Exploring Differential Patterns of Dissociation: Severity and Dimensions Across Diverse Trauma Experiences and/or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Structure of the Survey

- (i)

- Informed consent form: participants should provide their consent to be included in the study.

- (ii)

- Sociodemographic data: sex, age, years of formal education (based on the Italian schooling system), marital and employment status, history of neurological and psychiatric conditions or previous psychopathological diagnosis, use of psychotropic drugs or any ongoing psychological treatments, and average hours of sleep per night.

- (iii)

- The Dissociative Experiences Scale-II (DES-II) is a 28-item self-report scale that measures dissociative experiences in daily life related to depersonalization, derealization, amnesia, and absorption (Saggino et al., 2020). This scale is based on the commonly held concept that dissociation is a continuum and thus, each item varies between 0% (“Never”) and 100% (“Always”), describing how often a person has a particular experience. The total DES-II score is represented by the mean of all 28 item scores, with higher total scores associated with dissociative tendencies. According to the three-factor model proposed by Carlson et al. (Carlson et al., 1993), three dimensions can be distinguished: Amnesia, Depersonalization/Derealization and Absorption. Amnesia dimension reflects dissociative memory loss, where individuals experience gaps in their recollection of personal experiences, such as not remembering how they arrived at a place or forgetting actions they have taken. On the other hand, Depersonalization/Derealization dimension encompasses a sense of detachment from oneself and mental processes or a sense of unreality of the self. Individuals may feel as though they are observing their own actions from the outside or experience the world around them as unreal or distorted. Finally, Absorption dimension involves deep immersion in thoughts or experiences, where individuals may become absorbed in mental activities and lose awareness of their surroundings. In addition to the DES-II scores, we computed the DES-taxon score (DES-T), which consists of the average of eight specific DES-II items (i.e., items 3, 5, 7, 8, 12, 13, 22, and 27) and allows for the measurement of pathological dissociation (Waller et al., 1996).

- (iv)

- The Italian version of the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): patients are asked to rate the frequency of symptoms associated with ADHD they have experienced within the past 6 months. The scale consists of 18 items answered on a 5-point Likert scale from “Never” to “Very often” evaluating both Inattention and Hyperactivity-Impulsivity. Ratings of sometimes, often, or very often on items 1–3, 9, 12, 16, and 18 are assigned one point (ratings of never or rarely are assigned zero points). For the remaining 11 items, ratings of often or very often are assigned one point (ratings of never, rarely, or sometimes are assigned zero points). The symptoms profile of the subjects can be obtained by summing the number of points within each symptom subtype, such that subtype scores can range from 0 to 9. A score ≥ 6 on the Inattention and/or Hyperactivity-Impulsivity subscale is considered symptomatic of ADHD (Adler et al., 2019).

- (v)

- The Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) was used to evaluate current subjective distress in response to a specific traumatic event (Craparo et al., 2013). The scale consists of 22-items answered on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Extremely”) describing manifestations that may occur after a stressful life event. It comprises three subscales reflecting the major symptom clusters of post-traumatic stress: intrusion, avoidance, and hyper-arousal (Craparo et al., 2013). A score of ≥ 33 indicates a probable diagnosis of PTSD (Creamer et al., 2003).

- (vi)

- The Adverse Childhood Experience questionnaire (ACE) to evaluates adverse childhood experiences. Participants are asked to respond with “Yes” or “No” to 10-items evaluating two sets of adverse childhood experiences: childhood abuse in terms of events that directly affected the respondent (i.e., physical, emotional, or sexual abuse and physical or emotional neglect), and household dysfunction represented by events that happened to other family members and may have indirectly affected the respondent (i.e., parental divorce, domestic violence towards the (step)mother, parental mental health problems, substance use, or imprisonment of a family member) (Van der Feltz-Cornelis & de Beurs, 2023).

