Leveraging an Arts-Based Approach to Foster Engagement, Nurture Kindness, and Prevent Violence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Advantages of Implementing an Arts-Based Approach

2.2. Using an Arts-Based Approach to Nurture Kindness

2.3. Applying an Arts-Based Approach to Foster Civic Learning

2.4. Harnessing the Power of the Arts to Encourage Community Egagement

3. Model Framework

4. Method

4.1. Project Description

4.2. Data Collection

4.3. Data Analysis

5. Findings

5.1. The Inherent Benefits of the Arts

I think what they get out of it is a little bit of self-love. I feel like they … feel a little more content, … a little bit more joyous and comfortable within themselves … the comfortability of coming together and building something and being able to share an experience or being able to share laughter.(P3)

Arts engagement also served a therapeutic purpose (Beerse et al., 2020), where participating in artistic activities contributed to enhanced mindfulness, allowing the participants to focus on the positive aspects of life rather than dwelling on the negative, as depicted in the following quotes:Sometimes, if they’re feeling … depressed or sad, … you (painting wooden crafts that convey positive messages) bring some hope or some sunshine.(P11)

Working on painting is therapeutic for them and also the classes … creating peace and recognizing what is violence [sic].(P2)

Most of them (homeless shelter residents) … they express their emotions in different ways. … Having these … activities … it takes out all stress … try not to think about anything other than what they are doing and just focus on this (the present).(P6)

You’re creating … awareness through art. … It’s kinesthetic. … You are touching. You are feeling. And you are using your senses. … It’s a full implementation of other senses.(P7)

They had the opportunity to show that creativity while sending out a positive message. … That art activity … was amazing for them.(P4)

I think [it] really resonated with the kiddos [sic]. … They had so much fun and they were excited about being in the gallery and all that. So, it was really nice.(P5)

Drawing and painting gave participants a unique and creative way to express their diverse perspectives on kindness within their community. This was exemplified by one of the school staff members, who highlighted the students’ various ways of interpreting, sharing, and spreading kindness through the arts.They want to have that feeling of, “Uh, I’m able to give something to someone.” “Someone’s going to be able to see what I did.” And they take pride in it.(P14)

In resource-limited communities, the arts could serve as a valuable means of enrichment by providing opportunities for personal growth and cultural engagement that might otherwise be inaccessible, as highlighted by a shelter staff member:It was insightful to see what’s in their little brains, like how they identify kindness. … Some of them identify it through friendship. Some of them through family, through animals, through the world, so … you can kind of get an inside [sic] on how their little brains are working and what they think is valuable.(P5)

The children … the only involvement they ever get is the ones that are in school. So when they come and they do projects, activities, events here in the shelter, it’s very rewarding for them. And it gets them to be themselves. … They’re enjoying themselves for who they are.(P10)

They were also doing it (art activities) with their moms, … so I think that was a really good bonding experience for everybody.(P9)

I’ve seen … some of the women that [sic] don’t necessarily come out; a lot of them have already come out and started … talking more, interacting more with the women, so it does help.(P12)

I can talk about the cake decorating. … All the ladies were able to decorate … cupcakes and kind of talked to each other … co-existed, talked about how they feel, and … how things are going … and kind of … bring [sic] together the women. And it was really nice.(P3)

5.2. Promoting Kindness and Preventing Violence Through Artistic Expression

Continuing to have more activities, maybe guest speakers. … When it’s someone else talking to the kids, that will motivate the kids and engage them. They listen cause [sic] it’s someone outside of the school.(P4)

If kids hear it in some different ways, … it fosters that kindness in the school. They’re not just hearing it from us, they’re hearing it from others, … agencies outside our school. So, it makes sense to them that kindness is something that … should be implemented not only at school but at home, everywhere else.(P7)

Teaching children to respect one another from the beginning and … staying away from hatred. … Children are like sponges and they absorb everything … and they internalize that. So, teaching them “No! … respect is better, working together is better.”(P8)

Making kids aware of what’s wrong, what’s … right. … And … one of our core values is accountability, students need to be made aware that … they must be accountable for their actions and violence should never be … the resort. So, making kids aware of different choices.(P7)

