The Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and College Students’ Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Chain Mediation Roles of Relative Deprivation and Depression and the Moderating Role of Peer Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Mediating Effect of Relative Deprivation

1.2. The Mediating Effect of Depression

1.3. The Chain-Mediating Effect of Relative Deprivation and Depression

1.4. The Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Parental Psychological Control

2.2.2. Relative Deprivation

2.2.3. Depression

2.2.4. Peer Relationships

2.2.5. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury

2.3. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

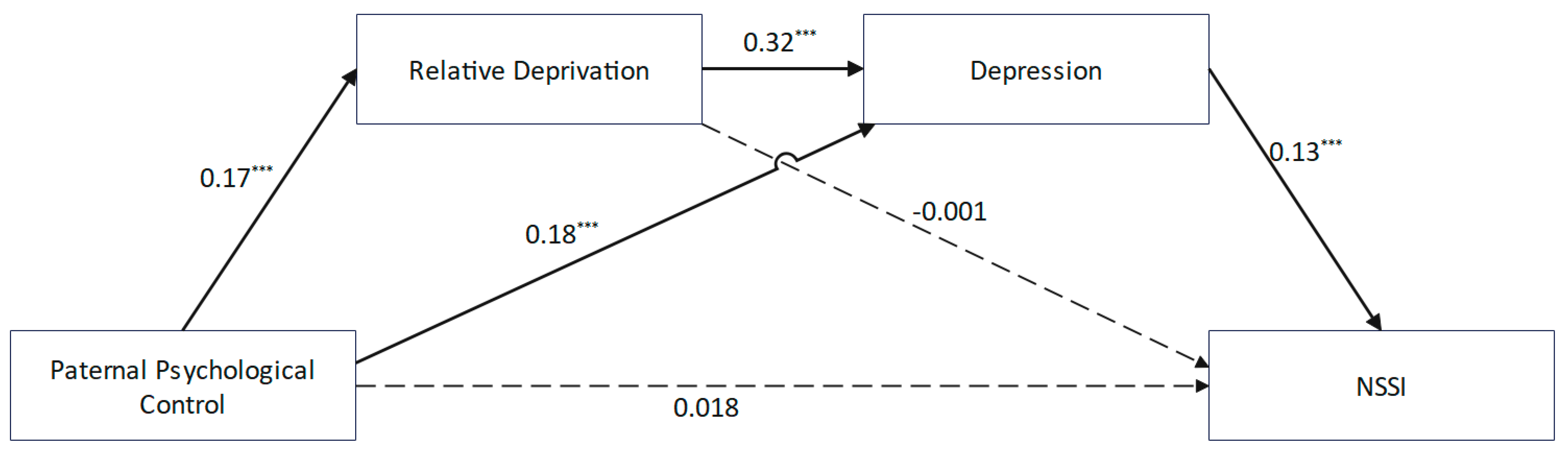

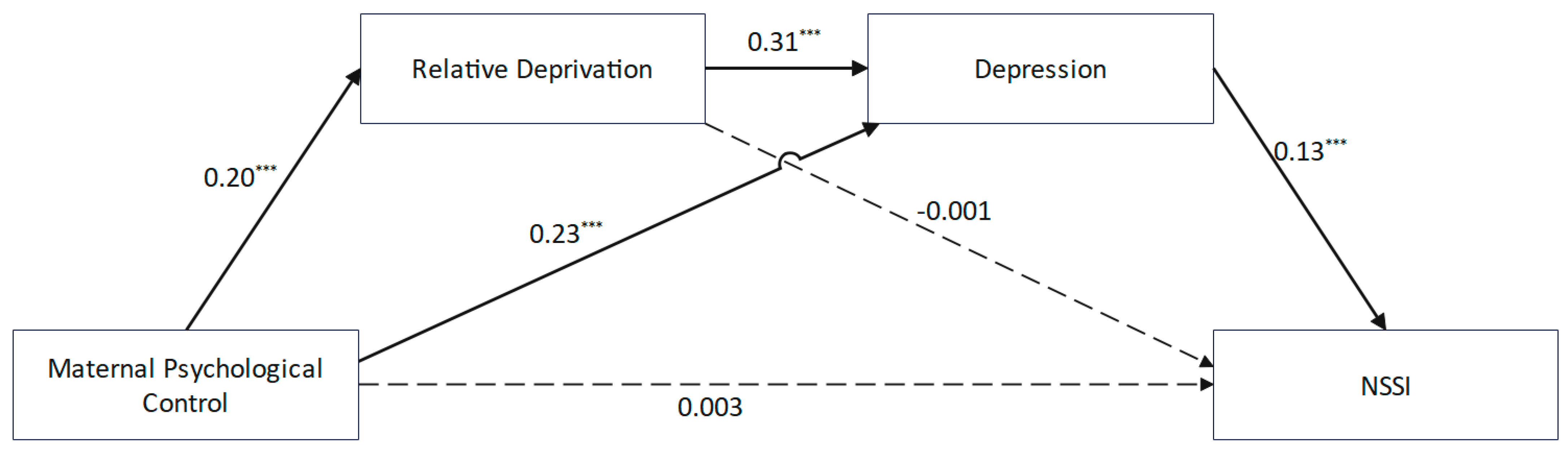

3.2. Testing for Mediation Effect

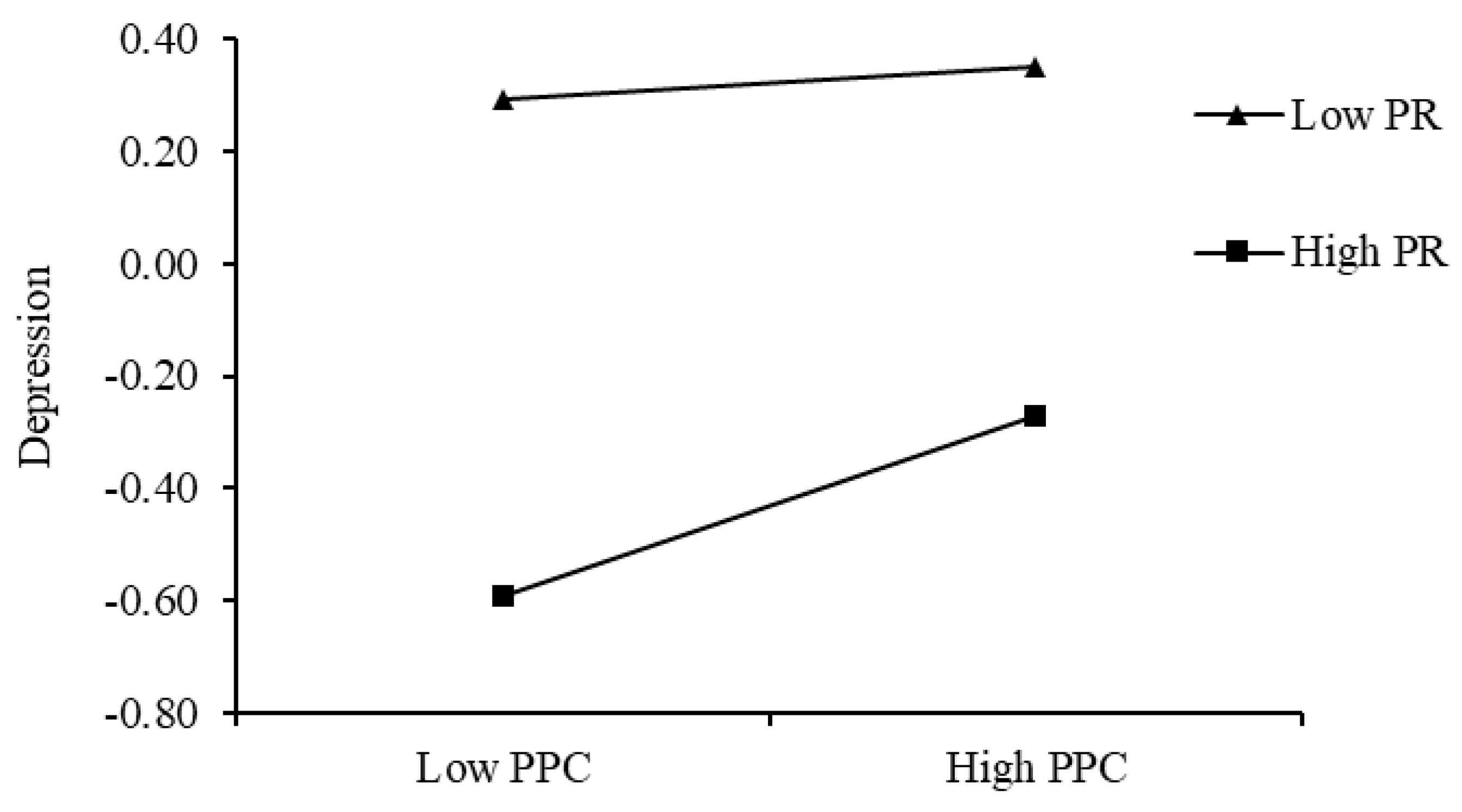

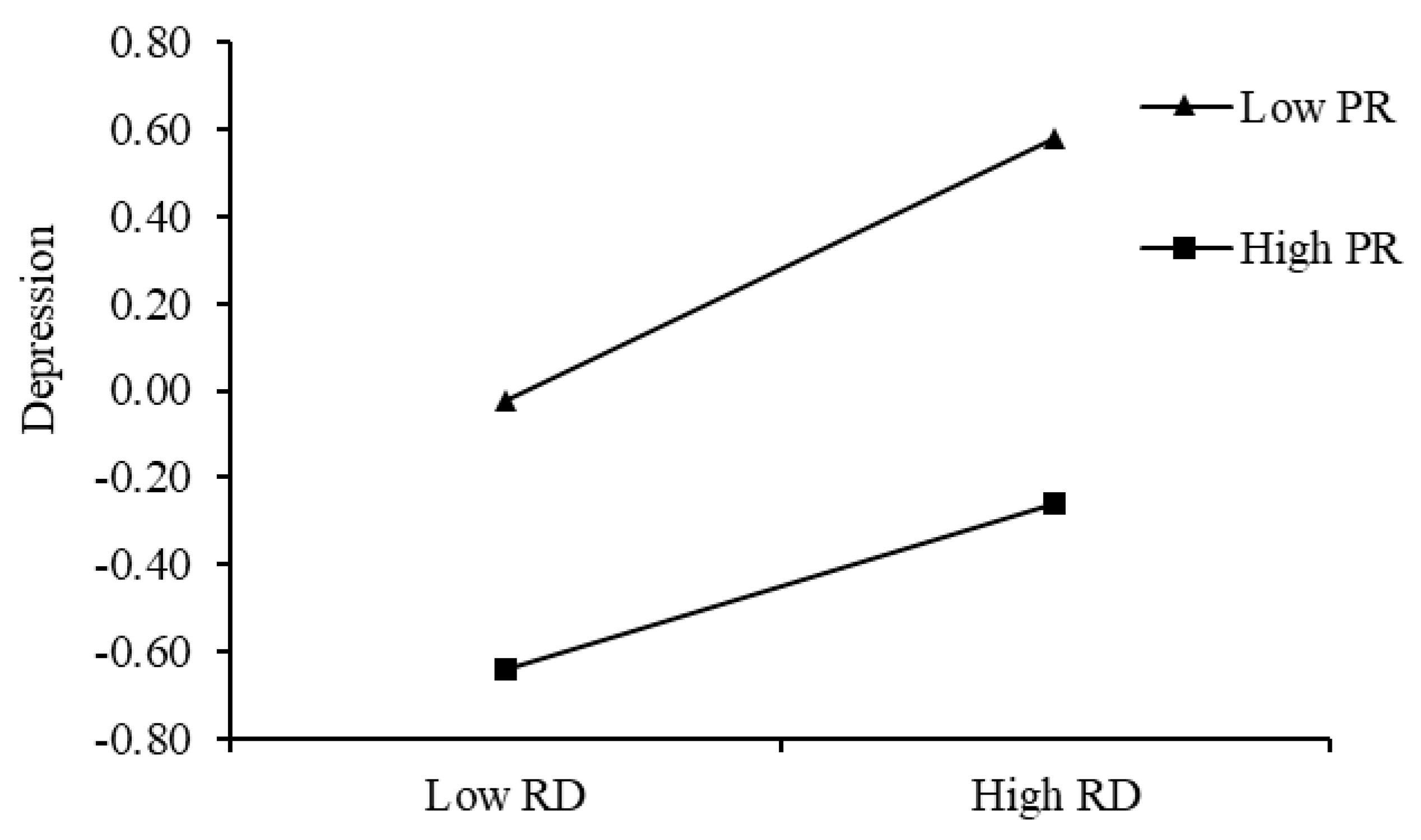

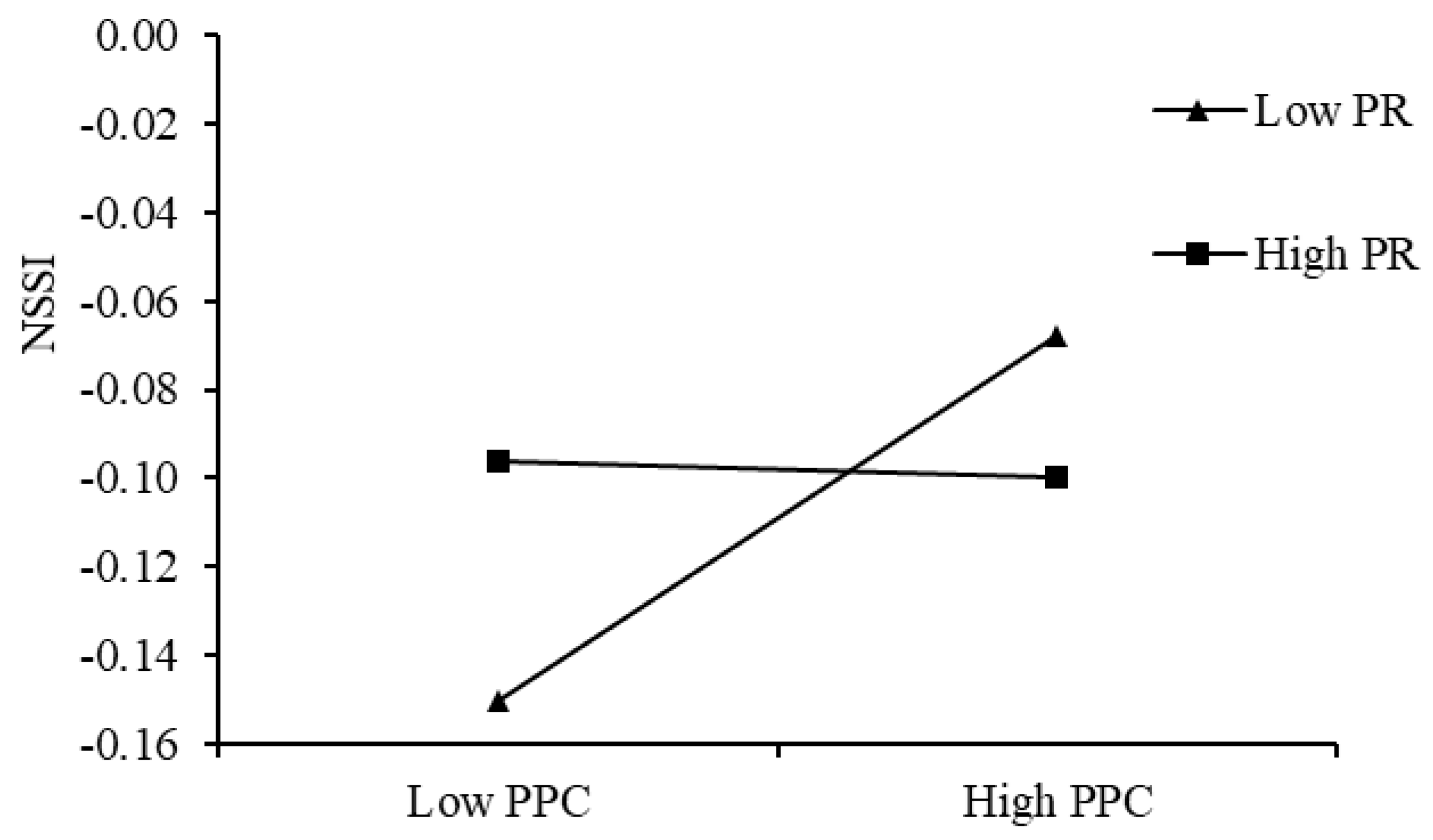

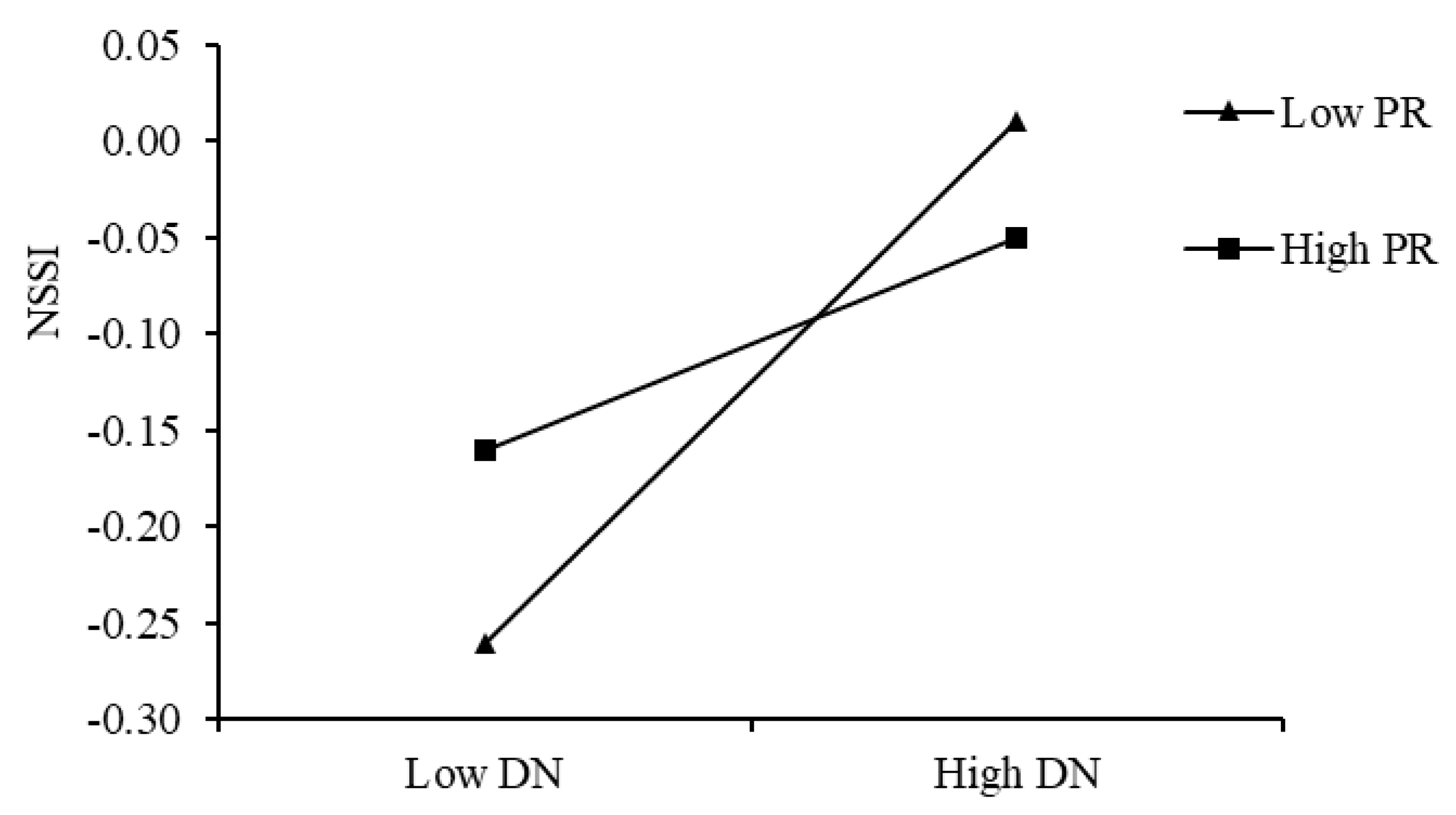

3.3. Testing for Moderated Mediation

4. Discussion

4.1. The Mediating Effect of Relative Deprivation

4.2. The Mediating Effect of Depression

