How Autonomy Support Sustains Emotional Engagement in College Physical Education: A Longitudinal Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Autonomy Support and Emotional Engagement in Physical Education

2.2. Mediating Role of Self-Acceptance

2.3. Mediating Role of Academic Self-Efficacy

2.4. The Chain Mediation Effect of Self-Acceptance and Academic Self-Efficacy

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurement Subjects

3.2. Research Tools

3.2.1. Autonomous Support Questionnaires

3.2.2. Self-Acceptance Questionnaire

3.2.3. Academic Self-Efficacy Questionnaire

3.2.4. Sports Learning Emotional Engagement Questionnaire

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Reliability and Validity Testing

4.2. Common Method Bias Test

4.3. Longitudinal Measurement Invariance Test

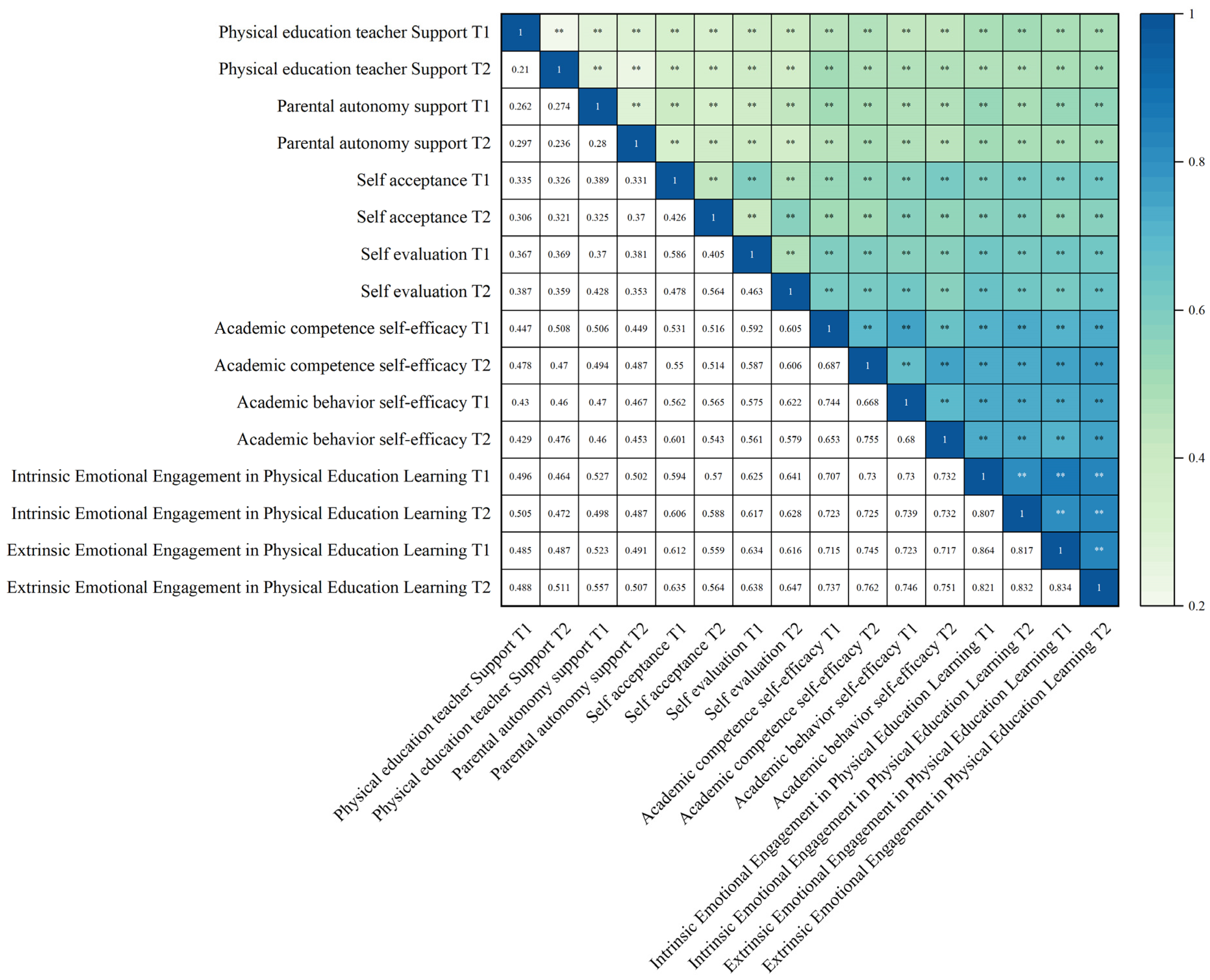

4.4. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

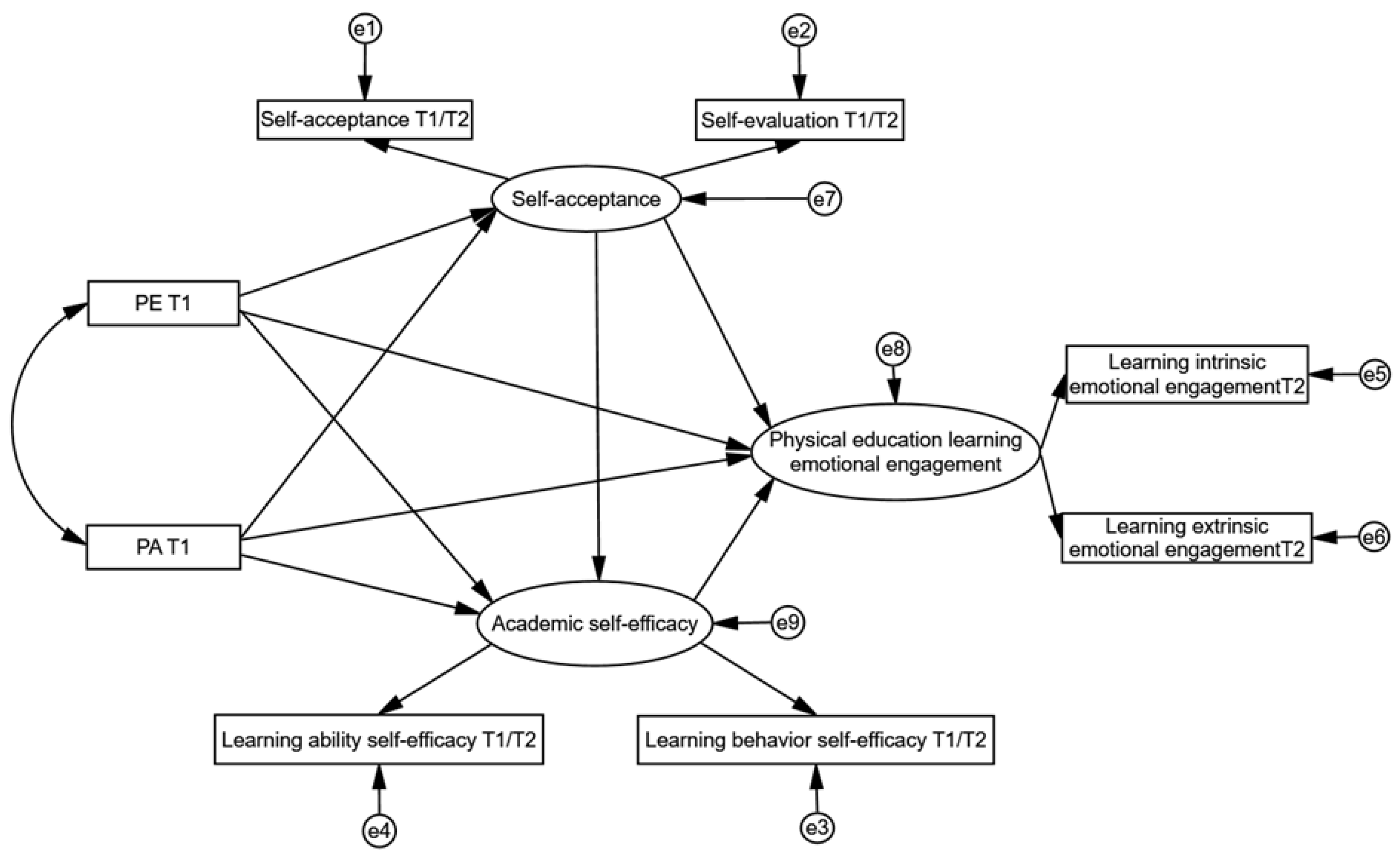

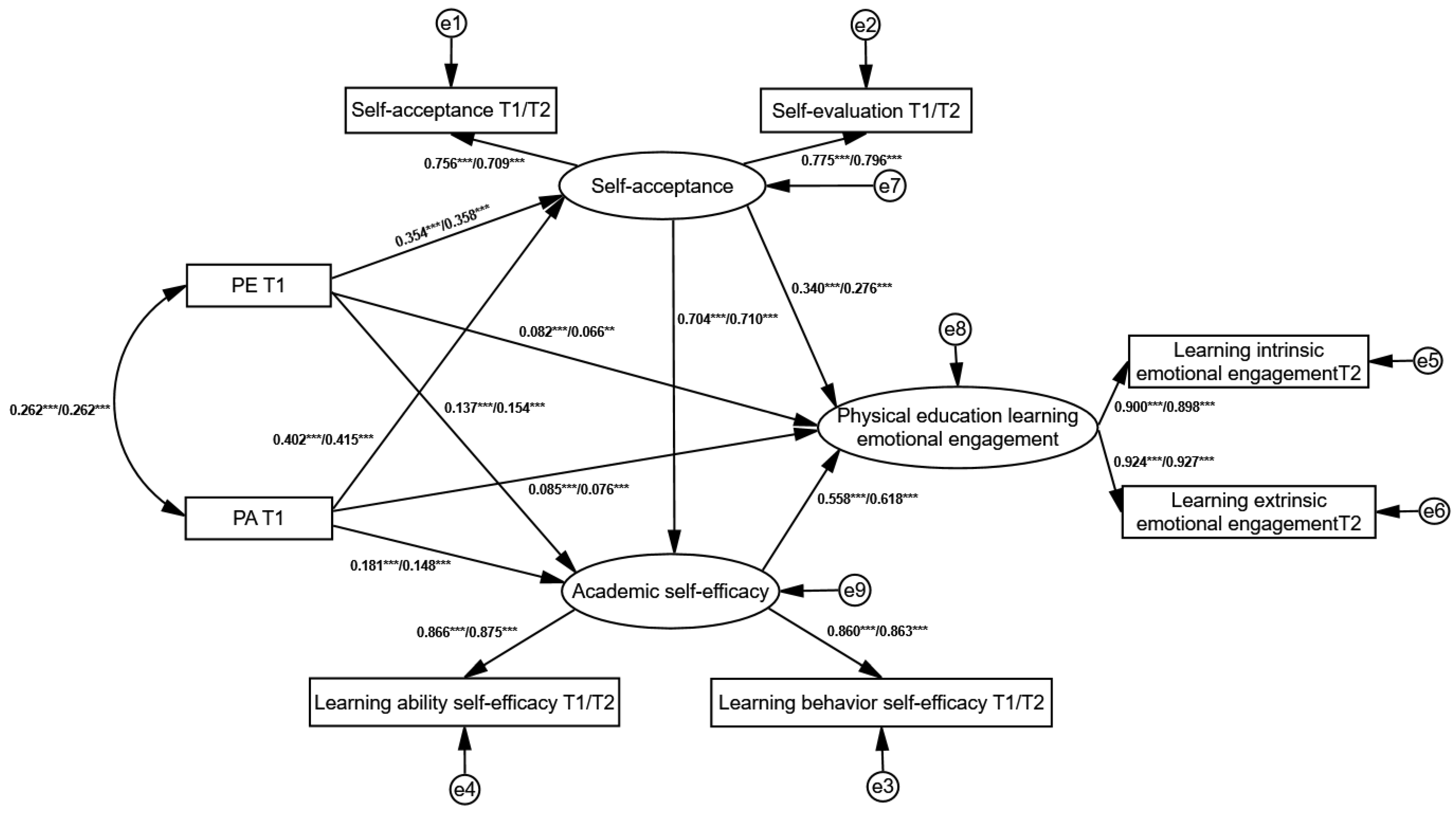

4.5. Longitudinal Mediation Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Appleton, J. J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the Student Engagement Instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arik, A., & Erturan, G. (2023). Autonomy Support and Motivation in Physical Education: A Comparison of Teacher and Student Perspectives. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 10(3), 649–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action (pp. 23–28). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Baños, R., Calleja-Núñez, J. J., Espinoza-Gutiérrez, R., & Granero-Gallegos, A. (2023). Mediation of academic self-efficacy between emotional intelligence and academic engagement in physical education undergraduate students. