Socioecological Models of Acculturation: The Relative Roles of Social and Contextual Factors on Acculturation Across Life Domains

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Models of Acculturation

1.2. A Socioecological Model of Acculturation

1.3. Current Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context

2.2. Participants and Participant Recruitment

2.3. Procedures and Instruments

2.3.1. Acculturation

2.3.2. Psychological Sense of Community (PSOC)

2.3.3. Intergroup Anxiety

2.3.4. Perceived Acculturation Preferences

2.3.5. Prejudice

2.3.6. Quality of Contact

2.3.7. Symbolic Threat

2.3.8. Demographic Measures

2.4. Analyses

3. Results

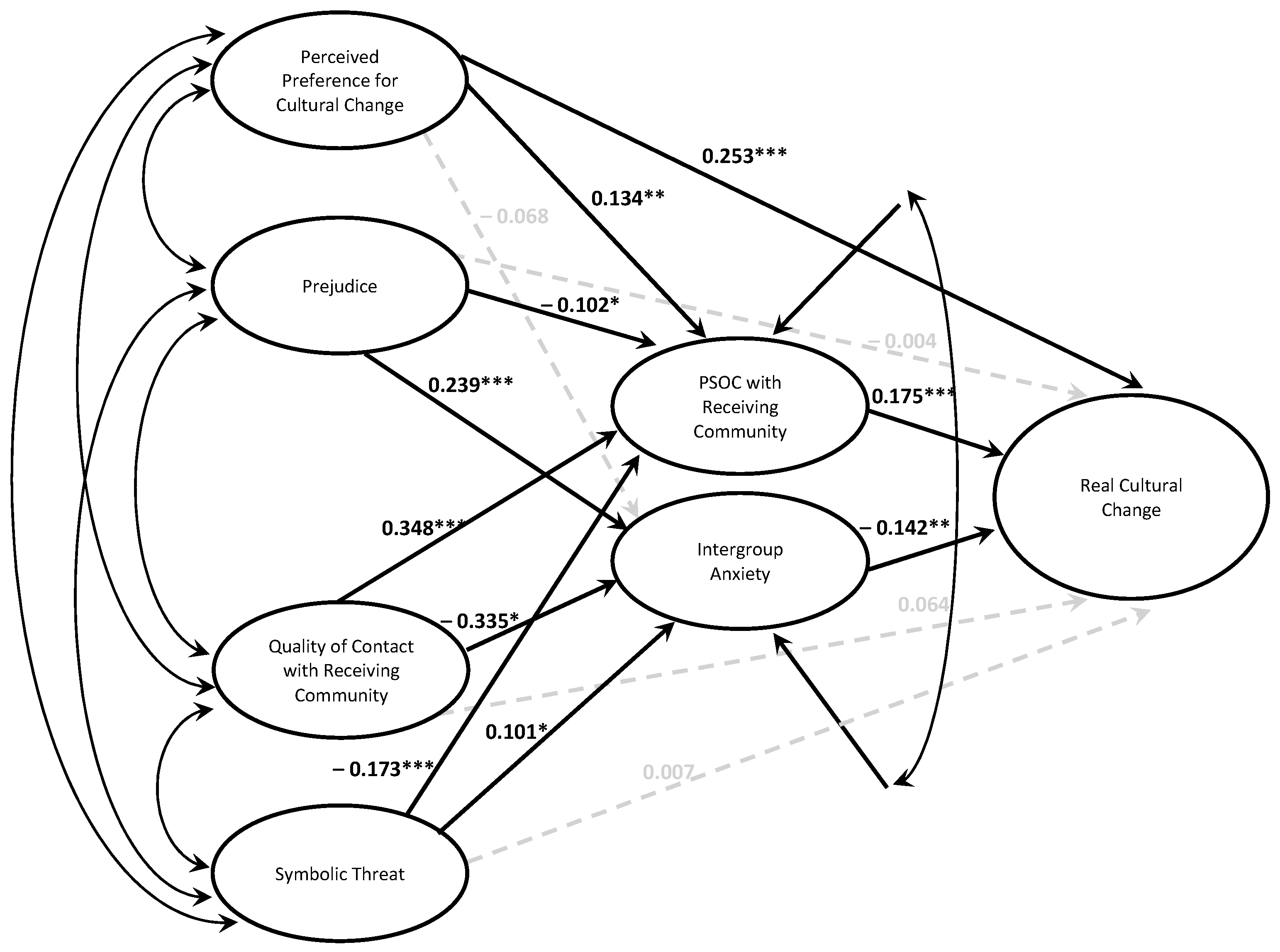

3.1. Main Path Models

3.2. Domain Models

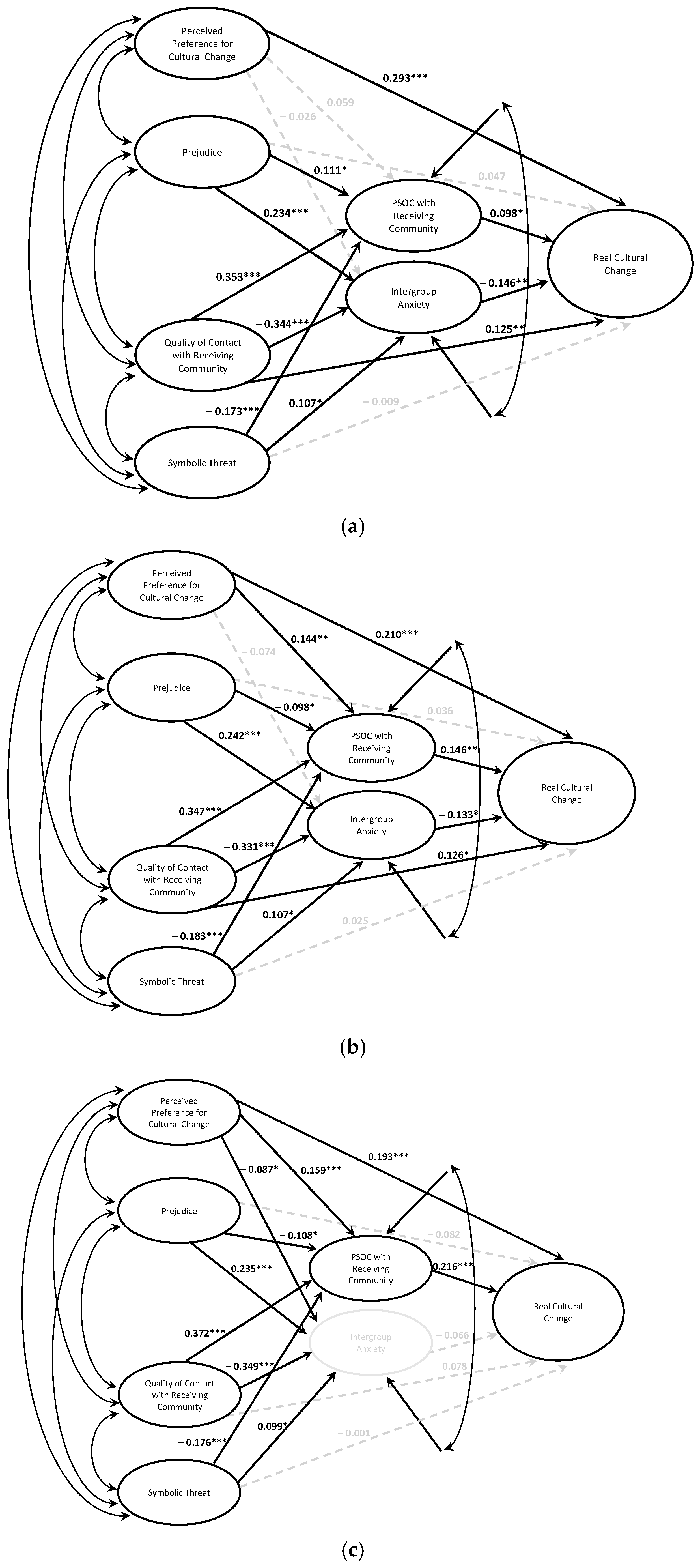

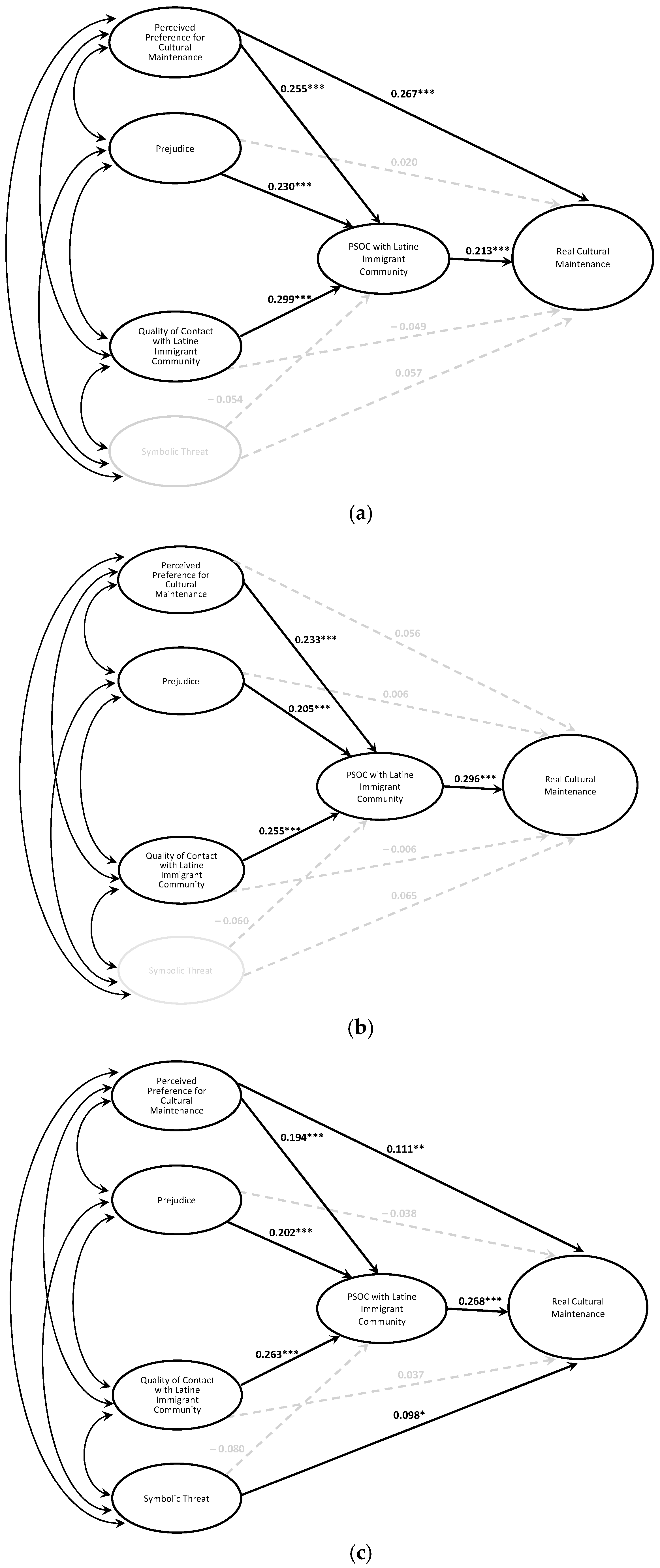

3.2.1. Peripheral

3.2.2. Intermediate

3.2.3. Central

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Future Directions

4.2. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PSOC | Psychological sense of community |

| RAEM | Relative acculturation extended model |

| US | United States |

| 1 | Immigration status was treated as a 3-point ordinal variable where 0 = no authorization, 1 = legal status, and 2 = naturalized citizenship. |

| 2 | No demographic variables were included as none were significantly correlated with the outcome of interest. |

| 3 | Immigration status and time in the U.S. were controlled for in the domain-level cultural change models; Domain models and test statistic tables are not included due to space constraints. They are available upon request. |

