Family Resilience, Support, and Functionality in Breast Cancer Patients: A Longitudinal Pre- and Post-Operative Study

Abstract

1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sample Collection

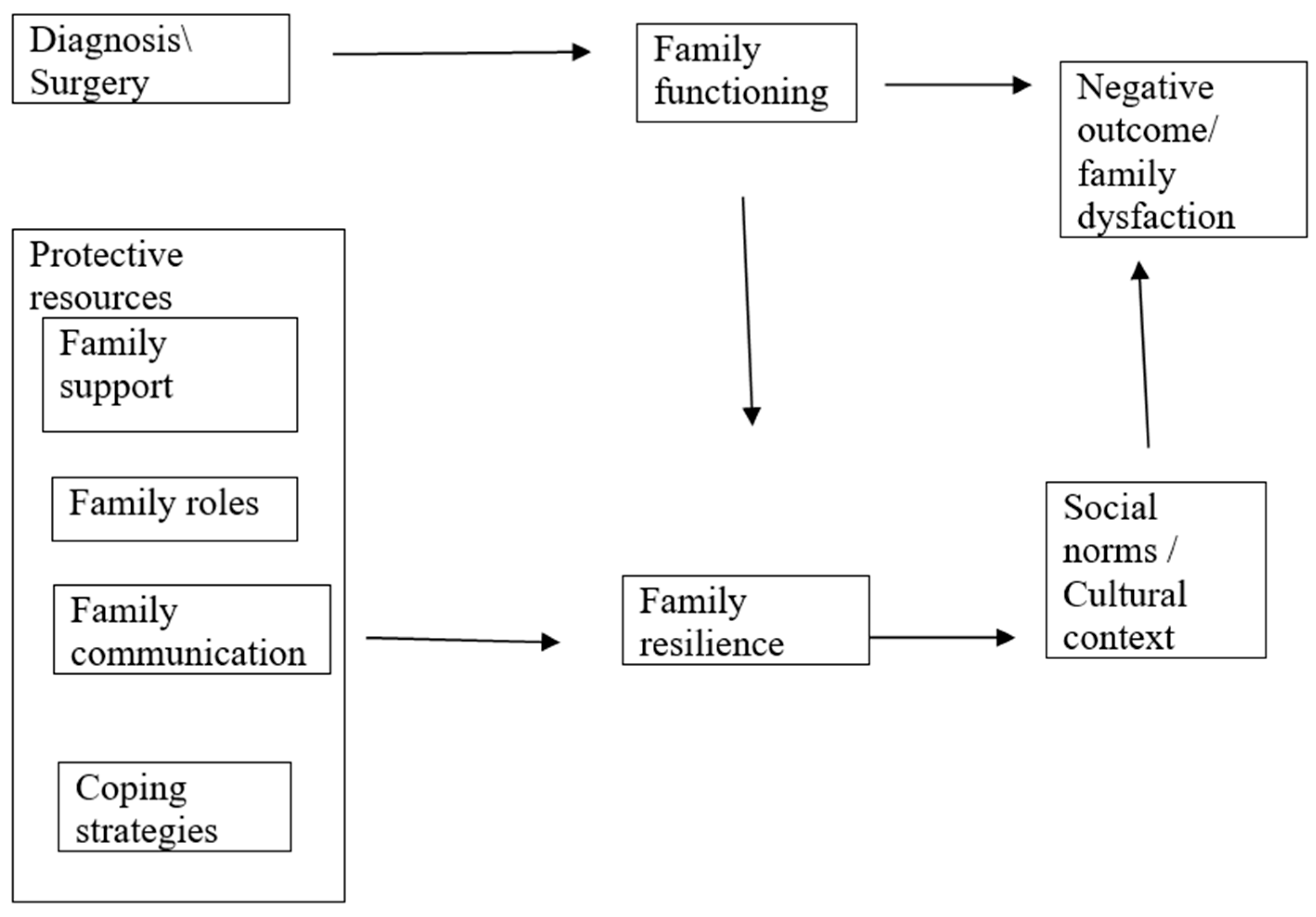

- Stressful event: the diagnosis of breast cancer in combination with surgery.

- Family resources: communication, support, and roles.

- Family perceptions: the interpretation of stress and meaning-making strategies.