2.3. Groups Classification

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants Characteristics

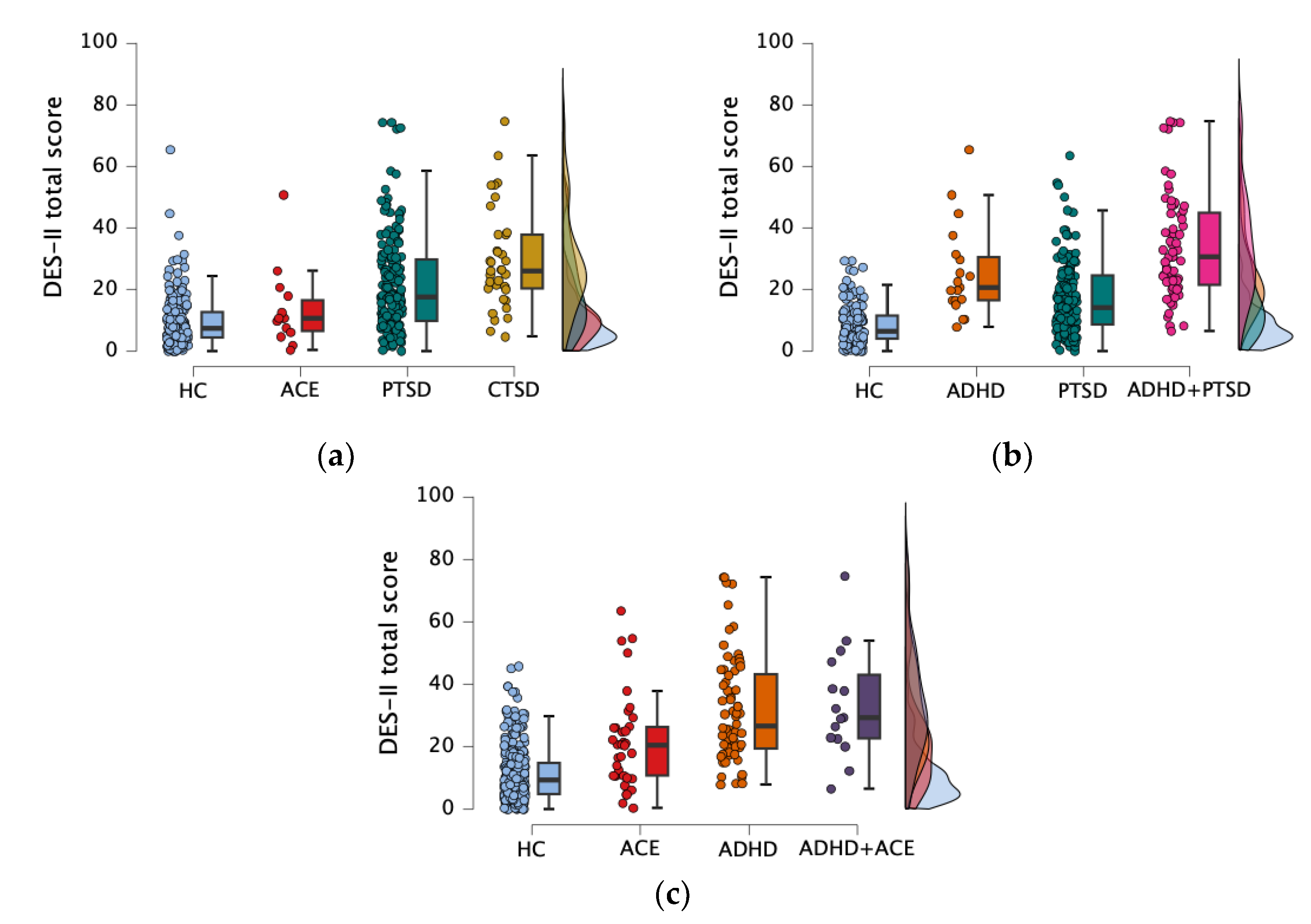

3.2. How Dissociative Dimensions Differ Across Distinct Trauma Profiles?

3.2.1. Participants Classification According to PTSD and ACEs Manifestations

3.2.2. Comparison Between PTSD and ACE Groups on Demographical and Psychological Variables

3.3. How Dissociative Dimensions Differ Across PTSD and ADHD Manifestations?

3.3.1. Participants Classification According to PTSD and ADHD Manifestations

3.3.2. Comparison Between PTSD and ADHD Groups on Demographical and Psychological Variables

3.4. How Dissociative Dimensions Differ Across ACEs-Related and ADHD Manifestations?

