Burnout, Work Addiction and Stress-Related Growth Among Emergency Physicians and Residents: A Comparative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

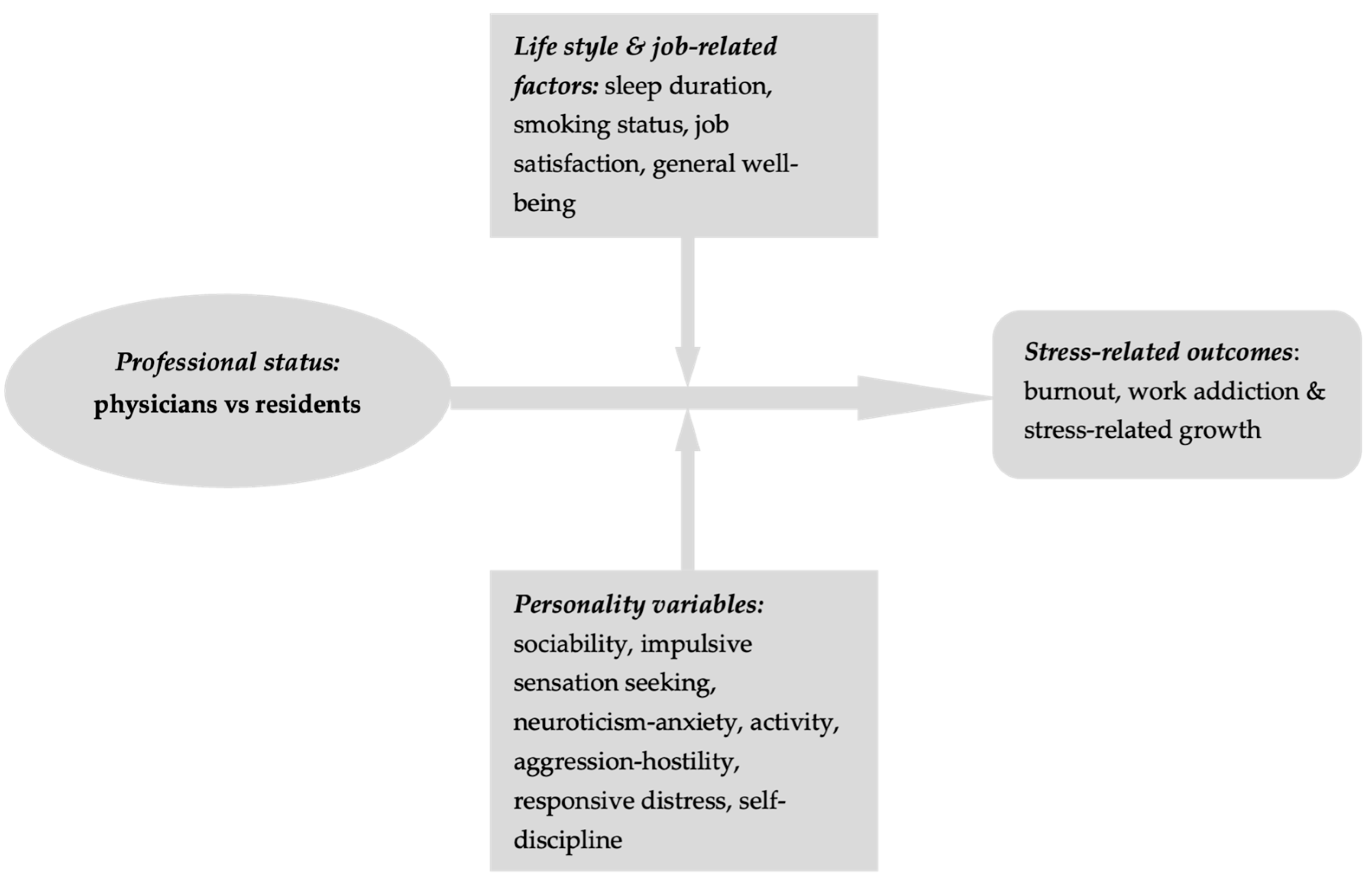

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Measures

2.3. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alanazy, A. R. M., & Alruwaili, A. (2023). The global prevalence and associated factors of burnout among emergency department healthcare workers and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare, 11(15), 2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcon, G., Eschleman, K. J., & Bowling, N. A. (2009). Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work Stress, 23(3), 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salamah, T. A., Farook, F. F., Al-Kanhal, A. A., Almutairi, A., Al-Ghofili, M., & Banaeem, A. R. (2024). Factors associated with psychological distress in emergency medicine residents: Findings from a single-center study. Signa Vitae, 20(5), 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, G. (2023). Big five model personality traits and job burnout: A systematic literature review. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arora, M., Asha, S., Chinnappa, J., & Diwan, A. D. (2013). Review article: Burnout in emergency medicine physicians. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 25(6), 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, W. F., & Mathias, L. A. d. S. T. (2017). Work addiction and quality of life: A study with physicians. Einstein (Sao Paulo), 15(2), 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Baier, N., Roth, K., Felgner, S., & Henschke, C. (2018). Burnout and safety outcomes—A cross-sectional nationwide survey of EMS-workers in Germany. BMC Emergency Medicine, 18(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Barchard, K. A. (2001). The levels of emotional awareness scale and emotional expressivity [Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, University of British Columbia]. Available online: https://img.faculty.unlv.edu/lab/conference-presentations/conference%20posters/LEASandEEWPA2001.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Bi, X., Proulx, J., & Aldwin, C. M. (2006). Stress-related growth. In H. Friedman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mental health (2nd ed.). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, R. (2018). Burnout is more strongly linked to neuroticism than to work-contextualized factors. Psychiatry Resources, 270, 901–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutou, A., Pitsiou, G., Sourla, E., & Kioumis, I. (2019). Burnout syndrome among emergency medicine physicians: An update on its prevalence and risk factors. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 23(20), 9058–9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S., Amlôt, R., Rubin, G. J., & Greenberg, N. (2020). Psychological resilience and post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organisations: Overview of the literature. BMJ Military Health, 166(1), 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burke, R. J., Matthiesen, S. B., & Pallesen, S. (2006). Personality correlates of workaholism. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(6), 1223–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butoi, M. A., Vancu, G., Marcu, R.-C., Hermenean, A., Puticiu, M., & Rotaru, L. T. (2025). The role of personality in explaining burnout, work addiction, and stress-related growth in prehospital emergency personnel. Healthcare, 13, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J., Ray, J. M., Joseph, D., Evans, L. V., & Joseph, M. (2022). Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms among emergency medicine resident physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 23(2), 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Del Líbano, M., Llorens, S., Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Validity of a brief workaholism scale. Psicothema, 22(1), 143–150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, D. J., He, C., Leslie, Q., Clark, M. A., & Lewiss, R. E. (2022). The emergency medicine resident retreat: Creating and sustaining a transformative and reflective experience. Cureus, 14(8), e27601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Griffiths, M. D. (2023). Work addiction and quality of care in healthcare: Working long hours should not be confused with addiction to work. BMJ Quality & Safety, 33, 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, M. D., Demetrovics, Z., & Atroszko, P. A. (2018). Ten myths about work addiction. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7(4), 845–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Iliescu, D., Popa, M., & Dimache, R. (2015). Adaptarea romaneasca a setului international de itemi de personalitate: IPIP-ro. Psihologia Resurselor Umane, 13, 83–112. Available online: https://www.hrp-journal.com/index.php/pru/article/download/148/152/ (accessed on 22 March 2025).

