A Network Analysis of Health Care Access and Behavioral/Mental Health in Hispanic Children and Adolescents

Abstract

1. Introduction

Child Healthcare and Behavioral/Mental Health

2. Method

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Child Identification Section (CID)

2.3.2. Child Health Care Access and Utilization Section (CAU)

2.3.3. Behavioral and Mental Health (BMH)

2.3.4. Stressful Life Events (SLEs)

3. Analysis

3.1. Centrality

3.2. Stability

4. Results

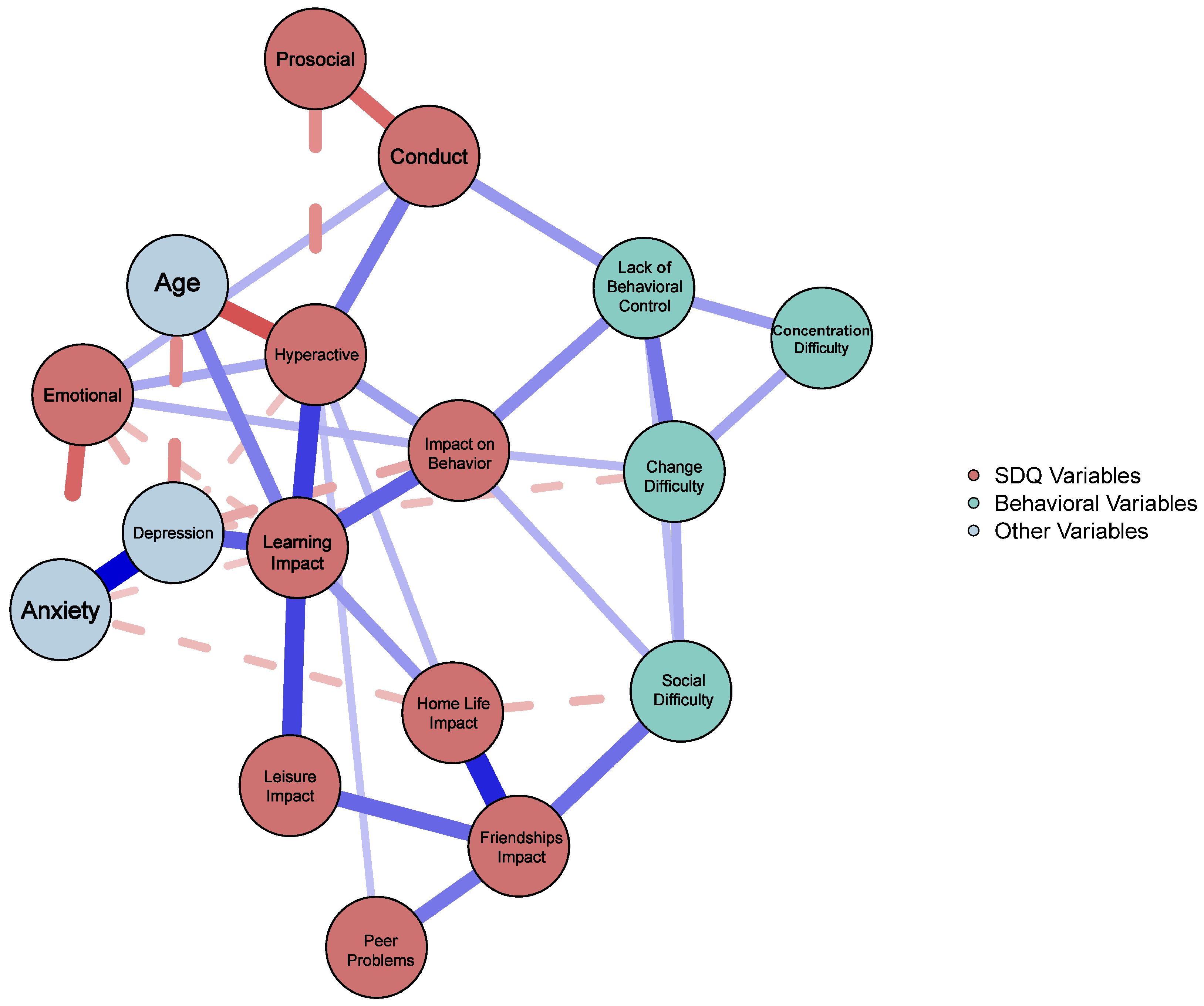

4.1. Hispanic Child Network

4.2. Network Accuracy and Stability

5. Discussion

5.1. Hispanic Child Network

5.2. Limitations, Strengths, and Future Directions

5.3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Hispanic and Latina/o are used interchangeably to refer to Latin Americans and/or individuals who speak Spanish. In efforts to stay consistent with the term from the parent study, we kept the term Hispanic instead of using Latina/o or Latinx to describe the population. However, when using Hispanic, we recognize and honor the gender-expansive (i.e., Latinx) and Afro-Latin individuals who are also a part of the Hispanic/Latinx communities. See Cardemil et al. (2019) for more information. |

References

- Alcalá, H. E., Chen, J., Langellier, B. A., Roby, D. H., & Ortega, A. N. (2017). Impact of the affordable care act on health care access and utilization among latinos. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 30(1), 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, M., O’Malley, I. S., DiMarzio, K., & Zhen-Duan, J. (2022). Framework for understanding and addressing racial and ethnic disparities in children’s mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 31(2), 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, M., Vallas, M., & Pumariega, A. J. (2010). Racial and ethnic disparities in pediatric mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics, 19(4), 759–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, M. L., Elliott, M. N., Fuligni, A. J., Morales, L. S., Hambarsoomian, K., & Schuster, M. A. (2008). The relationship between Spanish language use and substance use behaviors among Latino youth: A social network approach. Journal of Adolescent Health, 43(4), 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E. R., & Mayes, L. C. (2010). Race/ethnicity and internalizing disorders in youth: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(3), 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andraska, E. A., Alabi, O., Dorsey, C., Erben, Y., Velazquez, G., Franco-Mesa, C., & Sachdev, U. (2021). Health care disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Seminars in Vascular Surgery, 34(3), 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bámaca-Colbert, M. Y., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Gayles, J. G. (2012). A developmental-contextual model of depressive symptoms in Mexican-origin female adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 48(2), 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, J. M., Mountain, S., Telke, S., Trofholz, A., Lingras, K., Dwivedi, R., & Zak-Hunter, L. (2020). Stressful life events and associations with child and family emotional and behavioral well-being in diverse immigrant and refugee populations. Families, Systems, & Health, 38(4), 380. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsey, J., Cornelius, M., Jamal, A., Park-Lee, E., Cooper, M. R., Sawdey, M. D., Cullen, K. A., & Neff, L. (2023). Tobacco product use among U.S. middle and high school students—National youth tobacco survey, 2023. MMWR and Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 72(44), 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, C. C., & Sierra, L. A. (2021). Anti-immigrant rhetoric, deteriorating health access, and COVID-19 in the Rio Grande Valley, Texas. Health Security, 19(S1), S50–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, E. T., Moore, J. M., Vidmar, A. P., Chaves, E., Cason–Wilkerson, R., Novick, M. B., Fernandez, C., Tucker, J. M., & COMPASS (Childhood Obesity Multi-Program Analysis and Study System). (2024). Assessment of adverse childhood experiences and social determinants of health: A survey of practices in pediatric weight management programs. Childhood Obesity, 20(6), 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, L. (2007). Childhood adultification in economically disadvantaged families: A conceptual model. Family Relations, 56(4), 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, A. V., Chen, J., McKenna, R. M., & Ortega, A. N. (2019). Health care access and utilization among US immigrants before and after the Affordable Care Act. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(2), 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, E., Gutierrez, R., Schmitt, E., Castenada, J., Torres-Cacho, N., & Rodriguez, R. M. (2022). Impact of anti-immigrant rhetoric on Latinx families’ perceptions of child safety and health care access. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 62(2), 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardemil, E. V., Millán, F., & Aranda, E. (2019). A new, more inclusive name: The Journal of Latinx Psychology. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 7(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casseus, M. (2024). Racial and ethnic disparities in unmet need for mental health care among children: A nationally representative study. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 11(6), 3489–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A. R., & Slopen, N. (2024). Racial and ethnic disparities for unmet needs by mental health condition: 2016 to 2021. Pediatrics, 153(1), e2023062286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cipra, B. A. (1987). An introduction to the Ising model. The American Mathematical Monthly, 94(10), 937–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criss, M. M., Pettit, G. S., Bates, J. E., Dodge, K. A., & Lapp, A. L. (2002). Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children’s externalizing behavior: A longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child Development, 73(4), 1220–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, B. W., Still, S., LoParo, D., Aponte-Rivera, V., Johnson, B. N., Schneider, R. L., Nemeroff, C. B., Mayberg, H. S., & Craighead, W. E. (2020). Somatic symptoms in treatment-naïve Hispanic and non-Hispanic patients with major depression. Depression and Anxiety, 37(2), 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). QGraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2010). Applications of the lasso and grouped lasso to the estimation of sparse graphical models (pp. 1–22). Technical Report. Stanford University. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228839529_Applications_of_the_Lasso_and_grouped_Lasso_to_the_estimation_of_sparse_graphical_models (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Fuentes, L. S., Derlan Williams, C., León-Pérez, G., & Moreno, O. (2024). Latine immigrant youths’ attitudes toward mental health and mental health services and the role of culturally-responsive programming. Children and Youth Services Review, 163, 107795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, T., Venta, A., Moreno, O., Gudiño, O. G., & Mercado, A. (2024). Cultural stress is toxic stress: An expanded cultural stress theory model for understanding mental health risk in Latinx immigrant youth. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 30(4), 863–875. [Google Scholar]

