Perceptions of Causes, Consequences, and Solutions of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Mexican Women Survivors of IPV: A Qualitative Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Participants and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participants

2.3. Study Design

2.4. Procedures

2.5. Sociodemographic Variables

2.6. Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Results of the Qualitative Analysis

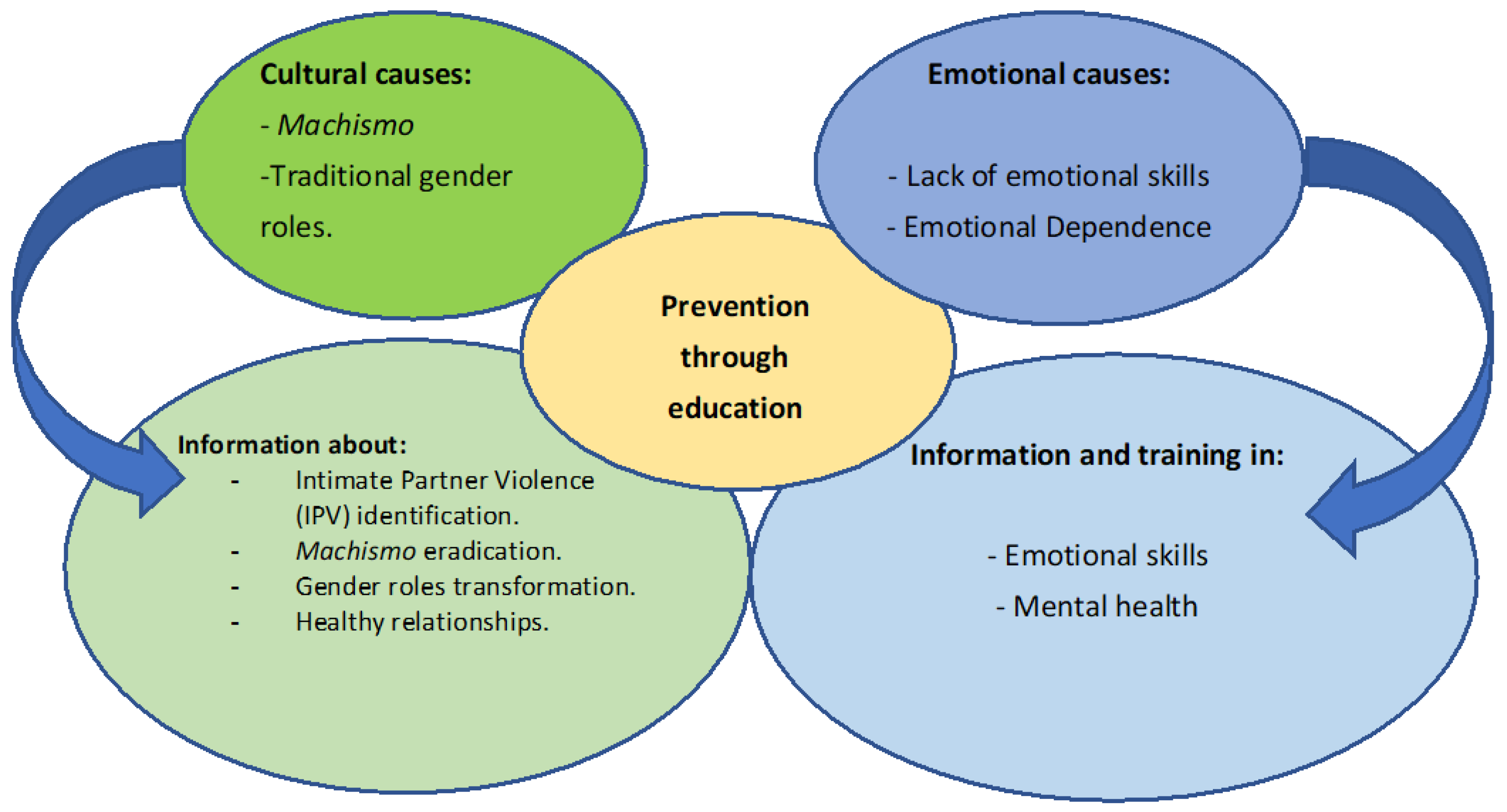

3.2. Perceptions of Causes of IPV

- (a)

- Transgenerational violence: This refers to witnessing violence between one’s parents during childhood and having experienced it. Quote (P30, 34y): “If the son witnessed his father hitting his mother, then the son will do the same […], the upbringing from great-grandparents to the present is reflected”. (P6, 53y): “The mother (her mother in law), the advice she gave to both daughters and daughters-in-law was that, if you are about to answer you husband, take a mouthful of water and don’t speak”.

