The Influence of Spatial Distance and Trade-Off Salience on Ethical Decision-Making: An Eye-Tracking Study Based on Embodied Cognition

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Construal Level and Embodied Cognition

1.2. Construal Level and Ethical Decision-Making

1.3. The Influence of Trade-Off Salience on Ethical Decision-Making

2. Experiment 1: The Influence of Spatial Distance on Ethical Decision-Making

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Apparatus

2.3. Experimental Design

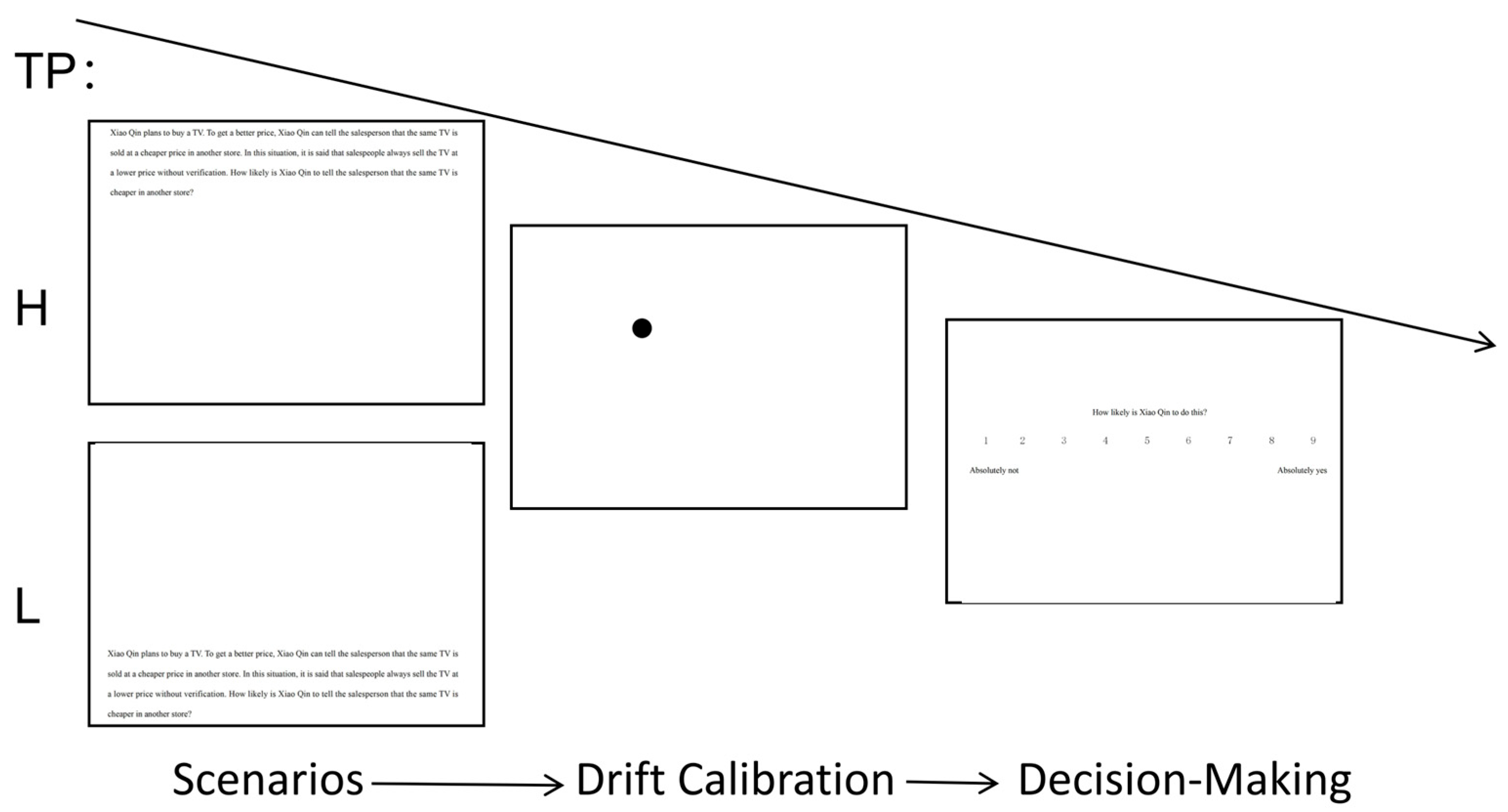

2.4. Experimental Materials and Procedures

2.5. Results and Analysis

- (1)