- Garcini, L. M., Nguyen, K., Lucas-Marinelli, A., Moreno, O., & Cruz, P. L. (2022). “No one left behind”: A social determinant of health lens to the wellbeing of undocumented immigrants. Current Opinion in Psychology, 47, 101455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearing, R. E., Washburn, M., Brewer, K. B., Cabrera, A., Yu, M., & Torres, L. R. (2024). Pathways to mental health care: Latinos’ help-seeking preferences. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 12(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, N. A., Liu, Y., Jensen, M., Tein, J. Y., White, R. M., & Deardorff, J. (2017). Externalizing and internalizing pathways to Mexican American adolescents’ risk taking. Development and Psychopathology, 29(4), 1371–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, K. T., Newman, L. A., & Ward, P. R. (2014). Improving access to health information for older migrants by using grounded theory and social network analysis to understand their information behaviour and digital technology use. European Journal of Cancer Care, 23(6), 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5), 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R. (1999). The extended version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a guide to child psychiatric caseness and consequent burden. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 40(5), 791–799. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10433412/ (accessed on 22 August 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grassie, H. L., Kennedy, S. M., Halliday, E. R., Bainter, S. A., & Ehrenreich-May, J. (2022). Symptom-level networks of youth-and parent-reported depression and anxiety in a transdiagnostic clinical sample. Depression and Anxiety, 39(3), 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haerle, D. R. (2019). Unpacking adultification: Institutional experiences and misconduct of adult court and juvenile court youth living under the same roof. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 63(5), 663–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallquist, M. N., Wright, A. G., & Molenaar, P. C. (2021). Problems with centrality measures in psychopathology symptom networks: Why network psychometrics cannot escape psychometric theory. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hevey, D. (2018). Network analysis: A brief overview and tutorial. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 6(1), 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, S., Godoy, L., Beers, L. S., & Lewin, A. (2017). Improving mental health access for low-income children and families in the primary care setting. Pediatrics, 139(1), e20151175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holahan, J., O’Brien, C., & Dubay, L. (2025). Imposing per capita medicaid caps and reducing the affordable care act’s enhanced match: Impacts on federal and state medicaid spending 2026–35. Urban Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Isasi, C. R., Rastogi, D., & Molina, K. (2016). Health issues in Hispanic/Latino youth. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 4(2), 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K. F., Cunningham, P. D., Tirado, C., Moreno, O., Gillespie, N. N., Duyile, B., Hughes, D. C., Goodman Scott, E., & Brookover, D. (2023). Social determinants of mental health considerations for counseling children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 9(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, M. J., Williams, M. L., Fujimoto, K., Shrader, C. H., Schneider, J., & de La Rosa, M. (2019). A social network analysis of cooperation and support in an HIV service delivery network for young Latino MSM in Miami. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(6), 887–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyce, D. W., West, S. J., Perrin, P. B., Agtarap, S. D., Finn, J. A., Juengst, S. B., Dams-O’Connor, K., Eagye, C. B., Vargas, T. A., Chung, J. S., & Bombardier, C. H. (2021). Network analysis of neurobehavioral and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms one year after traumatic brain injury: A veterans affairs traumatic brain injury model systems study. Journal of Neurotrauma, 38(23), 3332–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuperminc, G. P., Wilkins, N. J., Jurkovic, G. J., & Perilla, J. L. (2013). Filial responsibility, perceived fairness, and psychological functioning of Latino youth from immigrant families. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(2), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langellier, B. A., Chen, J., Vargas-Bustamante, A., Inkelas, M., & Ortega, A. N. (2016). Understanding health-care access and utilization disparities among Latino children in the United States. Journal of Child Health Care, 20(2), 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauritzen, S. L. (1996). Graphical models (Vol. 17). Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leath, S., Mathews, C., Harrison, A., & Chavous, T. (2019). Racial identity, racial discrimination, and classroom engagement outcomes among Black girls and boys in predominantly Black and predominantly White school districts. American Educational Research Journal, 56(4), 1318–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. D., & Hastie, T. J. (2015). Learning the structure of mixed graphical models. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 24(1), 230–253. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/43304940 (accessed on 22 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, F. S., Baidal, J. A. W., Fernández, C. R., & Flores, G. (2024). Bias, prejudice, discrimination, racism, and social determinants: The impact on the health and well-being of Latino children and youth. Academic Pediatrics, 24(7), S196–S203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swendsen, J., Avenevoli, S., Case, B., Georgiades, K., Heaton, L., Swanson, S., & Olfson, M. (2011). Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in US adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50(1), 32–45. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, O., & Cardemil, E. (2013). Religiosity and mental health services: An exploratory study of help-seeking among Latinos. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1(1), 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, O., Fuentes, L., Garcia-Rodriguez, I., Corona, R., & Cadenas, G. A. (2021). Psychological impact, strengths, and handling the uncertainty among latinx DACA recipients. The Counseling Psychologist, 49(5), 728–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, O., Tirado, C., Garcia-Rodriguez, I., Muñoz, G., Gomez Giuliani, N., & Cadenas, G. (2024). The intersection of immigration-related racism and xenophobia shaping undocumented immigrants’ experiences with liminality. Qualitative Psychology. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Health Statistics. (2020). National Health Interview Survey, 2019. Public-use data file and documentation. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm (accessed on 22 August 2024).