3.4.1. Participants Classification According to ACEs-Related and ADHD Manifestations

3.4.2. Comparison Between ACE and ADHD Groups on Demographical and Psychological Variables

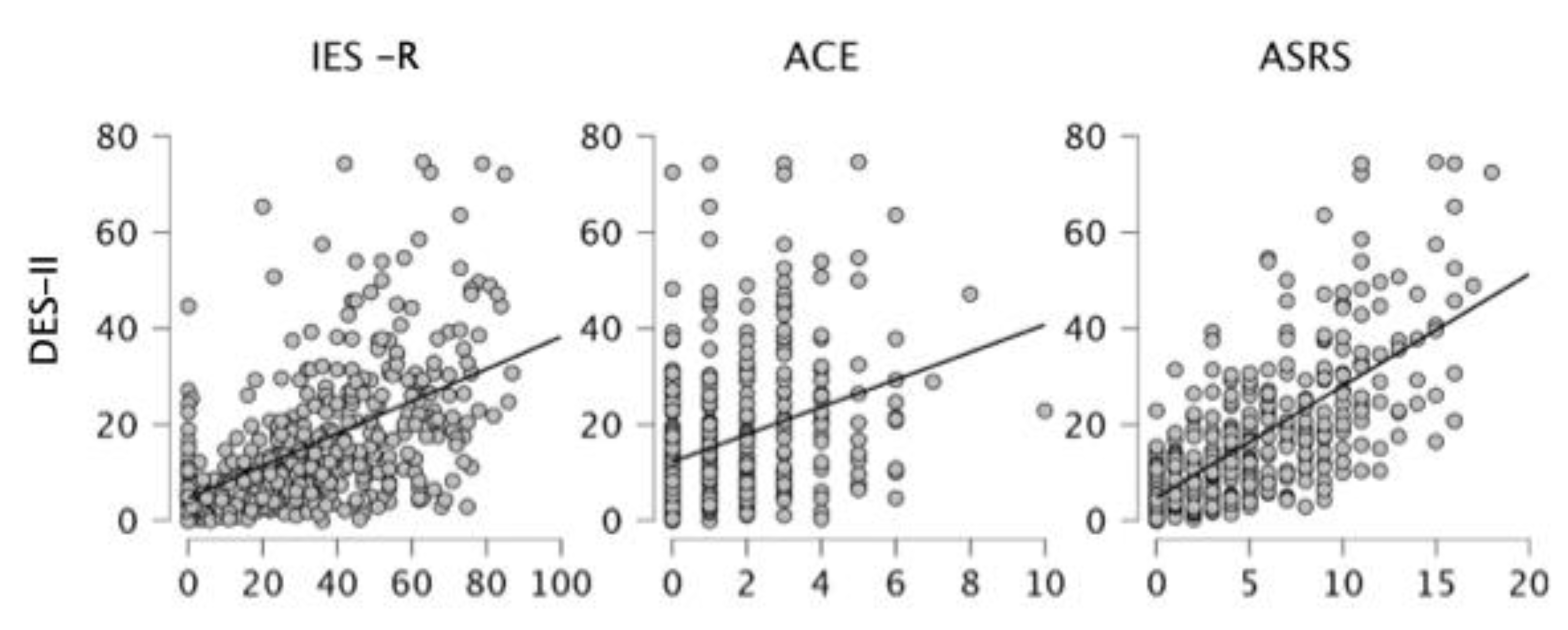

3.5. Correlation Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACEs | Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| ADHD | Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

| ASRS | Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale |

| CTSD | Complex traumatic stress disorders |

| DES | Dissociative Experience Scale |

| IES-R | Impact of Event-Revised Scale |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

