Enhancing Prospective Teachers’ Professional Development Through Shared Collaborative Lesson Planning

Abstract

1. Introduction

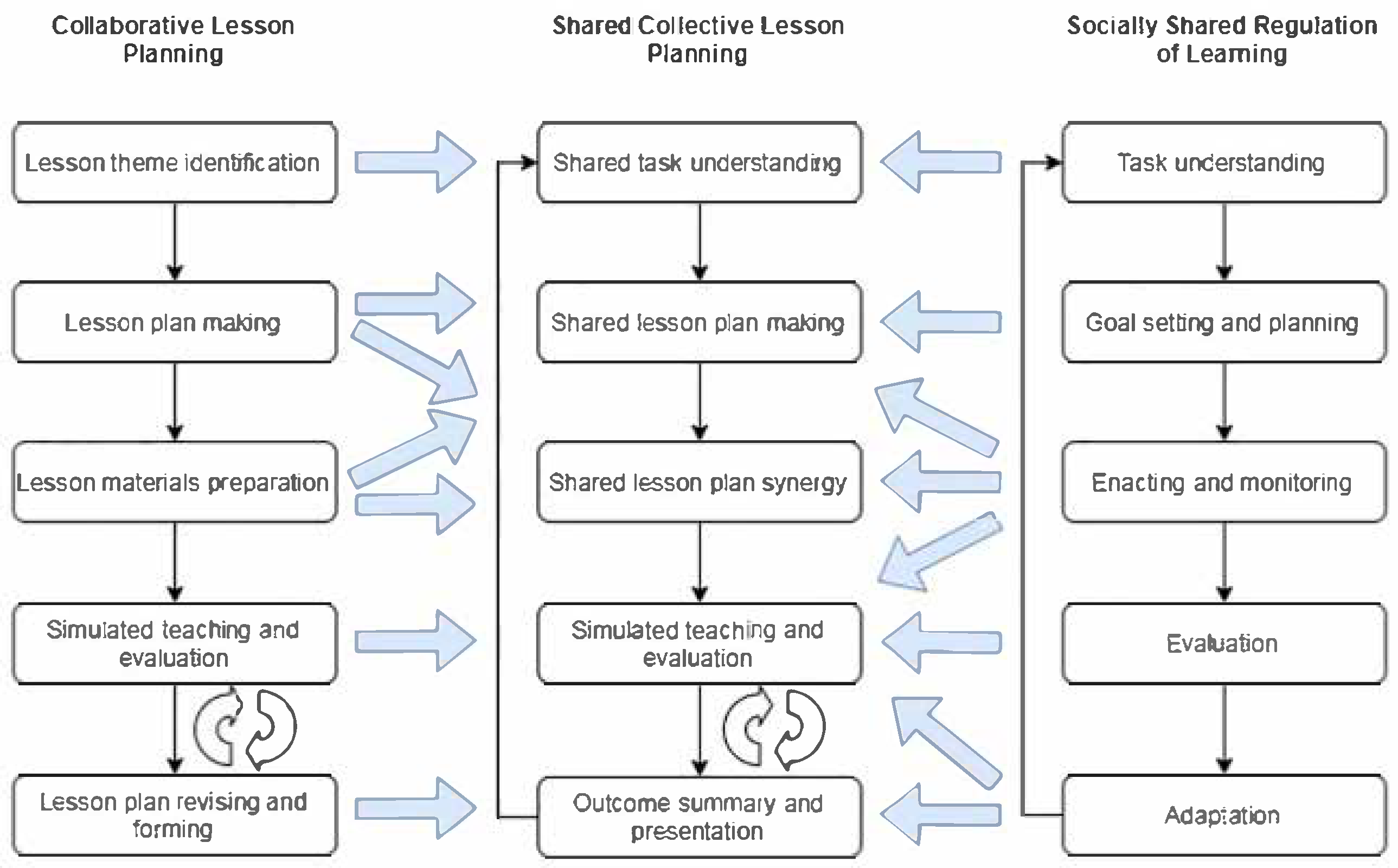

1.1. Collaborative Lesson Planning

1.2. Socially Shared Regulation of Learning (SSRL)

1.3. The Shared Collaborative Lesson Planning (SCLP) Procedure

1.4. Research Goal and Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Online Collaborative Learning Platform for Supporting the SCLP

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Shared Task Understanding

2.3.2. Shared Lesson Plan Making

2.3.3. Shared Lesson Plan Synergy

2.3.4. Simulated Teaching and Evaluation

2.3.5. Outcome Summary and Presentation

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. The First Round of SCLP

3.1.1. Shared Task Understanding in the First Round

3.1.2. Shared Plan Making in the First Round

- PT A: I wish a comfortable and efficient atmosphere where everyone can contribute effectively to the SCLP.

