Do People Judge Sexual Harassment Differently Based on the Type of Job a Victim Has?

Abstract

1. Do People Judge Sexual Harassment Differently Based on the Type of Job a Victim Has?

1.1. Gender Norms and Perceptions of Sexual Harassment

1.2. Prototypes and Perceptions of Sexual Harassment

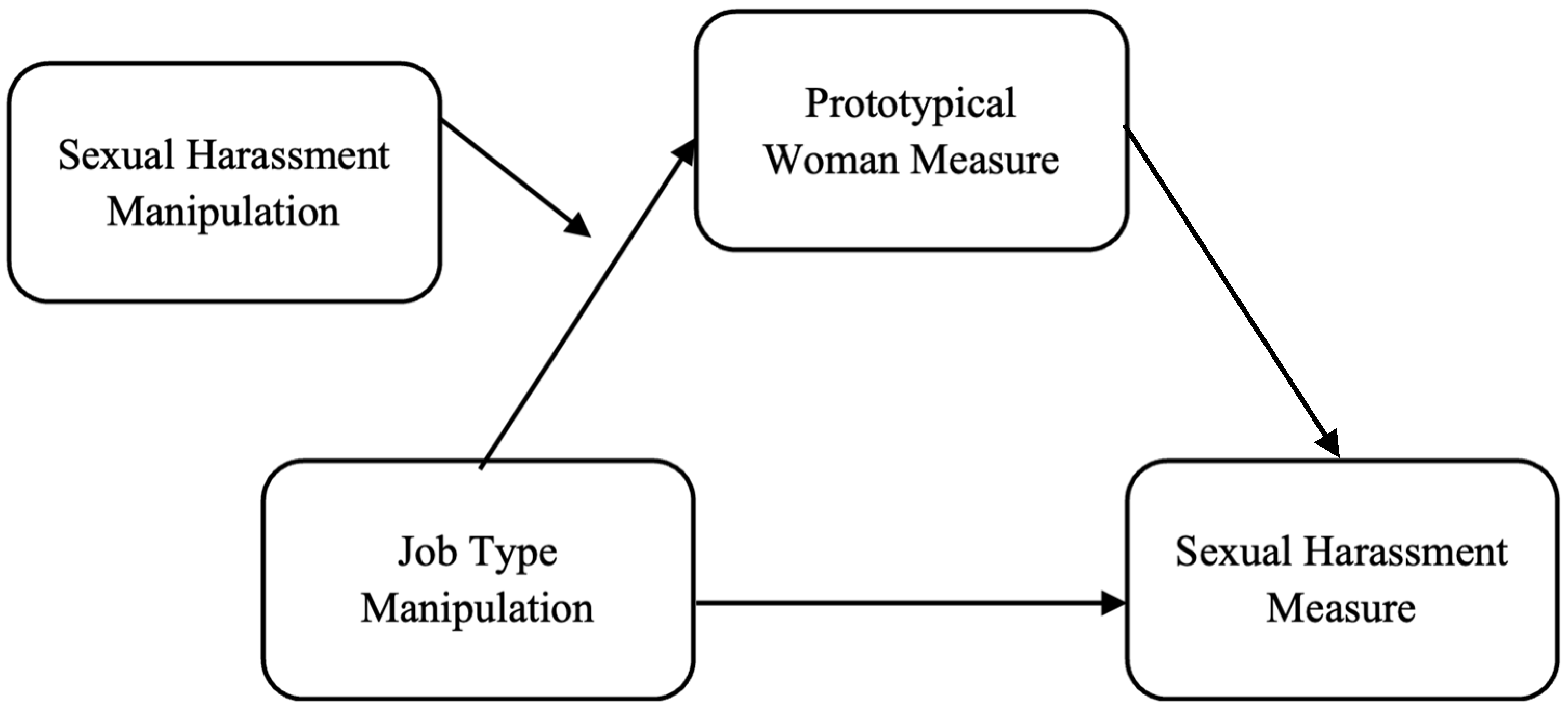

1.3. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures and Manipulation

2.2.1. Jennifer’s Manipulation

2.2.2. Sara’s Manipulation

2.2.3. Brenda’s Manipulation

