The Aggressive Gender Backlash in Intimate Partner Relationships: A Theoretical Framework and Initial Measurement

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Aggressive Gender Backlash: Theoretical Proposal

1.2. Research Objectives and Hypotheses

- Establish the psychometric properties of the AGB scale, including its reliability and its dimensional structure.

- Provide evidence of the AGB scale’s discriminant validity by distinguishing it from intimate partner violence against women (IPVAW).

- Assess the scale’s predictive validity by examining the relationship between AGB and key outcomes such as women’s empowerment, subordination, emotional health, and work productivity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.4. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Prevalence, Discrimination, and Item Difficulty

3.2. Reliability and Construct Validity

3.3. Discriminant Validity with IPVAW and Its Dimensions

3.4. Predictive Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications

4.3. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, J., Anderson, C., & Bushman, B. (2018). The general aggression model. Current Opinion in Psychology, 19, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, K., & Zürn, M. (2020). Conceptualizing backlash politics: Introduction to a special issue on backlash politics in comparison. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(4), 563–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2018). Media violence and the general aggression model. Journal of Social Issues, 74, 386–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranov, V., Cameron, L., Contreras Suarez, D., & Thibout, C. (2021). Theoretical underpinnings and meta-analysis of the effects of cash transfers on intimate partner violence in low-and middle-income countries. Journal of Development Studies, 57(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, L. (1993). Aggression: Its causes, consequences, and control. Mcgraw-Hill Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Brescoll, V. L., Okimoto, T. G., & Vial, A. C. (2018). You’ve come a long way…maybe: How moral emotions trigger backlash against women leaders. Journal of Social Issues, 74(1), 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosbe, M. S. (2011). Hostile aggression. In S. Goldstein, & J. A. Naglieri (Eds.), Encyclopedia of child behavior and development. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, K. E., Rudman, L. A., Fetterolf, J. C., Young, D. M., & Chaney, K. E. (2019). Paying a price for domestic equality: Risk factors for backlash against nontraditional husbands. Gender Issues, 36(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, C., Joshi, S., Vecci, J., & Talbot-Jones, J. (2024). Female empowerment and male backlash: Experimental evidence from India. Working Papers in Economics 849. University of Gothenburg, Department of Economics. Available online: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/staff/sjoshi/backlash_india.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Cupać, J., & Ebetürk, I. (2020). The personal is global political: The antifeminist backlash in the United Nations. The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 22(4), 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. P. (1979). Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, K. A., Malone, P. S., Lansford, J. E., Sorbring, E., Skinner, A. T., Tapanya, S., Tirado, L. M., Zelli, A., Alampay, L. P., Al-Hassan, S. M., Bacchini, D., Bombi, A. S., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., Deater-Deckard, K., Di Giunta, L., Oburu, P., & Pastorelli, C. (2015). Hostile attributional bias and aggressive behavior in global context. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(30), 9310–9315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulhunty, A. (2025). A qualitative examination of microfinance and intimate partner violence in India: Understanding the role of male backlash and household bargaining models. World Development, 186, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggers del Campo, I., & Steinert, J. (2022). The effect of female economic empowerment interventions on the risk of intimate partner violence: A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence and Abuse, 23, 810–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericsson-Bergvall, S. (2019). Backlash: Undesirable effects of female economic empowerment. Working Paper 2019:12. Department of Economics, Lund University. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson-Bergvall, S. (2022). Backlash: Female economic empowerment and domestic violence. SSRN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faludi, S. (1991). Backlash: The undeclared war against American women. Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, A. N., Stinson, D. A., & Kalajdzic, A. (2019). Unpacking backlash: Individual and contextual moderators of bias against female professors. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 41(5), 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, M., Dragiewicz, M., & Pease, B. (2021). Resistance and backlash to gender equality. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G. Y., & Zhong, H. (2024). The relationship between gender inequality and female-victim intimate partner homicide in China: Amelioration, backlash or both? Justice Quarterly, 42(2), 336–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, R. K., van der Linden, W. J., & Wells, C. S. (2010). IRT models for the analysis of polytomously scored data: Brief and selected history of model building advances. In M. L. Nering, & R. Ostini (Eds.), Handbook of polytomous item response theory models (pp. 21–42). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Iacoviello, V., Valsecchi, G., Berent, J., Borinca, I., & Falomir-Pichastor, J. M. (2021). The impact of masculinity beliefs and political ideologies on men’s backlash against non-traditional men: The moderating role of perceived Men’s feminization. International Review of Social Psychology, 34(1), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infanger, M., Rudman, L. A., & Sczesny, S. (2016). Sex as a source of power? Backlash against self-sexualizing women. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 19(1), 110–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N. S., & Gottman, J. M. (1998). When men batter women: New insights into ending abusive relationships. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Kilgallen, J., Schaffnit, S., Kumogola, Y., Galura, A., Urassa, M., & Lawson, D. (2022). Positive correlation between women’s status and intimate partner violence suggests violence backlash in Mwanza, Tanzania. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmel, M. S. (2013). Angry white men: American masculinity at the end of an era. Nation Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mansbridge, J., & Shames, S. (2008). Toward a theory of backlash: Dynamic resistance and the central role of power. Politics and Gender, 4(4), 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fernández, M., Gracia, E., & Lila, M. (2019). Psychological intimate partner violence against women in the European Union: A cross-national invariance study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash against modest men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11(2), 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, K. D. (2001). Psychological abuse: A variable deserving critical attention in domestic violence. In K. D. O’Leary, & R. D. Maiuro (Eds.), Psychological abuse in violent domestic relations (pp. 3–28). Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau, L. A. (1979). Power in dating relationships. In J. Freeman (Ed.), Women: A feminist perspective (pp. 260–274). Mayfield Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, J. E., & Rudman, L. A. (2010). Prejudice toward female leaders: Backlash effects and women’s impression management dilemma. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(10), 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pico-Alfonso, M. A., Garcia-Linares, M. I., Celda-Navarro, N., Blasco-Ros, C., Echeburúa, E., & Martinez, M. (2006). The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: Depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. Journal of Women’s Health, 15(5), 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudman, L. A., & Fairchild, K. (2004). Reactions to counterstereotypic behavior: The role of backlash in cultural stereotype maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(2), 157–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Glick, P., & Phelan, J. E. (2012a). Reactions to vanguards. advances in backlash theory. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 167–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Nauts, S. (2012b). Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2008). Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, F., le Masson, V., & Gupta, T. (2019). One step forwards half a step backwards: Changing patterns of intimate partner violence in Bangladesh. Journal of Family Violence, 34(2), 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardinha, L., Maheu-Giroux, M., Stöckl, H., Meyer, S. R., & García-Moreno, C. (2022). Global, regional, and national prevalence estimates of physical or sexual, or both, intimate partner violence against women in 2018. The Lancet, 399(10327), 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, S. R., Lenzi, R., Badal, S. H., & Nazneen, S. (2018). Men’s perspectives on women’s empowerment and intimate partner violence in rural Bangladesh. Culture, Health and Sexuality, 20(1), 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, E. (2007). Coercive control: How men entrap women in personal life. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, E., & Heise, L. (2024). Women’s economic empowerment and intimate partner violence: Untangling the intersections. Evidence brief. Prevention Collaborative. Available online: https://prevention-collaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/5_WEE-Brief-FINALAMENDED.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2024).

