META—Measurement for Evolution, Transformation, and Autorealization: A New Assessment Protocol

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Concept of Self-Realization

1.2. Theoretical Background

1.2.1. Self-Realization Within the Positive Psychology Framework

1.2.2. Self-Realization in the Organizational Context

1.3. The Present Research

- To develop the items of the META and assess its psychometric properties. This involved item generation, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, and internal consistency and reliability evaluation;

- To examine the relationship between META scores and outcomes (work-related and non-work-related) typically associated with some self-realization. This included measures of life satisfaction, career adaptability, general self-efficacy, insight orientation, and resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants, Procedure, and Ethics

2.2. Development of the Measurement for Evolution, Transformation, and Autorealization (META)

- Being jargon-free and avoiding colloquialisms, to adapt to different cultural contexts and educational levels;

- Being of easy use (i.e., being agile both in the administration and in the scoring);

- Being useful in different phases of personal and work orientation and maintaining an interdisciplinary scope (work orientation, psychological treatment, psychotherapy, etc.).

- -

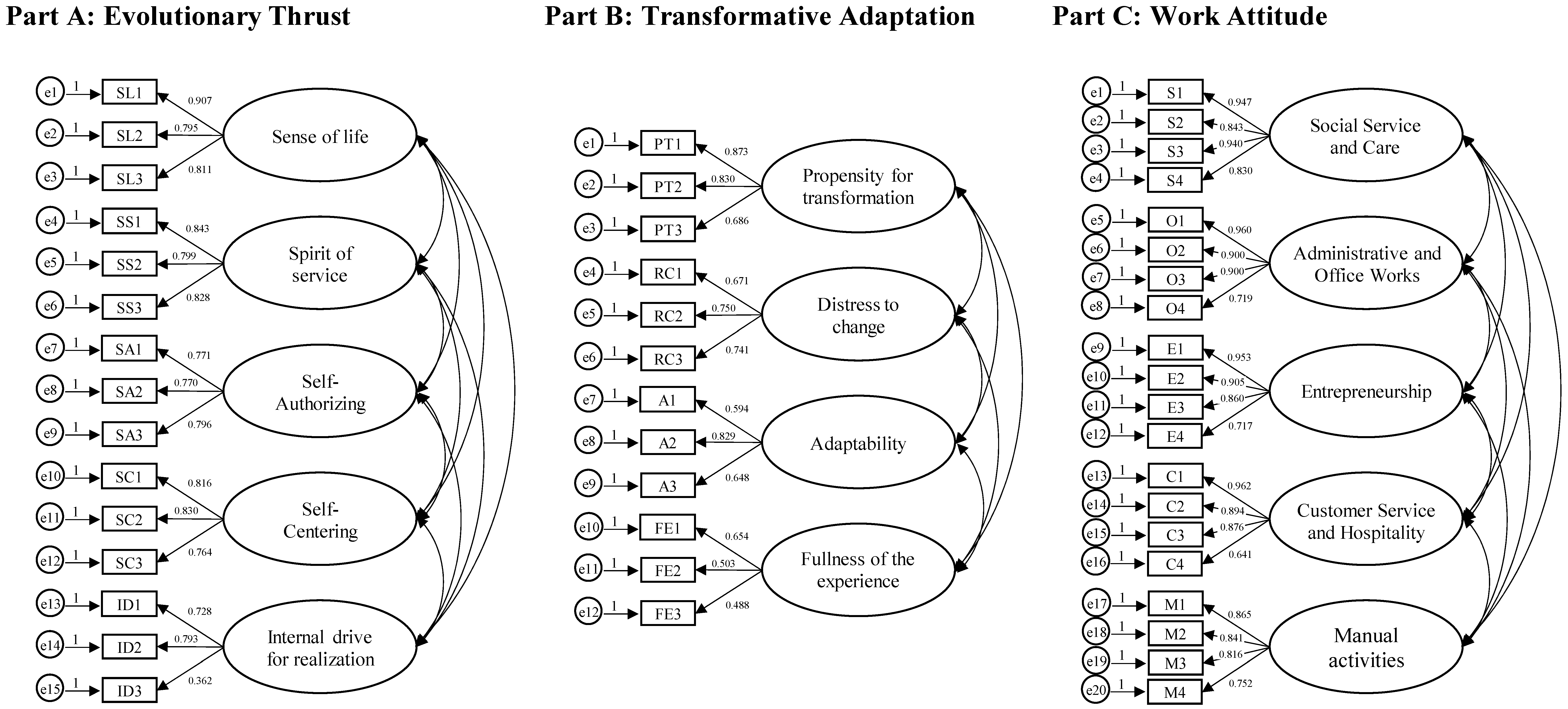

- Evolutionary Thrust (Part A) concerns the intrinsic evolutionary drive that guides individuals or systems towards realizing their potential and fostering progress in themselves and others (Banathy, 1987). The focus of this part was on the abstract, internal, and profound dynamics that can influence the propensity for self-realization. Specifically, five subdimensions were included:

- Sense of life, i.e., the perception and awareness of one’s life’s purpose, meaning, and direction. This concept encompasses the subjective experience of one’s life as coherent and significant, and is often associated with notions of fulfilment and personal significance (Wong, 2015; Steger et al., 2021). Research consistently demonstrates a strong connection between a sense of life and enhanced well-being. Indeed, having a strong sense of life is positively correlated with happiness and negatively related to anxiety and depression (Crego et al., 2021). Additionally, previous evidence suggests that purpose in life may lead to better physical health outcomes, such as reduced risk of chronic diseases and improved longevity (Martela et al., 2024; Musich et al., 2018).