References

- Adams, Z., Adams, T., Stauffacher, K., Mandel, H., & Wang, Z. (2020). The effects of inattentiveness and hyperactivity on posttraumatic stress symptoms: Does a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder matter? Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(9), 1246–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, L. A., Faraone, S. V., Sarocco, P., Atkins, N., & Khachatryan, A. (2019). Establishing US norms for the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) and characterising symptom burden among adults with self-reported ADHD. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 73(1), e13260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J. G., Console, D. A., & Lewis, L. (1999). Dissociative detachment and memory impairment: Reversible amnesia or encoding failure? Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40(2), 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Toward a new understanding of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder pathophysiology: An important role for prefrontal cortex dysfunction. CNS Drugs, 23(1), 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedard-Gilligan, M., & Zoellner, L. A. (2012). Dissociation and memory fragmentation in post-traumatic stress disorder: An evaluation of the dissociative encoding hypothesis. Memory, 20(3), 277–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, E. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174(12), 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntsen, D., & Rubin, D. C. (2014). Involuntary memories and dissociative amnesia: Assessing key assumptions in posttraumatic stress disorder research. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(2), 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bob, P., & Konicarova, J. (2018). Neural dissolution, dissociation and stress in ADHD. ADHD, Stress, and Development, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewin, C. R. (2011). The nature and significance of memory disturbance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 203–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N. M., Brown, S. N., Briggs, R. D., Germán, M., Belamarich, P. F., & Oyeku, S. O. (2017). Associations between adverse childhood experiences and ADHD diagnosis and severity. Academic Pediatrics, 17(4), 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R. J. (2006). Different types of “dissociation” have different psychological mechanisms. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 7(4), 7–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardeña, E. (1994). The domain of dissociation. In Dissociation: Clinical and theoretical perspectives. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cardeña, E., & Carlson, E. (2011). Acute stress disorder revisited. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, E. B., Dalenberg, C., & McDade-Montez, E. (2012). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder part I: Definitions and review of research. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(5), 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, E. B., Putnam, F. W., Ross, C. A., Torem, M., Coons, P., Dill, D. L., Loewenstein, R. J., & Braun, B. G. (1993). Validity of the dissociative experiences scale in screening for multiple personality disorder: A multicenter study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(7), 1030–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, D., & Ehlers, A. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(2), 319–345. [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M., Garvert, D. W., Brewin, C. R., Bryant, R. A., & Maercker, A. (2013). Evidence for proposed ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD: A latent profile analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 20706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coriat, I. H. (1907). Review of The major symptoms of hysteria. The Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 2(5), 235–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craparo, G., Faraci, P., Rotondo, G., & Gori, A. (2013). The impact of event scale revised: Psychometric properties of the Italian version in a sample of flood victims. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 9, 1427–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, M., Bell, R., & Failla, S. (2003). Psychometric properties of the impact of event scale—Revised. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(12), 1489–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalenberg, C., & Carlson, E. B. (2012). Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder part II: How theoretical models fit the empirical evidence and recommendations for modifying the diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 4(6), 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M., Ester, P., & Kaczmirek, L. (2011). Social and behavioral research and the internet: Advances in applied methods and research strategies. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dell, P. F. (2006). The multidimensional inventory of dissociation (MID) a comprehensive measure of pathological dissociation. Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, 7(2), 77–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, M. L., Rodebaugh, T. L., Flores, S., & Zacks, J. M. (2023). Impaired prediction of ongoing events in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychologia, 188, 108636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, T., Sugiyama, T., & Someya, T. (2006). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and dissociative disorder among abused children. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 60(4), 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., & Mick, E. (2006). The age-dependent decline of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A meta-analysis of follow-up studies. Psychological Medicine, 36(2), 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foote, B., Smolin, Y., Kaplan, M., Legatt, M. E., & Lipschitz, D. (2006). Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(4), 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J. D., & Connor, D. F. (2009). ADHD and posttraumatic stress disorder. Current Attention Disorders Reports, 1(2), 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuermaier, A. B. M., Tucha, L., Guo, N., Mette, C., Müller, B. W., Scherbaum, N., & Tucha, O. (2022). It takes time: Vigilance and sustained attention assessment in adults with ADHD. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giesbrecht, T., Merckelbach, H., Geraerts, E., & Smeets, E. (2004). Dissociation in undergraduate students: Disruptions in executive functioning. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 192(8), 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, Y., Priegnitz, U., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Tucha, L., Tucha, O., Aschenbrenner, S., Weisbrod, M., & Garcia Pimenta, M. (2020). Testing the relation between ADHD and hyperfocus experiences. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 107, 103789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E. A., Brown, R. J., Mansell, W., Fearon, R. P., Hunter, E. C. M., Frasquilho, F., & Oakley, D. A. (2005). Are there two qualitatively distinct forms of dissociation? A review and some clinical implications. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., Jones, L., & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R. F., Gough, A., O’Kane, N., McKeown, G., Fitzpatrick, A., Walker, T., McKinley, M., Lee, M., & Kee, F. (2018). Ethical issues in social media research for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 108(3), 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Fyvie, C., & Karatzias, T. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder and complex posttraumatic stress disorder in DSM-5 and ICD-11: Clinical and behavioral correlates. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(2), 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janet, P. (1907). The major symptoms of hysteria: Fifteen lectures given in the medical school of harvard university (2nd ed., Vol. 44). Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lanius, R. A., Brand, B., Vermetten, E., Frewen, P. A., & Spiegel, D. (2012). The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: Rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depression and Anxiety, 29(8), 701–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, L., Cecora, V., Rossi, R., Niolu, C., Siracusano, A., & Di Lorenzo, G. (2019). Dissociative symptoms in complex post-traumatic stress disorder and in post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Psychopathology, 25(4), 212–219. [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Candelas, C., Corbeil, T., Wall, M., Posner, J., Bird, H., Canino, G., Fisher, P. W., Suglia, S. F., & Duarte, C. S. (2021). ADHD and risk for subsequent adverse childhood experiences: Understanding the cycle of adversity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 62(8), 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyssenko, L., Schmahl, C., Bockhacker, L., Vonderlin, R., Bohus, M., & Kleindienst, N. (2018). Dissociation in psychiatric disorders: A meta-analysis of studies using the dissociative experiences scale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makris, N., Biederman, J., Monuteaux, M. C., & Seidman, L. J. (2009). Towards conceptualizing a neural systems-based anatomy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Developmental Neuroscience, 31(1–2), 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt Alderson, R., Kasper, L. J., Hudec, K. L., & Patros, C. H. G. (2013). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and working memory in adults: A meta-analytic review. Neuropsychology, 27(3), 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mette, C. (2023). Time perception in adult ADHD: Findings from a decade—A review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L., Fang, X., Mercy, J., Perou, R., & Grosse, S. D. (2008). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and child maltreatment: A population-based Study. Journal of Pediatrics, 153(6), 851–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, F. W. (1991). Dissociative disorders in children and adolescents: A developmental perspective. Psychiatric Clinics, 14(3), 519–531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saggino, A., Molinengo, G., Rogier, G., Garofalo, C., Loera, B., Tommasi, M., & Velotti, P. (2020). Improving the psychometric properties of the dissociative experiences scale (DES-II): A Rasch validation study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sar, V., & Ross, C. (2006). Dissociative disorders as a confounding factor in psychiatric research. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 29(1), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalinski, I., Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2015). The shutdown dissociation scale (shut-D). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6, 25652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schalinski, I., Teicher, M. H., Nischk, D., Hinderer, E., Müller, O., & Rockstroh, B. (2016). Type and timing of adverse childhood experiences differentially affect severity of PTSD, dissociative and depressive symptoms in adult inpatients. BMC Psychiatry, 16(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, M., & Elbert, T. (2010). Dissociation following traumatic stress etiology and treatment. Journal of Psychology, 218(2), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeon, D., Knutelska, M., Nelson, D., & Guralnik, O. (2003). Feeling unreal: A depersonalization disorder update of 117 cases. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 64(9), 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somer, E., Soffer-Dudek, N., & Ross, C. A. (2017). The Comorbidity of daydreaming disorder (maladaptive daydreaming). Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 205(7), 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, M. (2000). Advances in the clinical assessment of dissociation: The SCID-D-R. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 64(2), 146–163. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor-Katz, N., Somer, E., Hesseg, R. M., & Soffer-Dudek, N. (2022). Could immersive daydreaming underlie a deficit in attention? The prevalence and characteristics of maladaptive daydreaming in individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(11), 2309–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ünver, H., & Karakaya, I. (2019). The assessment of the relationship between adhd and posttraumatic stress disorder in child and adolescent patients. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(8), 900–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Feltz-Cornelis, C. M., & de Beurs, E. (2023). The 10-item Adverse Childhood Experience International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ-10): Psychometric properties of the Dutch version in two clinical samples. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(2), 2216623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Hart, O., & Brom, D. (2000). When the victim forgets: Trauma-induced amnesia and its assessment in Holocaust survivors. In International handbook of human response to Trauma. Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- van der Kolk, B. A., & Fisler, R. (1995). Dissociation and the fragmentary nature of traumatic memories: Overview and exploratory study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(4), 505–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waller, N. G., Putnam, F. W., & Carlson, E. B. (1996). Types of dissociation and dissociative types: A taxometric analysis of dissociative experiences. Psychological Methods, 1(3), 300–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, R., Daskalakis, N. P., Lehrner, A., Desarnaud, F., Bader, H. N., Makotkine, I., Flory, J. D., Bierer, L. M., & Meaney, M. J. (2014). Influences of maternal and paternal PTSD on epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene in Holocaust survivor offspring. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(8), 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanarini, M. C., Williams, A. A., Lewis, R. E., Bradford Reich, R., Vera, S. C., Marino, M. F., Levin, A., Yong, L., & Frankenburg, F. R. (1997). Reported pathological childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(8), 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| HC Group (n = 180) A | ACE Group (n = 14) B | PTSD Group (n = 169) C | CTSD Group (n = 37) D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | χ2 | p | |