- (b)

- Cultural norms and traditional gender roles: This code refers to the fact that women are in charge of domestic work and attend to the family’s men: (P13, 70y): “Since the 9 years my mom told me you are in charge of your brother’s clothes […] and I was a very beaten girl, precisely for that reason, because (according to my mother) I disrespected my brothers”. (P26, 30y): “Because at home I was taught the exact opposite, you shut up, obey, respect, and do what your partner does”.

- (c)

- Machismo: This is the idea that men should command the relationship and have the right to control and subjugate women. The following quotes exemplify this: (P32, 52y): “Machismo has always existed and will never disappear […], right now we are here, in a little while they kidnap us, they kill us”. (P24, 56y): “It is the Machismo isn’t it? The fact that because men are men, they have the privilege to command, order or even hit”. (P9, 50y): “Today, there are women who stay at home doing housework and the man feels superior because of that and then his dominance begins, but when the woman goes out (to work) then a rivalry is established […], who pays is who commands”.

- (a)

- Lack of emotional abilities: This refers to a lack of self-esteem, fear of leaving one’s partner, and a lack of assertiveness in setting limits from the beginning of the relationship. Quote (P20, 34y): “At 16 you don’t know what a limit is, you don’t know any other love than one who comes and talks you nicely […] it’s said to be easy to set limits, but it is not because you are in love with that person […] as long as you don’t have the information, as long as you don’t have the psychological support, you will never understand what a limit is”. Quote (P3,45y): “At first one thinks it is normal […] that was my first mistake, I shouldn’t have get quiet since the beginning”.

- (b)

- Emotional dependence: This refers to the emotional inability to leave one’s partner because of customs, need for affection, or fear of being alone. Quote (P6, 53y): “It is what hooks us and it is in the name of love that one endures everything”; (P5, 55y): “Before, even though he fought with me and no matter what he did to me and my children […] I forgave him and still felt save with him, I felt that he loved me”.

- (c)

- Trauma and emotional deficiencies in childhood: This code refers to untreated trauma in childhood in relation to current emotional deficiencies, witnessing violence at home that was not solved with therapy, and the lack of a masculine figure during infancy, which is compensated with an intimate partner. Quote (P11, 25y): “Many women seek to fill the absence of a male figure, even when it means enduring violence, it’s as if we can’t let go of something we feel is necessary, even if it hurts us”; (P22, 24y): “If we were not given that love, we were not given that psychological attention since we were child, then obviously we grow up with those needs”.

- (a)

- Lack of information about IPV and healthy relationships: This relates to providing information from childhood about what IPV is and how a healthy relationship should be. Quote (P2, 64y): “At beginning you are deeply in love and you think these are normal things […], one believes that it is normal, that one should be quite and endure”. (P6, 53y): “I didn’t know it was violence, until I went to therapy”.

- (b)

- Lack of information about mental health and emotional abilities: This is exemplified in the following quote (P14, 29y): “One of the factors today is the lack of access to information about psychology and mental health, knowing our limits and letting other people know about their limits about others and how to recognize the toxicity of harmful actions and relationships”. Quote (P30, 34y): “As long as you don’t have the information, as long as you don’t have psychological support, you will never understand what a limit is”.

- (a)

- Economic dependence: This code represents poverty and economic dependence on the partner. Quote (P9, 50y): “(The cause of IPV) It would be the economic dependence and the education”; (P2, 64y): “I couldn’t, I was stunned, I was scared, I was afraid. I couldn’t leave, I had no money […] he bought me clothes and all that stuff, it was total control”.

- (b)

- Inequality in access to job opportunities: This code refers to the disadvantage of mothers with respect to men in getting a job, as exemplified in the following quote (P29, 28y): “The woman falls because she has to take care of the children because she has no financial support […], and even though you try and try, it is impossible with the schedules they set, with the transportation, the nannies”.