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, Y. (1969). Contact hypothesis in ethnic relations. Psychological Bulletin, 71, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arends-Tóth, J., van de Vijver, F. J., & Poortinga, Y. H. (2006). The influence of method factors on the relation between attitudes and self-reported behaviors in the assessment of acculturation. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 22(1), 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmania, A. (2015). Practically a community: Dynamics of a small city’s immigrant community. Undercurrent, 11, 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Bathum, M., & Baumann, L. (2007). A sense of community among immigrant Latinas. Family & Community Health, 30, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In A. M. Padilla (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models and some new findings (pp. 9–25). Westview. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. W. (2019). Acculturation: A personal journey across cultures. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, J. W., & Sam, D. L. (Eds.). (2006). The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, J., Zagefka, H., Brown, R., Funke, F., Kessler, T., Mummendey, A., Maquil, A., Demoulin, S., & Leyens, J. (2009). Does contact reduce prejudice or does prejudice reduce contact? A longitudinal test of the contact hypothesis among majority and minority groups in three European countries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96, 843–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birman, D., Trickett, E., & Buchanan, R. M. (2005). A tale of two cities: Replication of a study on the acculturation and adaptation of immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union in a different community context. American Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birtel, M. D., & Crisp, R. J. (2015). Psychotherapy and social change: Utilizing principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy to help develop new prejudice-reduction interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1771–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemraad, I. (2006). Becoming a citizen in the United States and Canada: Structured mobilization and immigrant political incorporation. Social Forces, 85(2), 667–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M. H. (2017). The specificity principle in acculturation science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 3–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, R. Y., Moise, L. C., Perreault, S., & Senecal, S. (1997). Towards an interactive acculturation model: A social psychological approach. International Journal of Psychology, 32, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Harvey, R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(1), 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodsky, A. E., Loomis, C., & Marx, C. M. (2002). Expanding the conceptualization of PSOC. In A. T. Fisher, C. C. Sonn, B. J. Bishop, A. T. Fisher, C. C. Sonn, & B. J. Bishop (Eds.), Psychological sense of community: Research, applications, and implications (pp. 319–336). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham, S. L., & Brodsky, A. E. (2015). “Our differences don’t separate us”: Immigrant families navigate intrafamilial acculturation gaps through diverse resilience processes. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 3(3), 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, S. L., Brodsky, A. E., Rochira, A., Fedi, A., Mannarini, T., Emery, L., Godsay, S., Miglietta, A., & Gattino, S. (2018a). Shared communities: A multinational qualitative study of immigrant and receiving community members. American Journal of Community Psychology, 62(1–2), 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, S. L., Emery, L., Godsay, S., Brodsky, A. E., & Scheibler, J. E. (2018b). ‘You opened my mind’: Latinx immigrant and receiving community interactional dynamics in the United States. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(2), 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, S. L., & Suarez-Pedraza, M. C. (2019). “It has cost me a lot to adapt to here”: The divergence of real acculturation from ideal acculturation impacts Latinx immigrants’ psychosocial wellbeing. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(4), 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, F. L., Colombo, M., Maffeis, D., & Montali, L. (2011). Sense of community and interethnic relations: Comparing local communities varying in ethnic heterogeneity. Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 663–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavis, D. M., Lee, K. S., & Acosta, J. D. (2008, June 4–6). The sense of community (SCI) revised: The reliability and validity of the SCI-2. 2nd International Community Psychology Conference, Lisboa, Portugal. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, S. Y., & Phillimore, J. (2014). Refugees, social capital, and labour market integration in the UK. Sociology, 48(3), 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirkov, V. (2009). Critical psychology of acculturation: What do we study and how do we study it, when we investigate acculturation? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Proctor, S. M. (1999). Perceived racism scale for Latina/os [Database record]. APA Psyctests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandy, J., & Pe-Pua, R. (2013). Beyond mutual acculturation: Intergroup relations among immigrants, Anglo-Australians, and indigenous Australians. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie, 221, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessel, A., & Rogge, M. E. (2008). Evaluation of intergroup dialogue: A review of the empirical literature. Conflict Resolution Quarterly, 26(2), 199–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J., Durrheim, K., & Tredoux, C. (2005). Beyond the optimal contact strategy: A reality check for the contact hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60(7), 697–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, M., & Almgren, G. (2009). Local contexts of immigrant and second-generation integration in the united states. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35(7), 1059–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedi, A., Mannarini, T., Brodsky, A. E., Rochira, A., Buckingham, S. L., Emery, L. R., Godsay, S., Scheibler, J. E., Miglietta, A., & Gattino, S. (2019). Acculturation in the discourse of immigrants and receiving community members. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 89(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golash-Boza, T., & Valdez, Z. (2018). Nested contexts of reception: Undocumented students at the University of California, Central. Sociological Perspectives, 61(4), 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J. R. (2006). Promoting Hmong refugees’ well-being through mutual learning: Valuing knowledge, culture, and experience. American Journal of Community Psychology, 37, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodkind, J. R., & Hess, J. M. (2017). Refugee well-being project: A model for creating and maintaining communities of refuge in the United States. In D. Haines, J. Howell, & F. Keles (Eds.), Maintaining refuge: Anthropological reflections in uncertain times (pp. 139–146). American Anthropological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind, J. R., Hess, J. M., Vasquez Guzman, C. E., & Hernandez-Vallant, A. (2024). From multilevel to trans-level interventions: A critical next step for creating sustainable social change to improve mental health. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurin, P., Nagda, B. A., & Zúñiga, X. (2013). Dialogue across difference: Practice, theory, and research on intergroup dialogue. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Horenczyk, G., Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2015). Mutuality in acculturation. Zeitschrift für Psychologie. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., & Liu, C. Y. (2018). Welcoming cities: Immigration policy at the local government level. Urban Affairs Review, 54(1), 3–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinskaja-Lahti, I., Liebkind, K., & Solheim, E. (2009). To identify or not to identify? National disidentification as an alternative reaction to perceived ethnic discrimination. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 58(1), 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonner, W. J. (1994). Culture and human diversity. In E. J. Trickett, R. J. Watts, & D. Birman (Eds.), Human diversity: Perspectives on people in context (pp. 230–243). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Malsbary, C. B. (2014). “It’s not just learning English, it’s learning other cultures”: Belonging, power, and possibility in an immigrant contact zone. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27, 1312–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannarini, T., Talò, C., Mezzi, M., & Procentese, F. (2018). Multiple senses of community and acculturation strategies among migrants. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1), 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, C., McClure, H., Eddy, J., Ruth, B., & Hyers, M. (2012). Recruitment and retention of Latino immigrant families in prevention research. Prevention Science, 13, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsudaira, T. (2006). Measures of psychological acculturation: A review. Transcultural Psychiatry, 43(3), 462–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maya-Jariego, I. (2006). Webs of compatriots: Relationship networks among immigrants. In J. L. Pérez Pont (Ed.), Geografías del desorden: Migración, alteridad y nueva esfera social (pp. 257–276). Universidad de Valencia. [Google Scholar]