- Spirit of service, i.e., a deeply ingrained motivation to support others, which is often driven by altruistic values. This concept involves the desire to dedicate oneself to the well-being of others (Loizzo et al., 2012). Altruism and helping behaviors can also be a source of personal growth and well-being (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Indeed, previous research has shown significant and positive correlations between prosociality and emotional, relational, and life satisfaction (Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999; C. Lu et al., 2021; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010).

- Self-Authorizing, i.e., the sense of personal authorization in making independent decisions and choices, granting themselves the authority to determine their actions and paths in life. This concept is critical in fostering a sense of control and agency (Oshana, 2014). Autonomy, a core component of self-authorizing, supports the development of self-respect and personal fulfilment, which are critical for emotional and psychological health (Johnston, 2021). Consistently, previous research showed that fostering a sense of self-authority and personal autonomy may contribute to emotional stability and life satisfaction (O’Hara & Lyon, 2014).

- Self-Centering, i.e., a state of alignment where individuals are deeply connected with their passions, interests, and personal identity through their activities. This connection creates a state of harmony and resonance between an individual’s inner self and their external actions (Franklin, 2022). Previous research has explored the importance of this factor in the workplace. For example, existing evidence shows that the alignment between personal and professional identity is associated with greater job satisfaction (Zhang et al., 2018), lower risk of burnout (Rasmussen et al., 2018), and better job outcomes (Fitzgerald, 2020).

- Internal drive for realization, i.e., the intrinsic motivation to achieve personal fulfilment, seek a life purpose, and evolve. This drive supports personal development and growth, as it propels individuals towards continuous self-improvement and the attainment of meaningful goals (Weinstein et al., 2013). The internal drive for realization encourages individuals to continuously develop their skills, knowledge, and abilities (Bedan et al., 2021; Palamarchuk & Haba, 2023). This process of personal development is essential for achieving long-term goals and improving overall well-being (Maksimenko & Serdiuk, 2016; Waterman et al., 2003)

- -

- Transformative Adaptation (Part B) concerns the ability to create new pathways to facilitate development, growth, and evolution (see Ajulo et al., 2020 for a review). The focus of this part was on experiential, external and behavioral dynamics, which are practically useful for self-realization. Specifically, four subdimensions were included:

- Propensity for transformation, i.e., an inclination to actively seek, welcome, and engage in significant life changes aimed at personal growth and development. Individuals with a high propensity for transformation are often characterized by their proactive approach to life changes: they are not only open to new experiences but actively seek them out, driven by a desire for self-improvement (Di Fabio & Gori, 2016a). Research consistently shows that individuals with a high propensity for transformation are more likely to turn adversity into opportunities for personal development, exhibiting greater posttraumatic growth (Lepore & Revenson, 2014). Consistently, longitudinal studies have highlighted that openness to experience, which correlates with a propensity for transformation, can lead to significant personality development and positive changes over time (Caspi & Roberts, 2001).

- Distress to change (the only reverse subdimension), i.e., the tendency to resist or struggle with changes in life, a general reluctance to embrace change. This aversion can manifest in various ways, including emotional discomfort, behavioral rigidity, and cognitive inflexibility (Ridner, 2004). Individuals with high levels of distress in response to changes often experience increased levels of burnout and emotional illness (Sablonnière et al., 2012). The inability to adapt to new situations can lead to a sense of helplessness and decreased psychological well-being (Oreg, 2003).

- Adaptability, i.e., the ability to adjust to new conditions, alter one’s path when necessary, and change habits in response to changing circumstances. This construct reflects a person’s flexibility, problem-solving skills, and resilience (Coşkun et al., 2014; Nakhostin-Khayyat et al., 2024). The ability to adjust to new and challenging situations can help to effectively manage emotional distress (Bocciardi et al., 2017), fostering hope, optimism, and life satisfaction (Santilli et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2013). Furthermore, it can enhance tolerance of uncertainty, directing efforts to understand uncertain situations into creative thoughts and actions (Beghetto, 2019; Orkibi, 2021).

- Fullness of the experience, i.e., the propensity to capture the richness and depth of an individual’s engagement with life. This concept highlights a motivation to learn and gain insights from lived experiences (Csikszentmihalhi, 2020). This mindset may lead to ongoing self-improvement and the acquisition of new skills and perspectives, favoring personal growth (Hood & Carruthers, 2007). Indeed, by engaging deeply with their experiences, individuals cultivate new skills and broaden their perspectives. This approach not only enhances their problem-solving abilities but also enriches their overall life satisfaction and well-being (Csikszentmihalhi, 2020).

- -

- Work Attitude (Part C) is related to work orientation with respect to different types of activities and sectors. Specifically, five subdimensions were included:

- Social Service and Care, i.e., jobs in helping professions and social settings. Examples include working in nursing homes, providing support services, social work, nursing, working with individuals in need of assistance, community work, teaching, and childcare.

- Administrative and Office Works, i.e., occupations in which tasks commonly associated with office environments are performed. Examples include administration, accounting, computer proficiency, working with numbers, and experience in banking, public services, technology, and advertising.

- Entrepreneurship, i.e., self-directed work and professions that involve starting or managing businesses. Examples include freelancers, engineers, architects, lawyers, doctors, psychologists, sports professionals, traders, and retail business owners (clothing/jewelry shops).

- Customer Service and Hospitality, i.e., jobs requiring effective interaction with customers in tourism, including service-oriented roles. Examples include work in hotels, restaurants, bars, nightclubs, bed and breakfasts, souvenir shops, street vending, and tour guides.

