Emotion Regulation Strategies and Psychological Well-Being in Emerging Adulthood: Mediating Role of Optimism and Self-Esteem in a University Student Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Emerging Adulthood: A New Developmental Stage

1.2. Psychological Well-Being in Emerging Adulthood

1.3. Emotion Regulation Strategies and Mental Health

1.4. Personality Traits: Self-Esteem and Optimism

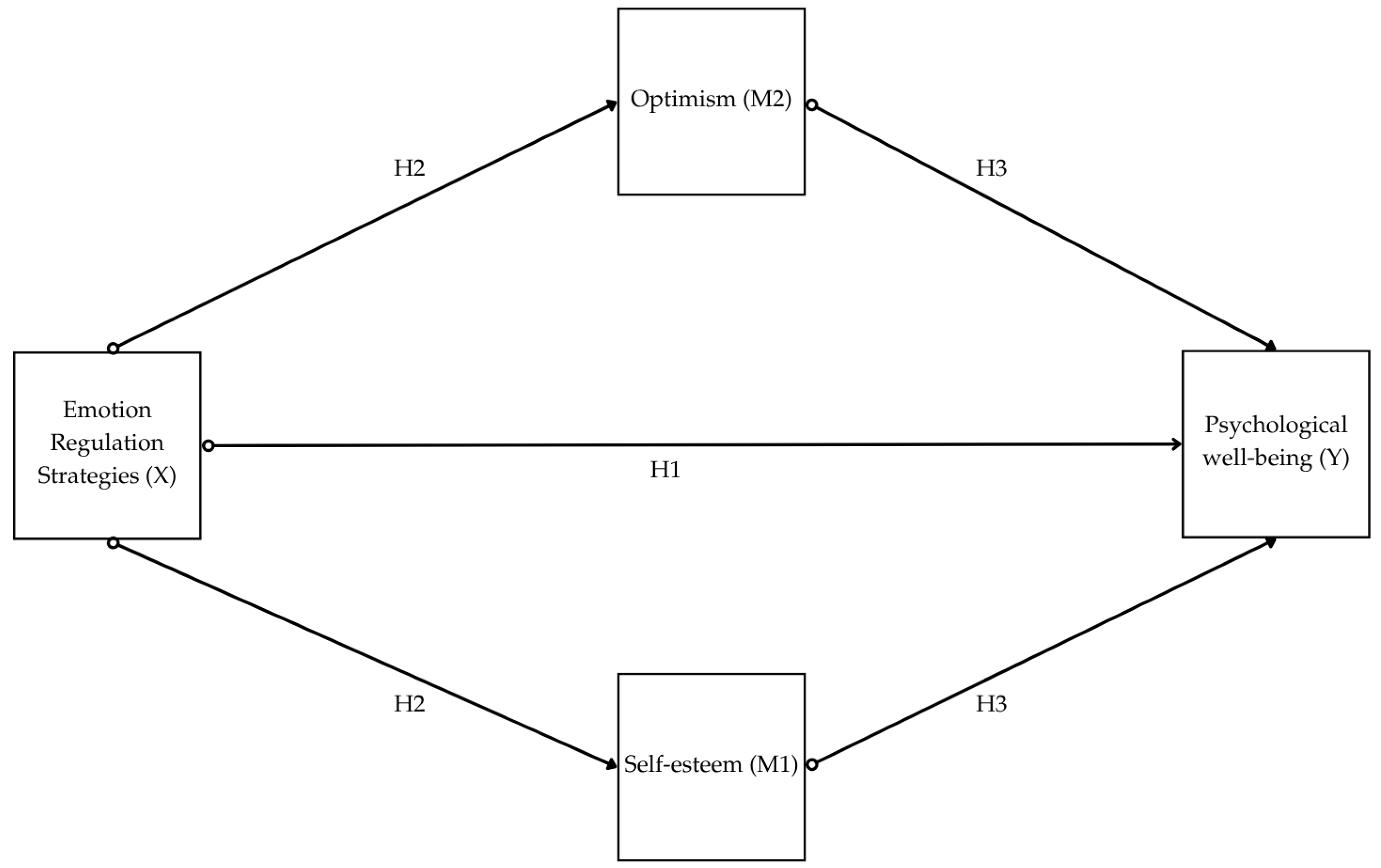

1.5. Objective and Hypotheses of the Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

3.2. Model Fit

3.3. Direct Effects

3.4. Indirect Effects

3.5. Total Effects

4. Discussion

Strengths, Implications and Limits

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2016). College Students as Emerging Adults. Emerging Adulthood, 4(3), 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2018). Conceptual foundations of emerging adulthood. In J. L. Murray, & J. J. Arnett (Eds.), Emerging adulthood and higher education (pp. 11–24). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J., & Eisenberg, N. (2007). Introduction to the special section: Emerging adulthood around the world. Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 66–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J., & Mitra, D. (2020). Are the features of emerging adulthood developmentally distinctive? A comparison of ages 18–60 in the United States. Emerging Adulthood, 8(5), 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggio, S., Studer, J., Iglesias, K., Daeppen, J.-B., & Gmel, G. (2017). Emerging adulthood: A time of changes in psychosocial well-being. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 40(4), 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer Pich, N., Sánchez Gómez, M., & García-Palacios, A. (2018). Relación entre la regulación emocional y la autoestima. Àgora de Salut, 5, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, A. M. (2022). Competencias emocionales y bienestar subjetivo en adultos emergentes. Universidad de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Balzarotti, S., Biassoni, F., Villani, D., Prunas, A., & Velotti, P. (2016). Individual differences in cognitive emotion regulation: Implications for subjective and psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranski, E., Sweeny, K., Gardiner, G., & Funder, D. C. (2021). International optimism: Correlates and consequences of dispositional optimism across 61 countries. Journal of Personality, 89(2), 288–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, A. D., & Soares, A. B. (2023). Well-being, character strengths, and depression in emerging adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1238105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18(6), 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2021). Optimism. In Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research (pp. 1–6). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cashin, A. G., McAuley, J. H., & Lee, H. (2022). Advancing the reporting of mechanisms in implementation science: A guideline for reporting mediation analyses (AGReMA). Implementation Research and Practice, 3, 263348952211055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cobo-Rendón, R. C., Pérez-Villalobos, M. V., Díaz-Mujica, A. E., & García-Álvarez, D. J. (2020). Revisión sistemática sobre modelos multidimensionales del bienestar y su medición en estudiantes universitarios. Formación Universitaria, 13(2), 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (2022). Marty, me, and early positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(2), 149–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, D., Rodríguez-Carvajal, A. B., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Gallardo, I., Valle, C., & van Dierendonck, D. (2006). Adaptación española de las escalas de bienestar psicológico de Ryff. Psicothema, 18(3), 572–577. [Google Scholar]