- Neiman, P. U., Tsai, T. C., Bergmark, R. W., Ibrahim, A., Nathan, H., & Scott, J. W. (2021). The affordable care act at 10 years: Evaluating the evidence and navigating an uncertain future. Journal of Surgical Research, 263, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K. (2025). Lawmakers consider massive Medicaid cuts. Psychiatric News, 60(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okine, L., & Unger, J. B. (2024). Substance use among Latinx youth: The roles of sociocultural influences, family factors, and childhood adversity. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 34(4), 1562–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opsahl, T., Agneessens, F., & Skvoretz, J. (2010). Node centrality in weighted networks: Generalizing degree and shortest paths. Social Networks, 32(3), 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormiston, C. K., Chiangong, J., & Williams, F. (2023). The COVID-19 pandemic and Hispanic/Latina/o immigrant mental health: Why more needs to be done. Health Equity, 7(1), 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornelas, C., Torres, J. M., Torres, J. R., Alter, H., Taira, B. R., & Rodriguez, R. M. (2021). Anti-immigrant rhetoric and the experiences of Latino immigrants in the emergency department. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 22(3), 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, A. N., McKenna, R. M., Chen, J., Alcalá, H. E., Langellier, B. A., & Roby, D. H. (2018). Insurance coverage and well-child visits improved for youth under the Affordable Care Act, but Latino youth still lag behind. Academic Pediatrics, 18(1), 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, K. B., Holt, M. K., Green, J. G., Porche, M. V., Koenig, B., & Xuan, Z. (2022). Time trends and disparities in anxiety among adolescents, 2012–2018. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(1), 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, E. (2016). The nation’s Latino population is defined by its youth. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2016/04/20/the-nations-latino-population-is-defined-by-its-youth/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Perez-Escamilla, R. (2010). Health care access among Latinos: Implications for social and health care reforms. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 9(1), 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez García, J. I. (2019). Integrating Latina/o ethnic determinants of health in research to promote population health and reduce health disparities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Reardon, T., Harvey, K., Baranowska, M., O’brien, D., Smith, L., & Creswell, C. (2017). What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 623–647. [Google Scholar]