- Resilience/adaptation: the outcome of the process.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Characteristics

2.2.2. Family Assessment Device (FAD)

2.2.3. Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scales (F-COPES)

2.2.4. Family Problem Solving Communication (FPSC)

2.2.5. Family Support Scale (FS13)

2.3. Participants

- Patients with a recent breast cancer diagnosis

- Age over 18 years old

- Be able to respond to the research tool by digital means

- Patients were admitted to hospital and underwent mastectomy

- Informed consent for participation

- Being fluent in Greek

- Being literate

2.4. Ethics

3. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

4.2. Measurements and Changes in Scales After Surgery

4.3. Changes in Scales According to the Type of Treatment

4.4. Correlations Between Scale Changes

5. Discussion

5.1. Cultural Context of the Greek Family

5.2. Original Contribution and Research Gap

5.3. Clinical Implications

- The establishment of specialized psycho-oncology centers in public hospitals, which would provide systematic monitoring of psychosocial needs and would provide targeted support during critical phases of treatment for patients and their families.

- Utilization of digital health infrastructure for psychosocial interventions through digital media, especially in remote areas.

- Empowerment of both patients and their families. Strengthening family resilience, social support, and family support in patients at increased risk.

- Training health professionals in the recognition and management of the psychosocial dimension of cancer, based on the findings of the study.

5.4. Generalizability of the Findings

5.5. Limitations and Strengths of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acquati, C., Miyawaki, C. E., & Lu, Q. (2020). Post-traumatic stress symptoms and social constraints in the communication with family caregivers among Chinese-speaking breast cancer survivors. Supportive Care in Cancer, 28, 4115–4122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altun, H., Kurtul, N., Arici, A., & Yazar, E. M. (2019). Evaluation of emotional and behavioral problems in school-age children of patients with breast cancer. Turkish Journal of Oncology, 34, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriopoulou, M., Charos, D., & Stergiadi, E. (2018). The impact of cancer on patients and their caregivers, and the importance of empowerment. Archives of Hellenic Medicine, 35, 601–611. Available online: https://www.mednet.gr/archives/2018-5/601abs.html (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Bultmann, J. C., Beierlein, V., Romer, G., Moller, B., Koch, U., & Bergel, C. (2014). Parental cancer: Health-related quality of life and current psychosocial support needs of cancer survivors and their children. International Journal of Cancer, 135, 2668–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charalambous, A., Kaite, C. P., Charalambous, M., Tistsi, T., & Kouta, C. (2017). The effects on anxiety and quality of life of breast cancer patients following completion of the first cycle of chemotherapy. SAGE Open Medicine, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charos, D., Andriopoulou, M., Lykeridou, K., Deltsidou, A., Kolokotroni, P., & Vivilaki, V. (2023). Psychological effects of breast cancer in women and their families: A systematic review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 18(2), 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charos, D., Merluzzi, T. V., Kolokotroni, P., Lykeridou, K., Deltsidou, A., & Vivilaki, V. (2021). Breast cancer and social relationship coping efficacy: Validation of the Greek version. Women & Health, 61(10), 947–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Wang, Q. J., Li, H. P., Zhang, T., Zhang, S., & Zhou, M. K. (2021). Family resilience, perceived social support, and individual resilience in cancer couples: Analysis using the actor-partner interdependence mediation model. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 52, 101932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coyne, E., Wollin, J., & Creedy, D. K. (2012). Exploration of the family’s role and strengths after a young woman is diagnosed with breast cancer: Views of women and their families. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., & Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster family assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EU General Data Protection Regulation. (2016). European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of Such Data (General Data Protection Regulation); OJ L 119, 4.5.2016, pp. 1–88.

- Faccio, F., Gandini, S., Renzi, C., Fioretti, C., Crico, C., & Pravettoni, G. (2019). Development and validation of the Family Resilience (FaRE) Questionnaire: An observational study in Italy. BMJ Open, 9, e024670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fradelos, E. C., Latsou, D., Mitsi, D., Tsaras, K., Lekka, D., Lavdaniti, M., Tzavella, F., & Papathanasiou, I. V. (2018). Assessment of the relation between religiosity, mental health, and psychological resilience in breast cancer patients. Contemporary Oncology (Pozn), 22(3), 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouva, M., Dragioti, E., Konstanti, Z., Kotrotsiou, E., & Koulouras, V. (2016). Translation and validation of a Greek version of the family crisis oriented personal evaluation scales (F-COPES). Interscientific Health Care, 2, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hammersen, F., Pursche, T., Fischer, D., Katalinic, A., & Waldmann, A. (2021). Psychosocial and family-centered support among breast cancer patients with dependent children. Psycho-Oncology, 30(3), 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, K., Becker, K., & Mattejat, F. (2013). Impact of family-oriented rehabilitation and prevention: An inpatient program for mothers with breast cancer and their children. Psycho-Oncology, 22(12), 2684–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julkunen, J., & Greenglass, E. R. (1989). Family support measure. Unpublished manuscript.