- Straus, M. A., Hamby, S. L., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. B. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vara-Horna, A. A. (2024). Violencia y backlash de género contra el empoderamiento de las mujeres en los bancos comunales peruanos. Movimiento Manuela Ramos. Lima. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/381911034_Violencia_y_backlash_de_genero_contra_el_empoderamiento_de_las_mujeres_en_los_bancos_comunales_peruanos (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Vara-Horna, A. A., Asencios-Gonzalez, Z. B., Quipuzco-Chicata, L., & Díaz-Rosillo, A. (2023). Are companies committed to preventing gender violence against women? The role of the manager’s implicit resistance. Social Sciences, 12(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, R. (2021). Learning from practice: Resistance and backlash to preventing violence against women and girls. United Nations Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women. Available online: https://bit.ly/3GVuAXA (accessed on 14 June 2024).

- Wemrell, M. (2022). Stories of Backlash in interviews with survivors of intimate partner violence against women in Sweden. Violence Against Women, 29, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A., Heise, L., Perrin, N., Stuart, C., & Decker, M. R. (2024). Does going against the norm on women’s economic participation increase intimate partner violence risk? A cross-sectional, multi-national study. Global Health Research and Policy, 9(1), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, M. J., & Tiedens, L. Z. (2016). The subtle suspension of backlash: A meta-analysis of penalties for women’s implicit and explicit dominance behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 142(2), 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Aspect | Traditional Psychological Violence | Aggressive Gender Backlash (AGB) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | To cause direct emotional harm, erode self-esteem, and control through fear or explicit humiliation. | Specific resistance to women’s empowerment through indirect actions aimed at reversing or hindering changes in gender power dynamics. |

| Common Manifestations | Insults, explicit threats, humiliation, constant monitoring, direct emotional blackmail, and verbal aggression. | Subtle withdrawal of emotional support, indirect sabotage of personal or work goals, indirect recriminations, and blaming for neglecting traditional gender roles. |

| Explicitness Level | Explicit, easily identifiable as aggression or violence. | More subtle, often mistaken for everyday conflicts or disagreements; less socially recognizable as aggression. |

| Social Consequences | Lower social tolerance, higher likelihood of being reported, and easily recognized by third parties as unacceptable behavior. | Higher social tolerance, perceived as less severe, and rarely reported or recognized as violent behavior. |

| Legal Risk | Higher risk of legal sanctions or judicial interventions due to formal complaints. | Low risk of legal consequences due to difficulty proving or legally recognizing it as aggression. |

| Effects on the Victim | Deep emotional harm, and severe psychological disorders such as anxiety, chronic depression, and evident psychological trauma. | Significant negative emotional impact, progressive deterioration of autonomy and self-esteem specifically related to empowerment, and frustration of personal and professional goals. |

| Role in Relationship | Clear domination, direct emotional control over the partner, and explicit maintenance of power through intimidation. | Indirect maintenance of power through subtle strategies; specific resistance to changes in traditional gender status without necessarily seeking explicit domination through direct fear or intimidation. |

| Processes | Dimensions | Features | How Would Apply to AGB? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal and situational input | Aspects of the situation | Frustration Challenging provocation Social stress Macho socialization Aggressive social models Gender stereotypes Ideal “family” models | Empowered women stop assuming traditional gender roles, increasing men’s frustration. Men socialized with traditional gender roles, with hegemonic masculinity, are more likely to feel frustrated or challenged by their partners’ new roles. |

| Aspects of the individual | Impulsivity Narcissism/Neuroticism Unstable self-esteem Aggressive self-image Male chauvinist attitudes Shifting of responsibility | Men with unstable self-esteem and tolerant attitudes and beliefs towards IPVAW are more prone to AGB. | |

| Internal routes | Physiological activation | Arousal (excitement) | Frustration is felt as intense displeasure, which can increase when hostile feelings or irrational beliefs feed it. |

| Affective states | Hostile feelings Ira Indignation | They are automatic, mainly when men feel socially or personally devalued. Men feel anger at “women’s lack of respect”. | |

| Cognitive states | Irrational beliefs Hostile thoughts Cognitive distortions (attribution biases) | Believing that gender subordination is normal. Blaming the partner for the “insubordination”. Blaming the partner for frustration (false attribution). Believing that the partner is being unfair to him (false justice). | |

| Results | Evaluation and decision process | The cost–benefit evaluation | Cost of the social/legal sanction Benefit of the objective achieved |

| Impulsive action (hostility) | Chronic hostility | (Graduated by intensity.) (1) Annoyance. (2) Torturing silence. (3) Recrimination. (4) Minimization. (5) Aggressive transfer. (6) Aggressive treatment. | |

| Thoughtful action (instrumental) | Gender manipulation | (1) Reduction of social support. (2) Stereotyping. (3) Manipulation. (4) Blame. (5) Sabotage. (6) Repression. | |

| Social gathering | Feedback | Social/legal sanction Subordination achieved Intensity increase |

| Content/Dimension/Description | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Emotional | |

| Hostility: Refers to expressing negative emotions, such as anger, resentment, and contempt, towards the partner. It includes annoyance, scolding, glaring, or belittling the partner’s achievements. It has two levels of intensity (passive–active). | Passive: Has shown annoyance, or bothered you, without telling you the reason. Scolds you for any mistake you make. Blames you for the things you do. Looks at you angrily, as if despising or wanting to hit you. Active: Makes you feel like your goals (work/study) are worthless. Mocks your personal/professional achievements. Mistreats your belongings, as if wanting to destroy them. |

| Behavioral | |

| Withdraw support: Addresses the withdrawal of emotional and social support by the partner, manifested through evasive behaviors. It has one level of intensity. | Treats you coldly, without affection or warmth. Has stopped talking to you, does not look at you, ignores you/acts as if you do not exist for him. Has withdrawn their support as a partner. Does not support you when you ask for it. Refuses to support you with your goals. |