- (a)

- Children’s dependence: This code refers to the fact that many women victims of IPV have children who depend on them, and they do not have the means to raise them. Quote (P28, 54y): “I never got away from it because I have two children and I stopped to think: where was I going to take them to live.? […]. I had never had a stable or good job, so I depended on the house and the money he gave me, there, education and financial independence would be what would help you get out of that”. (P29, 28y): “Because we have to save, take care of the children, because you don’t have financial support”.

- (b)

- Social and familial judgments: This code refers to the lack of social support that many women victims of IPV experience, as exemplified by the following quote (P26, 30y): “Many times it is your own family or friends who tell you: not to be exaggerated or how toxic you are”. (P8, 43y): “I went with my relatives and it was worse, now I suffered violence from the family”.

- (a)

- Alcohol abuse: This code refers to the relationship between alcohol addiction and abuse through IPV, and it is examplified by the following quotes: (P14, 29y): “My mom has anxiety because she suffered trauma from my dad who liked alcohol […] she didn’t heal the trauma she had with my grandfather who was also alcoholic”. (P21, 30y): “He is a psychopath … and has taken psychiatric drugs … and also consumed alcohol, so he got really bad”.

- (b)

- Drug consumption: This code refers to the relationship of drug addiction and consumption with IPV, as exemplified in the following quote: (P10, 25y): “My ex-partner is a drug addict and that triggered a violence that transformed him”. (P22, 24y): “He takes drugs even though he says he doesn’t and he became very aggressive”.

3.3. Perceptions of Consequences of IPV

- (a)

- Emotional disorders: This subtheme included anxiety, depression, suicide attempts, self-blame, suicidal ideation, panic attacks, and mental disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder. Quote (P26, 30y): “I suffer from insomnia, anxiety, and depression, I have suicide thoughts constantly, it is a constant fight. I’m on medication and therapy, but it was something that frustrated all my life”.

- (b)

- Emotional isolation: This refers to the fact that victims of IPV are isolated from their support network by fear of their partner, by being locked in the house doing housework, and by the inability to trust people. Quote (P27, 29y): “I became very afraid of going out on the street because of his threats, that made it impossible for me to have a stable job … I lost all my friends”. (P6, 53y): “I couldn’t go to visit anyone, I had to stay at home … the neighbors didn’t know me … all my emotions were silent”.

- (a)

- Physical injuries: This is exemplified in the following quotes: (P17, 24y): “My last partner threw me while I was pregnant. I spent two months in the hospital”. (P6, 53y): “He hit me on my arms. They were so bruised, I couldn’t move them”.

- (b)

- General health effects: This code refers to the appearance of psychosomatic illness or worsening of physical illness because of the stress experienced due to IPV. Quote (P2, 64y): “I feel like all of that was landing the diseases on my body”. (P6, 53y): “I also became physically ill”.

- (a)

- Stigmatization: This refers to criticism and social judgment for being a victim of IPV. Quote (P28, 54y): “My son asked me how was it possible that I was not able to get him [my husband] out of the house [with a complaint] … because I am afraid and shame with others, that noticed it”; (P5, 55y): “I blinded myself and said to myself I am crazy […] well, through religious situations one makes the decision to forgive and to fall into the same thing again”.

- (b)

- Breaking of social relationships: This refers to the loss of one’s social network because of violence. Quote (P29, 28y): “It broke my structure, I had to change my friendships, my job, and residency, emotionally and structurally it did break me all over”. (P11, 25y): “My work and social life declined, I had to move to a new workplace, and most of my friends stopped talking to me”.

- (a)

- Loss of resources: This code refers to the loss of personal belongings, documents, and the house where the victim lived together with the partner. Quote (P28, 54y): “I experienced all kinds of violence, the last thing he did was to break furniture, the dresser, the closet, he destroyed everything”. (P32, 52y): “He had the nerve to throw away my clothes, he ransacks my closet, take my documents and now he is the one asking me for a compensation”.

- (b)

- Loss of job opportunities: This code refers to the loss of job opportunities as a consequence of IPV; this is because the victim had to change her job, because she had mental health conditions that prevented her from having a job, or the aggressor did not allow the victim to work. Quote (P26, 30y): “To find a job with depression and anxiety I have to knock on many doors”. Quote (P6, 53y): “(He) did not want me to work”.