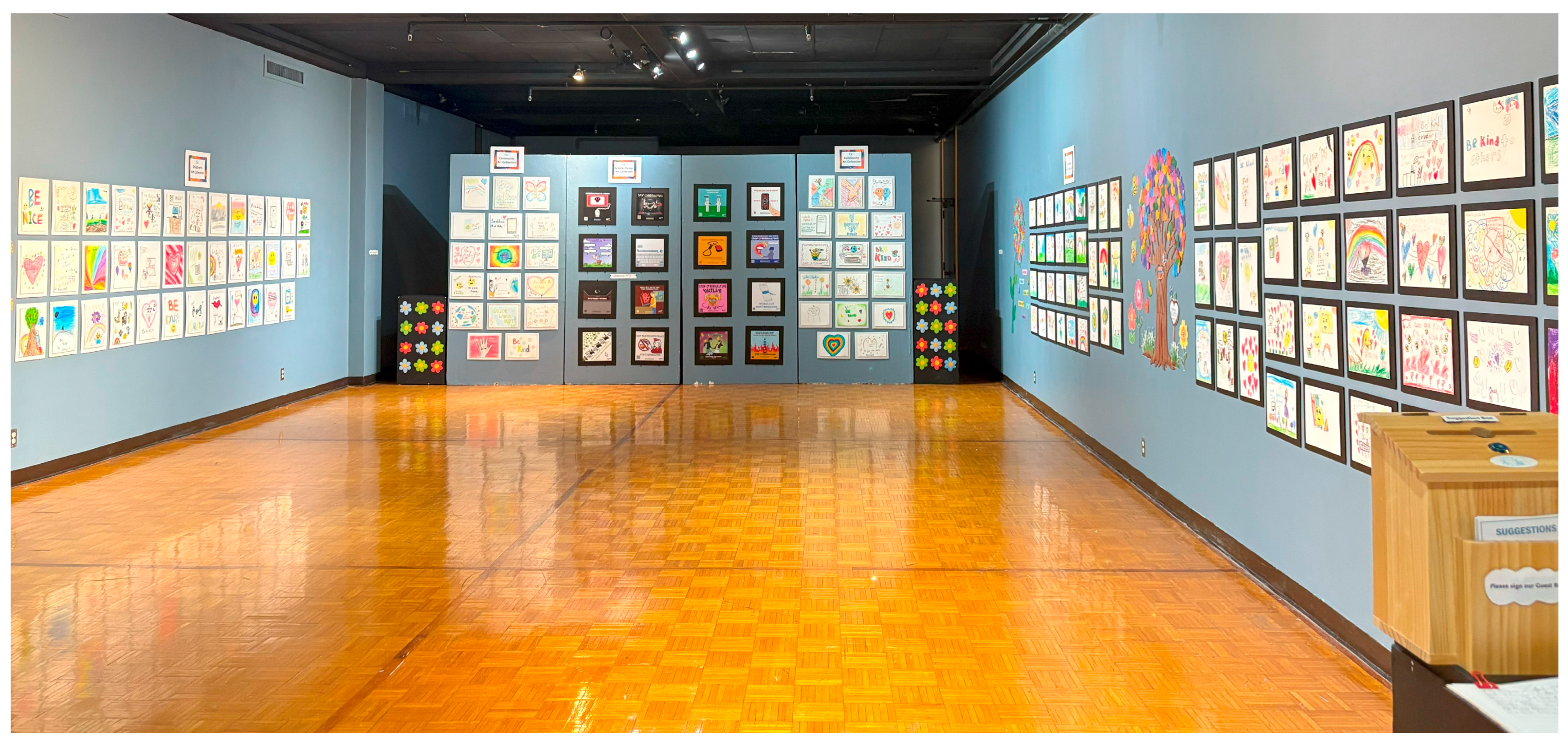

Additionally, hosting community events provided a valuable opportunity to raise awareness, engage the community, increase exposure to important issues, and create a sense of collective responsibility to promote social change. Our two art exhibitions (Figure 1 and Figure 2) attracted hundreds of visitors over the course of two weeks and one week, respectively. One of the community partners shared her perspective:Sometimes kids do things and … they’re not fully aware of what it is. Like bullying, for example. So, they might think, “Oh, that? We’re just teasing each other,” but it could be seen as bullying. So, I think … educating them so that they know exactly what it is, and then providing tools and resources so that it doesn’t happen.(P15)

Having … events that promote kindness and … spread love, and kind of … set some sort of motion within the community. … I think events that … give out positivity … would be really cool.(P3)

5.3. Teaching Civic Responsibility Through the Arts

I think our kiddos [sic], from what I’ve seen, tend to live in a very narrow world. … I think getting them more involved in the community and out of their phones and technology … would be very helpful.(P5)