- Kalogeraki, S. (2009). The impact of culture on family support for elderly people in Greece. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 40(4), 617–632. [Google Scholar]

- Kovac, A., Petrović, S. P., Nedeljković, M., Kojić, M., & Tomić, S. (2014). Post-operative condition of breast cancer patients from standpoint of psycho-oncology—Preliminary results. Medical Pregled, 67(1–2), 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K. W. S., Qiao, Y., Luan, X., Li, Y., & Wang, K. (2019). Family resilience and psychological wellbeing among Chinese breast cancer survivors and their caregivers. European Journal of Cancer Care, 28(1), e12984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Wang, K., Yin, Y., Li, Y., & Li, S. (2018). Relationships between family resilience, breast cancer survivors’ individual resilience, and caregiver burden: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 88, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B., Wu, X., Shi, L., Li, H., Wu, D., Lai, X., Li, Y., Yang, Y., & Li, D. (2021). Correlations of social isolation and anxiety and depression symptoms among patients with breast cancer of Heilongjiang province in China: The mediating role of social support. Nursing Open, 8, 1981–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Li, Y., Chen, L., Qi, W., & Yu, L. (2018). Relationships between family resilience and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors and caregiver burden. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCubbin, H. I., & Patterson, J. M. (1983). The family stress process: The double ABCX model of adjustment and adaptation. In H. I. McCubbin, M. B. Sussman, & J. M. Patterson (Eds.), Social stress and the family: Advances and developments in family stress theory and research (pp. 7–37). Haworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin, H. I., Olson, D., & Larsen, A. (1996a). Family crisis oriented personal evaluation scales, 1981. In H. I. McCubbin, A. I. Thompson, & M. A. McCubbin (Eds.), Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation: Inventories for research and practice (pp. 455–508). University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin, H. I., Thompson, A. I., & McCubbin, M. A. (1996b). Family problem-solving communication (FPSC). In Family assessment: Resiliency, coping and adaptation, inventories for research and practice (pp. 639–684). University of Wisconsin Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin, H. I., Thompson, A. I., & McCubbin, M. A. (2001). Family problem-solving communication index (FPSC). In J. Fischer, & K. J. Corcoran (Eds.), Measures for clinical practice and research: A sourcebook (Vol. 1, pp. 314–315). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi, T. V., Philip, E. J., Yang, M., & Heitzmann, C. A. (2016). Matching of received social support with need for support in adjusting to cancer and cancer survivorship. Psychooncology, 25, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshtagh, M., & Allahyari, E. (2022). Informational and supportive needs of the family caregivers of women with breast cancer in a low-resource context: A cross-sectional study. Palliative Medicine in Practice, 16(1), 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidoo, N., & Greeff, A. P. (2022). Resilience in low- to middle-income families with a mother diagnosed with breast cancer. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 52(1), 128–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, Y., Iwamitsu, Y., Kuranami, M., Okazaki, S., Yamamoto, K., Watanabe, M., & Miyaoka, H. (2013). Predictors of psychological distress in breast cancer patients after surgery. Kitasato Medical Journal, 43, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, G. H., Yeom, C. W., Shim, E. J., Jung, D., Lee, K. M., Son, K. L., Kim, W. H., Moon, J. Y., Jung, S., Kim, T. Y., AhIm, S., Lee, K. H., & Hahm, N. J. (2020). The effect of perceived social support on chemotherapy-related symptoms in patients with breast cancer: A prospective observational study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 130, 109911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleife, H., Sachtleben, C., Barboza, F., Singer, S., & Hinz, A. (2012). Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in German ambulatory breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer, 21, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C., & Badger, T. A. (2010). Interdependence in Latina breast cancer patients. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrin, C., Badger, T. A., Sikorskii, A., Crane, T. E., & Thaddeus, W. W. (2018). A dyadic analysis of stress processes in Latinas with breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 838–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, K., Zografos, E., Zografos, G. C., Vaslamatzis, G., Zografos, C. G., & Kolaitis, G. (2020). Emotional and behavioral problems in children dealing with maternal breast cancer: A literature review. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 48, 394–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. S., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, R., Brandão, T., & Matos, P. M. (2018). Mothers with breast cancer: A mixed-method systematic review on the impact on the parent-child relationship. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsamparli, A., Petmeza, I., McCarthy, G., & Adamis, D. (2018). The Greek version of the McMaster family assessment device. PsyChJournal, 7(3), 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselebis, A., Anagnostopoulou, T., Bratis, D., Moulou, A., Maria, A., Sikaras, C., Ilias, I., Karkanias, I. A., Moussas, G., & Tzanakis, N. (2011). The 13-item family support scale: Reliability and validity of the Greek translation in a sample of Greek health care professionals. Asia Pacific Family Medicine, 10(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, F. (2004). A family resilience framework: Innovative practice applications. Family Relations, 51, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Wang, X., Chen, M., Shi, Y., & Hu, Y. (2021). Family interaction among young Chinese breast cancer survivors. BMC Family Practice, 22, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, W., Shah, D. V., Shaw, B. R., Kim, E., Smaglik, P., Roberts, J., Hawkins, R. P., Pingree, S., McDowell, H., & Gustafson, D. H. (2014). The role of the family environment and computer-mediated social support on breast cancer patients’ coping strategies. Journal of Health Communication, 19(9), 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N | M/ Percentage % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52.1 (10.3) | ||