- Rhemtulla, M., Fried, E. I., Aggen, S. H., Tuerlinckx, F., Kendler, K. S., & Borsboom, D. (2016). Network analysis of substance abuse and dependence symptoms. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 161, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D. J., Hoekstra, R. H., Toner, E. R., & Borsboom, D. (2020). The network approach to psychopathology: A review of the literature 2008–2018 and an agenda for future research. Psychological Medicine, 50(3), 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas Perez, O. F., Silva, M. A., Galvan, T., Moreno, O., Venta, A., Garcini, L., & Paris, M. (2023). Buscando la calma dentro de la tormenta: A brief review of the recent literature on the impact of anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies on stress among Latinx immigrants. Chronic Stress, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, A., Williams, C. D., Winter, M., Sullivan, T., Dejus Elias, M., & Moreno, O. (2023). A scoping review of barriers and facilitators to Latinx caregivers’ help-seeking for their children’s mental health symptoms and disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32, 3908–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., Pettit, G. S., & Bates, J. E. (2000). Friendship as a moderating factor in the pathway between early harsh home environment and later victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology, 36(5), 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slopen, N., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Shonkoff, J. P., Carle, A. C., & Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2023). State-level anti-immigrant sentiment and policies and health risks in US Latino children. Pediatrics, 152(3), e2022057581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, G. L., Gonzalez, L. M., Cupito, A. M., Kiang, L., & Supple, A. J. (2015). The protective role of familism in the lives of Latino adolescents. Journal of Family Issues, 36(10), 1255–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, B. B., Jones, J. R., Ghandour, R. M., Kogan, M. D., & Newacheck, P. W. (2011). The medical home: Health care access and impact for children and youth in the United States. Pediatrics, 127(4), 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2024). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. (HHS Publication No. PEP24-07-021, NSDUH Series H-59). Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2023-nsduh-annual-national-report (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Tesfaye, S., Cronin, R. M., Lopez-Class, M., Chen, Q., Foster, C. S., Gu, C. A., Guide, A., Hiatt, R. A., Johnson, A. S., Joseph, C. L. M., Khatri, P., Lim, S., Litwin, T. R., Munoz, F. A., Ramirez, A. H., Sansbury, H., Schlundt, D. G., Viera, E. N., Dede-Yildirim, E., & Clark, C. R. (2024). Measuring social determinants of health in the All of Us Research Program. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 8815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 58(1), 267–288. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2346178 (accessed on 22 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Turner, E. A., Jensen-Doss, A., & Heffer, R. W. (2015). Ethnicity as a moderator of how parents’ attitudes and perceived stigma influence intentions to seek child mental health services. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(4), 613. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. (2021). Racial and ethnic diversity in the United States: 2010 census and 2020 census. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/racial-and-ethnic-diversity-in-the-united-states-2010-and-2020-census.html (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- Valdivieso-Mora, E., Peet, C. L., Garnier-Villarreal, M., Salazar-Villanea, M., & Johnson, D. K. (2016). A systematic review of the relationship between familism and mental health outcomes in Latino population. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsdorf, A. A., Caughy, M. O. B., Osborne, K. R., Valdez, C. R., King, V. A., & Owen, M. T. (2024). Acculturation stress magnifies child depression effect of stressful life events for Latinx youth 3 years later. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 12(2), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X., Jiang, L., Barry, L., Zhang, X., Vasilenko, S. A., & Heath, R. D. (2024). A scoping review on adverse childhood experiences studies using latent class analysis: Strengths and challenges. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 25(2), 1695–1708. [Google Scholar]

- West, A. E., Conn, B. M., Lindquist, E. G., & Dews, A. A. (2023). Dismantling structural racism in child and adolescent psychology: A call to action to transform healthcare, education, child welfare, and the psychology workforce to effectively promote BIPOC youth health and development. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 52(3), 427–446. [Google Scholar]