Maybe … an act of kindness … where … they’re put to … make something. Maybe a craft, maybe a little gift, … and they go out and share it with the community. … I think that’s one of the ways … you can show civic kindness.(P3)

We’re trying to create an environment of intrinsic motivation. … You should always behave a certain way not just because you’re gonna [sic] receive a reward but because it’s the right thing to do. … This is our main focus in the school.(P7)

5.4. Practical Strategies for Collaborating with Community Partners

The community partners also appreciated the project’s flexibility, as the project team was willing to accommodate their schedules and the needs of the organizations and schools and made themselves readily available. Punctuality was key to ensuring things were well planned and speakers were on time. Sending gentle reminders and reliably following up also helped ensure that tasks stayed on track and deadlines were met. Additionally, consistency was another key factor our community partners found critical:I know that you guys … were very deliberate … with what kind of lessons you brought in, the materials, the resources you provided. Everything was very well organized. I think that REACH did an awesome job at keeping track of the numbers coming in and … setting up and the way … we were able to reach every single student I think was awesome!(P1)

Other key qualities include patience, a mission-driven mindset, responsiveness, organization, and attention to detail. One of the community partners shared her perception:Consistency is very important to them (shelter residents). … Even though you have one person here, you are here, so … they know that they can count on you. … And I believe that has a lot to do with … being … truthful to what you do.(P11)

The treatment of the community partners is equally important. Having team members who were approachable, supportive, and genuinely interested fostered positive relationships, as illustrated by one of the quotes:You all as a…[team] are very organized and detailed, and … very efficient. And … you can tell you love what you do. So … it has been motivating but also really nice to work with you all.(P5)

[Project team member] … does her homework. She follows up. She asks a lot of really great questions because she is coming in from the outside, so she’s very prepared. She is always asking questions about what can be done, what can’t be done, … what my thoughts are. … So, it has been a good experience.(P14)

I did … like the fact that REACH … focuses a lot on the character values. … We are actually … a national character school. So … the fact that … the agency outside of school was able to help us bring some … workshops for the kids, it worked very well. … It was … good integration of resources.(P7)

For me as a school counselor, I promote … the empathy portion. I promote for kids … to be kind to one another … using their words. … It (the activity) just goes hand in hand with what I’m doing, our mission … to provide that safety net for our students. … And I think it just matched our goals.(P1)

As with any community-based project, collaborations and partnerships inevitably face challenges. We also asked our community partners to discuss the challenges that they have encountered throughout our collaboration. Scheduling conflicts tended to be one of the most commonly raised challenges, as illustrated below:So everything that you guys … are doing and teaching kind of falls in line with our school’s mission and vision. … Your kindness, lessons, and activities fit right in to what we’re already trying to teach them here.(P15)

I’d say … arranging the time, and … that’s not necessarily on your end but more on the campus end. … Finding the time … the dates, the time the classes that we were working with … so it doesn’t impede too much with instruction, but that’s more on the campus end.(P4)

Sometimes, even if community partners believed that the activities our project brings benefit the community they serve, they still needed to convince their client population and secure buy-in from the administration, as revealed by one of the shelter staff members:As a school, I know … our schedules are crazy and there are last-minute changes, and even with that, you guys have been very patient. And you’ve been able to work with us … because things just come up or administration will make changes at the last minute. So, I’m grateful for that as well.(P5)

It’s hard for the mothers and the children to envision the benefits of things that they never experience. … Trying to convince them, trying to show them this is great—it’s not a chore, it’s not boring. … It’s something that is gonna [sic] help you. That, you know, is kind of tricky but you guys have been able to do that.(P8)

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. The Power of Creative Expression

