Perceptions of Multiple Perpetrator Rape in the Courtroom

Abstract

1. Introduction

The Present Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Design

2.3. Materials

Trial Questionnaire

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Data Analytic Plan

3. Results

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | We acknowledge that the terms “victim” or “survivor” may be used to refer to someone who has experienced a sexual assault. We use “victim” in this paper because it is more commonly used in the criminal justice context (i.e., the courtroom), which is the focus of the present study. |

| 2 | Complicating matters, crime reporting in some countries does not distinguish between MPR and other forms of sexual assault (World Population Review, 2025), making it difficult to determine differences in the prevalence of MPR across countries. |

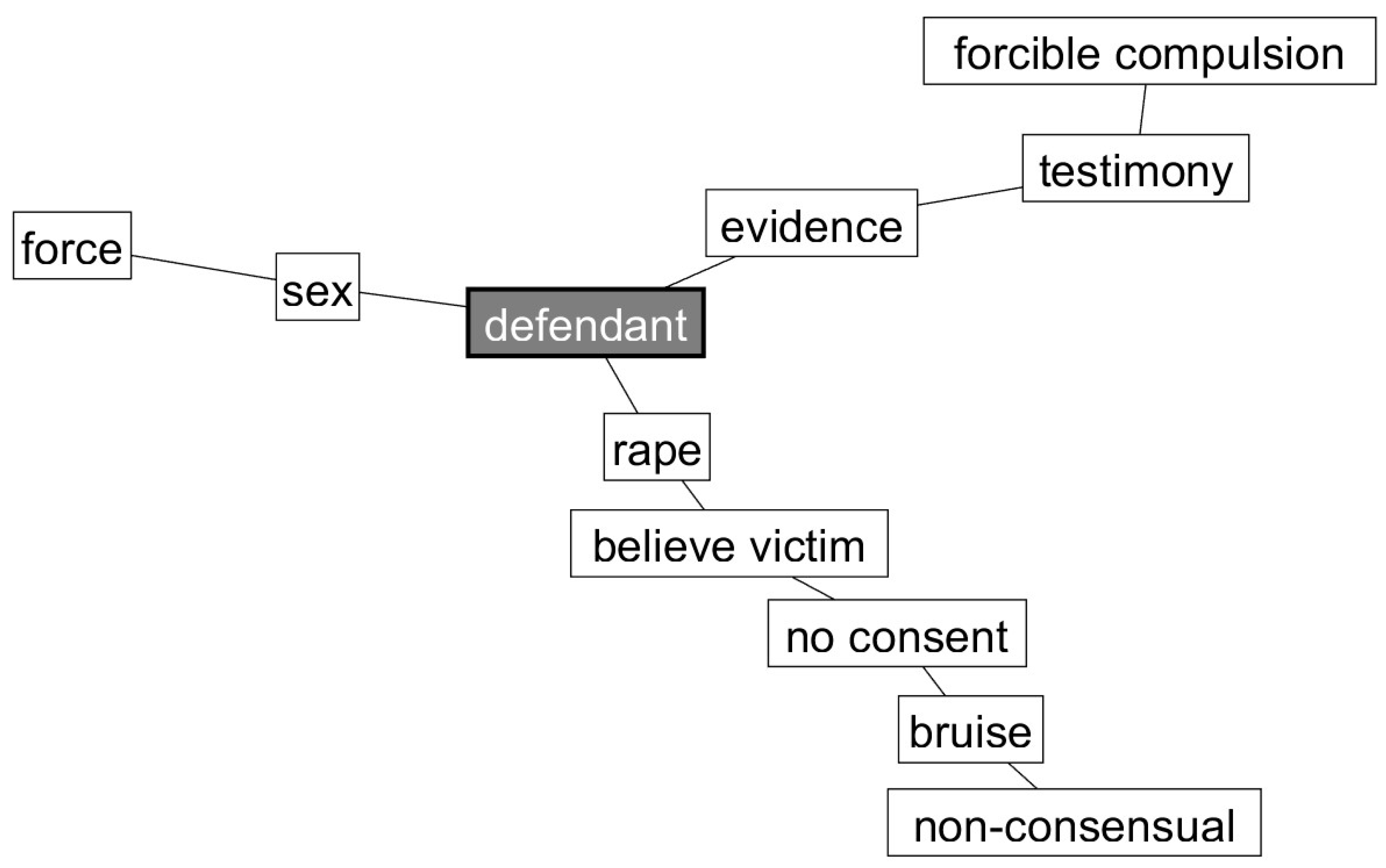

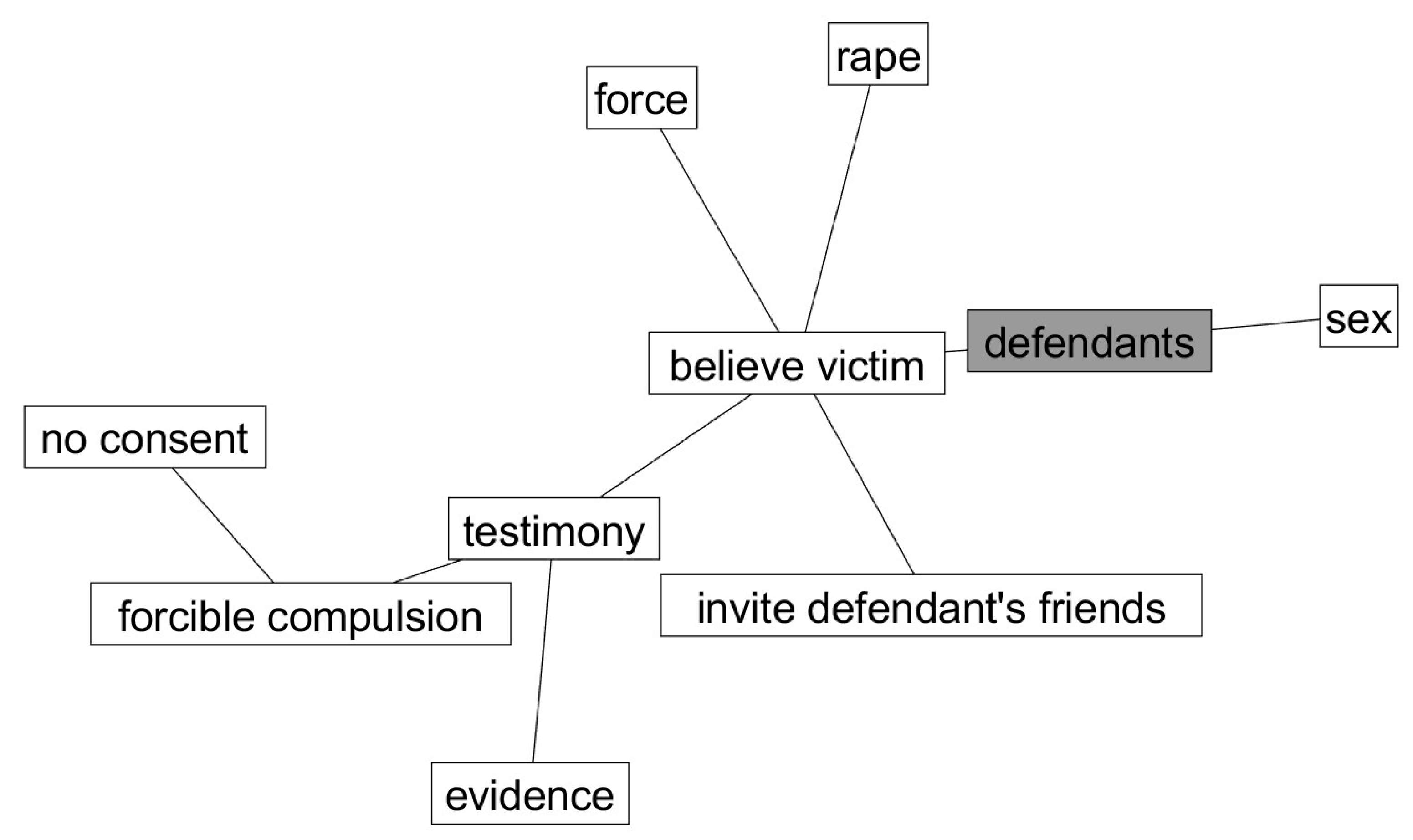

| 3 | Compared to other techniques, cognitive networks can provide more nuanced data by assessing not only the frequency of emerging themes but also visualizing the relations between these themes. They depict the relations between different concepts that participants mentioned in their open-ended responses. Each network contains nodes (i.e., the primary concepts that participants referred to) that are connected by links. Nodes are linked together based on the degree of relationship (e.g., similarity) between them in the open-ended responses. Commonly cited concepts are more central in the network and have more links to other nodes, and closely related concepts are linked directly to each other. |