- Duy, B., & Yıldız, M. A. (2019). The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between optimism and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 38(6), 1456–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckland, N. S., & Berenbaum, H. (2023). Clarity of emotions and goals: Exploring associations with subjective well-being across adulthood. Affective Science, 4(2), 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, C. (2020). El optimismo y su relación con el bienestar psicológico. Revista Científica Arbitrada de La Fundación MenteClara, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E., & Paino, M. (2008). Construction and validation of the oviedo infrequency scale in Spanish adolescents [Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad de Oviedo]. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, T., & Tavares, D. (2011). Influência da autoestima, da regulação emocional e do gênero no bem-estar subjetivo e psicológico de adolescentes. Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo), 38(5), 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangemi, A., Dahò, M., & Mancini, F. (2021). Emotion reasoning and psychopathology. Brain Sciences, 11(4), 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangemi, A., Gragnani, A., Dahò, M., & Buonanno, C. (2019). Reducing probability overestimation of threatening events: An Italian study on the efficacy of cognitive techniques in non-clinical subjects. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 16(3), 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2006). Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire—Development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Personality and Individual Differences, 41(6), 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellatly, R., & Beck, A. T. (2016). Catastrophic thinking: A transdiagnostic process across psychiatric disorders. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 40(4), 441–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, J. J. (2024). Conceptual foundations of emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross, & B. Q. Ford (Eds.), Handbook of emotion regulation (3rd ed., pp. 3–12, 605p). The Guilford Press. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/books/conceptual-foundations-emotion-regulation/docview/2938543587/se-2?accountid=14777 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Gross, J. J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haga, S. M., Kraft, P., & Corby, E.-K. (2009). Emotion regulation: Antecedents and well-being outcomes of cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression in cross-cultural samples. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(3), 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M. T., Letcher, P., Sanson, A., Smart, D., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2009). Positive development in emerging adulthood. Australian Journal of Psychology, 61(2), 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herce Fernández, R. (2020). Interdisciplinariedad y transdisciplinariedad en la investigación de Carol Ryff. Naturaleza y Libertad. Revista de Estudios Interdisciplinares, 14(2), 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgado-Tello, F. P., Amor, P. J., Lasa-Aristu, A., Domínguez-Sánchez, F. J., & Delgado, B. (2018). Two new brief versions of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire and its relationships with depression and anxiety. Anales de Psicología, 34(3), 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAVA. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 79(4), 2191–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraiss, J. T., ten Klooster, P. M., Moskowitz, J. T., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2020). The relationship between emotion regulation and well-being in patients with mental disorders: A meta-analysis. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 102, 152189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Cashin, A. G., Lamb, S. E., Hopewell, S., Vansteelandt, S., VanderWeele, T. J., MacKinnon, D. P., Mansell, G., Collins, G. S., Golub, R. M., McAuley, J. H., Localio, A. R., van Amelsvoort, L., Guallar, E., Rijnhart, J., Goldsmith, K., Fairchild, A. J., Lewis, C. C., Kamper, S. J., … Henschke, N. (2021). A guideline for reporting mediation analyses of randomized trials and observational studies. JAMA, 326(11), 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumley, T., Diehr, P., Emerson, S., & Chen, L. (2002). The importance of the normality assumption in large public health data sets. Annual Review of Public Health, 23(1), 151–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, J. S. R., Staten, R., Hall, L. A., & Lennie, T. A. (2012). The relationship among young adult college students’ depression, anxiety, stress, demographics, life satisfaction, and coping styles. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(3), 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S., Arya, Y., Pandey, R., & Singh, T. (2022). The mediating role of emotion regulation in the emotion complexity and subjective well-being relationship. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 10(4), 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Albo, J., Núñez, J. L., Navarro, J. G., & Grijalvo, F. (2007). The rosenberg self-esteem scale: Translation and validation in University Students [article]. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavani, J. B., & Colombo, D. (2023). Appreciation and rumination, not problem solving and avoidance, mediate the effect of optimism on emotion wellbeing. Personality and Individual Differences, 205, 112094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrosa, I., Celis-Atenas, K., Suárez-Álvarez, J., García-Cueto, E., & Muñiz, J. (2015). Cuestionario para la evaluación del optimismo: Fiabilidad y evidencias de validez. Terapia Psicológica, 33(2), 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, T., Summers, R. F., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2023). Positive psychology model of mental function and behavior. In Tasman’s psychiatry (pp. 1–24). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reifman, A., Arnett, J. J., & Colwell, M. J. (2007). Emerging adulthood: Theory, assessment and application. Journal of Youth Development, 2(1), 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B. W., & Davis, J. P. (2016). Young adulthood is the crucible of personality development. Emerging Adulthood, 4(5), 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B. W., & Yoon, H. J. (2022). Personality psychology. Annual Review of Psychology, 73(1), 489–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Menchón, M., Orgilés, M., Fernández-Martínez, I., Espada, J. P., & Morales, A. (2021). Rumination, catastrophizing, and other-blame: The cognitive-emotion regulation strategies involved in anxiety-related life interference in anxious children. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. (2016). The measurement of self-esteem. In M. Rosenberg (Ed.), Society and the adolescent self-image (pp. 16–38). Princton University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Beyond ponce de Leon and life satisfaction: New directions in quest of successful ageing. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 12(1), 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryff, C. D. (2023). In pursuit of eudaimonia: Past advances and future directions. In Human flourishing (pp. 9–31). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanjivani, D. I., & Ramdas, K. (2024). Optimism and psychological well-being among young adults. International Journal of Indian Psychȯlogy, 12(1), 2167–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi Çakar, F. (2014). The effect of automatic thoughts on hopelessness: Role of self-esteem as a mediator. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14(5), 1682–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4(3), 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seager, W. (2009). Philosophical accounts of self-awareness and introspection. In Encyclopedia of consciousness (pp. 187–199). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. (2019). Positive psychology: A personal history. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, T. (2016). Constructing adulthood: Markers of adulthood and well-being among emerging adults. Emerging Adulthood, 4(3), 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, C., Dockray, S., & McMahon, J. (2024). The relationship between cognitive reappraisal and psychological well-being during early adolescence: A scoping review. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 45(1), 104–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupar-Rutenfrans, S., Fokke, A., Bye, S., Padilla, E., Kalibatseva, Z., Batkhina, A., Ryabichenko, T., Bushina, E., Varaeva, N., Helmy, M., Kowalczyk, M., Danuta Liberska, H., Uka, F., & Papageorgopoulou, P. (2024). Subjective well-being: A pilot study on the importance of emotion regulation, gender identity and sexuality. Psychology & Sexuality, 15(4), 645–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamhane, A. (2020). Multiple linear regression: Variable selection and model building (pp. 159–180). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velert-Jiménez, S., Valero-Moreno, S., Gil-Gómez, J.-A., Pérez-Marín, M., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2025). EmoWELL: Effectiveness of a serious game for emotion regulation in emerging adulthood. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1561418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verzeletti, C., Zammuner, V. L., Galli, C., & Agnoli, S. (2016). Emotion regulation strategies and psychosocial well-being in adolescence. Cogent Psychology, 3(1), 1199294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, R., Hong, X., Wei, G., Xu, X., & Yuan, J. (2022). Differential effects of optimism and pessimism on adolescents’ subjective well-being: Mediating roles of reappraisal and acceptance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Sk | Ks | Min | Max | α | ω | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive strategies | Planning | 7.67 | 1.58 | −0.48 | 0.04 | 2 | 10 | 0.65 | N/A |