4.3. The Chain-Mediating Effect of Relative Deprivation and Depression

4.4. The Moderating Effect of Peer Relationships

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abraham, M. M., & Kerns, K. A. (2013). Positive and negative emotions and coping as mediators of mother-child attachment and peer relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 59(4), 399–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67(6), 3296–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedford, O., & Yeh, K. H. (2019). The history and the future of the psychology of filial piety: Chinese norms to contextualized personality construct. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshai, S., Mishra, S., Meadows, T. J., Parmar, P., & Huang, V. (2017). Minding the gap: Subjective relative deprivation and depressive symptoms. Social Science & Medicine, 173, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby, J., Ainsworth, M., & Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759–775. [Google Scholar]

- Boyes, M. E., Mah, M. A., & Hasking, P. (2023). Associations between family functioning, emotion regulation, social support, and self-injury among emerging adult college students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(3), 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. C., & Plener, P. L. (2017). Non-suicidal self-injury in adolescence. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(3), 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. B., & Li, D. (2009). Students perceived interpersonal harmony in class and its relationship with social behaviors. Psychological Development and Education, 25(2), 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H. Y., & Cheng, C. L. (2020). Parental psychological control and children’s relational aggression: Examining the roles of gender and normative beliefs about relational aggression. The Journal of Psychology, 154(2), 159–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Zhang, Y., & Yu, G. (2022). Prevalence of mental health problems among college students in mainland China from 2010 to 2020: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychological Science, 30(5), 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, A. Y., Hartanto, A., Wan, T. S., Teo, S. S., Sim, L., & Kasturiratna, K. S. (2025). The