| Sabotage/Coercion: Focuses on instrumental behaviors that seek to hinder or complicate the achievement of the personal and professional goals of the partner. It has two levels of intensity (sabotage and coercion). | Sabotage: Pretends to support you but puts obstacles in your way. Deliberately makes things difficult for you. Complicates your life. Coercion: Does everything possible to make you abandon your goals. Pressures you to quit working/studying. |

| Cognitive | |

| Claims for loss of gender role (stereotyping): Refers to behaviors through which the partner blames the woman for not fulfilling traditional roles of motherhood or wifehood, reflecting internalized gender stereotypes. It has one level of intensity. | Complains that you fulfill your role as a mother or wife. Tells you that you are neglecting your roles as a mother or wife. Tells you that because of your work or studies, you are neglecting the home, the children, or him. Makes you feel bad, that you are not a good mother or wife. Blames you for the problems in the house. Blames you for his infidelities. Says you have disappointed him, that you are not the woman/wife he expected. |

| Claims for affecting his masculinity (playing the victim): Refers to verbal behaviors in which the partner blames the woman for undermining his authority, status, or image as a man. These expressions reflect an attempt to portray himself as a victim and restore perceived masculine dominance. It has one level of intensity. | Says you took away his authority in front of your children. Claims you no longer value him as the head of the household. Accused you of making him look bad in front of his friends/family. Claims you no longer respect him as a man. Says you make him feel less/worthless. |

| Dimensions/Items | Prevalence | Difficulty and Discrimination | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| During the Relationship | Last 12 Months | Diff (1) | Diff (2) | Disc | (Z) | |

| Hostility | 47.1 | 27.6 | ||||

| Shows annoyance or anger without explanation. | 36.5 | 19.2 | 0.505 | 1.152 | 2.161 | 7.73 |

| Scolds or blames you for any mistake. | 32.1 | 18.8 | 0.650 | 1.134 | 2.487 | 7.59 |

| Looks at you with contempt or aggression. | 18.8 | 6.2 | 1.032 | 1.61 | 3.849 | 5.24 |

| Devalues your goals (e.g., work/study) or mocks your achievements. | 12.0 | 5.6 | 1.269 | 1.591 | 4.720 | 5.21 |

| Damages or mistreats your belongings with intent. | 6.8 | 1.2 | 1.540 | 2.150 | 4.118 | 4.55 |

| Withdraw social support | 30.3 | 12.7 | ||||

| Stops talking, avoids eye contact, or acts as if you do not exist. | 22.8 | 9.0 | 0.928 | 1.554 | 2.676 | 7.02 |

| Treats you coldly, without affection or emotional warmth. | 21.6 | 7.4 | 0.976 | 1.622 | 2.937 | 6.82 |

| Refuses support when requested or withdraws it deliberately. | 10.5 | 3.4 | 1.340 | 1.786 | 4.255 | 5.12 |

| Claims damages to masculinity (playing the victim) | 21.8 | 9.5 | ||||

| Says you undermine his authority in front of your children. | 14.8 | 5.5 | 1.343 | 1.925 | 2.369 | 5.92 |

| Claims you no longer value him as head of the household. | 13.9 | 4.0 | 1.310 | 1.962 | 2.865 | 5.85 |

| Claims you no longer respect him as a man. | 10.5 | 2.8 | 1.358 | 1.909 | 3.912 | 5.21 |

| Says you make him look bad in front of his friends/family. | 9.0 | 3.1 | 1.450 | 1.906 | 4.079 | 5.03 |

| Claims you make him feel less/inferior/disrespected. | 8.6 | 1.8 | 1.406 | 1.952 | 4.908 | 4.78 |

| Claims loss of caring role (stereotyping) | 23.8 | 9.3 | ||||

| Criticizes you for neglecting household, children, or him due to work/study. Makes you feel like a bad mother or wife. | 15.5 | 6.2 | 1.307 | 1.894 | 2.255 | 6.03 |

| Demands compliance with traditional gender roles. | 14.2 | 5.6 | 1.355 | 1.924 | 2.342 | 5.91 |

| Blames you for domestic problems or his own infidelities. | 10.2 | 3.4 | 1.412 | 1.919 | 3.25 | 5.42 |

| Expresses disappointment that you are not the woman/wife he expected. | 10.5 | 2.8 | 1.344 | 1.869 | 4.051 | 5.25 |