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1178500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baños, R., Fuentesal, J., Conte, L., Ortiz-Camacho, M. D. M., & Zamarripa, J. (2020). Satisfaction, enjoyment and boredom with physical education as mediator between autonomy support and academic performance in physical education. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(23), 8898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, M., Steca, P., Fave, A. D., & Caprara, G. V. (2007). Academic self-efficacy beliefs and quality of experience in learning. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevans, K., Fitzpatrick, L. A., Sanchez, B., & Forrest, C. B. (2010). Individual and instructional determinants of student engagement in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 29(4), 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carson, S. H., & Langer, E. J. (2006). Mindfulness and self-acceptance. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 24, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrov, V., & Ran, R. (2001). Parent and teacher autonomy support in Russian and US adolescents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, Z., & Gao, W. F. (1999). The development of self-acceptance questionnaire and the test of its reliability and validity. Chinese Journal of Behavioral Medical Science, 8(1), 20–22. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=i12nDYUbXpJIIqRB6UHVNXzgkpw53wXK1ezncrd5OqMe5Bc3EbNkdzRCMCDDZJYspNApNbTV42C7N1iKIhi5jwXeoe6JEI7GM0JcW0eYQeBTjgICKMLRqUrqlR-ibD7O2SFwruufm-I7oJXFM8J4i8EmFZudwEKmVbpVirBMs-2ZJ1gdEZkW66fl6LHLoJDI&uniplatform=NZKPT (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Connell, J. P. (1991). Competence, autonomy and relatedness: A motivational analysis of self-system processes. In Minnesota symposium on child psychology (Vol. 2). Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. (1996). The learning climate questionnaire (LCQ). Available online: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/learning-climate-questionnaire/ (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 19(2), 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Muynck, G. J., Morbée, S., Soenens, B., Haerens, L., Vermeulen, O., Vande Broek, G., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2021). Do both coaches and parents contribute to youth soccer players’ motivation and engagement? An examination of their unique (de) motivating roles. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(5), 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobersek, U., & Arellano, D. L. (2017). Investigating the relationship between emotional intelligence, involvement in collegiate sport, and academic performance. The Sport Journal, 24(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, D., & Burden, R. (2020). What effect on learning does increasing the proportion of curriculum time allocated to physical education have? A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Physical Education Review, 26(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W., & Williams, C. M. (2010). The effects of parental involvement on students’ academic self-efficacy, engagement and intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology, 30(1), 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiring, C., & Taska, L. S. (1996). Family self-concept: Ideas on its meaning. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1995-98972-008 (accessed on 11 May 2025).