impact of childhood sexual, physical and emotional abuse and neglect on suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury: A systematic review of meta-analyses. Psychiatry Research Communications, 5(1), 100202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiao, C., Lin, K., & Chyu, L. (2022). Perceived peer relationships in adolescence and loneliness in emerging adulthood and workplace contexts. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 794826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoforou, R., Boyes, M., & Hasking, P. (2021). Emotion profiles of college students engaging in non-suicidal self-injury: Association with functions of self-injury and other mental health concerns. Psychiatry Research, 305, 114253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chyung, Y. J., Lee, Y. A., Ahn, S. J., & Bang, H. S. (2022). Associations of perceived parental psychological control with depression, anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Marriage & Family Review, 58(2), 158–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano, A., Cella, S., & Cotrufo, P. (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., & Mckay, G. (2020). Social support, stress and the buffering hypothesis: A theoretical analysis. In Handbook of psychology and health (Vol. IV, pp. 253–267). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Depestele, L., Soenens, B., Lemmens, G. M., Dierckx, E., Schoevaerts, K., & Claes, L. (2017). Parental autonomy-support and psychological control in eating disorder patients with and without binge-eating/purging behavior and non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 36(2), 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X. X., Liang, G., Li, D. L., Liu, M. X., Yin, Z. J., Li, Y. Z., Zhang, T., & Pan, C. W. (2022). Association between parental control and depressive symptoms among college freshmen in China: The chain mediating role of chronotype and sleep quality. Journal of Affective Disorders, 317, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. (2008). The relation of adolescents’ self-harm behaviors, individual emotion characteristics and family environment factors. Central China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