- (c)

- Being economically independent: This code refers to the need to be economically independent after an IPV experience. The following quotes exemplify this: (P2, 64y): “To get a job as an elderly woman, it is not so easy”; (P3, 45y): “My satisfaction is having started working at 45 years old without work experience”.

- (a)

- Impact of IPV on the children: This code refers to the physical and psychological impact of IPV on children. The following quotes exemplify this: (P13, 70y): “My daughter (of 45 years old) told me: it is that my dad is harassing me”; (P23, 35y): “My son started acting violently towards his siblings, toward me and his father”; (P30, 34y): “My daughter was badly beaten because her father hit her”, “My daughter doesn’t show feelings, she doesn’t show love, because of everything she lived with her father”.

- (b)

- Loss of contact with their children: This code refers to the fact that many aggressors take children away from their mothers using lies and economic influence, as exemplified in the following quote: (P30, 34y): “They are going to adjust two years that I have not seen my son because his father took him away from me alleging that I have childish mistreatment towards him”; (P21, 30y): “He takes my daughter away and I am devastated. I didn’t see my daughter for 4 months”.

- (a)

- Ineffectiveness of the legal system: This code refers to delayed legal processes and failures in laws: (P27, 29y): “When I started to investigate why the processes were not moving forward I realized that many processes do not move forward because the laws that should protect us are poorly written, so that makes it impossible for the prosecutor’s office and the people who are there to assist us, to do justice”. Quote (P17, 24y): “They were going to give her protective measures but they never went to check her home … They found her dead”.

- (b)

- Legal impunity: This code refers to the legal impunity that perpetrators of IPV have in the Mexican justice system, while victims lack protection and an opportunity to repair the damage: (P27, 29y): “They feel untouchable, they say: I did her of everything and all ended up with 3000 pesos … so there really is no tangible consequence”. (P26, 30y): “A year later (to file a complaint) they may be call you and tell you The file wasn’t processed […] the aggressor is still out there, he is a predator […] they are not protecting us from the aggressor.”

3.4. Perceptions of Solutions to IPV

- (a)

- Educational programs in schools: This code refers to the need for education about violence and IPV, as well as the development of skills in schools: (P10, 25y): “If schools talked about this, children would identify what is wrong, not only with women but with how we are treated overall”. (P14, 29y): “That it was an extra class on managing emotions … setting limits … managing the economy”.

- (b)

- Training in personal skills: This code refers to the need to increase emotional skills in children and adults: (P10, 25y): “To perform a course to train girls to feel able to be alone, without the ideology that a man is going to come and help her”; (P9, 50y): “I have to set limits and you have to set your limits too (in a relationship)”.

- (c)

- Culture of peace at home: This code refers to the importance of education against violence at home: (P8, 43y): “The respect for all live beings […] and public spaces […] to create a better society”. (P29, 28y): “From homes, values could be taught”.

- (d)

- Preventive programs in social media: This code refers to carrying out social media programs to prevent IPV. Quote (P13, 70y): “This should be preventative, I return to the mass media like television, to give information about IPV”. (P5, 55y): “Those programs focused on prevention be made … such as radio and television”.

- (a)

- Psychological prevention: This code refers to the need for psychological studies of couples before they marry to identify violent behaviors and the need for psychological therapy from childhood. Quotes: (P23, 35y): “It would be great that by law, they were required to undergo a psychological study at the time of getting married”; (P14, 29y): “That the child from an early age has psychological therapy, and the parents have it at the same time”.

- (b)

- Psychological therapy: This code refers to the need to treat personal and relationship issues with a psychologist. Quote (P23, 35y): “When we are in a relationship one must undergo personal and couple therapy”. (P11, 25y): “To start a new relationship, you must to heal the first one because that creates a lot of insecurity. You must to work on your self-esteem to see that you are worth a lot. We are not an object. We are a human being who is worth a lot”.

- (a)

- Improving legal advice: This refers to the need to improve legal information in governmental institutions related to divorce and IPV complaints. Quotes (P22, 24y): “I would like to know how far I can get out of there, how far and why I can run from there”; (P9, 50y): “The last advisor I had is not qualified, as if he doesn’t want to move forward in the process”.