| Sabotage/Coercion | 20.7 | 7.1 | ||||

| Creates obstacles deliberately or makes your life harder. | 14.5 | 3.4 | 1.224 | 1.914 | 3.326 | 5.92 |

| Pressures you to quit working/studying. | 9.9 | 3.1 | 1.661 | 2.33 | 2.142 | 5.11 |

| Pretends to support you but puts obstacles in your way. | 8.0 | 2.8 | 1.478 | 1.882 | 4.257 | 4.79 |

| Does everything possible to make you abandon your goals. | 7.7 | 1.5 | 1.616 | 2.291 | 2.960 | 4.74 |

| Items | Factor Loadings (Range) | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (Rho C) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second-order construct | |||||

| Aggressive gender backlash | 5 | 0.787–0.909 | 0.924 | 0.933 | 0.678 |

| First-order constructs | |||||

| Claims loss of caring role (stereotyping) | 4 | 0.705–0.845 | 0.776 | 0.857 | 0.601 |

| Claims damages to masculinity (playing the victim) | 5 | 0.678–0.863 | 0.844 | 0.890 | 0.619 |

| Sabotage/Coercion | 4 | 0.699–0.783 | 0.736 | 0.833 | 0.556 |

| Withdraw social support | 3 | 0.795–0.838 | 0.738 | 0.851 | 0.656 |

| Hostility | 5 | 0.644–0.811 | 0.781 | 0.852 | 0.536 |

| IPVAW | AGB | Difference (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever in the relationship | 46.00 | 52.10 | 13.26 |

| In the last 12 months | 11.60 | 31.60 | 172.41 |

| Average incidents (last 12 months) | 27.10 | 41.30 | 52.39 |

| Intimate Partner Violence Against Women | AGB During the Relationship a | AGB During the Last 12 Months b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| No | 92.9% | 35.5% | 97.3% | 70.9% |

| Yes | 7.1% | 64.5% | 2.7% | 29.1% |

| Psychological | Economic | Physical | Sexual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hostility | 0.429 ** | 0.135 ** | 0.151 ** | 0.142 ** |

| Withdraw social support | 0.389 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.112 ** | 0.057 ** |

| Claims loss of caring role (stereotyping) | 0.347 ** | 0.125 ** | 0.100 ** | 0.195 ** |

| Sabotage/Coercion | 0.323 ** | 0.107 ** | 0.093 ** | −0.010 |

| Claims damages to masculinity (playing the victim) | 0.339 ** | 0.145 ** | 0.167 ** | 0.052 ** |

| Fit Indices | Prevalence During the Last 12 Months | Prevalence During the Relationship | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-F | 2-F | 2-F * | 1-F | 2-F | 2-F * | |

| χ2 (df) | 254 (27) | 100.63 (26) | 83.38 (25) | 150.48 (27) | 82.0 (26) | 47.51 (24) |

| CFI | 0.823 | 0.942 | 0.955 | 0.941 | 0.973 | 0.989 |

| TLI | 0.764 | 0.920 | 0.935 | 0.921 | 0.963 | 0.983 |

| NFI | 0.807 | 0.924 | 0.937 | 0.929 | 0.961 | 0.978 |

| GFI | 0.673 | 0.944 | 0.954 | 0.689 | 0.894 | 0.890 |

| RMSEA | 0.131 | 0.076 | 0.069 | 0.096 | 0.066 | 0.045 |

| SRMR | 0.183 | 0.127 | 0.128 | 0.050 | 0.046 | 0.028 |

| Dimensions | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Uniqueness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence during the relationship | |||

| Psychological violence | 0.785 | 0.180 | |

| Economic violence | 0.770 | 0.383 | |

| Physical violence | 0.677 | 0.357 | |

| Sexual violence | 0.594 | 0.712 | |

| Hostility | 0.936 | 0.149 | |

| Withdraw social support | 0.869 | 0.320 | |

| Claims loss of caring role (stereotyping) | 0.666 | 0.498 | |

| Sabotage/Coercion | 0.675 | 0.440 | |

| Claims damages to masculinity (playing the victim) | 0.432 | 0.482 | |

| Prevalence during the last 12 months | |||

| Psychological violence | 0.207 | 0.840 | 0.108 |

| Economic violence | 0.656 | 0.603 | |

| Physical violence | 0.655 | 0.575 | |

| Sexual violence | 0.445 | 0.809 | |

| Hostility | 0.860 | 0.268 | |

| Withdraw social support | 0.754 | 0.432 | |

| Claims loss of caring role (stereotyping) | 0.630 | 0.556 | |

| Sabotage/Coercion | 0.662 | 0.596 | |

| Claims damages to masculinity (playing the victim) | 0.701 | 0.505 |

| AGB | IPVAW | IPVAW (12 Months) | GEP | GSU | EMB | LLP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hostility | 0.520 ** | 0.373 ** | −0.236 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.214 ** | 0.181 ** |

