The Impact of Childhood Abuse on the Development of Early Maladaptive Schemas and the Expression of Violence in Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Current Study

- Is there an association between previous experiences of direct victimization in the family and the level of violence in school or outside school during adolescence?

- Do maladaptive schemas, as proposed by schema therapy, mediate the relationship between adolescents’ previous experiences of direct familial victimization and their involvement in violent behavior in school or outside of school?

2. Methods

2.1. Assessment Instruments

2.2. Participants

3. Results

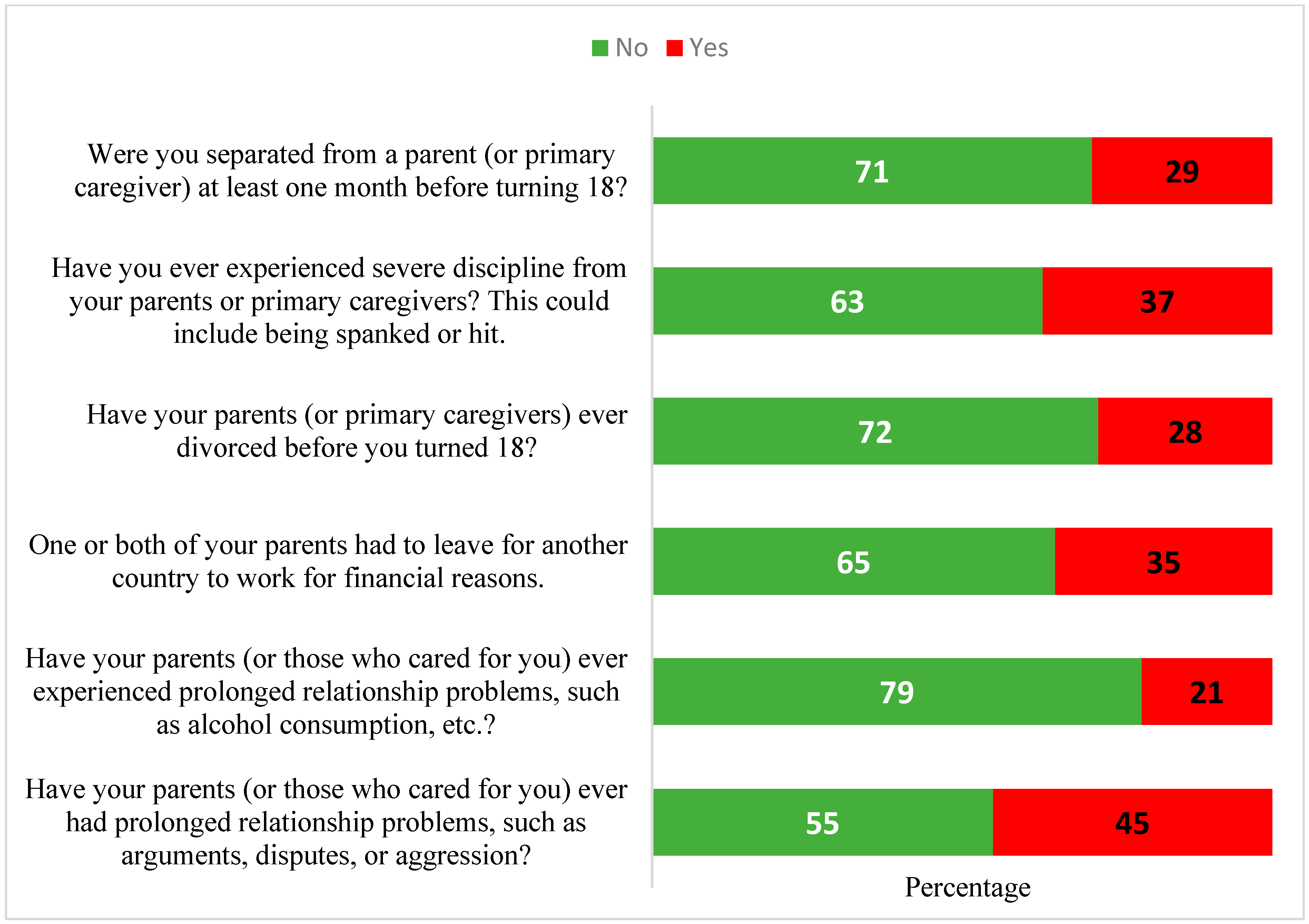

3.1. Descriptive Data

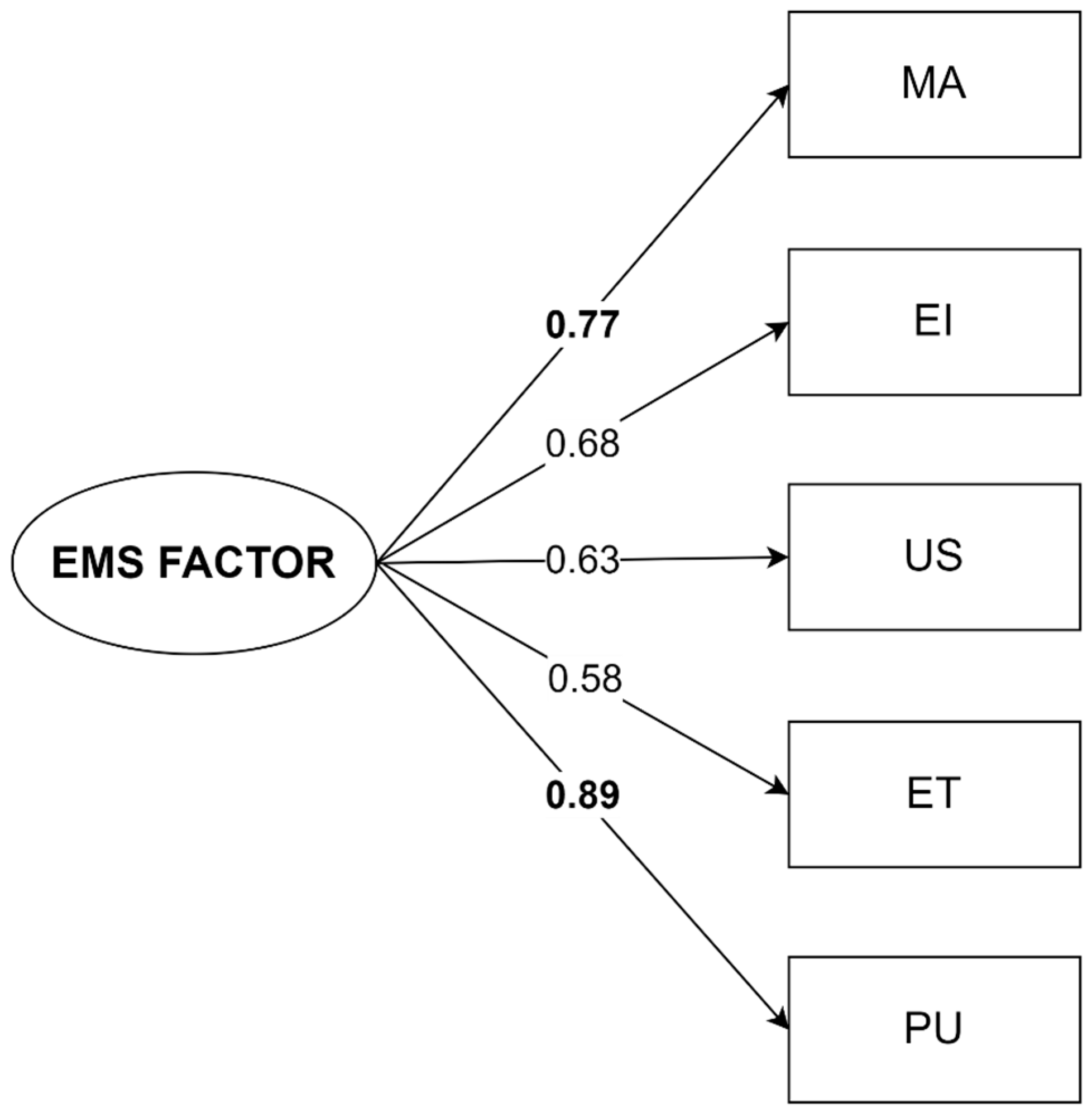

3.2. Unifactorial Model

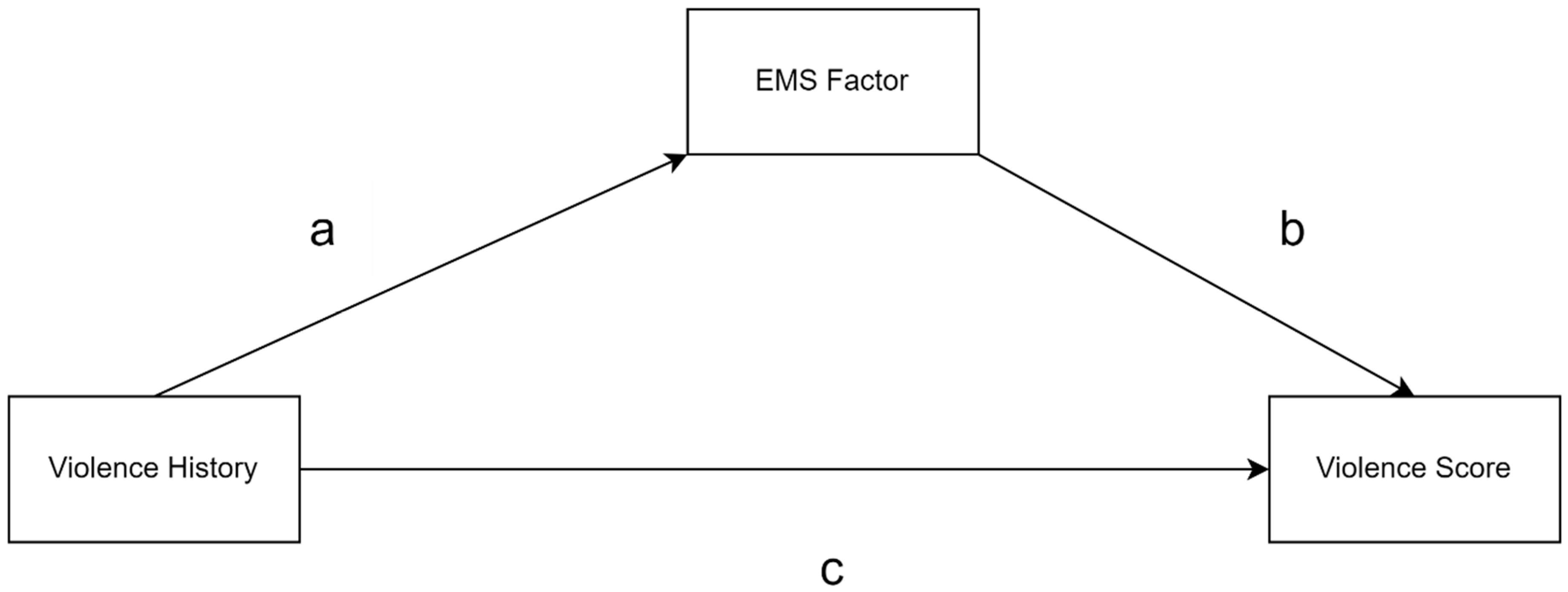

3.3. Mediation Model

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aalbers, G., Engels, T., Haslbeck, J. M., Borsboom, D., & Arntz, A. (2021). The network structure of schema modes. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(5), 1065–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, R. L., & Sellers, C. S. (2009). Criminological theories: Introduction, evaluation, and application (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Albu, M. (Coord.). (2008). Un nou chestionar de personalitate: CP5F [A new personality questionnaire: CP5F]. In Incursiuni psihologice în cotidian [Psychological incursions into everyday life] (pp. 7–23). Editura ASCR [ASCR Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Arshad, L. (2024). A correlational study of emotional deprivation and bullying victimization in adolescence with single parent. Clinical Case Reports and Studies, 6(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, S., & Gençöz, T. (2016). Exploring revictimization process among Turkish women: The role of early maladaptive schemas on the link between child abuse and partner violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bär, A., Bär, H. E., Rijkeboer, M. M., & Lobbestael, J. (2023). Early maladaptive schemas and schema modes in clinical disorders: A systematic review. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 96(3), 716–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A. T. (1979). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Benedini, K. M., Fagan, A. A., & Gibson, C. L. (2016). The cycle of victimization: The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent peer victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 59, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlin, L. J., Appleyard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blankenstein, N. E., Vandenbroucke, A. R., de Vries, R., Swaab, H., Popma, A., & Jansen, L. (2022). Understanding aggression in adolescence by studying the neurobiological stress system: A systematic review. Motivation Science, 8(2), 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J. L., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2020). Early maladaptive schemas as mediators between child maltreatment and dating violence in adolescence. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 25, 3119–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Volume II: Separation, anxiety and anger. The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Budău, O., & Albu, M. (2010). SACS Scala de abordare strategică a copingului [SACS strategic approach coping scale]. Editura ASCR [ASCR Publishing House]. [Google Scholar]