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J. A., & McColskey, W. (2012). The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 763–782). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garn, A. C., Simonton, K., Dasingert, T., & Simonton, A. (2017). Predicting changes in student engagement in university physical education: Application of control-value theory of achievement emotions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 29, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, M. M., McElvany, N., Bos, W., Köller, O., & Schöber, C. (2020). Determinants of academic self-efficacy in different socialization contexts: Investigating the relationship between students’ academic self-efficacy and its sources in different contexts. Social Psychology of Education, 23(2), 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillet, N., Vallerand, R. J., & Lafrenière, M. A. K. (2012). Intrinsic and extrinsic school motivation as a function of age: The mediating role of autonomy support. Social Psychology of Education, 15, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, S., & De Guise, A. A. (2024). Effects of the Learning how to motivate training on pupils’ motivation and engagement during pre-service physical education teachers’ internship. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 9, p. 1397043). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, L., Alivernini, F., Lucidi, F., Cozzolino, M., Savarese, G., Sibilio, M., & Salvatore, S. (2018). Autonomy supportive contexts, autonomous motivation, and self-efficacy predict academic adjustment of first-year university students. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 3, p. 95). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjaka, M., Tessitore, A., Blondel, L., Bozzano, E., Burlot, F., Debois, N., Delon, D., Figueiredo, A., Foerster, J., Gonçalves, C., Guidotti, F., Pesce, C., Pišl, A., Rheinisch, E., Rolo, A., Ryan, G., Templet, A., Varga, K., Warrington, G., … Doupona, M. (2021). Understanding the educational needs of parenting athletes involved in sport and education: The parents’ view. PLoS ONE, 16(1), e0243354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Großmann, N., & Wilde, M. (2019). Experimentation in biology lessons: Guided discovery through incremental scaffolds. International Journal of Science Education, 41(6), 759–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. (2018). The composition of emotional engagement in English learning and its role mechanism on learning achievement. Modern Foreign Language, 41(1), 55–65+146. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=4d8R2eTuy_l_lv7LD8_dueAjzqLu5H7Cnb-xN8z255XnoRIl0DN2wSG08gUkYMq-mqNjK7kmyKurm5B7FI1Yj2Zlj8kr13-DeCi9v51Mal8G083kKjRrVxZPUk0Uh5pyVvFD3ZuFMg06uPRQpyNgsg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Guo, Q., Samsudin, S., Ramlan, M. A., Lin, X., & Yuan, Y. (2024). Effect of teacher autonomy support on college students’ autonomous motivation in physical education: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Revista de Psicología del Deporte (Journal of Sport Psychology), 33(3), 433–442. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, M., & Tomás, J. M. (2019). The role of perceived autonomy support in predicting university students’ academic success mediated by academic self-efficacy and school engagement. Educational Psychology, 39(6), 729–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94(3), 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., Vitta, J. P., & Wu, J. (2024). Engagement in language learning: A systematic review of 20 years of research methods and definitions. Language Teaching Research, 28(1), 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. T., & Li, Y. (2001). Exploratory research on self-supporting of university students. Psychological Science, 24, 389–392. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, S. S., Niles, B. L., & Park, C. L. (2010). A mindfulness model of affect regulation and depressive symptoms: Positive emotions, mood regulation expectancies, and self-acceptance as regulatory mechanisms. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(6), 645–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanakia, P., & Bhansali, N. (2024). The relationship between psychological wellbeing, perceived parental autonomy support & empathy amongst outstation Indian college students. International Journal of Indian Psychology, 12(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H. (2018). Teachers’ autonomy support, autonomy suppression and conditional negative regard as predictors of optimal learning experience among high-achieving Bedouin students. Social Psychology of Education, 21, 223–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Christy, A. G., Schlegel, R. J., Donnellan, M. B., & Hicks, J. A. (2018). Existential ennui: Examining the reciprocal relationship between self-alienation and academic amotivation. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(7), 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisterer, S., & Paschold, E. (2022). Increased perceived autonomy-supportive teaching in physical education classes changes students’ positive emotional perception compared to controlling teaching. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1015362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, R. M., Kuhn, D., Siegler, R. S., Eisenberg, N., & Renninger, K. A. (Eds.). (2006). Handbook of child psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. (2023). A constraint-led approach: Enhancing skill acquisition and performance in sport and physical education pedagogy. Studies in Sports Science and Physical Education, 1(1), 1–10. Available online: https://www.pioneerpublisher.com/SSSPE/article/view/359 (accessed on 10 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Yu, P., Wu, J., & Guo, L. (2024). The influence of exercise adherence on peace of mind among Chinese college students: A moderated chain mediation model. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1447429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S., & Wang, J. (2015). The relationship between parenting style and social anxiety: The mediating role of self-acceptance. mediating role of social anxiety. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology, 23(6), 899–901. [Google Scholar]