| 4 | Using this method, researchers develop a detailed and realistic case summary of a trial to present to mock jurors in a vignette or other format (e.g., videorecorded slideshow). To increase ecological validity, the trial summary incorporates legally appropriate charges, realistic witnesses, admissible evidence, and pattern jury instructions. Participants are randomly assigned to different trial conditions that are the same except for the experimental manipulation. The structure of the mock trial summary follows an abbreviated version of the steps that occur in a real trial: It begins with opening statements by the prosecution and defense; followed by the prosecution’s presentation of their case, including prosecution witness testimony and defense cross-examination; the defense’s presentation of their case, including defense witness testimony and prosecution cross-examination; closing arguments from the prosecution and defense; and pattern jury instructions. Following this, jurors render a verdict and a series of other case judgments. |

| 5 | Because keywords are rank-ordered by their average TF-IDF scores, there is no fixed cutoff score or frequency required for inclusion. Terms with lower scores naturally fall to the bottom of the list and are unlikely to be selected. However, in cases where overall TF-IDF scores or term frequencies are extremely low and tightly clustered (e.g., when the most frequent terms appear only twice across all responses), there is little meaningful variance among terms. This results in distance matrices with limited range, producing networks that are either fully or nearly fully connected. Such networks offer little interpretive value, as they obscure meaningful distinctions between concepts. In these cases, we abandon network analysis in favor of alternative approaches better suited to sparse highly heterogeneous response data. |

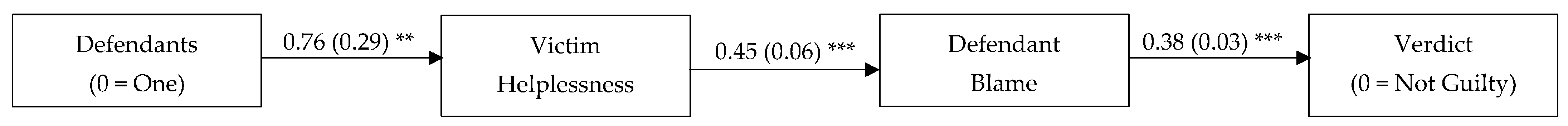

| 6 | We acknowledge the issue of temporal precedence involved in our indirect-effect analyses. However, we believe that this is justified for several reasons: (a) social psychological research practices do not require temporal precedence in research design to use indirect-effect analyses (Rucker et al., 2011) so long as causality is not being established (Winer et al., 2016). We should note that we do not intend to claim causal effects on the verdict. Moreover, it was necessary to measure perceptions of the victim and defendant after the verdict for methodological reasons given that the verdict was the most important, ecologically relevant outcome measure, and we did not want other measures to influence the ways in which jurors rendered their verdict. |

References

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective 1 June 2010, and 1 January 2017). Available online: https://www.apa.org/ethics/code (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Angelone, D. J., Mitchell, D., & Pilafova, A. (2007). Club drug use and intentionality in perceptions of rape victims. Sex Roles, 57, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, D. (2022, December 5). Nirbhaya 10 years on: The lives the Delhi gang rape changed. BBC News. Available online: www.bbc.com/news/world-63817388 (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Barnett, M., Sligar, K. B., & Wang, C. D. C. (2018). Religious affiliation, religiosity, gender, and rape myth acceptance: Feminist theory and rape culture. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33, 1219–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile, K. C., Smith, S. G., Kresnow, M., Khatiwada, S., & Leemis, R. W. (2022). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2016/2017 report on sexual violence. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Belyea, L., & Blais, J. (2023). Effect of pretrial publicity via social media, mock juror sex, and rape myth acceptance on juror decisions in a mock sexual assault trial. Psychology, Crime & Law, 29, 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, B. H., Golding, J. M., Neuschatz, J., Kimbrough, C., Reed, K., Magyarics, C., & Luecht, K. (2017). Mock juror sampling issues in jury simulation research: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 41, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, R. M., & Kerr, N. L. (1979). Use of the simulation method in the study of jury behavior: Some methodological considerations. Law and Human Behavior, 3, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownmiller, S. (1975). Against our will: Men, women and rape. Bantam. [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, E. M., & Scofield, J. E. (2018). Methods to detect low quality data and its implication for psychological research. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 2586–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulus, M. (2023). pwrss: Statistical power and sample size calculation tools (R package version 0.3.1). Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pwrss (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Burke, K. C., Golding, J. M., & Neuschatz, J. S. (2025). Sexual victimization and legal decision making. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 22, 41–62. [Google Scholar]