| Educational level | |||

| Primary school | 2 | 3.4 | |

| Middle school | 5 | 8.6 | |

| High school | 14 | 24.1 | |

| Post-secondary education | 7 | 12.1 | |

| Higher education | 19 | 32.8 | |

| Postgraduate education | 7 | 12.1 | |

| PhD | 4 | 6.9 | |

| Employment Status | |||

| Unemployed | 5 | 8.8 | |

| Private employee | 12 | 21.1 | |

| Civil servant | 17 | 29.8 | |

| Housekeeping | 9 | 15.8 | |

| Entrepreneur | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Freelancer | 3 | 5.3 | |

| Other | 10 | 17.5 | |

| Area of residence | |||

| <2000 inhabitants | 4 | 6.9 | |

| 2000–10,000 inhabitants | 7 | 12.1 | |

| 10,000–100,000 inhabitants | 12 | 20.7 | |

| >100,000 inhabitants | 35 | 60.3 | |

| Nationality | |||

| Greek | 57 | 98.3 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Unmarried | 6 | 10.5 | |

| Partnership | 1 | 1.8 | |

| Married | 38 | 66.7 | |

| Divorced | 7 | 12.3 | |

| Separated | 2 | 3.5 | |

| Widowed | 3 | 5.3 | |

| Mothers | |||

| No | 10 | 17.2 | |

| Yes | 48 | 82.8 | |

| Children’s gender | |||

| Male | 15 | 3.6 | |

| Female | 17 | 37 | |

| Male and Female | 14 | 30.4 | |

| Number of participants who had underage children | 20 | 34.4 | |

| Monthly income | |||

| Up to EUR 1000 | 30 | 55.6 | |

| EUR 1001–1500 | 10 | 18.5 | |

| EUR 1501–2000 | 10 | 18.5 | |

| EUR 2001 and over | 4 | 7.4 | |

| Family history of cancer | |||

| No | 26 | 44.8 | |

| Yes | 32 | 55.2 | |

| Member of family with cancer diagnosis | |||

| Mother | 6 | 19.4 | |

| Father | 7 | 22.6 | |

| Siblings | 5 | 16.1 | |

| Grandparents | 9 | 29 | |

| Uncle/aunt | 4 | 6.9 | |

| Person first informed of their cancer | |||

| Husband/Partner | 33 | 56.9 | |

| Father | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Mother | 5 | 8.6 | |

| Children | 7 | 12.1 | |

| Friends | 6 | 10.3 | |

| No one | 2 | 3.4 | |

| Other | 3 | 5.2 | |

| Many family members | 2 | 3.4 | |

| Person closest to the patient | |||

| Husband/Partner | 30 | 51.7 | |

| Father | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Mother | 4 | 6.9 | |

| Children | 14 | 24.1 | |

| Friends | 1 | 1.7 | |

| No one | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Other | 1 | 1.7 | |