- Jackson, S. S., Fung, M.-C., Moore, M.-A. C., & Jackson, C. J. (2016). Personality and workaholism. Personality and Individual Differences, 95, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kase, J., & Doolittle, B. (2023). Job and life satisfaction among emergency physicians: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE, 18(2), e0279425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızıloğlu, M., Kircaburun, K., Özsoy, E., & Griffiths, M. (2022). Work addiction and its relation with dark personality traits: A cross-sectional study with private sector employees. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 22, 2056–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, G., Goldberg, R., & Compton, S. (2009). Tolerance for uncertainty, burnout, and satisfaction with the career of emergency medicine. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 54(1), 106–113.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kun, B., Takacs, Z. K., Richman, M. J., Griffiths, M. D., & Demetrovics, Z. (2020). Work addiction and personality: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 9(4), 945–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyron, M. J., Rees, C. S., Lawrence, D., Carleton, R. N., & McEvoy, P. M. (2021). Prospective risk and protective factors for psychopathology and wellbeing in civilian emergency services personnel: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecic-Tosevski, D., Vukovic, O., & Stepanovic, J. (2011). Stress and personality. Psychiatriki, 22(4), 290–297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, M., Battaglioli, N., Melamed, M., Mott, S. E., Chung, A. S., & Robinson, D. W. (2019). High prevalence of burnout among US emergency medicine residents: Results from the 2017 national emergency medicine wellness survey. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 74(5), 682–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K., Patey, C., Norman, P., Broens Moellekaer, A., Lim, R., Alvarez, A., & Heymann, E. P. (2024). Interventions to reduce burnout in emergency medicine: A national inventory of the Canadian experience to support global implementation of wellness initiatives. Internal and Emergency Medicine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., Van Aarsen, K., Sedran, R., & Lim, R. (2020). A national survey of burnout amongst Canadian royal college of physicians and surgeons of Canada emergency medicine residents. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 11(5), 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lu, D. W., Zhan, T., Bilimoria, K. Y., Reisdorff, E. J., Barton, M. A., Nelson, L. S., Beeson, M. S., & Lall, M. D. (2023). Workplace mistreatment, career choice regret, and burnout in emergency medicine residency training in the United States. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 81(6), 706–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manole, E. C., & Curșeu, P. L. (2024). Stress-related growth in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a panel study. Personality and Individual Differences, 222, 112578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McManus, I. C., Keeling, A., & Paice, E. (2004). Stress, burnout and doctors’ attitudes to work are determined by personality and learning style: A twelve year longitudinal study of UK medical graduates. BMC Medicine, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Merchaoui, I., Gana, A., Machghoul, S., Rassas, I., Hayouni, M. M., Bouhoula, M., Chaari, N., Hanchi, A., Amri, C., & Akrout, M. (2021). Risk of work addiction in academic physicians prevalence, determinants and impact on quality of life. International Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 5, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miclea, M., Porumb, M., Cotârlea, P., & Albu, M. (2009). Personalitate si interese. In CAS++ cognitrom assesment system (Vol. 3). ASCR. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, J. (2005). General and generalised linear models. In J. Miles, & P. Gilbert (Eds.), A handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ord, A. S., Stranahan, K. R., Hurley, R. A., & Taber, K. H. (2020). Stress-related growth: Building a more resilient brain. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clininical Neuroscience, 32(4), 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panari, C., Caricati, L., Pelosi, A., & Rossi, C. (2019). Emotional exhaustion among healthcare professionals: The effects of role ambiguity, work engagement and professional commitment. Acta Biomedica, 90(96), 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, C. L. (1998). Stress-related growth and thriving through coping: The roles of personality and cognitive processes. Journal of Social Issues, 54(2), 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C. L., Cohen, L. H., & Murch, R. L. (1996). Assessment and prediction of stress-related growth. Journal of Personality, 64(1), 71–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popa, F., Raed, A., Purcarea, V. L., Lală, A., & Bobirnac, G. (2010). Occupational burnout levels in emergency medicine—A nationwide study and analysis. Journal of Medicine and Life, 3(3), 207–215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Puticiu, M., Grecu, M.