- Mammadov, S., & Schroeder, K. (2023). A meta-analytic review of the relationships between autonomy support and positive learning outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 75, 102235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Cultural variation in the self-concept. In The self: Interdisciplinary approaches (pp. 18–48). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J., & Dowson, M. (2009). Interpersonal relationships, motivation, engagement, and achievement: Yields for theory, current issues, and educational practice. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 327–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, J. F. F., Neves, C. M., Morgado, F. F. D. R., Muzik, M., & Ferreira, M. E. C. (2021). Development and psychometric properties of the self-acceptance scales for pregnant and postpartum women. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 128(1), 258–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oga-Baldwin, W. Q., Fryer, L. K., Hiver, P., Al-Hoorie, A. H., & Mercer, S. (2021). Engagement growth in language learning classrooms: A latent growth analysis of engagement in Japanese elementary schools. In Student engagement in the language classroom (pp. 224–240). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Olivier, E., Archambault, I., De Clercq, M., & Galand, B. (2019). Student self-efficacy, classroom engagement, and academic achievement: Comparing three theoretical frameworks. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ommundsen, Y., & Kval⊘, S. E. (2007). Autonomy–Mastery, Supportive or Performance Focused? Different teacher behaviours and pupils’ outcomes in physical education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 51(4), 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y. H. (2014). Relationships among teachers’ self-efficacy and students’ motivation, atmosphere, and satisfaction in physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 33(1), 68–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How college affects students: Findings and insights from twenty years of research. Jossey-Bass Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Pastimo, O. F. A., & Muslikah, M. (2022). The relationship between self-acceptance and social support with self-confidence in Madrasah Tsanawiyah. Edukasi, 16(2), 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, D. E. (2017). Parental autonomy support and college student academic outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26, 2589–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. (2022). Parenting styles and self-acceptance of high school students: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. In 2022 international conference on science and technology ethics and human future (STEHF 2022) (pp. 39–43). Atlantis Press. Available online: https://www.atlantis-press.com/proceedings/stehf-22/125975569 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Perlman, D., & Webster, C. A. (2011). Supporting student autonomy in physical education. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 82(5), 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihu, M., & Hein, V. (2007). Autonomy support from physical education teachers, peers and parents among school students: Trans-contextual motivation model. Acta Kinesiologiae Universitatis Tartuensis, 12(1), 116–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y., & Ye, P. (2023). The influence of family socio-economic status on learning engagement of college students majoring in preschool education: The mediating role of parental autonomy support and the moderating effect of psychological capital. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1081608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (Eds.). (2022). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez Macias, M., Abad Robles, M. T., & Gimenez Fuentes-Guerra, F. J. (2021). Effects of sport teaching on Students’ enjoyment and fun: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 708155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, A. M. (2001). The peer group as a context for the development of young adolescent motivation and achievement. Child Development, 72(4), 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadoughi, M., & Hejazi, S. Y. (2021). Teacher support and academic engagement among EFL learners: The role of positive academic emotions. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, E., & Quirk, M. (2015). Getting students engaged might not be enough: The importance of psychological needs satisfaction on social-emotional and behavioral functioning among early adolescents. Social Psychology of Education, 18, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutz, P., & Lanehart, S. L. (2002). Introduction: Emotions in education. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweder, S. (2019). The role of control strategies, self-efficacy, and learning behavior in self-directed learning. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 7(Suppl. 1), 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C., Moss, A. C., & Chen, A. (2023). The expectancy-value theory: A meta-analysis of its application in physical education. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 12(1), 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B., McCaughtry, N., Martin, J., & Fahlman, M. (2009). Effects of teacher autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning in physical education. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 80(1), 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilenkova, L. N. (2020). Self-efficacy in the educational process. Journal of Modern Foreign Psychology, 9, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C. (2023). A review of the impact of individual self-acceptance and self-efficacy on academic achievement. Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies, 1(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanou, C. R., Perencevich, K. C., DiCintio, M., & Turner, J. C. (2004). Supporting autonomy in the classroom: Ways teachers encourage student decision making and ownership. Educational Psychologist, 39(2), 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q., Fang, X.-y., Hu, W., Chen, H.-d., Wu, M.-x., & Wang, F. (2013). The relationship between parent and teacher autonomy support and high school students’ development. Psychological Development and Education, 29(6), 604–615. Available online: https://devpsy.bnu.edu.cn/EN/Y2013/V29/I6/604 (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Toyota, H. (2011). Differences in relationship between emotional intelligence and self-acceptance as function of gender and Ibasho (a person who eases the mind) of Japanese undergraduates. Psihologijske Teme, 20(3), 449–459. Available online: https://hrcak.srce.hr/78736 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, A. C., Patall, E. A., Fong, C. J., Corrigan, A. S., & Pine, L. (2016). Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of research. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 605–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Pomerantz, E. M., & Chen, H. (2007). The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development, 78(5), 1592–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N., Ryan, W. S., DeHaan, C. R., Przybylski, A. K., Legate, N., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Parental autonomy support and discrepancies between implicit and explicit sexual identities: Dynamics of self-acceptance and defense. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. L., Bennie, A., Vasconcellos, D., Cinelli, R., Hilland, T., Owen, K. B., & Lonsdale, C. (2021). Self-determination theory in physical education: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedenman, E. M., Kruse-Diehr, A. J., Bice, M. R., McDaniel, J., Wallace, J. P., & Partridge, J. A. (2024). The role of sport participation on exercise self-efficacy, psychological need satisfaction, and resilience among college freshmen. Journal of American College Health, 72(9), 3507–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. C., & Lynn, S. J. (2010). Acceptance: An historical and conceptual review. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 30(1), 5–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, C. T., McKeown, I., Rothwell, M., Araújo, D., Robertson, S., & Davids, K. (2020). Sport practitioners as sport ecology designers: How ecological dynamics has progressively changed perceptions of skill “acquisition” in the sporting habitat. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C., Gu, Q., Deng, J., & Wang, X. (2022). Analysis on the factors and countermeasures restricting the transformation of college sports course. Forest Chemicals Review, 441–447. Available online: http://forestchemicalsreview.com/index.php/JFCR/article/view/1137 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Wu, C., Liu, X., Liu, J., Tao, Y., & Li, Y. (2024). Strengthening the meaning in life among college students: The role of self-acceptance and social support-evidence from a network analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1433609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, L. X., Li, J. C., Song, Y., & Hollon, S. D. (2013). Personal self-support traits and recognition of self-referent and other-referent information. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 41(10), 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C., Li, X., Wang, S., & Zhang, W. (2016). Teacher autonomy support reduces adolescent anxiety and depression: An 18-month longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zach, S., & Rosenblum, H. (2021). The affective domain—A program to foster social-emotional orientation in novice physical education teachers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T., Zhao, J., & Shen, B. (2024). The influence of perceived teacher and peer support on student engagement in physical education of Chinese middle school students: Mediating role of academic self-efficacy and positive emotions. Current Psychology, 43(12), 10776–10785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Yue, H., Sun, J., Liu, M., Li, C., & Bao, H. (2022). Regulatory emotional self-efficacy and psychological distress among medical students: Multiple mediating roles of interpersonal adaptation and self-acceptance. BMC Medical Education, 22(1), 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., & Long, L. (2004). Statistical test and control method of common method deviation. Advances in Psychological Science, 12, 942–950. Available online: https://journal.psych.ac.cn/adps/EN/Y2004/V12/I06/942 (accessed on 13 May 2025).