- Ethical Decision-Making Outcomes

- (2)

- Eye-Tracking Data Outcomes

2.6. Discussion

3. Experiment 2: The Influence of Spatial Distance and Trade-Off Salience Level on Ethical Decision-Making

3.1. Participants

3.2. Experimental Apparatus

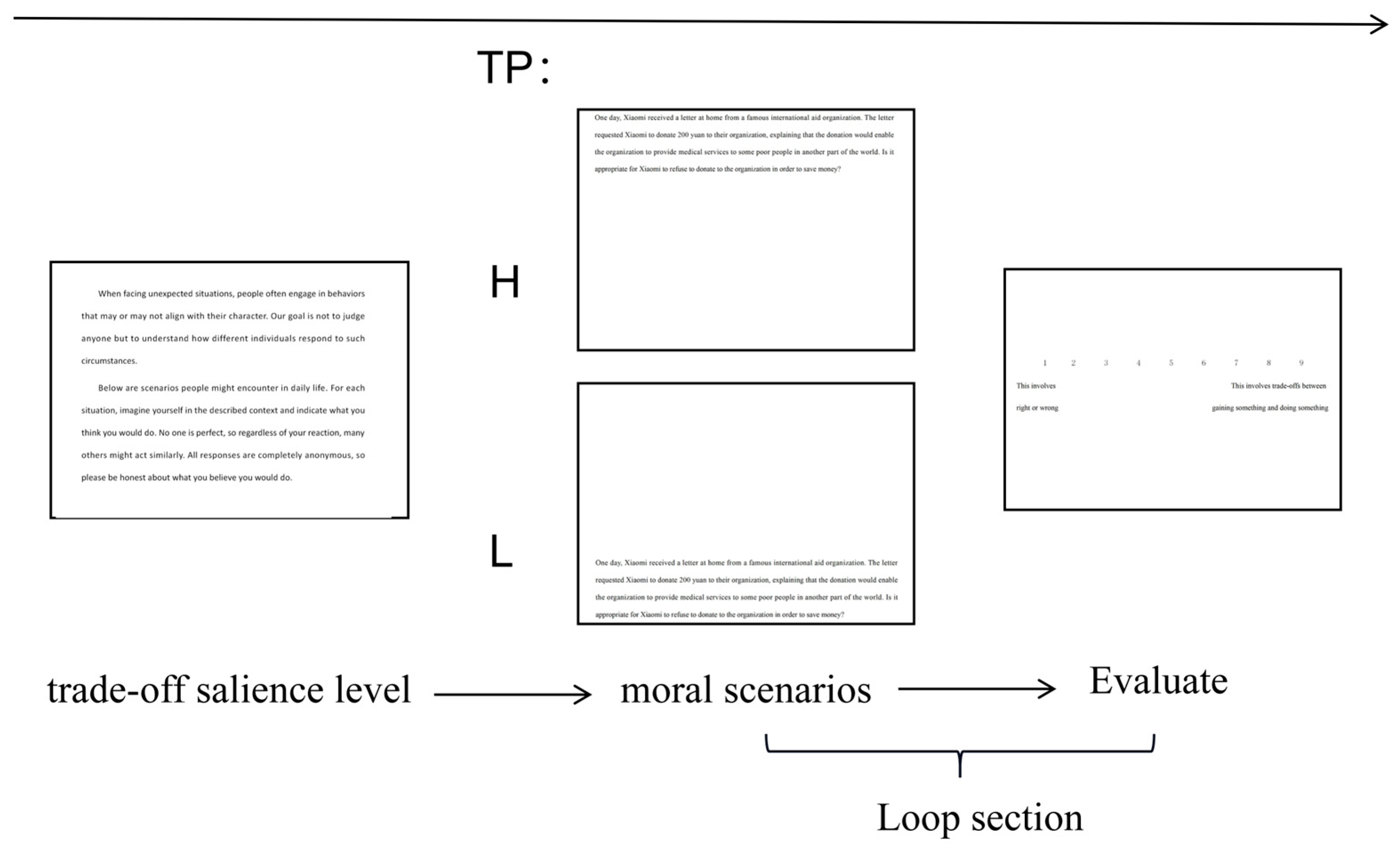

3.3. Experimental Design

3.4. Experimental Materials and Procedures

3.5. Pre-Test

3.6. Results and Analysis

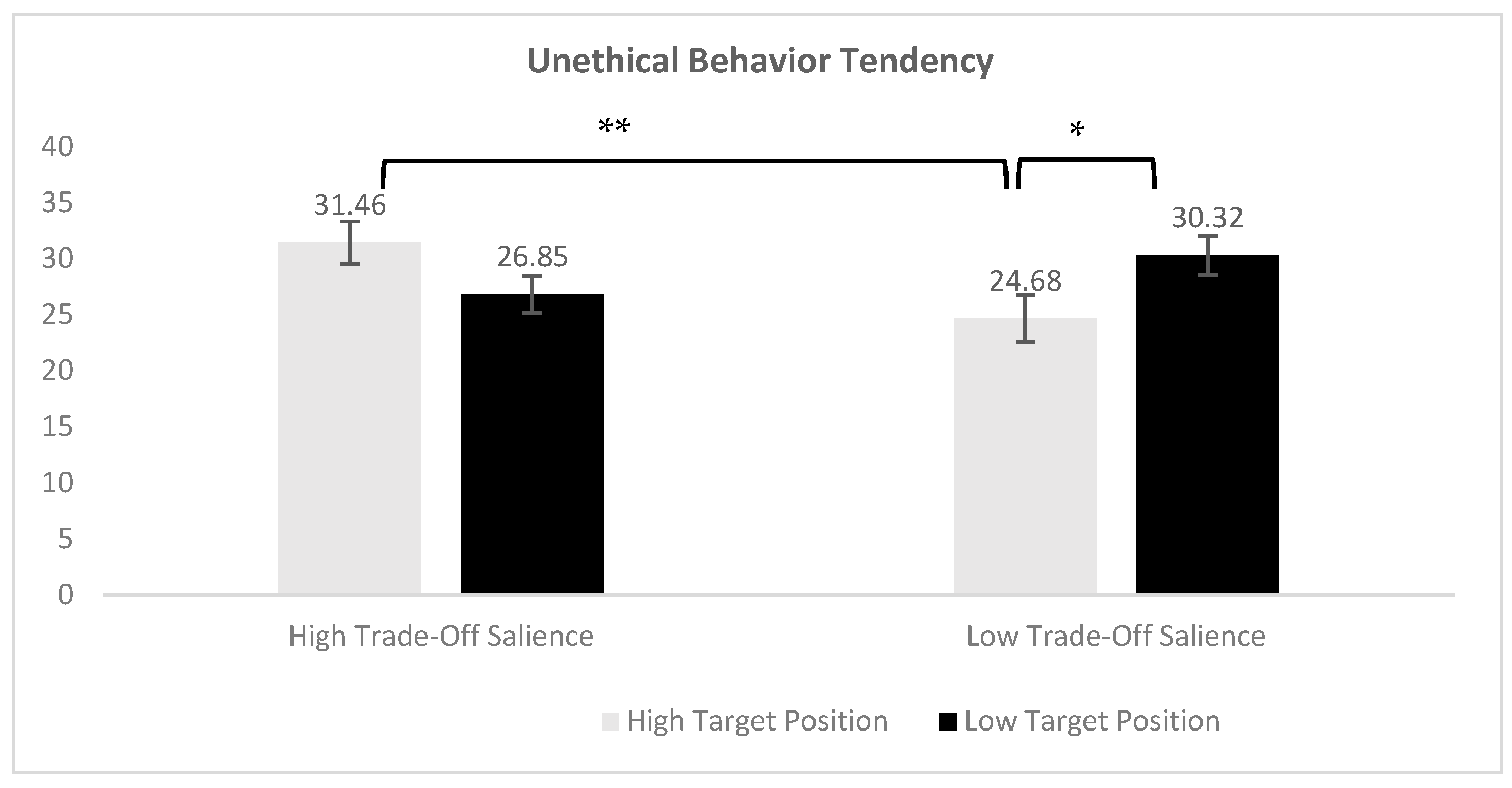

- (1)