- Calvete, E. (2014). Emotional abuse as a predictor of early maladaptive schemas in adolescents: Contributions to the development of depressive and social anxiety symptoms. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(4), 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Cortazar, N., & Orue, I. (2025). Moderating and mediating mechanisms of the association between endogenous testosterone and aggression in youth: A study protocol. PLoS ONE, 20(2), e0319426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Estévez, A., López de Arroyabe, E., & Ruiz, P. (2005). The schema questionnaire-short form. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(2), 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Fernández-González, L., González-Cabrera, J. M., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2018a). Continued bullying victimization in adolescents: Maladaptive schemas as a mediational mechanism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., Fernández-González, L., Orue, I., & Little, T. D. (2018b). Exposure to family violence and dating violence perpetration in adolescents: Potential cognitive and emotional mechanisms. Psychology of Violence, 8(1), 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., & Orue, I. (2010). Cognitive schemas and aggressive behavior in adolescents: The mediating role of social information processing. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 13(1), 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, E., & Orue, I. (2012). Social information processing as a mediator between cognitive schemas and aggressive behavior in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(1), 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., Gamez-Guadix, M., & Bushman, B. J. (2015). Predictors of child-to-parent aggression: A 3-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsi, L., Paleari, F. G., & Fincham, F. D. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and early maladaptive schemas as predictors of cyber dating abuse: An actor-partner interdependence mediation model approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 623646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurbea, F.-E., Marinescu, V., Rodideal, A.-A., Neagu, A.-E., & Rada, C. (2025). Adolescents and violence: A systematic review of protective and risk factors. Anthropological Researches and Studies, 15, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, E., & Wright, M. O. D. (2007). The impact of childhood psychological maltreatment on interpersonal schemas and subsequent experiences of relationship aggression. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 7(2), 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, E., & Çalık, M. (2022). Examining the relationship between sensation seeking, positive and negative experiences, emotional autonomy and coping strategies in adolescents. International Journal of Educational Psychology: IJEP, 11(1), 68–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. C., Masters, N. T., Casey, E., Kajumulo, K. F., Norris, J., & George, W. H. (2018). How childhood maltreatment profiles of male victims predict adult perpetration and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(6), 915–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiStefano, C., Zhu, M., & Mindrila, D. (2009). Understanding and using factor scores: Considerations for the applied researcher. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 14(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (1990). Mechanisms in the cycle of violence. Science, 250, 1678–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, N. N., Pettingell, S. L., McMorris, B. J., & Borowsky, I. W. (2010). Adolescent violence perpetration: Associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 125(4), e778–e786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, A. L., Gilbert, F., Lee, S., & Daffern, M. (2018). The role of aggression-related early maladaptive schemas and schema modes in aggression in a prisoner sample. Aggressive Behavior, 44(3), 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, D. J. A. (2022). Using schema modes for case conceptualization in schema therapy: An applied clinical approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 763670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, M. P., & Malti, T. (2015). Aggressive and violent behavior. In Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Socioemotional processes (Vol. 3, pp. 794–841). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, M., Moghadasin, M., Mastour, H., & Tayebi, A. (2024). Early maladaptive schema, attachment style, and parenting style in a clinical population with personality disorder and normal individuals: A discriminant analysis model. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission: Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture. (2021). Education and training monitor 2021: Romania. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-González, L., Orue, I., Adrián, L., & Calvete, E. (2022). Child-to-parent aggression and dating violence: Longitudinal associations and the predictive role of early maladaptive schemas. Journal of Family Violence, 37(1), 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, E. E., Ryan, N. D., Phillips, M. L., Manuck, S. B., Worthman, C. M., Moyles, D. L., Tarr, J. A., Sciarrillo, S. R., & Dahl, R. E. (2010). Healthy adolescents’ neural response to reward: Associations with puberty, positive affect, and depressive symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(2), 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido, E. F., Weiler, L. M., & Taussig, H. N. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences and health-risk behaviors in vulnerable early adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(5), 661–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, F., Daffern, M., Talevski, D., & Ogloff, J. R. (2013). The role of aggression-related cognition in the aggressive behavior of offenders: A general aggression model perspective. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(2), 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J., & Chan, R. C. (2018). Early maladaptive schemas as mediators between childhood maltreatment and later psychological distress among Chinese college students. Psychiatry Research, 259, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi, T. (1990). A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gubbels, J., Assink, M., & van der Put, C. E. (2024). Protective factors for antisocial behavior in youth: What is the meta-analytic evidence? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(2), 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunty, B., & Buri, Z. (2008, May 4). Parental practices and the development of maladaptive schemas [Paper presentation]. Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt, J. (2024). The anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Hassija, C. M., Robinson, D., Silva, Y., & Lewin, M. R. (2018). Dysfunctional parenting and intimate partner violence perpetration and victimization among college women: The mediating role of schemas. Journal of Family Violence, 33, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A., Barter, C., Szilassy, E., Heron, J., Fraser, A., Barnes, M., Yakubovich, A. R., Feder, G., & Howe, L. D. (2025). The impact of parental intimate partner violence and abuse (IPVA) on young adult relationships: A UK general population cohort study. The Lancet Regional Health–Europe, 53, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrenkohl, T. I., & Rousson, A. N. (2018). IPV and the intergenerational transmission of violence. Family & Intimate Partner Violence Quarterly, 10(4), 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, J. A., McAuliffe, M. D., Morrow, M. T., & Romano, L. J. (2010). Reactive and proactive aggression in childhood and adolescence: Precursors, outcomes, processes, experiences, and measurement. Journal of Personality, 78(1), 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. (2020). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp.