- PT B: Each member should be able to share their ideas and perspectives without any concerns. The group leader should facilitate the progress of collaborative learning and lesson planning activities, while another member should be responsible for documenting important discussions and events.

- PT C: I hope each member can freely express their opinions and listen to others with an open mind, contributing to a healthy collaborative learning environment.

- PT D: Everyone should have the opportunity to speak out their own views on the topics and issues.

- PT E: I wish a harmonious, relaxed, and efficient collaborative learning and teaching atmosphere.

- Co-construct a complete shared lesson plan.

- Prepare a lesson plan presentation document.

- Collect and process accessible teaching resources.

- Improve collaborative lesson planning and teaching skills.

- Achieve the shared goals, with each member presenting the lesson plan in a personalized manner.

3.1.3. Shared Lesson Plan Synergy in the First Round

- When one group member was distracted by the rain outside the window, another member gently reminded them to refocus on the group discussion and summarized what had been discussed.

- PT A: We can go through the whole process and divide it into parts. Then we each choose a part to write.

- PT B: Do we need to create a file on the online collaborative documentation platform (Shimo)?

- PT A: Of course.

- PT C: was watching a video on her mobile phone.

- PT D: Please stop watching.

- PT E: There is one more document to write, but we cannot finish it now.

- PT B: Let’s concentrate on working out the lesson plan first.

- PT C: Sure, let’s get started.

3.1.4. Simulated Teaching and Evaluation in the First Round

3.1.5. Outcome Summary and Presentation in the First Round

3.1.6. Summaries on the First Round of SCLP

- Group A: Due to unfamiliarity with the lesson content, we encountered difficulties in integrating the principles of teaching with content knowledge, such as how to enable teachers to adhere strictly to the instructional norms and at the same time have a high level of mastery of subject knowledge. To address this problem, our group tried to divide the tasks to allow each member to focus on specific areas of content. However, there were arguments regarding the logical order in which the knowledge points should be organized, which led to delays in lesson planning. Some group members also strayed from the topics. Finally, we reached a consensus on the lesson topic after extensive discussion and negotiation in the second stage of SCLP.

- Group B: Our group encountered several technical challenges due to a lack of sufficient supporting materials. We had to search for the packages and related materials by ourselves. Two members took primary responsibility for gathering the items and managed to obtain the required information. Subsequently, our group had a discussion to determine the best way to implement the project.

- Group C: Determining the lesson topic proved to be a challenge, as five members suggested five lesson topics. We initiated several discussion activities to finally confirm. Another issue was related to the hardware failure. The recording and playback equipment in the micro-teaching classroom unexpectedly malfunctioned, and it took much time to coordinate with the technicians to resolve the issue.

- Group A: Our group engaged in a heated discussion about whether to provide students with opportunities to experience and write teaching cases. Each member presented their personal views in an attempt to persuade others. Despite these differences, the SCLP process in our group was generally well-managed. When deviations from the topic or slow progress occurred, the group leader promptly found ways to adapt to the situation.

- Group B: Disagreements arose during our discussions, particularly regarding our understanding of the evaluation criteria. We reached a consensus through negotiation and careful consideration. When progress stalled, we chose to take short breaks to discuss something interesting to refresh our minds and then go back to the collaborative tasks.

- Group C: We encountered a lack of unity in the arrangement of learning activities. However, through negotiation, we reached a unified agreement. Nonetheless, we only conducted a few reflection activities during the SCLP process. Therefore, we had to schedule more additional time for further discussions, which impacted the overall effectiveness of the SCLP to some extent.

3.2. The Second Round of SCLP

3.2.1. Changes in the Second Round

3.2.2. Shared Task Understanding in the Second Round

- “Each of us proposed a lesson topic individually, and we then discussed and agreed upon the lesson topic for our shared lesson plan.”

- “We began by exploring the supporting technologies in the teaching environment and deliberating on what would be appropriate to teach given the available tools. The interactive whiteboards in the micro-teaching classrooms offer a space for students to write without contaminating the physical environment, thereby facilitating lesson content delivery.”