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sexual Harassment Measure

2.3.2. Blame Victim Measure

2.3.3. Prototypical Woman Measure

2.4. Data Cleaning

3. Results

3.1. Manipulation Checks

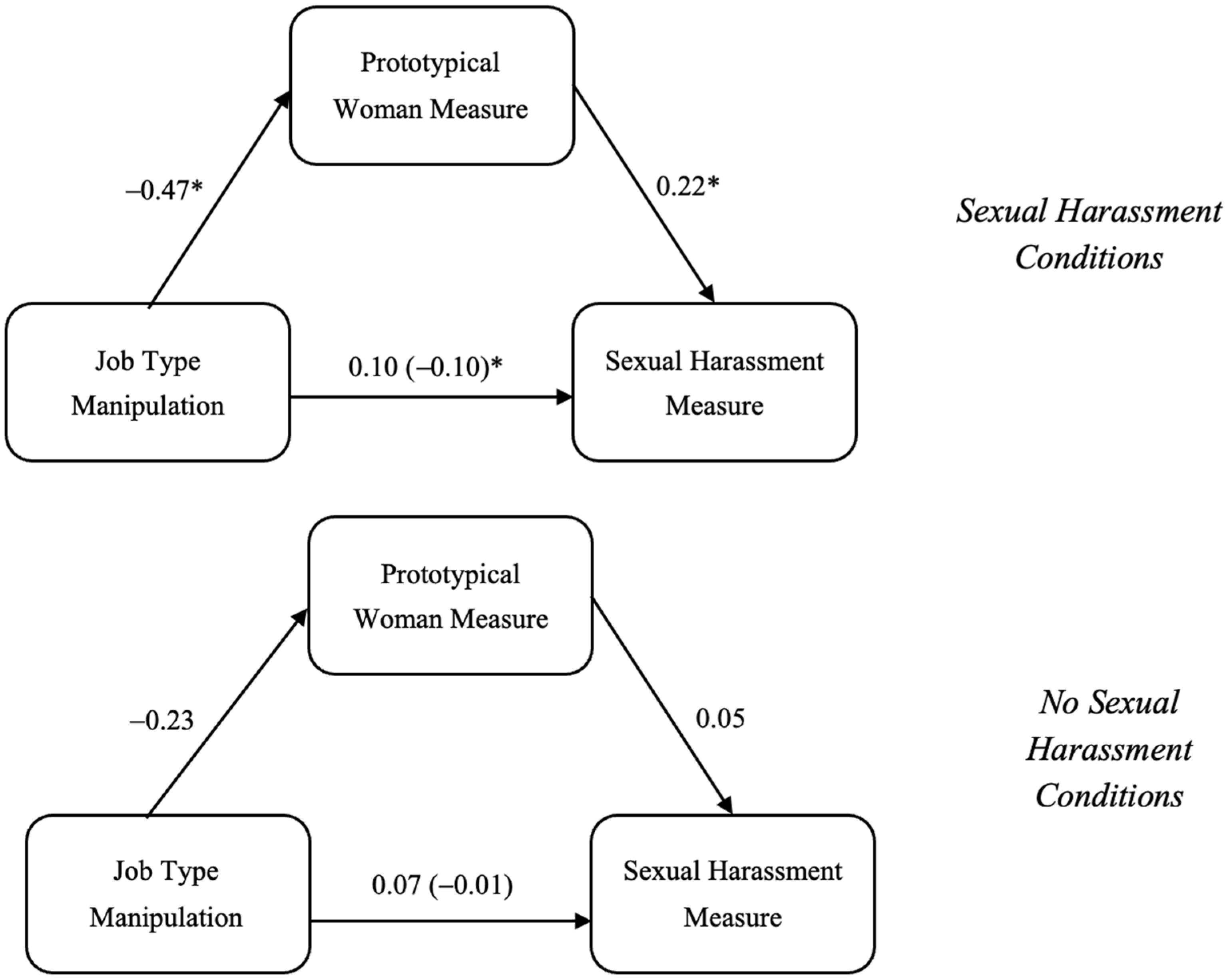

3.2. Jennifer Conditions Results

3.3. Sara Conditions Results

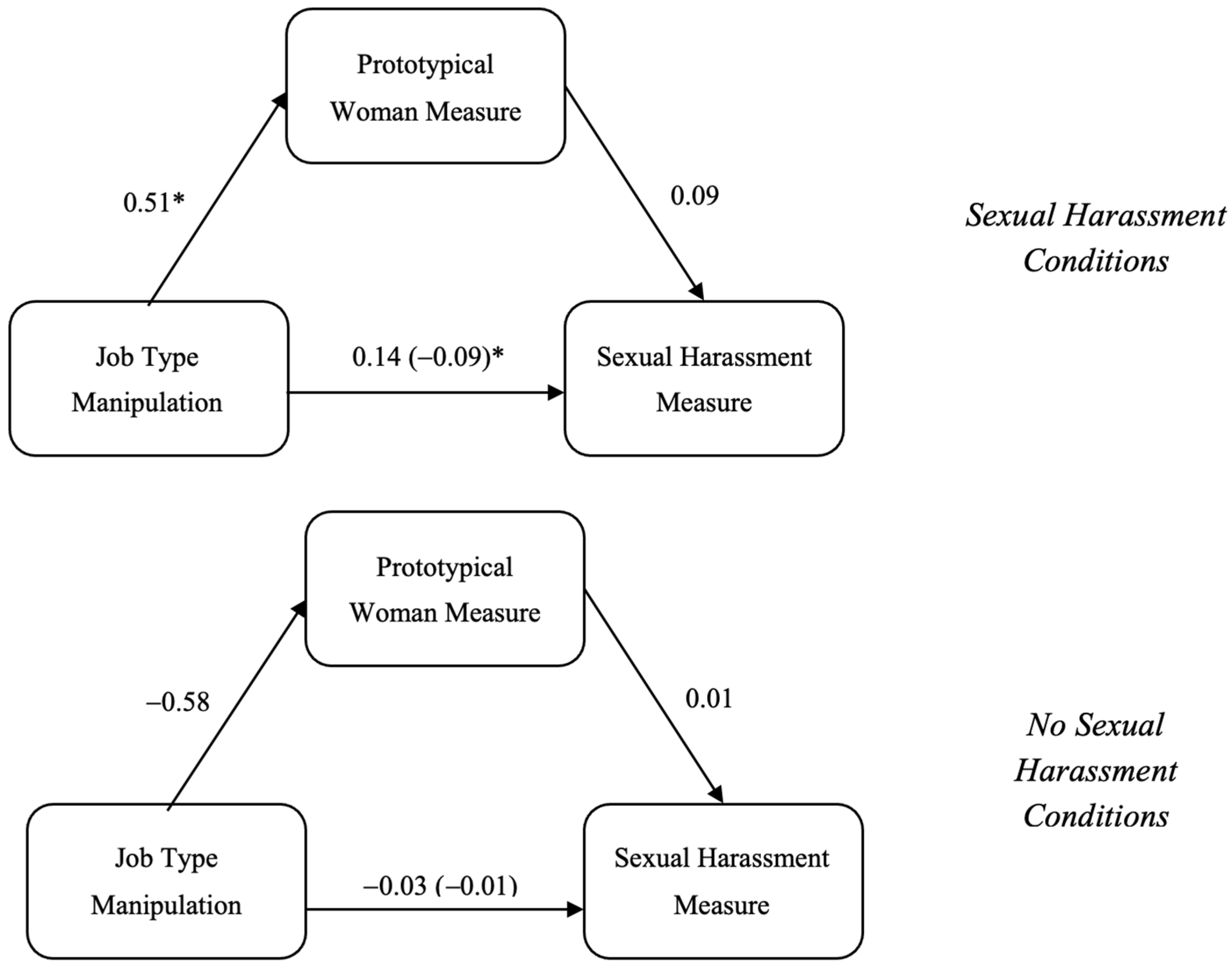

3.4. Brenda Conditions Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications for the Study

4.2. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The specific jobs for the feminine and masculine manipulation were decided on based on pilot data and similarity in setting. For example, police officer was considered a masculine job and teacher was considered a feminine job. Therefore, we manipulated teacher and school officer to the setting itself (Simon and Smith Elementary) could remain consistent between conditions. |

| 2 | There were no significant interactions, therefore, no simple slop analyses were conducted. |