- Manual activities, i.e., occupations in which hands-on tasks, including those involved in construction, manufacturing, transportation, and maintenance, are performed. Examples include laborers, industrial workers, drivers, farmers, painters, sculptors, carpenters, bricklayers, cleaning service personnel, electricians, and plumbers.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Measurement for Evolution, Transformation, and Autorealization (META)

2.3.2. Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS)

2.3.3. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (CAAS)

2.3.4. General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES)

2.3.5. Insight Orientation Scale (IOS)

2.3.6. 10-Item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (I-CD-RISC-10)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

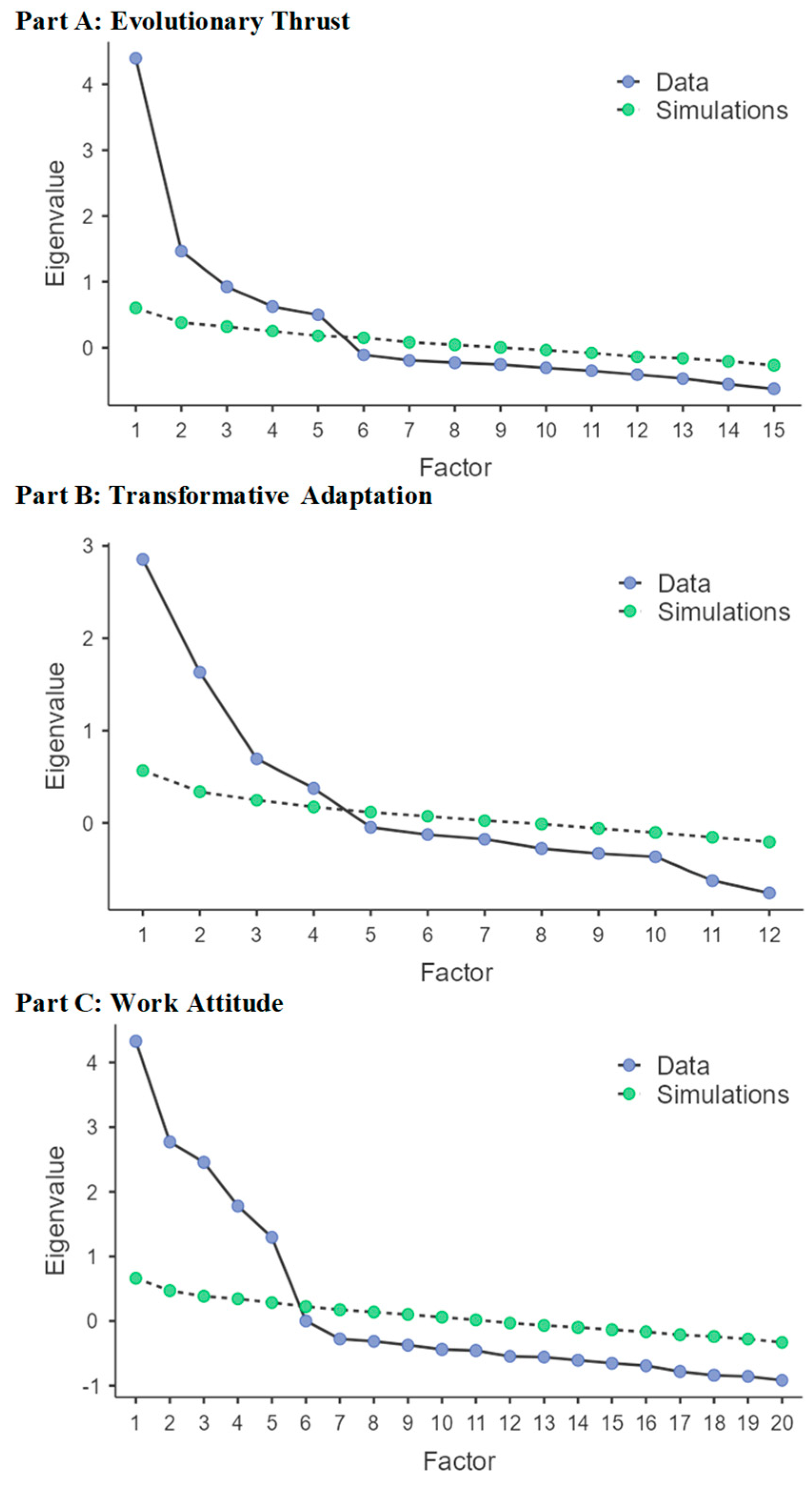

3.2. Factor Analysis and Internal Consistency

3.3. Convergent and Discriminant Validity

4. Discussion

4.1. META: Development and Exploration of the Psychometric Properties

4.2. Association Between the META and Self-Realization or Well-Being Outcomes

4.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

4.4. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ajulo, O., Von-Meding, J., & Tang, P. (2020). Upending the status quo through transformative adaptation: A systematic literature review. Progress in Disaster Science, 6, 100103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D. G., Bryant, P. C., & Vardaman, J. M. (2010). Retaining talent: Replacing misconceptions with evidence-based strategies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(2), 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atitsogbe, K. A., Mama, N. P., Sovet, L., Pari, P., & Rossier, J. (2019). Perceived employability and entrepreneurial intentions across university students and job seekers in Togo: The effect of career adaptability and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banathy, B. H. (1987). The characteristics and acquisition of evolutionary competence. World Futures: Journal of General Evolution, 23(1–2), 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedan, V., Brynza, I., Budiianskyi, M., Vasylenko, I., Vodolazska, O., & Ulianova, T. (2021). Motivative factors of professional self-realization of the person. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience, 12(2), 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A. (2019). Structured uncertainty: How creativity thrives under constraints and uncertainty. In C. A. Mullen (Ed.), Creativity under duress in education? Resistive theories, practices, and actions (pp. 27–40). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bialowolski, P., & Weziak-Bialowolska, D. (2021). Longitudinal evidence for reciprocal effects between life satisfaction and job satisfaction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(3), 1287–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocciardi, F., Caputo, A., Fregonese, C., Langher, V., & Sartori, R. (2017). Career adaptability as a strategic competence for career development: An exploratory study of its key predictors. European Journal of Training and Development, 41(1), 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, B. P., & Schaufeli, W. B. (1999). Reciprocity in interpersonal relationships: An evolutionary perspective on its importance for health and well-being. European Review of Social Psychology, 10(1), 259–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., Gelbard, R., & Gefen, D. (2010). The importance of innovation leadership in cultivating strategic fit and enhancing firm performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 21(3), 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S. (1998). Resilience and thriving: Issues, models, and linkages. Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspi, A., & Roberts, B. W. (2001). Personality development across the life course: The argument for change and continuity. Psychological Inquiry, 12(2), 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y., Kim, M., & Choi, M. (2021). Factors associated with nurses’ user resistance to change of electronic health record systems. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coşkun, Y. D., Garipağaoğlu, Ç., & Tosun, Ü. (2014). Analysis of the relationship between the resiliency level and problem solving skills of university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crego, A., Yela, J. R., Gómez-Martínez, M. Á., Riesco-Matías, P., & Petisco-Rodríguez, C. (2021). Relationships between mindfulness, purpose in life, happiness, anxiety, and depression: Testing a mediation model in a sample of women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(2), 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csikszentmihalhi, M. (2020). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Hachette UK. [Google Scholar]