- Group D: Member A and Member B in our group excelled in code writing and instructional evaluation. Member C specialized in debugging codes and facilitating interactions in teaching and learning. Member D was skilled in instructional design and presentation, while Member E was proficient in organizing learning activities and tasks. Each member was expected to have foundational subject knowledge as well as knowledge of artificial intelligence.

- Group E: Member A in our group was proficient in searching for and preparing instructional resources. Member B could be a lead instructional designer. Member C specialized in knowledge synthesis and content technology. Member D was good at instructional skills, and Member E was familiar with the application of CSCL tools. We were required to be familiar with the software and hardware in the teaching environment and how to integrate the technologies into teaching. Additionally, we needed to have a deep understanding of the textbook content.

3.2.3. Shared Plan Making in the Second Round

- PT A (Leader): “The only thing we left in the Instructional Resources and Environment section is the hardware device description?”

- PT B: “Right.”

- PT C: “Should we divide the overall task again?”

- PT A: “Yes, let’s make it more detailed.”

- PT B: “I think we set too many learning activities in our plan.”

- PT D: “That is why I think the activities are intensive.”

- PT C: “Yes, the schedule is full. We only have 45 min to teach and these activities may take up much time.”

- PT D: “But I felt very tired now…”

- PT B: “So… what shall we do next?”

- PT A: “Come on everyone! Let us rearrange the tasks and our lesson plans.”

- PT C: “Sure. I believe you two (pointing to PT D and PT E) can take on the redesign work.”

3.2.4. Shared Lesson Plan Synergy in the Second Round

- PT B: Do you think we should incorporate the two tasks into the Exploration and Practice section (a section in the lesson plan)?

- PT C: I’m not sure. The latter two modules are complex, and it would be more complicated if we add the tasks there.

- PT A: I don’t believe we can articulate the tasks adequately. As future teachers, we lack familiarity with both the teaching content and the underlying mechanisms.

- PT B: Alright…

- PT D: The main issue is that we don’t have enough time to explain these tasks in one lesson.

- PT A: However, the challenge is that we cannot explain these tasks clearly. Experiential tasks are difficult to describe with concrete terms. Students may only gain a superficial understanding. They may fail to fully grasp the tasks after knowing the theoretical explanations. For example, they might understand that an input, such as a photo, can generate an output, but what they really want to know is the process—how do we get from X to Y? Explaining that process thoroughly requires a significant amount of time.

- PT B: Indeed, that is a very difficult task.

3.2.5. Simulated Teaching and Evaluation in the Second Round

3.2.6. Outcome Summary and Presentation in the Second Round

- Group D: We mainly encountered two challenges. First, we were unfamiliar with some operations of the interactive whiteboard and screen-switching function at the very beginning of SCLP. We attempted to address this challenge via repeated attempts in the micro-teaching classroom and by learning from another group. Second, we experienced disagreements regarding the instructional design (content selection and design intention), the selection of the scope of knowledge planned to be taught, and the key points. We spent a certain amount of time preparing the related knowledge and CSCL tools, and acquired inspiration from other good online cases.

- Group E: We encountered three challenges. First, when we attempted to transfer the PowerPoint slides to the interactive whiteboard, some of the charts displayed with messy codes. Fortunately, the built-in drawing function of the whiteboard helped us solve the problem. Second, in the design stage, we had difficulties selecting the suitable conditions. The continuity and fitness of conditions needed to be carefully considered when designing a branching structure diagram. We made some revisions and organized discussions to accomplish this task. Third, the video designed for the Introduction section was too lengthy. A group member edited the video and picked the piece that perfectly fit with the planned lesson time.

3.2.7. Experiences in the Two Rounds of SCLP

- “I definitely believe the SCLP is beneficial to our teaching and lesson planning, as it allows us to actively engage with other members and receive immediate feedback to improve our teaching skills and techniques.”

- “Overall, the SCLP activities enhanced my teaching abilities and the application of CSCL tools in teaching. Initially, I had a limited understanding of the teaching content, which affected my participation in the lesson planning activities. However, as I became more familiar with the content and relevant materials, I felt more confident in contributing to the lesson planning and simulated teaching.”

- “The atmosphere for collaboration was relaxed and harmonious, which encourages me to express my viewpoints more freely. A comfortable collaborative learning environment can definitely promote the interaction and communication among members and can improve the effectiveness of the SCLP.”