| Characteristic | Category | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 349 | 48.6% |

| Male | 369 | 51.4% | |

| Grade | Freshman | 230 | 32% |

| Sophomore | 232 | 32.3% | |

| Junior | 256 | 35.7% | |

| Household Registration | Rural | 248 | 34.5% |

| Urban | 470 | 65.5% | |

| Only Child | No | 261 | 36.4% |

| Yes | 457 | 63.6% | |

| Physical Education Major | No | 515 | 71.7% |

| Yes | 203 | 28.3% |

| Variable | Standardized Loadings | a | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Support | ||||

| PE Teacher Support (T1) | 0.953 | 0.956 | 0.611 | |

| PE1 | 0.815 | |||

| PE2 | 0.806 | |||

| PE3 | 0.802 | |||

| PE4 | 0.795 | |||

| PE5 | 0.793 | |||

| PE6 | 0.789 | |||

| PE7 | 0.789 | |||

| PE8 | 0.788 | |||

| PE9 | 0.784 | |||

| PE10 | 0.781 | |||

| PE11 | 0.779 | |||

| PE12 | 0.774 | |||

| PE13 | 0.767 | |||

| PE14 | 0.672 | |||

| Parental Autonomous Support (T1) | 0.941 | 0.946 | 0.597 | |

| PA1 | 0.785 | |||

| PA2 | 0.783 | |||

| PA3 | 0.781 | |||

| PA4 | 0.778 | |||

| PA5 | 0.777 | |||

| PA6 | 0.777 | |||

| PA7 | 0.773 | |||

| PA8 | 0.771 | |||

| PA9 | 0.766 | |||

| PA10 | 0.764 | |||

| PA11 | 0.763 | |||

| PA12 | 0.758 | |||

| Self-Assessment (T1/T2) | 0.926 (0.923) | 0.922 (0.921) | 0.597 (0.594) | |

| SE1 | 0.795(0.798) | |||

| SE2 | 0.787(0.789) | |||

| SE3 | 0.779(0.777) | |||

| SE4 | 0.775(0.776) | |||

| SE5 | 0.767(0.772) | |||

| SE6 | 0.766(0.756) | |||

| SE7 | 0.758(0.750) | |||

| SE8 | 0.756(0.749) | |||

| Self-Acceptance (T1/T2) | 0.911 (0.910) | 0.909 (0.910) | 0.558 (0.560) | |

| SA1 | 0.797(0.784) | |||

| SA2 | 0.793(0.781) | |||

| SA3 | 0.781(0.763) | |||

| SA4 | 0.762(0.751) | |||

| SA5 | 0.758(0.747) | |||

| SA6 | 0.742(0.743) | |||

| SA7 | 0.683(0.740) | |||

| SA8 | 0.651(0.675) | |||

| Academic Ability Self-Efficacy (T1/T2) | 0.947 (0.948) | 0.930 (0.931) | 0.548 (0.551) | |

| AC1 | 0.768(0.762) | |||

| AC2 | 0.766(0.761) | |||

| AC3 | 0.762(0.754) | |||

| AC4 | 0.759(0.753) | |||

| AC5 | 0.742(0.753) | |||

| AC6 | 0.740(0.750) | |||

| AC7 | 0.738(0.734) | |||

| AC8 | 0.738(0.731) | |||

| AC9 | 0.713(0.728) | |||

| AC10 | 0.712(0.724) | |||

| AC11 | 0.708(0.714) | |||

| Academic Behavior Self-Efficacy (T1/T2) | 0.941 (0.934) | 0.922 (0.914) | 0.518 (0.495) | |

| AB1 | 0.761(0.730) | |||

| AB2 | 0.754(0.719) | |||

| AB3 | 0.751(0.716) | |||

| AB4 | 0.733(0.711) | |||

| AB5 | 0.723(0.710) | |||

| AB6 | 0.720(0.703) | |||

| AB7 | 0.703(0.701) | |||

| AB8 | 0.700(0.700) | |||

| AB9 | 0.694(0.694) | |||

| AB10 | 0.694(0.679) | |||

| AB11 | 0.685(0.670) | |||

| Intrinsic Emotional Engagement in PE (T2) | 0.944 | 0.925 | 0.554 | |

| IE1 | 0.766 | |||

| IE2 | 0.759 | |||

| IE3 | 0.757 | |||

| IE4 | 0.756 | |||

| IE5 | 0.751 | |||

| IE6 | 0.750 | |||

| IE7 | 0.748 | |||

| IE8 | 0.741 | |||

| IE9 | 0.712 | |||

| IE10 | 0.702 | |||

| Extrinsic Emotional Engagement in PE (T2) | 0.946 | 0.925 | 0.508 | |

| EL1 | 0.782 | |||

| EL2 | 0.743 | |||

| EL3 | 0.734 | |||

| EL4 | 0.727 | |||

| EL5 | 0.716 | |||

| EL6 | 0.714 | |||

| EL7 | 0.709 | |||

| EL8 | 0.707 | |||

| EL9 | 0.702 | |||

| EL10 | 0.697 | |||

| EL11 | 0.664 | |||

| EL12 | 0.652 |

| Variable | χ2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE Teacher Support | |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 378.357 | 335 | 0.995 | 0.995 | 0.013 | - | - |

| Weak Invariance | 426.208 | 348 | 0.991 | 0.991 | 0.018 | −0.004 | 0.005 |

| Strong Invariance | 2388.130 | 376 | 0.778 | 0.777 | 0.086 | −0.217 | 0.073 |

| Parental Autonomy Support | |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 225.807 | 239 | 1.000 | 1.002 | 0.000 | - | - |

| Weak Invariance | 246.182 | 250 | 1.000 | 1.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Strong Invariance | 814.793 | 274 | 0.934 | 0.933 | 0.052 | −0.066 | 0.052 |

| Self-acceptance | |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 562.923 | 442 | 0.989 | 0.988 | 0.020 | - | - |

| Weak Invariance | 588.334 | 456 | 0.988 | 0.987 | 0.020 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Strong Invariance | 3874.799 | 488 | 0.703 | 0.698 | 0.098 | −0.029 | 0.078 |

| Academic Self-efficacy | |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 1258.557 | 874 | 0.978 | 0.976 | 0.025 | - | - |