- Canan, S. N., & Levand, M. A. (2019). A feminist perspective on sexual assault. In W. T. O’Donohue, & P. A. Schewe (Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault and sexual assault prevention (pp. 3–16). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Crivatu, I. M., Horvath, M. A., & Massey, K. (2023). The impacts of working with victims of sexual violence: A rapid evidence assessment. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, T., & Woodhams, J. (2019). Introduction to the special issue on multiple perpetrator sexual offending. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 25, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, S. S. (1997). Illuminations and shadows from jury simulations. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakunmoju, S. B., Abrefa-Gyan, T., Maphosa, N., & Gutura, P. (2021). Rape myth acceptance: Gender and cross-national comparisons across the United States, South Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria. Sexuality & Culture, 25, 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fansher, A. K., & Welsh, B. (2023). A decade of decision making: Prosecutorial decision making in sexual assault cases. Social Sciences, 12(6), 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FBI. (2013). Uniform crime report: Crime in the United States. Available online: https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2013/crime-in-the-u.s.-2013/violent-crime/rape (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Figueroa, T., Winkley, L., & Wilkens, J. (2022, September 4). As D.A. considers SDSU gang rape claims, experts explain why such cases are challenging. Los Angeles Times. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2022-09-04/as-da-considers-sdsu-gang-rape-claims-experts-explain-why-such-cases-are-challenging (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Golding, J. M., Lynch, K. R., Renzetti, C. M., & Pals, A. M. (2023). Beyond the stranger in the woods: Investigating the complexity of adult rape cases in the courtroom. In B. H. Bornstein, & M. K. Miller (Eds.), Advances in psychology and law (Vol. 6, pp. 1–37). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Golding, J. M., Lynch, K. R., & Wasarhaley, N. E. (2016). Impeaching rape victims in criminal court: Does concurrent civil action hurt justice? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31, 3129–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golding, J. M., Malik, S., Jones, T. M., Burke, K. C., & Bottoms, B. L. (2020). Perceptions of child sexual abuse victims: A review of psychological research with implications for law. In J. Pozzulo, E. Pica, & C. Sheahan (Eds.), Memory and sexual misconduct: Psychological research for criminal justice (pp. 132–174). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R. K., Lee, S. C., & Thornton, D. (2022). Long-term recidivism rates among individuals at high risk to sexually reoffend. Sexual Abuse, 36, 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, D. J., Moss, A. J., Rosenzweig, C., Jaffe, S. N., Robinson, J., & Litman, L. (2023). Evaluating cloudresearch’s approved group as a solution for problematic data quality on MTurk. Behavior Research Methods, 55, 3953–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, M., & Gray, J. M. (2013). Multiple perpetrator rape in the courtroom. In M. Horvath, & J. Woodhams (Eds.), Handbook on the study of multiple perpetrator rape: A multidisciplinary response to an international problem (pp. 214–234). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Horvath, M., & Kelly, L. (2009). Multiple perpetrator rape: Naming an offence and initial research findings. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 15, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, M., & Woodhams, J. (2013). Handbook on the study of multiple perpetrator rape: A multidisciplinary response to an international problem. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Criminal Code. 720 ILCS §§ 5/11-1.20. n.d. Available online: https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs4.asp?ActID=1876&ChapterID=53&SeqStart=14900000&SeqEnd=16400000 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Jenkins, G., & Schuller, R. A. (2007). The impact of negative forensic evidence on mock jurors’ perceptions of a trial of drug-facilitated sexual assault. Law and Human Behavior, 31, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R., Fulu, E., Roselli, T., & Garcia-Moreno, C. (2013). Prevalence of and factors associated with non-partner rape perpetration: Findings from the UN multi-country cross-sectional study on men and violence in asia and the pacific. The Lancet Global Health, 1, e208–e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewkes, R., Sikweyiya, Y., Dunkle, K., & Morrell, R. (2015). Relationship between single and multiple perpetrator rape perpetration in South Africa: A comparison of risk factors in a population-based sample. BMC Public Health, 15, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, N. L., & Johnson, D. M. (2021). An empirical exploration into the measurement of rape culture. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, NP70–NP95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. M., Bottoms, B. L., & Stevenson, M. C. (2020). Child victim empathy mediates the influence of jurors’ sexual abuse experiences on child sexual abuse case judgments: Meta-analyses. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 26, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L. (2013). Naming and defining multiple perpetrator rape: The relationship between concepts and research. In M. Horvath, & J. Woodhams (Eds.), Handbook on the study of multiple perpetrator rape: A multidisciplinary response to an international problem (pp. xiv–xix). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kentucky Penal Code. §§ 510.040-510.060. n.d. Available online: https://apps.legislature.ky.gov/law/statutes/statute.aspx?id=19761 (accessed on 1 December 2023).