- “The atmosphere was both lively and orderly. It motivates us to generate new ideas and opinions, and facilitated our progress for completing the tasks and lesson planning.”

- “We actively applied some CSCL tools in the SCLP. However, we also thoughtfully considered the impact of the tools on our teaching and the need to use them. While the effective use of the tools can improve our efficiency for lesson planning and the teaching and learning, this is contingent upon mastering the technical aspects of the tools. Without such proficiency, the application and integration of CSCL tools could have a negative effect on both teaching and learning performance.”

- “Personally, I advocate the integration of instructional technology. As a future information technology teacher, it is important to utilize CSCL tools appropriately in teaching and learning activities and to continuously seek more effective ways to apply and integrate them successfully into teaching and learning practices.”

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Group Task Understanding Questionnaire

- What lesson topics do you chose for collaborative lesson planning?

- How do you reach a consensus when choosing the group lesson topic?

- What strengths do your group members demonstrate?

- Please indicate the specific tasks assigned to each member.

- What knowledge and skills are needed for the lesson topic and content of the shared lesson plan?

- What available CSCL tools and teaching resources do you plan to apply to complete the tasks?

- What knowledge and skills do you believe are necessary to successfully complete the shared lesson plan?

- What challenges do you anticipate encountering with your group members during the shared collaborative lesson planning?