| Withdraw social support | 0.542 ** | 0.353 ** | −0.181 ** | 0.230 ** | 0.118 * | 0.122 * |

| Claims loss of caring role (stereotyping) | 0.426 ** | 0.341 ** | −0.001 | 0.219 ** | 0.067 | 0.078 |

| Sabotage/Coercion | 0.424 ** | 0.260 ** | −0.252 ** | 0.258 ** | 0.099 | 0.141 * |

| Claims damages to masculinity (playing the victim) | 0.491 ** | 0.337 ** | −0.166 ** | 0.338 ** | 0.111 * | 0.130 * |

| AGB (last 12 months prevalence) | 0.583 ** | 0.418 ** | −0.213 ** | 0.345 ** | 0.176 ** | 0.238 ** |

| AGB (relationship prevalence) | 0.690 ** | 0.381 ** | −0.198 ** | 0.291 ** | 0.170 ** | 0.192 ** |

| Hypothesis/Statement | Theoretical Contribution | Implications | Empirical Conclusion/Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1. Not all gender backlash is violent. | Expands GB beyond physical/emotional violence; defines AGB as non-violent but aggressive. | Allows AGB to be measured as an independent variable. | Descriptive evidence: 52.1% of women reported AGB vs. 46% reporting IPVAW. This suggests AGB can occur in the absence of physical violence, though a formal test of difference was not conducted. |

| H2. AGB is different from psychological violence. | Introduces distinct motivational and functional features (resistance vs. harm). | Justify the creation of a specific scale. | Confirmed via discriminant validity: CFA and EFA indicated distinct latent structures between AGB and psychological violence. |

| H3. AGB is a precursor and risk factor for IPVAW. | AGB may precede or escalate into IPVAW under certain conditions. | AGB should be targeted in early prevention efforts. | Correlational evidence: 64.5% of those experiencing AGB also reported IPVAW; only 7.1% reported IPVAW without AGB. While suggestive, no longitudinal or predictive model was tested. |

| H4. AGB is more prevalent than IPVAW. | Highlights the normalized and underestimated presence of AGB. | AGB must be addressed in public policy. | Descriptive evidence: 172% higher prevalence of AGB than IPVAW in the last 12 months. No inferential test of proportion difference was conducted. |

| H5. AGB has a graduated behavioral intensity spectrum. | Frames AGB behaviors along an intensity continuum. | Facilitates the construction of graded scales and risk profiles. | Supported by IRT analysis: Items showed graded difficulty and prevalence levels; lower-intensity items were more frequent than high-intensity ones. |

| H6. AGB is a second-order latent variable. | Positions AGB as a multidimensional construct. | Justifies the use of SEM and scales with multiple dimensions. | Confirmed: SEM-PLS analysis demonstrated adequate model fit for five dimensions with good convergent validity. |