- Lees, S. (2002). Carnal knowledge: Rape on trial. Women’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levi, M. M., Lynch, K. R., & Golding, J. M. (2022). Strength versus sensitivity: The impact of attorney gender on juror perceptions and trial outcomes in a rape case. Violence Against Women, 28, 2010–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. R., Wasarhaley, N. E., Golding, J. M., & Simcic, T. A. (2013). Who bought the drinks? Juror perceptions of intoxication in a rape trial. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28, 3205–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E., & Monds, L. A. (2024). The effect of victim intoxication and crime type on mock jury decision-making. Psychology, Crime & Law, 30, 1231–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massachusetts General Laws. 265 §22. n.d. Available online: https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- MATLAB. (2024). MATLAB [version 24.1.0.2578822 (R2024a)]. MATLAB. [Google Scholar]

- McPhail, B. A. (2016). Feminist Framework Plus: Knitting feminist theories of rape etiology into a comprehensive model. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecikalski, A. A., Golding, J. M., Burke, K. C., & Neuschatz, J. S. (2024). Legal decision-making in an adult rape case involving DNA evidence. Violence Against Women. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Crime Victim Law Institute & National Women’s Law Center. (2016). Sexual assault statutes in the United States chart. Available online: https://ndaa.org/wp-content/uploads/sexual-assault-chart.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- O’Callaghan, E., Lorenz, K., Ullman, S. E., & Kirkner, A. (2021). A dyadic study of impacts of sexual assault disclosure on survivors’ informal support relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, NP5033–NP5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborn, K., Davis, J. P., Button, S., & Foster, J. (2021). Juror decision making in acquaintance and marital rape: The influence of clothing, alcohol, and preexisting stereotypical attitudes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36, NP2675–NP2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C., DeGue, S., Florence, C., & Lokey, C. N. (2017). Lifetime economic burden of rape among US adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 52, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, R. (2015). Recidivism of adult sexual offenders (pp. 1–6). United States Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking, SOMAPI Research Brief. Available online: https://smart.ojp.gov/somapi/chapter-5-adult-sex-offender-recidivism (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- RAINN. (2024). Perpetrators of sexual violence: Statistics. Available online: https://www.rainn.org/statistics/perpetrators-sexual-violence (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- RAINN. (2025a). Victims of sexual violence: Statistics. Available online: https://rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- RAINN. (2025b). What to expect from the criminal justice system. Available online: https://rainn.org/articles/what-expect-criminal-justice-system (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Rape Prevention and Education Program. (2024). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/sexual-violence/programs/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Regan, P. C., & Baker, S. J. (1998). The impact of child witness demeanor on perceived credibility and trial outcome in sexual abuse cases. Journal of Family Violence, 13, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennison, C. M. (2014). Feminist theory in the context of sexual violence. In G. Bruinsma, & D. Weisburd (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and criminal justice (pp. 1617–1627). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richer, L. A., Fields, L., Bell, S., Heppner, J., Dodge, J., Boccellari, A., & Shumway, M. (2017). Characterizing drug-facilitated sexual assault subtypes and treatment engagement of victims at a hospital-based rape treatment center. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32, 1524–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, L. (2024). Mock juries, real trials: How to solve (some) problems with jury science. Journal of Law and Society, 51, 324–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruva, C. L., Smith, K. D., & Sykes, E. C. (2023). Gender, generations, and guilt: Defendant gender and age affect jurors’ decisions and perceptions in an intimate partner homicide trial. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38, 12089–12112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulnier, A., Burke, K. C., & Bottoms, B. L. (2019). The effects of body-worn camera footage and eyewitness race on jurors’ perceptions of police use of force. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 37, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafran, L. H. (2005). Barriers to credibility: Understanding and countering rape myths. National Judicial Education Program Legal Momentum. [Google Scholar]