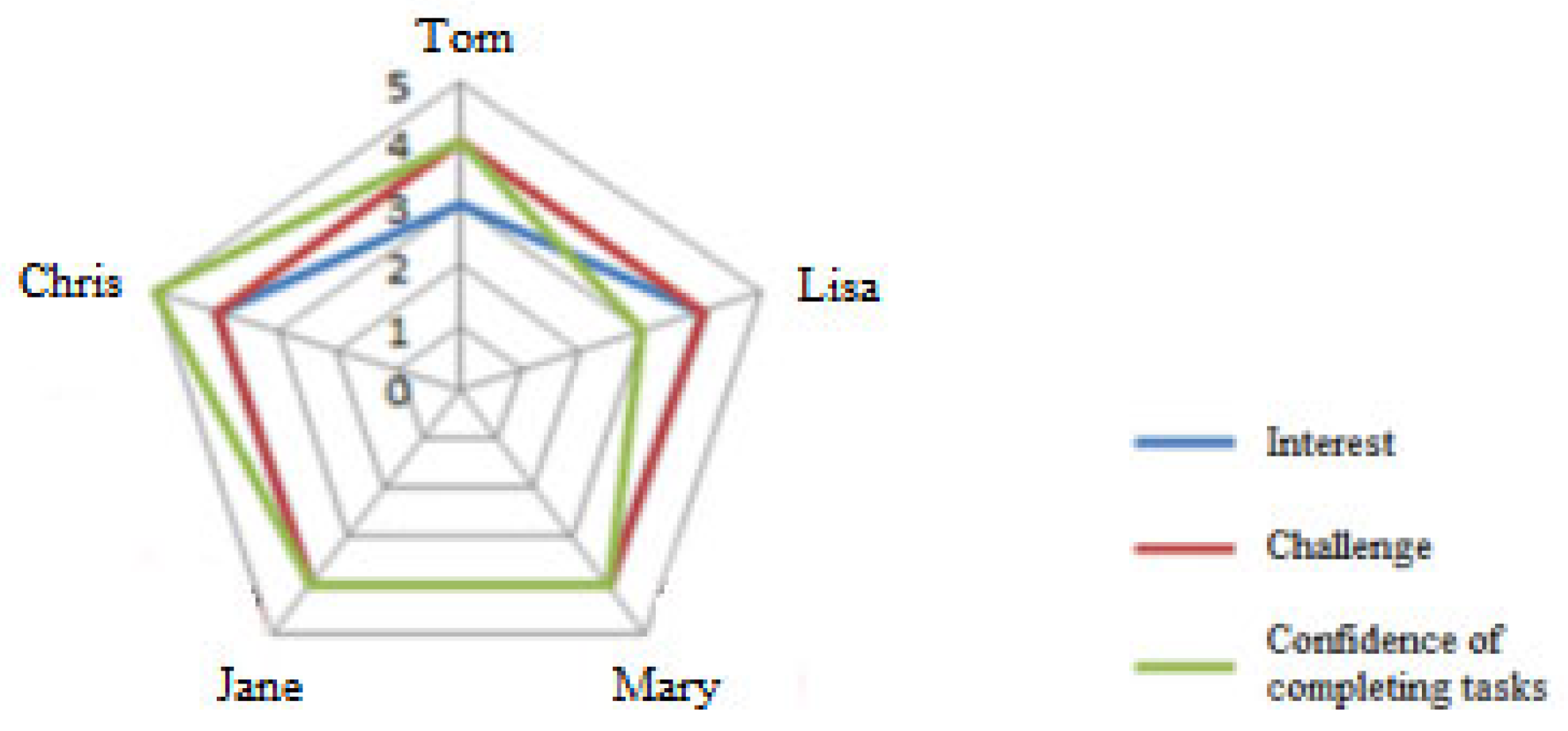

Appendix B. Individual Initial Status Questionnaire

- Are you interested in participating in the shared collaborative lesson planning activities?

- Please explain the reasons that you are interested or not interested in the activities.

- Please estimate of the possibility of your successful completion of all shared collaborative lesson planning activities.

A. 0–20% B. 20–40% C. 40–60% D. 60–80% E. 80–100% - What type of collaborative environment do you expect to be conducive to effective collaborative lesson planning?

- What basic knowledge and skills are considered necessary for effective shared collaborative lesson planning?

- Do you believe you already possess the knowledge and skills? What aspects do you think need improvement?

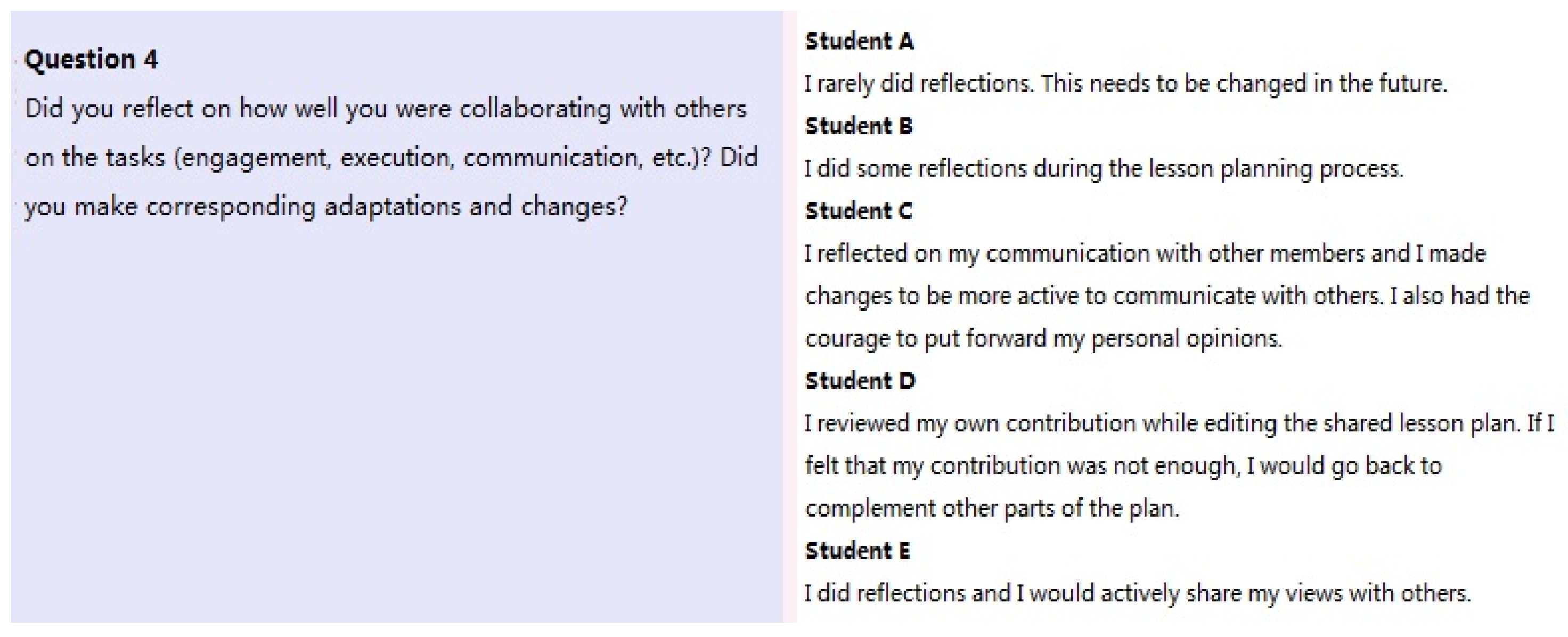

Appendix C. Reflection on the SCLP Procedure

- What challenges did you face during the shared collaborative lesson planning, and how did you address them?