- (b)

- Training for legal authorities: This code refers to the importance of training police and legal staff in IPV situations, increasing empathy, and simplifying processes. Quote (P27, 29y): “They (the authorities) should be more empathic. When one goes to report, the same women treat the woman who is going to make the report badly. They also demand too much. If you go with a bruise on your face, a bruise on your arm, or a bruise on your leg, it is very little to file a complaint. You must to go almost with one foot in the box so that they can accept your complaint”. Quote (P9, 50y): “There should be more and better trained (victims assistance centers)”.

- (c)

- Improving public policies: This code refers to improving public policies related to IPV. Quote (P29, 28y): “Since laws are not very specific and clear, the institutions cannot do anything … For example, the law against vicarious violence was just recently approved and there is not even a route, there is no access route”; (P26, 30y): “The law is more on the side of men”.

- (a)

- Economic independence: This code refers to the need to promote economic independence from a young age. Quote: (P10, 25y): “Some kind of help, that there is a course where we are thought how to generate, it would have been different …”; (P28, 54y): “It would be the education, the economic independence that would help you to get out of that”.

- (b)

- Support networks among women: This code refers to the need to increase the number of women’s support groups. If there were more groups of women sharing experiences, many would feel encouraged to leave these situations. Quote (P2, 64y): “In the workshops we have done, we have formed real support groups”. (P11, 25y): “Part of raising awareness has to do with support networks, that we all have a support network where we feel safe”.

- (c)

- Leaving an aggressive partner: This code refers to the fact of leaving one’s partner. Quotes (P16, 35y): “I would say it’s better to stay away from the aggressor, because he will always be there, abusing you”. (P30, 34y): “So after four (suicide) attempts, I said well … what do I have to do? To get away, its over”.

- (a)

- Changing gender roles: This code refers to the change in the concept that men are the head of the family. Quote: (P8, 43y): “Many times the society makes them like that […] they say a man is strong and don’t cry, a man hits, many women are more sexist [than men], they (men) can also be creative, be kind, cry”. (P16, 35y): “That has my mother, that makes us women see as we are ones obliged to help at home and that men are not obliged to do it, so they have a machismo”.

- (b)

- Men can also suffer from IPV: This code refers to the fact that, due to traditional gender roles, many men that suffer from IPV from a woman do not report it. Quote (P31, 49y): “I know a person that is violented by his wife”.

- (c)

- IPV with sexual diversity: This code refers to the lack of help groups for women in homosexual relationships who have been abused and the lack of availability of groups for aggressive women in institutions. Quote: (P14, 29y): “My psychologist told me: You know that I have 4 more cases plus yours of (aggressive) girls (in homosexual relationships)”.