| Age | 34.30 ± 10.57 | 34.29 ± 10.34 | 29.83 ± 7.16 | 31.14 ± 11.78 | 21.779 | <0.001 C < A |

| Educational level (ys) | 16.14 ± 2.74 | 13.71 ± 4.43 | 15.80 ± 2.59 | 15.00 ± 3.11 | 7.117 | 0.068 |

| Sex | 97 M/83 F | 6 M/8 F | 67 M/102 F | 19 M/18 F | 7.463 | 0.059 |

| Neuropsychiatric Variables | ||||||

| IES-R | 15.35 ± 11.05 | 22.64 ± 6.52 | 51.63 ± 13.79 | 58.11 ± 13.73 | 302.281 | <0.001 C > A,B D > A,B |

| ACE questionnaire | 0.76 ± 0.96 | 4.64 ± 0.84 | 1.17 ± 1.13 | 5.08 ± 1.32 | 153.828 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < B,D |

| DES-II total | 9.62 ± 8.67 | 13.57 ± 12.81 | 21.04 ± 15.50 | 29.36 ± 16.13 | 100.085 | <0.001 D > A,B,C C > A |

| DES-T | 6.64 ± 7.96 | 13.12 ± 12.32 | 16.74 ± 15.00 | 25.27 ± 16.85 | 93.278 | <0.001 D > A,C C > A |

| DES-II Amnesia | 4.97 ± 6.85 | 10.36 ± 11.53 | 11.93 ± 13.77 | 18.96 ± 14.02 | 63.073 | <0.001 A < C,D D > C |

| DES-II Depersonalization | 2.87 ± 7.35 | 9.28 ± 17.67 | 11.91 ± 16.77 | 20.40 ± 21.66 | 73.734 | <0.001 A < C,D D > C |

| DES-II Absorption | 16.81 ± 14.71 | 16.55 ± 16.35 | 33.56 ± 22.56 | 40.81 ± 19.20 | 87.316 | <0.001 A < C,D B < C,D |

| ASRS Impulsiveness | 1.31 ± 1.60 | 1.93 ± 1.54 | 2.95 ± 2.32 | 3.62 ± 2.09 | 69.214 | <0.001 A < C,D |

| ASRS Inattention | 1.89 ± 2.32 | 2.86 ± 2.35 | 3.37 ± 2.77 | 4.22 ± 2.17 | 44.173 | <0.001 A < C,D |

| ASRS total | 3.20 ± 3.37 | 4.79 ± 3.62 | 6.31 ± 4.55 | 7.84 ± 3.77 | 66.217 | <0.001 A < C,D |

| HC (n = 175) A | ADHD (n = 19) B | PTSD (n = 142) C | ADHD+PTSD (n = 64) D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | χ2 | p | |

| Age | 34.86 ± 10.76 | 29.11 ± 6.14 | 30.85 ± 8.38 | 28.33 ± 7.44 | 38.587 | <0.001 A > B,C,D D < C |

| Educational level (ys) | 15.89 ± 2.99 | 16.68 ± 2.43 | 15.81 ± 2.50 | 15.33 ± 3.10 | 4.470 | 0.215 |

| Sex | 96 M/79 F | 7 M/12 F | 64 M/78 F | 22 M/42 F | 9.416 | 0.024 |

| Neuropsychiatric Variables | ||||||

| IES-R | 15.97 ± 10.79 | 15.00 ± 12.53 | 49.63 ± 12.00 | 59.81 ± 15.51 | 304.338 | <0.001 A < C,D B < C,D |

| ACE questionnaire | 1.03 ± 1.41 | 1.11 ± 1.20 | 1.64 ± 1.81 | 2.38 ± 2.00 | 31.929 | <0.001 A < C,D C < D |

| DES-II total | 8.21 ± 6.19 | 25.51 ± 14.92 | 17.34 ± 12.15 | 34.06 ± 17.21 | 157.060 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < D |

| DES-T | 6.07 ± 6.16 | 16.71 ± 17.17 | 13.61 ± 11.37 | 28.61 ± 18.71 | 115.857 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < D |

| DES-II Amnesia | 4.14 ± 5.45 | 16.58 ± 12.21 | 9.86 ± 10.52 | 20.60 ± 17.70 | 95.462 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < B, D |

| DES-II Depersonalization | 2.02 ± 4.11 | 15.44 ± 21.37 | 9.17 ± 13.23 | 22.92 ± 22.98 | 95.927 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < D |

| DES-II Absorption | 14.23 ± 11.44 | 40.44 ± 20.60 | 27.63 ± 18.51 | 50.91 ± 21.14 | 148.789 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < D |

| ASRS Impulsiveness | 1.12 ± 1.28 | 3.53 ± 2.50 | 2.20 ± 1.73 | 4.98 ± 2.24 | 129.224 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < D |

| ASRS Inattention | 1.43 ± 1.54 | 6.84 ± 1.80 | 2.11 ± 1.72 | 6.66 ± 1.58 | 190.072 | <0.001 A<B,C,D C < B,D |

| ASRS total | 2.55 ± 2.41 | 10.37 ± 3.15 | 4.31 ± 3.01 | 11.64 ± 2.55 | 202.215 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < B,D |