- Did you modify the task understanding and goal setting during the initial stage of the shared collaborative lesson planning? How did you make adaptations?

- Were there any disagreements when collaborating with group members? How did you handle these conflicts?

- Did you reflect on your performance in the shared collaborative lesson planning (e.g., your participation, task implementation, communication with other members)? Did you make any adaptations?

- Was the participation in task discussion and collaboration evenly distributed among all group members?

- Do you believe it is necessary to apply and integrate CSCL tools into the lesson plans and simulated teaching? Do these tools facilitate or hinder the shared collaborative lesson planning activities?

- Please provide a comprehensive evaluation of your performance. What areas do you believe need improvement for future collaborative lesson planning activities?

References

- Alloway, M. (2014). Collaborative lesson planning as a form of professional development? A study of learning opportunities presented through collaborative planning [Doctoral dissertation, University of Washington]. [Google Scholar]

- Backfisch, I., Franke, U., Ohla, K., Scholtz, N., & Lachner, A. (2023). Collaborative design practices in pre-service teacher education for technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): Group composition matters. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 51(4), 579–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauml, M. (2014). Collaborative lesson planning as professional development for beginning primary teachers. The New Educator, 10(3), 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajkler, W., Wood, P., Norton, J., & Pedder, D. (2014). Lesson study as a vehicle for collaborative teacher learning in a secondary school. Professional Development in Education, 40(4), 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A., Hamilton, S., Gervasoni, A., Cram, K., & Cullen, R. (2023). An approach to facilitating collaborative planning in mathematics. Australian Primary Mathematics Classroom, 28(1), 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dignath, C., & Veenman, M. V. J. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning—Evidence from classroom observation studies. Educational Psychology Review, 33(2), 489–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnsworth, V., Kleanthous, I., & Wenger-Trayner, E. (2016). Communities of practice as a social theory of learning: A conversation with Etienne Wenger. British Journal of Educational Studies, 64(2), 139–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, T., & Beckey, A. (2023). Teaching about planning in pre-service physical education teacher education: A collaborative self-study. European Physical Education Review, 29(3), 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X., & Qian, X. (2016). Research on the teachers’ online collaborative lesson planning process in the era of Internet Plus. Chinese Journal of ICT in Education, 3, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, R., Goddard, Y., Sook Kim, E., & Miller, R. (2015). A theoretical and empirical analysis of the roles of instructional leadership, teacher collaboration, and collective efficacy beliefs in support of student learning. American Journal of Education, 121(4), 501–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, P. (2007). Improving teacher effectiveness through structured collaboration: A case study of a professional learning community. RMLE Online, 31(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierez, S. B. (2021). Collaborative lesson planning as a positive ‘dissonance’ to the teachers’ individual planning practices: Characterizing the features through reflections-on-action. Teacher Development, 25(1), 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, A. F., Järvelä, S., & Miller, M. (2017). Self-regulated, co-regulated, and socially shared regulation of learning. In D. H. Schunk, & J. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance (pp. 83–106). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Sellés, N., Muñoz-Carril, P. C., & González-Sanmamed, M. (2019). Computer-supported collaborative learning: An analysis of the relationship between interaction, emotional support and online collaborative tools. Computers & Education, 138, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L., Wang, R., & Han, J. (2024). Regulation of emotions in project-based collaborative learning: An empirical study in academic English classrooms. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1368196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurme, T. R., Merenluoto, K., & Järvelä, S. (2009). Socially shared metacognition of pre-service primary teachers in a computer-supported mathematics course and their feelings of task difficulty: A case study. Educational Research and Evaluation, 15(5), 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurme, T. R., Palonen, T., & Jrvel, S. (2006). Metacognition in joint discussion: An analysis of the patterns of interaction and the metacognitive content of the networked discussions in mathematics. Metacognition & Learning, 1(2), 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Isohätälä, J., Järvenoja, H., & Järvelä, S. (2017). Socially shared regulation of learning and participation in social interaction in collaborative learning. International Journal of Educational Research, 81, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S., & Hadwin, A. F. (2013). New frontiers: Regulating learning in CSCL. Educational psychologist, 48(1), 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S., Järvenoja, H., Malmberg, J., & Hadwin, A. F. (2013). Exploring socially shared regulation in the context of collaboration. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 12(3), 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S., Malmberg, J., & Koivuniemi, M. (2016). Recognizing socially shared regulation by using the temporal sequences of online chat and logs in CSCL. Learning and Instruction, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Järvelä, S., Nguyen, A., Vuorenmaa, E., Malmberg, J., & Järvenoja, H. (2023). Predicting regulatory activities for socially shared regulation to optimize collaborative learning. Computers in Human Behavior, 144, 107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, J., Heine, S., Jäger-Biela, D., & Rothland, M. (2024). ICT integration in teachers’ lesson plans: A scoping review of empirical studies. European Journal of Teacher Education, 47(4), 821–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkonen, J., Dillon, P., Kärkkäinen, S., Hartikainen-Ahia, A., & Keinonen, T. (2016). Pre-service teachers’ experiences of scaffolded learning in science through a computer supported collaborative inquiry. Education and Information Technologies, 21, 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A., O’Donnell, A. M., & Rogat, T. K. (2015). Exploration of the cognitive regulatory sub-processes employed by groups characterized by socially shared and other-regulation in a CSCL context. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J., & Zhao, W. (2011). Collective lesson planning: Its meaning, problems and strategies for change. Journal of Northwest Normal University (Social Science), 48(6), 73–79. [Google Scholar]