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abel, K. M., Heuvelman, H., Rai, D., Timpson, N. J., Sarginson, J., Shallcross, R., Mitchell, H., Hope, H., & Emsley, R. (2019). Intelligence in offspring born to women exposed to intimate partner violence: A population-based cohort study. Wellcome Open Research, 4, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Admassu, M., Benova, L., Nöstlinger, C., Semaan, A., Christou, A., Nieto-Sanchez, C., Laga, M., Endriyas, M., & Delvaux, T. (2024). Uncovering community needs regarding violence against women and girls in southern Ethiopia: An explorative study. PLoS ONE, 19(6), e0304459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agoff, C., & Herrera, C. (2019). Entrevistas narrativas y grupos de discusión en el estudio de la violencia de pareja. Estudios Sociológicos De El Colegio De México, 37(110), 309–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoff, C., Herrera, C., & Castro, R. (2007). The weakness of family ties and their perpetuating effects on gender violence. Violence Against Women, 13(11), 1206–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldarondo, E., Kaufman-Kantor, G. K., & Jasinski, J. L. (2002). Risk marker analysis for wife assault in Latino families. Violence Against Women, 8, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsina, E., Browne, J. L., Gielkens, D., Noorman, M. A. J., & De Wit, J. B. (2023). Interventions to prevent intimate partner violence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Violence Against Women, 30(3–4), 953–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azziz-Baumgartner, E., McKeown, L., Melvin, P., Dang, Q., & Reed, J. (2011). Rates of femicide in women of different races, ethnicities, and places of birth: Massachusetts, 1993–2007. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(5), 1077–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Burgos, L., Valdez-Santiago, R., Híjar, M., Del Rio-Zolezzi, A., Rojas-Martínez, R., & Medina-Solís, C. E. (2009). Factors associated with severity of intimate partner abuse in Mexico: Results of the first national survey of violence against women. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 100(6), 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabras, C., Mondo, M., Diana, A., & Sechi, C. (2020). Relationships between Trait Emotional Intelligence, mood states, and future orientation among female Italian victims of Intimate Partner Violence. Heliyon, 6(11), e05538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, R., Ramisetty-Mikler, S., & McGrath, C. (2004). Acculturation, drinking and intimate partner violence among Hispanic couples in the U.S.: A longitudinal analysis. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 26(1), 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, J. R. (2024). A systematic review of barriers to formal supports for women who have experienced intimate partner violence in Spanish-Speaking countries in Latin America. Trauma Violence & Abuse, 25(1), 526–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Ma, N., Kong, Y., Chen, Z., Niyi, J. L., Karoli, P., Msuya, H. M., Zemene, M. A., Khan, M. N., Phiri, M., Akinyemi, A. I., Kim, R., Cheng, F., Song, Y., Lu, C., Subramanian, S., Geldsetzer, P., Qiu, Y., & Li, Z. (2025). Prevalence, disparities, and trends in intimate partner violence against women living in urban slums in 34 low-income and middle-income countries: A multi-country cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine, 81, 103140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherrier, C., Courtois, R., Rusch, E., & Potard, C. (2023). Self-Esteem, social problem solving and intimate partner violence victimization in emerging adulthood. Behavioral Sciences, 13(4), 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, A. M., González-Guarda, R. M., & Sandoval, M. T. (2013). Intimate partner violence among hispanics: A review of the literature. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doubova, S. V., Pámanes-González, V., Billings, D. L., & Del Pilar Torres-Arreola, L. (2007). Violencia de pareja en mujeres embarazadas en la Ciudad de México. Revista De Saúde Pública, 41(4), 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, C., Hegarty, K., D’Oliveira, A. F. P. L., Koziol-McLain, J., Colombini, M., & Feder, G. (2015). The health-systems response to violence against women. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliam, H. C., Martinez-Torteya, C., Carney, J. R., Miller-Graff, L. E., & Howell, K. H. (2024). “My Cross to Bear”: Mothering in the context of intimate partner violence among Pregnant women in Mexico. Violence Against Women, 10778012241289433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Guarda, R. M., Ortega, J., Vasquez, E. P., & De Santis, J. (2009). La Mancha Negra: Substance abuse, violence, and sexual risks among Hispanic males. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 32(1), 128–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Guarda, R. M., Vasquez, E. P., Urrutia, M. T., Villarruel, A. M., & Peragallo, N. (2010). Hispanic women’s experiences with substance abuse, intimate partner violence, and risk for HIV. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 22(1), 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, L., Bhowmik, J., Apputhurai, P., & Nedeljkovic, M. (2023). Factors and consequences associated with intimate partner violence against women in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 18(11), e0293295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INEGI. (2021). Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/tablerosestadisticos/vcmm/#General (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Mathews, S., Jewkes, R., & Abrahams, N. (2014). ‘So now I’m the Man’:Intimate partner femicide and its interconnections with expressions of masculinities in South Africa. The British Journal of Criminology, 55(1), 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina-Nuñez, I., & Medina-Villegas, A. (2019). Violencias contra las mujeres en las relaciones de pareja en México. Intersticios Sociales, 18, 269–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, S. M., Colombini, M., Lentz, E. C., Soriano, C. D., Morales, A. J. M., Olavarrieta, C. D., & Rodríguez, D. C. (2025). Political commitment and implementation: The health system response to violence against women in Mexico. Health Policy and Planning, 40(5), 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIG (Observatorio de Igualdad de Género). (2023). Available online: https://oig.cepal.org/es/indicadores/feminicidio (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Pahn, J., & Yang, Y. (2021). Behavioral problems in the children of women who are victims of intimate partner violence. Public Health Nursing, 38(6), 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M., Larkin, M., De Visser, R., & Fadden, G. (2010). Developing an interpretative phenomenological approach to focus group data. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 7(2), 99–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, M., Romo, L., Rogue, S., & Fouques, D. (2025). Intimate Partner Sexual Violence: A phenomenological Interpretative analysis among female survivors in France. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 40(1–2), 338–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummak, E., Demirtaş, E. T., & Özkan, H. (2025). Unheard voices of LGB people in Türkiye on LGB-specific experiences of intimate partner violence: A qualitative analysis. Violence Against Women, 31(8), 1727–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Universidad de las Américas. (2022). Global impunity dimensions. Universidad de las Américas Puebla-UDLAP. Available online: https://www.udlap.mx/cesij/files/indices-globales/IGI-MEX-2022-UDLAP.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- UNODC. (2019). Global study on homicide. Gender-related killing of women and girls. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/GSH2018/GSH18_Gender-related_killing_of_women_and_girls.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Valdez-Santiago, R., Híjar, M., Martínez, R. R., Burgos, L. Á., & De La Luz Arenas Monreal, M. (2013). Prevalence and severity of intimate partner violence in women living in eight indigenous regions of Mexico. Social Science & Medicine, 82, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Santiago, R., Juárez-Ramírez, C., Salgado de Snyder, V. N., Agoff, C., Ávila-Burgos, L., & Híjar, M. C. (2006). Violencia de género y otros factores asociados a la salud emocional de las usuarias del sector salud en México. Salud Publica Mex, 48(Suppl. S2), S250–S258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization). (2013). Global and regional estimates of violence against women: Prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, K., Giesbrecht, C. J., Brooks, C., & Arisman, K. (2024). “I Couldn’t Leave the Farm”: Rural women’s experiences of intimate partner violence and coercive control. Violence Against Women, 10778012241279117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Descriptive Data (n = 32) |