- Schuller, R. A., Ryan, A., Krauss, D., & Jenkins, G. (2013). Mock juror sensitivity to forensic evidence in drug facilitated sexual assaults. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 36, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, R. A., & Wall, A. M. (1998). The effects of defendant and complainant intoxication on mock jurors’ judgements of sexual assault. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 555–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schvaneveldt, R. W. (Ed.). (1990). Pathfinder associative networks: Studies in knowledge organization. Ablex Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Spohn, C., & Tellis, K. (2019). Sexual assault case outcomes: Disentangling the overlapping decisions of police and prosecutors. Justice Quarterly, 36, 383–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. (2022). Number of reported forcible rape cases in the United States from 1990 to 2022. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/191137/reported-forcible-rape-cases-in-the-usa-since-1990/ (accessed on 25 February 2025).

- Stuart, S. M., McKimmie, B. M., & Masser, B. M. (2019). Rape perpetrators on trial: The effect of sexual assault–related schemas on attributions of blame. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34, 310–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenney, E. R., MacCoun, R. J., Spellman, B. A., & Hastie, R. (2007). Calibration trumps confidence as a basis for witness credibility. Psychological Science, 18, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, S. E. (2013). Multiple perpetrator rape victimization: How it differs and why it matters. In M. Horvath, & J. Woodhams (Eds.), Handbook on the study of multiple perpetrator rape: A multidisciplinary response to an international problem (pp. 198–213). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Vetten, L., & Haffejee, S. (2005). Gang rape: A study in inner-city Johannesburg. South African Crime Quarterly, 12, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walinchus, L., Smyser, L., & Murphy, J. (2025, January 10). A vanishingly small number of violent sex crimes end in conviction, NBC News investigation shows. NBC News. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/specials/sex-assault-convictions/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Wall, A. M., & Schuller, R. A. (2000). Sexual assault and defendant/victim intoxication: Jurors’ perceptions of guilt. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, M. A., & Tangney, J. P. (2022). Too good to be true: Bots and bad data from Mechanical Turk. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, R. L., Krauss, D. A., & Lieberman, J. D. (2011). Mock jury research: Where do we go from here? Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 29, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, C. M., Strube, M. J., Cole, A. M., & Kagehiro, D. K. (1985). The impact of case characteristics and prior jury experience on jury verdicts. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 15, 409–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieberneit, M., Thal, S., Clare, J., Notebaert, L., & Tubex, H. (2024). Silenced survivors: A systematic review of the barriers to reporting, investigating, prosecuting, and sentencing of adult female rape and sexual assault. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25, 3742–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, T. R., & Bottoms, B. L. (2013). Attitudinal and individual differences influence perceptions of mock child sexual assault cases involving gay defendants. Journal of Homosexuality, 60, 734–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, E. S., Cervone, D., Bryant, J., McKinney, C., Liu, R. T., & Nadorff, M. R. (2016). Distinguishing mediational models and analyses in clinical psychology: Atemporal associations do not imply causation: Temporal and atemporal mediation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhams, J., & Horvath, M. (2013). Introduction. In M. Horvath, & J. Woodhams (Eds.), Handbook on the study of multiple perpetrator rape: A multidisciplinary response to an international problem (pp. 1–9). Routledge. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- World Population Review. (2025). Rape statistics by country. Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/rape-statistics-by-country#:~:text=Some%20countries%20count%20each%20individual,minus%20the%20victim%20or%20victims (accessed on 10 June 2025).[Green Version]

| One Defendant | Three Defendants | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intoxicated | Sober | Intoxicated | Sober | |||||||||||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Verdict | 0.37 | 0.49 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.45 | 0.51 | 0.48 | 0.51 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.48 |

| Victim | ||||||||||||||||

| Credibility | 4.48 | 1.60 | 4.66 | 1.73 | 4.67 | 1.71 | 4.83 | 1.96 | 4.42 | 1.54 | 5.15 | 1.25 | 4.89 | 1.56 | 5.67 | 1.35 |

| Blame | 3.02 | 1.70 | 3.13 | 1.90 | 2.71 | 1.46 | 2.53 | 1.72 | 3.81 | 1.32 | 2.65 | 1.87 | 3.29 | 1.97 | 2.06 | 1.69 |