| HC (n = 281) A | ADHD (n = 68) B | ACE (n = 36) C | ADHD+ACE (n = 15) D | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | χ2 | p | |

| Age | 33.05 ± 9.76 | 28.34 ± 6.06 | 33.14 ± 11.50 | 29.27 ± 11.02 | 25.433 | <0.001 B < A,C |

| Educational level (ys) | 16.09 ± 2.60 | 15.51 ± 2.89 | 14.00 ± 3.36 | 16.20 ± 3.51 | 12.741 | 0.005 C < A |

| Sex | 141 M/140 F | 23 M/45 F | 19 M/17 F | 6 M/9 F | 2.667 | 0.102 |

| Neuropsychiatric Variables | ||||||

| IES-R | 29.41 ± 19.79 | 47.41 ± 24.77 | 43.83 ± 19.28 | 59.27 ± 18.09 | 55.922 | <0.001 A < B,C,D |

| ACE questionnaire | 0.84 ± 1.00 | 1.43 ± 1.18 | 4.92 ± 0.87 | 5.07 ± 1.83 | 155.960 | <0.001 A < B,C,D B < C,D |

| DES-II total | 11.13 ± 8.96 | 31.77 ± 17.00 | 21.47 ± 15.26 | 33.57 ± 17.59 | 123.419 | <0.001 A < B,C,D B > C |

| DES-T | 8.29 ± 8.33 | 24.93 ± 18.70 | 18.47 ± 13.69 | 30.25 ± 20.11 | 92.949 | <0.001 A < B,C,D |

| DES-II Amnesia | 5.65 ± 7.19 | 19.46 ± 17.08 | 14.91 ± 13.21 | 20.67 ± 14.88 | 91.960 | <0.001 A < B,C,D |

| DES-II Depersonalization | 4.09 ± 7.87 | 20.32 ± 21.95 | 14.07 ± 17.84 | 25.22 ± 26.40 | 80.037 | <0.001 A < B,C,D |

| DES-II Absorption | 19.06 ± 15.35 | 49.17 ± 22.20 | 29.40 ± 21.22 | 45.55 ± 17.34 | 110.728 | <0.001 A < B,C,D B > C |

| ASRS Impulsiveness | 1.53 ± 1.60 | 4.46 ± 2.49 | 2.17 ± 1.38 | 5.53 ± 1.46 | 106.648 | <0.001 A < B,D C < B,D |

| ASRS Inattention | 1.59 ± 1.61 | 6.79 ± 1.60 | 2.83 ± 1.65 | 6.27 ± 1.71 | 192.666 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < B,D |

| ASRS total | 3.12 ± 2.80 | 11.25 ± 2.86 | 5.00 ± 2.55 | 11.80 ± 2.08 | 192.106 | <0.001 A < B,C,D C < B,D |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Esposito, R.; Schettino, E.M.; Buonincontri, V.; Vitale, C.; Santangelo, G.; Maggi, G. Exploring Differential Patterns of Dissociation: Severity and Dimensions Across Diverse Trauma Experiences and/or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070850

Esposito R, Schettino EM, Buonincontri V, Vitale C, Santangelo G, Maggi G. Exploring Differential Patterns of Dissociation: Severity and Dimensions Across Diverse Trauma Experiences and/or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):850. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070850

Chicago/Turabian StyleEsposito, Rosario, Eduardo Maria Schettino, Veronica Buonincontri, Carmine Vitale, Gabriella Santangelo, and Gianpaolo Maggi. 2025. "Exploring Differential Patterns of Dissociation: Severity and Dimensions Across Diverse Trauma Experiences and/or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070850

APA StyleEsposito, R., Schettino, E. M., Buonincontri, V., Vitale, C., Santangelo, G., & Maggi, G. (2025). Exploring Differential Patterns of Dissociation: Severity and Dimensions Across Diverse Trauma Experiences and/or Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Symptoms. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 850. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070850