-B., Rotaru, L. T., Butoi, M. A., Vancu, G., Corlade-Andrei, M., Cimpoesu, D., Tat, R. M., & Golea, A. (2024). Exploring burnout, work addiction, and stress-related growth among prehospital emergency personnel. Behavioral Sciences, 14, 851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajvinder, S. (2018). Brief history of burnout. BMJ, 363, k5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, A., Bouju, G., Keriven-Dessomme, B., Moret, L., & Grall-Bronnec, M. (2014). Workaholism: Are physicians at risk? Occupational Medicine, 64(6), 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, J. T., Lee, J., Lu, D. W., Sundaram, V., Bird, S. B., Blomkalns, A. L., & Alvarez, A. (2022). Factors driving burnout and professional fulfillment among emergency medicine residents: A national wellness survey by the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. AEM Education and Training, 6(Suppl. 1), S5–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., van der Heijden, F. M. M. A., & Prins, J. T. (2009a). Workaholism among medical residents: It is the combination of working excessively and compulsively that counts. International Journal of Stress Management, 16(4), 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., van der Heijden, F. M. M. A., & Prins, J. T. (2009b). Workaholism, burnout and well-being among junior doctors: The mediating role of role conflict. Work & Stress, 23(2), 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W. B., Shimazu, A., & Taris, T. W. (2009c). Being driven to work excessively hard: The evaluation of a two-factor measure of workaholism in The Netherlands and Japan. Cross-Cultural Research, 43(4), 320–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., Gow, K., & Smith, S. (2005). Personality, coping and posttraumatic growth in emergency ambulance personnel. Traumatology, 11(4), 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somville, F., Van der Mleren, G., De Cauwer, H., Van Bogaert, P., & Franck, E. (2021). Burnout, stress and type D personality amongst hospital/emergency physicians. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swider, B. W., & Zimmerman, R. D. (2010). Born to burnout: A meta-analytic path model of personality, job burnout, and work outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 76(3), 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayesu, K. J., Ramoska, E. A., Clark, T. R., Hansoti, B., Dougherty, J., Freeman, W., Weaver, K. R., Chang, Y., & Gross, E. (2014). Factors associated with burnout during emergency medicine residency. Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(9), 1031–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taris, T. W., van Beek, I., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Why do perfectionists have a higher burnout risk than others? The mediational effect of workaholism. Romanian Journal of Applied Psychology, 12, 1–7. Available online: https://www.wilmarschaufeli.nl/publications/Schaufeli/334.pdf#:~:text=The%20present%20study%20proposes%20that%20workaholism%20mediates%20this,workaholics%20have%20a%20higher%20burnout%20risk%20than%20others (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ushimoto, T., Murasaka, K., Sakurai, M., Ishizaki, M., Wato, Y., Kanda, T., & Kasamaki, Y. (2023). Physicians’ resilience as a positive effect of COVID-19. Japan Medical Association Journal, 6(4), 365–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Vanyo, L. Z., Goyal, D. G., Dhaliwal, R. S., Sorge, R. M., Nelson, L. S., Beeson, M. S., Joldersma, K. B., Pai, J., & Reisdorff, E. J. (2020). Emergency medicine resident burnout and examination performance. AEM Education and Training, 5(3), e10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Verougstraete, D., & Hachimi Idrissi, S. (2020). The impact of burn-out on emergency physicians and emergency medicine residents: A systematic review. Acta Clinica Belgica, 75(1), 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, C. P., Dyrbye, L. N., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2018). Physician burnout: Contributors, consequences and solutions. Journal of Internal Medicine, 283(6), 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, K., Lank, P. M., Cheema, N., Hartman, N., & Lovell, E. O. (2018). Emergency Medicine Education Research Alliance (EMERA). Comparing the maslach burnout inventory to other well-being instruments in emergency medicine residents. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10(5), 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, W., Raj, J. P., Narayan, G., Ghiya, M., Murty, S., & Joseph, B. (2017). Quantifying burnout among emergency medicine professionals. Journal of Emergencies, Trauma and Shock, 10(4), 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Q., Mu, M. C., He, Y., Cai, Z. L., & Li, Z. C. (2020). Burnout in emergency medicine physicians: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine, 99(32), e21462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zuckerman, M. (2002). Zuckerman-kuhlman personality questionnaire (ZKPQ): An alternative five-factorial model. In B. de Raad, & M. Perugini (Eds.), Big five assessment (pp. 376–392). Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman, M., Kuhlman, D. M., Joireman, J., Teta, P., & Kraft, M. (1993). A comparison of three structural models for personality: The big three, the big five, and the alternative five. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(4), 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Physicians (N = 41) | Residents (N = 76) | Unadjusted Model p-Value | GLZ p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Men—12 (29.3%) Women—29 (70.7%) | Men—22 (28.9%) Women—54 (71.1%) | 1 1 | - |