- Debreceni, J., & Fekete-Frojimovics, Z. (2023). Understanding resilience in tourism and hospitality. Regional and Business Studies, 15(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2018a). Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018b). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Fabio, A. (2017). Positive healthy organizations: Promoting well-being, meaningfulness, and sustainability in organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 300313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2016a). Developing a new instrument for assessing acceptance of change. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 197329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2016b). Measuring adolescent life satisfaction: Psychometric properties of the satisfaction with life scale in a sample of Italian adolescents and young adults. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(5), 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2020). Satisfaction with life scale among Italian workers: Reliability, factor structure and validity through a big sample study. Sustainability, 12(14), 5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A., & Palazzeschi, L. (2012). Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale: Proprietà psicometriche della versione italiana [Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale: Psychometric properties of the Italian version]. Counseling, 5, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Di Fabio, A., Giannini, M., Loscalzo, Y., Palazzeschi, L., Bucci, O., Guazzini, A., & Gori, A. (2016). The challenge of fostering healthy organizations: An empirical study on the role of workplace relational civility in acceptance of change and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 212165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2009). Calling and vocation at work: Definitions and prospects for research and practice. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(3), 424–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Eldridge, B. M. (2009). Calling and vocation in career counseling: Recommendations for promoting meaningful work. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(6), 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dik, B. J., Eldridge, B. M., Steger, M. F., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Development and validation of the Calling and Vocation Questionnaire (CVQ) and Brief Calling Scale (BCS). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 242–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrow, S. R., & Tosti-Kharas, J. (2011). Calling: The development of a scale measure. Personnel Psychology, 64, 1001–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. D., & Dik, B. J. (2013). Research on calling: What have we learned and where are we going? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 428–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. D., Autin, K. L., Allan, B. A., & Douglass, R. P. (2015). Assessing work as a calling: An evaluation of instruments and practice recommendations. Journal of Career Assessment, 23(3), 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, R. D., Dik, B. J., Douglass, R. P., England, J. W., & Velez, B. L. (2018). Work as a calling: A theoretical model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(4), 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, R. D., Perez, G., Dik, B. J., & Marsh, D. R. (2023). Work as calling theory. In W. B. Walsh, L. Y. Flores, P. J. Hartung, & F. T. L. Leong (Eds.), Career psychology: Models, concepts, and counseling for meaningful employment (pp. 101–119). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteves, T., & Lopes, M. P. (2017). Crafting a calling: The mediating role of calling between challenging job demands and turnover intention. Journal of Career Development, 44(1), 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, A. (2020). Professional identity: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 55(3), 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1986). Stress processes and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(2), 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankl, V. E. (1963). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. Washington Square Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, E. (2022). Dynamic alignment through imagery. Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, C. M., & Lazzara, E. H. (2020). Examining gender and enjoyment: Do they predict job satisfaction and well-being? The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 23(3–4), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, J., & James, M. (2019). HTMT plugin for AMOS. Available online: http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com/index.php?title=Plugins (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Gielnik, M. M., Bledow, R., & Stark, M. S. (2020). A dynamic account of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 487–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, A., & Topino, E. (2020). Predisposition to change is linked to job satisfaction: Assessing the mediation roles of workplace relation civility and insight. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(6), 2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A., Craparo, G., Giannini, M., Loscalzo, Y., Caretti, V., La Barbera, D., & Schuldberg, D. (2015). Development of a new measure for assessing insight: Psychometric properties of the insight orientation scale (IOS). Schizophrenia Research, 169(1–3), 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gori, A., Svicher, A., Palazzeschi, L., & Di Fabio, A. (2022a). Acceptance of Change Among Workers for Sustainability in Organizations: Trait Emotional Intelligence and Insight Orientation. In Cross-cultural perspectives on well-being and sustainability in organizations (pp. 203–211). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gori, A., Topino, E., Brugnera, A., & Compare, A. (2022b). Assessment of professional self-efficacy in psychological interventions and psychotherapy sessions: Development of the Therapist Self-Efficacy Scale (T-SES) and its application for eTherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78, 2122–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A., Topino, E., Cacioppo, M., Schimmenti, A., & Caretti, V. (2023). Definition and criteria for the assessment of expertise in psychotherapy: Development of the Psychotherapy Expertise Questionnaire (PEQ). European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 13(11), 2478–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A., Topino, E., Svicher, A., & Di Fabio, A. (2022c). Towards meaning in life: A path analysis exploring the mediation of career adaptability in the associations of self-esteem with presence of meaning and search for meaning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 11901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gori, A., Topino, E., Svicher, A., Schuldberg, D., & Di Fabio, A. (2022d). Insight orientation scale: A promising tool for organizational outcomes—A psychometric analysis using item response theory. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 987931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, L. M., Ruderman, M. N., Ohlott, P. J., & Weber, T. J. (2012). Driven to work and enjoyment of work: Effects on managers’ outcomes. Journal of Management, 38(5), 1655–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzeller, C. O., & Celiker, N. (2020). Examining the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention via a meta-analysis. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1), 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagmaier, T., & Abele, A. E. (2012). The multidimensionality of calling: Conceptualization, measurement and a bicultural perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81(1), 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P. L., Brannan, J. D., & De Chesnay, M. (2014). Resilience in nurses: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(6), 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., Keller, A. C., & Spurk, D. M. (2018). Living one’s calling: Job resources as a link between having and living a calling. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 106, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjelle, M. (2024). The reflective entrepreneur: Tools that increase metacognition during venture creation programs. In Stimulating entrepreneurial activity in a european context (pp. 70–89). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, C. D., & Carruthers, C. P. (2007). Enhancing leisure experience and developing resources: The leisure and well-being model part II. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 41(4), 298–325. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huta, V., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Pursuing pleasure or virtue: The differential and overlapping well-being benefits of hedonic and eudaimonic motives. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(6), 735–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R. (2021). Autonomy, Relational Egalitarianism, and Indignation. In Autonomy and equality (pp. 125–144). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A., & Crandall, R. (1986). Validation of a short index of self-actualization. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12(1), 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, B. K., Jeung, C. W., & Yoon, H. J. (2010). Investigating the influences of core self-evaluations, job autonomy, and intrinsic motivation on in-role job performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(4), 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2006). Growth following adversity: Theoretical perspectives and implications for clinical practice. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(8), 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, T. A., Thoresen, C. J., Bono, J. E., & Patton, G. K. (2001). The job satisfaction–job performance relationship: A qualitative and quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin, 127(3), 376–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H., & Kaur, R. (2020). The relationship between career adaptability and job outcomes via fit perceptions: A three-wave longitudinal study. Australian Journal of Career Development, 29(3), 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegan, R. (1994). In over our heads: The mental demands of modern life. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. S., Pak, J., & Son, S. Y. (2023). Do calling-oriented employees take charge in organizations? The role of supervisor close monitoring, intrinsic motivation, and organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 140, 103812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Korber, S., & McNaughton, R. B. (2017). Resilience and entrepreneurship: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 24(7), 1129–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepore, S. J., & Revenson, T. A. (2014). Resilience and posttraumatic growth: Recovery, resistance, and reconfiguration. In L. G. Calhoun, & R. G. Tedeschi (Eds.), Handbook of posttraumatic growth: Research and practice (pp. 24–46). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, N. A., & Hill, P. L. (2021). Sense of purpose promotes resilience to cognitive deficits attributable to depressive symptoms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 698109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Wood, A. M., Osborne, G., & Hurling, R. (2009). Measuring happiness: The higher order factor structure of subjective and psychological well-being measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wang, Z., & Lü, W. (2013). Resilience and affect balance as mediators between trait emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(7), 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loizzo, J., Thurman, R. A., & Siegel, D. J. (2012). Sustainable happiness: The mind science of well-being, altruism, and inspiration. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C., Liang, L., Chen, W., & Bian, Y. (2021). A way to improve adolescents’ life satisfaction: School altruistic group games. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 533603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M., Zou, Y., Chen, X., Chen, J., He, W., & Pang, F. (2020). Knowledge, attitude and professional self-efficacy of Chinese mainstream primary school teachers regarding children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 72, 101513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F., Youssef-Morgan, C. M., & Avolio, B. J. (2015). Psychological capital and beyond. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maksimenko, S., & Serdiuk, L. (2016). Psychological potential of personal self-realization. Social Welfare: Interdisciplinary Approach, 6(1), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1985). Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First- and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychological Bulletin, 97(3), 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F., & Pessi, A. B. (2018). Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 307096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F., Laitinen, E., & Hakulinen, C. (2024). Which predicts longevity better: Satisfaction with life or purpose in life? Psychology and Aging. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R. P. (2013). Test theory: A unified treatment. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miao, M., & Cao, R. (2024). Mutually beneficial relationship between meaning in life and resilience. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 58, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaik, S. A. (2009). Foundations of factor analysis. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Murtagh, N., Gatersleben, B., & Uzzell, D. (2012). Self-identity threat and resistance to change: Evidence from regular travel behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32(4), 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musich, S., Wang, S. S., Kraemer, S., Hawkins, K., & Wicker, E. (2018). Purpose in life and positive health outcomes among older adults. Population Health Management, 21(2), 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhostin-Khayyat, M., Borjali, M., Zeinali, M., Fardi, D., & Montazeri, A. (2024). The relationship between self-regulation, cognitive flexibility, and resilience among students: A structural equation modeling. BMC Psychology, 12, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R. G., Bearden, W. O., & Sharma, S. (2003). Scaling procedures: Issues and applications. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A., Obschonka, M., Schwarz, S., Cohen, M., & Nielsen, I. (2019). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, M., & Lyon, A. (2014). Well-being and well-becoming: Reauthorizing the subject in incoherent times. In Well-being and beyond (pp. 98–122). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Oreg, S. (2003). Resistance to change: Developing an individual differences measure. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(4), 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oreg, S., & Goldenberg, J. (2015). Resistance to innovation: Its sources and manifestations. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Orkibi, H. (2021). Creative adaptability: Conceptual framework, measurement, and outcomes in times of crisis. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 588172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshana, M. (2014). Trust and autonomous agency. Res Philosophica, 91(3), 431–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamarchuk, O., & Haba, I. (2023). The impact of uncertain conditions on the self-realization of modern individuals. Personality and Environmental Issues, 6, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paloş, R., Vîrgă, D., & Craşovan, M. (2022). Resistance to change as a mediator between conscientiousness and teachers’ job satisfaction. The moderating role of learning goals orientation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 757681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, N., Park, M., & Peterson, C. (2010). When is the search for meaning related to life satisfaction? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 2(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praskova, A., Creed, P. A., & Hood, M. (2015). The development and initial validation of a career calling scale for emerging adults. Journal of Career Assessment, 23(1), 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, P., Henderson, A., Andrew, N., & Conroy, T. (2018). Factors influencing registered nurses’ perceptions of their professional identity: An integrative literature review. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 49(5), 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridner, S. H. (2004). Psychological distress: Concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(5), 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, C. R. (1995). On becoming a person: A therapist’s view of psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., Huta, V., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Living well: A self-determination theory perspective on eudaimonia. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (2013). Eudaimonic well-being and health: Mapping consequences of self-realization. In A. S. Waterman (Ed.), The best within us: Positive psychology perspectives on eudaimonia (pp. 77–98). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sablonnière, R. D. L., Tougas, F., Sablonnière, É. D. L., & Debrosse, R. (2012). Profound organizational change, psychological distress and burnout symptoms: The mediator role of collective relative deprivation. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 15(6), 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, S., Marcionetti, J., Rochat, S., Rossier, J., & Nota, L. (2017). Career adaptability, hope, optimism, and life satisfaction in Italian and Swiss adolescents. Journal of Career Development, 44(1), 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. The Career Development Quarterly, 45(3), 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, R. J., Hicks, J. A., King, L. A., & Arndt, J. (2011). Feeling like you know who you are: Perceived true self-knowledge and meaning in life. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(6), 745–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schueller, S. M., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2010). Pursuit of pleasure, engagement, and meaning: Relationships to subjective and objective measures of well-being. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(4), 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, D. J. (2004). Vocation: Discerning our callings in life. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized Self-Efficacy Scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). NFER-NELSON. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In M. Csikszentmihalyi (Ed.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 279–298). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M. (2011). Integrating behavioral-motive and experiential-requirement perspectives on psychological needs: A two process model. Psychological Review, 118(4), 552–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M., Wang, X., Bian, Y., & Wang, L. (2015). The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between stress and life satisfaction among Chinese medical students: A cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Education, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sibilia, L., Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Italian adaptation of the General Self-Efficacy Scale: Self-Efficacy Generalized. Available online: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/health/italian.htm (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Soresi, S., Nota, L., & Ferrari, L. (2012). Career adapt-abilities scale-Italian form: Psychometric properties and relationships to breadth of interests, quality of life, and perceived barriers. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F. (2012). Making meaning in life. Psychological Inquiry, 23(4), 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. F., O’Donnell, M. B., & Morse, J. L. (2021). Helping students find their way to meaning: Meaning and purpose in education. In M. L. Kern, & M. L. Wehmeyer (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of positive education (pp. 551–579). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Steger, M. F., Pickering, N. K., Shin, J. Y., & Dik, B. J. (2010). Calling in work: Secular or sacred? Journal of Career Assessment, 18(1), 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D. E. (1980). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 16(3), 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super, D. E., & Knasel, E. G. (1981). Career development in adulthood: Some theoretical problems and a possible solution. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 9(2), 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The jamovi project. (2024). jamovi, (Version 2.5) [Computer Software]; Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 9 June 2024).