| Communicate | 4.53 | 1.66 | 4.00 | 2.08 | 5.95 | 1.43 | 5.80 | 1.77 | 4.05 | 1.60 | 3.53 | 1.70 | 6.14 | 1.46 | 5.67 | 1.58 |

| Consent | 3.90 | 1.97 | 3.05 | 2.09 | 5.68 | 1.63 | 5.75 | 1.97 | 3.55 | 1.54 | 2.71 | 1.90 | 5.10 | 1.95 | 4.92 | 2.08 |

| Helplessness | 4.57 | 1.72 | 5.53 | 1.31 | 3.16 | 1.83 | 3.35 | 2.18 | 5.38 | 1.47 | 5.82 | 1.01 | 3.86 | 1.93 | 4.92 | 1.82 |

| Sympathy | 4.63 | 2.08 | 4.89 | 2.31 | 4.74 | 1.82 | 4.95 | 1.88 | 4.62 | 1.53 | 5.47 | 1.97 | 4.52 | 2.02 | 5.46 | 1.93 |

| Anger | 1.97 | 1.50 | 1.79 | 1.36 | 2.53 | 1.54 | 1.90 | 1.25 | 3.10 | 1.79 | 2.29 | 1.86 | 2.24 | 1.79 | 1.50 | 1.44 |

| Intoxication | 6.40 | 1.25 | 6.79 | 0.54 | 1.47 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 6.57 | 0.60 | 6.65 | 0.70 | 1.24 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 0.41 |

| Defendant | ||||||||||||||||

| Credibility | 4.13 | 1.63 | 4.28 | 1.76 | 3.89 | 1.44 | 4.00 | 1.75 | 3.65 | 1.86 | 2.97 | 1.56 | 3.17 | 1.81 | 2.60 | 1.57 |

| Blame | 5.13 | 1.66 | 4.47 | 2.04 | 4.71 | 1.80 | 5.10 | 1.66 | 4.81 | 1.82 | 5.91 | 1.51 | 5.06 | 1.74 | 5.74 | 1.23 |

| Force | 3.53 | 1.94 | 3.21 | 1.44 | 3.84 | 1.92 | 3.95 | 2.24 | 3.19 | 1.82 | 4.08 | 1.95 | 3.70 | 1.81 | 4.53 | 2.04 |

| Vulnerability | 4.33 | 2.02 | 4.89 | 1.82 | 3.26 | 1.37 | 3.90 | 2.05 | 4.29 | 1.91 | 5.49 | 1.85 | 3.37 | 2.15 | 3.67 | 2.05 |

| Sympathy | 2.97 | 1.85 | 3.26 | 1.82 | 3.16 | 1.68 | 2.95 | 1.82 | 2.76 | 1.57 | 1.73 | 1.41 | 2.43 | 1.56 | 1.99 | 1.72 |

| Anger | 3.57 | 2.18 | 4.26 | 2.31 | 4.26 | 1.91 | 4.05 | 2.28 | 3.46 | 2.32 | 5.63 | 1.93 | 4.84 | 1.98 | 4.92 | 2.26 |

| Intoxication | 2.60 | 2.58 | 2.42 | 2.52 | 1.63 | 1.30 | 1.15 | 0.67 | 1.14 | 0.48 | 1.53 | 1.17 | 1.43 | 1.18 | 1.17 | 0.56 |

| B | SE | p | Wald | OR | Nagelkerke R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Verdict | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.01 | |||||

| Gender | −0.35 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 1.33 | 0.70 | |

| Step 2 | 0.10 | |||||

| Gender | −0.30 | 0.32 | 0.35 | 0.87 | 0.74 | |

| Defendant Number | 1.05 | 0.32 | <0.001 | 10.84 | 2.86 | |

| Victim Intoxication | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.55 | 1.27 | |

| Victim Ratings | ||||||

| B | SE | p | R2 | ΔR2 | p | |

| Credibility | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | |||

| Gender | −0.50 | 0.25 | 0.04 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.12 | |||

| Gender | −0.45 | 0.25 | 0.07 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.35 | 0.24 | 0.15 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | 0.33 | 0.25 | 0.18 | |||

| Blame | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |||

| Gender | 0.64 | 0.26 | 0.02 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.18 | |||

| Gender | 0.60 | 0.27 | 0.03 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.15 | 0.26 | 0.58 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | −0.49 | 0.27 | 0.07 | |||

| Communication | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.41 | |||

| Gender | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.41 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.24 | 0.24 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.09 | |||