- Ibrahim, A. M., Zaghamir, D. E. F., Alradaydeh, M. F., & Elsehrawy, M. G. (2024). Factors influencing aggressive behavior as perceived by university students. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences, 20, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovsky, T., Rock, A. J., Thorsteinsson, E. B., Clark, G. I., & Murray, C. V. (2020). The relationship between early maladaptive schemas and interpersonal problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 27(3), 408–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JASP Team. (2024). JASP (Version 0.19.3) [Computer software]. JASP Team.

- Jennings, W. G., Park, M., Richards, T. N., Tomsich, E., Gover, A., & Powers, R. A. (2014). Exploring the relationship between child physical abuse and adult dating violence using a causal inference approach in an emerging adult population in South Korea. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(12), 1902–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karantzas, G. C., Younan, R., & Pilkington, P. D. (2023). The associations between early maladaptive schemas and adult attachment styles: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 30(1), 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaukinen, C., Buchanan, L., & Gover, A. R. (2015). Child abuse and the experience of violence in college dating relationships: Examining the moderating effect of gender and race. Journal of Family Violence, 30, 1079–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keels, M. (2022). Developmental & ecological perspective on the intergenerational transmission of trauma & violence. Daedalus, 151(1), 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M., & Fernàndez-Castillo, N. (2021). Editorial: In search of mechanisms: Genes, brains, and environment in aggressive behavior. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 643747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, J., Lee, H., Slack, K. S., & Lee, E. (2021). The moderating role of three-generation households in the intergenerational trans-mission of violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M. R., Halász, J., Meelis, W., & Haller, J. (2004). Fast positive feedback between the adrenocortical stress response and a brain mechanism involved in aggressive behavior. Behavioral Neuroscience, 118(5), 1062–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansford, J. E., Criss, M. M., Laird, R. D., Shaw, D. S., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 23(1), 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, T. (2022). Family violence, depressive symptoms, school bonding, and bullying perpetration: An intergenerational transmission of violence perspective. Journal of School Violence, 21(4), 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lösel, F., & Bender, D. (2017). Protective factors against crime and violence in adolescence. In The Wiley handbook of violence and aggression (pp. 1–15). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martoccio, T. L., Berlin, L. J., Aparicio, E. M., Appleyard Carmody, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2022). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Explicating underlying mechanisms. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(1–2), 973–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, T., Younan, R., & Pilkington, P. D. (2022). Adolescent maladaptive schemas and childhood abuse and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(4), 1159–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAra, L., & McVie, S. (2016). Understanding youth violence: The mediating effects of gender, poverty and vulnerability. Journal of Criminal Justice, 45, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M. C., & Lumley, M. N. (2012). Sources of emotional maltreatment and the differential development of unconditional and conditional schemas. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41(4), 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, M., Roring, S., Winterowd, C., & Porras, C. (2012). The relationship of negative self-schemas and insecure partner attachment styles with anger experience and expression among male batterers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(13), 2685–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, M. T., Ford, D. C., Ports, K. A., & Guinn, A. S. (2018). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences from the 2011–2014 behavioral risk factor surveillance system in 23 states. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(11), 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milaniak, I., & Widom, C. S. (2015). Does child abuse and neglect increase risk for perpetration of violence inside and outside the home? Psychology of Violence, 5(3), 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muris, P. (2006). Maladaptive schemas in non-clinical adolescents: Relations to perceived parental rearing behaviours, big five personality factors and psychopathological symptoms. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organizația Salvați Copiii [Save the Children Organisation]. (2021). Studiu privind incidența violenței asupra copiilor [Study on the incidence of violence against children]. Salvați Copiii. Available online: https://www.salvaticopiii.ro/sites/ro/files/2023-11/studiu-violenta-asupra-copilului-salvati-copiii-2021_1.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Panișoară, G. (2024). Reziliența: Calea spre succes si echilibru pentru copii și părinții lor [Resilience: The pathway to success for children and their parents]. Polirom. [Google Scholar]