References

- Au, S. Y., Dong, M., & Tremblay, A. (2024). How much does workplace sexual harassment hurt firm value? Journal of Business Ethics, 190(4), 861–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandt-Law, B., Cheek, N. N., Goh, J. X., Sinclair, S., & Kaiser, C. R. (2021, February 9–13). #WhatAboutUs: The neglect of non-prototypical sexual harassment victims [Paper presentation]. Society for Personality and Social Psychology 22nd Annual Meeting, Online Event. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, A., & Sharma, B. (2011). Gender differences in perception of workplace sexual harassment among future professionals. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 20(1), 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, E., Popkin, R., Roodzant, E., Jaworski, B., & Temkin, S. M. (2023). Gender as a social and structural variable: Research perspectives from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Translational Behavioral Medicine, 14(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, P. (2007). Perceptions of sexual harassment. Sociological Inquiry, 63, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendixen, M., & Kennair, L. E. (2017). When less is more: Psychometric properties of Norwegian short-forms of the ambivalent sexism scales (ASI and AMI) and the Illinois rape myth acceptance (IRMA) scale. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 58, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdahl, J. L. (2007a). Harassment based on sex: Protecting social status in the context of gender hierarchy. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 641–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdahl, J. L. (2007b). The sexual harassment of uppity women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdahl, J. L., & Moore, C. (2006). Workplace harassment: Double jeopardy for minority women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(2), 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brassel, S. T., Settles, I. H., & Buchanan, N. T. (2019). Lay (mis) perceptions of sexual harassment toward transgender, lesbian, and gay employees. Sex Roles, 80, 76–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, T. L., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2008). Rape myth acceptance and sexual harassment perceptions: A study of university students. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(11), 2893–2912. [Google Scholar]

- Burt, M. R. (1980). Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. K.-S., Lam, C. B., Chow, S. Y., & Cheung, S. F. (2008). Examining the job-related, psychological, and physical outcomes of workplace sexual harassment: A meta-analytic review. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32(4), 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheryan, S., Ziegler, S. A., Montoya, A. K., & Jiang, L. (2017). Why are some STEM fields more gender balanced than others? Psychological Bulletin, 143(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cislaghi, B., & Heise, L. (2020). Gender norms and social norms: Differences, similarities and why they matter in prevention science. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(2), 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, H., Lawrence, S., Wilson, E., Sweeting, F., & Poate-Joyner, A. (2023). ‘No one likes a grass’ Female police officers’ experience of workplace sexual harassment: A qualitative study. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 25(2), 183–195. [Google Scholar]

- Denmark, F. L. (2004). Gender, overview. In C. D. Spielberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of applied psychology (pp. 71–84). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2012). Social role theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A. W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology: Volume two (pp. 458–476). SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2006). Sexual harassment. Available online: https://www.eeoc.gov/sexual-harassment (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Fitzgerald, L. F., & Cortina, L. M. (2018). Sexual harassment in work organizations: A view from the 21st century. In C. B. Travis, J. W. White, A. Rutherford, W. S. Williams, S. L. Cook, & K. F. Wyche (Eds.), APA handbook of the psychology of women: Perspectives on women’s private and public lives (pp. 215–234). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, L. F., Gelfand, M. J., & Drasgow, F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(4), 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A. S., Butts, M. M., Yuan, Z., Rosen, R. L., & Sliter, M. T. (2018). Further understanding incivility in the workplace: The effects of gender, agency, and communion. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(4), 362–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaucher, D., Friesen, J., & Kay, A. C. (2011). Evidence that gendered wording in job advertisements exists and sustains gender inequality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(1), 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., Manganelli, A. M., Pek, J. C. X., Huang, L.-L., Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., Castro, Y. R., D’Avila Pereira, M. L., Willemsen, T. M., Brunner, A., Six-Materna, I., Wells, R., & Glick, P. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, P., Wilk, K., & Perreault, M. (1995). Images of occupations: Components of gender and status in occupational stereotypes. Sex Roles, 32(9–10), 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, J. X., Bandt-Law, B., Cheek, N. N., Sinclair, S., & Kaiser, C. R. (2022). Narrow prototypes and neglected victims: Understanding perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122(5), 873–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, J., Johnson, C., & Lopez, R. (2001). Sexual Harassment in the workplace: Exploring the effects of attractiveness on perception of harassment. Sex Roles, 45, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutworth, M., & Howard, M. (2019). Improving sexual harassment training effectiveness with climate interventions. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 12, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, R., Moss, A. J., Jaffe, S. N., Rosenzweig, C., LItman, L., & Robinson, J. (2023). Introducing connect by Cloud Research: Advancing online participant recruitment in the digital age. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. In Methodology in the social sciences (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heilman, M. E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M. E., & Caleo, S. (2018). Gender bias in the workplace: A review of the literature and a new direction for research. Journal of Social Issues, 74(3), 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilman, M. E., Caleo, S., & Manzi, F. (2024). Women at work: Pathways from gender stereotypes to gender bias and discrimination. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 165–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibino, Y., Hitomi, Y., Kambayashi, Y., & Nakamura, H. (2009). Exploring factors associated with the incidence of sexual harassment of hospital nurses by patients. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 41(2), 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J., & Schnurr, S. (2005). Politeness, humor and gender in the workplace: Negotiating norms and identifying contestation. Journal of Politeness Research Language Behaviour Culture, 1(1), 139–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, C. R., Bandt-Law, B., Cheek, N. N., & Schachtman, R. (2022). Gender prototypes shape perceptions of and responses to sexual harassment. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 31(3), 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulibert, D., Reidt, I., & O’Brien, L. (2025). Is that really sexual harassment? The effect of a victim’s sexual orientation on how people view a sexual harassment claim. Journal of Homosexuality, 72(1), 20–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, R. F., Leshin, R. A., Moty, K., Foster-Hanson, E., & Rhodes, M. (2022). How race and gender shape the development of social prototypes in the United States. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(8), 1956–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonsway, K. A., Cortina, L. M., & Magley, V. J. (2008). Sexual harassment mythology: Definition, conceptualization, and measurement. Sex Roles, 58, 599–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M. P., & Hardman, L. (2005). Attitudes and perceptions of workers to sexual harassment. The Journal of Social Psychology, 145(6), 719–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, K., & Griffith, J. (2019). #Ustoo: How I-O psychologists can extend the conversation on sexual harassment and sexual assault through workplace training. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 12(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Women’s Law Center. (2016). Let her work: Protecting black women’s employment rights. National Women’s Law Center. [Google Scholar]