- Topino, E., Svicher, A., Di Fabio, A., & Gori, A. (2022). Satisfaction with life in workers: A chained mediation model investigating the roles of resilience, career adaptability, self-efficacy, and years of education. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1011093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugade, M. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Resilient individuals use positive emotions to bounce back from negative emotional experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86(2), 320–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turgut, S., Michel, A., Rothenhöfer, L. M., & Sonntag, K. (2016). Dispositional resistance to change and emotional exhaustion: Moderating effects at the work-unit level. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(5), 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, M., Salanova, M., & Llorens, S. (2015). Professional self-efficacy as a predictor of burnout and engagement: The role of challenge and hindrance demands. The Journal of Psychology, 149(3), 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, M., Dalla Rosa, A., Anselmi, P., & Galliani, E. M. (2018). Validity and measurement invariance of the Unified Multidimensional Calling Scale (UMCS): A three-wave survey study. PLoS ONE, 13(12), e0209348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, M. A., & Bridwell, L. G. (1976). Maslow reconsidered: A review of research on the need hierarchy theory. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 15(2), 212–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Goldbacher, E., Green, H., Miller, C., & Philip, S. (2003). Predicting the subjective experience of intrinsic motivation: The roles of self-determination, the balance of challenges and skills, and self-realization values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(11), 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: Autonomous motivation for prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(2), 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2013). Motivation, meaning, and wellness: A self-determination perspective on the creation and internalization of personal meanings and life goals. In P. T. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (pp. 81–106). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram, H. J. (2023). Meaning in life, life role importance, life strain, and life satisfaction. Current Psychology, 42(34), 29905–29917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2011). Positive psychology 2.0: Toward a balanced interactive model of the good life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 52(2), 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning: Theories, research, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 3–22). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2015). Meaning therapy: Assessments and interventions. Existential Analysis, 26(1), 154–167. [Google Scholar]

- Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A., Pandita, D., & Singh, S. (2022). Work-life integration, job contentment, employee engagement and its impact on organizational effectiveness: A systematic literature review. Industrial and Commercial Training, 54(3), 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Meng, H., Yang, S., & Liu, D. (2018). The influence of professional identity, job satisfaction, and work engagement on turnover intention among township health inspectors in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(5), 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żołnierczyk-Zreda, D. (Ed.). (2020). Healthy worker and healthy organization: A resource-based approach. CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | M ± SD | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.32 ± 14.965 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Males | 172 (27.1%) | ||

| Females | 462 (72.9%) | ||

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 342 (53.9%) | ||

| Married | 170 (26.8%) | ||

| Cohabiting | 76 (12.0%) | ||

| Separated | 15 (2.4%) | ||

| Divorced | 22 (3.5%) | ||

| Widowed | 9 (1.4%) | ||

| Education | |||

| Elementary School diploma | 2 (0.3%) | ||

| Middle School diploma | 45 (7.1%) | ||

| High School diploma | 257 (40.5%) | ||

| University degree | 138 (21.8%) | ||

| Master’s degree | 134 (21.1%) | ||

| Post-lauream specialization | 58 (9.1%) | ||

| Occupation | |||

| Student | 150 (23.7%) | ||

| Working student | 65 (10.3%) | ||

| Artisan | 12 (1.9%) | ||

| Employee | 241 (38.0%) | ||

| Entrepreneur | 22 (3.5%) | ||

| Freelance | 40 (6.3%) | ||

| Retired | 31 (4.9%) | ||

| Trader | 8 (1.3%) | ||

| Religious | 3 (0.5%) | ||

| Manager | 12 (1.9%) | ||

| Unemployed | 50 (7.9%) | ||

| Section | Factors | Items (N) | α | ω | Inter-Factor Correlations (Above the Diagonal) and HTMT Analysis (Below the Diagonal). | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

| Part A | N = 5 | 15 | 0.806 | 0.828 | |||||

| Evolutionary Thrust | 1. Sense of life | 3 | 0.884 | 0.886 | — | 0.455 | 0.491 | 0.540 | 0.033 |

| 2. Spirit of service | 3 | 0.861 | 0.862 | 0.370 | — | 0.298 | 0.236 | 0.270 | |

| 3. Self-Authorizing | 3 | 0.845 | 0.846 | 0.483 | 0.189 | — | 0.513 | 0.098 | |

| 4. Self-Centering | 3 | 0.837 | 0.840 | 0.551 | 0.225 | 0.505 | — | −0.010 | |

| 5. Internal drive for realization | 3 | 0.657 | 0.694 | 0.096 | 0.224 | 0.028 | 0.009 | — | |

| Part B | N = 4 | 12 | 0.721 | 0.754 | |||||

| Transformative Adaptation | 1. Propensity for transformation | 3 | 0.840 | 0.847 | — | 0.120 | 0.026 | 0.245 | — |

| 2. Distress to change | 3 | 0.800 | 0.801 | −0.158 | — | −0.478 | −0.314 | — | |

| 3. Adaptability | 3 | 0.733 | 0.745 | 0.035 | 0.560 | — | 0.522 | — | |

| 4. Fullness of the experience | 3 | 0.617 | 0.645 | 0.242 | 0.336 | 0.590 | — | — | |

| Part C | N = 5 | 20 | 0.794 | 0.840 | |||||

| Work Attitude | 1. Social Service and Care | 4 | 0.945 | 0.945 | — | −0.093 | 0.290 | 0.290 | 0.155 |

| 2. Administrative and Office Works | 4 | 0.932 | 0.934 | 0.079 | — | 0.132 | 0.132 | 0.044 | |

| 3. Entrepreneurship | 4 | 0.922 | 0.925 | 0.042 | 0.062 | — | 0.137 | 0.026 | |

| 4. Customer Service and Hospitality | 4 | 0.919 | 0.923 | 0.215 | 0.129 | 0.129 | — | 0.338 | |

| 5. Manual activities | 4 | 0.887 | 0.888 | 0.136 | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.287 | — | |

| χ2 | df | p | CMIN/DF | GFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Models Comparison | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part A: Evolutionary Thrust | |||||||||||||

| Correlational Model | 169.923 | 80 | <0.001 | 2.124 | 0.935 | 0.945 | 0.958 | 0.060 | 0.065 | ||||

| Unifactorial Model | 1203.011 | 90 | <0.001 | 13.367 | 0.636 | 0.391 | 0.478 | 0.198 | 0.149 | ||||

| M1-M2 | 1033.088 | 10 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Part B: Transformative Adaptation | |||||||||||||

| Correlational Model | 165.171 | 48 | <0.001 | 3.441 | 0.927 | 0.863 | 0.900 | 0.088 | 0.069 | ||||

| Unifactorial Model | 694.197 | 54 | <0.001 | 12.855 | 0.715 | 0.333 | 0.455 | 0.194 | 0.156 | ||||

| M1-M2 | 529.026 | 6 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Part C: Work Attitude | |||||||||||||

| Correlational Model | 561.338 | 160 | <0.001 | 3.508 | 0.841 | 0.912 | 0.926 | 0.089 | 0.044 | ||||

| Unifactorial Model | 4392.872 | 170 | <0.001 | 25.84 | 0.417 | 0.129 | 0.221 | 0.280 | 0.253 | ||||