6.2. Strengthening Accessibility and Inclusion

6.3. Supporting Sustainability and Longevity

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allen, C., Frankel, E., Watanabe-Galloway, S., Keeler, H., Palm, D., Fitzpatrick, B., Estabrooks, P., & King, K. M. (2024). Driving key partner engagement by integrating community-engaged principles into a stakeholder analysis: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science, 8(1), e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, S., Leach, B., Bousfield, J., Smith, P., & Marjanovic, S. (2021). Arts-based approaches to public engagement with research: Lessons from a rapid review. RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RRA100/RRA194-1/RAND_RRA194-1.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Beerse, M. E., Van Lith, T., & Stanwood, G. (2020). Therapeutic psychological and biological responses to mindfulness-based art therapy. Stress and Health, 36(4), 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdychevsky, L., Stodolska, M., & Shinew, K. J. (2019). The roles of recreation in the prevention, intervention, and rehabilitation programs addressing youth gang involvement and violence. Leisure Sciences, 44(3), 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhui, K. S., Hicks, M. H., Lashley, M., & Jones, E. (2012). A public health approach to understanding and preventing violent radicalization. BMC Medicine, 10(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, N. A., Ramos, S., Dorsainvil, M., Wooten, C., Ridenour, T. A., Yaros, A., Johnson-Lawrence, V., Fields-Johnson, D., Khalid, N., & Graham, P. (2023). Resilience-informed community violence prevention and community organizing strategies for implementation: Protocol for a hybrid type 1 implementation-effectiveness trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 12, e50444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blevins, B., LeCompte, K. N., Riggers-Piehl, T., Scholten, N., & Magill, K. R. (2020). The impact of an action civics program on the community & political engagement of youth. The Social Studies, 112(3), 146–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bone, J. K., Bu, F., Fluharty, M. E., Paul, E., Sonke, J. K., & Fancourt, D. (2022). Arts and cultural engagement, reportedly antisocial or criminalized behaviors, and potential mediators in two longitudinal cohorts of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 51(8), 1463–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyes, L. C., & Reid, I. (2005). What are the benefits for pupils participating in arts activities? Research in Education, 73(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branje, S., de Moor, E. L., Spitzer, J., & Becht, A. I. (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 908–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braunwalder, C., Müller, R., Glisic, M., & Fekete, C. (2022). Are positive psychology interventions efficacious in chronic pain treatment? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Medicine, 23(1), 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships. (2024). The Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships’ approach to targeted violence and terrorism prevention. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2024-11/2024_1112_cp3_approach-to-prevention.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Chan, M. W. M., Lo, S. H. S., Sit, J. W. H., Choi, K. C., & Tao, A. (2023). Effects of visual arts-based interventions on physical and psychosocial outcomes of people with stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 5, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaraman, L., & Hall, G. (2011). School dropout prevention: What arts-based community and out-of-school-time programs can contribute. New Directions for Youth Development, 2011(Suppl. S1), 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, B., Jones, L., Jones, A., Corbett, C. E., Booker, T., Wells, K. B., & Collins, B. (2009). Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. American Journal of Public Health, 99(2), 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coholic, D. A. (2011). Exploring the feasibility and benefits of arts-based mindfulness-based practices with young people in need: Aiming to improve aspects of self-awareness and resilience. Child & Youth Care Forum, 40(4), 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawadi, S. (2020). Thematic analysis approach: A step by step guide for ELT research practitioners. Journal of Nelta, 25(1–2), 62–71. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED612353.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs. (2024). Community violence intervention: A collaborative approach to addressing community violence. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/archive/topics/community-violence-intervention (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Edwards, B. M., Smart, E., King, G., Curran, C. J., & Kingsnorth, S. (2018). Performance and visual arts-based programs for children with disabilities: A scoping review focusing on psychosocial outcomes. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(4), 574–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezell, M., & Levy, M. (2003). An evaluation of an arts program for incarcerated juvenile offenders. Journal of Correctional Education, 54(3), 108–114. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41971150 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Fancourt, D., & Ali, H. (2019). Differential use of emotion regulation strategies when engaging in artistic creative activities amongst those with and without depression. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fancourt, D., & Finn, S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review (Health Evidence Network synthesis report No. 67). WHO Regional Office for Europe. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553778/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Fancourt, D., Garnett, C., & Müllensiefen, D. (2020). The relationship between demographics, behavioral and experiential engagement factors, and the use of artistic creative activities to regulate emotions. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2021). Strategic intelligence assessment and data on domestic terrorism. Available online: https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/21_0514_strategic-intelligence-assessment-data-domestic-terrorism_0.