- Okatta, C., Ajayi, F., & Olawale, O. (2024). Enhancing organizational performance through diversity and inclusion initiatives: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 6, 734–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pao, C. (2023). Masculinity and femininity by racial identification: Racialized differences in responses to self-rated gender scales for cisgender men and women. Socius, 9(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, K. (2018). Women in majority-male workplaces report higher rates of gender discrimination. Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/03/07/women-in-majority-male-workplaces-report-higher-rates-of-gender-discrimination/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Purdie-Vaughns, V., & Eibach, R. P. (2008). Intersectional invisibility: The distinctive advantages and disadvantages of multiple subordinate-group identities. Sex Roles, 59, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, K., & Heaton, K. (2023). Antecedents to sexual harassment of women in selected male-dominated occupations: A systematic review. Workplace Health & Safety, 71(8), 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch, E. (1978). Principles of categorization. In Cognition and categorization (pp. 27–48). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2008). Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacco, D. F., Brown, M., & May, H. D. (2021). Not taking a joke: The influence of target status, sex, and age on reactions to workplace humor. Psychological Reports, 124(3), 1316–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvaggio, A. N., Streich, M., Hopper, J. E., & Pierce, C. A. (2011). Why do fools fall in love (at work)? Factors associated with the incidence of workplace romance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(4), 906–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtman, R., Gallegos, J., & Kaiser, C. R. (2023). Gender prototypes hinder bystander intervention in women’s sexual harassment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 51(6), 1007–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlick, C. J. R., Ellis, R. J., Etkin, C. D., Greenberg, C. C., Greenberg, J. A., Turner, P. L., Buyske, J., Hoyt, D. B., Nasca, T. J., Bilimoria, K. Y., & Hu, Y. Y. (2021). Experiences of gender discrimination and sexual harassment among residents in general surgery programs across the US. JAMA Surgery, 156(10), 942–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2018). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E. L., Dovidio, J. F., & West, T. V. (2014). Lost in the categorical shuffle: Evidence for the social non-prototypicality of black women. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(3), 370–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vault Careers. (2018). The 2018 Vault office romance survey results. Available online: http://www.vault.com/blog/workplace-issues/2018-vault-office-romance-survey-results/ (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Wakelin, A., & Long, K. M. (2003). Effects of victim gender and sexuality on attributions of blame to rape victims. Sex Roles, 49, 477–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiener, R. L., Hurt, L., Russell, B., Mannen, K., & Gasper, C. (1997). Perceptions of sexual harassment: The effects of gender, legal standard, and ambivalent sexism. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worke, M. D., Koricha, Z. B., & Debelew, G. T. (2021). Perception and experiences of sexual harassment among women working in hospitality workplaces of Bahir Dar city, Northwest Ethiopia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 21, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Number of Participants |

|---|---|

| Men | 207 |

| Women | 199 |

| Other Gender | 8 |

| White | 272 |

| Black/African American | 55 |

| Asian/Asian American | 40 |

| Indigenous Nation/Native American | 1 |

| Latinx/Hispanic American | 30 |

| Multiracial/Other Race | 16 |

| Age | 37.03 (11.50) |

| Political Ideology | 3.17 (1.75) |

| Feminine Condition Mean (SD) | Masculine Condition Mean (SD) | t-Test | Cohen’s d CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jennifer Conditions | 3.55 (1.34) | 4.91 (1.54) | 9.75 * | [0.75, 1.15] |