| Acceptance | 7.98 | 1.41 | −0.52 | 0.37 | 2 | 10 | 0.73 | N/A | |

| Positive reappraisal | 6.39 | 2.12 | −0.02 | −0.69 | 2 | 10 | 0.84 | N/A | |

| Putting into perspective | 6.94 | 1.61 | 0.0 | −0.46 | 2 | 10 | 0.51 | N/A | |

| Positive refocusing | 5.62 | 1.93 | 0.07 | −0.53 | 2 | 10 | 0.73 | N/A | |

| Maladaptive strategies | Rumination | 7.01 | 1.70 | −0.25 | −0.34 | 2 | 10 | 0.63 | N/A |

| Catastrophizing | 5.73 | 1.88 | 0.18 | −0.58 | 2 | 10 | 0.79 | N/A | |

| Self-blame | 6.45 | 1.88 | −0.19 | −0.32 | 2 | 10 | 0.81 | N/A | |

| Other-blame | 4.68 | 1.65 | 0.40 | 0.07 | 2 | 10 | 0.85 | N/A | |

| Psychological well-being | Self-acceptance | 16.77 | 4.23 | −0.23 | −0.52 | 4 | 24 | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Positive relations | 23.05 | 5.16 | −0.63 | −0.21 | 7 | 30 | 0.81 | 0.81 | |

| Autonomy | 24.10 | 5.81 | −0.31 | −0.48 | 7 | 36 | 0.78 | 0.77 | |

| Environmental mastery | 20.45 | 4.12 | −0.08 | −0.41 | 8 | 30 | 0.65 | 0.63 | |

| Purpose in life | 20.36 | 5.24 | −0.08 | −0.62 | 6 | 30 | 0.85 | 0.85 | |

| Personal growth | 19.55 | 3.44 | −0.57 | −0.19 | 8 | 24 | 0.71 | 0.73 | |

| Mediation variables | Self-esteem | 31.10 | 5.72 | −0.48 | −0.36 | 11 | 40 | 0.90 | 0.90 |

| Optimism | 35.19 | 6.76 | −0.66 | 0.13 | 12 | 45 | 0.90 | 0.90 | |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rumination | — | |||||||||||||||

