Multicultural Interactions Decrease the Tendency to View Any Act as Unambiguously Wrong: The Moderating Role of Moral Flexibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Multicultural Experiences Influence Moral Judgments

1.2. Different Types of MCEs

1.3. The Moderating Effect of Moral Flexibility

1.4. Overview of Studies

2. Study 1: Studying Abroad Decreases the Tendency to View Acts as Unambiguously Wrong

2.1. Methods

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Materials

2.1.3. Procedure

2.2. Results and Discussion

3. Study 2 Correlational Evidence of MI (Not ME) Affecting Moral Judgments

3.1. Methods

3.1.1. Participants

3.1.2. Materials

3.1.3. Procedure

3.2. Results and Discussion

3.2.1. Multi-Dimension of MCEs

3.2.2. MCEs and Moral Judgment

4. Study 3: Experimental Evidence of MI (Not ME) Affecting Moral Judgments

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Participants

4.1.2. Materials

4.1.3. Procedure

4.2. Results and Discussion

4.2.1. MCEs Manipulation Check

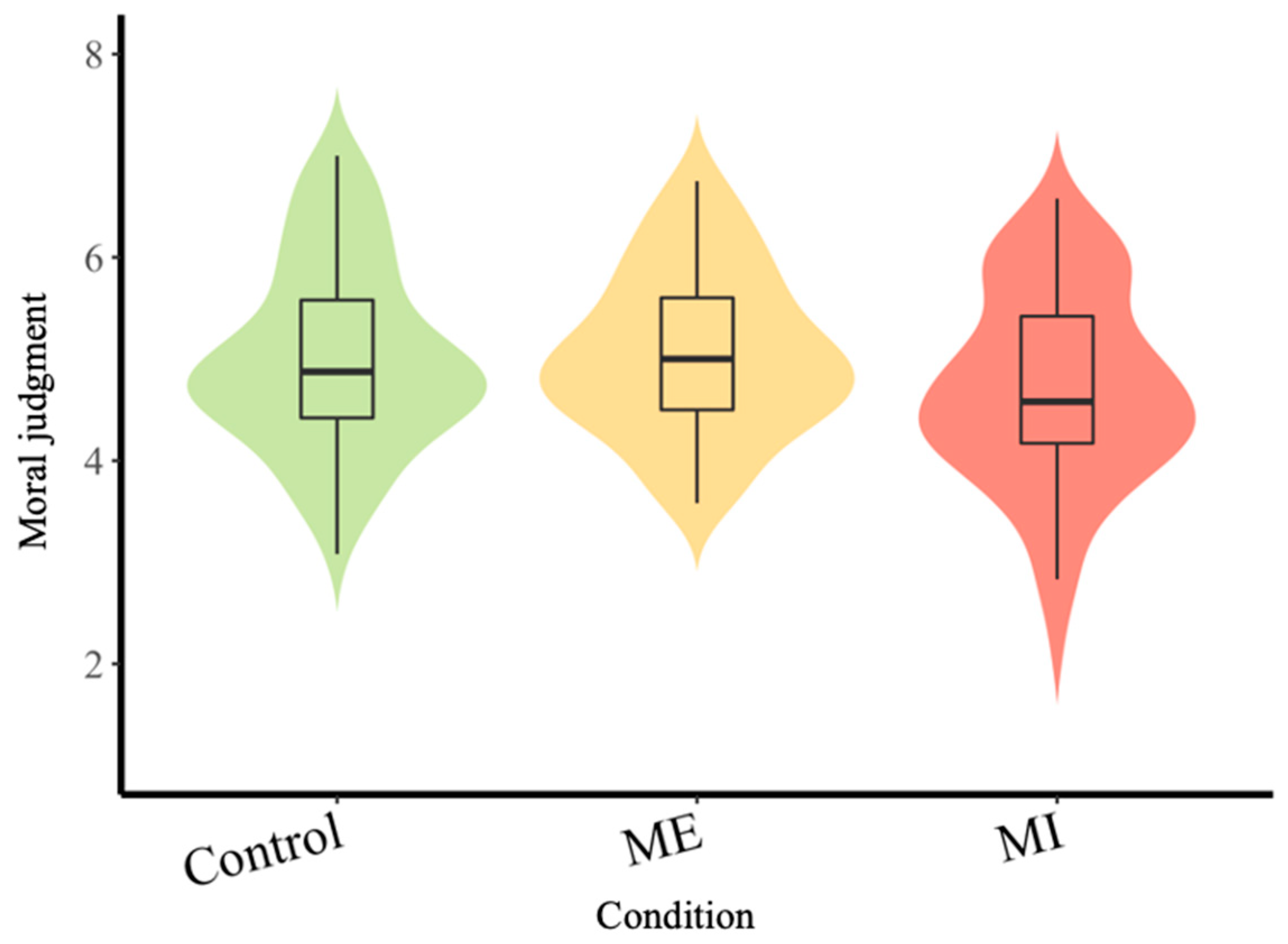

4.2.2. The Effects of ME and MI on Moral Judgments

5. Study 4: Moral Flexibility Moderates the Effect of MI on Moral Judgments

5.1. Methods

5.1.1. Participants

5.1.2. Materials

5.1.3. Procedure

5.2. Results and Discussion

5.2.1. MCE Manipulation Check

5.2.2. The Effects of MI on Moral Judgments

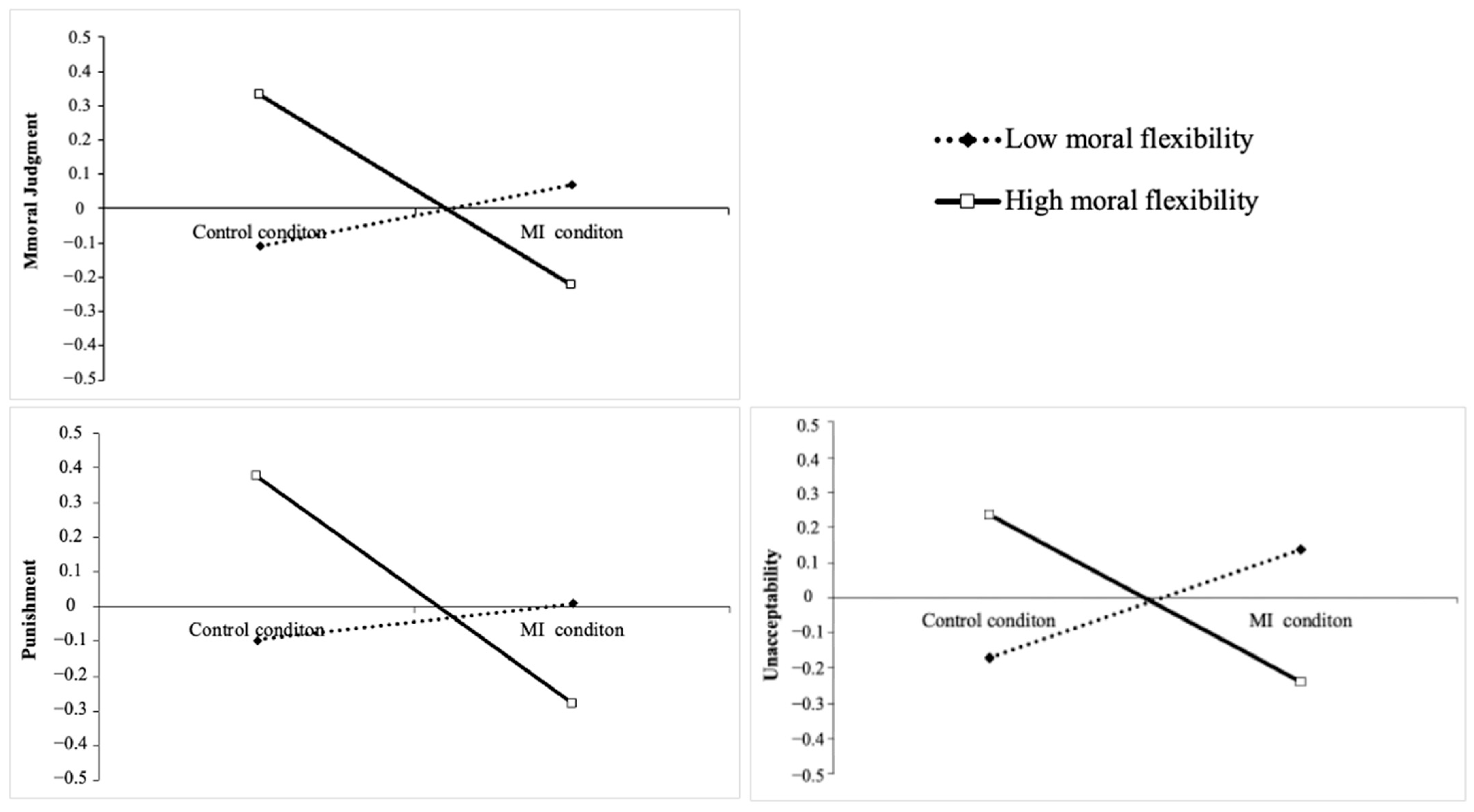

5.2.3. The Moderating Effect of Moral Flexibility

6. Meta-Analytic Overview

7. General Discussion

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Study 1 and 2 Scenarios

- Lie on your taxes

- Make a fraudulent resume

- Take public transportation without buying a ticket

- Accept bribes

- Cheat on a romantic partner

- Cheat on a test

- Insult an overweight classmate/colleague

- Blame a coworker for your mistake

- Appropriate shared bicycles for your own use

- Kick a dog

- Violence against others

- Keep extra change a sales clerk accidentally gives you

- Study 3 and 4 Scenarios

- Scenario 1

- Scenario 2

- Scenario 3

- Scenario 4

References

- Adam, H., Obodaru, O., Lu, J. G., Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2018). The shortest path to oneself leads around the world: Living abroad increases self-concept clarity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 145, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Affinito, S. J., Antoine, G. E., Gray, K., & Maddux, W. W. (2023). Negative multicultural experiences can increase intergroup bias. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 109, 104498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. Holt, Rinehart, & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Andrejević, M., Smillie, L. D., Feuerriegel, D., Turner, W. F., Laham, S. M., & Bode, S. (2021). How do basic personality traits map onto moral judgments of fairness-related actions? Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(3), 710–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytug, Z. G., Kern, M. C., & Dilchert, S. (2018a). Multicultural experience: Development and validation of a multidimensional scale. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 65, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aytug, Z. G., Rua, T., Brazeal, D. V., Almaraz, J. A., & González, C. B. (2018b). A socio-cultural approach to multicultural experience: Why interactions matter for creative thinking but exposures don’t. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 64, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, S., & Jiménez-Leal, W. (2017). It’s not right but it’s permitted: Wording effects in moral judgement. Judgment and Decision Making, 12(3), 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, F. K., Paolini, S., Pedersen, A., Hornsey, M. J., Radke, H. R. M., Harwood, J., Rubin, M., & Sibley, C. G. (2012). The contact caveat: Negative contact predicts increased prejudice more than positive contact predicts reduced prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(12), 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, H. C., Bolyanatz, A., Crittenden, A. N., Fessler, D. M. T., Fitzpatrick, S., Gurven, M., Henrich, J., Kanovsky, M., Kushnick, G., Pisor, A., Scelza, B. A., Stich, S., von Rueden, C., Zhao, W., & Laurence, S. (2016). Small-scale societies exhibit fundamental variation in the role of intentions in moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(17), 4688–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartels, D. M., Bauman, C. W., Cushman, F. A., Pizarro, D. A., & McGraw, A. P. (2015). Moral judgment and decision making. In G. Keren, & G. Wu (Eds.), The Wiley blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making (pp. 478–515). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J., Galinsky, A. D., & Maddux, W. W. (2014). Does travel broaden the mind? Breadth of foreign experiences increases generalized trust. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5(5), 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. X., Lam, B. C. P., Hui, B. P. H., Ng, J. C. K., Mak, W. W. S., Guan, Y., Buchtel, E. E., Tang, W. C. S., & Lau, V. C. Y. (2016). Conceptualizing psychological processes in response to globalization: Components, antecedents, and consequences of global orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(2), 302–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X., Leung, A. K. y., Yang, D. Y. J., Chiu, C. Y., Li, Z. Q., & Cheng, S. Y. Y. (2016). Cultural threats in culturally mixed encounters hamper creative performance for individuals with lower openness to experience. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47(10), 1321–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. Y., & Leung, A. K. Y. (2012). Revisiting the multicultural experience-creativity link: The effects of perceived cultural distance and comparison mind-set. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 4(4), 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C. Y., & Hong, Y. Y. (2013). Social psychology of culture. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Cipolletti, H., McFarlane, S., & Weissglass, C. (2016). The moral foreign-language effect. Philosophical Psychology, 29(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A., Foucart, A., Hayakawa, S., Aparici, M., Apesteguia, J., Heafner, J., & Keysar, B. (2014). Your morals depend on language. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e94842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisp, R. J., & Turner, R. N. (2011). Cognitive adaptation to the experience of social and cultural diversity. Psychological Bulletin, 137(2), 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, P. G. (2016). Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 66, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, F. (2008). Crime and punishment: Distinguishing the roles of causal and intentional analyses in moral judgment. Cognition, 108(2), 353–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y., & Savani, K. (2020). From variability to vulnerability: People exposed to greater variability judge wrongdoers more harshly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 118(6), 1101–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M., van Prooijen, J. W., Wu, S., & van Lange, P. A. M. (2021). Culture, status, and hypocrisy: High-status people who don’t practice what they preach are viewed as worse in the United States than China. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(1), 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endicott, L., Bock, T., & Narvaez, D. (2003). Moral reasoning, intercultural development, and multicultural experiences: Relations and cognitive underpinnings. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(4), 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, D. R. (1992). Judging the morality of business practices: The influence of personal moral philosophies. Journal of Business Ethics, 11(5–6), 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, F. J., Sutherland, D., Lee, J. Y., Liu, Y., & Pan, Y. (2019). Challenges for foreign companies in China: Implications for research and practice. Asian Business and Management, 18(4), 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funder, D. C. (2006). Towards a resolution of the personality triad: Persons, situations, and behaviors. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawali, G., & Khattar, T. (2016). The influence of multicultural personality on attitude towards religious diversity among youth. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 42(1), 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geipel, J., Hadjichristidis, C., & Surian, L. (2015). How foreign language shapes moral judgment. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 59, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelfand, M. J., Lyons, S. L., & Lun, J. (2011). Toward a psychological science of globalization. Journal of Social Issues, 67(4), 841–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X., Fang, J., Han, Y., Li, Z., Zhao, M., & Yang, Y. (2019). The influence of moral relativism and disgust on moral intuitive judgment. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(4), 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J. X., Hall, J. A., & Rosenthal, R. (2016). Mini meta-analysis of your own studies: Some arguments on why and a primer on how. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(10), 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, G. P., & Darley, J. M. (2010). The perceived objectivity of ethical beliefs: Psychological findings and implications for public policy. Review of Philosophy and Psychology, 1(2), 161–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, G. P., & Darley, J. M. (2012). Why are some moral beliefs perceived to be more objective than others? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowans, C. (2021). Moral relativism. In E. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab. Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-relativism/ (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Harman, G. (1975). Moral relativism defended. The Philosophical Review, 84(1), 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis, second edition: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, P. L., & Lapsley, D. K. (2009). Persons and situations in the moral domain. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(2), 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horberg, E. J., Oveis, C., & Keltner, D. (2011). Emotions as moral amplifiers: An appraisal tendency approach to the influences of distinct emotions upon moral judgment. Emotion Review, 3(3), 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y., & Zhang, M. (2012). Wen hua “dong tai jian gou” de li lun he zheng ju [Theory and evidence for the “dynamic construction” of culture]. Journal of Southwest University (Social Sciences Edition), 38(4), 83–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X. (2017). Global orientations and moral foundations: A cross-cultural examination among American, Chinese, and international students [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Rutgers University]. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X., Yu, F., & Peng, K. (2018). How does culture affect morality? The perspectives of between-culture variations, within-culture variations, and multiculturalism. Advances in Psychological Science, 26(11), 2081–2090. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahane, G., Everett, J. A. C., Earp, B. D., Farias, M., & Savulescu, J. (2015). “Utilitarian” judgments in sacrificial moral dilemmas do not reflect impartial concern for the greater good. Cognition, 134, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H. (2021). Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 18, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, A. K. Y., Maddux, W. W., Galinsky, A. D., & Chiu, C.-y. (2008). Multicultural experience enhances creativity: The when and how. American Psychologist, 63(3), 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in social science. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F., Chao, M. C., Chen, N. Y., & Zhang, S. (2018). Moral judgment in a business setting: The role of managers’ moral foundation, ideology, and level of moral development. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 35(1), 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J., Galinsky, A. D., & Maddux, W. W. (2015). The dark side of multicultural experiences: Broad multicultural experiences increase dishonesty. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2015(1), 12357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. G., Quoidbach, J., Gino, F., Chakroff, A., Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2017). The dark side of going abroad: How broad foreign experiences increase immoral behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, W. W., & Galinsky, A. D. (2009). Cultural borders and mental barriers: The relationship between living abroad and creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddux, W. W., Lu, J. G., Affinito, S. J., & Galinsky, A. D. (2021). Multicultural experiences: A systematic review and new theoretical framework. Academy of Management Annals, 15(2), 345–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malle, B. F. (2021). Moral Judgments. Annual Review of Psychology, 72, 3.1–3.26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, V. M. (2021). What was globalization? Globalizations, 18(5), 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Narvaez, D., & Hill, P. L. (2010). The relation of multicultural experiences to moral judgment and mindsets. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 3(1), 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, R. E., Sinnott-Armstrong, W., & Sinnott-Armstrong, N. A. (2010). Wording effects in moral judgments. Judgment and Decision Making, 5(7), 547–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G., Cheyne, J. A., Barr, N., Koehler, D. J., & Fugelsang, J. A. (2014). The role of analytic thinking in moral judgements and values. Thinking and Reasoning, 20(2), 188–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaget, J. (1952). The origins of intelligence in children. International University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, T. S., & Holyoak, K. J. (2013). Exposure to moral relativism compromises moral behaviors. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49, 995–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoff, B. (2003). Nature of human development. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shipilov, A., Godart, F. C., & Clement, J. (2017). Which boundaries? How mobility networks across countries and status groups affect the creative performance of organizations. Strategic Management Journal, 38(6), 1232–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L. L., Gino, F., & Bazerman, M. H. (2011). Dishonest deed, clear conscience: When cheating leads to moral disengagement and motivated forgetting. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(3), 330–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J. J., Vitell, S. J., Al-Khatib, J., & Clark, I. (2007). The role of moral intensity and personal moral philosophies in the ethical decision making of marketers: A cross-cultural comparison of China and the United States. Journal of International Marketing, 15(2), 86–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smillie, L. D., Katic, M., & Laham, S. M. (2021). Personality and moral judgment: Curious consequentialists and polite deontologists. Journal of Personality, 89(3), 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadmor, C. T., Hong, Y. Y., Chao, M. M., & Cohen, A. (2018). The tolerance benefits of multicultural experiences depend on the perception of available mental resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(3), 398–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadmor, C. T., Hong, Y. Y., Chao, M. M., Wiruchnipawan, F., & Wang, W. (2012a). Multicultural experiences reduce intergroup bias through epistemic unfreezing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(5), 750–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadmor, C. T., Satterstrom, P., Jang, S., & Polzer, J. T. (2012b). Beyond individual creativity: The superadditive benefits of multicultural experience for collective creativity in culturally diverse teams. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(3), 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenberg, J., & Knobelsdorf, M. (2014). Out of our minds: A review of sociocultural cognition theory. Computer Science Education, 24(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S. J., & King, L. A. (2018). Individual differences in reliance on intuition predict harsher moral judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 114(5), 825–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, A., Burgmer, P., & Mussweiler, T. (2018). Two-faced morality: Distrust promotes divergent moral standards for the self versus others. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(12), 1712–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakunina, E. S., Weigold, I. K., Weigold, A., Hercegovac, S., & Elsayed, N. (2012). The multicultural personality: Does it predict international students’ openness to diversity and adjustment? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(4), 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, L., & Heiphetz, L. (2014). A social cognitive developmental perspective on moral judgment. Behaviour, 151, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaikauskaite, L., Chen, X., & Tsivrikos, D. (2020). The effects of idealism and relativism on the moral judgement of social vs. environmental issues, and their relation to self-reported proenvironmental behaviours. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0239707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zettler, I., & Hilbig, B. E. (2010). Honesty-humility and a person-situation interaction at work. European Journal of Personality, 24(7), 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Study 1 | Study 2 | Study 3 | Study 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 10 | 23.26 | 47 | 33.81 | 48 | 26.82 | 50 | 31.85 | |

