Crafting Careers: Unraveling the Impact of Career Crafting on Career Outcomes and the Moderating Role of Supervisor Career Support Mentoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

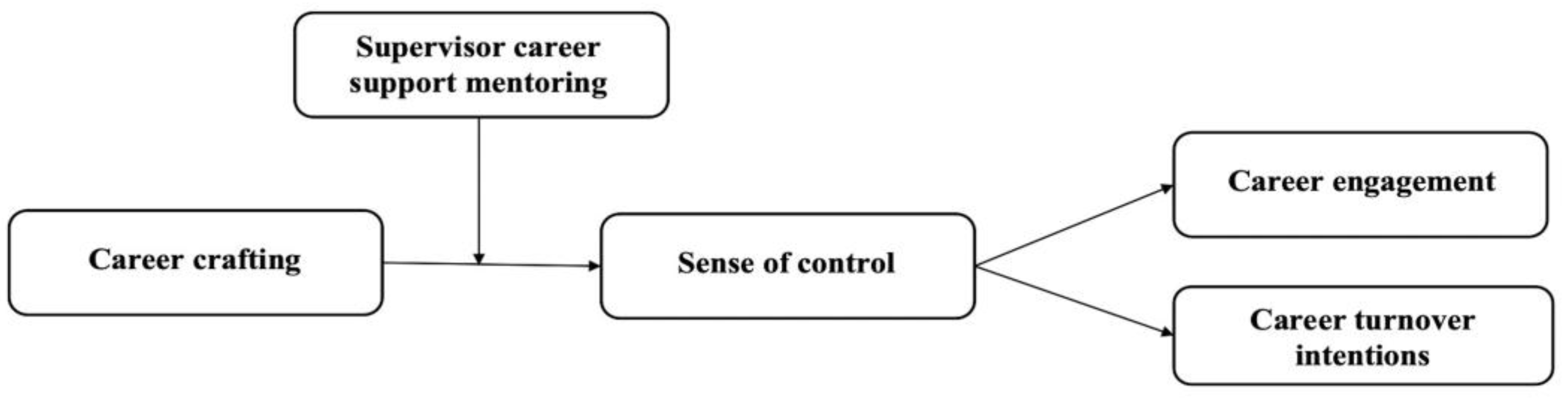

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Career Crafting, Conservation of Resources Theory, and Career Construction Theory

2.2. Career Crafting and Career Outcomes

2.3. The Moderating Role of Supervisor Career Support Mentoring

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Procedure

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Career Crafting (T1)

