Hear, See, Do (Nothing)? An Integrative Framework of Co-Workers’ Reactions to Interpersonal Workplace Mistreatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. A Much-Needed Integrated Co-Workers’ Perspective on IWM

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Individual Factors

4.1.1. Perceived Responsibility

4.1.2. Emotion and Affect

4.1.3. Personal Characteristics

4.2. Contextual Factors

4.2.1. Social Relationships

4.2.2. Risks and Cost Considerations

4.2.3. Workplace Characteristics

4.2.4. Target Characteristics

4.2.5. Perpetrator and IWM Characteristics

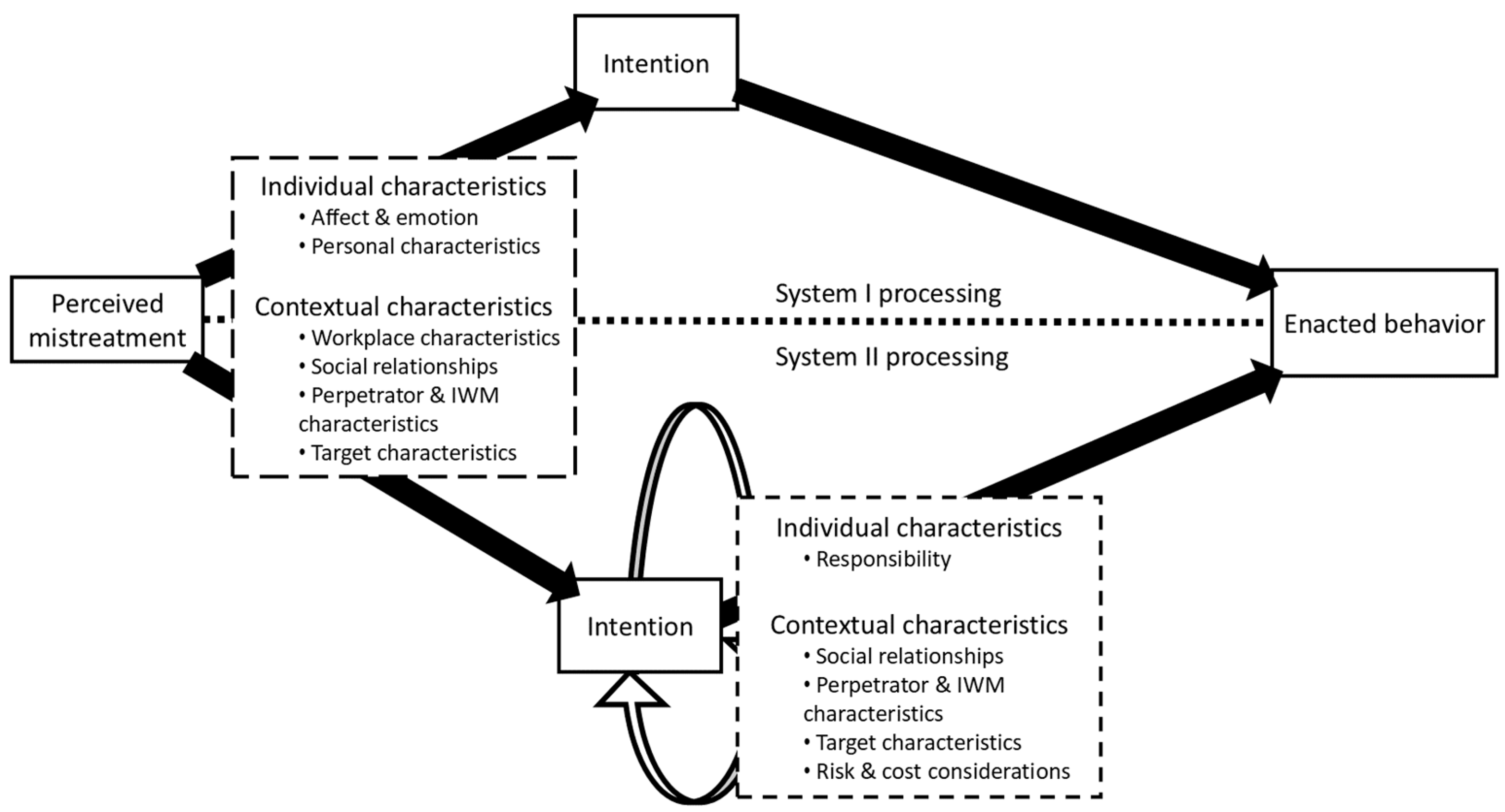

4.3. Towards an Integrative Framework

4.3.1. From Intention to Response: Dual Processing Accounts

4.3.2. System I Processing

4.3.3. System II Processing

5. Discussion

5.1. General Discussion

5.2. A Future Research Agenda

5.3. Practical Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AET | Affective Events Theory |

| HR | Human Resources |

| ILO | International Labor Organization |

| IWM | Interpersonal Workplace Mistreatment |

| SERV | Sociaal-Economische Raad van Vlaanderen |

References

- *Aftab, S., Saleem, I., & Mansor, N. N. A. (2024). How and when does witnessing incivility lead to psychological distress in family-owned bank employees? Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, 17(2), 514–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, L. M., Pearson, C. M., & Pearson, M. (2009). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquino, K., & Thau, S. (2009). Workplace victimization: Aggression from the target’s perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(7), 717–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Azeem, M. U., Haq, I. U., De Clercq, D., & Liu, C. (2024). Why and when do employees feel guilty about observing supervisor ostracism? The critical roles of observers’ silence behavior and leader–member exchange quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 194, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, C., Conway, P. M., & van Heugten, K. (2021). The contribution of organizational factors to workplace bullying, emotional abuse, and harassment. In P. D’Cruz, & E. Noronha (Eds.), Handbooks of workplace bullying, emotional abuse and harassment (vol. 2, pp. 3–28). Pathways of job-related negative behaviour. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V. L. (2011). Who will help prevent sexual violence: Creating an ecological model of bystander intervention. Psychology of Violence, 1(3), 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyard, V. L. (2024). Have we fully tapped the potential of bystander intervention? Shelve it or sustain it? Psychology of Violence, 14(6), 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barclay, L. J., Skarlicki, D. P., & Pugh, S. D. (2005). Exploring the role of emotions in injustice perceptions and retaliation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 629–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastick, T. (1982). Intuition: How we think and act. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Batson, C. D., Kennedy, C. L., Nord, L. A., Stocks, E. L., Fleming, D. A., Marzette, C. M., Lishner, D. A., Hayes, R. E., Kolchinsky, L. M., & Zerger, T. (2007). Anger at unfairness: Is it moral outrage? European Journal of Social Psychology, 37(6), 1272–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Báez-León, C., Moreno-Jiménez, B., Aguirre-Camacho, A., & Olmos, R. (2016). Factors influencing intention to help and helping behaviour in witnesses of bullying in nursing settings. Nursing Inquiry, 23(4), 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancourt, H. (1990). An attribution-empathy model of helping behavior: Behavioral intentions and judgements of help-giving. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16(3), 573–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowes-Sperry, L., & O’Leary-Kelly, A. M. (2005). To act or not to act: The dilemma faced by sexual harassment observers. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 288–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Bowes-Sperry, L., & Powell, G. N. (1999). Observers’ reactions to social-sexual behavior at work: An Ethical decision making perspective. Journal of Management, 25(6), 779–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowling, N. A., & Beehr, T. A. (2006). Workplace harassment from the Victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(5), 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Chen, A., Yan, L., & Yoon, M. Y. (2024). What happens after anti-asian racism at work? A moral exclusion perspective on coworker confrontation and mechanisms. Journal of Applied Psychology, 110(3), 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Chen, C., Qin, X., Yam, K. C., & Wang, H. (2021). Empathy or schadenfreude? Exploring observers’ differential responses to abusive supervision. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36, 1077–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Chen, S. C., & Liu, N. T. (2019). When and how vicarious abusive supervision leads to bystanders’ supervisor-directed deviance: A moderated–mediation model. Personnel Review, 48(7), 1734–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Collazo, J. L., & Kmec, J. A. (2019). Organizational emphasis on inclusion as a cultural value and third-party response to sexual harassment. Employee Relations, 41(1), 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2003). Raising voice, risking retaliation: Events following interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 8(4), 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Coyne, I., Gopaul, A. M., Campbell, M., Pankász, A., Garland, R., & Cousans, F. (2019). Bystander responses to bullying at work: The role of mode, type and relationship to target. Journal of Business Ethics, 157(3), 813–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M. A., & George, E. (2023). The why and how of the integrative review. Organizational Research Methods, 26(1), 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, M. A., Jeroen, S., & van Knippenberg, D. (2021). The theory crisis in management research: Solving the right problem. Academy of Management Review, 46(4), 667–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *D’Cruz, P., & Noronha, E. (2011). The limits to workplace friendship: Managerialist HRM and bystander behaviour in the context of workplace bullying. Employee Relations, 33(3), 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Desrumaux, P., Jeoffrion, C., Bouterfas, N., De Bosscher, S., & Boudenghan, M. C. (2018). Workplace bullying: How do bystanders’ emotions and the type of bullying influence their willingness to help? Nordic Psychology, 70(4), 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Desrumaux, P., Machado, T., Vallery, G., & Michel, L. (2016). Bullying of the manager and employees’ prosocial or antisocial behaviors: Impacts on equity, responsibility judgments, and witnesses’ help-giving. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 9(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, L. Y., & Bogart, S. M. (2025). Mapping the mistreatment landscape: An integrative review and reconciliation of workplace mistreatment constructs. Journal of Organizational Behavior. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanani, L. Y., & LaPalme, M. L. (2019). It’s not personal: A review and theoretical integration of research on vicarious workplace mistreatment. Journal of Management, 45(6), 2322–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Diekmann, K. A., Walker, S. D. S., Galinsky, A. D., & Tenbrunsel, A. E. (2013). Double victimization in the workplace: Why observers condemn passive victims of sexual harassment. Organization Science, 24(2), 614–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einarsen, S. Ê. (1999). The nature and causes of bullying at work. International Journal of Manpower, 20(1/2), 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S., Pacini, R., Denes-Raj, V., & Heier, H. (1996). Individual differences in intuitive–experiential and analytical–rational thinking styles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J. S. B. T. (2003). In two minds: Dual-process accounts of reasoning. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 7(10), 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J. S. B. T. (2008). Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J. S. B. T. (2010). Intuition and reasoning: A dual-process perspective. Psychological Inquiry, 21(4), 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. S. B. T., & Stanovich, K. E. (2013). Dual-process theories of higher cognition: Advancing the debate. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8(3), 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Feng, Z., & Savani, K. (2023). When do employees help abused coworkers? It depends on their own experience with abusive supervision. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 34, 374–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Fernando, D., & Kenny, E. (2023). The identity impact of witnessing selective incivility: A study of minority ethnic professionals. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 96(1), 56–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Fiori, M., Krings, F., Kleinlogel, E., & Reich, T. (2016). Whose side are you on? Exploring the role of perspective taking on third-party’s reactions to workplace deviance. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 38(6), 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- *Gabriel, A. S., Chawla, N., Rosen, C. C., Lee, Y. E., Koopman, J., & Wong, E. M. (2024). Who speaks up when harassment is in the air? A within-person investigation of ambient harassment and voice behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(1), 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Ghumman, S., Ryan, A. M., & Park, J. S. (2016). Religious harassment in the workplace: An examination of observer intervention. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(2), 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Ghumman, S., Ryan, A. M., & Park, J. S. (2024). Who helps who? The role of stigma dimensions in harassment intervention. Journal of Business Ethics, 189(1), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Gligor, D. M., Bozkurt, S., & Gligor, N. M. (2023). External observers’ reactions to abusive supervision in the workplace: The impact of racial differences. Journal of Management and Organization, 29(3), 522–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Gloor, J. L., Okimoto, T. G., Li, X., Gazdag, B. A., & Ryan, M. K. (2023). How identity impacts bystander responses to workplace mistreatment. Journal of Management, 50(7), 2641–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Hall, T. K., & Dhanani, L. Y. (2023). Cloaked in kindness: Bystander responses to witnessed benevolent and hostile sexism. Sex Roles, 89(11–12), 658–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Haq, I. U., Azeem, M. U., Rasheed, M., & Anwar, F. (2024). How does witnessing coworker ostracism differentially elicit victim-directed help and enacted ostracism: The mediating roles of compassion and schadenfreude, moderated by dispositional envy. Journal of Business Research, 179, 114708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M. A., Brett, C. E., Johnson, W., & Deary, I. J. (2016). Personality stability from age 14 to age 77 years. Psychology and Aging, 31(8), 862874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Haynes-Baratz, M. C., Bond, M. A., Allen, C. T., Li, Y. L., & Metinyurt, T. (2022). Challenging gendered microaggressions in the academy: A social–ecological analysis of bystander action among faculty. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 15(4), 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- *Hellemans, C., Dal Cason, D., & Casini, A. (2017). Bystander helping behavior in response to workplace bullying. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 76(4), 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershcovis, M. S. (2011). “Incivility, social undermining, bullying …oh my!”: A call to reconcile constructs within workplace aggression research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(3), 499–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hershcovis, M. S., Cortina, L. M., & Robinson, S. L. (2020). Social and situational dynamics surrounding workplace mistreatment: Context matters. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(8), 699–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Hershcovis, M. S., Neville, L., Reich, T. C., Christie, A. M., Cortina, L. M., & Shan, J. V. (2017). Witnessing wrongdoing: The effects of observer power on incivility intervention in the workplace. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 142, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Huang, J., Guo, G., Tang, D., Liu, T., & Tan, L. (2019). An eye for an eye? Third parties’ silence reactions to peer abusive supervision: The mediating role of workplace anxiety, and the moderating role of core self-evaluation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2022). Violence and harassment in the world of work: A guide on Convention No. 190 and Recommendation No. 206. International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- *Jacobson, R. K., & Eaton, A. A. (2018). How organizational policies influence bystander likelihood of reporting moderate and severe sexual harassment at work. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 30(1), 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Jensen, J. M., & Raver, J. L. (2021). A policy capturing investigation of bystander decisions to intervene against workplace incivility. Journal of Business and Psychology, 36(5), 883–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). How perceptions of fairness can change: A dynamic model of organizational justice. Organizational Psychology Review, 3(2), 138–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, E. E., Farina, A., Hastorf, A. H., Markus, H., Miller, D. T., & Scott, R. A. (1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- *Jönsson, S., & Muhonen, T. (2022). Factors influencing the behavior of bystanders to workplace bullying in healthcare—A qualitative descriptive interview study. Research in Nursing and Health, 45(4), 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Jungert, T., & Holm, K. (2022). Workplace incivility and bystanders’ helping intentions. International Journal of Conflict Management, 33(2), 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Kay, A. A., Masters-Waage, T. C., Reb, J., & Vlachos, P. A. (2023). Mindfully outraged: Mindfulness increases deontic retribution for third-party injustice. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 176, 104249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. K., & Kim, Y. (2023). Multilevel causal attributions on transboundary risk: Effects on attributions of responsibility, psychological distance, and policy support. Risk Analysis, 43(7), 1310–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Kondziolka, D., & Liau, L. M. (2021). Sexual harassment in neurosurgery: #ustoo. Journal of Neurosurgery, 135(2), 339–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, J. C., & Searle, F. (2023). Does bystander intervention training work? When employee intentions and organisational barriers collide. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(3–4), 2934–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasater, K., Mood, L., Buchwach, D., & Dieckmann, N. F. (2015). Reducing incivility in the workplace: Results of a three-part educational intervention. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 46(1), 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- *Liang, Y., & Park, Y. A. (2025). A spectrum of bystander actions: Latent profile analysis of sexual harassment intervention behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S., & Cortina, L. M. (2005). Interpersonal mistreatment in the workplace: The interface and impact of general incivility and sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 483–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Lin, X., & Loi, R. (2021). Punishing the perpetrator of incivility: The differential roles of moral identity and moral thinking orientation. Journal of Management, 47(4), 898–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Liu, P., An, X., & Li, X. (2022). You are an outsider! How and when observed leader incivility affect hospitality employees’ social categorization and deviant behavior. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 106, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Lutgen-Sandvik, P. (2006). Take this job and…: Quitting and other forms of resistance to workplace bullying. Communication Monographs, 73(4), 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutgen-Sandvik, P., & Fletcher, C. V. (2013). Conflict motivations and tactics of targets, bystanders, and bullies: A thrice-told tale of workplace bullying. In The SAGE handbook of conflict communication: Integrating theory, research, and practice (pp. 349–376). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, M., & van den Bos, K. (2009). An affective-experiential perspective on reactions to fair and unfair events: Individual differences in affect intensity moderated by experiential mindsets. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *MacCurtain, S., Murphy, C., O’Sullivan, M., MacMahon, J., & Turner, T. (2018). To stand back or step in? Exploring the responses of employees who observe workplace bullying. Nursing Inquiry, 25(1), e12207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Madden, C., & Loh, J. (2020). Workplace cyberbullying and bystander helping behaviour. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(19), 2434–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitlis, S., Vogus, T. J., & Lawrence, T. B. (2013). Sensemaking and emotion in organizations. Organizational Psychology Review, 3(3), 222–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Dasborough, M. T. (2011). Attribution theory in the organizational sciences: A case of unrealized potential. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32(1), 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P., & Flood, M. (2012). Bystander approaches to sexual harassment in the workplace. Available online: https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/publications/bystander-approaches-sexual-harassment-workplace (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- *Meglich, P., Porter, T., & Day, N. (2020). Does sexual orientation of bullying target influence bystander response? The Irish Journal of Management, 39(1), 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). Whistleblowing in organizations: An examination of correlates of whistleblowing intentions, actions, and retaliation. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(3), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Mitchell, M. S., Vogel, R. M., & Folger, R. (2015). Third parties’ reactions to the abusive supervision of coworkers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1040–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghavvemi, S., Salleh, N. A. M., Sulaiman, A., & Abessi, M. (2015). Effect of external factors on intention-behaviour gap. Behaviour and Information Technology, 34(12), 1171–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Mulder, R., Bos, A. E. R., Pouwelse, M., & van Dam, K. (2017). Workplace mobbing: How the victim’s coping behavior influences bystander responses. Journal of Social Psychology, 157(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Mulder, R., Pouwelse, M., Lodewijkx, H., & Bolman, C. (2008). Emoties en de intentie tot helpen van omstanders bij pesten op het werk: De invloed van waargenomen verantwoordelijkheid en besmettingsdreiging. Gedrag & Organisatie, 21(1), 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- *Mulder, R., Pouwelse, M., Lodewijkx, H., Bos, A. E. R., & van Dam, K. (2016). Predictors of antisocial and prosocial behaviour of bystanders in workplace mobbing. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 26(3), 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuman, J. H., & Baron, R. A. (1998). Workplace violence and workplace aggression: Evidence concerning specific forms, potential causes, and preferred targets. Journal of Management, 24(3), 391–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newark, D. A. (2014). Indecision and the construction of self. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 125(2), 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K., Niven, K., & Hoel, H. (2020). ‘I could help, but …’: A dynamic sensemaking model of workplace bullying bystanders. Human Relations, 73(12), 1718–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K., Randall, R., Holten, A. L., & González, E. R. (2010). Conducting organizational-level occupational health interventions: What works? Work and Stress, 24(3), 234–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, J., & Aquino, K. (2011). A model of third parties’ morally motivated responses to mistreatment in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 36(3), 526–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *O’Reilly, J., Aquino, K., & Skarlicki, D. (2016). The lives of others: Third parties’ responses to others’ injustice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(2), 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Østvik, K., & Rudmin, F. (2001). Bullying and hazing among Norwegian army soldiers: Two studies of prevalence, context, and cognition. Military Psychology, 13(1), 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Paull, M., Omari, M., D’Cruz, P., & Güneri Çangarli, B. (2020). Bystanders in workplace bullying: Working university students’ perspectives on action versus inaction. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 58(3), 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paull, M., Omari, M., & Standen, P. (2012). When is a bystander not a bystander? A typology of the roles of bystanders in workplace bullying. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 50(3), 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Pierce, C. A., Broberg, B. J., McClure, J. R., & Aguinis, H. (2004). Responding to sexual harassment complaints: Effects of a dissolved workplace romance on decision-making standards. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 95(1), 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouwelse, M., Mulder, R., & Mikkelsen, E. G. (2018). The role of bystanders in workplace bullying: An overview of theories and empirical research. In P. D’Cruz, E. Noronha, E. Baillien, B. Catley, K. P. Harlos, & A. Hogh (Eds.), Handbooks of workplace bullying, emotional abuse and harassment (Vol. 2, pp. 1–39). Pathways of job-related negative behaviour. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Priesemuth, M. (2013). Stand up and speak up: Employees’ prosocial reactions to observed abusive supervision. Business and Society, 52(4), 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Priesemuth, M., & Schminke, M. (2019). Helping thy neighbor? Prosocial reactions to observed abusive supervision in the workplace. Journal of Management, 45(3), 1225–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Rae, K., & Neall, A. M. (2022). Human resource professionals’ responses to workplace bullying. Societies, 12(6), 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, T. C., & Hershcovis, M. S. (2015). Observing workplace incivility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(1), 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, T. C., Hershcovis, S. M., Lyubykh, Z., Niven, K., Parker, S. K., & Stride, C. B. (2021). Observer reactions to workplace mistreatment: It’s a matter of perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 26(5), 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Rosette, A. S., Carton, A. M., Bowes-Sperry, L., & Hewlin, P. F. (2013). Why do racial slurs remain prevalent in the workplace? Integrating theory on intergroup behavior. Organization Science, 24(5), 1402–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotundo, M., Nguyen, D. H., & Sackett, P. R. (2001). A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 914–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, U., Roesch, S. C., Greitemeyer, T., & Weiner, B. (2004). A meta-analytic review of help giving and aggression from an attributional perspective: Contributions to a general theory of motivation. Cognition and Emotion, 18(6), 815–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Ryan, A. M., & Wessel, J. L. (2012). Sexual orientation harassment in the workplace: When do observers intervene? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 510–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salancik, G. R., & Pfeffer, J. (1978). A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23(2), 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilpzand, P., De Pater, I. E., & Erez, A. (2016). Workplace incivility: A review of the literature and agenda for future research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37, 57–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran, P., & Webb, T. L. (2016). The intention–behavior gap. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(9), 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffey, A. N., & Tindale, T. T. (1992). Perceptions of sexual harassment in the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22(19), 1502–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- *Sinclair, S. (2021). Bystander reactions to workplace incivility: The role of gender and discrimination claims. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 17(1), 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Skarlicki, D. P., & Rupp, D. E. (2010). Dual processing and organizational justice: The role of rational versus experiential processing in third-party reactions to workplace mistreatment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociaal-Economische Raad van Vlaanderen (SERV). (2023). Vlaamse werkbaarheidsmonitor werknemers: Meting 2023. Available online: https://www.serv.be/stichting/project/vlaamse-werkbaarheidsmonitor-werknemers-meting-2023 (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Stanovich, K. E. (1999). Who is rational?: Studies of individual differences in reasoning. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tenbrunsel, A. E., Diekmann, K. A., Wade-Benzoni, K. A., & Bazerman, M. H. (2010). The ethical mirage: A temporal explanation as to why we are not as ethical as we think we are. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Thompson, N. J., Carter, M., Crampton, P., Burford, B., & Illing, J. (2020). Workplace bullying in healthcare: A qualitative analysis of bystander experiences. The Qualitative Report, 25(11), 3993–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, E. B., & Tully, E. C. (2014). Empathy as a risky strength: A multilevel examination of empathy and risk for internalizing disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 1547–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human Resource Development Review, 4(3), 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Umphress, E. E., Simmons, A. L., Folger, R., Ren, R., & Bobocel, R. (2013). Observer reactions to interpersonal injustice: The roles of perpetrator intent and victim perception. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(3), 327–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kleef, G. A., Wanders, F., Stamkou, E., & Homan, A. C. (2015). The social dynamics of breaking the rules: Antecedents and consequences of norm-violating behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuren, C. M., Tims, M., & de Lange, A. H. (2021). A systematic review of negative work behavior: Toward an integrated definition. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 726973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranjes, I., Griep, Y., Fortin, M., & Notelaers, G. (2023a). Dynamic and multi-party approaches to interpersonal workplace mistreatment research. Group and Organization Management, 48(4), 995–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranjes, I., Vander Elst, T., Griep, Y., De Witte, H., & Baillien, E. (2023b). What goes around comes around: How perpetrators of workplace bullying become targets themselves. Group and Organization Management, 48(4), 1135–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E. U., Ames, D. R., & Blais, A. R. (2004). ‘How do i choose thee? let me count the ways’: A textual analysis of similarities and differences in modes of decision-making in China and the United States. Management and Organization Review, 1(1), 87–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Weber, M., Koehler, C., & Schnauber-Stockmann, A. (2019). Why should i help you? Man up! Bystanders’ gender stereotypic perceptions of a cyberbullying incident. Deviant Behavior, 40(5), 585–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Wei, W., Chen, H., Feng, J., & Li, J. (2023). Helpful or hurtful? A study on the behavior choice of bystanders in the context of abusive supervision. International Journal of Conflict Management, 34(3), 623–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, cause and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, H. M., Suckow, K., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). Effects of justice conditions on discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(5), 786–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Yu, H. H. (2023). Reporting workplace discrimination: An exploratory analysis of bystander behavior. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 44(3), 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Yu, Y., Li, Y., Xu, S. (Tracy), & Li, G. (2022). It’s not just the victim: Bystanders’ emotional and behavioural reactions towards abusive supervision. Tourism Management, 91, 104506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Zhang, Y., Liu, X., & Chen, W. (2020). Fight and flight: A contingency model of third parties’ approach-avoidance reactions to peer abusive supervision. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(6), 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Zhao, K., Yan, Y., Zhou, Z. E., Xiao, S., Shan, D., & Iqbal, M. (2025). Punish or help? Third parties’ constructive responses to witnessed workplace incivility: The role of political skill. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- *Zhou, X., Fan, L., Cheng, C., & Fan, Y. (2021). When and why do good people not do good deeds? Third-party observers’ unfavorable reactions to negative workplace gossip. Journal of Business Ethics, 171(3), 599–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bastiaensen, C.V.M.; Baillien, E.; Brebels, L. Hear, See, Do (Nothing)? An Integrative Framework of Co-Workers’ Reactions to Interpersonal Workplace Mistreatment. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060764

Bastiaensen CVM, Baillien E, Brebels L. Hear, See, Do (Nothing)? An Integrative Framework of Co-Workers’ Reactions to Interpersonal Workplace Mistreatment. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):764. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060764

Chicago/Turabian StyleBastiaensen, Caroline Veronique Marijke, Elfi Baillien, and Lieven Brebels. 2025. "Hear, See, Do (Nothing)? An Integrative Framework of Co-Workers’ Reactions to Interpersonal Workplace Mistreatment" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060764

APA StyleBastiaensen, C. V. M., Baillien, E., & Brebels, L. (2025). Hear, See, Do (Nothing)? An Integrative Framework of Co-Workers’ Reactions to Interpersonal Workplace Mistreatment. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 764. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060764