- West, S. J., & Chester, D. S. (2021). The tangled webs we wreak: Examining the structure of aggressive personality using psychometric networks. Journal of Personality, 90(5), 762–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | Min | Max | Skew | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10.99 | 4.05 | 4 | 17 | −0.19 | −1.19 |

| Anxiety | 4.33 | 1.12 | 1 | 5 | −1.76 | 2.09 |

| Change Difficulty | 1.21 | 0.51 | 1 | 4 | 2.63 | 7.19 |

| Concentration Difficulty | 1.10 | 0.39 | 1 | 4 | 4.43 | 21.87 |

| Conduct | 0.86 | 1.32 | 0 | 9 | 2.03 | 5.00 |

| Depression | 4.64 | 0.83 | 1 | 5 | −2.69 | 7.07 |

| Emotional | 1.22 | 1.72 | 0 | 10 | 1.87 | 3.81 |

| Friendships Impact | 1.56 | 0.83 | 1 | 4 | 1.41 | 1.16 |

| Home Life Impact | 1.73 | 0.86 | 1 | 4 | 0.98 | 0.13 |

| Hyperactive | 2.05 | 2.32 | 0 | 10 | 1.33 | 1.36 |

| Impact on Behavior | 1.29 | 0.59 | 1 | 4 | 2.21 | 5.08 |

| Lack Behavioral Control | 1.18 | 0.50 | 1 | 4 | 3.29 | 11.89 |

| Learning Impact | 2.07 | 1.08 | 1 | 4 | 0.56 | −1.03 |

| Leisure Impact | 1.46 | 0.79 | 1 | 4 | 1.73 | 2.20 |

| Peer Problems | 1.26 | 1.54 | 0 | 10 | 1.60 | 3.24 |

| Prosocial | 8.91 | 1.72 | 0 | 10 | −2.11 | 5.18 |

| Social Difficulty | 1.12 | 0.41 | 1 | 4 | 4.03 | 18.26 |

| Node | Betweenness | Closeness | Strength | Expected Influence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prosocial | 0 | 0.005 | 0.41 | −0.41 |

| Peer | 2 | 0.005 | 0.58 | 0.58 |

| Hyper | 16 | 0.007 | 1.51 | 0.58 |

| Conduct | 14 | 0.006 | 0.83 | 0.45 |

| Emotionality | 4 | 0.005 | 0.97 | 0.11 |

| Age | 0 | 0.006 | 0.62 | −0.24 |

| Leisure | 10 | 0.006 | 0.61 | 0.39 |

| Classroom | 24 | 0.007 | 1.58 | 1.18 |

| Friendships | 14 | 0.006 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| HomeLife | 2 | 0.005 | 0.81 | 0.37 |

| Diff_EmoBeh | 13 | 0.006 | 1.02 | 0.75 |

| MakeFriends | 6 | 0.005 | 0.67 | 0.45 |

| ChangeRoutine | 5 | 0.005 | 0.69 | 0.48 |

| Concentration | 0 | 0.004 | 0.29 | 0.29 |

| Control | 12 | 0.005 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| Depression | 10 | 0.006 | 1.23 | 0.02 |

| Anxiety | 4 | 0.005 | 0.80 | −0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garcia-Rodriguez, I.; West, S.J.; Tirado, C.; Hernandez Castro, C.; Fuentes, L.; Perrin, P.B.; Moreno, O.A. A Network Analysis of Health Care Access and Behavioral/Mental Health in Hispanic Children and Adolescents. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060826

Garcia-Rodriguez I, West SJ, Tirado C, Hernandez Castro C, Fuentes L, Perrin PB, Moreno OA. A Network Analysis of Health Care Access and Behavioral/Mental Health in Hispanic Children and Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):826. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060826

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcia-Rodriguez, Isis, Samuel J. West, Camila Tirado, Cindy Hernandez Castro, Lisa Fuentes, Paul B. Perrin, and Oswaldo A. Moreno. 2025. "A Network Analysis of Health Care Access and Behavioral/Mental Health in Hispanic Children and Adolescents" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060826

APA StyleGarcia-Rodriguez, I., West, S. J., Tirado, C., Hernandez Castro, C., Fuentes, L., Perrin, P. B., & Moreno, O. A. (2025). A Network Analysis of Health Care Access and Behavioral/Mental Health in Hispanic Children and Adolescents. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060826