- Liou, Y. H., Daly, A. J., Canrinus, E. T., Forbes, C. A., Moolenaar, N. M., Cornelissen, F., Van Lare, M., & Hsiao, J. (2017). Mapping the social side of pre-service teachers: Connecting closeness, trust, and efficacy with performance. Teachers and Teaching, 23(6), 635–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmberg, J., Järvelä, S., Järvenoja, H., & Panadero, E. (2015). Promoting socially shared regulation of learning in CSCL: Progress of socially shared regulation among high-and low-performing groups. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 562–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiyah, R. S., & Faaizah, S. (2015). The development of online project based collaborative learning using ADDIE model. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1803–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakata, Y., Nitta, R., & Tsuda, A. (2022). Understanding motivation and classroom modes of regulation in collaborative learning: An exploratory study. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 16(1), 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näykki, P., Järvenoja, H., Järvelä, S., & Kirschner, P. (2017). Monitoring makes a difference: Quality and temporal variation in teacher education students’ collaborative learning. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 61(1), 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, O., Weinberger, A., Biemans, H. J., Mulder, M., & Chizari, M. (2013). Facilitating argumentative knowledge construction through a transactive discussion script in CSCL. Computers & Education, 61, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ortube, A. F., Panadero, E., & Dignath, C. (2024). Self-regulated learning interventions for pre-service teachers: A systematic review. Educational Psychology Review, 36(4), 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E., & Järvelä, S. (2015). Socially shared regulation of learning: A review. European Psychologist, 20(3), 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H. T. T., Le, N. M. T., Doan, H. T. T., & Luong, H. T. (2023). Examining philology teachers’ lesson planning competencies in Vietnam. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 22(6), 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. S. (2019). Teachers’ peer support: Difference between perception and practice. Teacher Development, 23(1), 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakıcıoğlu-Söylemez, A., Ölçü-Dinçer, Z., Balıkçı, G., Taner, G., & Akayoğlu, S. (2018). Professional learning with and from peers: Pre-service EFL teachers’ reflections on collaborative lesson-planning. Abant İzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi, 18(1), 392–415. [Google Scholar]

- Ruys, I., Keer, H., & Aelterman, A. (2012). Examining pre-service teacher competence in lesson planning pertaining to collaborative learning. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 44(3), 349–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, R., Rietz, F., & Kreis, A. (2018). What are the effects of science lesson planning in peers?—Analysis of attitudes and knowledge based on an actor-partner interdependence model. Research in Science Education, 48(3), 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulla, F., Monacis, D., & Limone, P. (2023). A systematic review of the role of teachers’ support in promoting socially shared regulatory strategies for learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1208012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thobela, N. M., Sekao, R. D., & Ogbonnaya, U. I. (2023). Mathematics teachers’ use of textbooks for instructional decision-making in lesson study. Journal of Pedagogical Research, 7(4), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Tondeur, J., Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., & Baran, E. (2020). Enhancing pre-service teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK): A mixed-method study. Educational Technology Research & Development, 68(1), 319–343. [Google Scholar]

