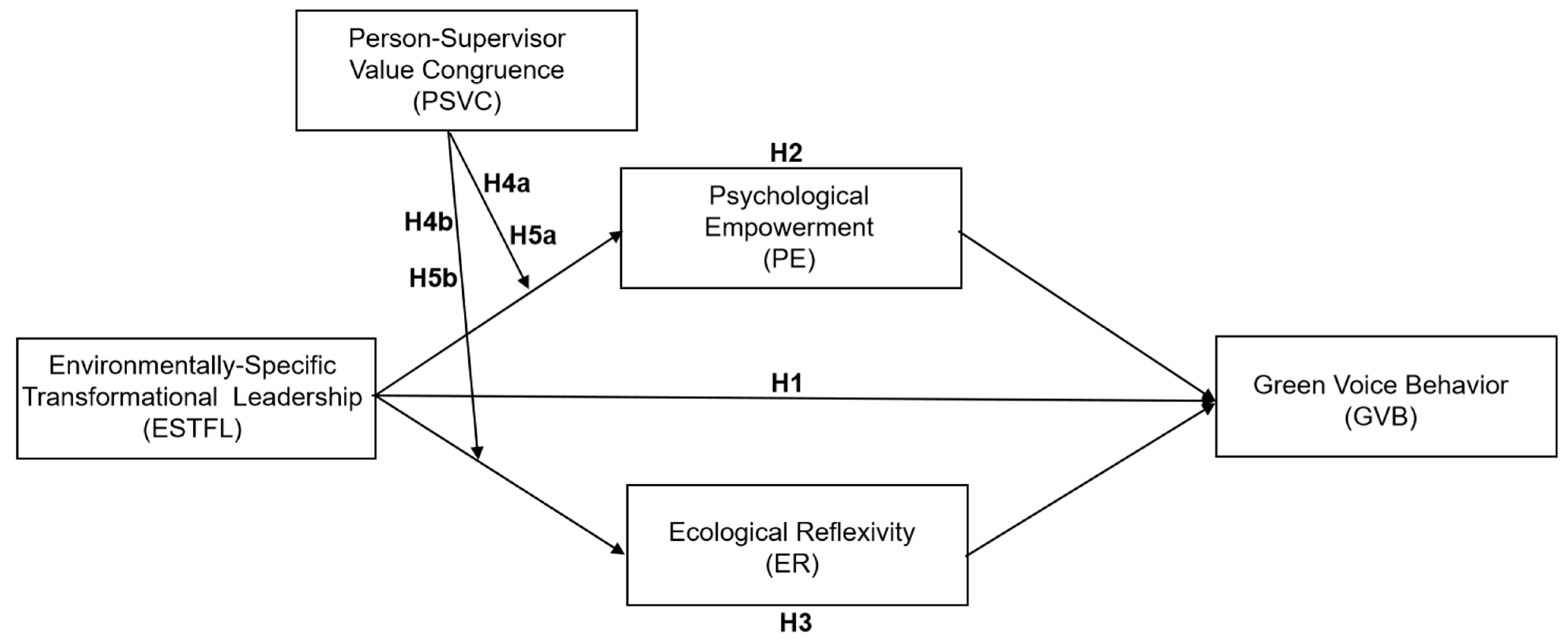

2.2. Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership and Green Voice Behavior