- Flamant, N., Haerens, L., Mabbe, E., Vansteenkiste, M., & Soenens, B. (2020). How do adolescents deal with intrusive parenting? The role of coping with psychologically controlling parenting in internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Adolescence, 84, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, Z. H., Loh, W. N. C., Fong, Y. J., Neo, H. L. M., & Chee, T. T. (2022). Parenting behaviors, parenting styles, and non-suicidal self-injury in young people: A systematic review. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 27(1), 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, R. L., Slater, H., Jomar, K., Mitzman, S., & Taylor, P. J. (2017). Self-esteem and non-suicidal self-injury in adulthood: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 221, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guérin-Marion, C., Bureau, J., Lafontaine, M., Gaudreau, P., & Martin, J. (2021). Profiles of emotion dysregulation among college students who self-injure: Associations with parent–child relationships and non-suicidal self-injury characteristics. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 767–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Gao, Q., Wu, R., Ying, J., & You, J. (2022). Parental psychological control, parent-related loneliness, depressive symptoms, and regulatory emotional self-efficacy: A moderated serial mediation model of nonsuicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research, 26(3), 1462–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y., Li, R., & Xia, L. X. (2024). Effects of relative deprivation on change in displaced aggression and the underlying motivation mechanism: A three-wave cross-lagged analysis. British Journal of Psychology, 115(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., & Xia, L. X. (2023). Relational model of relative deprivation, revenge, and cyberbullying: A three-time longitudinal study. Aggressive Behavior, 49(4), 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, C. A., Stewart, S. L., & Willoughby, T. (2012). Examining the link between nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior: A review of the literature and an integrated model. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, P., & Cui, M. (2020). Helicopter parenting and college students’ psychological maladjustment: The role of self-control and living arrangement. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J., Zhang, D., Chen, Y., Yu, C., Zhen, S., & Zhang, W. (2022). Parental psychological control, psychological need satisfaction, and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The moderating effect of sensation seeking. Children and Youth Services Review, 136, 106417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L., Zhang, J., Duan, W., & He, L. (2021). Peer relationship increasing the risk of social media addiction among Chinese adolescents who have negative emotions. Current Psychology, 42, 7673–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W., Jung, E., Hadi, N., & Kim, S. (2024). Parental control and college students’ depressive symptoms: A latent class analysis. PLoS ONE, 19(2), e0287142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J., & Wang, P. (2020). Does early peer relationship last long? The enduring influence of early peer relationship on depression in middle and later life. Journal of Affective Disorders, 273, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karreman, A., & Bekker, M. H. (2012). Feeling angry and acting angry: Different effects of autonomy-connectedness in boys and girls. Journal of Adolescence, 35(2), 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiekens, G., Hasking, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Auerbach, R. P., Bantjes, J., Benjet, C., Boyes, M., Chiu, W. T., Claes, L., & Cuijpers, P. (2023). Non-suicidal self-injury among first-year college students and its association with mental disorders: Results from the World Mental Health International College Student (WMH-ICS) initiative. Psychological Medicine, 53(3), 875–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H., Yang, Y., Zhu, T., Zhang, X., & Dang, J. (2024). Network analysis of the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury, depression, and childhood trauma in adolescents. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S., Zhao, X., Zhao, F., Liu, H., & Yu, G. (2023). Childhood maltreatment and adolescent cyberbullying perpetration: Roles of individual relative deprivation and deviant peer affiliation. Children and Youth Services Review, 149, 106957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, X., Wang, H., Ni, X., & Yu, C. (2024). Family economic hardship and non-suicidal self-injury among chinese adolescents: Relative deprivation as a mediator and self-esteem as a moderator. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Wan, L., Liu, B., Jia, C., & Liu, X. (2022). Depressive symptoms mediate the association between maternal authoritarian parenting and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Affective Disorders, 305, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Xu, Z., Li, X., Song, R., Wei, N., Yuan, J., Liu, L., Pan, G., & Su, H. (2024). The association between the sense of relative deprivation and depression among college students: Gender differences and mediation analysis. Current Psychology, 43(18), 16421–16430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A. (2012). Relative deprivation and social adaption: The role of mediator and moderator. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(3), 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J., Bureau, J., Yurkowski, K., Fournier, T. R., Lafontaine, M., & Cloutier, P. (2016). Family-based risk factors for non-suicidal self-injury: Considering influences of maltreatment, adverse family-life experiences, and parent–child relational risk. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, S., Yin, X., Pan, B., Chen, H., Dai, C., Tong, C., Chen, F., & Feng, X. (2024). Understanding comorbidity between non-suicidal self-injury and depressive symptoms in a clinical sample of adolescents: A network analysis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(2), 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otte, S., Streb, J., Rasche, K., Franke, I., Segmiller, F., Nigel, S., Vasic, N., & Dudeck, M. (2019). Self-aggression, reactive aggression, and spontaneous aggression: Mediating effects of self-esteem and psychopathology. Aggressive Behavior, 45(4), 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, T., & Choung, Y. (2020). Relative deprivation and suicide risk in South Korea. Social Science & Medicine, 247, 112815. [Google Scholar]