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2024). FBI releases 2023 active shooter incidents in the United States Report. Available online: https://www.fbi.gov/news/press-releases/fbi-releases-2023-active-shooter-incidents-in-the-united-states-report (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Forrest-Bank, S., Nicotera, N., Bassett, D. M., & Ferrarone, P. (2016). Effects of an expressive art intervention with urban youth in low-income neighborhoods. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 33(5), 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryburg, D. A. (2022). Kindness as a stress reduction–health promotion intervention: A review of the psychobiology of caring. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 16(1), 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goicoechea, J., Wagner, K., Yahalom, J., & Medina, T. (2014). Group counseling for at-risk African American youth: A collaboration between therapists and artists. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 9(1), 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, A., González-Ortiz, L. G., Gabutti, L., & Lumera, D. (2025). What’s the role of kindness in the healthcare context? A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 25(1), 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y. (2024). Potentials of arts education initiatives for promoting emotional wellbeing of Chinese university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1349370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardiman, M. M. (2019). The arts, creativity, and learning: From research to practice. In J. Contreras-Vidal, D. Robleto, J. Cruz-Garza, J. Azorín, & C. Nam (Eds.), Mobile brain-body imaging and the neuroscience of art, innovation and creativity (Vol. 10). Springer Series on Bio-and Neurosystems. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hass-Cohen, N., Bokoch, R., Clyde Findlay, J., & Banford Witting, A. (2018). A four-drawing art therapy trauma and resiliency protocol study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 61, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, R. T. H., Chan, C. K. P., Fong, T. C. T., Lee, P. H. T., Lum, D. S. Y., & Suen, S. H. (2020). Effects of expressive arts–based interventions on adults with intellectual disabilities: A stratified randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, H. (2013). Mitigating barriers to civic engagement for low-income, minority youth ages 13–18: Best practices from Environmental Youth Conferences. Journal of Youth Development, 8(3), 130803PA002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S. G., Grossman, P., & Hinton, D. E. (2011). Loving-kindness and compassion meditation: Potential for psychological interventions. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1126–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Berluche, D. (2024). Creative expression and mental health. Journal of Creativity, 34(2), 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A., & Bonde, L. O. (2018). The use of arts interventions for mental health and well-being in health settings. Perspect Public Health, 138(4), 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S., Goncalo, J. A., & Rodas, M. A. (2023). The cost of freedom: Creative ideation boosts both feelings of autonomy and the fear of judgment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 105, 104432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucerova, B., Levit-Binnun, N., Gordon, I., & Golland, Y. (2023). From Oxytocin to compassion: The saliency of distress. Biology, 12(2), 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansing, A. E., Romero, N. J., Siantz, E., Silva, V., Center, K., Casteel, D., & Gilmer, T. (2023). Building trust: Leadership reflections on community empowerment and engagement in a large urban initiative. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L., Currie, V., Saied, N., & Wright, L. (2020). Journey to hope, self-expression and community engagement: Youth-led arts-based participatory action research. Children and Youth Services Review, 109, 104581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, L., Robertson, P., & Lindsey, B. (2018). Expressive arts and mindfulness: Aiding adolescents in understanding and managing their stress. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 13(3), 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 9(3). Available online: http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Malin, H. (2015). Arts participation as a context for youth purpose. Studies in Art Education, 56(3), 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, M., Rollero, C., Rizzo, M., Di Carlo, S., De Piccoli, N., & Fedi, A. (2023). Educating youth to civic engagement for social justice: Evaluation of a secondary school project. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, N. (2016). Compassion and the science of kindness: Harvard Davis Lecture 2015. The British Journal of General Practice, 66(648), e525–e527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreland, A. (2024). The sudden and lasting impact of hate-based mass violence. The Community Policing Dispatch, 17(2). U.S. Department of Justice, Community Oriented Policing Services. Available online: https://cops.usdoj.gov/html/dispatch/02-2024/mass_violence_impact.html (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Morison, L., Simonds, L., & Stewart, S. J. F. (2021). Effectiveness of creative arts-based interventions for treating children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events: A systematic review of the quantitative evidence and meta-analysis. Arts & Health, 14(3), 237–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morizio, L. J., Cook, A. L., Troeger, R., & Whitehouse, A. (2022). Creating compassion: Using art for empathy learning with urban youth. Contemporary School Psychology, 26(4), 435–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, R., Gertz, K. J., Molton, I. R., Terrill, A. L., Bombardier, C. H., Ehde, D. M., & Jensen, M. P. (2016). Effects of a tailored positive psychology intervention on well-being and pain in individuals with chronic pain and a physical disability: A feasibility trial. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 32(1), 32–44. Available online: https://journals.lww.com/clinicalpain/fulltext/2016/01000/effects_of_a_tailored_positive_psychology.5.aspx (accessed on 1 May 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naeem, M., Ozuem, W., Howell, K., & Ranfagni, S. (2023). A step-by-step process of thematic analysis to develop a conceptual model in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 16094069231205789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). Promoting positive adolescent health behaviors and outcomes: Thriving in the 21st century (3rd ed.). National Academies Press. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554988/ (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. (2021). Arts-based programs and arts therapies for at-risk, justice-involved, and traumatized youths. Available online: https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/model-programs-guide/literature-reviews/arts-based-programs-and-arts-therapies-risk-justice-involved-and-traumatized#0-0 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Oren, R., Orkibi, H., Elefant, C., & Salomon-Gimmon, M. (2019). Arts-based psychiatric rehabilitation programs in the community: Perceptions of healthcare professionals. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(1), 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Y.-F., & Lin, M. (2024). A socio-ecological approach to understanding the utility of kindness in promoting wellness: A conceptual paper. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 10, 101159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Y.-F., Torres-Hostos, L., Garcia Tovar, D., Camacho, E., Zamora, H., & Myers, N. W. (2023). An integrated ecological approach to countering targeted violence on the US-Mexico Border: Insights and lessons learned. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 51(4), 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, R., Mason-Bertrand, A., Tymoszuk, U., Spiro, N., Gee, K., & Williamon, A. (2021). Arts engagement supports social connectedness in adulthood: Findings from the HEartS survey. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, J., Mettler, J., Cho, S., & Heath, N. L. (2024). The effects of loving-kindness interventions on positive and negative mental health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 110, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, S., & Webster, N. (2021). A conceptual model of intergroup contact, social capital, and youth civic engagement for diverse democracy. Local Development & Society, 4(2), 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REACH Violence Prevention. (2024). REACH’s Peace & Kindness Art Exhibition 2024. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QyZrBt2acdM (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- REACH Violence Prevention. (2025). REACH’s Peace & Kindness II Art Exhibition 2025. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EJ8ih_JmFZo (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Red & Blue Works. (2019). From civic education to a civic learning ecosystem: A landscape analysis and case for collaboration. Available online: https://citizensandscholars.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Civic-Learning-White-Paper.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Sagiv, I. B., Goldner, L., & Carmel, Y. (2022). The civic engagement community participation thriving model: A multi-faceted thriving model to promote socially excluded young adult women. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 955777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, D. (2009). Leadership, education, achievement, and development: A nursing intervention for prevention of youthful offending behavior. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 14(6), 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, A., Choudhari, S. G., Gaidhane, A. M., & Quazi Syed, Z. (2022). Role of art therapy in the promotion of mental health: A critical review. Cureus, 14(8), e28026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, K. M., Levy, S. J., & Bukstein, O. G. (2022). Adolescent substance use disorders. NEJM Evidence, 1(6), EVIDra2200051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soni, A., & Tekin, E. (2023). How do mass shootings affect community well-being? The Journal of Human Resources, 60(3), 1220-11385R1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UCLA Library. (n.d.). Critical media literacy: Engaging media and transforming education. Available online: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/educ466 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Vaartio-Rajalin, H., Santamäki-Fischer, R., Jokisalo, P., & Fagerström, L. (2021). Art making and expressive art therapy in adult health and nursing care: A scoping review. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 8(1), 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lith, T., Schofield, M. J., & Fenner, P. (2012). Identifying the evidence-base for art-based practices and their potential benefit for mental health recovery: A critical review. Disability and Rehabilitation, 35(16), 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J. (2023). Kindness in British communities: Discursive practices of promoting kindness during the COVID pandemic. Discourse & Society, 34(4), 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Paat, Y.-F.; Garcia Tovar, D.; Myers, N.W.; Orezzoli, M.C.E.; Giangiulio, A.M.; Ruiz, S.L.; Dorado, A.V.; Torres-Hostos, L.R. Leveraging an Arts-Based Approach to Foster Engagement, Nurture Kindness, and Prevent Violence. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060799

Paat Y-F, Garcia Tovar D, Myers NW, Orezzoli MCE, Giangiulio AM, Ruiz SL, Dorado AV, Torres-Hostos LR. Leveraging an Arts-Based Approach to Foster Engagement, Nurture Kindness, and Prevent Violence. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):799. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060799

Chicago/Turabian StylePaat, Yok-Fong, Diego Garcia Tovar, Nathan W. Myers, Max C. E. Orezzoli, Anne M. Giangiulio, Sarah L. Ruiz, Angela V. Dorado, and Luis R. Torres-Hostos. 2025. "Leveraging an Arts-Based Approach to Foster Engagement, Nurture Kindness, and Prevent Violence" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060799

APA StylePaat, Y.-F., Garcia Tovar, D., Myers, N. W., Orezzoli, M. C. E., Giangiulio, A. M., Ruiz, S. L., Dorado, A. V., & Torres-Hostos, L. R. (2025). Leveraging an Arts-Based Approach to Foster Engagement, Nurture Kindness, and Prevent Violence. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 799. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060799