2.3. The Mediating Role of Psychological Empowerment

2.4. The Mediating Role of Ecological Reflexivity

2.5. The Moderating Roles of Person-Supervisor Value Congruence

3. Research Method

3.1. Procedures

3.2. Participants

3.3. Measures

3.3.1. Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership

3.3.2. Green Voice Behavior

3.3.3. Psychological Empowerment

3.3.4. Person-Supervisor Value Congruence

3.3.5. Ecological Reflexivity

3.3.6. Control Variables

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

4.4. Hypotheses Testing

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aboramadan, M., Barbar, J., Alhabil, W., & Alhalbusi, H. (2023). Green servant leadership and green voice behavior in Qatari higher education: Does climate for green initiative matter? International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 25(3), 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboramadan, M., Kundi, Y. M., & Becker, A. (2021). Green human resource management in nonprofit organizations: Effects on employee green behavior and the role of perceived green organizational support. Personnel Review, 51(7), 1788–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B., Maqsoom, A., Shahjehan, A., Afridi, S. A., Nawaz, A., & Fazliani, H. (2020). Responsible leadership and employee’s proenvironmental behavior: The role of organizational commitment, green shared vision, and internal environmental locus of control. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(1), 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsar, B., Shahjehan, A., & Shah, I. (2018). Leadership and employee pro-environmental behaviours. In Research handbook on employee pro-environmental behaviour. Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, M. W., Karatepe, O. M., Syed, F., & Husnain, M. (2022). Leader knowledge hiding, feedback avoidance and hotel employee outcomes: A moderated mediation model. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(2), 578–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwheshi, A., Alzubi, A., & Iyiola, K. (2024). Linking responsible leadership to organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: Examining the role of employees harmonious environmental passion and environmental transformational leadership. Sage Open, 14(3), 21582440241271177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, E., Karatepe, O. M., Rezapouraghdam, H., & Avci, T. (2020). A conceptual model for green human resource management: Indicators, differential pathways, and multiple pro-environmental outcomes. Sustainability, 12(17), 7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astakhova, M. N. (2016). Explaining the effects of perceived person-supervisor fit and person-organization fit on organizational commitment in the U.S. and Japan. Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 956–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avolio, B. J., Zhu, W., Koh, W., & Bhatia, P. (2004). Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: Mediating role of psychological empowerment and moderating role of structural distance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(8), 951–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1991). The full range of leadership development: Basic and advanced manuals. Bass, Avolio and Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Boiral, O., Talbot, D., & Paille, P. (2015). Leading by Example: A Model of Organizational Citizenship Behavior for the Environment. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(6), 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis, & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of crosscultural psychology: Methodology (Vol. 2, pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2009). Leader–follower values congruence: Are socialized charismatic leaders better able to achieve it? Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S., & Chang, C.-H. (2013). The determinants of green product development performance: Green dynamic capabilities, green transformational leadership, and green creativity. Journal of Business Ethics, 116(1), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K., Wei, F., & Lin, Y. (2019). The trickle-down effect of responsible leadership on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Research, 102, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y., Liu, H., Yuan, Y., Zhang, Z., & Zhao, J. (2022). What makes employees green advocates? Exploring the effects of green human resource management. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), VII–XVI. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, S. Y., & Barron, K. (2016). Employee voice behavior revisited: Its forms and antecedents. Management Research Review, 39(12), 1720–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conger, J. A., & Kanungo, R. N. (1988). The empowerment process: Integrating theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crucke, S., Servaes, M., Kluijtmans, T., Mertens, S., & Schollaert, E. (2022). Linking environmentally-specific transformational leadership and employees’ green advocacy: The influence of leadership integrity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(2), 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B. F., Bishop, J. W., & Govindarajulu, N. (2009). A conceptual model for organizational citizenship behavior directed toward the environment. Business & Society, 48(2), 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Dreu, C. K. W. (2007). Cooperative outcome interdependence, task reflexivity, and team effectiveness: A motivated information processing perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Jong, B. A., & Elfring, T. (2010). How does trust affect the performance of ongoing teams? The mediating role of reflexivity, monitoring, and effort. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H., Su, W., & Hahn, J. (2023). How green transformational leadership affects employee individual green performance—A multilevel moderated mediation model. Behavioral Science, 13(11), 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J., Li, C., Xu, Y., & Wu, C. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee voice behavior: A Pygmalion mechanism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(5), 650–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaied, M. M. (2020). A moderated mediation model for the relationship between inclusive leadership and job embeddedness. American Journal of Business, 35(3–4), 191–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enninga, J., & Yonk, R. M. (2023). Achieving ecological reflexivity: The limits of deliberation and the alternative of free-market-environmentalism. Sustainability, 15(8), 6396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., Kraimer, M. L., & Liden, R. C. (2004). Work value congruence and intrinsic career success: The compensatory roles of leader-member exchange and perceived organizational support. Personnel Psychology, 57(2), 305–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., Chen, L., Song, L. J., & Zheng, X. (2021). How LMX differentiation attenuates the influence of ethical leadership on workplace deviance: The mediating role of psychological empowerment. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 693557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurmani, J. K., Khan, N. U., Khalique, M., Yasir, M., Obaid, A., & Sabri, N. A. A. (2021). Do environmental transformational leadership predicts organizational citizenship behavior towards environment in hospitality industry: Using structural equation modelling approach. Sustainability, 13(10), 5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (pp. xvii, 507). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, P., Zhou, H., Jiang, C., Anand, A., & Zhou, Q. (2024). Responsible leadership and deceptive knowledge hiding: The mediating role of moral reflectiveness and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Knowledge Management, 29(1), 49–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, B. J., Bynum, B. H., Piccolo, R. F., & Sutton, A. W. (2011). Person-organization value congruence: How transformational leaders influence work group effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 54(4), 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. H. (1997). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, D., & Albrecht, C. (2013). The worldwide academic field of business ethics: Scholars’ perceptions of the most important issues. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(4), 777–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S., Ghardallou, W., Dong, R. K., Li, R. Y. M., & Nazeer, S. (2025). From ethical leadership to green voice: A pathway to organizational sustainability. Acta Psychologica, 257, 105116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y., Zhu, L., Zhou, M., Li, J., Maguire, P., Sun, H., & Wang, D. (2018). Exploring the influence of ethical leadership on voice behavior: How leader-member exchange, psychological safety and psychological empowerment influence employees’ willingness to speak out. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C. Y., Kang, S.-W., & Choi, S. B. (2023). Coaching leadership and creative performance: A serial mediation model of psychological empowerment and constructive voice behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1077594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyas, S., Abid, G., Ashfaq, F., Ali, M., & Ali, W. (2021). Status Quos Are Made to be Broken: The Roles of Transformational Leadership, Job Satisfaction, Psychological Empowerment, and Voice Behavior. SAGE Open, 11(2), 21582440211006734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, R., Shahzad, K., & Donia, M. B. L. (2023). Environmentally specific transformational leadership and employee green attitude and behavior: An affective events theory perspective. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 92, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, U. T., Andersen, L. B., & Jacobsen, C. B. (2019). Only when we agree! how value congruence moderates the impact of goal-oriented leadership on public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 79(1), 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeung, C.-W., & Yoon, H. J. (2018). When leadership elicits voice: Evidence for a mediated moderation model. Journal of Management & Organization, 24(1), 40–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. N., & Khan, N. A. (2022). The nexuses between transformational leadership and employee green organisational citizenship behaviour: Role of environmental attitude and green dedication. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(3), 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A. S., Du, J., Ali, M., Saleem, S., & Usman, M. (2019). Interrelations between ethical leadership, green psychological climate, and organizational environmental citizenship behavior: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A., Kim, Y., Han, K., Jackson, S. E., & Ployhart, R. E. (2017). Multilevel influences on voluntary workplace green behavior: Individual differences, leader behavior, and coworker advocacy. Journal of Management, 43(5), 1335–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E., & Onghena, P. (2014). The integration of work and learning: Tackling the complexity with structural equation modelling. In Discourses on professional learning (pp. 255–291). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y., Qu, X., & Xia, Y. (2020). The influence of servant leadership on employee creativity: The mediating role of knowledge sharing behavior and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Human Resources Development of China, 37(11), 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, D. C., Liu, J., & Fu, P. P. (2007). Feeling trusted by business leaders in China: Antecedents and the mediating role of value congruence. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(3), 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader-follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J. A., Piccolo, R. F., Jackson, C. L., Mathieu, J. E., & Saul, J. R. (2008). A meta-analysis of teamwork processes: Tests of a multidimensional model and relationships with team effectiveness criteria. Personnel Psychology, 61(2), 273–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C., & Xu, S. (2019). Management and organization theories. Peking University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, H., Ferris, D. L., & Brown, D. J. (2012). Does power distance exacerbate or mitigate the effects of abusive supervision? It depends on the outcome. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.-L., Chang, H.-F., Ko, M.-H., & Lin, C.-W. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee voices in the hospitality industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Wu, M., & Chen, X. (2023). A chain mediation model of inclusive leadership and voice behavior among university teachers: Evidence from China. Scientific Reports (Nature Publisher Group), 13(1), 22377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F., & Qi, M. (2022). Enhancing organizational citizenship behaviors for the environment: Integrating social identity and social exchange perspectives. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 1901–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J., Liu, J., & Wang, Y. (2024). How to inspire green creativity among Gen Z hotel employees: An investigation of the cross-level effect of green organizational climate. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 33(2), 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Zhu, R., & Yang, Y. (2010). I warn you because I like you: Voice behavior, employee identifications, and transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X., & Yu, X. (2023). Green transformational leadership and employee organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in the manufacturing industry: A social information processing perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1097655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Guo, Y., Zhang, M., & Ma, G. (2024). Can green human resource management promote employee green advocacy? The mediating role of green passion and the moderating role of supervisory support for the environment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(1), 121–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Li, Y., Guo, Y., Zhang, M., & Ramsey, T. (2025). Does green human resource management foster green advocacy? A perspective of conservation of resources theory. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 38(2), 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Liao, J., Guo, Y., Zhang, M., & Wang, X. (2023). The effect of corporate social responsibility on unethical pro-organizational behavior: The mediation of moral identity and moderation of supervisor-employee value congruence. Current Psychology, 42(17), 14283–14296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luu, T. T. (2024). How and when to activate hospitality employees’ organizational citizenship behavior for the environment in South Korea and Vietnam. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(1), 151–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., & Ma, Q. (2024). Influence mechanism of environmentally transformational leadership on organizational citizenship behavior for the environment: A moderated mediation model. Current Psychology, 43(11), 9540–9552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D. P., Coxe, S., & Baraldi, A. N. (2012). Guidelines for the investigation of mediating variables in business research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 27(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, K., Conway, E., Fu, N., Bailey, K., Kelly, G., & Hannon, E. (2016). Enhancing knowledge exchange and combination through HR practices: Reflexivity as a translation process. Human Resource Management Journal, 26(3), 304–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W. (2011). Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E. W., & Milliken, F. J. (2000). Organizational silence: A barrier to change and development in a pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mughal, M. F., Li Cai, S., Faraz, N. A., & Ahmed, F. (2022). Environmentally specific servant leadership and employees’ pro-environmental behavior: Mediating role of green self efficacy. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, A., Mahmood, S., Naeem, M., & Khan, K. I. (2025). I feel green with my leader: When and how green transformational leadership influences employees’ green behavior. International Journal of Ethics and Systems. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Ramos, L., Huertas-Valdivia, I., & García-Muiña, F. E. (2024). Green human resource management in hospitality: Nurturing green voice behaviors through passion and mindfulness. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 33(6), 784–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeer, S., Naveed, S., Sair, S. A., & Khan, K. (2025). Making sustainable voices heard at the workplace. International Journal of Ethics and Systems. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A. A., Abdelall, H. A., & Ali, H. I. (2025). Enhancing nurses’ sustainability consciousness and its effect on green behavior intention and green advocacy: Quasi-experimental study. BMC Nursing, 24(1), 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y., Tian, J., Zhou, X., & Wu, L. (2023). How and when does leader humility promote followers’ proactive customer service performance? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(5), 1585–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J. (2019). Ecological reflexivity: Characterising an elusive virtue for governance in the Anthropocene. Environmental Politics, 28(7), 1145–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priatna, D. K., Farooq, K., Yusliza, M. Y., Muhammad, Z., Alkaf, A. R., & Siswanti, I. (2025). Employee ecological behavior through green transformational leadership: The mediating role of green HRM practices and green organizational climate. Journal of Management Development, 44(3), 348–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, C., Chatterjee, N., Srivastava, N. K., & Dubey, R. K. (2023). Achieving organizational environmental citizenship behavior through green transformational leadership: A moderated mediation study. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 17(6), 1088–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramus, C. A., & Steger, U. (2000). The roles of Supervisory support behaviors and environmental policy in employee “ecoinitiatives” at leading-edge european companies. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 605–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S., & Robert, C. (2010). Differential effects of empowering leadership on in-role and extra-role employee behaviors: Exploring the role of psychological empowerment and power values. Human Relations, 63(11), 1743–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, S., & Robert, C. (2013). Empowerment, organizational commitment, and voice behavior in the hospitality industry: Evidence from a multinational sample. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 54(2), 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D. W. S., Redman, T., & Maguire, S. (2013). Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietze, S., & Schölmerich, F. (2025). How green transformational leadership and psychological empowerment impact green voice behavior. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2025(1), 14203. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, J. L. (2018). The nature, measurement and nomological network of environmentally specific transformational leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 961–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. L., & Barling, J. (2013). Greening organizations through leaders’ influence on employees’ pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(2), 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J. L., & Carleton, E. (2018). Uncovering how and when environmental leadership affects employees’ voluntary pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(2), 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schermuly, C. C., Creon, L., Gerlach, P., Graßmann, C., & Koch, J. (2022). Leadership styles and psychological empowerment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 29(1), 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M. C., Den Hartog, D. N., & Koopman, P. L. (2007). Reflexivity in teams: A measure and correlates. Applied Psychology, 56(2), 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M. C., Den Hartog, D. N., Koopman, P. L., & van Knippenberg, D. (2008). The role of transformational leadership in enhancing team reflexivity. Human Relations, 61(11), 1593–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, M. C., Homan, A. C., & van Knippenberg, D. (2013). To reflect or not to reflect: Prior team performance as a boundary condition of the effects of reflexivity on learning and final team performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(1), 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibert, S. E., Wang, G., & Courtright, S. H. (2011). Antecedents and consequences of psychological and team empowerment in organizations: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(5), 981–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S. H. A., Cheema, S., Al-Ghazali, B. M., Ali, M., & Rafiq, N. (2021). Perceived corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behaviors: The role of organizational identification and coworker pro-environmental advocacy. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simola, S. K., Barling, J., & Turner, N. (2010). Transformational leadership and leader moral orientation: Contrasting an ethic of justice and an ethic of care. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(1), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. The Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M. (1996). Social structural characteristics of psychological empowerment. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G. M., Kizilos, M. A., & Nason, S. W. (1997). A Dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness satisfaction, and strain. Journal of Management, 23(5), 679–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S., & Singh, L. B. (2023). Role of inclusive leadership in employees’ OCB in hospitality industry: A social cognitive perspective. Journal of Management Development, 42(7/8), 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. W., & Velthouse, B. A. (1990). Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 666–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41(1), 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Guan, C., Cui, T., Cai, S., & Liu, D. (2021). Servant leadership, team reflexivity, coworker support climate, and employee creativity: A multilevel perspective. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 28(4), 465–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Xu, H., & Liu, Y. (2018). How does ethical leadership trickle down? Test of an integrative dual-process model. Journal of Business Ethics, 153(3), 691–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S., & Liu, H. (2022). Research on energy conservation and carbon emission reduction effects and mechanism: Quasi-experimental evidence from China. Energy Policy, 169, 113180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, D. M. (2010). Outcome expectancy and self-efficacy: Theoretical implications of an unresolved contradiction. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(4), 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, N., Guo, T., & Zhang, L. (2024). How CEO transformational leadership affects business model innovation: A serial moderated mediation model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 39(4), 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L., Men, C., & Ci, X. (2023). Linking perceived ethical leadership to workplace cheating behavior: A moderated mediation model of moral identity and leader-follower value congruence. Current Psychology, 42(26), 22265–22277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, W. M. A., & Yaqub, M. Z. (2024). The prolificacy of green transformational leadership in shaping employee green behavior during times of crises in small and medium enterprises: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1258990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Akhtar, M. N., Zhang, Y., Tang, J., & Yang, Q. (2024). How and when supervisor bottom-line mentality affects employees’ voluntary workplace green behaviors: A goal-shielding perspective. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(6), 5357–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Ul-Durar, S., Akhtar, M. N., Zhang, Y., & Lu, L. (2021). How does responsible leadership affect employees’ voluntary workplace green behaviors? A multilevel dual process model of voluntary workplace green behaviors. Journal of Environmental Management, 296, 113205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Bartol, K. M. (2010). Linking empowering leadership and employee creativity: The influence of psychological empowerment, intrinsic motivation, and creative process engagement. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Zhou, Q., He, P., & Jiang, C. (2021). How and when does socially responsible hrm affect employees’ organizational citizenship behaviors toward the environment? Journal of Business Ethics, 169(2), 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Graham, L., Epitropaki, O., & Snape, E. (2020). Service leadership, work engagement, and service performance: The moderating role of leader skills. Group & Organization Management, 45(1), 43–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Categories | Employees | Supervisors | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage (%) | Frequency | Percentage (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 320 | 60.40% | 73 | 68.90% |