| Catastrophizing | 0.52 *** | — | ||||||||||||||

| Self-blame | 0.32 *** | 0.27 *** | — | |||||||||||||

| Other-blame | 0.07 * | 0.25 *** | −0.10 ** | — | ||||||||||||

| Planning | −0.08 * | −0.27 *** | −0.07 * | 0.02 | — | |||||||||||

| Acceptance | −0.063 | −0.24 *** | −0.05 | −0.04 | 0.39 *** | — | ||||||||||

| Positive reappraisal | −0.25 *** | −0.45 *** | −0.09 ** | −0.13 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.33 *** | — | |||||||||

| Putting into perspective | −0.12 *** | −0.11 ** | 0.06 | −0.00 | 0.22 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.28 *** | — | ||||||||

| Positive refocusing | −0.22 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.14 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.31 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.26 *** | — | |||||||

| Self-acceptance | −0.17 *** | −0.40 *** | −0.22 *** | −0.07 * | 0.50 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.18 *** | 0.27 *** | — | ||||||

| Positive relations | −0.10 ** | −0.24 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.12 *** | 0.19 *** | 0.08 * | 0.19 *** | 0.05 | 0.08 * | 0.41 *** | — | |||||

| Autonomy | −0.25 *** | −0.35 *** | −0.23 *** | −0.06 | 0.32 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.02 | 0.14 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.29 *** | — | ||||

| Environmental mastery | −0.23 *** | −0.40 *** | −0.14 *** | −0.15 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.12 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.72 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.37 *** | — | |||

| Purpose in life | −0.14 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.14 *** | −0.05 | 0.47 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.17 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.78 *** | 0.28 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.72 *** | — | ||

| Personal growth | −0.02 | −0.22 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.06 | 0.39 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.09 ** | 0.09 * | 0.58 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.50 *** | 0.54 *** | — | |

| Self-esteem | −0.23 *** | −0.43 *** | −0.29 *** | −0.11 ** | 0.43 *** | 0.24 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.10 ** | 0.22 *** | 0.79 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.66 *** | 0.63 *** | 0.53 *** | — |

| Optimism | −0.27 *** | −0.47 *** | −0.21 *** | −0.12 *** | 0.51 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.16 *** | 0.27 *** | 0.75 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.78 *** |

| Interval | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (X) | (M) | (Y) | Effect Type | Est | Std | Z-Value | p | Low | Up |

| Positive reappraisal | N/A | Self-acceptance | Direct | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.08 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| Positive reappraisal | N/A | Environmental mastery | Direct | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.43 | 0.66 | −0.02 | 0.04 |

| Positive reappraisal | N/A | Purpose in life | Direct | 0.03 | 0.02 | 2.12 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 |

| Planning | N/A | Self-acceptance | Direct | 0.07 | 0.02 | 4.70 | <0.00 | 0.04 | 0.10 |

| Planning | N/A | Environmental mastery | Direct | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.19 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.08 |

| Planning | N/A | Purpose in life | Direct | 0.08 | 0.02 | 4.10 | <0.00 | 0.04 | 0.12 |

| Catastrophizing | N/A | Self-acceptance | Direct | 0.00 | 0.01 | −0.10 | 0.91 | −0.03 | 0.02 |

| Catastrophizing | N/A | Environmental mastery | Direct | −0.04 | 0.02 | −2.23 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| Catastrophizing | N/A | Purpose in life | Direct | 0.05 | 0.02 | 3.28 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Positive reappraisal | Self-esteem | Self-acceptance | Indirect | 0.04 | 0.01 | 4.57 | <0.00 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

| Positive reappraisal | Optimism | Self-acceptance | Indirect | 0.03 | 0.01 | 5.06 | <0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Positive reappraisal | Self-esteem | Environmental mastery | Indirect | 0.03 | 0.01 | 4.16 | <0.00 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Positive reappraisal | Optimism | Environmental mastery | Indirect | 0.04 | 0.01 | 5.22 | <0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Positive reappraisal | Self-esteem | Purpose in life | Indirect | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.96 | <0.00 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Positive reappraisal | Optimism | Purpose in life | Indirect | 0.05 | 0.01 | 6.11 | <0.00 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Planning | Self-esteem | Self-acceptance | Indirect | 0.09 | 0.01 | 6.65 | <0.00 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Planning | Optimism | Self-acceptance | Indirect | 0.05 | 0.01 | 5.64 | <0.00 | 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Planning | Self-esteem | Environmental mastery | Indirect | 0.06 | 0.01 | 5.18 | <0.00 | 0.04 | 0.08 |