- Pante, M., Rysdik, A., Krimberg, J. S., & de Almeida, R. M. M. (2022). Relation between testosterone, cortisol and aggressive behavior in humans: A systematic review. Psico, 53(1), e37133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, P. D., Bishop, A., & Younan, R. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences and early maladaptive schemas in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(3), 569–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rada, C. (2014). Violence against women by male partners and against children within the family: Prevalence, associated factors, and intergenerational transmission in Romania, a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 14, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahme, C., Haddad, C., Akel, M., Khoury, C., Obeid, H., Fekih-Romdhane, F., Hallit, S., & Obeid, S. (2025). The relationship between early maladaptive schemas and intimate partner violence against women: The moderating effect of childhood trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Martinez, A., Sarrate-Costa, C., & Moya-Albiol, L. (2022). Reactive vs proactive aggression: A differential psychobiological profile? Conclusions derived from a systematic review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 136, 104626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebalo, I., Königová, M. P., Sebalo Vňuková, M., Anders, M., & Ptáček, R. (2023). The associations of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) with substance use in young adults: A systematic review. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shorey, R. C., Strauss, C., Zapor, H., & Stuart, G. L. (2017). Dating violence perpetration: Associations with early maladaptive schemas. Violence and Victims, 32(4), 714–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigre-Leirós, V. L., Carvalho, J., & Nobre, P. (2013). Early maladaptive schemas and aggressive sexual behavior: A preliminary study with male college students. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(7), 1764–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supol, M., Satyen, L., Ghayour-Minaie, M., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2021). Effects of family violence exposure on adolescent academic achievement: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(5), 1042–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, P. F., & Dozois, D. J. (2009). Another perspective on trait aggressiveness: Overlap with early maladaptive schemas. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(5–6), 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trip, S. (2006). The Romanian version of young schema questionnaire—Short form 3 (YSQ-S3). Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 6(2), 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2024). Sexual violence. UNICEF. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/violence/sexual-violence/#status (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Van Bokhoven, I., Van Goozen, S. H., Van Engeland, H., Schaal, B., Arseneault, L., Séguin, J. R., Assaad, J.-M., Nagin, D. S., Vitaro, F., & Tremblay, R. E. (2006). Salivary testosterone and aggression, delinquency, and social dominance in a population-based longitudinal study of adolescent males. Hormones and Behavior, 50(1), 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C., Kuss, D. J., & Griffiths, M. D. (2023). Early maladaptive schemas and behavioural addictions: A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 105, 102340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilariño, M., Amado, B. G., Seijo, D., Selaya, A., & Arce, R. (2022). Consequences of child maltreatment victimisation in internalising and externalising mental health problems. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 27(2), 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Chen, M., & Chen, Z. (2023). The effect of relative deprivation on aggressive behavior of college students: A moderated mediation model of belief in a just world and moral disengagement. BMC Psychology, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., Gao, Y., Liu, J., Bai, R., & Liu, X. (2023). Reciprocal associations between early maladaptive schemas and depression in adolescence: Long-term effects of childhood abuse and neglect. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 17, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welburn, K., Coristine, M., Dagg, P., Pontefract, A., & Jordan, S. (2002). The Schema Questionnaire—Short Form: Factor analysis and relationship between schemas and symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 26, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, C. S., & Maxfield, M. G. (2001). An update on the “cycle of violence”. Research in brief. Available online: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED451313.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- World Health Organization [WHO]. (2024). Youth violence. WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/youth-violence (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- World Vision Romania Foundation. (2024). Bunăstarea copilului din mediul rural din România [Child well-being in rural Romania]. Available online: https://worldvision.ro/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Raportul-Bunastarea-copilului-din-mediul-rural-2024.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Wright, M. O. D., Crawford, E., & Del Castillo, D. (2009). Childhood emotional maltreatment and later psychological distress among college students: The mediating role of maladaptive schemas. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(1), 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakın, D., & Arntz, A. (2023). Understanding the reparative effects of schema modes: An in-depth analysis of the healthy adult mode. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1204177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, O., Marais, I., Lee, C. W., & Correia, H. (2023). The YSQ-R: Predictive Validity and comparison to the short and long form young schema questionnaire. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, J. E., Klosko, J. S., & Weishaar, M. E. (2003). Schema therapy: A practitioner’s guide. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yousefpour, N. (2022). Predicting bullying and antisocial behaviors based on early maladaptive schemas and defense mechanisms in drug abusers. Scientific Quarterly Research on Addiction, 16(63), 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelli, A., Dodge, K. A., Lochman, J. E., & Laird, R. D. (1999). The distinction between beliefs legitimizing aggression and deviant processing of social cues: Testing measurement validity and the hypothesis that biased processing mediates the effects of beliefs on aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(1), 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zonnevijlle, M., & Hildebrand, M. (2019). Like parent, like child? Exploring the association between early maladaptive schemas of adolescents involved with Child Protective Services and their parents. Child & Family Social Work, 24(2), 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Score | N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violence in school | 895 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.1933 | 0.24505 |