- Ethical Decision-Making Outcomes

- (2)

- Eye-Tracking Data Outcomes

3.7. Discussion

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings

4.2. Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TP | Target Position |

| TS | Trade-Off Salience |

| TFD | Total Fixation Duration |

| FDP | Fixation Duration Percentage |

| FC | Fixation Counts |

| FCP | Fixation Counts Percentage |

| MFD | Mean Fixation Duration |

| FFD | First Fixation Duration |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Appendix A.2

References

- Aberg, K. C., Toren, I., & Paz, R. (2022). A neural and behavioral trade-off between value and uncertainty underlies exploratory decisions in normative anxiety. Mol Psychiatry, 27, 1573–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affinito, S. J., Hofmann, D. A., & Keeney, J. E. (2025). Out of sight, out of mind: How high-level construals can decrease the ethical framing of risk-mitigating behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 110(2), 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerström, J., & Björklund, F. (2009). Moral concerns are greater for temporally distant events and are moderated by value strength. Social Cognition, 27(2), 260–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alper, S., & Yilmaz, O. (2020). Does an abstract mind-set increase the internal consistency of moral attitudes and strengthen individualizing foundations? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(3), 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, N. B. (2021). How interruptions influence our thinking and the role of psychological distance. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 20(1), 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, N. B., & Jiao, J. (2023). Responses to ethical scenarios: The impact of trade-off salience on competing construal level effects. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(3), 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, E., & Greene, J. D. (2012). You see, the ends don’t justify the means: Visual imagery and moral judgment. Psychological Science, 23(8), 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canessa, N. (2025). Combined tDCS-fMRI evidence on the exploration-exploitation trade-off in decision-making. Brain Stimulation: Basic, Translational, and Clinical Research in Neuromodulation, 18(1), 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, P., Fernández, I., Muñoz, D., & Caballero, A. (2020). Using abstractness to confront challenges: How the abstract construal level increases people’s willingness to perform desirable but demanding actions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 26(2), 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A., Treviño, L. K., & Humphrey, S. E. (2020). Ethical champions, emotions, framing, and team ethical decision making. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(3), 245–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, J. L. (2013). A review of the empirical ethical decision-making literature: 2004–2011. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 221–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X., Li, Z., & Gibson, J. (2016). A review on trade-off analysis of ecosystem services for sustainable land-use management. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 16(7), 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeTienne, K. B., Ellertson, C. F., Ingerson, M.-C., & Dudley, W. R. (2021). Moral development in business ethics: An examination and critique. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(3), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duc, C., Hanselmann, M., Boesiger, P., & Tanner, C. (2013). Sacred values: Trade-off type matters. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 6(4), 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyal, T., Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2008). Judging near and distant virtue and vice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1204–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, M. (2021). Embodied cognition: Dimensions, domains and applications. Adaptive Behavior, 29(1), 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149−1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, S., & Glöckner, A. (2015). Attention and moral behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K. (2008). Seeing the forest beyond the trees: A construal-Level approach to self-control. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(3), 1475−1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H., & Medin, D. L. (2012). Construal levels and moral judgment: Some complications. Judgment and Decision Making, 7, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J., Haidt, J., Koleva, S., Motyl, M., Iyer, R., Wojcik, S. P., & Ditto, P. H. (2013). Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. In P. Devine, & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 55–130). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J. D., Nystrom, L. E., Engell, A. D., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2004). The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron, 44(2), 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. D., Sommerville, R. B., Nystrom, L. E., Darley, J. M., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science, 293(5537), 2105–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, R. A., Barbato, M. T., Sznycer, D., & Cosmides, L. (2022). A moral trade-off system produces intuitive judgments that are rational and coherent and strike a balance between conflicting moral values. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(42), e2214005119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanselmann, M., & Tanner, C. (2008). Taboos and conflicts in decision making: Sacred values, decision difficulty, and emotions. Judgment and Decision Making, 3(1), 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, A., & Woodall, T. (2019). Everything flows: A pragmatist perspective of trade-offs and value in ethical consumption. Journal of Business Ethics, 157, 893–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, M., Tamborini, R., & Ryffel, F. A. (2021). Between a rock and a hard place. Journal of Media Psychology, 33(3), 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, K., Nyström, N., Andersson, R., Dewhurst, R., Jarodzka, H., & Van de Weijer, J. (2011). Eye tracking: A comprehensive guide to methods and measures. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, T. M. (1991). Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review, 16(2), 366–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, M. C., & Chugh, D. (2009). Bounded ethicality: The perils of loss framing. Psychological Science, 20(3), 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U., Zhu, M., & Kalra, A. (2011). When trade-offs matter: The effect of choice construal on context effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(1), 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouchaki, M., Smith-Crowe, K., Brief, A. P., & Sousa, C. (2013). Seeing green: Mere exposure to money triggers a business decision frame and unethical outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121(1), 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Chu, X. (2024). The effect of psychological distance on intertemporal choice of the reward processing: An eye-tracking investigation. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1275484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (1998). The role of feasibility and desirability considerations in near and distant future decisions: A test of temporal construal theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberman, N., & Trope, Y. (2008). The psychology of transcending the here and now. Science, 322(5905), 1201–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, S., Tuladhar, V., Roy, S., Sarmah, P., Rai, K., & Thargay, T. (2022). Do mindsets help in controlling eye gaze? A study to explore the effect of abstract and concrete mindsets on eye movements control. The Journal of General Psychology, 149(2), 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mézière, D. C., Yu, L., Reichle, E. D., Von Der Malsburg, T., & McArthur, G. (2023). Using Eye-Tracking Measures to Predict Reading Comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 58(3), 425–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullen, E., & Monin, B. (2016). Consistency versus licensing effects of past moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 363–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinson, R., Elias, Y., Mentser, S., Bar-Anan, Y., & Gronau, N. (2019). Bi-directional effects of stimulus vertical position and construal level. Social Psychology, 50(3), 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussinson, R., Elias, Y., Yosef-Nitzan, E., Mentser, S., Zadka, M., Weinstein, Z., & Liberman, N. (2021). Vertical position is associated with construal level and psychological distance. Social Cognition, 39(5), 632–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pärnamets, P., Johansson, P., Hall, L., Balkenius, C., Spivey, M. J., & Richardson, D. C. (2015). Biasing moral decisions by exploiting the dynamics of eye gaze. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(13), 4170–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X., Wang, X., & Wu, D. (2019, December 15–18). Displaying “Why” higher than “How”: Display positioning affects construal level. ICIS 2019 Proceedings, Munich, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Rahal, R.-M., & Fiedler, S. (2019). Understanding cognitive and affective mechanisms in social psychology through eye-tracking. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 85, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K. (2009). Eye movements in reading: Models and data. Journal of Eye Movement Research, 2(5), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayner, K., Chace, K. H., Slattery, T. J., & Ashby, J. (2006). Eye movements as reflections of comprehension processes in Reading. Scientific Studies of Reading, 10(3), 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozin, P. (1999). The process of moralization. Psychological Science, 10(3), 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C., Weinmann, M., & Vom Brocke, J. (2018). Digital nudging: Guiding online user choices through interface design. Communications of the ACM, 61(7), 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetlock, P. E., Kristel, O. V., Elson, S. B., Green, M. C., & Lerner, J. S. (2000). The psychology of the unthinkable: Taboo trade-offs, forbidden base rates, and heretical counterfactuals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(5), 853–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110(3), 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Wakslak, C. (2007). Construal levels and psychological distance: Effects on representation, prediction, evaluation, and behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kerckhove, A., Geuens, M., & Vermeir, I. (2015). The floor is nearer than the sky:How looking up or down affects construal level. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1358–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasishth, S., von der Malsburg, T., & Engelmann, F. (2013). What eye movements can tell us about sentence comprehension. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 4(2), 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinmann, M., Schneider, C., & Brocke, J. V. (2016). Digital nudging. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 58, 433–436. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q., Wei, W., Li, N., & Cao, W. (2022). The effects of psychological distance on spontaneous justice inferences: A construal level theory perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1011497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žeželj, I. L., & Jokić, B. R. (2014). Replication of experiments evaluating impact of psychological distance on moral judgment: Replication. Social Psychology, 45(3), 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TP:H | TP:L | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eye-Tracking Indicators | M | SD | M | SD | Welch’s t | Cohen’s d |