| Planning | Optimism | Environmental mastery | Indirect | 0.07 | 0.01 | 5.70 | <0.00 | 0.05 | 0.10 |

| Planning | Self-esteem | Purpose in life | Indirect | 0.04 | 0.01 | 4.52 | <0.00 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Planning | Optimism | Purpose in life | Indirect | 0.09 | 0.01 | 7.37 | <0.00 | 0.07 | 0.12 |

| Catastrophizing | Self-esteem | Self-acceptance | Indirect | −0.08 | 0.01 | −7.61 | <0.00 | −0.10 | −0.06 |

| Catastrophizing | Optimism | Self-acceptance | Indirect | −0.04 | 0.01 | −5.35 | <0.00 | −0.05 | −0.03 |

| Catastrophizing | Self-esteem | Environmental mastery | Indirect | −0.05 | 0.01 | −5.73 | <0.00 | −0.06 | −0.03 |

| Catastrophizing | Optimism | Environmental mastery | Indirect | −0.05 | 0.01 | −5.54 | <0.00 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| Catastrophizing | Self-esteem | Purpose in life | Indirect | −0.04 | 0.01 | −4.96 | <0.00 | −0.05 | −0.02 |

| Catastrophizing | Optimism | Purpose in life | Indirect | −0.07 | 0.01 | −6.76 | <0.00 | −0.09 | −0.05 |

| Positive reappraisal | N/A | Self-acceptance | Total | 0.10 | 0.02 | 5.90 | <0.00 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Positive reappraisal | N/A | Environmental mastery | Total | 0.07 | 0.02 | 4.20 | <0.00 | 0.04 | 0.11 |

| Positive reappraisal | N/A | Purpose in life | Total | 0.10 | 0.02 | 5.96 | <0.00 | 0.07 | 0.14 |

| Planning | N/A | Self-acceptance | Total | 0.21 | 0.02 | 10.16 | <0.00 | 0.17 | 0.25 |

| Planning | N/A | Environmental mastery | Total | 0.16 | 0.02 | 7.50 | <0.00 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Planning | N/A | Purpose in life | Total | 0.21 | 0.02 | 9.63 | <0.00 | 0.17 | 0.26 |

| Catastrophizing | N/A | Self-acceptance | Total | −0.11 | 0.02 | −6.72 | <0.00 | −0.15 | −0.08 |

| Catastrophizing | N/A | Environmental mastery | Total | −0.13 | 0.02 | −7.36 | <0.00 | −0.17 | −0.10 |

| Catastrophizing | N/A | Purpose in life | Total | −0.05 | 0.02 | −2.78 | 0.00 | −0.09 | −0.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanchez-Sanchez, H.; Schoeps, K.; Montoya-Castilla, I. Emotion Regulation Strategies and Psychological Well-Being in Emerging Adulthood: Mediating Role of Optimism and Self-Esteem in a University Student Sample. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070929

Sanchez-Sanchez H, Schoeps K, Montoya-Castilla I. Emotion Regulation Strategies and Psychological Well-Being in Emerging Adulthood: Mediating Role of Optimism and Self-Esteem in a University Student Sample. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):929. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070929

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanchez-Sanchez, Hugo, Konstanze Schoeps, and Inmaculada Montoya-Castilla. 2025. "Emotion Regulation Strategies and Psychological Well-Being in Emerging Adulthood: Mediating Role of Optimism and Self-Esteem in a University Student Sample" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070929

APA StyleSanchez-Sanchez, H., Schoeps, K., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2025). Emotion Regulation Strategies and Psychological Well-Being in Emerging Adulthood: Mediating Role of Optimism and Self-Esteem in a University Student Sample. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 929. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070929