| Weak Invariance | 1296.023 | 894 | 0.977 | 0.975 | 0.025 | −0.001 | 0.000 |

| Strong Invariance | 3637.430 | 937 | 0.843 | 0.842 | 0.063 | −0.135 | 0.038 |

| PE Learning Emotional Engagement | |||||||

| Configural Invariance | 2524.444 | 965 | 0.921 | 0.915 | 0.047 | - | - |

| Weak Invariance | 2589.883 | 987 | 0.919 | 0.915 | 0.048 | −0.002 | 0.001 |

| Strong Invariance | 4883.011 | 1033 | 0.805 | 0.804 | 0.072 | −0.116 | 0.025 |

| Time Point | Standardized Loading | Standard Error | CR | Hypothesis Test Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Self-acceptance and Academic Self-efficacy | ||||

| PE Teacher Support T1→Self-acceptance T1 | 0.354 | 0.011 | 8.915 | Supported |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Self-acceptance T1 | 0.402 | 0.018 | 10.042 | Supported |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T1 | 0.137 | 0.018 | 3.996 | Supported |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T1 | 0.181 | 0.031 | 12.757 | Supported |

| Self-acceptance T1→Academic Self-efficacy T1 | 0.704 | 0.103 | 12.757 | Supported |

| PE Teacher Support T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.082 | 0.014 | 3.431 | Supported |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.076 | 0.024 | 3.017 | Supported |

| Self-acceptance T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.340 | 0.146 | 4.807 | Supported |

| T2 Self-acceptance and Academic Self-efficacy | ||||

| PE Teacher Support T1→Self-acceptance T2 | 0.358 | 0.010 | 8.862 | Supported |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Self-acceptance T2 | 0.415 | 0.017 | 10.114 | Supported |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T2 | 0.154 | 0.018 | 4.357 | Supported |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T2 | 0.148 | 0.031 | 4.010 | Supported |

| Self-acceptance T2→Academic Self-efficacy T2 | 0.710 | 0.117 | 12.071 | Supported |

| PE Teacher Support T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.066 | 0.014 | 2.738 | Supported |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.085 | 0.024 | 3.399 | Supported |

| Self-acceptance T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.276 | 0.158 | 3.926 | Supported |

| Academic Self-efficacy T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.618 | 0.082 | 8.513 | Supported |

| Path | Effect Value | Standard Error | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediation Model T1 | |||||

| Total Effect | 0.242 | 0.018 | 0.206 | 0.277 | 100% |

| Direct Effect | 0.047 | 0.014 | 0.019 | 0.075 | 19.42% |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Self-acceptance T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.070 | 0.017 | 0.040 | 0.106 | 28.92% |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.044 | 0.014 | 0.020 | 0.073 | 18.18% |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Self-acceptance T1→Academic Self-efficacy T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.080 | 0.014 | 0.057 | 0.113 | 33.05% |

| Total Effect | 0.448 | 0.060 | 0.371 | 0.608 | 100% |

| Direct Effect | 0.073 | 0.025 | 0.022 | 0.122 | 15.14% |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Self-acceptance T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.130 | 0.031 | 0.076 | 0.198 | 26.97% |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.096 | 0.024 | 0.053 | 0.148 | 19.91% |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Self-acceptance T1→Academic Self-efficacy T1→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.150 | 0.025 | 0.107 | 0.207 | 31.12% |

| Mediation Model T2 | |||||

| Total Effect | 0.242 | 0.018 | 0.206 | 0.277 | 100% |

| Direct Effect | 0.039 | 0.014 | 0.011 | 0.067 | 16.11% |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Self-acceptance T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.057 | 0.018 | 0.028 | 0.098 | 23.55% |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.055 | 0.016 | 0.026 | 0.089 | 22.72% |

| PE Teacher Support T1→Self-acceptance T2→Academic Self-efficacy T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.091 | 0.016 | 0.065 | 0.127 | 37.60% |

| Total Effect | 0.450 | 0.029 | 0.395 | 0.508 | 100% |

| Direct Effect | 0.081 | 0.024 | 0.031 | 0.128 | 18% |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Self-acceptance T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.109 | 0.032 | 0.053 | 0.179 | 24.22% |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Academic Self-efficacy T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.087 | 0.027 | 0.038 | 0.146 | 19.33% |

| Parental Autonomy Support T1→Self-acceptance T2→Academic Self-efficacy T2→PE Learning Emotional Engagement T2 | 0.173 | 0.027 | 0.128 | 0.236 | 38.44% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, Q.; Xuan, S.; Zhang, T.; Zong, B. How Autonomy Support Sustains Emotional Engagement in College Physical Education: A Longitudinal Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060822

Xia Q, Xuan S, Zhang T, Zong B. How Autonomy Support Sustains Emotional Engagement in College Physical Education: A Longitudinal Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060822

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Qifei, Shu Xuan, Tingxiao Zhang, and Bobo Zong. 2025. "How Autonomy Support Sustains Emotional Engagement in College Physical Education: A Longitudinal Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060822

APA StyleXia, Q., Xuan, S., Zhang, T., & Zong, B. (2025). How Autonomy Support Sustains Emotional Engagement in College Physical Education: A Longitudinal Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 822. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060822