| Age (years) | 44.61 ± 8.10 Range: 31–57 | 30.78 ± 5.79 Range: 25–50 | <0.001 2 | - |

| Smoking status | Smokers—26.8% | Smokers—44.7% | 0.074 1 | - |

| Sleep average outside working shifts (h) | 7.95 ± 1.22 Range: 4–10 | 7.00 ± 1.07 Range: 5–9 | <0.001 2 | 0.083 4 |

| Work satisfaction | 8.59 ± 0.92 Range: 5–10 | 8.79 ± 1.07 Range: 6–10 | 0.133 3 | 0.062 5 |

| General well-being | 8.37 ± 1.36 Range: 4–10 | 8.55 ± 1.43 Range: 5–10 | 0.330 3 | 0.746 5 |

| Variable | Personality Factors and Traits | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS | N-Anx | Agg-H | Act | Sy | RDS | SDS | ||

| Age | rho p | −0.507 <0.001 | −0.561 <0.001 | −0.444 <0.001 | 0.360 <0.001 | 0.446 <0.001 | −0.586 <0.001 | 0.043 0.643 |

| Sleep duration outside working shifts | rho p | −0.459 <0.001 | −0.468 <0.001 | −0.415 <0.001 | 0.386 <0.001 | 0.456 <0.001 | −0.289 0.002 | 0.241 0.009 |

| Work satisfaction | rho p | −0.139 0.135 | −0.162 0.080 | −0.153 0.099 | 0.138 0.139 | 0.145 0.119 | 0.002 0.981 | 0.106 0.254 |

| General well-being | rho p | 0.135 0.146 | 0.107 0.251 | 0.097 0.299 | −0.029 0.758 | −0.027 0.776 | 0.088 0.344 | 0.156 0.092 |

| Variable | Physicians (N = 41) | Residents (N = 76) | Unadjusted Model 1 p-Value | GLZ 2 p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociability | 13.83 ± 2.57 Range: 3–17 | 10.25 ± 4.58 Range: 2–17 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Impulsive sensation seeking | 8.41 ± 2.01 Range: 5–16 | 11.59 ± 4.29 Range: 5–18 | 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Activity | 11.39 ± 3.69 Range: 2–16 | 9.59 ± 4.67 Range: 2–16 | 0.178 | 0.528 |

| Neuroticism–anxiety | 2.95 ± 1.77 Range: 1–8 | 5.83 ± 3.74 Range: 1–11 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Aggression–hostility | 1.85 ± 1.29 Range: 1–8 | 3.16 ± 2.66 Range: 1–9 | 0.180 | 0.159 |

| Responsive distress | 4.17 ± 1.84 Range: 3–7 | 6.87 ± 0.68 Range: 3–7 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Self-discipline | 9.41 ± 0.95 Range: 6–10 | 9.26 ± 1.24 Range: 3–10 | 0.758 | 0.743 |

| Variable | Physicians (N = 41) | Residents (N = 76) | Unadjusted Model p-Value | GLZ p-Value 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnout | 51.61 ± 10.41 Range: 19–61 | 47.29 ± 11.69 Range: 19–64 | 0.032 1 | 0.280 |

| Disengagement | 26.95 ± 4.96 Range: 11–32 | 24.61 ± 5.03 Range: 9–32 | 0.017 2 | 0.269 |

| Exhaustion | 24.66 ± 6.07 Range: 8–32 | 22.68 ± 7.25 Range: 8–32 | 0.279 1 | 0.337 |