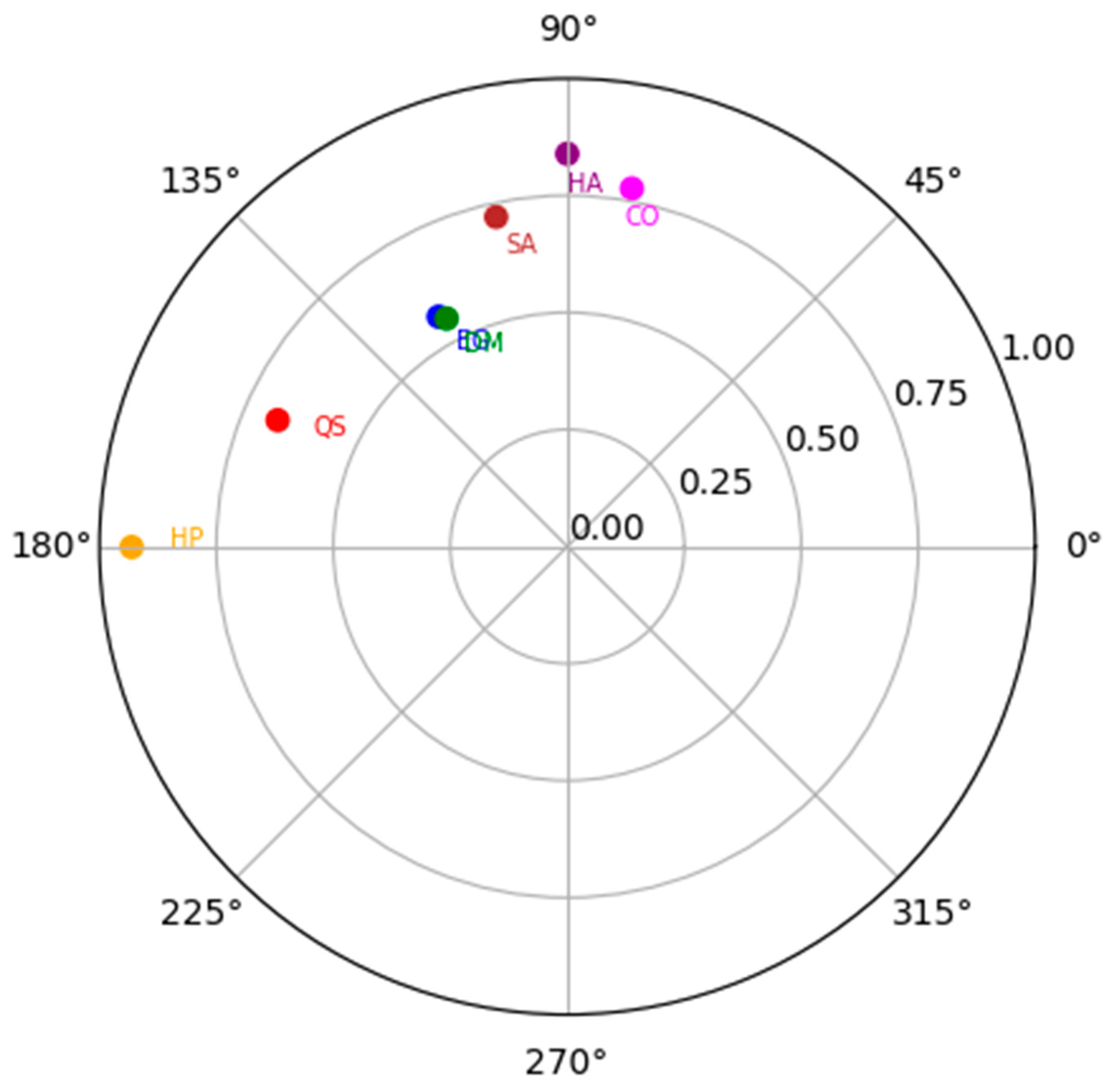

| H7. AGB has a semi-circumplex structure. | Suggests spatial and functional interrelation between AGB dimensions. | Supports visual models for training and intervention. | Supported: Polar coordinate analysis and factor rotation showed a structured two-dimensional pattern; CFI = 0.991. |

| H8. AGB is as effective as IPVAW in subordinating women and limiting their empowerment, and as harmful due to its chronic nature. | Proposes functional and affective equivalence between AGB and IPVAW. Challenges the assumption that only violence produces serious harm. | Interventions and public policy should treat AGB as a high-priority mechanism of subordination. | Correlational evidence: AGB is associated with lower empowerment, emotional distress, and lower productivity. Causality or equivalence not formally tested. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vara-Horna, A.A.; Rodríguez-Espartal, N. The Aggressive Gender Backlash in Intimate Partner Relationships: A Theoretical Framework and Initial Measurement. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070941

Vara-Horna AA, Rodríguez-Espartal N. The Aggressive Gender Backlash in Intimate Partner Relationships: A Theoretical Framework and Initial Measurement. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):941. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070941

Chicago/Turabian StyleVara-Horna, Aristides A., and Noelia Rodríguez-Espartal. 2025. "The Aggressive Gender Backlash in Intimate Partner Relationships: A Theoretical Framework and Initial Measurement" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070941

APA StyleVara-Horna, A. A., & Rodríguez-Espartal, N. (2025). The Aggressive Gender Backlash in Intimate Partner Relationships: A Theoretical Framework and Initial Measurement. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 941. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070941