- Maya-Jariego, I., & Armitage, N. (2007). Multiple senses of community in migration and commuting: The interplay between time, space and relations. International Sociology, 22, 743–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbise, A., Buckingham, S., Chen, T. C., Kuhn, S., Gat, N., & Kimmel, M. (2022). Welcoming cities: Skilled immigrant integration and inclusion in a United States city. In R. Baikady, S. Sajid, V. Nadesan, J. Przeperski, M. R. Islam, & J. Gao (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of global social change (pp. 1–17). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moftizadeh, N., Zagefka, H., & Barn, R. (2021). Majority group perceptions of minority acculturation preferences: The role of perceived threat. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 84, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, B., & Risco, C. (2006). Perceived discrimination experiences and mental health of Latina/o American persons. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, M. S., García, M. C., Sánchez, J., Rojas, A. J., Pumares, P., & Fernández, J. S. (2005). Relative acculturation extended model (RAEM): New contributions with regard to the study of acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas, M. S., Rojas, A. J., García, M., & Pumares, P. (2007). Acculturation strategies and attitudes according to the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM): The perspectives of natives versus immigrants. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31(1), 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obst, P. M., & White, K. M. (2005). An exploration of the interplay between psychological sense of community, social identification and salience. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 15, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, N. (2021). Nested contexts of reception: Latinx identity development across a new immigrant community. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 44(11), 1995–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2024). Immigrant America: A portrait. Univ of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, R., Linton, R., & Herskovits, M. J. (1936). Memorandum for the study of acculturation. American Anthropologist, 38, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudmin, F. W. (2003). Critical history of the acculturation psychology of assimilation, separation, integration, and marginalization. Review of General Psychology, 7, 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Lorenzo-Blanco, E. I., Des Rosiers, S. E., Villamar, J. A., Soto, D. W., Pattarroyo, M., Baezconde-Garbanati, L., & Szapocznik, J. (2014). Perceived context of reception among recent Hispanic immigrants: Conceptualization, instrument development, and preliminary validation. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., & Szapocznik, J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonn, C. C. (2002). Immigrant adaptation: Understanding the process through sense of community. In A. T. Fisher, C. C. Sonn, B. J. Bishop, A. T. Fisher, C. C. Sonn, & B. J. Bishop (Eds.), Psychological sense of community: Research, applications, and implications (pp. 205–222). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, W. G. (2014). Intergroup anxiety: Theory, research, and practice. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 18, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W. G., & Stephan, C. W. (2000). An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination (pp. 23–45). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, W. G., Boniecki, K. A., Ybarra, O., Bettencourt, A., Ervin, K. S., Jackson, L. A., McNatt, P. S., & Renfro, C. L. (2002a). Intergroup anxiety scale–modified [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, W. G., Boniecki, K. A., Ybarra, O., Bettencourt, A., Ervin, K. S., Jackson, L. A., McNatt, P. S., & Renfro, C. L. (2002b). Symbolic threats measure [Database record]. APA PsycTests. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolle, D., & Harell, A. (2013). Social capital and ethno-racial diversity: Learning to trust in an immigrant society. Political Studies, 61(1), 42–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townley, G., Kloos, B., Green, E. P., & Franco, M. M. (2011). Reconcilable differences? Human diversity, cultural relativity, and sense of community. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, R. N., Hewstone, M., Voci, A., & Vonofakou, C. (2008). A test of the extended intergroup contact hypothesis: The mediating role of intergroup anxiety, perceived ingroup and outgroup norms, and inclusion of the outgroup in the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 843–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdez, C. R., Lewis Valentine, J., & Padilla, B. (2013). ‘Why we stay’: Immigrants’ motivations for remaining in communities impacted by anti-immigration policy. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzali, L., & Giovannini, D. (2010). Social dominance orientation, realistic and symbolic threat: Effects on Italians’ acculturation orientations, intergroup attitudes and emotions toward immigrants. TPM-Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 17(3), 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Walia, H. (2021). Border and rule: Global migration, capitalism, and the rise of racist nationalism. Haymarket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Welcoming America. (2016). The welcoming standard & certified welcoming. Available online: https://welcomingamerica.org/the-welcoming-standard/ (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Yakushko, O. (2009). Xenophobia: Understanding the roots and consequences of negative attitudes toward immigrants. Counseling Psychologist, 37, 36–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| M | SD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.91 | 12.93 | |