| TFD | 1532.48 | 1369.37 | 1843.84 | 1746.42 | 2.78 ** | 0.20 |

| FDP | 0.475 | 0.210 | 0.521 | 0.218 | 2.77 ** | 0.20 |

| FC | 180.84 | 85.39 | 190.74 | 88.47 | 1.73 | |

| FCP | 7.55 | 6.40 | 8.38 | 7.03 | 0.94 | |

| MFD | 0.584 | 0.175 | 0.599 | 0.179 | 3.58 *** | 0.26 |

| FFD | 180.84 | 85.39 | 190.74 | 88.47 | 1.42 | |

| Scenarios | F | p | η2 | TS | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forgot Lunch | 2.42 | 0.13 | 0.03 | H | 5.86 | 2.23 |

| L | 4.67 | 2.44 | ||||

| Choking for Money | 2.17 | 0.15 | 0.04 | H | 2.32 | 1.84 |

| L | 1.67 | 1.37 | ||||

| The Architect | 9.69 ** | 0.003 | 0.19 | H | 4.18 | 1.87 |

| L | 2.54 | 1.56 | ||||

| Standard Trolley | 2.38 | 0.13 | 0.04 | H | 2.46 | 1.99 |

| L | 1.75 | 1.51 | ||||

| Extra Sweater | 16.36 *** | <0.001 | 0.24 | H | 5.14 | 2.05 |

| L | 2.88 | 2.11 | ||||

| Confidential Information | 9.28 ** | 0.004 | 0.18 | H | 4.46 | 1.97 |

| L | 2.71 | 1.81 | ||||

| Donation | 6.88 * | 0.01 | 0.13 | H | 5.32 | 2.21 |

| L | 3.58 | 2.34 | ||||

| Crying Baby | 9.33 ** | 0.004 | 0.18 | H | 5.64 | 2.04 |

| L | 3.75 | 2.11 | ||||

| Vaccine Test | 5.10 * | 0.03 | 0.10 | H | 3.00 | 1.75 |

| L | 2.04 | 1.33 |

| TP:H | TP:L | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | L | H | L | pBonferroni | |

| TFD | 1162 (977) | 1562 (1270) | 1197 (890) | 1420 (1287) | TS: H < L *** |

| FDP | 0.50 (0.25) | 0.59 (0.23) | 0.50 (0.24) | 0.57 (0.24) | TS: H < L *** |

| FC | 5.62 (4.19) | 7.10 (5.60) | 5.65 (4.09) | 6.29 (5.21) | TS: H < L * |

| FCP | 0.59 (0.20) | 0.66 (0.18) | 0.59 (0.20) | 0.64 (0.19) | TS: H < L *** |

| MFD | 204 (72) | 226 (73) | 222 (96) | 225 (88) | TS: H < L * |

| FFD | 197 (105) | 197 (99) | 191 (74) | 197 (81) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, Q.; Bai, X. The Influence of Spatial Distance and Trade-Off Salience on Ethical Decision-Making: An Eye-Tracking Study Based on Embodied Cognition. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070911

Yang Y, Li Y, Lin Q, Bai X. The Influence of Spatial Distance and Trade-Off Salience on Ethical Decision-Making: An Eye-Tracking Study Based on Embodied Cognition. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):911. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070911

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Yu, Yirui Li, Qingsong Lin, and Xuejun Bai. 2025. "The Influence of Spatial Distance and Trade-Off Salience on Ethical Decision-Making: An Eye-Tracking Study Based on Embodied Cognition" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070911

APA StyleYang, Y., Li, Y., Lin, Q., & Bai, X. (2025). The Influence of Spatial Distance and Trade-Off Salience on Ethical Decision-Making: An Eye-Tracking Study Based on Embodied Cognition. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 911. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070911