- Ucan, S., & Webb, M. (2015). Social regulation of learning during collaborative inquiry learning in science: How does it emerge and what are its functions? International Journal of Science Education, 37(15), 2503–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, F., Kollar, I., Fischer, F., Reiss, K., & Ufer, S. (2022). Adaptable scaffolding of mathematical argumentation skills: The role of self-regulation when scaffolded with CSCL scripts and heuristic worked examples. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 17(1), 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, J., Laferriere, T., Breuleux, A., Itow, R. C., Hickey, D. T., & McKenney, S. (2015). Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instructional Science, 43, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R. A., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Widjaja, W., Groves, S., & Ersozlu, Z. (2021). Designing and delivering an online lesson study unit in mathematics to pre-service primary teachers: Opportunities and challenges. International Journal for Lesson & Learning Studies, 10(2), 230–242. [Google Scholar]

- Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated learning. In D. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. Graesser (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice (pp. 277–304). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, R., & Zhang, J. (2016). Promoting teacher collaboration through joint lesson planning: Challenges and coping strategies. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Chen, J., Wen, Y., Chen, H., Gao, Q., & Wang, Q. (2021). Capturing regulatory patterns in online collaborative learning: A network analytic approach. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 16(1), 37–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J., Xing, W., & Zhu, G. (2019). Examining sequential patterns of self-and socially shared regulation of STEM learning in a CSCL environment. Computers & Education, 136, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L., Cui, P., & Zhang, X. (2020). Does collaborative learning design align with enactment? an innovative method of evaluating the alignment in the CSCL context. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 15(3), 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L., Long, M., Niu, J., & Zhong, L. (2023). An automated group learning engagement analysis and feedback approach to promoting collaborative knowledge building, group performance, and socially shared regulation in CSCL. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 18(1), 101–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., Shang, C., Xu, W., Zhang, P., Zhao, Y., & Liu, Y. (2024). Investigating the role of socially shared regulation of learning in fostering student teachers’ online collaborative reflection abilities. Education and Information Technologies, 30, 8805–8827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J., & Schunk, D. H. (2011). Self-regulated learning and performance: An introduction and an overview. In D. H. Schunk, & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 15–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Questions | Member 1 | Member 2 | Member 3 | Member 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Dimension | ||||

| During the shared collaborative lesson planning activities, who did you share your knowledge and skills with? | * | * | * | * |

| Who evaluated your work or provided suggestions to you when finishing the task? | * | * | * | * |

| Who did you talk to when you have difficulty during the activities? | * | * | * | * |

| Whose suggestions are useful during the activities? | * | * | * | |

| Metacognitive Dimension (Stage) | ||||

| During the shared collaborative lesson planning activities, who did you discuss with on the task requirements? (task understanding) | * | * | * | * |

| Who did you work with to construct the task schedule? (planning) | * | * | * | * |

| Who did you discuss with to set up the task assignments? (task assignment) | * | * | * | * |

| Who did you discuss or share with about information of the progress of group works? (monitoring) | * | * | * | * |

| Who did you discuss with to resolve problems emerged in the process of shared collaborative lesson planning? (adaptation) | * | * | * | * |

| After the shared collaborative lesson planning activities, who did you work with to do the reflection? (reflection) | * | * | ||

| Motivational/Emotional Dimension | ||||

| During the shared collaborative lesson planning, whose ideas or works did you appreciate? | * | * | ||

| Who ignored your ideas or suggestions? | ||||

| Who opposed or reluctant to support your ideas or works? | * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guo, C.; Chen, X.; Chen, J. Enhancing Prospective Teachers’ Professional Development Through Shared Collaborative Lesson Planning. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060753

Guo C, Chen X, Chen J. Enhancing Prospective Teachers’ Professional Development Through Shared Collaborative Lesson Planning. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):753. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060753

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Chen, Xiangdong Chen, and Jiawen Chen. 2025. "Enhancing Prospective Teachers’ Professional Development Through Shared Collaborative Lesson Planning" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060753

APA StyleGuo, C., Chen, X., & Chen, J. (2025). Enhancing Prospective Teachers’ Professional Development Through Shared Collaborative Lesson Planning. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060753