| Many family members | 7 | 12.1 | |

| N | Pre-Surgery | Post-Surgery | Change | Paired t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Problem solving (FAD) | 47 | 1.83 (0.39) | 1.96 (0.46) | 0.13 (0.44) | 0.048 |

| Communication (FAD) | 46 | 1.92 (0.51) | 1.97 (0.58) | 0.05 (0.59) | 0.599 |

| Roles (FAD) | 47 | 2.18 (0.45) | 2.14 (0.41) | −0.04 (0.55) | 0.632 |

| Affective responses (FAD) | 50 | 1.84 (0.52) | 1.84 (0.7) | −0.1 (0.66) | 0.944 |

| Affective involvement (FAD) | 48 | 1.95 (0.42) | 2 (0.49) | 0.05 (0.43) | 0.450 |

| Behavior control (FAD) | 41 | 2.37 (0.39) | 2.28 (0.37) | −0.09 (0.49) | 0.262 |

| General functioning (FAD) | 45 | 1.76 (0.43) | 1.79 (0.54) | 0.03 (0.5) | 0.694 |

| Acquiring Social Support (F-COPES) | 52 | 28.2 (6.4) | 27 (7.7) | −1.1 (6.8) | 0.240 |

| Reframing (F-COPES) | 49 | 33 (4.5) | 32.7 (4.6) | −0.3 (3.9) | 0.636 |

| Seeking Spiritual Support (F-COPES) | 57 | 12.6 (4.9) | 13 (4.9) | 0.4 (3.7) | 0.482 |

| Mobilizing Family to Acquire and Accept Help (F-COPES) | 58 | 15 (3.8) | 14.5 (3.7) | −0.5 (3.7) | 0.321 |

| Passive Appraisal (F-COPES) | 56 | 12.3 (3.7) | 12 (3.5) | −0.3 (3.1) | 0.439 |

| Overall F-COPES | 44 | 102.8 (14.1) | 101.6 (15.3) | −1.3 (13.1) | 0.523 |

| Family Problem Solving Communication (FPSC) | 55 | 20.3 (4.1) | 19.3 (4.4) | −1 (4.2) | 0.097 |

| Family support (FS-13) | 47 | 63 (7.7) | 51 (8) | −12 (6.9) | <0.001 |

| Type of Treatment | Pre-Surgery | Post-Surgery | Change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | P 2 | P 3 | ||

| Acquiring Social Support | Chemotherapy | 28 (5.8) | 25.1 (6.2) | −2.9 (5.6) | 0.030 | 0.173 |

| Radiotherapy | 29.3 (9.4) | 27.4 (8.7) | −1.9 (3.2) | 0.174 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 27.4 (4.6) | 31 (6.4) | 3.6 (10) | 0.339 | ||

| None | 27.4 (4.9) | 26.7 (8.9) | −0.6 (8.2) | 0.802 | ||

| P 1 | 0.915 | 0.317 | ||||

| Reframing | Chemotherapy | 32.1 (4.7) | 31.5 (4.3) | −0.6 (3.6) | 0.410 | 0.536 |

| Radiotherapy | 35.5 (2.5) | 34.3 (4.1) | −1.2 (3.3) | 0.428 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 31.5 (4.6) | 33.2 (6) | 1.7 (7.6) | 0.615 | ||

| None | 35.3 (3.2) | 34.2 (4.2) | −1.1 (2) | 0.104 | ||

| P 1 | 0.038 | 0.162 | ||||

| Seeking Spiritual Support | Chemotherapy | 12.2 (5.2) | 11.8 (4.9) | −0.5 (2.4) | 0.369 | 0.122 |

| Radiotherapy | 14.1 (6.7) | 12.7 (6.4) | −1.4 (1.4) | 0.035 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 13.3 (4.7) | 16 (3.5) | 2.8 (6.2) | 0.249 | ||

| None | 12.4 (4.6) | 13.2 (5) | 0.8 (4.6) | 0.558 | ||

| P 1 | 0.828 | 0.229 | ||||

| Mobilizing Family to Acquire and Accept Help | Chemotherapy | 14.6 (3.5) | 13 (4) | −1.6 (3.6) | 0.043 | 0.188 |

| Radiotherapy | 16.3 (2.5) | 16 (1.9) | −0.3 (1.4) | 0.626 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 16.3 (3.7) | 16.8 (2.4) | 0.5 (4.1) | 0.743 | ||