3.2.2. Supervisor Career Support Mentoring (T1)

3.2.3. Sense of Control (T2)

3.2.4. Career Engagement (T3)

3.2.5. Career Turnover Intentions (T3)

3.2.6. Control Variables

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses

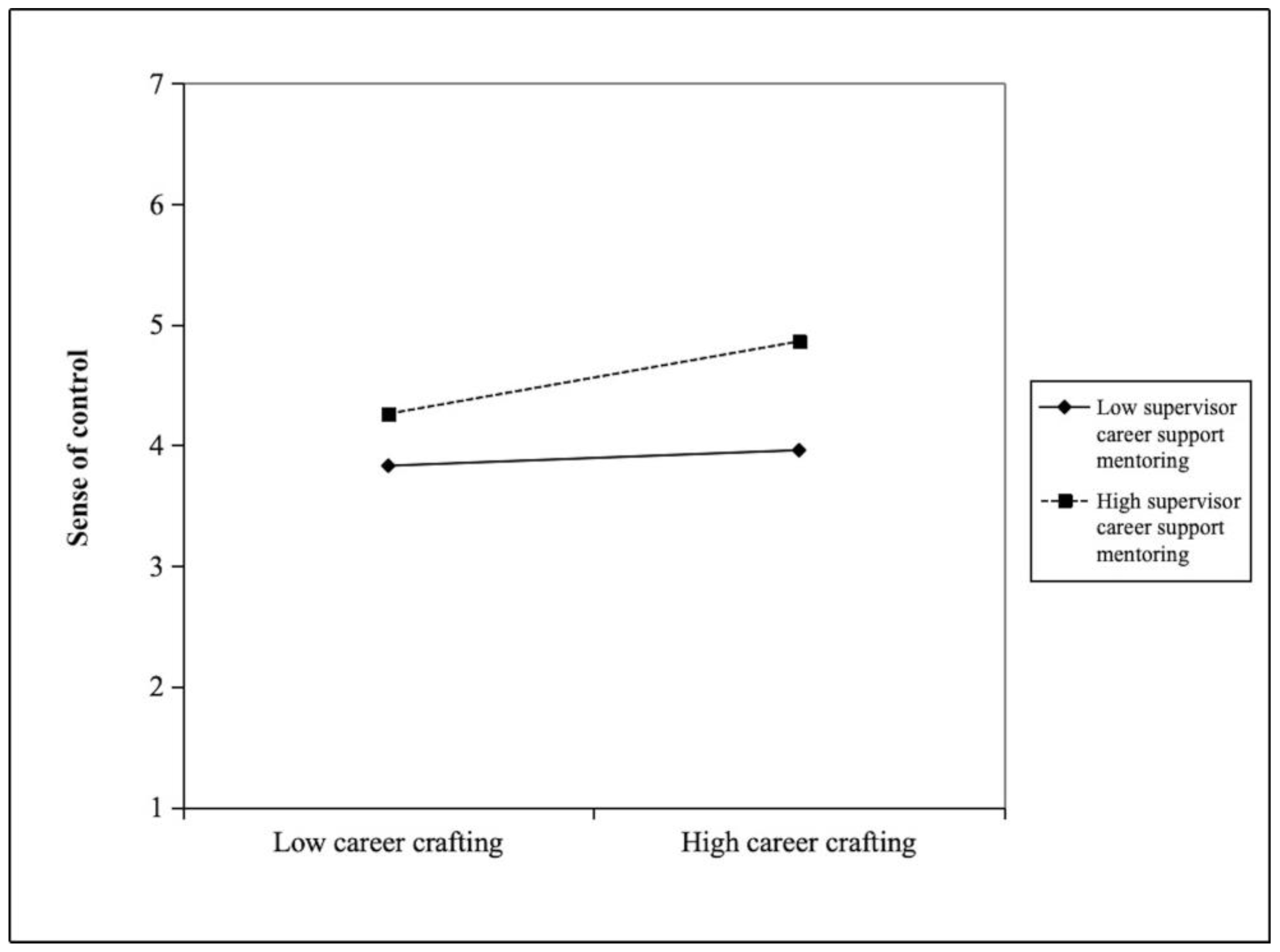

4.2. Hypothesis Testing

5. General Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akkermans, J., & Hirschi, A. (2023). Career proactivity: Conceptual and theoretical reflections. Applied Psychology, 72(1), 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkermans, J., & Tims, M. (2017). Crafting your career: How career competencies relate to career success via job crafting. Applied Psychology, 66(1), 168–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarifi, A., Bajaba, S., & Basahal, A. (2024). From self-commitment to career crafting: The mediating role of career adaptability and the moderating role of job autonomy. Acta Psychologica, 248, 104387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baillod, J., & Semmer, N. (1994). Fluktuation und berufsverläufe bei computerfachleuten. Zeitschrift für Arbeits-und Organisationspsychologie, 38, 152–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bankins, S., Ocampo, A. C., Marrone, M., Restubog, S. L. D., & Woo, S. E. (2024). A multilevel review of artificial intelligence in organizations: Implications for organizational behavior research and practice. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(2), 159–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthauer, L., Kaucher, P., Spurk, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Burnout and career (un)sustainability: Looking into the Blackbox of burnout triggered career turnover intentions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2016). A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 229–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breevaart, K., & Tims, M. (2019). Crafting social resources on days when you are emotionally exhausted: The role of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(4), 806–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In Handbook of cross-cultural psychology: Methodology (pp. 389–444). Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Bufquin, D., Park, J. Y., Back, R. M., de Souza Meira, J. V., & Hight, S. K. (2021). Employee work status, mental health, substance use, and career turnover intentions: An examination of restaurant employees during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z., Ji, X., & Wang, Z. (2024). Career Insecurity Scale Short Form (CI-S): Construction and validation. Journal of Career Assessment. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P. C., Guo, Y., Cai, Q., & Guo, H. (2023). Proactive career orientation and subjective career success: A perspective of career construction theory. Behavioral Sciences, 13(6), 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S. J., Van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2020). Common method variance in international business research. In Research methods in international business (pp. 385–398). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J. C., & Yi, O. (2018). Hotel employee job crafting, burnout, and satisfaction: The moderating role of perceived organizational support. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 72, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H., Guan, Y., Zhou, X., Li, Y., Cai, D., Li, N., & Liu, B. (2023). The “double-edged sword” effects of career support mentoring on newcomer turnover: How and when it helps or hurts. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(7), 1094–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A., Akkermans, J., & Van der Heijden, B. (2019). From occupational choice to career crafting. In The Routledge companion to career studies (pp. 128–142). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, A., Van der Heijden, B. I., & Akkermans, J. (2020). Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 117, 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaa, N. M., Abidin, A. Z. U., & Roller, M. (2024). Examining the relationship of career crafting, perceived employability, and subjective career success: The moderating role of job autonomy. Future Business Journal, 10(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doden, W., Bindl, U., & Unger, D. (2024). Does it take two to tango? Combined effects of relational job crafting and job design on energy and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 45(8), 1189–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durbin, J., & Watson, G. S. (1950). Testing for serial correlation in least squares regression: I. Biometrika, 37(3/4), 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elst, T. V., De Cuyper, N., & De Witte, H. (2011). The role of perceived control in the relationship between job insecurity and psychosocial outcomes: Moderator or mediator? Stress and Health, 27(3), e215–e227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, B., Kudret, S., Campion, E. D., Bauer, T. N., McCarthy, J., & Cheng, B. H. (2025). Under pressure: Employee work stress, supervisory mentoring support, and employee career success. Personnel Psychology, 78(1), 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, E., Boon, C., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2021). The moderating role of HR practices on the career adaptability–job crafting relationship: A study among employee–manager dyads. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(6), 1339–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A. S., Erickson, R. J., Diefendorff, J. M., & Krantz, D. (2020). When does feeling in control benefit well-being? The boundary conditions of identity commitment and self-esteem. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Zhao, C., Cooke, F. L., Zhang, B., & Xie, R. (2020). Only time can tell: Whether and when the improvement in career development opportunities alleviates knowledge workers’ emotional exhaustion in the Chinese context. British Journal of Management, 31(1), 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X., Gao, L., & Yu, H. (2023). A new construct in career research: Career crafting. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tatham, R., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis with readings. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J. R., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR” understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, L. K., Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2016). Can job crafting reduce job boredom and increase work engagement? A three-year cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 95, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harju, L. K., Kaltiainen, J., & Hakanen, J. J. (2021). The double-edged sword of job crafting: The effects of job crafting on changes in job demands and employee well-being. Human Resource Management, 60(6), 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, L., Yang, W., Miao, J., & Chen, J. (2024). The impact of supervisory career support on employees’ well-being: A dual path model of opportunity and ability. International Journal of Mental Health Promotion, 26(11), 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., & Freund, P. A. (2014). Career engagement: Investigating intraindividual predictors of weekly fluctuations in proactive career behaviors. The Career Development Quarterly, 62(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., Freund, P. A., & Herrmann, A. (2014). The career engagement scale: Development and validation of a measure of proactive career behaviors. Journal of Career Assessment, 22(4), 575–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., & Koen, J. (2021). Contemporary career orientations and career self-management: A review and integration. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 126, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschi, A., Nagy, N., Baumeler, F., Johnston, C. S., & Spurk, D. (2018). Assessing key predictors of career success: Development and validation of the career resources questionnaire. Journal of Career Assessment, 26(2), 338–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, D., Escaffi-Schwarz, M., Vasquez, C. A., Irmer, J. P., & Zapf, D. (2024). Does job crafting affect employee outcomes via job characteristics? A meta-analytic test of a key job crafting mechanism. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 97(1), 47–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infurna, F. J., Gerstorf, D., Ram, N., Schupp, J., Wagner, G. G., & Heckhausen, J. (2016). Maintaining perceived control with unemployment facilitates future adjustment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 93, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, E., van der Heijden, B. I., Akkermans, J., & Audenaert, M. (2021). Unraveling the complex relationship between career success and career crafting: Exploring nonlinearity and the moderating role of learning value of the job. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 130, 103620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, E., & Kitapci, H. (2024). Contextual and individual determinants of sustainable careers: A serial indirect effect model through career crafting and person-career fit. Sustainability, 16(7), 2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunce, J. T., Cook, D. W., & Miller, D. E. (1975). Random variables and correlational overkill. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 35(3), 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Y., Chen, C. L., Kolokowsky, E., Hong, S., Siegel, J. T., & Donaldson, S. I. (2021). Development and validation of the career crafting assessment (CCA). Journal of Career Assessment, 29(4), 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P. C., Xu, S. T., & Yang, W. (2021). Is career adaptability a double-edged sword? The impact of work social support and career adaptability on turnover intentions during the COVID–19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, A. M. W., Bai, J. Y., Luo, J. M., & Fan, D. X. (2024). Why do negative career shocks foster perceived employability and career performance: A career crafting explanation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 119, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A., Shaffer, J. A., Wang, Z., & Huang, J. L. (2021). Work-family conflict, perceived control, and health, family, and wealth: A 20-year study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 127, 103562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Huang, S., & Feng, Z. (2024). The complexity of Machiavellian leaders: How and when leader Machiavellianism impacts abusive supervision. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Qin, X., Yam, K. C., Deng, H., Chen, C., Dong, X., Jiang, L., & Tang, W. (2024a). Embracing artificial intelligence (AI) with job crafting: Exploring trickle-down effect and employees’ outcomes. Tourism Management, 104, 104935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W., Xu, Y., Jiang, T., & Cheung, C. (2024b). The effects of over-service on restaurant consumers’ satisfaction and revisit intention. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 122, 103881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Zhang, Y., Yan, D., Wen, F., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Nurses’ intention to stay: The impact of perceived organizational support, job control and job satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(5), 1141–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu-Lastres, B., Huang, W. J., & Bao, H. (2023). Exploring hospitality workers’ career choices in the wake of COVID-19: Insights from a phenomenological inquiry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 111, 103485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W., Liu, S., Wu, H., Wu, K., & Pei, J. (2022). To avoidance or approach: Unraveling hospitality employees’ job crafting behavior response to daily customer mistreatment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 53, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luksyte, A., & Carpini, J. A. (2024). Perceived overqualification and subjective career success: Is harmonious or obsessive passion beneficial? Applied Psychology, 73(4), 2077–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., & Hocevar, D. (1988). A new, more powerful approach to multitrait-multimethod analyses: Application of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 73(1), 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijerink, J., Bos-Nehles, A., & de Leede, J. (2020). How employees’ pro-activity translates high-commitment HRM systems into work engagement: The mediating role of job crafting. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(22), 2893–2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, J. N., Quintane, E., Hirst, G., & Carnegie, A. (2022). Protecting their turf: When and why supervisors undermine employee boundary spanning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(6), 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, X., Zhu, X., Bian, W., Li, J., Pan, C., & Pan, C. (2024). How does leader career calling stimulate employee career growth? The role of career crafting and supervisor-subordinate guanxi. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 45(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilforooshan, P., & Salimi, S. (2016). Career adaptability as a mediator between personality and career engagement. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 94, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’brien, G. E. (1983). Skill-utilization, skill-variety and the job characteristics model. Australian Journal of Psychology, 35(3), 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A. C. G., Restubog, S. L. D., Liwag, M. E., Wang, L., & Petelczyc, C. (2018). My spouse is my strength: Interactive effects of perceived organizational and spousal support in predicting career adaptability and career outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 108, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I. J., Kim, P. B., Hai, S., & Dong, L. (2020). Relax from job, don’t feel stress! The detrimental effects of job stress and buffering effects of coworker trust on burnout and turnover intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 559–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S., & Park, S. (2023). Contextual antecedents of job crafting: Review and future research agenda. European Journal of Training and Development, 47(1/2), 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., Podsakoff, N. P., Williams, L. J., Huang, C., & Yang, J. (2024). Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 11(1), 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaprasad, B. S., Rao, S., Rao, N., Prabhu, D., & Kumar, M. S. (2022). Linking hospitality and tourism students’ internship satisfaction to career decision self-efficacy: A moderated-mediation analysis involving career development constructs. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 30, 100348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). Toward a comprehensive theory of career development: Dispositions, concerns, and narratives. In Contemporary models in vocational psychology (pp. 303–328). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. In Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (Vol. 2, pp. 144–180). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, S. E., Nielsen, J. D., & Kraimer, M. L. (2021). Awakening the entrepreneur within: Entrepreneurial identity aspiration and the role of displacing work events. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(8), 1224–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., She, Z., Zhou, Z. E., Zhang, N., & Zhang, H. (2022). Job crafting and employee life satisfaction: A resource-gain-development perspective. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 14(4), 1483–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibiti, R. (2020). Public school teachers’ satisfaction with retention factors in relation to work engagement. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 46(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirola, N. (2024). Job insecurity and well-being: Integrating life history and transactional stress theories. Academy of Management Journal, 67(3), 679–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steindórsdóttir, B. D., Sanders, K., Nordmo, M., & Dysvik, A. (2024). A cross-lagged study investigating the relationship between burnout and subjective career success from a lifespan developmental perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 97(1), 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarjo, R. A., Supratikno, H., Sudibjo, N., Bernarto, I., & Pramono, R. (2021). The mediating role of dynamic career adaptability in the effect of perceived organizational support and perceived supervisor support on work engagement of millennials. International Journal of Entrepreneurship, 25, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G., Chen, Y., van Knippenberg, D., & Yu, B. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of empowering leadership: Leader power distance, leader perception of team capability, and team innovation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(6), 551–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavitiyaman, P., Tsui, B., & Ng, P. M. L. (2025). Effect of hospitality and tourism students’ perceived skills on career adaptability and perceived employability. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 37(1), 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M., & Akkermans, J. (2020). Job and career crafting to fulfill individual career pathways. In Career pathways-school to retirement and beyond (pp. 165–190). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). Development and validation of the job crafting scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tims, M., Derks, D., & Bakker, A. B. (2016). Job crafting and its relationships with person–job fit and meaningfulness: A three-wave study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2015). Development of early vocational behavior: Parallel associations between career engagement and satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Elst, T., Richter, A., Sverke, M., Näswall, K., De Cuyper, N., & De Witte, H. (2014). Threat of losing valued job features: The role of perceived control in mediating the effect of qualitative job insecurity on job strain and psychological withdrawal. Work & Stress, 28(2), 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Owens, B. P., Li, J. J., & Shi, L. (2018). Exploring the affective impact, boundary conditions, and antecedents of leader humility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(9), 1019–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T., Zhang, Y., Wang, J., Miao, H., & Guo, C. (2024). Career decision self-efficacy mediates social support and career adaptability and stage differences. Journal of Career Assessment, 32(2), 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Zheng, Y., Wu, C. H., Wu, W., & Xia, Y. (2024). Why and when newcomer career consultation behaviour attracts career mentoring from supervisors: A sociometer explanation of supervisors’ perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 97(2), 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, K., Kira, M., & Klehe, U. C. (2019). Putting career construction into context: Career adaptability among refugees. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 111, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woehler, M., Floyd, T. M., Shah, N., Marineau, J. E., Sung, W., Grosser, T. J., Fagan, J., & Labianca, G. J. (2021). Turnover during a corporate merger: How workplace network change influences staying. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(12), 1939–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. M., Cropanzano, R., McWha-Hermann, I., & Lu, C. Q. (2024). Multiple salary comparisons, distributive justice, and employee withdrawal. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(10), 1533–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yam, K. C., Christian, M. S., Wei, W., Liao, Z., & Nai, J. (2018). The mixed blessing of leader sense of humor: Examining costs and benefits. Academy of Management Journal, 61(1), 348–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Yan, X., Zhao, X. R., Mattila, A. S., Cui, Z., & Liu, Z. (2022). A two-wave longitudinal study on the impacts of job crafting and psychological resilience on emotional labor. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H. (2015). Daily manifestations of career adaptability: Relationships with job and career outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacher, H. (2016). Within-person relationships between daily individual and job characteristics and daily manifestations of career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 92, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Five-factor model | 124.89 | 80 | 1.56 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| 2. Four-factor model: | 201.37 | 84 | 2.40 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| CC + SOC | |||||||