| Female | 210 | 39.60% | 33 | 31.10% | |

| AGE | Below the age of 30 | 174 | 32.80% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 30–40 | 334 | 63.00% | 52 | 49.10% | |

| Above the age of 40 | 22 | 4.20% | 54 | 50.90% | |

| Education | High school or below | 10 | 1.90% | 0 | 0.00% |

| Junior college degrees | 36 | 6.80% | 0 | 0.00% | |

| Bachelor’s degrees | 470 | 88.70% | 95 | 89.60% | |

| Master’s degrees or above | 14 | 2.60% | 11 | 10.40% | |

| Tenure (in years) | 1–5 | 352 | 66.40% | 3 | 2.80% |

| 5–10 | 173 | 32.60% | 87 | 82.10% | |

| Above 10 | 5 | 1.00% | 16 | 15.10% | |

| Total | 530 | 106 | |||

| Measurement Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five-factor model + CMV | 201.69 | 120 | 1.68 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Five-factor model | 252.76 | 125 | 2.02 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Four-factor model (PE + ER) | 480.38 | 129 | 3.72 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Four-factor model (ESTFL + PE) | 527.20 | 129 | 4.09 | 0.88 | 0.85 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

| Four-factor model (ESTFL + ER) | 609.65 | 129 | 4.73 | 0.85 | 0.82 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Three-factor model (ESTFL + ER + PE) | 767.42 | 132 | 5.81 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Two-factor model (ESTFL + ER + PE + PSVC) | 940.41 | 134 | 7.02 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| One-factor model (ESTFL + ER + PE + PSVC + GVB) | 965.95 | 135 | 7.16 | 0.74 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 0.11 |

| Variables | M | SD | AVE | CR | Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||||

| 1. Gender | 1.40 | 0.49 | - | - | - | ||||||||

| 2. Age | 31.55 | 3.92 | - | - | −0.02 | − | |||||||

| 3. Education | 2.92 | 0.40 | - | - | 0.02 | 0.15 ** | − | ||||||

| 4. Tenure | 3.77 | 1.75 | - | - | −0.07 | 0.71 ** | 0.12 ** | − | |||||

| 5. ESTFL | 3.78 | 0.50 | 0.43 | 0.90 | −0.11 * | −0.01 | 0.11 * | 0.03 | 0.66 | ||||

| 6. PE | 3.74 | 0.52 | 0.41 | 0.89 | −0.03 | −0.09 * | 0.07 | −0.03 | 0.35 ** | 0.64 | |||

| 7. ER | 3.82 | 0.78 | 0.60 | 0.85 | −0.06 | −0.04 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.19 ** | 0.51 ** | 0.77 | ||