| Violence outside school | 893 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 0.2383 | 0.27813 |

| Valid N (listwise) | 893 |

| 95% C.I. | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect and Total Effects | Estimate | SE | Lower | Upper | β | z | p | |

| Indirect | ab | 0.019 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.032 | 0.019 | 2.90 | 0.004 |

| Component | a | 1.008 | 0.2855 | 0.474 | 1.526 | 0.117 | 3.54 | <0.001 |

| b | 0.019 | 0.003 | 0.010 | 0.026 | 0.165 | 5.08 | <0.001 | |

| Direct | c | 0.187 | 0.032 | 0.117 | 0.261 | 0.186 | 5.72 | <0.001 |

| Total | ab + c | 0.206 | 0.032 | 0.1353 | 0.276 | 0.2056 | 6.27 | <0.001 |

| Pearson | Spearman | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | rho | p | |||||

| MA | - | EI | 0.521 | *** | <0.001 | 0.496 | *** | <0.001 |

| MA | - | US | 0.466 | *** | <0.001 | 0.438 | *** | <0.001 |

| MA | - | ET | 0.491 | *** | <0.001 | 0.513 | *** | <0.001 |

| MA | - | PU | 0.685 | *** | <0.001 | 0.670 | *** | <0.001 |

| EI | - | US | 0.420 | *** | <0.001 | 0.386 | *** | <0.001 |

| EI | - | ET | 0.370 | *** | <0.001 | 0.391 | *** | <0.001 |

| EI | - | PU | 0.613 | *** | <0.001 | 0.586 | *** | <0.001 |

| US | - | ET | 0.516 | *** | <0.001 | 0.523 | *** | <0.001 |

| US | - | PU | 0.567 | *** | <0.001 | 0.520 | *** | <0.001 |

| ET | - | PU | 0.503 | *** | <0.001 | 0.524 | *** | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rada, C.; Neagu, A.-E.; Marinescu, V.; Rodideal, A.-A.; Lunga, R.-A. The Impact of Childhood Abuse on the Development of Early Maladaptive Schemas and the Expression of Violence in Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070854

Rada C, Neagu A-E, Marinescu V, Rodideal A-A, Lunga R-A. The Impact of Childhood Abuse on the Development of Early Maladaptive Schemas and the Expression of Violence in Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):854. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070854

Chicago/Turabian StyleRada, Cornelia, Alexandra-Elena Neagu, Valentina Marinescu, Anda-Anca Rodideal, and Robert-Andrei Lunga. 2025. "The Impact of Childhood Abuse on the Development of Early Maladaptive Schemas and the Expression of Violence in Adolescents" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070854

APA StyleRada, C., Neagu, A.-E., Marinescu, V., Rodideal, A.-A., & Lunga, R.-A. (2025). The Impact of Childhood Abuse on the Development of Early Maladaptive Schemas and the Expression of Violence in Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 854. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070854