| 3. Three-factor model: | 401.94 | 87 | 4.62 | 0.82 | 0.78 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| CC + SOC + SCSM | |||||||

| 4. Two-factor model: | 618.19 | 89 | 6.95 | 0.70 | 0.65 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| CC + SOC + SCSM + CTI | |||||||

| 5. One-factor model: | 761.97 | 90 | 8.47 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.11 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Career crafting (T1) | 4.95 | 0.83 | 0.82 | ||||

| 2. Supervisor career support mentoring (T1) | 5.08 | 1.09 | 0.44 ** | 0.90 | |||

| 3. Sense of control (T2) | 5.15 | 0.75 | 0.35 ** | 0.46 ** | 0.83 | ||

| 4. Career engagement (T3) | 5.78 | 0.56 | 0.36 ** | 0.45 ** | 0.41 ** | 0.81 | |

| 5. Career turnover intentions (T3) | 2.93 | 1.25 | −0.23 ** | −0.46 ** | −0.36 ** | −0.49 ** | 0.83 |

| Direct Effect | B | SE |

| Career crafting → Sense of control | 0.33 *** | 0.05 |

| Sense of control → Career engagement | 0.25 *** | 0.05 |

| Sense of control → Career turnover intentions | −0.52 *** | 0.11 |

| Career crafting → Career engagement | 0.16 *** | 0.04 |

| Career crafting → Career turnover intentions | −0.18 | 0.10 |

| Indirect Effect | Estimate | 95% CI |

| Career crafting → Sense of control → Career engagement | 0.08 | [0.045, 0.139] |

| Career crafting → Sense of control → Career turnover intentions | −0.17 | [−0.274, −0.094] |

| Variables | Sense of Control | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Constant | 4.11 *** (0.49) | 4.27 *** (0.42) | 4.23 *** (0.41) |

| Controls | |||

| Age | −0.24 * (0.10) | −0.32 *** (0.09) | −0.33 *** (0.09) |

| Gender | 0.04 * (0.02) | 0.03 * (0.02) | 0.03 * (0.02) |

| Education | 0.03 (0.10) | 0.10 (0.09) | 0.10 (0.08) |

| Job tenure | −0.04 (0.02) | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Predictor | |||

| Career crafting (A) | 0.17 ** (0.06) | 0.22 *** (0.06) | |

| Supervisor career support mentoring (B) | 0.27 *** (0.04) | 0.31 *** (0.04) | |

| A × B | 0.13 ** (0.04) | ||

| R2 | 0.05 | 0.30 *** | 0.34 ** |

| ΔR2 | 0.25 | 0.04 | |

| F value | 2.84 | 16.15 *** | 16.26 *** |

| Moderator | Level | Outcome Variables | Indirect Effect | Boot SE | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supervisor career support mentoring | Low | Career engagement | 0.01 | 0.02 | [−0.008, 0.058] |

| Medium | 0.04 | 0.02 | [0.011, 0.089] | ||

| High | 0.06 | 0.03 | [0.021, 0.137] | ||

| Dif | 0.05 | 0.03 | [0.008, 0.110] | ||

| Low | Career turnover intentions | −0.02 | 0.03 | [−0.091, 0.018] | |

| Medium | −0.06 | 0.03 | [−0.143, −0.009] | ||

| High | −0.10 | 0.05 | [−0.226, −0.013] | ||

| Dif | −0.08 | 0.05 | [−0.207, −0.002] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fu, A.; Wang, S.; Gan, X.; Hai, S. Crafting Careers: Unraveling the Impact of Career Crafting on Career Outcomes and the Moderating Role of Supervisor Career Support Mentoring. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060740

Fu A, Wang S, Gan X, Hai S. Crafting Careers: Unraveling the Impact of Career Crafting on Career Outcomes and the Moderating Role of Supervisor Career Support Mentoring. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):740. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060740

Chicago/Turabian StyleFu, Anguo, Shuaihua Wang, Xinyao Gan, and Shenyang Hai. 2025. "Crafting Careers: Unraveling the Impact of Career Crafting on Career Outcomes and the Moderating Role of Supervisor Career Support Mentoring" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060740

APA StyleFu, A., Wang, S., Gan, X., & Hai, S. (2025). Crafting Careers: Unraveling the Impact of Career Crafting on Career Outcomes and the Moderating Role of Supervisor Career Support Mentoring. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 740. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060740