- Paley, B., & Hajal, N. J. (2022). Conceptualizing emotion regulation and coregulation as family-level phenomena. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 25(1), 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C., Wang, L. X., Guo, Z., Sun, P., Yao, X., Yuan, M., & Kou, Y. (2024). Bidirectional longitudinal associations between parental psychological control and peer victimization among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(4), 967–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, S. W., White, T. R., Carter, D. B., & Horner, M. E. F. (2016). Parental support and psychological control in relation to African American college students’ self-esteem. Journal of Pan African Studies, 9(4), 199–219. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, C., Favara, M., Hittmeyer, A., Scott, D., Jiménez, A. S., Ellanki, R., Woldehanna, T., Duc, L. T., Craske, M. G., & Stein, A. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression symptoms of young people in the global south: Evidence from a four-country cohort study. BMJ Open, 11(4), e049653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinstein, M. J., & Giletta, M. (2020). Future directions in peer relations research. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(4), 556–572. [Google Scholar]

- Roach, A. (2018). Supportive peer relationships and mental health in adolescence: An integrative review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(9), 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shek, D. T. (2005). Perceived parental control and parent–child relational qualities in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Sex Roles, 53, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. J., & Huo, Y. J. (2014). Relative deprivation: How subjective experiences of inequality influence social behavior and health. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H. J., Pettigrew, T. F., Pippin, G. M., & Bialosiewicz, S. (2012). Relative deprivation: A theoretical and meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(3), 203–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, S. H., & Rapee, R. M. (2016). The etiology of social anxiety disorder: An evidence-based model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 86, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swearer, S. M., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. American Psychologist, 70(4), 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P. J., Jomar, K., Dhingra, K., Forrester, R., Shahmalak, U., & Dickson, J. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapar, A., Collishaw, S., Pine, D. S., & Thapar, A. K. (2012). Depression in adolescence. The Lancet, 379(9820), 1056–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., Deng, X., Tong, W., & He, W. (2025). Relative deprivation and aggressive behavior: The serial mediation of school engagement and deviant peer affiliation. Children and Youth Services Review, 168, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Meng, W. (2024). Adverse childhood experiences and deviant peer affiliation among Chinese delinquent adolescents: The role of relative deprivation and age. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1374932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C., Liu, B., An, X., & Wang, Y. (2025). Longitudinal associations between relative deprivation and non-suicidal self-injury in early adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 16, 1553740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., Zhang, H., Chen, J., Chen, J., Liu, Z., Cheng, Y., Yuan, T., & Peng, D. (2023). Potential mechanisms of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in major depressive disorder: A systematic review. General Psychiatry, 36(4), e100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B., Cai, G., Xiong, C., & Huang, J. (2021). Relative deprivation and game addiction in left-behind children: A moderated mediation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 639051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., & Yang, L. (2025). Parental psychological control, state self-compassion, and depression in adolescents: Direct and indirect associations among developmental trajectories. Current Psychology, 44, 1906–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B., Zhang, W., Sun, L., Jiang, C., Zhou, Y., & He, K. (2023). Relationship between alexithymia, loneliness, resilience and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with depression: A multi-center study. BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J., & Tao, M. (2013). Relative deprivation and psychopathology of Chinese college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(3), 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., & Peng, L. (2021). Feeling matters: Perceived social support moderates the relationship between personal relative deprivation and depressive symptoms. BMC Psychiatry, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H., Liu, J., & Deng, C. (2024). Trajectories of perceived parental psychological control and the longitudinal associations with chinese adolescents’ school adjustment across high school years. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53(9), 2060–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H., Luo, Y., Shi, L., & Gong, J. (2023). Exploring psychological and psychosocial correlates of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide in college students using network analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 336, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q., Cheong, Y., Wang, C., & Tong, J. (2023). The impact of maternal and paternal parenting styles and parental involvement on Chinese adolescents’ academic engagement and burnout. Current Psychology, 42(4), 2827–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H. (1998). The developmental functions of peer relationships and their influencing factors. Psychological Development and Education, (2), 39–44. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Age | −0.04 | 1 | ||||||

| 3. PPC | −0.16 ** | 0.01 | 1 | |||||

| 4. MPC | −0.15 ** | −0.02 | 0.77 *** | 1 | ||||

| 5. RD | −0.09 ** | −0.07 * | 0.18 *** | 0.21 *** | 1 | |||

| 6. DN | −0.09 ** | −0.07 * | 0.25 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.37 *** | 1 | ||

| 7. PR | 0.08 ** | 0.01 | −0.33 *** | −0.35 *** | −0.28 *** | −0.45 *** | 1 | |

| 8. NSSI | −0.04 | −0.10 ** | 0.12 *** | 0.11 *** | 0.13 *** | 0.34 *** | −0.15 *** | 1 |

| M ± SD | 19.26 ± 0.99 | 2.17 ± 1.02 | 1.95 ± 1.03 | 2.28 ± 1.02 | 1.55 ± 0.56 | 3.89 ± 0.94 | 0.10 ± 0.46 |

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC → RD → NSSI | −0.0001 | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.004 | |

| PPC → DN → NSSI | 0.023 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 0.035 | 47.91% |