| Sara Conditions | 2.96 (1.28) | 4.26 (1.41) | 9.89 * | [0.76, 1.17] |

| Brenda Conditions | 2.97 (1.29) | 3.97 (1.27) | 8.00 * | [0.58, 0.98] |

| F-Test | p-Value | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Harassment Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 603.84 | <0.001 | 0.592 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 0.02 | 0.891 | 0.000 |

| Interaction | 0.02 | 0.890 | 0.000 |

| Blame of Victim Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 11.64 | <0.001 | 0.027 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 0.81 | 0.370 | 0.002 |

| Interaction | 0.01 | 0.929 | 0.000 |

| Prototypical Woman Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 7.46 | 0.007 | 0.018 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 12.37 | <0.001 | 0.029 |

| Interaction | 0.82 | 0.366 | 0.002 |

| Sexual Harassment Condition | No Sexual Harassment Condition | Feminine Condition | Masculine Condition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jennifer Conditions | ||||

| Sexual Harassment Measure | 5.32 (1.45) | 2.23 (1.09) | 3.76 (1.97) | 3.78 (2.05) |

| Blame of Victim Measure | 1.74 (1.00) | 2.11 (1.21) | 1.97 (1.09) | 1.88 (1.16) |

| Prototypical Woman Measure | 4.96 (1.03) | 4.67 (1.17) | 5.00 (1.00) | 4.63 (1.19) |

| Sarah Conditions | ||||

| Sexual Harassment Measure | 6.63 (0.78) | 1.66 (1.03) | 4.15 (2.63) | 4.19 (2.67) |

| Blame of Victim Measure | 1.50 (0.78) | 1.43 (0.95) | 1.42 (0.84) | 1.51 (0.89) |

| Prototypical Woman Measure | 5.15 (1.06) | 4.88 (1.06) | 5.28 (0.99) | 4.74 (1.10) |

| Brenda Conditions | ||||

| Sexual Harassment Measure | 6.50 (0.98) | 1.61 (1.14) | 4.10 (2.64) | 4.08 (2.70) |

| Blame of Victim Measure | 1.50 (0.84) | 1.66 (1.07) | 1.52 (0.88) | 1.64 (1.04) |

| Prototypical Woman Measure | 5.18 (0.93) | 5.04 (0.93) | 5.17 (0.97) | 5.06 (1.02) |

| F-Test | p-Value | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Harassment Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 3097.64 | <0.001 | 0.881 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 0.11 | 0.737 | 0.000 |

| Interaction | 0.93 | 0.335 | 0.001 |

| Blame of Victim Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 0.54 | 0.462 | 0.001 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 1.15 | 0.285 | 0.003 |

| Interaction | 0.03 | 0.875 | 0.001 |

| Prototypical Woman Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 7.42 | 0.007 | 0.018 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 28.81 | <0.001 | 0.065 |

| Interaction | 0.41 | 0.521 | 0.001 |

| F-Test | p-Value | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual Harassment Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 2199.67 | <0.001 | 0.842 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 0.06 | 0.814 | 0.000 |

| Interaction | 0.16 | 0.694 | 0.000 |

| Blame of Victim Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 2.87 | 0.091 | 0.007 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 1.42 | 0.234 | 0.003 |

| Interaction | 0.11 | 0.740 | 0.000 |

| Prototypical Woman Measure | |||

| Sexual Harassment Manipulation | 1.96 | 0.162 | 0.005 |

| Job Type Manipulation | 1.28 | 0.258 | 0.003 |

| Interaction | 1.25 | 0.265 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Halfon, C.G.; McCray, D.; Kulibert, D. Do People Judge Sexual Harassment Differently Based on the Type of Job a Victim Has? Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060757

Halfon CG, McCray D, Kulibert D. Do People Judge Sexual Harassment Differently Based on the Type of Job a Victim Has? Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):757. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060757

Chicago/Turabian StyleHalfon, Carolyne Georgiana, Destiny McCray, and Danica Kulibert. 2025. "Do People Judge Sexual Harassment Differently Based on the Type of Job a Victim Has?" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060757

APA StyleHalfon, C. G., McCray, D., & Kulibert, D. (2025). Do People Judge Sexual Harassment Differently Based on the Type of Job a Victim Has? Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 757. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060757