| Years in the United States | 16.56 | 9.50 | |

| Proportion of Life in U.S. | 44.8% | 22.4% | |

| Region of Origin | |||

| Mexico | 52.0% | ||

| Central America | 25.0% | ||

| South America | 19.8% | ||

| Caribbean Islands | 3.2% | ||

| Gender | |||

| Woman | 60.6% | ||

| Man | 38.2% | ||

| Other | 1.2% | ||

| Level of Education | |||

| None–8th grade | 20.5% | ||

| 9th grade–Diploma/GED | 32.5% | ||

| Some College–Bachelor’s | 37.5% | ||

| Postgraduate Degree | 9.5% | ||

| Employment Status | |||

| Employed | 66.5% | ||

| Unemployed | 7.8% | ||

| Other (Homemaker, Student, Retired, Disabled) | 25.7% | ||

| Immigration Status | |||

| U.S. Citizenship | 39.2% | ||

| Permit | 29.9% | ||

| No Authorization or No Answer | 30.9% | ||

| Variable | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ideal Cultural Change | 10.33 | 2.38 | |

| Peripheral | 3.55 | 0.87 | |

| Intermediate | 3.56 | 1.11 | |

| Central | 3.23 | 1.00 | |

| Real Cultural Change | 9.97 | 2.51 | |

| Peripheral | 3.49 | 0.89 | |

| Intermediate | 3.35 | 1.11 | |

| Central | 3.14 | 1.00 | |

| Ideal Cultural Maintenance | 11.14 | 2.23 | |

| Peripheral | 3.19 | 0.90 | |

| Intermediate | 3.82 | 1.04 | |

| Central | 4.13 | 0.86 | |

| Real Cultural Maintenance | 9.98 | 2.35 | |

| Peripheral | 2.83 | 0.91 | |

| Intermediate | 3.39 | 1.07 | |

| Central | 3.75 | 0.93 | |

| Perceived Cultural Change Preferences of Receiving Community | 10.43 | 2.79 | |

| Peripheral | 3.69 | 1.00 | |

| Intermediate | 3.42 | 1.16 | |

| Central | 3.32 | 1.04 | |

| Perceived Cultural Maintenance Preferences of Receiving Community | 8.14 | 2.73 | |

| Peripheral | 2.51 | 0.98 | |

| Intermediate | 2.72 | 1.09 | |

| Central | 2.91 | 1.05 | |

| PSOC with Receiving Community | 57.63 | 15.65 | |

| PSOC with Latine Immigrant Community | 60.49 | 14.59 | |

| Intergroup Anxiety | 52.71 | 20.54 | |

| Prejudice | 17.51 | 12.21 | |

| Quality of Contact with U.S.-born People | 14.25 | 3.21 | |

| Quality of Contact with Latine Immigrants | 15.85 | 2.95 | |

| Symbolic Threat | 59.10 | 14.46 | |

| PSOC Receiving Comm. | Intergroup Anxiety | Real Cultural Change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t (p) | Partial r | t (p) | Partial r | t (p) | Partial r | |