| PPC → RD → DN → NSSI | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 14.58% |

| Total Indirect effect | 0.03 | 0.006 | 0.018 | 0.044 | 62.49% |

| Direct effect | 0.018 | 0.01 | −0.005 | 0.04 | 37.5% |

| Total effect | 0.048 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 100% |

| Effect | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI | Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MPC → RD → NSSI | 0.0002 | 0.002 | −0.005 | 0.005 | |

| MPC → DN → NSSI | 0.03 | 0.007 | 0.018 | 0.045 | 72.38% |

| MPC → RD → DN → NSSI | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 20.46% |

| Total Indirect effect | 0.039 | 0.007 | 0.025 | 0.05 | 92.85% |

| Direct effect | 0.003 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 7.15% |

| Total effect | 0.042 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 100% |

| Variables | Model 1 (RD) | Model 2 (DN) | Model 3 (NSSI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | |

| Gender | −0.11 | −1.95 | [−0.22, 0.001] | −0.07 | −1.46 | [−0.17,0.02] | −0.004 | −0.19 | [−0.05, 0.04] |

| Age | −0.06 | −2.37 * | [−0.12, −0.01] | −0.05 | −2.18 * | [−0.17, −0.005] | −0.04 | −3.22 ** | [−0.06, −0.01] |

| PPC | 0.09 | 3.21 ** | [0.03, 0.15] | 0.08 | 3.09 ** | [0.03, 0.13] | 0.02 | 1.85 | [−0.001, 0.05] |

| PR | −0.25 | −8.40 *** | [−0.31, −0.19] | −0.35 | −12.98 *** | [−0.40, −0.30] | 0.003 | 0.26 | [−0.02, 0.03] |

| RD | 0.23 | 8.71 *** | [0.18, 0.29] | 0.001 | 0.05 | [−0.02, 0.02] | |||

| DN | 0.12 | 8.38 *** | [0.09, 0.14] | ||||||

| PPC × PR | 0.04 | 1.75 | [−0.005,0.10] | 0.06 | 2.39 * | [0.01, 0.11] | −0.02 | −2.0 * | [−0.04, −0.001] |

| RD × PR | −0.05 | −2.16 * | [−0.09, −0.005] | −0.003 | −0.30 | [−0.02, 0.02] | |||

| DN × PR | −0.04 | −3.66 *** | [−0.06, −0.02] | ||||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.14 | ||||||

| F | 24.97 *** | 63.67 *** | 20.18 *** |

| Variables | Model 1 (RD) | Model 2 (DN) | Model 3 (NSSI) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | β | t | 95% CI | |

| Gender | −0.10 | −1.83 | [−0.21, 0.007] | −0.06 | −1.14 | [−0.15, 0.04] | −0.01 | −0.48 | [−0.06, 0.03] |

| Age | −0.06 | −2.27 * | [−0.12, −0.01] | −0.06 | −2.09 * | [−0.10, −0.003] | −0.04 | −3.18 ** | [−0.06, −0.01] |

| MPC | 0.12 | 4.10 *** | [0.06, 0.18] | 0.14 | 5.05 *** | [0.08, 0.18] | 0.004 | 0.32 | [−0.02, 0.03] |

| PR | −0.24 | −7.94 *** | [−0.30, −0.18] | −0.33 | −12.15 *** | [−0.38, −0.28] | −0.004 | −0.33 | [−0.03, 0.02] |

| RD | 0.23 | 8.58 *** | [0.18, 0.28] | 0.0007 | 0.05 | [−0.02, 0.02] | |||

| DN | 0.12 | 8.33 *** | [0.09, 0.14] | ||||||

| MPC × PR | 0.04 | 1.26 | [−0.02, 0.09] | 0.02 | 0.84 | [−0.03, 0.07] | −0.01 | −0.47 | [−0.03, 0.02] |

| RD × PR | −0.04 | −1.95 | [−0.09,0.002] | −0.01 | −0.45 | [−0.02, 0.02] | |||

| DN × PR | −0.04 | −3.47 *** | [−0.06, −0.02] | ||||||

| R2 | 0.10 | 0.28 | 0.13 | ||||||

| F | 25.89 *** | 65.71 *** | 19.27 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, S.; Bao, Q. The Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and College Students’ Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Chain Mediation Roles of Relative Deprivation and Depression and the Moderating Role of Peer Relationships. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060729

Cui S, Bao Q. The Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and College Students’ Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Chain Mediation Roles of Relative Deprivation and Depression and the Moderating Role of Peer Relationships. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):729. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060729

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Sachula, and Qiang Bao. 2025. "The Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and College Students’ Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Chain Mediation Roles of Relative Deprivation and Depression and the Moderating Role of Peer Relationships" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060729

APA StyleCui, S., & Bao, Q. (2025). The Relationship Between Parental Psychological Control and College Students’ Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: The Chain Mediation Roles of Relative Deprivation and Depression and the Moderating Role of Peer Relationships. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 729. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060729