|---|---|

| Age, median (range) | 35 (24–70) |

| Civil status, n (%) | |

| - Single | 10 (31.2) |

| - Married, separated | 8 (25.0) |

| - Married, not separated | 8 (25.0) |

| - Free union | 3 (9.4) |

| - Divorced | 3 (9.4) |

| - Widow | 0 (0.0) |

| With romantic partner, n (%) | 11 (34.4) |

| With children, n (%) | 31 (96.9) |

| With job, n (%) | 13 (40.6) |

| With economic independence, n (%) | 15 (46.9) |

| Schooling, n (%) | |

| - Elementary school | 3 (9.4) |

| - High school | 11 (34.4) |

| - Preparatory | 10 (31.3) |

| - Bachelor’s degree | 7 (21.9) |

| - Master’s degree | 1 (3.0) |

| - Doctor in Philosophy (Ph.D.) | 0 (0.0) |

| Age of union with the aggressor (years), median (range) | 20 (13–29) |

| Age at which they started to experience violence, median (range) | 21.5 (13–30) |

| Time of separation from the aggressor (years), median (range) | 0.5 (0–22) |

| Perceptions of Causes of IPV | Perceptions of Consequences of IPV | Perceptions of Solutions to IPV |

|---|---|---|

Cultural causes:

| Psychological consequences:

| Prevention through education:

|

Emotional causes:

| Physical consequences:

| Psychological support:

|

Educative causes:

| Social consequences:

| Institutional strengthening:

|

Socioeconomic causes:

| Economic consequences:

| Women’s empowerment:

|

Family-related causes:

| Family-related consequences:

| Cultural transformation:

|

Addictions and substance abuse:

| Legal consequences:

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brambila-Tapia, A.J.L.; Brambila-Tostado, I.; Ortega-Medellín, M.P.; Ramírez-Cerón, G.G. Perceptions of Causes, Consequences, and Solutions of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Mexican Women Survivors of IPV: A Qualitative Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060723

Brambila-Tapia AJL, Brambila-Tostado I, Ortega-Medellín MP, Ramírez-Cerón GG. Perceptions of Causes, Consequences, and Solutions of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Mexican Women Survivors of IPV: A Qualitative Study. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):723. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060723

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrambila-Tapia, Aniel Jessica Leticia, Ignacio Brambila-Tostado, Martha Patricia Ortega-Medellín, and Giovanna Georgina Ramírez-Cerón. 2025. "Perceptions of Causes, Consequences, and Solutions of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Mexican Women Survivors of IPV: A Qualitative Study" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060723

APA StyleBrambila-Tapia, A. J. L., Brambila-Tostado, I., Ortega-Medellín, M. P., & Ramírez-Cerón, G. G. (2025). Perceptions of Causes, Consequences, and Solutions of Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Mexican Women Survivors of IPV: A Qualitative Study. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060723