| None | 14.5 (4.5) | 15.4 (3.7) | 0.8 (3.6) | 0.416 | ||

| P 1 | 0.507 | 0.029 | ||||

| Passive Appraisal | Chemotherapy | 12.3 (3.3) | 12.7 (3.4) | 0.3 (3.5) | 0.637 | 0.338 |

| Radiotherapy | 12.9 (4.9) | 12.4 (3.5) | −0.5 (2.5) | 0.590 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 12.5 (3) | 10.5 (3.3) | −2 (2.9) | 0.090 | ||

| None | 12.7 (3) | 12 (3.4) | −0.7 (3) | 0.452 | ||

| P 1 | 0.979 | 0.457 | ||||

| Overall F-COPES | Chemotherapy | 100.1 (10.9) | 95.3 (13.5) | −4.8 (11.3) | 0.079 | 0.167 |

| Radiotherapy | 112.4 (17.4) | 107.6 (18.3) | −4.8 (7.9) | 0.248 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 103.8 (16.2) | 112.7 (10.5) | 8.8 (21) | 0.349 | ||

| None | 106.2 (13.4) | 105.7 (15.6) | −0.5 (12.5) | 0.902 | ||

| P 1 | 0.236 | 0.045 |

| Type of Treatment | Pre-Surgery | Post-Surgery | Change | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | P 2 | P 3 | ||

| FS-13 | Chemotherapy | 65.3 (6.3) | 52 (6.9) | −13.3 (6.6) | <0.001 | 0.458 |

| Radiotherapy | 66.7 (7.9) | 52.7 (8.4) | −14 (4.2) | <0.001 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 59.6 (9.2) | 48.4 (8.2) | −11.1 (8.5) | 0.013 | ||

| None | 61.7 (7.4) | 52.2 (8.8) | −9.5 (8.1) | 0.002 | ||

| P 1 | 0.172 | 0.698 | ||||

| FPSC | Chemotherapy | 19.1 (4.4) | 18.6 (4.2) | −0.5 (3.4) | 0.479 | 0.976 |

| Radiotherapy | 20.9 (3.2) | 20.8 (3) | −0.1 (3.8) | 0.928 | ||

| Hormone therapy | 21.3 (4.2) | 20.9 (5) | −0.4 (3.8) | 0.774 | ||

| None | 21.2 (2.8) | 20.4 (2.8) | −0.8 (2.3) | 0.260 | ||

| P 1 | 0.298 | 0.354 |

| F-COPES: Pre-Post Comparison | FS-13 | FPSC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acquiring Social Support | R | 0.55 | −0.42 |

| P | 0.064 | 0.177 | |

| Reframing | R | 0.80 | −0.14 |

| P | 0.002 | 0.659 | |

| Seeking Spiritual Support | R | 0.28 | −0.44 |

| P | 0.371 | 0.150 | |

| Mobilizing Family to Acquire and Accept Help | R | 0.17 | −0.29 |

| P | 0.604 | 0.353 | |

| Passive Appraisal | R | −0.10 | 0.19 |

| P | 0.755 | 0.555 | |

| Overall F-COPES | R | 0.63 | −0.45 |

| P | 0.027 | 0.143 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Charos, D.; Andriopoulou, M.; Kyrkou, G.; Kolliopoulou, M.; Deltsidou, A.; Bothou, A.; Vivilaki, V. Family Resilience, Support, and Functionality in Breast Cancer Patients: A Longitudinal Pre- and Post-Operative Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070880

Charos D, Andriopoulou M, Kyrkou G, Kolliopoulou M, Deltsidou A, Bothou A, Vivilaki V. Family Resilience, Support, and Functionality in Breast Cancer Patients: A Longitudinal Pre- and Post-Operative Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):880. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070880

Chicago/Turabian StyleCharos, Dimitrios, Maria Andriopoulou, Giannoula Kyrkou, Maria Kolliopoulou, Anna Deltsidou, Anastasia Bothou, and Victoria Vivilaki. 2025. "Family Resilience, Support, and Functionality in Breast Cancer Patients: A Longitudinal Pre- and Post-Operative Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070880

APA StyleCharos, D., Andriopoulou, M., Kyrkou, G., Kolliopoulou, M., Deltsidou, A., Bothou, A., & Vivilaki, V. (2025). Family Resilience, Support, and Functionality in Breast Cancer Patients: A Longitudinal Pre- and Post-Operative Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 880. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070880