| 8. PSVC | 3.76 | 0.86 | 0.68 | 0.86 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.09 * | 0.04 | 0.31 ** | 0.43 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.82 | |

| 9. GVB | 3.78 | 0.87 | 0.67 | 0.86 | −0.05 | 0.01 | 0.13 ** | 0.08 | 0.39 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.61 ** | 0.64 ** | 0.82 |

| Variables | PE | ER | GVB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 2.69 *** | 3.13 *** | −1.26 ** | |||

| Employee gender | 0.01 | −0.06 | 0.03 | |||

| Employee age | −0.02 * | −0.01 | −0.01 | |||

| Employee education | 0.06 | −0.02 | 0.19 ** | |||

| Employee tenure | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 * | |||

| ESTFL | 0.35 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.39 *** | |||

| PE | 0.27 *** | |||||

| ER | 0.55 *** | |||||

| The mediation role of PE/ER on the relationship between ESTFL and GVB | ||||||

| Coeff | LLCI | ULCI | ||||

| Total effect | 0.65 | 0.51 | 0.76 | |||

| Direct effect | 0.39 | 0.28 | 0.51 | |||

| Indirect effect | PE | ER | ||||

| Coeff | LLCI | ULCI | Coeff | LLCI | ULCI | |

| 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.29 | |

| Predictor | PE | ER | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | B | SE | t | p | |

| Moderation model | ||||||||

| Constant | 4.00 *** | 0.22 | 17.99 | <0.001 | 4.19 *** | 0.33 | 12.63 | <0.001 |

| Gender | 0.00 | 0.04 | −0.01 | >0.05 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −1.20 | >0.05 |

| Age | −0.02 * | 0.01 | −2.22 | <0.05 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.85 | >0.05 |

| Education | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.18 | >0.05 | −0.02 | 0.07 | −0.31 | >0.05 |

| Tenure | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.59 | >0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.25 | >0.05 |

| ESTFL | 0.39 *** | 0.05 | 8.06 | <0.001 | 0.36 *** | 0.07 | 4.97 | <0.001 |

| PSVC | 0.25 *** | 0.02 | 10.45 | <0.001 | 0.49 *** | 0.04 | 13.54 | <0.001 |

| ESTFL × PSVC | 0.17 *** | 0.03 | 5.65 | <0.001 | 0.32 *** | 0.04 | 7.21 | <0.001 |

| Moderated mediation model | ||||||||

| PSVC | Indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Indirect effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Index | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.26 |

| Conditional indirect effect at PSVC = M ± 1 SD | ||||||||

| M − 1SD | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.16 |

| M + 1SD | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.51 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, N.; Gao, J.; Chang, P.-C. Can Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership Foster Employees’ Green Voice Behavior? A Moderated Mediation Model of Psychological Empowerment, Ecological Reflexivity, and Value Congruence. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070945

Yang N, Gao J, Chang P-C. Can Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership Foster Employees’ Green Voice Behavior? A Moderated Mediation Model of Psychological Empowerment, Ecological Reflexivity, and Value Congruence. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):945. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070945

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Nianshu, Jialin Gao, and Po-Chien Chang. 2025. "Can Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership Foster Employees’ Green Voice Behavior? A Moderated Mediation Model of Psychological Empowerment, Ecological Reflexivity, and Value Congruence" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070945

APA StyleYang, N., Gao, J., & Chang, P.-C. (2025). Can Environmentally-Specific Transformational Leadership Foster Employees’ Green Voice Behavior? A Moderated Mediation Model of Psychological Empowerment, Ecological Reflexivity, and Value Congruence. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 945. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070945