| M1-M2 | 4227.701 | 10 | <0.001 | ||||||||||

| Part A: Evolutionary Thrust | Part B: Transformative Adaptation | Part C: Work Attitude | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | Total | B1 | B2 | B3 | B4 | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | |

| Satisfaction with life (SWLS) | 0.526 ** (0.609) | 0.612 ** (0.695) | 0.189 ** (0.219) | 0.452 ** (0.520) | 0.490 ** (0.574) | −0.275 ** (0.313) | 0.001 (0.071) | −0.489 ** (0.566) | −0.186 ** (0.222) | 0.279 ** (0.339) | 0.224 ** (0.291) | −0.017 (0.018) | 0.060 (0.067) | 0.068 (0.079) | −0.031 (0.035) | 0.034 (0.041) |

| Career Adaptability (CAAS) | 0.613 ** (0.697) | 0.418 ** (0.456) | 0.287 ** (0.322) | 0.502 ** (0.559) | 0.444 ** (0.502) | 0.165 ** (0.260) | 0.353 ** (0.481) | −0.016 (0.017) | −0.135 ** (0.158) | 0.474 ** (0.575) | 0.429 ** (0.568) | 0.035 (0.040) | 0.090 * (0.097) | 0.193 ** (0.207) | 0.036 (0.039) | 0.037 (0.043) |

| Concern (CAAS) | 0.507 ** (0.587) | 0.314 ** (0.354) | 0.187 ** (0.213) | 0.399 ** (0.457) | 0.362 ** (0.422) | 0.244 ** (0.354) | 0.230 ** (0.470) | 0.067 (0.076) | 0.012 (0.014) | 0.308 ** (0.419) | 0.304 ** (0.381) | 0.002 (0.003) | 0.087 * (0.095) | 0.231 ** (0.255) | −0.022 (0.026) | −0.046 (0.050) |

| Control (CAAS) | 0.504 ** (0.615) | 0.397 ** (0.457) | 0.235 ** (0.282) | 0.464 ** (0.556) | 0.386 ** (0.464) | −0.010 (0.045) | 0.274 ** (0.276) | −0.123 ** (0.138) | −0.198 ** (0.240) | 0.419 ** (0.437) | 0.316 ** (0.540) | −0.001 (0.000) | 0.050 (0.057) | 0.096 * (0.116) | 0.085 * (0.098) | 0.086 * (0.102) |

| Curiosity (CAAS) | 0.532 ** (0.639) | 0.327 ** (0.372) | 0.289 ** (0.335) | 0.404 ** (0.470) | 0.374 ** (0.443) | 0.203 ** (0.323) | 0.388 ** (0.553) | 0.055 (0.066) | −0.138 ** (0.166) | 0.438 ** (0.635) | 0.463 ** (0.551) | 0.093 * (0.103) | 0.039 (0.045) | 0.190 ** (0.216) | 0.040 (0.043) | 0.051 (0.059) |

| Confidence (CAAS) | 0.508 ** (0.595) | 0.368 ** (0.413) | 0.260 ** (0.295) | 0.416 ** (0.476) | 0.365 ** (0.426) | 0.096 * (0.164) | 0.301 ** (0.381) | −0.067 (0.076) | −0.150 ** (0.177) | 0.438 ** (0.491) | 0.361 ** (0.543) | 0.030 (0.032) | 0.123 ** (0.134) | 0.114 ** (0.130) | 0.028 (0.030) | 0.046 (0.051) |

| General Self-Efficacy (GSES) | 0.445 ** (0.514) | 0.427 ** (0.479) | 0.124 ** (0.144) | 0.403 ** (0.468) | 0.388 ** (0.455) | −0.080 * (0.061) | 0.380 ** (0.505) | −0.131 ** (0.148) | −0.363 ** (0.429) | 0.505 ** (0.624) | 0.317 ** (0.417) | −0.003 (0.005) | 0.059 (0.067) | 0.247 ** (0.278) | 0.033 (0.035) | 0.066 (0.073) |

| Insight Orientation (IOS) | 0.531 ** (0.673) | 0.438 ** (0.533) | 0.277 ** (0.339) | 0.445 ** (0.551) | 0.362 ** (0.457) | 0.043 (0.107) | 0.341 ** (0.496) | −0.038 (0.053) | −0.186 ** (0.240) | 0.454 ** (0.600) | 0.371 ** (0.529) | 0.085 * (0.100) | 0.055 (0.063) | 0.222 ** (0.266) | 0.073 (0.082) | 0.062 (0.074) |

| Resilience (CD-RISC-10) | 0.483 ** (0.588) | 0.473 ** (0.544) | 0.246 ** (0.296) | 0.382 ** (0.456) | 0.377 ** (0.454) | −0.082 * (0.050) | 0.442 ** (0.611) | −0.142 ** (0.157) | −0.435 ** (0.530) | 0.555 ** (0.707) | 0.374 ** (0.515) | 0.103 ** (0.119) | 0.049 (0.051) | 0.212 ** (0.246) | 0.100 * (0.110) | 0.076 (0.086) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gori, A.; Topino, E. META—Measurement for Evolution, Transformation, and Autorealization: A New Assessment Protocol. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070942

Gori A, Topino E. META—Measurement for Evolution, Transformation, and Autorealization: A New Assessment Protocol. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):942. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070942

Chicago/Turabian StyleGori, Alessio, and Eleonora Topino. 2025. "META—Measurement for Evolution, Transformation, and Autorealization: A New Assessment Protocol" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070942

APA StyleGori, A., & Topino, E. (2025). META—Measurement for Evolution, Transformation, and Autorealization: A New Assessment Protocol. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 942. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070942