| Work addiction | 2.93 ± 0.69 Range: 1.0–3.7 | 2.12 ± 0.41 Range: 1.6–2.8 | <0.001 1 | 0.006 |

| Working excessively | 2.64 ± 0.70 Range: 1.0–3.4 | 1.73 ± 0.32 Range: 1.0–2.2 | <0.001 1 | 0.001 |

| Working compulsively | 3.21 ± 0.80 Range: 1.0–4.0 | 2.50 ± 0.52 Range: 1.6–3.4 | <0.001 1 | 0.050 |

| Stress-related growth | 28.76 ± 2.65 Range: 20–30 | 21.72 ± 4.04 Range: 14–30 | <0.001 1 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Personality Factors and Traits | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISS | N-Anx | Agg-H | Act | Sy | RDS | SDS | ||

| Burnout | rho p | −0.249 0.007 | −0.166 0.074 | −0.128 0.169 | 0.209 0.023 | 0.069 0.459 | −0.271 0.003 | 0.156 0.093 |

| Disengagement | rho p | −0.320 <0.001 | −0.261 0.005 | −0.162 0.081 | 0.252 0.006 | 0.130 0.162 | −0.331 <0.001 | 0.203 0.028 |

| Exhaustion | rho p | −0.170 0.066 | −0.105 0.258 | −0.121 0.193 | 0.136 0.143 | 0.050 0.590 | −0.189 0.041 | 0.146 0.116 |

| Work addiction | rho p | −0.351 <0.001 | −0.282 0.002 | −0.178 0.054 | 0.236 0.010 | 0.197 0.033 | −0.595 <0.001 | 0.190 0.040 |

| Working excessively | rho p | −0.366 <0.001 | −0.322 <0.001 | −0.191 00.40 | 0.226 0.014 | 0.221 0.017 | −0.618 <0.001 | 0.190 0.040 |

| Working compulsively | rho p | −0.325 <0.001 | −0.212 0.022 | −0.140 0.133 | 0.219 0.017 | 0.174 0.061 | −0.502 <0.001 | 0.189 0.041 |

| Stress-related growth | rho p | −0.394 <0.001 | −0.474 <0.001 | −0.355 <0.001 | 0.298 0.001 | 0.342 <0.001 | −0.602 <0.001 | 0.062 0.505 |

| ISS | Impulsive sensation seeking | |||||||

| N-Anx | Neuroticism–anxiety | |||||||

| Agg-H | Aggression–hostility | |||||||

| Act | Activity | |||||||

| Sy | Sociability | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tat, R.M.; Golea, A.; Vancu, G.; Grecu, M.-B.; Puticiu, M.; Hermenean, A.; Rotaru, L.T.; Butoi, M.A.; Corlade-Andrei, M.; Cimpoesu, D. Burnout, Work Addiction and Stress-Related Growth Among Emergency Physicians and Residents: A Comparative Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060730

Tat RM, Golea A, Vancu G, Grecu M-B, Puticiu M, Hermenean A, Rotaru LT, Butoi MA, Corlade-Andrei M, Cimpoesu D. Burnout, Work Addiction and Stress-Related Growth Among Emergency Physicians and Residents: A Comparative Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):730. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060730

Chicago/Turabian StyleTat, Raluca Mihaela, Adela Golea, Gabriela Vancu, Mihai-Bujor Grecu, Monica Puticiu, Andrei Hermenean, Luciana Teodora Rotaru, Mihai Alexandru Butoi, Mihaela Corlade-Andrei, and Diana Cimpoesu. 2025. "Burnout, Work Addiction and Stress-Related Growth Among Emergency Physicians and Residents: A Comparative Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060730

APA StyleTat, R. M., Golea, A., Vancu, G., Grecu, M.-B., Puticiu, M., Hermenean, A., Rotaru, L. T., Butoi, M. A., Corlade-Andrei, M., & Cimpoesu, D. (2025). Burnout, Work Addiction and Stress-Related Growth Among Emergency Physicians and Residents: A Comparative Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 730. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060730