| Female | 33 | 76.74 | 92 | 66.19 | 131 | 73.18 | 107 | 68.15 | |

| Education background | |||||||||

| High school or lower | - | - | 2 | 1.44 | 3 | 1.68 | 4 | 2.55 | |

| Junior college | - | - | 4 | 2.88 | 1 | 0.56 | 1 | 0.64 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 43 | 100 | 80 | 57.55 | 73 | 40.78 | 89 | 56.69 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | - | - | 53 | 38.13 | 102 | 56.98 | 63 | 40.13 | |

| Monthly income | |||||||||

| Less than CNY 50,000 | 5 | 11.63 | 30 | 21.58 | 36 | 20.11 | 24 | 15.29 | |

| CNY 50,000–CNY 100,000 | 10 | 23.26 | 45 | 32.37 | 50 | 27.93 | 51 | 32.48 | |

| CNY 100,000–CNY 200,000 | 19 | 44.19 | 38 | 27.34 | 59 | 32.96 | 54 | 34.39 | |

| CNY 200,000–CNY 500,000 | 8 | 18.60 | 21 | 15.11 | 29 | 16.20 | 23 | 14.65 | |

| CNY 500,000–CNY 1 million | 1 | 2.33 | 5 | 3.60 | 4 | 2.23 | 5 | 3.18 | |

| Over CNY 1 million | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.56 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| M ± SD | |||||||||

| Age | 21.44 ± 2.02 | 23.58 ± 4.93 | 23.31 ± 3.40 | 24.18 ± 5.37 | |||||

| Entries | Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RESEA | 90% CI for RESEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 1-factor | 195.71 *** | 27 | 7.25 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.15 | 0.21 | [0.19, 0.24] |

| 2-factor | 48.43 ** | 26 | 1.86 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.08 | [0.04, 0.11] | |

| Duration | 1-factor | 249.02 *** | 27 | 9.22 | 0.74 | 0.65 | 0.13 | 0.24 | [0.22, 0.27] |

| 2-factor | 89.00 *** | 26 | 3.42 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.06 | 0.13 | [0.10, 0.16] | |

| Breadth | 1-factor | 296.29 *** | 27 | 1.97 | 0.66 | 0.54 | 0.21 | 0.27 | [0.24, 0.30] |

| 2-factor | 55.21 *** | 26 | 2.12 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.05 | 0.09 | [0.06, 0.12] |

| Variables | M (SD) | α | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ME a | 0.00 (0.83) | 0.90 | - | |||||

| 2. MI a | 0.00(0.86) | 0.94 | 0.48 *** | |||||

| 3. Moral judgment | 8.89 (0.99) | 0.84 | −0.04 | −0.23 ** | ||||

| 4. Gender | 0.34 (0.48) | - | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13 | |||

| 5. Age | 23.58 (4.93) | - | 0.09 | 0.17 * | −0.04 | 0.06 | ||

| 6. Education | 3.32 (0.61) | - | 0.23 ** | 0.19 * | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.18 * | |

| 7. Income | 2.47 (1.10) | - | 0.31 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.10 | 0.04 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| Variables | Model 1 β (SE) | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.10 (0.61) | 0.05 (0.65) | −0.48 (0.63) | −0.36 (0.65) | −0.37 (0.64) |

| Control variable | |||||

| Gender | −0.27 (0.18) | −0.28 (0.18) | −0.28 (0.18) | −0.27 (0.18) | −0.26 (0.18) |

| Age | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) |

| Education | −0.01 (0.14) | −0.01 (0.15) | 0.05 (0.14) | 0.03 (0.14) | 0.05 (0.15) |

| Income | −0.08 (0.08) | −0.07 (0.08) | −0.01 (0.08) | −0.02 (0.08) | −0.03 (0.08) |

| Key predictors | |||||

| ME | −0.02 (0.09) | 0.09 (0.10) | 0.15 (0.11) | ||

| MI | −0.25 (0.09) ** | −0.29 (0.10) ** | −0.33 (0.10) ** | ||

| ME × MI | 0.12 (0.09) | ||||

| R2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiao, L.; Yang, Y.; Xu, Y. Multicultural Interactions Decrease the Tendency to View Any Act as Unambiguously Wrong: The Moderating Role of Moral Flexibility. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060782

Jiao L, Yang Y, Xu Y. Multicultural Interactions Decrease the Tendency to View Any Act as Unambiguously Wrong: The Moderating Role of Moral Flexibility. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):782. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060782

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiao, Liying, Ying Yang, and Yan Xu. 2025. "Multicultural Interactions Decrease the Tendency to View Any Act as Unambiguously Wrong: The Moderating Role of Moral Flexibility" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060782

APA StyleJiao, L., Yang, Y., & Xu, Y. (2025). Multicultural Interactions Decrease the Tendency to View Any Act as Unambiguously Wrong: The Moderating Role of Moral Flexibility. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 782. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060782