| Step 1 | ||||||

| Immigration Status | 4.75 (p < 0.001) | 0.23 | −3.88 (p < 0.001) | −0.19 | 6.95 (p < 0.001) | 0.33 |

| Time in the U.S. | 1.88 (p = 0.062) | 0.09 | −2.63 (p = 0.009) | −0.13 | 2.15 (p = 0.032) | 0.11 |

| Ideal Cultural Change | 6.11 (p < 0.001) | 0.29 | −4.23 (p < 0.001) | −0.21 | 9.40 (p < 0.001) | 0.42 |

| Step 2 a | ||||||

| Perceived Preference for Cultural Change | 2.94 (p = 0.003) | 0.15 | −1.55 (p = 0.121) | −0.08 | 6.04 (p < 0.001) | 0.29 |

| Prejudice | −2.18 (p = 0.030) | 0.11 | 5.28 (p < 0.001) | 0.26 | −0.08 (p = 0.504) | −0.00 |

| Quality of Contact with Receiving Community | 7.52 (p < 0.001) | 0.35 | −7.50 (p < 0.001) | −0.35 | 1.37 (p = 0.170) | 0.07 |

| Symbolic Threat | −3.84 (p < 0.001) | −0.19 | 2.31 (p = 0.021) | 0.12 | 0.16 (p = 0.872) | 0.01 |

| PSOC with Receiving Community | — | — | — | — | 3.68 (p < 0.001) | 0.18 |

| Intergroup Anxiety | — | — | — | — | −2.87 (p = 0.004) | −0.14 |

| Through PSOC: Receiving Comm. | Through Intergroup Anxiety | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t | p | t | p | |

| Perceived Preferred Cultural Change | 2.24 | 0.013 | −1.32 | 0.093 |

| Prejudice | −1.81 | 0.035 | −2.56 | 0.005 |

| Quality of Contact with Receiving Community | 3.26 | <0.001 | 2.75 | 0.003 |

| Symbolic Threat | −2.59 | 0.005 | −1.76 | 0.039 |

| PSOC Receiving Comm. | Real Cultural Maintenance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t (p) | Partial r | t (p) | Partial r | |

| Step 1 | ||||

| Ideal Cultural Maintenance | 6.32 (p < 0.001) | 0.30 | 12.59 (p < 0.001) | 0.53 |

| Step 2 a | ||||

| Perceived Preference for Cultural Maintenance | 5.50 (p < 0.001) | 0.15 | 3.40 (p < 0.001) | 0.17 |

| Prejudice | 4.48 (p < 0.001) | 0.11 | −0.21 (p = 0.832) | −0.01 |

| Quality of Contact with Latine Immigrants | 5.59 (p < 0.001) | 0.35 | −0.40 (p = 0.693) | −0.02 |

| Symbolic Threat | −1.45 (p = 0.149) | −0.19 | 2.08 (p = 0.039) | 0.10 |

| PSOC with Latine Immigrant Community | — | — | 7.56 (p < 0.001) | 0.35 |

| Through PSOC: Immigrant Comm. | ||

|---|---|---|

| t | p | |

| Perceived Preferred Cultural Maintenance | 4.43 | <0.001 |

| Prejudice | 3.81 | <0.001 |

| Quality of Contact with Latine Immigrants | 4.47 | <0.001 |

| Symbolic Threat | −1.41 | 0.080 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buckingham, S.L. Socioecological Models of Acculturation: The Relative Roles of Social and Contextual Factors on Acculturation Across Life Domains. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060715

Buckingham SL. Socioecological Models of Acculturation: The Relative Roles of Social and Contextual Factors on Acculturation Across Life Domains. Behavioral Sciences. 2025; 15(6):715. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060715

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuckingham, Sara L. 2025. "Socioecological Models of Acculturation: The Relative Roles of Social and Contextual Factors on Acculturation Across Life Domains" Behavioral Sciences 15, no. 6: 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060715

APA StyleBuckingham, S. L. (2025). Socioecological Models of Acculturation: The Relative Roles of Social and Contextual Factors on Acculturation Across Life Domains. Behavioral Sciences, 15(6), 715. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs15060715