| Defendant Number | −0.23 | 0.25 | 0.36 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | 1.85 | 0.26 | <0.001 | |||

| Consent | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 | |||

| Gender | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.23 | 0.23 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.13 | |||

| Defendant Number | −0.54 | 0.29 | 0.07 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | 2.04 | 0.29 | <0.001 | |||

| Helplessness | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | |||

| Gender | −0.57 | 0.29 | 0.06 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.21 | 0.19 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | −0.69 | 0.26 | 0.01 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.87 | 0.26 | 0.001 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | −1.50 | 0.26 | <0.001 | |||

| Sympathy | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | |||

| Gender | −0.57 | 0.30 | 0.06 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.80 | |||

| Gender | −0.56 | 0.30 | 0.06 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.51 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.98 | |||

| Anger | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |||

| Gender | 0.57 | 0.24 | 0.02 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.40 | |||

| Gender | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.02 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.27 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | −0.22 | 0.25 | 0.38 | |||

| Defendant Ratings | ||||||

| B | SE | p | R2 | ΔR2 | p | |

| Credibility | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.23 | |||

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Gender | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.23 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.10 | 0.09 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.37 | |||

| Defendant Number | −0.95 | 0.26 | <0.001 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | −0.33 | 0.26 | 0.21 | |||

| Blame | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16 | |||

| Gender | −0.36 | 0.26 | 0.16 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.21 | |||

| Gender | −0.34 | 0.26 | 0.20 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.45 | 0.26 | 0.08 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | 0.04 | 0.26 | 0.88 | |||

| Force Used | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16 | |||

| Gender | −0.42 | 0.29 | 0.16 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.19 | |||

| Gender | −0.35 | 0.29 | 0.23 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.50 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.10 | |||

| Victim’s Vulnerability | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.09 | |||

| Gender | −0.53 | 0.31 | 0.09 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.10 | 0.08 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | −0.66 | 0.30 | 0.03 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.08 | 0.30 | 0.79 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | −1.20 | 0.30 | <0.001 | |||

| Sympathy | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.18 | |||

| Gender | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.18 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.01 | |||

| Gender | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.23 | |||

| Defendant Number | −0.81 | 0.26 | <0.001 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | −0.03 | 0.26 | 0.90 | |||

| Anger | ||||||

| Step 1 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.04 | |||

| Gender | −0.71 | 0.34 | 0.04 | |||

| Step 2 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.09 | |||

| Gender | −0.65 | 0.34 | 0.06 | |||

| Defendant Number | 0.63 | 0.34 | 0.06 | |||

| Victim Intoxication | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.35 | |||

| Direct Effect | Effect | SE | 95% CI a |

| −1.20 | 0.68 | −2.53, 0.13 | |

| Indirect Effects | Effect | SE | 95% CI |

| Victim Credibility | 0.21 | 0.13 | −0.04, 0.47 |

| Defendant Credibility | 0.53 | 0.13 | 0.27, 0.79 |

| Victim Blame | −0.01 | 0.11 | −0.21, 0.20 |

| Defendant Blame | 0.22 | 0.12 | −0.02, 0.46 |

| Victim Sympathy | 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.11, 0.26 |

| Defendant Sympathy | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.14, 0.60 |

| Victim Anger | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.14, 0.07 |

| Defendant Anger | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.02, 0.46 |

| Victim Helplessness | 0.24 | 0.10 | 0.05, 0.42 |

| Victim Consent | 0.08 | 0.08 | −0.07, 0.23 |

| Total | 0.72 | 0.20 | 0.33, 1.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Burke, K.C.; Golding, J.M.; Neuschatz, J.; Geoghagan, L. Perceptions of Multiple Perpetrator Rape in the Courtroom. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070844

Burke KC, Golding JM, Neuschatz J, Geoghagan L. Perceptions of Multiple Perpetrator Rape in the Courtroom. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(7):844. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070844

Chicago/Turabian StyleBurke, Kelly C., Jonathan M. Golding, Jeffrey Neuschatz, and Libbi Geoghagan. 2025. "Perceptions of Multiple Perpetrator Rape in the Courtroom" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 7: 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070844

APA StyleBurke, K. C., Golding, J. M., Neuschatz, J., & Geoghagan, L. (2025). Perceptions of Multiple Perpetrator Rape in the Courtroom. Behavioral Sciences, 15(7), 844. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15070844